Abstract

Spinal cord injury leads to increased risk for cardiovascular disease and results in greater risk of death. Subclinical markers of atherosclerosis have been reported in carotid arteries of spinal cord-injured individuals (SCI), but the development of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease (PAD) has not been investigated in this population. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of spinal cord injury on ankle-brachial index (ABI) and intima-media thickness (IMT) of upper-body and lower-extremity arteries. We hypothesized that the aforementioned measures of lower-extremity PAD would be worsened in SCI compared with controls and that regular participation in endurance exercise would improve these in both groups. To test these hypotheses, ABI and IMT were determined in 105 SCI and compared with 156 able-bodied controls with groups further subdivided into physically active and sedentary. ABIs were significantly lower in SCI versus controls (0.96 ± 0.12 vs. 1.06 ± 0.07, P < 0.001), indicating a greater burden of lower-extremity PAD. Upper-body IMTs were similar for brachial and carotid arteries in controls versus SCI. Lower extremity IMTs revealed similar thicknesses for both superficial femoral and popliteal arteries, but when normalized for artery diameter, individuals with SCI had greater IMT than controls in the superficial femoral (0.094 ± 0.03 vs. 0.073 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter, P < 0.01) and popliteal (0.117 ± 0.04 vs. 0.091 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter, P < 0.01) arteries. The ABI and normalized IMT of SCI compared with controls indicate that subclinical measures of lower-extremity PAD are worsened in individuals with SCI. These findings should prompt physicians to consider using the ABI as a screening method to detect lower-extremity PAD in SCI.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, exercise

cardiovascular disease (CVD) contributes to more than 40% of deaths in spinal cord-injured individuals (SCI) (9). Interestingly, the mortality risk from CVD is 5–10% greater in SCI compared with age- and risk factor-matched able-bodied individuals (22). Specifically, it has been demonstrated that spinal cord injury leads to greater coronary artery calcification (24) and T-wave abnormalities (33), but evidence is equivocal regarding the development of subclinical atherosclerotic markers of carotid artery (CA) intima-media thickening and arterial stiffness (14, 18). The potential mechanisms for atherosclerosis in SCI include disorders of carbohydrate metabolism (1), dyslipidemia (1, 28), lower-extremity physical inactivity, and the resultant loss of lean body tissue (21), reduced daily energy expenditure (5), and greater prevalence of type 2 diabetes (2). Furthermore, especially in the lower extremities, altered hemodynamics reported post-spinal cord injury may place additional risk of arterial wall endothelial dysfunction leading to subclinical atherosclerosis (13, 35). Indeed, for SCI compared with able-bodied controls, reduced vascular function has been reported in the posterior tibialis of the legs but not in the radial artery of the arms, and this decline worsens with greater duration postinjury (31, 32). Others have reported that vascular function is not altered in the superficial femoral artery (SFA) of SCI, and, therefore, it remains unclear whether arterial function declines in other arteries of the lower extremities. (38) The reported CVD rates in SCI, however, may underestimate the prevalence of this disease because of the fact that the epidemiological and experimental studies describing the incidence of atherosclerotic CVD in SCI have focused on the coronary circulation. It is currently not known whether these risks may also contribute to a greater prevalence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in SCI. Evidence for increased PAD after spinal cord injury may also be derived from amputation data, indicating that the cause of tissue death was attributed to atherosclerotic plaques in 40% of amputation cases (11).

It is well known that exercise exerts its antiatherogenic effects through modifications of traditional risk factors, but other factors such as hemodynamics during exercise may also play a role (17, 19). Exercise has been shown to increase blood flow and shear rates by 20-fold or more in the legs during lower-body exercise (26), but the necessary threshold of these forces in creating antiatherosclerotic environments is not known. Interestingly, upper-body exercise has been shown to increase blood flow in the legs of both able-bodied and SCI but to less of an extent as possible for leg exercise (34, 37). In addition, upper-body exercise improves symptoms of PAD in able-bodied individuals, but it is unclear whether upper-body exercise may benefit the lower-extremity vasculatures of SCI. Therefore, the purpose of this investigation was to investigate the prevalence of PAD in SCI using the ankle-brachial index (ABI) and intima-media thickness (IMT), measured via ultrasonography. We hypothesized that the incidence of lower-body PAD as determined by ABI and IMT would be greater in SCI compared with able-bodied controls because of higher incidence of traditional CVD risk factors, reduced physical activity, and lower daily peak shear stress in the quiescent lower extremities of SCI. A second aim for this study was to determine whether chronic upper-body physical activity in SCI would reduce the prevalence of this disease compared with their sedentary counterparts. We hypothesized that physical activity would confer a benefit to the arteries in the legs of SCI.

METHODS

Subjects.

Studies were performed on 105 SCI and 156 controls. Subject characteristics are reported in Table 1. A medical history questionnaire including items regarding traditional cardiovascular risk factors was completed: this included asking subjects to report regular use of medications, cholesterol, smoking behavior, and history of hypertension. Medication usage is reported in Table 2. Furthermore, participants were asked questions about their physical activity habits including exercise type, minutes per day, days per week, and weeks per year: these questions were used to determine physical activity status and further subdivided the groups into active SCI (SCI-A, n = 55), sedentary SCI (SCI-S, n = 50), active controls (ABC-A, n = 71), and sedentary controls (ABC-S, n = 85). Active groups met or exceeded 150 min/wk of moderate-intensity exercise recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine/American Heart Association. (12) The spinal cord injury group consisted of individuals with paraplegia (n = 74) or tetraplegia (n = 31) who were at least 5 years postinjury. Only American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale grades A, B, or C were included in the study and thus limited to subjects who primarily used wheelchairs for mobility activities. SCI were recruited from the patient population, served by the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago and across the midwest and southern United States through recreation and sporting groups. Control subjects were tested from similar geographic areas. Before participation, each subject was verbally informed of potential risks and discomforts associated with the study and signed written, informed consent. The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards of Purdue University and Northwestern University.

