Abstract

Influenza vaccines are less effective in older people than younger people. This impaired ability to protect older people from influenza viral lung infection has important implications as older people suffer a higher morbidity and mortality from influenza viral lung infection than younger people. Therefore, the development of novel effective vaccines that induce protection from influenza viral infections in older people are urgently needed. We had previously shown that direct linking the TLR5 activator, flagellin, to viral peptides induces effective immunity to viral antigens in young mice and people, respectively. In this study, we tested the efficacy of this vaccine platform with the hemagglutinin peptide of the influenza A strain virus (vaccine denoted as STF2.HA1-2) in protecting aged mice from subsequent influenza viral lung infection. We found that a 3.0μg dose of the vaccine was effective in reducing mortality and increasing clinical well-being during influenza viral lung infection in aged mice. However, this effect was inferior to the response induced in young mice. Defects in the adaptive immune system but not the innate immune system were associated with this reduced effectiveness of the vaccine with aging. Our results indicate that the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine is effective in protecting aged hosts from influenza lung infection, although defects in the adaptive immune system with aging may limit the effectiveness of this vaccine in older people.

Keywords: Ageing, influenza viral infection

Introduction

Within the next forty years the number of older people in the world will exceed the number of young people for the first time in history. As the number of older people grows, their health care needs will pose an ever-increasing burden on our health system. Altered immune responses in older people are responsible for many diseases, as well as for increased morbidity and mortality to infections and cancer. For example, influenza viral lung infections are a growing public health concern in the elderly because of their predisposition for secondary bacterial pneumonia and their ability to exacerbate chronic heart and lung diseases [1]. These infections not only induce higher morbidity and mortality in older than younger people [2], but are also increasing in number, as demonstrated in a study reporting a 20% increase in hospitalization rates for community acquired pneumonia from 1988 to 2002 for patients aged 65 to 84 years [3].

Vaccines to protect older people from influenza viral infection have only been partially successful. Currently, the trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine reduces hospital rates for pneumonia by 48-57% and mortality by 36-54% in community dwelling older people [4, 5]. However, these vaccines fail to provide as high a level of immune protection for older people as for younger people, who typically respond to influenza viral infection with greater than 90% efficacy [5, 6]. Parallel to the increased susceptibility to microbial infection and cancer in older people, reduced efficacy of vaccines are likely caused by age-induced alterations in the immune system.

Most studies on aging and immune function have focused on adaptive T cell responses, with several reports showing that aging impairs T cell IL-2, IFN-γ production, and Th1 immunity [7-9], one of the critical immune defenses to infection from intracellular pathogens such as viruses. Aging also impairs T-cell CD28 surface upregulation [10] and immune synapse formation [11]. Furthermore, aging reduces T cell thymic output, leading to reduced numbers of naïve T cells. In addition, aging leads to an accumulation of memory T cells [12], which exhibit defective CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cell function [13, 14]. Other components of the adaptive immune system, including antibody formation by B cells, may also be impaired with aging [15, 16].

The innate immune system acts as the first line of defense against pathogen invasion [17]. Studies over the last ten years have determined that activation of the innate system, in particular through the Toll like receptors (TLRs), can lead to the maturation of dendritic cells (DCs), which subsequently stimulate T cell responses and initiate adaptive immunity [17, 18]. Less is known about the role of aging on innate immunity. Some studies in this area have found no alteration in the innate system with aging [9] but other studies have documented that cytokine responses are elevated in aged human DCs [19] and there is experimental data indicating that responses to TLR activation decline with aging [20].

We had previously reported on a novel vaccine platform in which an innate activator, flagellin, which stimulates TLR5, is linked to nominal antigens or viral peptides [21-23]. We have shown that this vaccine induces both an effective humoral and cellular immune response that protects young hosts from West Nile and influenza viral infection. In these studies, we demonstrated that flagellin must be directly linked to the immunizing peptides to induce protective immunity [22, 23]. However, in all of these studies young mice were employed. Importantly, we recently reported the effectiveness of this vaccine in inducing productive anti-influenza immune responses in healthy young adults [24].

Given the increased morbidity and mortality from influenza viral infections in older people, effective vaccine strategies to protect older people from influenza viral infection are urgently needed. In this study, we tested the efficacy of our flagellin vaccine platform to induce protective immunity to influenza viral infection in aged mice. Our study determined that a 3μg dose of the vaccine was effective in increasing survival and improving clinical outcome in response to influenza viral infection in aged mice. Yet this response was inferior to that induced in young mice. A lower 0.3μg dose of vaccine was effective in inducing humoral immunity to the viral epitopes and protection from subsequent influenza viral infection in young hosts however, aged mice exhibited an inferior humoral response and were not protected from subsequent influenza viral infection when immunized with the lower dose of vaccine. Defective adaptive immunity, but preserved innate immune responses to the vaccine were associated with the reduced efficacy of the vaccine in aged mice. Our study indicates that a 3.0μg STF2.HA1-2 vaccine is effective in aged mice to protect from influenza viral infection, although defects in the adaptive immune system with aging may limit the effectiveness of this vaccine in older people.

