Abstract

Objective To determine the prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among members of panels producing clinical practice guidelines on screening, treatment, or both for hyperlipidaemia or diabetes.

Design Cross sectional study.

Setting Relevant guidelines published by national organisations in the United States and Canada between 2000 and 2010.

Participants Members of guideline panels.

Main outcome measures Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among members of guideline panels and chairs of panels.

Results Fourteen guidelines met our search criteria, of which five had no accompanying declaration of conflicts of interest by panel members. 288 panel members had participated in the guideline development process. Among the 288 panel members, 138 (48%) reported conflicts of interest at the time of the publication of the guideline and 150 (52%) either stated that they had no such conflicts or did not have an opportunity to declare any. Among 73 panellists who formally declared no conflicts, 8 (11%) were found to have one or more. Twelve of the 14 guideline panels evaluated identified chairs, among whom six had financial conflicts of interest. Overall, 150 (52%) panel members had conflicts, of which 138 were declared and 12 were undeclared. Panel members from government sponsored guidelines were less likely to have conflicts of interest compared with guidelines sponsored by non-government sources (15/92 (16%) v 135/196 (69%); P<0.001).

Conclusions The prevalence of financial conflicts of interest and their under-reporting by members of panels producing clinical practice guidelines on hyperlipidaemia or diabetes was high, and a relatively high proportion of guidelines did not have public disclosure of conflicts of interest. Organisations that produce guidelines should minimise conflicts of interest among panel members to ensure the credibility and evidence based nature of the guidelines' content.

Introduction

The prevalence of financial conflicts of interest (COI) between clinicians and industry has been a topic of concern for the medical profession for more than two decades. The influence of COI on medical research and publishing has had recent attention,1 2 3 4 5 and the latest revelations about frequent and large “consultancy” payments to physicians, the practice of “ghost writing” by drug company employees, and the prevalence of industry funded “key opinion leaders” in medicine raise concern that physicians’ financial relations with industry may undermine the practice and promotion of high quality evidence based care.6 7 8 9 One area in which the presence of COI may be particularly concerning is the development of clinical practice guidelines.10 Guidelines serve to standardise care, to inform evidence based practice, and ultimately to protect patients, so their freedom from bias is particularly important.11 Over the past decade, most organisations that produce guidelines have adopted COI disclosure policies for members of guideline panels. Some organisations, such as the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), have gone further, excluding authors with COI from relevant decision making.12 In contrast to guidelines from centralised organisations such as NICE, US and Canadian guidelines are issued by medical specialty societies, non-profit organisations, government agencies, and professional associations, each with their own guideline development processes and COI disclosure policies.

Although most organisations mandate some form of disclosure, complete transparency is often not achieved,13 14 and simple disclosure of COI may not be enough to prevent panel members’ bias from influencing recommendations.11 15 16 Emphasising the importance of having unbiased recommendations to guide clinical practice, the Institute of Medicine recently published recommendations on management of COI among authors of clinical practice guidelines.17 These recommendations call for the exclusion of panel members with financial COI, the appointment of a chair without COI, and an end to direct funding of guidelines by industry. They also recommend full disclosure of the COI policy of each guideline panel, along with the potential COI of all panel members. Lastly, they recommend that if appointing panellists with COI is unavoidable, their presence should be limited to a minority and they should be prohibited from voting.

Using the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations as a framework, we determined the prevalence of financial COI among guideline panellists from organisations considered likely to reflect best clinical practice and influence behaviour. We evaluated guidelines produced over the past decade by national organisations in the United States and Canada that covered screening for and treatment of diabetes and hyperlipidaemia. We hypothesised that a substantial proportion of members of guideline panels would have COI. We chose hyperlipidaemia and diabetes as representative disease categories because of the high prevalence of both diseases in the population. In addition, the drugs used to treat these diseases account for the largest share of prescription drug expenditures within the US Medicare population and some of the highest spending on prescription drugs worldwide.18

Methods

We did a cross sectional study to examine the extent of financial COI among members of guideline panels who participated in the development of guidelines on hyperlipidaemia and diabetes between 2000 and 2010.