Table 1.

Descriptive data by group for active controls, sedentary controls, active SCI, and sedentary SCI

| Active Controls | Sedentary Controls | Active SCI | Sedentary SCI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injury duration, yr | NA | NA | 20.0 ± 9.0 | 18.4 ± 8.8 | NA |

| Age, yr | 40.5 ± 12.7 | 42.6 ± 11.6 | 39.3 ± 11.7 | 42.0 ± 9.9 | 0.37 |

| Sex, %men | 90.1 ± 30.3 | 84.7 ± 33.6 | 87.3 ± 30.8 | 90.0 ± 39.3 | 0.72 |

| Height, cm | 179.7 ± 8.4 | 176.9 ± 10.3 | 176.7 ± 11.4 | 179.0 ± 7.8 | 0.20 |

| Weight, kg | 83.1 ± 17.1 | 88.5 ± 20.6 | 79.6 ± 14.3 | 80.2 ± 22.0 | 0.03 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.6 ± 3.4 | 28.1 ± 6.0 | 25.5 ± 5.3 | 25.3 ± 3.4 | <0.01 |

| Smoking, packs/day | 0.002 ± 0.02 | 0.121 ± 0.32 | 0.064 ± 0.19 | 0.167 ± 0.30 | <0.01 |

| Relatives with CVD | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.05 |

| Diabetes, % | 4.2 ± 18.6% | 8.2 ± 24.6% | 7.2 ± 30.7% | 12.0 ± 34.4 | 0.47 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 122 ± 11.5 | 125 ± 12.8 | 125 ± 15.4 | 129 ± 21.3 | 0.07 |

Values are means ± SD. SCI, spinal cord-injured individuals; NA, not applicable; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; Systolic BP, average systolic blood pressure for right and left brachial arteries.

Table 2.

Subject self-report of at least one medication used by general drug class

| Medication Category | Controls, % | SCI, % |

|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulants | 5.77 | 5.71 |

| Antihypertensives/antiarrhythmics | 9.62 | 11.43 |

| Antilipidemics | 13.46 | 4.76 |

| Insulin/glucophages | 3.21 | 3.81 |

| CNS-D/MR/anti-convulsants/sedatives | 5.77 | 43.81 |

| Antidepressants | 6.41 | 8.57 |

| NSAIDs/analgesics | 9.62 | 21.90 |

| Bladder | 5.13 | 28.57 |

| Urinary tract-related antibiotics | 0.00 | 9.52 |

| Laxatives/antiperistaltic agents | 0.00 | 16.19 |

| Gastric reflux | 8.33 | 11.43 |

| Hormone replacement/birth control | 1.92 | 3.81 |

| Thyroid analogs | 2.56 | 0.95 |

| Other antibiotics and antiviral | 1.92 | 1.90 |

| Antipsoriatics | 1.28 | 0.00 |

| Erectile dysfunction | 0.00 | 13.33 |

CNS-D, central nervous system depressants; MR, muscle relaxants; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Experimental protocol.

An individual testing session was completed within the same day. On the day of the study, subjects reported to testing, completed a medical history, and answered questions about their physical activity habits after which they transferred to a padded examination table and rested supine for a minimum of 5 min. An ABI was performed for both sides of the body, followed by vascular imaging via ultrasound on the side with the lowest ABI. The same investigator performed all ABIs and ultrasonography.

Measurements.

The ABI is commonly used in clinical and research settings to diagnose and measure severity of lower extremity PAD. The ABI as a screening tool for PAD has been validated in a small spinal cord-injured population without overt CVD risk factors (10). To obtain an ABI, our subjects were fitted with a limb-appropriate blood pressure cuff (Hokanson SC10/SC12, Bellevue WA). A bidirectional Doppler probe (Hokanson MD6) was placed at a 60° angle to the artery of interest and used to detect systolic pressure during cuff deflation. Systolic pressures were determined in the brachial, anterior tibialis, and posterior tibialis arteries. The ABI was calculated as the ratio of systolic pressures in the ankles to the brachial artery (BA), using the higher ABI from the two tibialis arteries. The higher pressure method has been proposed to most accurately detect clinically relevant PAD in the general population (16).