Materials and Methods

Vaccine design

STF2 (flagellin from Salmonella typhimurium type 2) was genetically fused to the globular head domain (HA1-2) of the A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) influenza virus hemagglutinin (denoted as STF2.HA1-2). The HA1-2 moiety of the vaccine is a 223 amino acid subunit of the HA1 polypeptide. It spans the substrate binding domain and contains most of the HA neutralizing antibody epitopes. The design of the HA1-2 subunit is described in detail in our prior work [25]. For generation of the HA1-2 flagellin fusion, the codon optimized synthetic HA1-2 subunit of the hemagglutinin (HA) globular head domain of PR8 was fused to the C-terminus of the full-length sequence of Salmonella typhimurium fljB (flagellin phase 2), STF2 (DNA2.0 Inc., Menlo Park, CA) to form STF2.HA1-2. STF2.HA1-2 was cloned into the pET24a vector and protein was expressed in BLR3 (DE3) cells (Novagen, San Diego, CA; Cat). High expressing clones were cultured overnight and used to inoculate fresh LB medium supplemented with 25 mg/ml kanamycin, 12.5 mg/ml tetracycline and 0.5% glucose. At an OD600 = 0.6, protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (8,000g for 7 minutes) and disrupted. Inclusion bodies were washed and dissolved in 8M urea, and the protein was recovered by cation exchange. Protein refolding was achieved by rapid dilution and further purified by anion exchange (Source Q, GE/Amersham). For final polishing and endotoxin removal, a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (10/300 GL, GE/Amersham) was used. Endotoxin contamination was assayed by using standard Chromogenic Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) as directed by the manufacturer.

Mice, immunization protocol and viral infection

Aged (15-18 months of aged) and young (2-4 months of aged) BALB/c mice were obtained from the NIA rodent facility. STF2.HA1-2 was given subcutaneously at either 0.3 or 3μg in 100μl volume per mouse. Mice received this on day +0 and then a boost at day +14. On day +21, mice were bled to obtain sera for assessment of humoral immune response to the vaccine. Mice were challenged with influenza viral infection (PR8) via intra-nasal (i.n) infection on day +28 after initial 1st dose of STF2.HA1-2 with an LD90 dose of the virus (8000 egg infectious units, EID). Mice were then observed up to 21 days for survival and clinical presentation. Clinical score were assigned as follows: 0: normal, 1: slightly ruffled fur, 2: ruffled fur, 3: ruffled fur and inactive, 4: hunched/moribund, 5: dead, as previously reported [26]. Use of mice in this study was approved by the Yale University IACUC.

Serum antibody measurement

Sera were harvested at day +21 post initial vaccination (i.e., 7 days after the boost dose) and IgG levels were determined by ELISA as previously reported [23].

MDCK whole cell ELISA

Sera were tested for reactivity with influenza A infected MDCK cells as previously reported [23]. Briefly, MDCK cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured with DMEM medium until cells were confluent. Cells were then incubated with 1 ×106 EID of PR8 influenza virus. After 60 min incubation at 37°C, 200ul DMEM media was added and the cells were incubated over night. Then the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 10% formalin at RT for 10 mins. After another three washes, the cells were incubated with ADB for 1h at RT. Serial dilutions of the sera were added to the cells for 1-2h incubation time. Cells were subsequently washed and then cultured with HRP-coated anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunochemical, West Grove, PA) for 30 mins at RT followed by TMB ultra substrate solution (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The reaction was subsequently stopped by adding 25ul of 1NH2S04 and the optical density at 450 NM was measured. Data reflect the mean Δ O.D. (infected-uninfected cells) of triplicate wells / sample.

Viral neutralization assay

MDCK cells were plated in 96 well plates in DMEM 10% FBS and grown to 90% confluency. Sera, at indicated dilutions, were added to the wells in phenol red-free DMEM +0.1% BSA. An equal volume of PR8 virus at 1:1000 dilution in the same media was added to the wells. Wells containing medium only and virus only were included as controls. The plates were incubated for 30 mins at 37°C after which the MDCK monolayers were washed with PBS and then 100ul of serum: virus mixture was added to the wells at 37°C for 48h. After this period, media was aspirated and replaced with fresh media containing vital dye neutral red (Sigma). 2μl lysis, containing 9% Triton X, solution was then added. The MDCK cells were incubated for another h, after which neutral red dye was aspirated and the cells fixed in 1% formaldehyde / 1% CACL2 solution (Sigma) for 5 min at RT. The solution was aspirated and 100 μl / well extraction medium (50% ethanol / 1% acetic acid) was added and incubated for another 20 min at RT. The amount of dye released was measured by absorbance at 540nm wavelength. Cell death, which is the equivalent of viral infectivity, was measured as a decrease in the amount of dye released as compared to control. % lysis of each serum dilution was calculated as:

where sample, max and med refer to absorbance values in wells representing experimental samples, maximum lysis, and medium only, respectively.

ELISPOT assay

BALB/c mice were immunized with 3.0μg of the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine as described above and spleens were harvested on day +21. Spleen cells were incubated at 1×107/ml with HA (PR8) protein at 2μg/ml in 96 well ELISPOT plates. After 18h incubation, the plate was washed at 37°C, and further incubated with biotin-conjugated detection antibody for 2h at RT. The plate was then washed and incubated with strepavidin-AP for 1h. The plate was then washed again and incubated with BCIP/NBT substrate for 5 min. All ELISPOT reagents were purchased from BD Biosciences. Spots were read on an automated ELISPOT reader (CTL, Cleveland, OH).

Cytokine ELISA

ELISA for IL-6 and TNF-α in the serum post STF2.HA1-2 administration or in culture supernatants were measured using kits from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA).

