Abstract

The regulation of Protein Kinase B (AKT) is a dynamic process that depends on the balance between phosphorylation by upstream kinases for activation and inactivation by dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases. Phosphorylated AKT is commonly found in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and confers an unfavorable prognosis. Understanding the relative importance of upstream kinases and AKT phosphatase in the activation of AKT is relevant for the therapeutic targeting of this signaling axis in AML. The B55α subunit of Protein Phosphatase 2A (PP2A) has been implicated in AKT dephosphorylation but its role in regulating AKT in AML is unknown. We examined B55α protein expression in blast cells derived from 511 AML patients using Reverse Phase Protein Analysis (RPPA). B55α protein expression was lower in AML cells compared to normal CD34+ cells. B55α protein levels negatively correlated with T308 phosphorylation levels. Low levels of B55α were associated with shorter complete remission duration demonstrating that decreased expression is an adverse prognostic factor in AML. These findings suggest that decreased B55α expression in AML is at least partially responsible for increased AKT signaling in AML and suggests that therapeutic targeting of PP2A could counteract this.

Keywords: PP2A, AKT, AML, B55 alpha

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains highly fatal highlighting the need for improved understanding of leukemia pathophysiology that can lead to targeted therapies with greater efficacy. Strategies to target signal transduction pathways that support tumor cell growth and survival have been suggested as a way to optimize AML therapy1–8. Activation of survival kinases such as Protein Kinase B (AKT), Protein Kinase C (PKC), and Extracellular Receptor Activated Kinase (ERK) has been shown to predict poor clinical outcome for patients with AML8. AKT is a key regulator of protein translation, transcription, cell proliferation and apoptosis that may have as many as 9000 substrates and is emerging as a potentially important target for AML therapy1, 3, 4, 8. AKT substrates include mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR), Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β (GSK3β), and FOXO3A. AKT is activated by a Phosphatidylinositol 3 Kinase (PI3K)/Phosphatidylinositol Dependent Kinase 1 (PDK1) cascade that promotes phosphorylation of the kinase on threonine 308 (T308) and serine 473 (S473)3, 5. A recent study has indicated that phosphorylation of AKT at T308 but not S473 is a poor prognostic factor for AML patients9.

The regulation of signal transduction is a dynamic process dependent on the balance between phosphorylation by protein kinases and dephosphoryaltion by protein phosphatases10, 11. Aberrant activation of AKT in a leukemia cell could result from either the abnormal activation of upstream AKT activators like PI3K or the relative loss of AKT phosphatase activity, but the relative importance of each it is currently unknown. The Protein Phosphatase 2A (PP2A) has been implicated as a major AKT phosphatase11–13. The loss of PP2A has been implicated in cellular transformation suggesting that PP2A is a probable tumor suppressor.14, 15PP2A is a hetero-trimer consisting of a catalytic C subunit, a scaffold A subunit, and one of at least 21 different regulatory B subunits. Thus PP2A is not a single enzyme but rather a family of different isoforms. The functionality and substrate specificity of each PP2A isoform is determined by the regulatory B subunit it contains16–22. In addition, the B subunit influences substrate selection by directing sub-cellular localization of the PP2A catalytic complex19–22. Evidence suggests that the B55α PP2A subunit (gene name PPP2R2A) is responsible for dephosphorylation of AKT at T30813. Consequently an understanding of how PP2A regulates AKT in AML cells may be important to understand how increased AKT activation (phosphorylation) arises in AML. At present little is known about the role of PP2A in AML. In the current study, we examined B55α expression in a cohort of 511 AML patients by reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) and found that B55α (a) was found to be expressed at lower levels in AML blasts compared to counterpart cells (i.e. CD34+) derived from normal donors, (b) negatively correlated with AKT T308 phosphorylation, and (c) correlated with shorter complete remission (CR) duration in AML patients. These findings suggest that B55α is involved in the regulation of pAKT levels and activity in AML and suggest that therapeutically targeting PP2A activity might interrupt the increased AKT pathway activity seen in AML.

Material and Methods

Patient Samples

Peripheral blood and bone marrow specimens were collected from 511 patients with newly diagnosed AML evaluated at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) between September 1999 and March 2007. Samples were acquired during routine diagnostic assessments in accordance with the regulations and protocols (Lab 01–473) approved by the Investigational Review Board of MDACC. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helinski. Samples were analyzed under and Institutional Review Board–approved laboratory protocol (Lab 05–0654). Patient characteristics and sample preparation were previously described23.

Gene Expression Analysis

To ensure complete removal of trace genomic DNA or other factors that could interfere with downstream enzymatic processes (i.e., heparin anticoagulant), all RNA samples were subjected to final purification using RNeasy Mini Columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with on-column treatment by DNAse I as directed by the manufacturer. We prepared cDNA from 1.0 µg of total RNA per 20 µL mix containing 0.07 µg/µL random-sequence hexamer primers, 1 mM dNTPs, 5 mM DTT, 0.2 u/µL SuperAsin RNAse inhibitor (Ambion, Austin, TX), and 10 u/µL SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA and primers were denatured 5 minutes at 70° C and then chilled on ice. All components except enzyme were added and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 minutes to allow nucleic acids to anneal. After addition of reverse transcriptase, the mixture was incubated for ten minutes at 25° C, then one hour at 50° C, followed by heat-inactivation of the enzyme for 15 minutes at 72° C. All cDNAs were stored at −80 C when not in use. To verify the complete removal of any residual genomic material in the real-time PCR assays, we incubated in parallel 1.0 µg of total RNA per 20 µl of a mix containing all components except reverse transcriptase.