The IMT of four arteries was measured via ultrasound (Terason T3000, Burlington MA), using a variable frequency transducer (5–12 MHz). The BA, CA, and SFA were measured with the subject supine, and the popliteal artery (PA) was measured with the subject lying prone. Each artery was measured in the longitudinal plane, using B-mode with a high-frequency setting (25). Specific anatomical landmarks were used at each site of measurement to ensure that the measurements were consistent between all subjects. The BA was imaged above the antecubital fossa, and the CA images were taken adjacent to the inferior border of the carotid bulb. In the leg, the SFA images were obtained in the subsartorial canal distal to the bifurcation of the common femoral artery, whereas the PA was measured in the popliteal fossa. A 10-s video file was recorded, and the IMT was continuously analyzed during the duration of the video along the most clearly visible region of interest that allowed automated edge-detection software (Medical Imaging Applications LLC Carotid Analyzer 5, Coralville, IA) to easily track the media-adventitia border and the intima-lumen border of the far wall. It is appropriate to compare IMT of differently sized arteries by normalizing per millimeter of internal diameter (23). Therefore, arterial diameter was determined using a low-frequency setting and automated detection software (Medical Imaging Applications LLC Brachial Analyzer 5), allowing the calculation of IMT normalized per millimeter of lumen diameter. IMT and artery diameter were determined to the nearest hundredth of a millimeter, and IMT normalized to artery diameter was calculated to the nearest thousandth of a millimeter per millimeter of artery lumen diameter. Two separate investigators analyzed all IMT and artery diameter measurements with an average IMT coefficient of variation of 6.68% for absolute IMT and 10.06% for normalized IMT across all four arteries measured.

Statistical analysis.

Statistics were performed using commercially available programs (SAS versions 9.1 and 9.2, Cary, NC). One-way ANOVA was used with covariates added to the model when indicated to determine group differences between SCI and controls. Covariates were tested for model significance only when they significantly differed between SCI and controls. To determine differences for chronic exercise, a two-level factor for activity was included. Least square means was used post hoc to determine within group differences. To investigate associations between variables, correlations were performed via Pearson product-moment correlation analysis. All data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical significance was established a priori as P < 0.05.

During analysis of reported traditional cardiovascular risk factors, covariates emerged that were included within each model. BA-IMT and BA-IMT normalized per millimeter of diameter included white racial identity in each model, whereas normalized BA-IMT also included body mass. CA-IMT included the factor of body mass, whereas CA-IMT normalized to artery diameter included black racial identity. Both absolute and normalized SFA-IMT models included the number of relatives reported to have CVD, and the absolute SFA-IMT model also included body mass index. The absolute PA-IMT indicated body mass to be a significant covariate, whereas normalized PA-IMT had no significant model covariates.

RESULTS

Group characteristics.

For SCI, the mean duration of injury was 19.3 ± 8.9 yr with a range of 5.0–41.2 yr. There were no significant differences between groups for age, sex, height, prevalence of diabetes, number of reported relatives with CVD, or average systolic brachial blood pressure (Table 1). When compared with controls, SCI exhibited greater tobacco smoking behavior, lower body weight, and lower body mass index (Table 1). For race, there were significant differences in percentage of Caucasian and African-American subjects by group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percent race distribution by group for active controls, sedentary controls, active SCI, and sedentary SCI

| Race | Active Controls | Sedentary Controls | Active SCI | Sedentary SCI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian, % | 80.3 ± 35.9 | 74.1 ± 41.9 | 70.9 ± 45.8 | 46.0 ± 50.3 | <0.01 |

| Hispanic, % | 7.0 ± 26.5 | 11.8 ± 32.4 | 14.5 ± 35.0 | 14.0 ± 35.6 | 0.54 |

| African-American, % | 14.1 ± 28.7 | 15.3 ± 32.4 | 12.7 ± 33.6 | 40.0 ± 49.5 | <0.01 |

| Asian, % | 4.2 ± 20.8 | 2.4 ± 15.2 | 3.6 ± 18.9 | 0.00 | 0.53 |

Values are means ± SD. Multiracial subjects were able to claim more than one racial identity.

Ankle-brachial index.

ABIs (Table 4) were larger in controls versus SCI (1.06 ± 0.07 vs. 0.96 ± 0.12, P < 0.001). Two control individuals and 29 SCI had ABIs measuring below the clinically accepted diagnostic threshold of 0.90. Additionally, ABI in 0 controls and 10 SCI were below 0.80. When the effects of physical activity in these groups were compared, an analysis revealed a significant interaction between group and physical activity level (P < 0.01) and a trend (P = 0.06) for physical activity in controls. Post hoc analysis indicated a trend for larger ABI in ABC-A compared with ABC-S (1.08 ± 0.07 vs. 1.05 ± 0.07, P = 0.06), whereas no differences were seen for physical activity in the SCI group ABI (0.94 ± 0.11 vs. 0.97 ± 0.10, P = 0.28). In SCI, ABI had a moderate negative correlation with number of years postinjury (r = 0.40, P < 0.01). This association remained after controlling for age (r = 0.39, P < 0.01).

Table 4.

Ankle-brachial index in controls versus SCI

| Group | Ankle-Brachial Index |

|---|---|

| All controls | 1.06 ± 0.07* |

| All SCI | 0.96 ± 0.12 |

| Active controls | 1.08 ± 0.07† |

| Sedentary controls | 1.05 ± 0.07† |

| Active SCI | 0.94 ± 0.11 |

| Sedentary SCI | 0.97 ± 0.10 |

Values are means ± SD.

P < 0.01, significant difference between control and SCI group;

P < 0.01, significant difference between control and active or sedentary SCI group values.

Intima-media thickness.