DC culture and flow cytometry

Bone marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were cultured as previously reported [27]. Splenic DCs were enriched using kits from EasySep (Vancouver, CA). DCs were stimulated with the indicated dose of flagellin (from Salmonella typhimurium, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) or PBS control, or the indicated dose of STF2.HA1-2 or HA1-2 lacking flagellin for indicated time points and supernatants were harvested for cytokine analysis, described above. Also, DCs were stained with fluorescently tagged monoclonal antibodies (eBiosciences) and surface upregulation of indicated costimulatory molecules was acquired on a FACscalibur flow cytometer and analyzed via flowjo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

TLR PCR assay

Young BALB/c mice were injected s.c., with 1 μg of the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine, flagellin-only positive control STF2 or the negative control HA1-2 lacking flagellin. Aged BALB/c mice were injected s.c., with 1 μg of the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine. At 3h post immunization, spleens were harvested from each age group and flash frozen in a dry ice ETOH bath and transported on dry ice. Frozen spleens were stored at -70°C until use. For each group, DNase-treated RNA was isolated from the spleens using Trizol suspension with the Purelink RNA mini kit (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA). RNA samples were run on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel to ensure the presence of the 28s and 18s RNA bands that are indicative of the absence of RNA degradation. Absorbance 260 of the RNA samples was used to calculate RNA yields and 5 μg of each RNA sample were reverse-transcribed to first strand cDNA with reagents from SABiosciences (Frederic, MD). All the resulting cDNA was mixed with a SYBR green-containing PCR master mix (SABiosciences Corporation) and distributed to all 96 wells of a TLR array (SABiosciences). The plate was run on an Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA) 7300 Real-Time PCR instrument using one denaturation cycle at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 15s / 95°C denaturation and 1 min / 60°C annealing and extensions. Data was collected during the 60°C stage at each cycle. A default dissociation curve cycle was run at the end of the PCR reaction to ensure a single peak for the PCR products. Amplification curves for all groups were analyzed using the same threshold (Ct) and background start and stop cycles to enable inter-group comparisons. Transcriptional levels of genes in response to each vaccine type were calculated relative to unimmunized control mice within each age group using the ΔΔCt comparative quantification method on the SABiosciences Corporation's web portal.

Statistical analysis

Survival between groups was evaluated via the Logrank method. Repeated values were assessed by ANOVA. All statistics were calculated on Graphpad prism software, significance was denoted with a p<0.05.

Results

High dose STF2.HA1-2 confers protection to aged mice from subsequent influenza viral infection although this response is inferior to the response noted in young mice

Our prior work has established that flagellin (denoted as STF2) must be directly linked to the viral antigen to induce protection from subsequent viral infection [22, 23]. In support of this, only the directly linked vaccine induced the production of serum anti-HA antibodies, whereas neither STF2 nor the globular head of HA (denoted as HA1-2) of the PR8 influenza A virus induced the generation of anti-HA specific antibodies (Supplemental Figure 1).

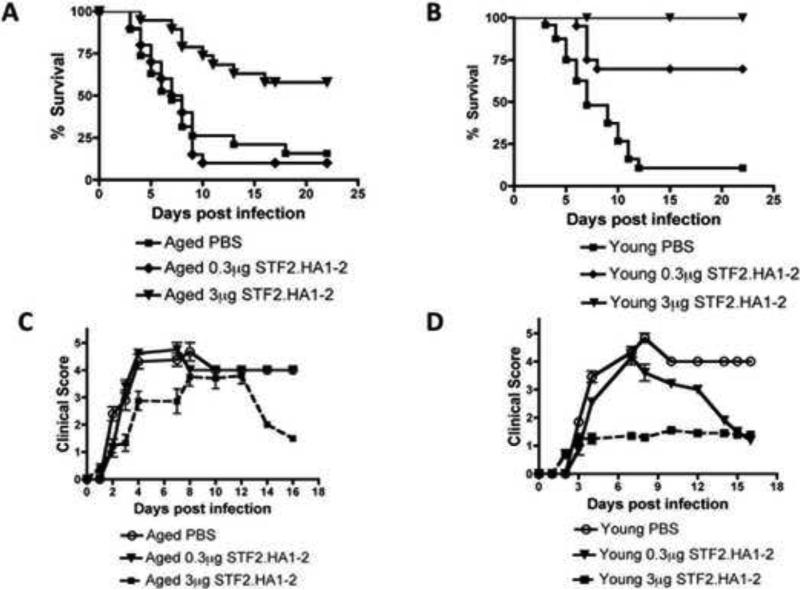

We next examined the efficacy of the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine platform to induce protection from subsequent influenza viral infection in aged mice. We used two doses of the vaccine (0.3 and 3μg) and administered it to young and aged BALB/c mice. Two weeks after the second administration of the vaccine (i.e., boost), the mice were challenged intranasally (i.n) with PR8 strain influenza A virus. In the aged mice, the 3μg dose significantly improved survival and additionally improved clinically well being after infection (Figure 1A + C).

Figure 1. Effectiveness of STF2.HA1-2 vaccine to protect aged mice from subsequent influenza viral infection.