Sample

We identified guidelines by searching the National Guideline Clearinghouse, MDConsult, UpToDate, and the websites of organisations with a potential interest in hyperlipidaemia and diabetes (such as the American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, and American College of Physicians). We used the search terms “hyperlipidemia,” “cholesterol,” and “diabetes” to identify potential guidelines. We selected guidelines if they were issued by national organisations (government sponsored, medical specialty societies, professional associations, and non-profit organisations) in North America (United States and Canada), between 2000 and 2010 and covered screening, treatment, or both for hyperlipidaemia or diabetes in the general population. We classified each organisation exactly as listed on the National Guidelines Clearinghouse website, except for the Canadian Diabetes Association and the Canadian Cardiovascular Association, which were not included on this website. We used the designations of the US organisations most similar to them—the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. We excluded guidelines affiliated to a US state or Canadian province and those covering screening and management for particular subgroups of disease (for example, management of diabetes in patients with HIV) (table 1). We determined industry sponsorship of a guideline from acknowledgments in the guideline itself. The web appendix gives references for all the guidelines included.

Table 1.

Clinical practice guidelines for diabetes and hyperlipidaemia: panel members’ conflicts of interest (COI)*. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Guideline | Year issued | Organisation type† | No of panel members | COI declaration publicly available? | Chair with conflicts? | Declared conflicts | Conflicts identified by search | Total conflicts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes: | ||||||||

| VA/DoD clinical practice guideline | 2003 | Government | 23 | No | No | Unknown | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care‡ | 2005 | Government | 15 | Yes | Yes | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | 3 (20) |

| American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists | 2007 | Medical specialty society | 12 | Yes | Yes | 9 (75) | 1 (8) | 10 (83) |

| Canadian Diabetes Associationठ| 2008 | Professional association | 93 | Yes | Yes | 72 (77) | 1 (1) | 73 (78) |

| US Preventive Services Task Force | 2008 | Government | 16 | No | No | Unknown | 1 (6) | 1 (6) |

| Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement | 2010 | Non-profit | 15 | Yes | Yes | 6 (40) | 0 | 6 (40) |

| American Diabetes Association | 2010 | Professional association | 15 | Yes | NA | 13 (87) | 0 (0) | 13 (87) |

| Total | 189 | 101 (53) | 5 (3) | 106 (56) | ||||

| Hyperlipidaemia: | ||||||||

| American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists¶ | 2002 | Medical specialty society | 9 | No | No | Unknown | 1 (11) | 1 (11) |

| Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults | 2004 | Government | 9 | Yes | Yes | 8 (89) | 0 | 8 (89) |

| American Heart Association** | 2005 | Medical specialty society | 17 | Yes | Yes | 7 (41) | 0 | 7 (41) |

| VA/DoD clinical practice guideline | 2006 | Government | 13 | No | No | Unknown | 1 (7) | 1 (7) |

| US Preventive Services Task Force | 2008 | Government | 16 | No | No | 1 (6)†† | 1 (6) | 2 (13) |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society‡ | 2009 | Medical specialty society | 23 | Yes | NA | 20 (87) | 3 (13) | 23 (100) |

| Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement | 2009 | Non-profit | 12 | Yes | No | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 2 (17) |

| Total | 99 | 37 (37) | 7 (7) | 44 (44) | ||||

| Overall total | 288 | 138 (48) | 12 (4) | 150 (52) |

NA=no panel chair identified; VA/DoD=Veterans Administration/Department of Defense.

*Defined as direct compensation of guideline author by drug company in form of grants, speakers’ fees, honorariums, consultant/adviser/employee compensation, and stock ownership 2 years before and including year of guideline release.