Upper-body artery IMT and diameter measurements are summarized in Table 5. BA-IMT was similar for control and SCI when expressed as absolute thickness (0.35 ± 0.07 vs. 0.36 ± 0.08 mm, P = 0.76). Interestingly, there was a significant beneficial effect of spinal cord injury in controls versus SCI for normalized BA-IMT (0.079 ± 0.02 vs. 0.077 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter, P = 0.02). BA diameter was smaller in control compared with SCI (4.47 ± 0.69 vs. 4.79 ± 0.88 mm, P < 0.01). In the BA, IMT was significantly correlated with diameter in control individuals (r = 0.33, P < 0.01). Absolute IMT measurements for CA were not significantly different in controls compared with SCI (0.61 ± 0.14 vs. 0.59 ± 0.15 mm, P = 0.60) or for normalized IMT (0.083 ± 0.02 vs. 0.081 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter, P = 0.37). Similarly, CA diameter measurements were not different for controls compared with SCI (7.34 ± 0.67 vs. 7.23 ± 0.65 mm, P = 0.19). There was, however, a significant effect of activity level with a smaller CA-IMT (0.57 ± 0.14 vs. 0.62 ± 0.14 mm, P < 0.02) and a smaller normalized CA-IMT (0.079 ± 0.02 vs. 0.085 ± 0.02, P < 0.05) in active subjects compared with sedentary subjects. When the activity level by group was compared, there were no significant differences for absolute or normalized CA-IMT. In the CA, IMT was significantly correlated with diameter in controls (r = 0.33, P < 0.01).

Table 5.

Arterial structure in upper-extremity arteries of controls and SCI

| Artery/Group | IMT, mm | IMT, per mm lumen | Diameter, mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brachial | |||

| All controls | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.079 ± 0.02 | 4.47 ± 0.69 |

| Active | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 0.078 ± 0.02 | 4.53 ± 0.69 |

| Sedentary | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.080 ± 0.02 | 4.42 ± 0.69§ |

| All SCI | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 0.077 ± 0.02* | 4.79 ± 0.88† |

| Active | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.074 ± 0.02 | 4.93 ± 0.91‡ |

| Sedentary | 0.36 ± 0.07 | 0.080 ± 0.02 | 4.64 ± 0.83 |

| Carotid | |||

| All controls | 0.61 ± 0.14 | 0.083 ± 0.02 | 7.34 ± 0.67 |

| Active | 0.58 ± 0.15 | 0.080 ± 0.02 | 7.30 ± 0.56 |

| Sedentary | 0.63 ± 0.15 | 0.085 ± 0.02 | 7.38 ± 0.75 |

| All SCI | 0.59 ± 0.15 | 0.081 ± 0.02 | 7.23 ± 0.65 |

| Active | 0.56 ± 0.10 | 0.078 ± 0.02 | 7.18 ± 0.56 |

| Sedentary | 0.62 ± 0.11 | 0.085 ± 0.02 | 7.28 ± 0.75 |

Values are means ± SD. IMT, intima-media thickness.

P < 0.05, significant difference between control and SCI group values;

P < 0.01, significant difference between control and SCI group values;

P < 0.05, significant difference between active SCI and active controls;

P < 0.01, significant difference between active SCI and sedentary controls.

SFA-IMT measurements are summarized in Table 6. SCI and control groups had similar absolute IMT measurements for the SFA (0.49 ± 0.12 vs. 0.50 ± 0.11 mm, P = 0.68), and when normalized to arterial lumen diameter, the SCI group IMT was significantly larger compared with controls (0.094 ± 0.03 vs. 0.073 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter, P < 0.01). Interestingly, the normalized SFA-IMT was not associated with number of years postinjury (r = −0.04, P = 0.67). The SFA diameters were smaller in SCI compared with controls (5.38 ± 0.94 vs. 6.89 ± 1.04 mm, P < 0.001). Additionally, SFA-IMT was significantly correlated with diameter of control subjects (r = 0.19, P = 0.02). When absolute IMT based on activity grouping was compared, the IMT in SFA of active compared with sedentary subjects was smaller (0.47 ± 0.11 vs. 0.51 ± 0.12 mm, P < 0.01). Post hoc analysis revealed that this effect was primarily located within the difference between SCI-A and SCI-S for SFA (0.46 ± 0.12 vs. 0.53 ± 0.17 mm, P < 0.02). Furthermore, these differences are amplified in the normalized IMT measurements of SFA-IMT with greater IMT in SCI compared with controls (0.094 ± 0.03 vs. 0.074 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter, P < 0.01). SCI-S had the largest normalized IMT (0.102 ± 0.04 mm/mm lumen diameter), followed by SCI-A (0.086 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter), ABC-S (0.077 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter), and smallest normalized IMT in ABC-A (0.069 ± 0.02). Differences were significant (P < 0.01) in ABC-A versus SCI-A, SCI-A versus SCI-S, ABC-S versus SCI-S, and ABC-A versus SCI-S. The larger normalized IMT in the ABC-S versus ABC-A was not significantly different (P = 0.07).

Table 6.

Arterial structure in lower-extremity arteries of controls and SCI

| Artery/Group | IMT, mm | IMT, per mm lumen | Diameter, mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial femoral | |||

| All controls | 0.50 ± 0.09 | 0.073 ± 0.02* | 6.89 ± 1.04* |

| Active | 0.49 ± 0.10 | 0.069 ± 0.02† | 7.11 ± 0.96† |

| Sedentary | 0.50 ± 0.08 | 0.077 ± 0.02‡ | 6.71 ± 1.07† |

| All SCI | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 0.094 ± 0.03 | 5.38 ± 0.94 |

| Active | 0.46 ± 0.13§ | 0.086 ± 0.02a | 5.37 ± 0.86 |

| Sedentary | 0.53 ± 0.18 | 0.102 ± 0.05 | 5.38 ± 1.02 |

| Popliteal | |||

| All controls | 0.60 ± 0.14 | 0.091 ± 0.02* | 6.71 ± 1.15* |

| Active | 0.58 ± 0.12 | 0.087 ± 0.02† | 6.79 ± 1.20† |

| Sedentary | 0.62 ± 0.15 | 0.094 ± 0.02† | 6.65 ± 1.11† |

| All SCI | 0.60 ± 0.18 | 0.117 ± 0.04 | 5.20 ± 0.91 |

| Active | 0.57 ± 0.18 | 0.116 ± 0.04 | 5.11 ± 0.96 |

| Sedentary | 0.62 ± 0.23 | 0.118 ± 0.04 | 5.30 ± 0.86 |

Values are means ± SD.