We carried out real time PCR using an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). We ran duplicate 25 µl reactions containing 0.5 µl cDNA; reactions were repeated if the Ct values were more than 0.25 cycles apart. As primers and probes we used TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) specific for the genes of interest in this study (Table 1) as directed by the manufacturer. We used ABL as a housekeeping gene to normalize gene expression. To calculate the relative abundance (RA) of each transcript of interest relative to that of ABL, the following formula was employed: RA = 100 × 2[−ΔCt], where ΔCt is the mean Ct of the transcript of interest minus the mean Ct of the transcript for ABL. The Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test was used to test for a difference in gene expression of PP2A subunits between normal CD34+ bone marrow cells and blast cells from AML patients. Differences were considered statistically significant when p≤ 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with Sigma Stat computer software (SSPS, Chicago, IL).

Table 1.

List of PP2A subunit genes and ABL1 control analyzed using Real-Time PCR with Applied Biosystems (ABI) Taqman assays.

| Common name | Symbol | Chromosome location |

ABI assay ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP2A A α | PPP2R1A | 19q13.41 | Hs00204426_m1 |

| PP2A A β | PPP2R1B | 11q23.2 | Hs00184737_m1 |

| PP2A B55 α | PPP2R2A | 8p21.2 | Hs00160392_m1 |

| PP2A C α | PPP2CA | 5q31.1 | Hs00427259_m1 |

| PP2A C β | PPP2CB | 8p12 | Hs00602137_m1 |

| ABL1 | ABL1 | 9q34.1 | Hs00245445_m1 |

RPPA method

Proteomic profiling was done on samples from patients with AML using RPPA. The method and validation of the technique are fully described in previous publications7, 23. Briefly, patient samples were printed in five serial dilutions onto slides along with normalization and expression controls. Slides were probed with strictly validated primary antibodies. Antibodies against total AKT protein, AKT phosphorylated at T308, AKT phosphorylated at S473, total S6K protein, S6K phosphorylated at T389, total BAD protein, and BAD phosphorylated at S136 were obtained from Cell Signaling and have been previously described7. The antibody recognizing PP2A B subunit protein B55 α was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA; catalog # 18830. A IgG subtype specific secondary antibody was used to amplify the signal and finally a stable dye is precipitated. The stained slides were analyzed using the Microvigene software (Vigene Tech) to produce quantified data.

Statistical analysis

For RPPA, supercurve algorithms were used to generate a single value from the five serial dilutions24. Loading control and topographical normalization procedures accounted for protein concentration and background staining variations25. Analysis using unbiased clustering perturbation bootstrap clustering, and principle component analysis was then done as fully described in a previous publication7. Variables were divided into sixths based on the range of expression of all 511 samples. Comparison of the protein levels between paired samples was done by performing paired t test. Association between protein expression levels and categorical clinical variables were assessed in R using standard t tests, linear regression, or mixed effects linear models. Association between continuous variable and protein levels were assessed by using the Pearson and Spearman correlation and linear regression. Bonferroni corrections were done to account for multiple statistical parameters for calculating statistical significance. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to generate the survival curves. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard modeling was done to investigate association with survival with protein levels as categorized variables using the Statistica version 9 software (StatSoft, Tulsa OK). Although some molecular markers (NPM1, FLT3-ITD and RAS mutations) are known for this dataset other more recently discovered prognostic markers (e.g.DNMT3A, CEBPα, Wilms Tumor 1) are not ; therefore, the multivariate analysis did not contain all known AML prognostic markers. Overall survival was determined based on the outcome of 415 newly diagnosed AML patients treated at UTMDACC and remission duration was based on the 231 patients that achieved remission.

Results

B55α levels are lower in blast cells from AML patients compared to normal CD34+ counterpart cells