A: BALB/c aged mice were vaccinated with the 3μg or 0.3μg dose of STF2.HA1-2 vaccine according to protocol described in material and methods or PBS control and then i.n. challenged with influenza virus 1 week later. Mortality was recorded. Mice that received 3μg STF2.HA1-2 vaccine exhibited a significant extension of survival vs. the other groups (p<0.01, Logrank). N = 20 mice / group B: BALB/c young mice were vaccinated with the 3μg or 0.3μg dose of STF2.HA1-2 vaccine or PBS control and then challenged with influenza virus via i.n., injection 1 week later. Mortality was recorded. Mice that received either dose of STF2.HA1-2 exhibited a significant extension of survival vs. PBS control (p<0.01, Logrank). N = 20 mice / group C-D: Clinical score was recorded for vaccinated and control groups shown in A and B. Only the 3μg STF2.HA1-2 aged group exhibited an improved clinical status, whereas in young mice both vaccinated groups exhibited an improved clinical status although the 0.3μg STF2.HA1-2 group initially was sick and then recovered. N = 20 mice / group

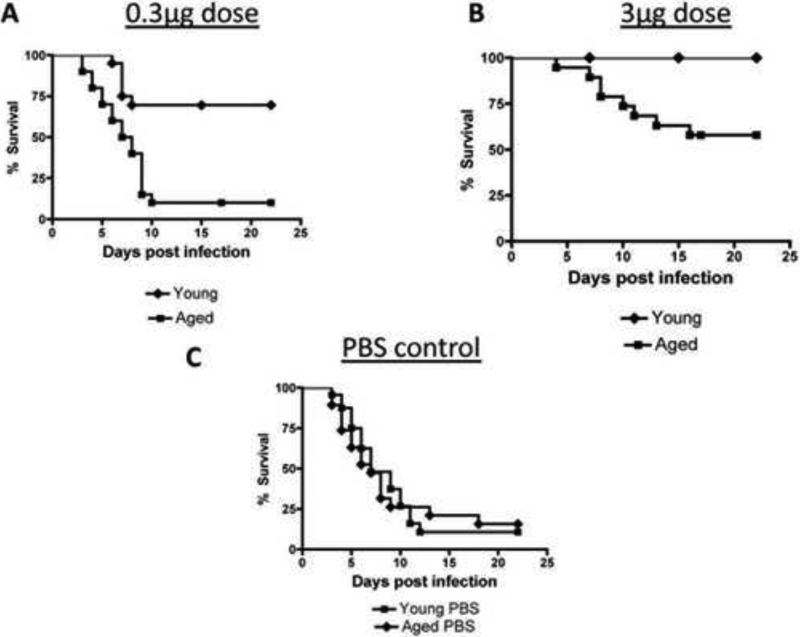

However, the 0.3μg failed to protect aged mice from influenza viral infection and did not improve clinical status after infection (Figure 1A + C). In young mice, both doses were effective in protecting mice from infection and improving clinical status (Figure 1B + D). Among mice that were immunized, young mice exhibited a superior survival at both doses than aged mice (Figure 2A-B). Young and aged mice that were not vaccinated but received PBS control exhibited a similar mortality rate after infection with influenza virus (Figure 2C). Thus, the 3μg dose, but not the lower dose, of the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine confers protection to aged mice to subsequent influenza viral infection.

Figure 2. STF2.HA1-2 vaccine is more effective in protecting from subsequent influenza viral infection in young mice than in aged mice.

A-B: At either 0.3 or 3μg dose of vaccine, young mice exhibited a significantly improved survival vs. aged vaccinated mice. Differences in each plot were significant (p<0.01, Logrank). N = 20 mice / group.

C: Aged and young mice were treated with PBS control in place of STF2.HA1-2 vaccine and were then challenged with influenza virus two weeks after control boost. Survival was recorded. There was no significant difference between the groups. N = 20 / group

The raw data from this Figure is the same as shown in Figures 1A and B.

Aged mice exhibit impaired humoral response to STF2.HA1-2 compared to young mice

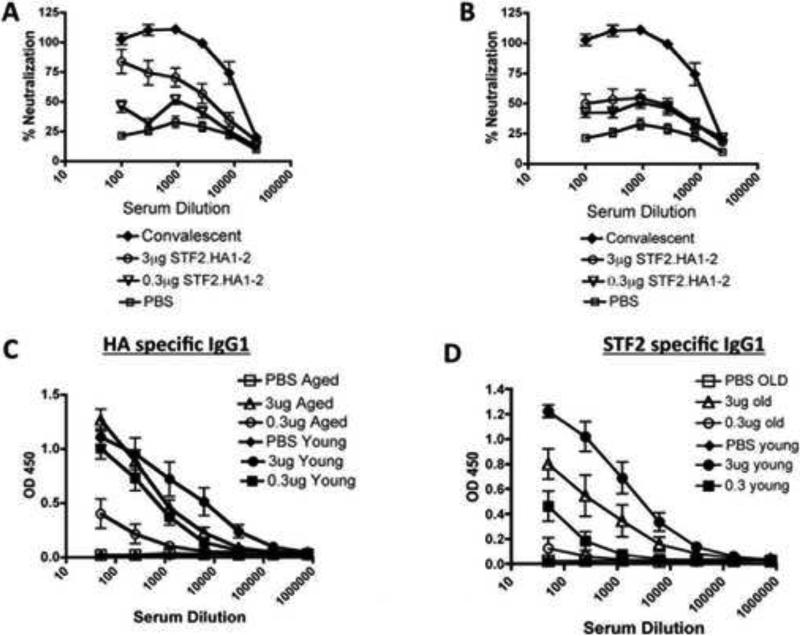

As neutralizing antibodies are critical for protection from influenza viral infection, we next measured the humoral response of young and aged mice administered the vaccine. One week after mice were administered the boost of STF2.HA1-2, sera were harvested and its ability to neutralize live virus in culture was measured. The sera from young mice that were administered the 3μg dose of the vaccine exhibited effective viral neutralization, and the lower dose was still able to induce neutralization although to a lesser degree (Figure 3A). Sera from aged mice administered the 0.3 or 3μg vaccine dose exhibited enhanced viral neutralization compared to controls (Figure 3B) but the aged mice that were immunized with the higher dose did not reach the level of neutralization obtained in young counterparts (Figure 3 A-B).