†Classified exactly as listed on National Guidelines Clearinghouse website, except for Canadian Diabetes Association and Canadian Cardiovascular Association, which were not included on website; designations of US organisations most similar to them used—American Diabetes Association and American Heart Association.

‡Canadian guidelines.

§Drug company sponsors included GlaxoSmithKline, Novo, Sanofi, Servier Canada, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, and Hoffman-LaRoche, although document states that none of the authors was compensated in any way.

¶Drug company sponsors included Abbott Laboratories, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, KOS Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals, and Sankyo Parke-Davis.

**Other sponsoring organisations included councils on cardiovascular nursing, arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, vascular biology, basic cardiovascular sciences, cardiovascular disease in the young, clinical cardiology epidemiology and prevention, nutrition, physical activity and metabolism, and stroke and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association.

††No official COI document in guideline, but one author was noted to have been excused from voting because of his employment at Merck Pharmaceuticals.

Main outcome measure

We defined financial COI as the direct compensation of a guideline panellist by a manufacturer of a drug used to treat the disease of interest in the guideline, in the form of grants (including research), speakers’ fees, honorariums, consultant/adviser/employee relationships, and stock ownership. We classified COI into three categories: declared in the guideline; undeclared in the guideline but identified through our search strategy; and no opportunity to declare COI in the guideline but identified COI by our search strategy.

Identification of COI

We searched each guideline for declaration of COI by the panel members. If no conflict was declared in the guideline or in an accompanying document, we searched Medline to identify financial COI. We searched all publications of each panel member in the two years before publication and the year of publication of the guideline for data on COI. We used two years as the cut-off because organisations vary in the length of time they consider COI to be relevant. NICE considers COI to be relevant 12 months before participation on a committee,19 whereas the World Health Organization considers COI to be relevant within four years of participation.20

If the Medline search identified no COI, we used Google to search the internet, combining each panellist’s name with the name of each of the major manufacturers that develop and market drugs for hyperlipidaemia and diabetes. We searched for any relevant relations that occurred in the two years before release of the guideline. We identified drug companies by searching the Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2010 edition for all drugs listed for the treatment of hyperlipidaemia and diabetes and identifying their manufacturer by an internet search. We reviewed the first 50 search results for each panellist-drug company pair for reported financial relations with the drug industry. We chose a threshold of 50 results because search results became less relevant after this threshold. When we identified COI, we confirmed the identity of the panel member of interest by matching his or her reported institutional affiliation with the one documented in the guideline. One author (JN) identified COI, and another (SK) verified the presence of COI.

Statistical analysis

We report the percentage of panel members with financial COI and whether the chair of the panel had COI. We report the types of compensation received by panellists but distinguish grant funding from other types of compensation, as it presumably is intended to support research efforts whereas other forms of compensation generally support personal income. In a secondary analysis, we dichotomised guidelines into several categories, including sponsorship (government versus other), disease (hyperlipidaemia versus diabetes), and country of origin (United States versus Canada). We created these categories to examine the effect of the characteristics of the organisation sponsoring the guidelines on the prevalence of reported COI. We compared the proportion of COI in each guideline category overall and in a secondary sensitivity analysis, limiting the sample to guidelines with declarations of COI to account for possible bias related to opportunity for disclosure. We examined differences between each category by using a two sided, 0.05 level χ2 test of significance. We used Stata statistical software for all statistical analyses.

Results

Characteristics of guidelines

We identified 14 guidelines that met our search criteria: seven for diabetes and seven for hyperlipidaemia (table 1). Four of the guidelines were published by medical specialty societies, two were from professional associations, six were from government sponsored organisations, and two were published by private non-profit organisations. Three guidelines were from Canada and 11 from the United States. Two guideline producing organisations had drug industry sponsorship (one from Canada and one from the United States). Among the 14 guideline producing organisations, nine provided a document listing the COI of panellists. Five guidelines did not provide an opportunity for panellists to publicly declare financial COI, and four of these were sponsored by the government.