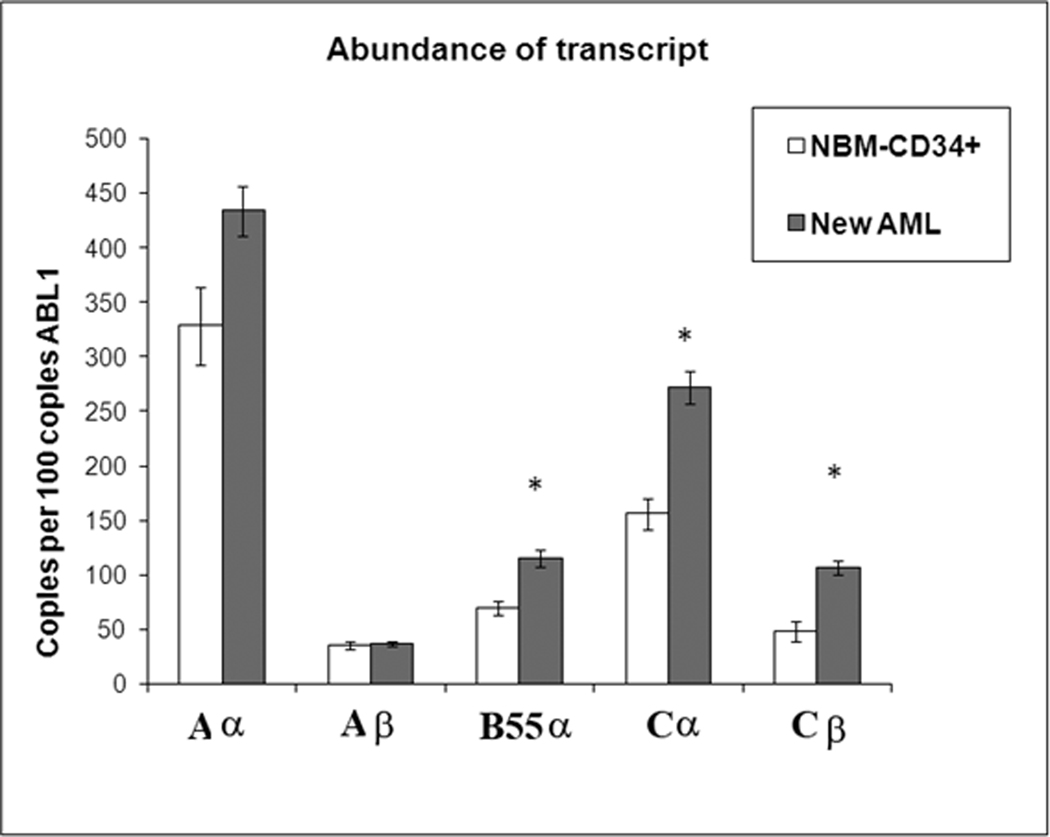

We surveyed the relative abundance of B55α transcript among 30 patients newly diagnosed with AML and 6 bone-marrow transplant donors using real time PCR. We included assays for both known A scaffold subunits (i.e. Aα and Aβ), both known C catalytic subunits (i.e. Cα and Cβ), and the B55α regulatory subunit (Table 1). Relative expression of the PP2A subunits in Normal BM and AML blast cells is depicted in Figure 1. There was no significant difference in the expression of either scaffold gene when comparing AML blast cells and normal BM cells (p > 0.05 in both cases; Table 2). As shown in Figure 1, expression of both catalytic C subunits was elevated in AML blast cells versus normal BM cells (> 2 fold for Cα; p = 0.012; and > 2 fold for Cβ; p= 0.10; Table 2). Gene expression of B55α was significantly elevated (~ 1.5 fold; p = 0.038; Table 2) in the AML blast cells compared to the normal counterpart cells. This finding was surprising as a prominent feature of AML is constitutive activation of proliferation pathways including the PI3K/AKT pathway4–9, 23. Because B55α negatively regulates AKT13, the observed relative increase in gene transcription of the PP2A B subunit in the AML blast cells is not consistent with the expectation that AKT is active in the leukemia cells4–9, 23. An obvious explanation for this finding is that the transcription rate of the B55α gene may be high but the level of protein is low due to different rates of translation, degradation, cleavage, or post-translational inactivation. To resolve this question, we looked at protein expression in the AML blast cells compared to normal counterpart cells.

Figure 1. PP2A gene expression is generally elevated in AML blast cells compared to normal CD34+ bone marrow cells.

Real Time PCR was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. Expression of PPP2R1A (A α), PPP2R1B (A β), PPP2R2A (B55 α), PPP2CA (C α), and PPP2CB(C β) genes are presented as relative to 100 copies of ABL1for CD34+ cells derived from bone marrow from normal donors (N = 6) and blast cells derived from AML patients (N= 75). The p values were derived as described in “Materials and Methods”. Statistically significant differences from expression in normal bone marrow cells (p < 0.05) are marked with *.

Table 2.

Expression of PP2A genes in normal CD34+ and AML blast cells.

| Gene | Group | Mean Rank | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP2A A α | Normal CD34+ | 13.17 | .174 |