Figure 3. Aged vaccinated mice exhibit a reduced humoral response to the vaccine than young vaccinated mice.

A-B: Sera from young (A) or aged (B) vaccinated mice were added to viral growth cultures along with sera from mice that received PBS or from mice that previously cleared influenza virus (denoted as convalescent). Proportion of virally infected cells that were killed was then measured. Results are representative of one experiment that was repeated with consistent results. N = 10 animals / group / experiment. Error bars = SEM

C: Sera from vaccinated mice and those that received PBS control were assayed for anti-HA IgG levels by ELISA. Differences within age groups between PBS and vaccinated groups were significant (p<0.001, ANOVA). Differences between young and aged at 0.3μg dose were significant (p<0.001, ANOVA).

D: Sera from vaccinated mice and those that received PBS control were assayed for anti-STF2 (flagellin) IgG levels by ELISA. Differences within young group between PBS and vaccinated groups were significant (p<0.001, ANOVA). In the aged group, the differences between PBS and 3μg dose were significant (p<0.001, ANOVA). Differences between young and aged at both doses were significant (p<0.001, ANOVA).

For C + D, results are representative of one experiment that was repeated with consistent results. N = 10 animals / group / experiment. Error bars = SEM

Young vaccinated mice exhibited increased serum levels of anti-HA1-2 IgG antibodies as compared to PBS treated controls (Figure 3C). Aged mice vaccinated with the 3μg vaccine were able to produce high titers antibodies, but the aged mice that received the 0.3μg of the vaccine exhibited lower titers of anti-HA1-2 antibodies than young counterparts, although the response in aged mice were greater than the response of aged mice treated with control (Figure 3C). Similar results were noted in the serum levels of anti-STF2 (i.e., flagellin) antibodies in young and aged mice, indicating that aged mice generated a reduced humoral response to both components of the vaccine than young mice. Hence, these results indicate that aged mice were able to induce a humoral response to the vaccine although this was inferior to the response generated in young mice.

We next determined if the antibodies induced by the vaccine recognized influenza infected viral cells. Hence, sera from young or aged mice were added to cultures of MDCK cells that were infected with PR8 influenza virus. Sera from young immunized mice exhibited higher binding to influenza-infected cells at both doses than aged vaccinated mice (Figure 4). In sum, these results demonstrate that the antibodies induced by the vaccine recognized virally infected cells and that this response was higher in young than aged mice.

Figure 4. Recognition of influenza infected cells by the sera of young and aged vaccinated mice.

Aged or young vaccinated mice were immunized with 3μg or 0.3μg dose of STF2.HA1-2 vaccine or PBS control and sera obtained 1 week after 2nd boost dose. Sera were then tested for reactivity to influenza infected MDCK cells in vitro. N = 10 animals / group / experiment. Young mice that previously cleared influenza virus (denoted as convalescent) were employed as a positive control. Data is representative of 1 experiment repeated with consistent results. There was a significant difference between the response of young and age at both the 0.3μg dose and the 3.0μg dose (p<0.001, ANOVA). Error bars = SEM

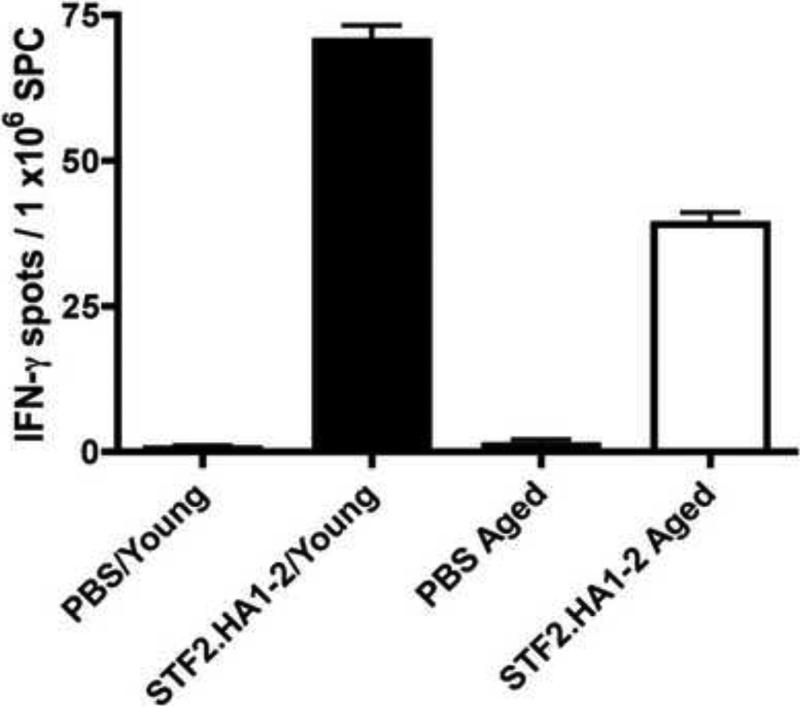

Aged mice exhibit defective cellular immune responses to STF2.HA1-2 than young mice

To assess cellular responses induced by the vaccine, spleen cells were harvested from young and aged mice one week after the boost with 3μg dose of the STF2.HA1-2 and IFN-γ (i.e., a Th1 cytokine) responses assessed by ELISPOT. Aged immunized mice exhibited an elevated response compared to aged mice treated with PBS control (Figure 5). However, this response was inferior to the IFN-γ response induced by the spleen cells harvested from young immunized mice. Hence, aged mice exhibited impaired cellular immune responses to the high dose of the vaccine than young mice.

Figure 5. Reduced cellular immune responses to STF2.HA1-2 vaccine in aged mice than young mice.