P < 0.01, significant difference between control and SCI group values;

P < 0.01, significant difference between control and both SCI activity group values;.

P < 0.01, significant difference between sedentary controls and sedentary SCI;

P < 0.05, significant difference between active SCI and sedentary SCI;

P < 0.01, significant difference between active SCI and sedentary SCI.

PA-IMT measurements are summarized in Table 6. Consistent with those of the SFA, PA absolute IMT measurements were similar between SCI and control groups (0.60 ± 0.18 vs. 0.60 ± 0.14 mm, P = 0.84). The diameters of the PA were smaller in SCI compared with controls (5.20 ± 0.91 vs. 6.71 ± 1.15 mm, P < 0.01). When arterial lumen diameter was normalized, the SCI group IMT was significantly larger compared with controls (0.117 ± 0.04 vs. 0.091 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter, P < 0.01). In SCI, there was a trend for greater normalized PA-IMT with longer injury duration (r = 0.16, P = 0.06). Additionally, there was no effect of physical activity for the absolute IMT of the PA. Similar to the SFA normalized IMT, the larger IMT in ABC-S compared with ABC-A was not significant (0.095 ± 0.02 vs. 0.087 ± 0.02 mm/mm lumen diameter, P = 0.44). ABC-A-normalized PA-IMT and ABC-S-normalized PA-IMT were smaller than in both SCI groups (P < 0.01), although both SCI groups were similar (P = 0.97). PA-IMT was significantly correlated with diameter for controls (r = 0.40, P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The elevated CVD risk factors and reduced physical activity of the legs in SCI suggest that the burden of PAD may be higher in these individuals compared with able-bodied controls. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine whether persons with spinal cord injury had worsened clinical measures for PAD when assessed by the ABI and IMT. Additionally, we sought to determine whether exercise would improve the occurrence of PAD as assessed by these measures. The primary new findings of this study are as follows: 1) the ABI is lower in SCI compared with controls, potentially indicating a greater prevalence of lower extremity PAD occurring in chronic SCI; 2) the normalized IMT of SFA and PA in SCI is larger than control populations, indicating the possibility for greater atherosclerotic disease; 3) able-bodied individuals who performed chronic physical activity had improvements in ABI, but these benefits of greater physical activity did not remain in the ABI of SCI groups; and 4) chronic exercise benefits the SFA-IMT in SCI but does not appear to protect the PA: this is in contrast to the improved PA-IMT in ABC-A. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document a greater subclinical prevalence of lower extremity PAD for SCI.

Spinal cord injury effects.

As previously stated, the ABI is a clinical measure for diagnosing lower-extremity PAD that has been validated in SCI. In the current investigation ABI was lower in SCI compared with ABC by 0.10. These results provide evidence for a greater burden of lower-extremity PAD in SCI than ambulatory populations. This is highlighted by the fact that 29 SCI, or 27.6% of SCI, in this study had ABI measurements below the clinically accepted threshold of 0.90, whereas only two control individuals, or 1.3%, met this threshold. However, others have suggested that using the higher pressure method for determining ABI that we used may underestimate the incidence of PAD compared with using the lower ankle systolic pressure for ABI calculation (20). Using the lower pressure from the two different tibialis arteries (ABI-L) method, we determined that the mean ABI-L was below (0.89 ± 0.13) the well-accepted clinical threshold of 0.90, and therefore this method may be valuable to clinicians wishing to screen their patients for PAD. Additionally, in active versus sedentary controls, we detected a significantly higher ABI-L (1.04 ± 0.07 vs. 0.99 ± 0.07, P = 0.02) but no differences in ABI-L in active or sedentary SCI (0.89 ± 0.13 vs. 0.90 ± 0.13, P = 0.90). To our knowledge, the only study to report ABI in SCI was performed in a small spinal cord-injured population (n = 15) that was free of overt CVD risk factors (10). To get a cross-sectional sampling of the spinal cord-injured population, our study did not exclude individuals on the basis of CVD risk profiles. Our higher pressure method yielded a mean ABI that was lower by 0.19 than that reported in SCI free of CVD risk factors. In the previously mentioned study, a negative association has been reported between ABI and greater number of years postinjury (10). Therefore, the greater average duration postinjury in the current study compared with the previous (19.3 ± 8.9 vs. 7.0 yr) may account for a portion of the lower ABI measurements in our SCI. This is consistent with our current finding that injury duration was correlated with reduced ABI in our SCI. It is possible with the clustering of risk factors occurring in SCI that these inclusion criteria could increase the likelihood of measuring a reduced ABI. This increased CVD risk would be the natural consequence of SCI in our population and therefore more accurately depict the prevalence of lower-extremity PAD.