| AML | 19.57 | ||

| PP2A A β | Normal CD34+ | 21.33 | .471 |

| AML | 17.93 | ||

| PP2A B55 α | Normal CD34+ | 10.33 | .038* |

| AML | 20.13 | ||

| PP2A C α | Normal CD34+ | 8.67 | .012* |

| AML | 20.47 | ||

| PP2A C β | Normal CD34+ | 8.33 | .010* |

| AML | 20.53 |

Mann-Whitney test

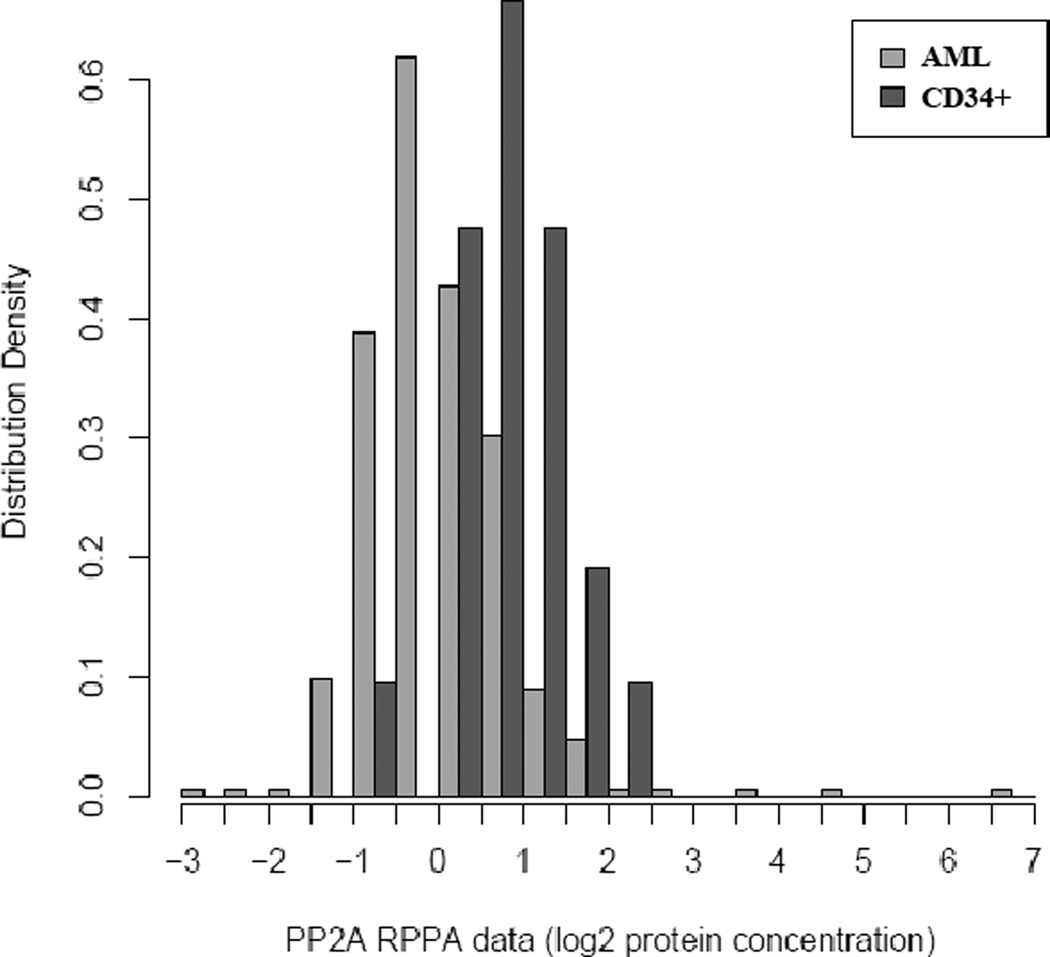

RPPA is a powerful tool that allows for the analysis of protein expression from samples when not much material may be available. Many clinical samples fit this category. The only caveat is that a validated antibody must be available for the protein of interest. We used RPPA to study the PP2A substrate specificity defining B55 α protein in AML blast cells obtained from 511 newly diagnosed AML patients and CD34+ cells obtained from 21 normal bone marrow donors. We compared expression of the B subunit in the AML patient set with expression in normal CD34+ cells. Levels of B55α protein were significantly (p <0.001) lower in the blast cells from the AML patients compared to normal CD34+ cells as shown in the histogram in Figure 2. The reduced relative protein expression of the B subunit observed in the leukemia cells is in contrast with the relative elevation of gene expression observed in Figure 1. While the mechanism for the observed difference in gene versus protein expression in the leukemia cells has yet to be determined, a plausible mechanism is that the B55α protein is being translated less efficiently or that the protein is being proteolyzed more rapidly. It is well established that PP2A is an obligate hetero-trimer and that PP2A B subunits are proteolyzed when not in a complex with the catalytic core (i.e. monomeric PP2A subunit protein is degraded)18, 26.

Figure 2. B55 α protein expression is lower in AML blast cells compared to normal counterpart CD34+ cells.

RPPA was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. Expression of B55 α was compared in blast cells from 511 AML patients versus CD34+ bone marrow cells from 21 normal donors.

B55α levels negatively correlate with T308 AKT phosphorylation levels in AML blast cells

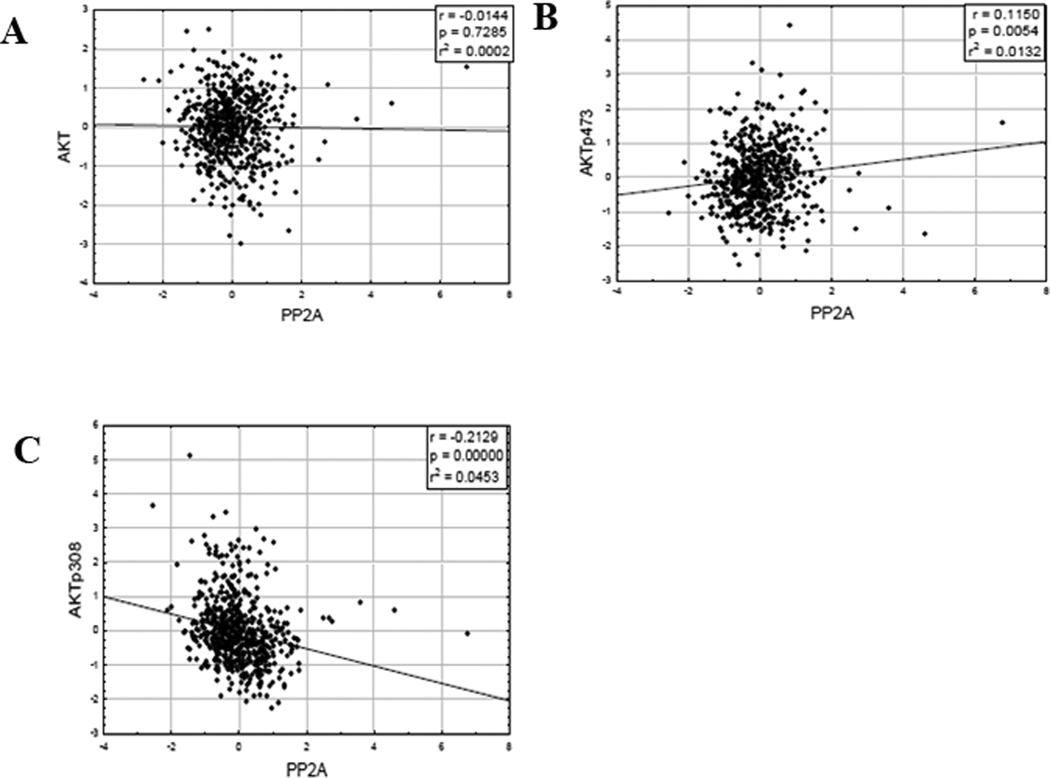

A reduction of B55α protein would be predicted if AKT were activated. A comparison of AKT phosphorylation status and B55α protein expression in the AML blast cells would answer this question. Considering the clinical significance of T308 phosphorylation of AKT9 and the implication that the B55 α subunit controls the PP2A isoform that acts as the AKT phosphatase, we were interested in whether the B subunit was responsible for dephosphorylation of AKT at T308 in the AML samples. There was no correlation between B55 α protein levels and levels of total AKT protein the AML samples (Figure 3A; r = −0.0293, p= 0.5202) or with levels of AKT phosphorylated at S473 (Figure 3B; r= 0.0822, p= 0.0711). However as shown in Figure 3C, there was a moderate but significant negative correlation between B55 α protein levels and levels of AKT phosphorylated at T308 (r = −0.2269, p < 0.0001). This result suggests that B55 α is mediating dephosphorylation of AKT at T308 but not S473 in the AML cells.