Young or aged BALB/c mice were administered the prime boost dose of 3.0μg of the vaccine subcutaneously. 1 week later, spleen cells were harvested and IFNγ producing spleen cell numbers were assessed by ELISPOT. N = 3 mice / group. Error bars represent SEM.

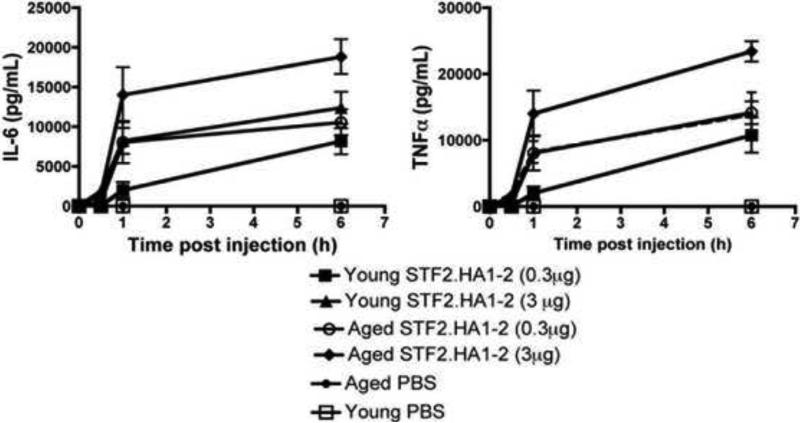

Aged mice exhibit preserved serum cytokine responses to STF2.HA1-2 vaccine

Since there are reports that certain TLR-induced inflammatory responses are reduced with aging [28], it is possible that an impaired innate response to flagellin could underlie the reduced effectiveness of the flagellin-based vaccine in aged mice. Upon TLR ligation a variety of cells secrete proinflammatory cytokines for example IL-6 and TNF-α within hours. We administered the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine subcutaneously and measured IL-6 and TNF-α in the serum up to 6h post injection. Sera from aged mice exhibited preserved serum cytokine responses to the vaccine compared to young mice (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Aged mice exhibit preserved innate cytokine responses within the serum in response to STF2.HA1-2 vaccine compared to young vaccinated mice.

Young or aged BALB/c mice were administered the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine subcutaneously and IL-6 and TNF-α was measured in the serum up to 6h post administration. Pooled data from two independent experiments, with n = at least 4 mice / group / experiment. Error bars represent SEM.

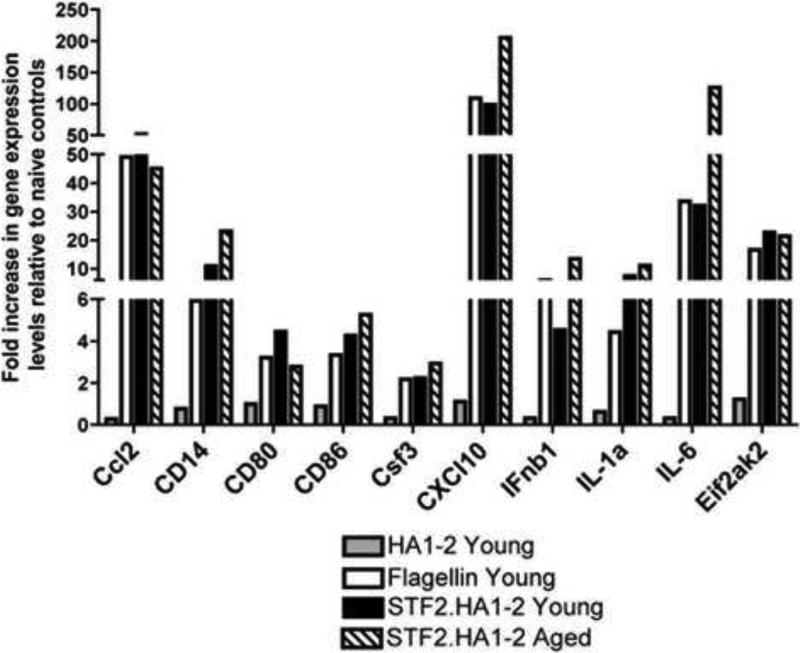

We next injected the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine, HA1-2 vaccine lacking flagellin (as a -ve control) and flagellin alone into young mice and harvested the mRNA from the spleens 3h post injection. The mRNA expression panel of young mice injected with the flagellin control showed the activation of a panel of genes specific to the TLR signal transduction pathway (Figure 7). These genes include members of the NF-κB pathway (e.g., IL-6, IL-1α Ifnβ-1, Ccl2, Csf3), chemokines (e.g.,C×CL10), adapters and TLR-interacting proteins such as CD14 as well as molecules involved in the regulation of adaptive immunity such as CD80 and CD86. The level of transcription relative to the non-injected, naive controls ranged from 2.2 fold to 200-fold depending on the gene. STF2.HA1-2 vaccine activated the transcription of these genes to a similar extent than young mice injected with flagellin alone, indicating that the TLR binding domains within the fusion vaccine remained intact and capable of stimulating a TLR-5 dependent innate immune response. The HA1-2 vaccine that lacked flagellin was unable to stimulate the transcription of these genes as expected (Figure 7). When the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine was injected into aged mice, the same panel of genes was transcribed to comparable extent as young mice implying that TLR signaling events within the spleen were intact with aging in this time frame (Figure 7).

Figure 7. TLR gene expression signaling pathways are similar in young and aged mice within the spleen after subcutaneous injection of STF2.HA1-2 vaccine.