As expected, the upper-body artery IMT measurements were not significantly different between groups. This is similar to results demonstrating no difference in CA-IMT between physically active SCI and age-matched controls. (14) Our absolute CA-IMT measurements for all SCI were slightly larger than those previously reported in 28 wheelchair athletes, ∼0.10 mm, but were 0.15 mm smaller than those reported for 34 SCI, including injuries causing paraplegia and tetraplegia (18). Interestingly, the normalized IMT in the BA was smaller in our SCI group. This small benefit may have appeared due to a larger BA diameter in this group, and the outward remodeling of this artery lumen is most likely a consequence of manual wheelchair usage and the repetitive activity of the arms in the majority of our subject population. Unfortunately, we did not collect data on manual versus power wheelchair use and cannot fully explore the differences seen in the BA. This activity-specific adaptation, however, is consistent with the report that the BA of the preferred arm in racquet sports players is significantly larger than the BA of the nonpreferred arm (27).

The lower extremity arteries were not different between groups when considering the absolute IMT. These IMTs are similar to previous reports of common femoral artery IMTs not differing between paraplegic, sedentary, and athletic individuals (29). As previously suggested, the paradox of these similar lower-extremity IMT measurement lies in the fact that arteries below the level of injury have a reduced diameter and therefore should have a reduced wall thickness in accordance with Laplace's Law (29). Herein lies a major tenant of this investigation in that artery diameter is related to the absolute IMT. In our able-bodied control individuals, correlations between artery diameter and IMT were significant. This suggests that diameter is responsible for a portion of the variance in the measurement and that other factors related to group conditions, such as greater atherosclerotic disease, explain most of the remaining variance. Indeed, in lower-extremity arteries, when normalized IMT are compared, SCI show greater thickening of the arterial intima-media. The artery diameter in the lower extremities is reduced to nearly half its original size within weeks of the injury (7). This suggests that a greater proportion of lumen is occupied by the IMT in SCI after the reductions in internal diameter occur. In our study, because of subject inclusion of at least 5 years postinjury, it is unclear whether the media fails to remodel to meet the reductions in internal diameter or whether thickening is occurring because of atherosclerotic processes in the intima. Although there was a trend in the PA, injury duration in our study was not significantly correlated to greater normalized IMT, and therefore these measurements should be investigated during the time of arterial remodeling immediately after the spinal cord injury has occurred to determine the role of remodeling on these measures. Regardless of the underlying causes, the normalized IMT in the lower extremity arteries of our SCI, particularly in the PA, mirrors the pattern of PAD determined by the ABI.

Exercise effects.

In control subjects who were chronic exercisers, both ABI methods yielded significantly higher indexes compared with those in sedentary controls. This pattern did not persist with the SCI. It is likely that exercise cannot ameliorate the causes of worsened ABI in the lower-extremity arteries of SCI. The effects of activity grouping were interesting when comparing the normalized IMT of the lower-body arteries. Similar to the ABI, the normalized PA-IMT had the best outcome in the ABC-A group, followed by the ABC-S. The normalized PA-IMT was not different when comparing active versus sedentary SCI. The current data do suggest that upper-body exercise is a strong enough stimulus for improved arterial structure in some arteries of SCI. In our SCI-A, both absolute and normalized SFA-IMT were smaller than sedentary SCI. These data suggest that the increased blood flow and shear reported during upper-body exercise (34, 36, 37) may confer some benefit in the SFA. The shear stimulus in the PA during upper-body wheelchair exercise is currently not known. It is possible that the distal location of this artery along with the position of this limb during physical activity may alter this hemodynamic pattern so that the benefit seen in SFA is not apparent in PA.

Limitations.