Panel size

The size of panels ranged from nine to 93, with a median size of 15 panellists per guideline. A total of 288 panel members, representing 265 different people, participated in the 14 guidelines. Twenty-three panel members participated in two guidelines. Of these panel members, five had COI that were counted for both guidelines, two had COI that counted for only one of the guidelines, and 16 had no COI. Among the 23 panellists who were counted twice, 17 had no opportunity to publicly declare COI.

Prevalence of financial COI

Of the 288 panel members (chairs included), 48% (n=138) reported COI at the time of the publication of the guideline and 52% (150) either stated that they had no COI (73) or did not have an opportunity to declare COI (77) (table 1). Of those who declared conflicts, 93% (128) reported receiving honorariums, speakers’ fees, employee/adviser/consultancy payments, or stock ownership from drug manufacturers of interest. The remaining 7% (10) reported receiving funding exclusively for research.

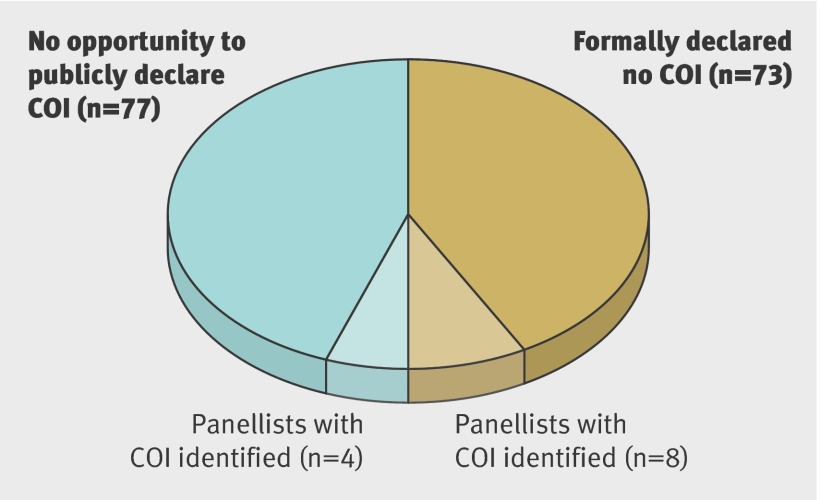

Of the 211 panellists who had an opportunity to publicly declare COI, 73 stated that they had no COI, among whom 11% (n=8) had undeclared COI identified through our search strategy (fig 1). All 73 panel members received speakers’ fees, honorariums, or employee/adviser/consultancy payments or held stock ownership. Among the 77 panel members who did not have an opportunity to publicly declare COI, we found 5% (4) to have COI through our search strategy (fig 1). Of the 12 undeclared COI, we found one through our Google search and the remainder through our Medline search. In summary, among 288 members of guideline panels, 52% (n=150) had COI, of which 138 were declared and 12 undeclared. Four undeclared conflicts were among panel members of guidelines without an opportunity to declare COI.

Panellists with no declaration of conflicts of interest (COI) (n=150)

Of the 14 guidelines, 12 identified a chair. Of these 12, we found six to have COI, all of which were declared. Among guidelines that provided public declarations of COI, six of seven chairs reported COI (table 1).

Conflicts of interest by guidelines’ characteristics

COI were significantly less common among guideline panels sponsored by the government than among panels sponsored by other organisations (16% v 69%; P<0.001) (table 2). COI were highly prevalent among panel members of guidelines produced by Canadian specialty societies and US specialty societies but were significantly higher among Canadian panels (83% v 58%; P<0.001). We found no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of COI among panel members of diabetes compared with hyperlipidaemia guidelines (56% v 44%; P=0.06). In a sensitivity analysis limited to guidelines for which panellists had the opportunity to publicly declare conflicts, we found that COI were still significantly less common among guideline panels sponsored by the government compared with panels sponsored by other organisations (46% v 72%; P=0.01) (table 2). COI were significantly more common among Canadian than US panels (83% v 68%; P=0.04), and again we found no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of COI among panel members of diabetes compared with hyperlipidaemia guidelines (table 2).