Young and aged mice were injected with 1.0μg of vaccine and 3h post injection spleen cells were obtained and mRNA purified. In addition, young mice were injected with flagellin only or vaccine without flagellin (denoted as HA1-2). Gene expression was assessed by real time PCR using a TLR signal PCR array as detailed in the methods. N = 3 mice / group

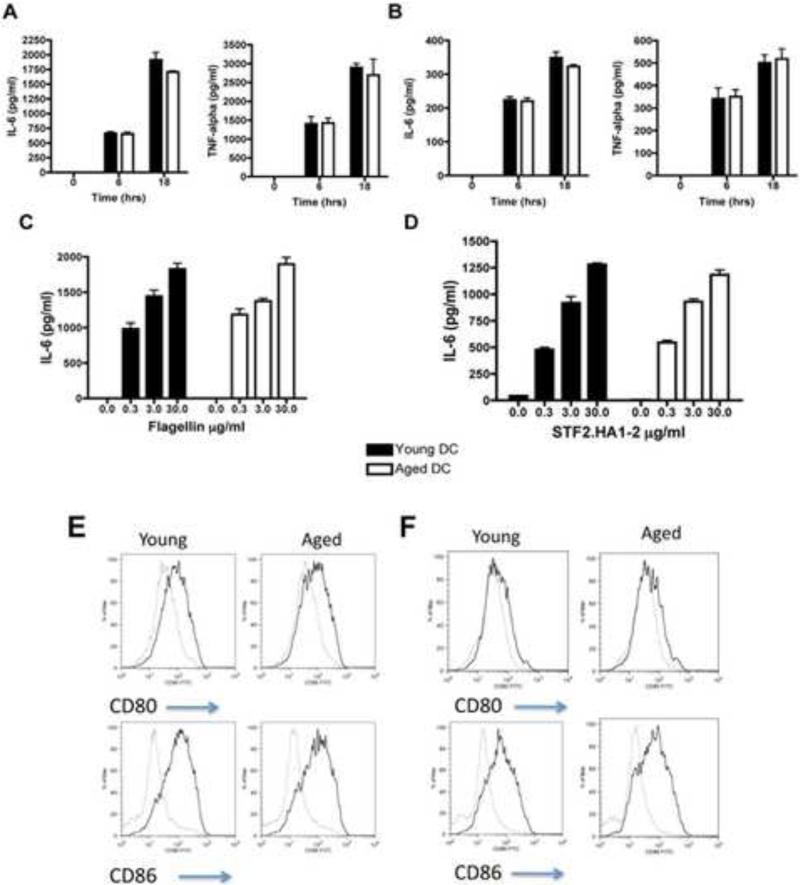

As TLR activation on conventional (myeloid) DCs is a key component to initiate specific adaptive immune responses [17], we next examined responses of conventional DCs from young and aged mice after stimulation with flagellin. In addition, we activated young and aged DCs with STF2.HA1-2 or HA1-2 control. We found that the production of TNFα and IL-6 was similar in aged BMDC and splenic DCs than young DCs after flagellin activation (Figure 8A-C). Similar results were noted in young and aged DCs stimulated with STF2.HA1-2 (Figure 8D). We found that aged bone marrow derived DCs (BMDCs) from aged mice were equally able to upregulate costimulatory molecules with either flagellin activation or activation with STF2.HA1-2 as compared to young DCs (Figure 8EF). These results demonstrate that the upregulation of costimulatory molecules and production of IL-6 and TNF-α by conventional DCs induced by either flagellin or STF2.HA1-2 is preserved with aging.

Figure 8. Aged conventional DCs exhibit similar inflammatory responses to activation with flagellin than young DCs.

A: Aged BMDCs exhibit similar IL-6 and TNF-α responses to 1μg/ml of flagellin than young BMDCs at either 6h or 18h of stimulation. One representative experiment repeated once with similar results. There were no statistical differences found between the young and aged groups. N = 3 mice as a source of cells / group / experiment. Error bars = SEM

B: Aged splenic DCs exhibit similar IL-6 and TNF-α responses to 1μg/ml of flagellin than young splenic DCs at either 6h or 18h of stimulation. One representative experiment repeated once with similar results. N = 3 mice as a source of cells / group / experiment. There were no statistical differences found between the young and aged groups. Error bars = SEM

C: Aged BMDCs exhibit similar IL-6 responses to a dose range of flagellin than young BMDCs. Supernatants were taken after 6h stimulation and IL-6 measured by ELISA. N = 3 mice as a source of cells / group / experiment. Error bars = SEM

D: Aged BMDCs exhibit similar IL-6 responses to a dose range of STF2.HA1-2 than young BMDCs. Supernatants were taken after 6h stimulation and IL-6 measured by ELISA. Note, 30μg/ml of HA1-2 control elicited <150 pg/ml of IL-6 from either aged or young BMDCs. N = 3 mice as a source of cells / group / experiment. Error bars = SEM

E: Aged and young BMDCs were stimulated with 3μg/ml of flagellin and the upregulation of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 were assessed by flow cytometry. Grey line = unstimulated, black line = flagellin stimulated. Representative experiment that was repeated with n = 3 mice as a source of cells / group / experiment. Histogram plots are gated on CD11c+ cells.

F: Aged and young BMDCs were stimulated with 3μg/ml of STF2.HA1-2 (black line) of HA1-2 control (grey line) and the upregulation of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 were assessed by flow cytometry. N = 3 mice as a source of cells / group. Histogram plots are gated on CD11c+ cells.