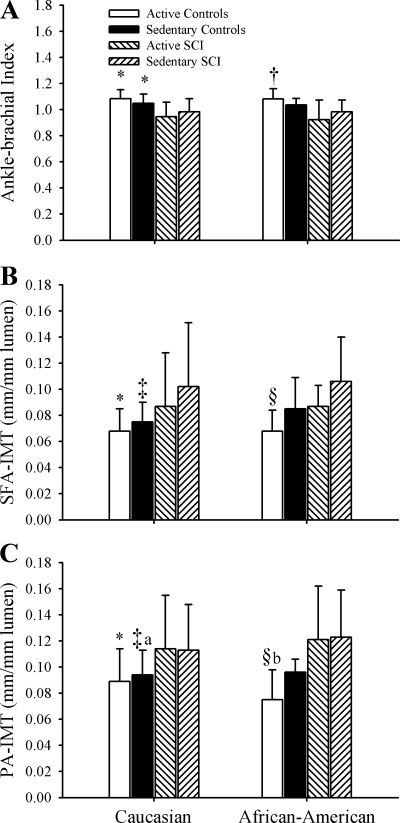

There are several limitations to this study that may limit our ability to generalize these results to all populations of SCI. Blood analysis for lipids was not performed in this study. We requested that blood lipids profiles obtained by the subject's physician within 12 months of the study date be reported, but subject participation was low (n = 41). We cannot rule out that differences in total, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride components, which have been reported to be altered in the spinal cord injury literature (1, 2, 28), may be driving the differences between our groups. However, we did not find differences between groups in CA-IMT measurements as would likely be the effect of elevated blood lipids circulating systemically. Additionally, subjects were categorized into active and sedentary groups based on self-reported minutes of endurance training activity. Although a parity of upper-body to lower-body exercise routines for atheroprotection is unlikely, recent reports for a wheelchair team sports participation has shown that individuals in these programs exercised at intensities that are within appropriate ranges for improving cardiorespiratory fitness (3). Furthermore, race differences existed between groups in our study. In particular, SCI-S was represented by a larger percentage of African-American individuals compared with the three other groups, including the SCI-S. Disability literature reflects greater rates of physical inactivity in mobility-limited minorities than able-bodied minorities, mobility-limited nonminorities, or able-bodied nonminorities (15). These differences, however, did not result in large differences in ABI or IMT between Caucasian and African-American individuals in this sample (Fig. 1, A–C). The lack of finding statistical differences in the African-American ABI and IMT measurements appears to be sample size related since patterns are quite similar. Additionally, greater smoking behavior was reported by our SCI with the greatest differences between active control and SCI groups. Greater smoking behavior has been reported in individuals with orthopedic disabilities (4) and American male veterans with spinal cord injuries ages 25 to 44 (30), but to our knowledge, there are no data that support the incidence of greater smoking behavior in physically active SCI compared with the general population. Also, with 50.4% of SCI in this study having injury levels above the splanchnic innervation, we cannot rule out the possibility that autonomic dysreflexia (AD), a reflexively activated large increase in systemic blood pressure, may have played a role in our results. AD is often triggered when SCI have pressure sores or experience other painful stimuli inferior to their injury level. Only 7.6% of our SCI reported current pressure sores with only one-third of those reporting pressure sores having injuries where they would be likely to experience AD. Therefore, we feel that it is unlikely that AD played a significant role in our results.

Fig. 1.

Ankle-brachial index (A), normalized superficial femoral artery intima-media thickness (SFA-IMT, mm/mm lumen diameter), and normalized popliteal artery IMT (PA-IMTC, mm/mm lumen diameter) in active able-bodied controls, sedentary able-bodied controls, active spinal cord-injured individuals (SCI), and sedentary SCI in Caucasian and African-American subjects. Data from least square means post hoc analysis are presented: *P < 0.01, control significantly different than active and sedentary SCI; †P < 0.05, active control significantly different than active SCI; ‡P < 0.01, sedentary control significantly different than sedentary SCI; §P < 0.01, active control significantly different than active SCI; aP < 0.05, sedentary control significantly different than active SCI; and bP < 0.05, active controls significantly different than active SCI. Error bars represent means ± SD.

Clinical relevance.

Greater rates of PAD are associated with an increased risk of future heart attack (4×) and stroke (3×) in able-bodied individuals (6). If these risk associations hold true for SCI, the elevated mortality rates in SCI (22) may partially be explained by the normalized IMT in their lower extremity arteries. Additionally, with many SCI being insensate in the lower extremities, typical symptoms for PAD are not detectable by the individual. Therefore, these data indicate that physicians who treat SCI should consider using the ABI for regular PAD screening in this population. The diagnosis and subsequent treatment of early stage, lower-extremity PAD would in turn have a direct positive impact on a spinal cord-injured individual's quality of life and health care costs associated with this disease. For instance, skin blood flow is reduced in the lower extremities of SCI and may be related to the development of pressure ulcerations (8). One can then speculate that PAD in the lower extremities of SCI may be related to the development of or increased healing time for skin breakdown lesions and that PAD identification may aid physicians in determining appropriate treatment.

Summary.

Results from this investigation suggest that elevated CVD risk for SCI includes a greater incidence of lower-extremity PAD. Measurements of ABI were worsened for persons with spinal cord injuries and were different for physically active SCI. This corresponds with a greater normalized IMT for SCI in the PA and SFA with evidence of improved normalized IMT in the SFA of active compared with sedentary SCI.