Figure 3. B55 α protein expression negatively correlates with T308 but not S473 phospho-AKT in AML blast cells.

RPPA was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. Expression of B55 α was compared to total AKT (A), AKT phosphorylated at S473 (B), and AKT phosphorylated at T308 (C).

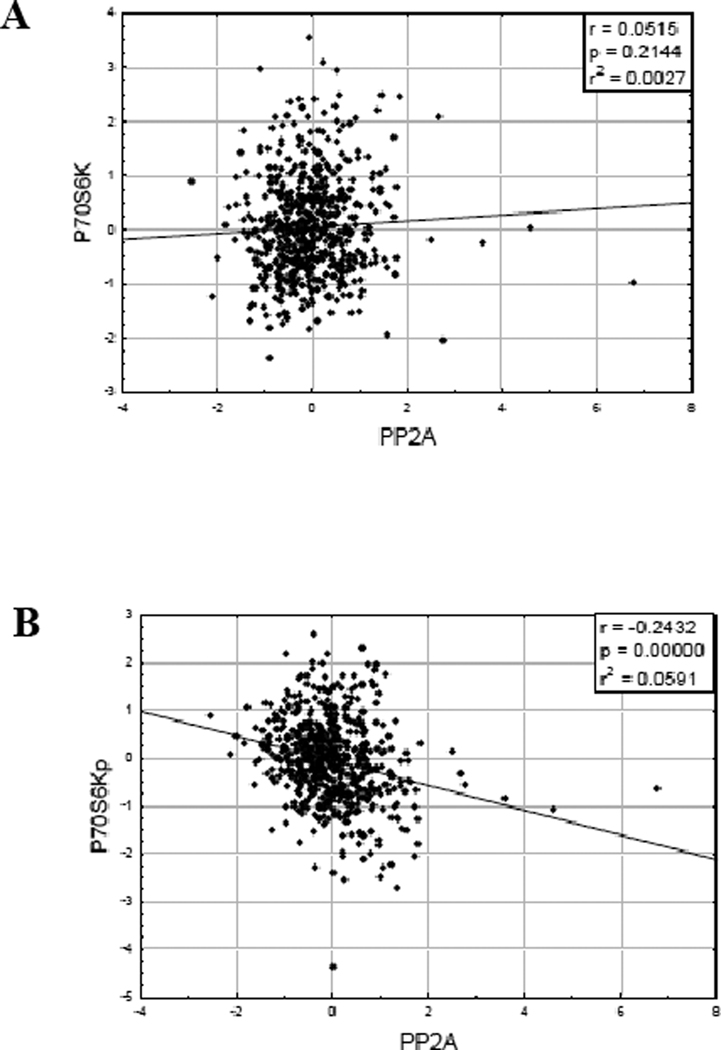

B55α levels are negatively correlated with P70S6 Kinase phosphorylation levels in AML blast cells

S6 Ribosomal Kinase (S6K) serves as a negative feedback regulator of AKT and is phosphorylated when mTOR Complex I is activated1, 4, 5. If B55α is suppressing AKT activity by dephosphorylating the kinase, we would expect that levels of B55 α in the AML patients would negatively correlate with phosphorylation levels of p70S6 Kinase12. B55α displayed a moderate negative correlation with phosphorylated p70S6 Kinase at T389 (Figure 4A; r = 0.2696; p < 0.0001) but not total p70S6 Kinase protein the AML samples (Figure 4B; r = −0.0585; p= 0.3314).

Figure 4. B55 α protein expression negatively correlates with T389 phospho-p70S6 Kinase in AML blast cells.

RPPA was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. Expression of B55 α was compared to total p70S6 Kinase (A) and p70S6 Kinase phosphorylated at T389 (B).

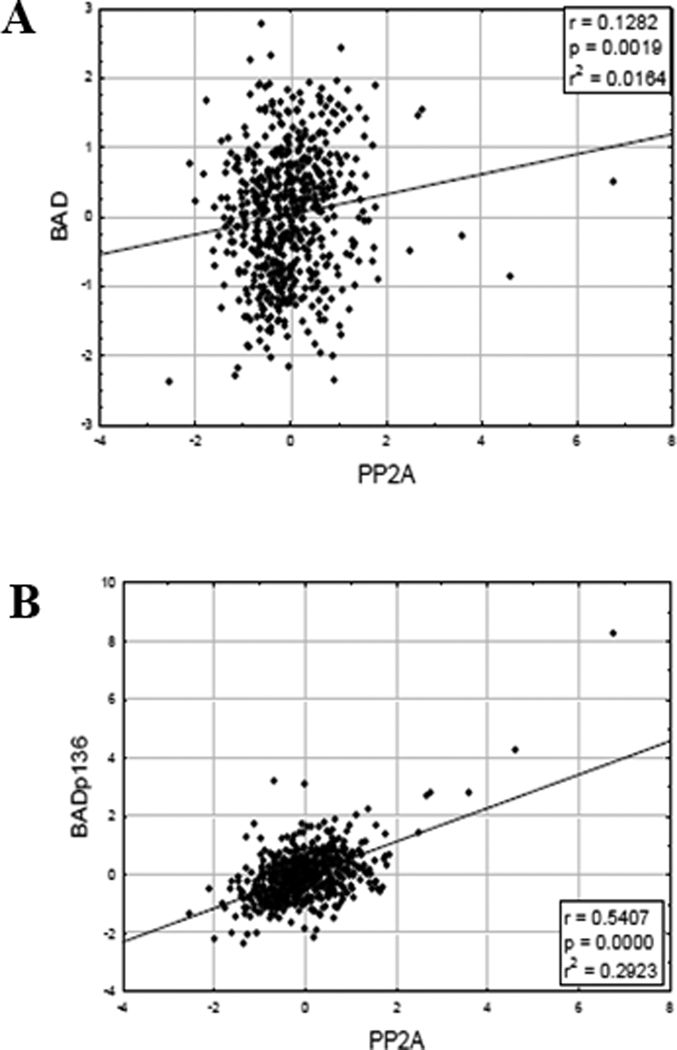

B55α levels positively correlate with BAD S136 phosphorylation levels in AML blast cells