Table 2.

Reported financial conflicts of interest (COI) among panel members by category of guideline sponsor

| Characteristic of guideline | All guidelines | Guidelines with declared COI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of guidelines | No of panel members | No (%) panel members with COI | P value | No of guidelines | No of panel members | No (%) panel members with COI | P value* | ||

| Diabetes | 7 | 189 | 106 (56) | 0.06 | 5 | 150 | 105 (70) | 0.52 | |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 7 | 99 | 44 (44) | 4 | 61 | 40 (66) | |||

| Government | 6 | 92 | 15 (16) | <0.001 | 2 | 24 | 11 (46) | 0.01 | |

| Other* | 8 | 196 | 135 (69) | 7 | 187 | 134 (72) | |||

| US specialty† | 4 | 53 | 31 (58) | <0.001 | 3 | 44 | 30 (68) | 0.04 | |

| Canadian specialty | 2 | 116 | 96 (83) | 2 | 116 | 96 (83) | |||

*All non-government sponsored guidelines included in this category.

†Includes organisations designated as “medical specialty” or “professional associations” on National Guidelines Clearinghouse website.

Discussion

For diabetes and hyperlipidaemia, we found that conflicts of interest (COI) were present for the vast majority of guideline panels reviewed. We also found that among panels that had chairs, half of these had COI. In addition, among panellists with an opportunity to publicly report COI, one out of nine reported no COI but were found to have undeclared COI. Our data illustrate the pervasiveness of COI among members of guideline panels and may raise questions about the independence and objectivity of the guideline development process in the United States and Canada.

A recent study of COI for members of cardiovascular guideline panels also found that COI were common.21 However, this study was limited to guidelines produced by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, an organisation whose guideline development process has previously been scrutinised for influence by industry.22 Our study includes a wide range of guideline producing organisations and can be applied to the general guideline development process in the United States and Canada. Furthermore, our study exposes the problem of incomplete disclosure and highlights the important relation between sponsorship of guidelines and presence of COI. Our results are similar to those of a study done more than a decade ago, which found that 59% of authors of guidelines admitted to having received funding from manufacturers whose products were included or considered in the guideline. However, only two of 44 guidelines studied at that time had publicly available disclosure documents, and COI were documented only through self report.23 Our study shows that in spite of increasing requirements for disclosure of COI by guideline panellists the rate of COI remains similar, suggesting that mandating transparency may not translate into decreased COI on guideline panels.

Among guideline sponsoring organisations with public disclosure of COI, we found that government sponsored panels had significantly fewer panel members with COI, suggesting that expert panels can be convened from members predominantly without COI. However, although our sample included six government sponsored guidelines, only two of them (one Canadian and one US) included a public statement on the COI of panel members. The remaining four were produced by the Veterans Administration and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). The USPSTF is the main government sponsored body in the United States that issues guidelines on screening and has a strict policy of managing its members’ conflicts of interest.24 However, task force panel members’ COI disclosures can be viewed only after a request under the Freedom of Information Act is filed with the government. This process is unnecessarily cumbersome and does not lend itself to easy scrutiny of this information by providers or the public. Similarly, the Veterans Administration does not disclose its panel members’ COI. In contrast to the USPSTF, the Veterans Administration presents no apparent official policy on the management of COI among panel members. This is in contrast to NICE, which provides detailed policies and procedures on disclosure as well as COI declarations on its website.16 Although this lack of full transparency by government sponsored panels in the United States is troubling, our search identified only three members of USPSTF and Veterans Administration guideline panels with undeclared financial COI, suggesting that COI are managed well on government sponsored panels.