GRANTS

This project was funded, in part, with support from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, National Center for Research Resources Grant RR-025761, and a Clinical and Translational Sciences Award.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Bauman W, Kahn N, Grimm D, Spungen A. Risk factors for atherogenesis and cardiovascular autonomic function in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 37: 601–616, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bauman W, Spungen A. Disorders of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in veterans with paraplegia or quadriplegia: a model of premature aging. Metabolism 43: 749–756, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernardi M, Guerra E, Di Giacinto B, Di Cesare A, Castellano V, Bhambhani Y. Field evaluation of paralympic athletes in selected sports: implications for training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42: 1200–1208, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brawarsky P, Brooks D, Wilber N, Gertz RJ, Klein Walker D. Tobacco use among adults with disabilities in Massachusetts. Tob Control 11, Suppl 2: ii29–ii33, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buchholz A, McGillivray C, Pencharz P. Physical activity levels are low in free-living adults with chronic paraplegia. Obes Res 11: 563–570, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Criqui M, Langer R, Fronek A, Feigelson H, Klauber M, McCann T, Browner D. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med 326: 381–386, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Groot P, Bleeker M, van Kuppevelt D, van der Woude L, Hopman M. Rapid and extensive arterial adaptations after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 87: 688–696, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deitrick G, Charalel J, Bauman W, Tuckman J. Reduced arterial circulation to the legs in spinal cord injury as a cause of skin breakdown lesions. Angiology 58: 175–184, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garshick E, Kelley A, Cohen S, Garrison A, Tun C, Gagnon D, Brown R. A prospective assessment of mortality in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 43: 408–416, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grew M, Kirshblum S, Wood K, Millis S, Ma R. The ankle brachial index in chronic spinal cord injury: a pilot study. J Spinal Cord Med 23: 284–288, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grundy D, Silver J. Amputation for peripheral vascular disease in the paraplegic and tetraplegic. Paraplegia 21: 305–311, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, Macera CA, Heath GW, Thompson PD, Bauman A, American College of Sports Medicine; American Heart Association Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 116: 1081–1093, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hopman M, Nommensen E, van Asten W, Oeseburg B, Binkhorst R. Properties of the venous vascular system in the lower extremities of individuals with paraplegia. Paraplegia 32: 810–816, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jae SY, Heffernan KS, Lee M, Fernhall B. Arterial structure and function in physically active persons with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med 40: 535–538, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones G, Sinclair L. Multiple health disparities among minority adults with mobility limitations: san application of the ICF framework and codes. Disabil Rehabil 30: 901–915, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lange SF, Trampisch HJ, Pittrow D, Darius H, Mahn M, Allenberg JR, Tepohl G, Haberl RL, Diehm C; getABI Study Group Profound influence of different methods for determination of the ankle brachial index on the prevalence estimate of peripheral arterial disease. BMC Public Health 7: 147, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laughlin M, Roseguini B. Mechanisms for exercise training-induced increases in skeletal muscle blood flow capacity: differences with interval sprint training versus aerobic endurance training. J Physiol Pharmacol 59, Suppl 7: 71–88, 2008 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matos-Souza J, Pithon K, Ozahata T, Oliveira R, Téo F, Blotta M, Cliquet AJ, Nadruz WJ. Subclinical atherosclerosis is related to injury level but not to inflammatory parameters in spinal cord injury subjects. Spinal Cord 48: 740–744, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McAllister RM, Newcomer SC, Laughlin MH. Vascular nitric oxide: effects of exercise training in animals. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 33: 173–178, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McDermott M, Criqui M, Liu K, Guralnik J, Greenland P, Martin G, Pearce W. Lower ankle/brachial index, as calculated by averaging the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arterial pressures, and association with leg functioning in peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 32: 1164–1171, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McDonald C, Abresch-Meyer A, Nelson M, Widman L. Body mass index and body composition measures by dual x-ray absorptiometry in patients aged 10 to 21 years with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 30, Suppl 1: S97–S104, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Myers J, Lee M, Kiratli J. Cardiovascular disease in spinal cord injury: an overview of prevalence, risk, evaluation, and management. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 86: 142–152, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nishiyama S, Wray D, Richardson R. Aging affects vascular structure and function in a limb-specific manner. J Appl Physiol 105: 1661–1670, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orakzai S, Orakzai R, Ahmadi N, Agrawal N, Bauman W, Yee F, Adkins R, Waters R, Budoff M. Measurement of coronary artery calcification by electron beam computerized tomography in persons with chronic spinal cord injury: evidence for increased atherosclerotic burden. Spinal Cord 45: 775–779, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pignoli P, Tremoli E, Poli A, Oreste P, Paoletti R. Intimal plus medial thickness of the arterial wall: a direct measurement with ultrasound imaging. Circulation 74: 1399–1406, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Proctor D, Koch D, Newcomer S, Le K, Smithmyer S, Leuenberger U. Leg blood flow and V̇o2 during peak cycle exercise in younger and older women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36: 623–631, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rowley NJ, Dawson EA, Birk GK, Cable NT, George KP, Whyte G, Thijssen DH, Green DJ. Exercise and arterial adaptation in humans: uncoupling localized and systemic effects. J Appl Physiol 110: 1190–1195, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmid A, Halle M, Stutzle C, Konig D, Baumstark MW, Storch MJ, Schmidt-Trucksass A, Lehmann M, Berg A, Keul J. Lipoproteins and free plasma catecholamines in spinal cord injured men with different injury levels. Clin Physiol 20: 304–310, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schmidt-Trucksäss A, Schmid A, Brunner C, Scherer N, Zäch G, Keul J, Huonker M. Arterial properties of the carotid and femoral artery in endurance-trained and paraplegic subjects. J Appl Physiol 89: 1956–1963, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spungen A, Lesser M, Almenoff P, Bauman W. Prevalence of cigarette smoking in a group of male veterans with chronic spinal cord injury. Mil Med 160: 308–311, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stoner L, Sabatier M, VanhHiel L, Groves D, Ripley D, Palardy G, McCully K. Upper vs. lower extremity arterial function after spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 29: 138–146, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stoner L, Sabatier MJ, Mahoney ET, Dudley GA, McCully KK. Electrical stimulation-evoked resistance exercise therapy improves arterial health after chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 45: 49–56, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Szlachcic Y, Carrothers L, Adkins R, Waters R. Clinical significance of abnormal electrocardiographic findings in individuals aging with spinal injury and abnormal lipid profiles. J Spinal Cord Med 30: 473–476, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tanaka H, Shimizu S, Ohmori F, Muraoka Y, Kumagai M, Yoshizawa M, Kagaya A. Increases in blood flow and shear stress to nonworking limbs during incremental exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38: 81–85, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Theisen D, Vanlandewijck Y, Sturbois X, Francaux M. Central and peripheral haemodynamics in individuals with paraplegia during light and heavy exercise. J Rehabil Med 33: 16–20, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thijssen D, Green D, Steendijk S, Hopman M. Sympathetic vasomotor control does not explain the change in femoral artery shear rate pattern during arm-crank exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H180–H185, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thijssen D, Steendijk S, Hopman M. Blood redistribution during exercise in subjects with spinal cord injury and controls. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41: 1249–1254, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thijssen DH, Kooijman M, de Groot PC, Bleeker MW, Smits P, Green DJ, Hopman MT. Endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation of the superficial femoral artery in spinal cord-injured subjects. J Appl Physiol 104: 1387–1393, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]