Activated AKT has been shown to phosphorylate and inactivate the pro-apoptotic BCL2 family member BAD at S1364. A correlation betweenB55 α protein and total BAD levels was not observed (Figure 5A; r = 0.1417; p = 0.0018). Surprisingly, B55α displayed a strong positive correlation with BAD phosphorylated at S136 (Figure 5A; r = 0.5209; p < 0.0001). Assuming AKT acts as the kinase to phosphorylate BAD at S136 in the AML patients, we would have predicted higher levels of S136 phosphorylated in patients with low B55 α levels (i.e. AKT would be more active in the absence of its phosphatase). However, other kinases (e.g. various PKC isoforms30) have been implicated in the phosphorylation of BAD at S136 and thus it is possible that AKT is not the major BAD kinase in AML. That a positive correlation between phosphorylation of BAD at serine 136 and B55α expression was observed suggests that B55α is not the phosphatase to dephosphorylate BAD at S136. As discussed earlier, PP2A is an obligate heterotrimer so when expression of B55 α is higher, there would be lower expression of other PP2A B subunits and one or more of these proteins are likely responsible for dephosphorylation of BAD at S136.

Figure 5. B55 α protein expression positively correlates with S136 phospho-BAD in AML blast cells.

RPPA was performed as described in “Materials and Methods”. Expression of B55 α was compared to total BAD phosphorylated at S136 (A) and total BAD (B).