In contrast to government sponsored panels, we found that COI were very common among panel members for guidelines produced by specialty societies. Guidelines produced by non-government sponsored organisations have been shown to be of poor methodological quality25; however, they contribute substantially to the guideline pool in the United States and Canada, with specialty societies alone accounting for almost 40% of guidelines in the National Guideline Clearinghouse.17 Furthermore, several of the specialty societies included in our review have international prominence outside of North America, and their guidelines may have broad international influence. The high prevalence of COI among panel members of guidelines sponsored by specialty societies combined with the less rigorous development process may adversely affect the independence and the evidence base of the recommendations issued.26

Limitations

Our study has several strengths and limitations that deserve comment. Five panel members’ conflicts were counted twice because our reporting of COI was based on panel membership and was not limited to unique individuals. If we had reported COI on the basis of the 265 unique individuals who participated in the process, our declared COI rate would have been 50% (n=133). This alternative analysis would not change the implications of our findings. We compared the prevalence of COI among government sponsored guidelines with that of non-government sponsored guidelines, and many government sponsored guidelines did not have accompanying declarations of COI. However, to identify potential conflicts we did a comprehensive Medline and Google search for each panel member. In addition, to account for potential bias related to opportunity for disclosure, we did a sensitivity analysis and limited the sample to guidelines with disclosed COI. This analysis confirmed our finding that COI were less prevalent among guidelines sponsored by the government.

We also note that our methods were deliberately conservative and may have underestimated COI among guideline panellists. We considered a financial conflict of interest to be present only when clear documentation of compensation of the panellist by a manufacturer of a product mentioned in a guideline was present. For the two guidelines in our study that were directly sponsored by drug companies, we searched each panel member individually for COI, rather than assuming they had received compensation for their work on the guideline. We also found that many members of guideline panels were authors of papers reporting on industry sponsored clinical trials or had chaired industry sponsored conferences. We did not count these relationships as financial conflicts; however, these panel members probably received funding from industry. We also did not include financial conflicts that did not relate directly to a guideline’s content or that did not directly involve the panel member of concern. For example, if a panel member’s spouse was an employee of the drug industry, we did not consider it a conflict. We were also unable to account for relationships with industry that were not publicly available and did not search for additional conflicts if one was already declared. Both of these factors probably limited the number and scope of COI found in our study.

Finally, our sample size was limited to only two disease conditions. However, together, these two conditions are predicted to be among the top five drug treatment categories in the world by 2015, with combined consumer spending of up to $82bn (£52bn; €59bn).27 Furthermore, our results are more generalisable than are those of other recent studies of its kind. In contrast to the recent paper by Mendelson et al,21 which focused on one guideline producing organisation, our study sample included guidelines from many different organisations, which provides a more realistic estimate of the prevalence of COI on guideline panels.

Conclusions

The finding that most current members of guideline panels and half of chairs of panels have COI is concerning and suggests that a risk of considerable influence of industry on guideline recommendations exists. The Institute of Medicine recently recommended that guideline panels should be as conflict-free as possible,17 The minimisation of COI on guideline panels is likely to do far more to mitigate bias than would mere disclosure. The guideline development process needs to be reformed to minimise conflicts of interest among panel members to ensure the credibility and evidence based nature of the clinical practice guidelines issued in the United States and Canada. The limited COI we identified among panel members who participated in developing government sponsored guidelines suggests that expert panels without many COI can be convened. Future research should examine whether the presence of COI diminishes in the light of the international trend, articulated by the Institute of Medicine, towards both transparency and exclusion of panel members with COI. Conflict-free guideline panels are feasible and would help to improve the quality of the guideline development process.

What is already known on this topic

Conflicts of interest (COI) among panel members are common in guidelines issued by certain specialty organisations

What this study adds

The prevalence and under-reporting of COI are high and transparency is incomplete among a wide range of guideline producing organisations

An association exists between the source of sponsorship of guidelines and the presence of COI

Contributors: JN and SK conceived the study. JN, SK, JSR, and DK designed the study. JN collected the data. SK verified the data. JN and SK analysed and interpreted the data. JN and SK wrote the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript. JN is the guarantor.