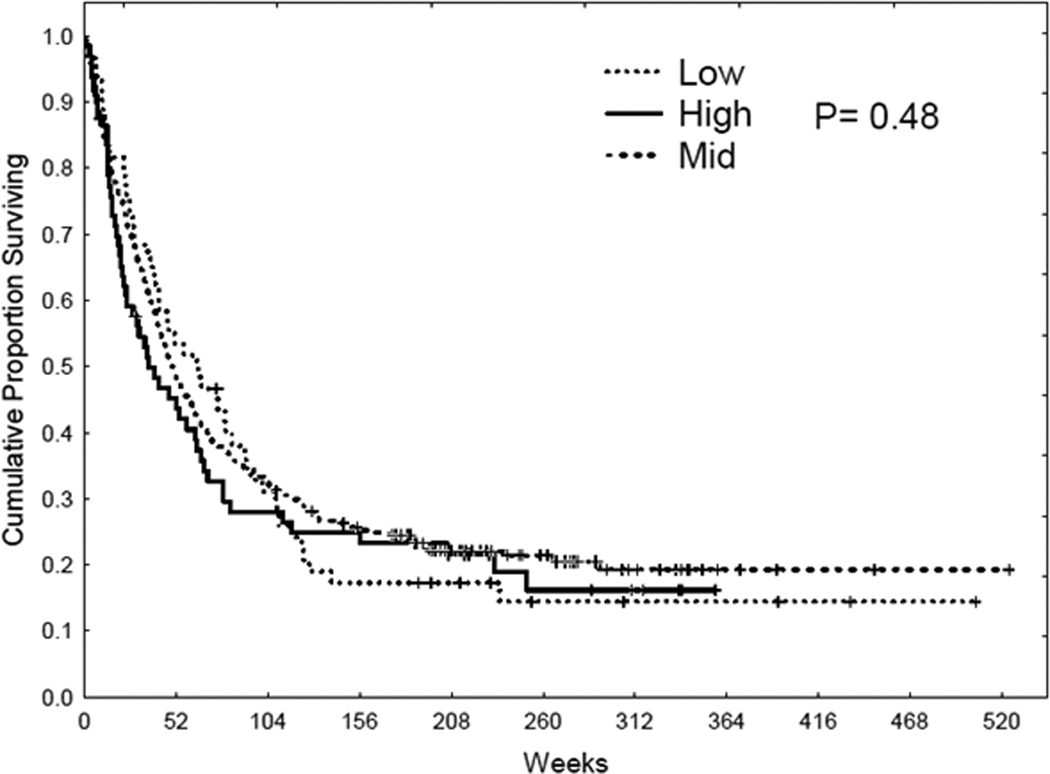

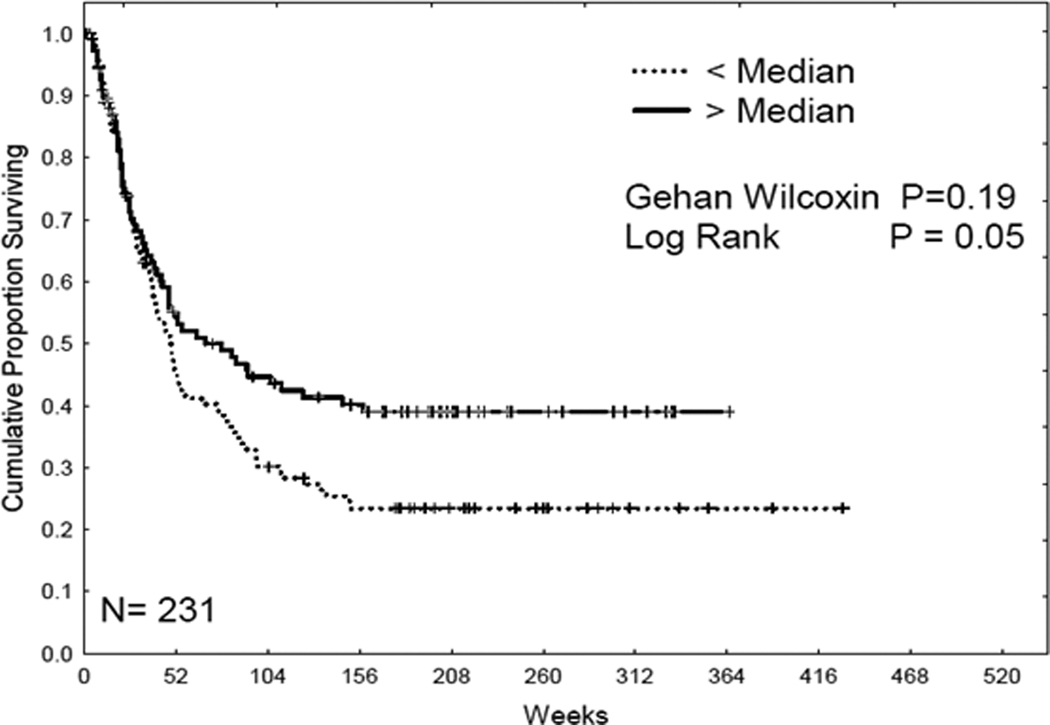

Low levels of B55α protein expression correlate with shorter CR duration in AML patients

415 AML patients from the total AML patient population (511 patients) were used to analyze overall survival. Patients were equally divided into 2 groups according to the protein level. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were derived to determine overall survival with different protein levels. As shown in Figure 6, there was no significant correlation with overall survival and protein expression. The effect of B55α expression level on remission duration was analyzed in the 231 patients that achieved complete remission (Figure 7). AML patients with lower levels of B55α exhibited significantly shorter CR duration than patients expressing high levels of the B subunit (logrank p = 0.05; Figure 7). That AML patients expressing low levels of B55α would have shorter periods of CR would be predicted based on the expectation that these patients would have active AKT.

Figure 6. B55 α levels do not correlate with overall survival.

Kaplan Meier curve for overall survival (OS) for the AML patient set (N = 256) based on expression of B55α.

Figure 7. B55 α levels are unfavorable for complete remission duration.

Kaplan Meier curve for complete remission (CR) duration for the AML patient set (N = 231) based on expression of B55α.

Discussion

The activation of numerous survival kinases in AML would suggest that PP2A is either dysregulated or inactivated. The study by Gallay and colleagues9 has suggested a link between AKT T308 phosphorylation, low PP2A levels activity, and poor patient outcome. However, the mechanism behind these associations is not clear. The role for PP2A as a tumor suppressor has been established in CML where BCR-ABL suppression of the protein phosphatase via the SET protein has been established27,28. A recent study has determined that a SET binding protein (i.e. SETBP1) may similarly inactivate PP2A in AML29. In the present study, we see a link between expression of a specific PP2A B subunit (i.e. B55α) and dephosphorylation of AKT at T308. Consistent with activated AKT when B55α is suppressed, AML patients expressing low levels of B55α also exhibited higher levels of phosphorylated p70 S6 Kinase. The observation that there was increased phosphorylation of BAD at S136 with increased B55α expression was not expected. As noted earlier, there is a competition between PP2A B subunits where subunits that are not in active complexes are degraded18, 26. It is plausible that a B subunit other than B55α is responsible for dephosphorylation of BAD at serine 136 and that B subunit is suppressed when B55α is expressed. Of course such a model would assume that a kinase other than AKT is responsible for BAD serine 136 phosphorylation in the AML patients. Supporting this possibility, a recent paper has indicated that various PKC isoforms can phosphorylate BAD at serine 13630.

While the particular AKT targets that may be necessary for the promotion of leukemogensis and drug resistance are still not clear, it is becoming evident that an optimal level of AKT kinase activation may be required for proper function of cellular processes. For example, chemotaxis of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) is regulated in part by Stromal Cell Derived Factor 1 (SDF-1) induced PP2A association with AKT31. In the study by Basu and colleagues31, inhibition of PP2A by okadaic acid (OA) or siRNA against the PP2A catalytic suppresses chemotaxis in HSC. The requirement for an optimal level of AKT activation in SDF-1 mediated homing is evident by experiments that show that a PI3K/AKT inhibitor (i.e. LY29400) restores chemotaxis in OA treated cells while LY29400 alone actually inhibits chemotaxis. It is reasonable to speculate that modulation of AKT activity in AML blast cells by PP2A will likewise be important.

The identification of B55α as an AKT regulator in AML provides a new possible biomarker for AML. Expression of B55α protein in blast cells from AML patients was much lower than in counterpart cells from normal donors. The reduced levels of the B subunit in the leukemia cells suggest that B55α may play a tumor suppressor role in AML. While B55α was not prognostic for overall survival, expression of lower levels of the protein appears to be unfavorable for longer CR duration. This finding suggests that B55α plays an important role in AML biology by regulating AKT. Promoting PP2A activity mediated by B55 α in AML leukemia cells would be useful as a means to reverse the high levels of AKT in leukemic cells with restoration of sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs. Possible means to achieve this goal might involve targeting PP2A inhibitors such as SET or to suppress expression of PP2A subunits that might compete with B55 α. In conclusion, strategies to promote B55 α inactivation of AKT may be useful for the therapy of AML.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Pankil Shah for work on statistical analysis.

This work was supported by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (grant 6089) and the National Institutes of Health (PO1 grant CA-55164).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Martelli AM, Evangelisti C, Chiarini F, McCubrey JA. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mTOR signaling network as a therapeutic target in acute myelogenous leukemia patients. Oncotarget. 2010;1:89–103. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fathi AT, Grant S, Karp JE. Exploiting cellular pathways to develop new treatment strategies for AML. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samudio I, Konopleva M, Carter B, Andreeff M. Apoptosis in leukemias: regulation and therapeutic targeting. Cancer Treat Res. 2010;145:197–217. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69259-3_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martelli AM, Evangelisti C, Chiarini F, Grimaldi C, Manzoli L, McCubrey JA. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling network in acute myelogenous leukemia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:1333–1349. doi: 10.1517/14728220903136775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martelli AM, Nyåkern M, Tabellini G, Bortul R, Tazzari PL, Evangelisti C, Cocco L. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway and its therapeutical implications for human acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:911–928. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholl C, Gilliland DG, Fröhling S. Deregulation of signaling pathways in acute myeloid leukemia. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:336–345. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornblau SM, Tibes R, Qiu YH, Chen W, Kantarjian HM, Andreeff M, Coombes KR, Mills GB. Functional proteomic profiling of AML predicts response and survival. Blood. 2009;113:154–164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornblau SM, Womble M, Qiu YH, Jackson CE, Chen W, Konopleva M, Estey EH, Andreeff M. Simultaneous activation of multiple signal transduction pathways confers poor prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:2358–2365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallay N, Dos Santos C, Cuzin L, Bousquet M, Simmonet Gouy V, Chaussade C, Attal M, Payrastre B, Demur C, Récher C. The level of AKT phosphorylation on threonine 308 but not on serine 473 is associated with high-risk cytogenetics and predicts poor overall survival in acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:1029–1038. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millward TA, Zolnierowicz S, Hemmings BA. Regulation of protein kinase cascades by protein phosphatase 2A. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:186–191. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao Y, Hung MC. Physiological regulation of Akt activity and stability. Am J Transl Res. 2010;2:19–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo YC, Huang KY, Yang CH, Yang YS, Lee WY, Chiang CW. Regulation of phosphorylation of Thr-308 of Akt, cell proliferation, and survival by the B55alpha regulatory subunit targeting of the protein phosphatase 2A holoenzyme to Akt. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1882–1892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen W, Possemato R, Campbell KT, Plattner CA, Pallas DC, Hahn WC. Identification of specific PP2A complexes involved in human cell transformation. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen W, Arroyo JD, Timmons JC, Possemato R, Hahn WC. Cancer-associated PP2A Aalpha subunits induce functional haploinsufficiency and tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8183–8192. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCright B, Virshup DM. Identification of a new family of protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26123–26128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssens V, Longin S, Goris J. PP2A holoenzyme assembly: in cauda venenum (the sting is in the tail) Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strack S, Cribbs JT, Gomez L. Critical role for protein phosphatase 2A heterotrimers in mammalian cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47732–47739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eichhorn PJ, Creyghton MP, Bernards R. Protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunits and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1795:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sontag E, Nunbhakdi-Craig V, Bloom GS, Mumby MC. A novel pool of protein phosphatase 2A is associated with microtubules and is regulated during the cell cycle. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1131–1144. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCright B, Rivers AM, Audlin S, Virshup DM. The B56 family of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) regulatory subunits encodes differentiation-induced phosphoproteins that target PP2A to both nucleus and cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22081–22089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruvolo PP, Clark W, Mumby M, Gao F, May WS. A functional role for the B56 alpha subunit of protein phosphatase 2A in ceramide-mediated regulation of Bcl2 phosphorylation status and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:22847–22852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kornblau SM, Singh N, Qiu Y, Chen W, Zhang N, Coombes KR. Highly phosphorylated FOXO3A is an adverse prognostic factor in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1865–1874. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu J, He X, Baggerly KA, Coombes KR, Hennessy BT, Mills GB. Non-parametric quantification of protein lysate arrays. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1986–1994. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neeley ES, Kornblau SM, Coombes KR, Baggerly KA. Variable slope normalization of reverse phase protein arrays. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1384–1389. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Scuderi A, Letsou A, Virshup DM. B56-associated protein phosphatase 2A is required for survival and protects from apoptosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3674–3684. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3674-3684.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perrotti D, Neviani P. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), a drugable tumor suppressor in Ph1(+) leukemias. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:159–168. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neviani P, Santhanam R, Trotta R, Notari M, Blaser BW, Liu S, Mao H, Chang JS, Galietta A, Uttam A, Roy DC, Valtieri M, Bruner-Klisovic R, Caligiuri MA, Bloomfield CD, Marcucci G, Perrotti D. The tumor suppressor PP2A is functionally inactivated in blast crisis CML through the inhibitory activity of the BCR/ABL-regulated SET protein. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cristóbal I, Blanco FJ, Garcia-Orti L, Marcotegui N, Vicente C, Rifon J, Novo FJ, Bandres E, Calasanz MJ, Bernabeu C, Odero MD. SETBP1 overexpression is a novel leukemogenic mechanism that predicts adverse outcome in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:615–625. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thimmaiah KN, Easton JB, Houghton PJ. Protection from rapamycin-induced apoptosis by insulin-like growth factor-I is partially dependent on protein kinase C signaling. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2000–2009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basu S, Ray NT, Atkinson SJ, Broxmeyer HE. Protein phosphatase 2A plays an important role in stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXC chemokine ligand 12-mediated migration and adhesion of CD34+ cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:3075–3085. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]