Funding: This project was not directly supported by any research funds. SK is funded by a Veterans’ Administration HSR&D career development award. JSR is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG032886) and by the American Federation of Aging Research through the Paul B Beeson Career Development Award Program.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Data sharing: All data on members of guideline panels are publicly available. Dataset available from corresponding author on request.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d5621

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

References

- 1. Roseman M, Milette K, Bero LA, Coyne JC, Lexchin J, Turner EH, et al. Reporting of conflicts of interest in meta-analyses of trials of pharmacological treatments. JAMA 2011;305:1008-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:1167-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang AT, McCoy CP, Murad MH, Montori VM. Association between industry affiliation and position on cardiovascular risk with rosiglitazone: cross sectional systematic review. BMJ 2010;340:c1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lundh A, Barbateskovic M, Hrobjartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Conflicts of interest at medical journals: the influence of industry-supported randomised trials on journal impact factors and revenue—cohort study. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drazen JM, de Leeuw PW, Laine C, Mulrow C, Deangelis CD, Frizelle FA, et al. Towards more uniform conflict disclosures: the updated ICMJE conflict of interest reporting form. BMJ 2010;340:c3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chimonas S, Frosch Z, Rothman DJ. From disclosure to transparency: the use of company payment data. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:81-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross JS, Hill KP, Egilman DS, Krumholz HM. Guest authorship and ghostwriting in publications related to rofecoxib: a case study of industry documents from rofecoxib litigation. JAMA 2008;299:1800-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moynihan R. Key opinion leaders: independent experts or drug representatives in disguise? BMJ 2008;336:1402-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stelfox HT, Chua G, O’Rourke K, Detsky AS. Conflict of interest in the debate over calcium-channel antagonists. N Engl J Med 1998;338:101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holloway RG, Mooney CJ, Getchius TS, Edlund WS, Miyasaki JO. Conflicts of interest for authors of American Academy of Neurology clinical practice guidelines. Neurology 2008;71:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guyatt G, Akl EA, Hirsh J, Kearon C, Crowther M, Gutterman D, et al. The vexing problem of guidelines and conflict of interest: a potential solution. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:738-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinbrook R. Guidance for guidelines. N Engl J Med 2007;356:331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosgrove L, Bursztajn HJ, Krimsky S, Anaya M, Walker J. Conflicts of interest and disclosure in the American Psychiatric Association’s clinical practice guidelines. Psychother Psychosom 2009;78:228-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okike K, Kocher MS, Wei EX, Mehlman CT, Bhandari M. Accuracy of conflict-of-interest disclosures reported by physicians. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1466-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development. WHO, 2008.

- 16.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Code of practice for declaring and dealing with conflicts of interest: NICE, 2008.

- 17.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Conflict of Interest in Medical Research EaP. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. National Academies Press, 2009. [PubMed]

- 18.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Household and pharmacy components of the medical expenditure panel survey. AHRQ, 2007.

- 19.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Are you taking part in a NICE advisory body meeting? Do you have a conflict of interest you need to declare? 2007. www.nice.org.uk/media/134/39/CodePractice2AdvisoryBodyQuickGuide.pdf.

- 20.World Health Organization. Declaration of interests for WHO experts. 2010. http://keionline.org/node/1062. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Mendelson TB, Meltzer M, Campbell EG, Caplan AL, Kirkpatrick JN. Conflicts of interest in cardiovascular clinical practice guidelines. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:577-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC Jr. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA 2009;301:831-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhry NK, Stelfox HT, Detsky AS. Relationships between authors of clinical practice guidelines and the pharmaceutical industry. JAMA 2002;287:612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Preventive Services Task Force. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force procedure manual. USPSTF Program Office, 2011.

- 25.Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A, Mura G, Liberati A. Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal. Lancet 2000;355:103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keyhani S, Kim A, Mann M, Korenstein D. A new independent authority is needed to issue national health care guidelines. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:256-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. The global use of medications outlook through 2015. IMS, 2011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.