Discussion

Older people exhibit reduced response rates to influenza viral vaccination as compared to younger people [5, 29-31]. Increased protection to influenza viral infection in older people will reduce the morbid consequences that occur after influenza viral infection in older people, such as secondary bacterial pneumonia and exacerbations of chronic cardiopulmonary conditions [32]. In this study, we evaluated a novel influenza vaccine platform that links a TLR5 activator, flagellin, to the influenza viral peptide, HA. We had previously shown that this vaccine was highly effective at reducing morbidity and mortality from influenza viral infection in young mice and we have demonstrated its efficacy in inducing an anti-influenza immune response in young people [23, 24].

The current study found that the high dose of the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine was effective in reducing mortality and increasing clinical well being from influenza lung infection in aged mice. Our prior work has determined that generation of serum neutralizing antibodies in young mice remain present at least up to eleven months after immunization [33]. Thus, it is possible that protective effects of the high dose vaccine in the aged mice may last up to several months after immunization, although this will requires future investigation. However, this response was inferior to that induced in young mice. Moreover, whereas the lower dose was effective in improving survival and clinical status in young mice, it did not induce a positive effect in preventing influenza-induced mortality in aged mice.

We found that the vaccine induced an inferior humoral and cellular immune response in aged mice than in young mice. Innate stimulation can activate certain components of adaptive immunity. Thus, defective innate activation could be a potential explanation of our observed results. However, we found preserved innate cytokine and signaling responses both within the sera and spleens of vaccinated aged mice as compared to young mice.

DCs are key innate immune cells that activate components of adaptive immunity [34]. This is accomplished by DCs upregulating costimulatory molecules and producing cytokines in response to innate activation, such as ligation of TLRs [17]. We examined how aged conventional DCs respond to flagellin or to the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine in vitro and found that the response induced by flagellin or STF2.HA1-2 in aged DCs was similar to the response produced by young DCs. This is in agreement with our prior work in which we examined a spectrum of TLR activators in aged and young DCs and found that TLR activation was preserved in conventional DCs [9]. Defects in TLR1/2 activation on monocytes have been noted in humans [28], and TLR 7 and 9 activation in plasmacytoid DCs is impaired in both mice and humans [28, 35]. It is not yet known how human aging impacts TLR5 activation. Overall, we find no experimental evidence that TLR5 activation via flagellin is impaired with aging. Thus, our study indicates that the inferior response of the STF2.HA1-2 vaccine was not likely due to impaired innate activation via TLR5.

Aging is known to intrinsically impair components of both the T and B cell compartment, which are critical effectors of adaptive immunity [36]. A prior experimental study has provided evidence that a cocktail of proinflammatory cytokines could recover CD4+ T cell responses with aging [37]. Based on such evidence, one may predict that TLR-induced inflammatory responses could augment immunity with aging. Our study indicates that the current vaccine platform and the doses administered were not able to completely overcome the intrinsic defects within the adaptive immune system to restore protection in aged mice to the same degree as induced in young mice.

We previously have studied the safety and immunogenicity of a seasonal influenza vaccine, VAX125, in young adults aged 18 to 49 [38]. Doses of 0.5, 1 and 2 μg induced reciprocal geometric mean HAI titers of 301, 554 and 718, respectively, with high seroconversion and seroprotection rates in this age group [38]. More recently, we found that VAX125 was also safe and highly immunogenic in elderly subjects age 65 and above [39]. The geometric mean HAI titer observed after a single 5.0 μg dose (226) was similar to that achieved with a 0.5 μg dose in younger adults (301), suggesting that it requires nearly a 10-fold increase in dose to obtain the same titer in the elderly. These higher doses of VAX125 were very well tolerated in the elderly [39]. Thus, while the innate immune stimulus did lead to a vaccine that was highly immunogenic in the elderly at relatively low doses of vaccine, similar to our results in the mouse model, we find that the aged require a higher dose than the young to achieve comparable immune responses.

A prior study has indicated that re-populating aged mice with young T cells could restore T cell immunity with aging [40]. Along these lines, therapies that either recover aged induced defects within adaptive immune cells or allow repopulation of “young” adaptive immune cells within aged hosts may offer a possible mechanism to improve vaccine responses with aging.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1 Direct linkage of STF2 with HA1.2 is required to induce anti-HA IgG.

Groups of young BALB/c mice were immunized on day 0 and +14 with either: i) PBS; ii) STF2; iii) HA1.2; iv) a mixture of STF2 and HA1.2 (not directly linked); v) directly linked STF2.HA1.2; and vi) HA1.2 + alum. On day +21, serum was harvested and antibodies to HA measured by ELISA as described in materials and methods. Only mice that received STF2.HA1-2 (i.e., the vaccine that has direct linking of STF2 with HA1-2) exhibited detectable levels of anti-HA antibodies in the serum. N = at least 3-6 mice / group, error bars = SEM

Highlights.

In this study, we employed a vaccine platform that directly links flagellin, a TLR5 activator, with the influenza viral epitope, hemagglutinin, to examine if this vaccine induces protective immunity from subsequent viral infection in aged mice.

Our results demonstrate that a high dose of vaccine was effective in aged mice, although the induced protection was inferior to that found in young mice.

Defects in adaptive immune system were associated with the reduced efficacy of the vaccine in aged mice.

Acknowledgements

Work supported by NIH grant AG028082 to DRG. DRG is also supported by an Established investigator award from the American Heart Association and NIA K02AG033049.

Abbreviations

- BMDC

bone marrow derived dendritic cell

- DC

dendritic cell

- TLR

toll like receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kaplan V, Angus DC. Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Critical Care Clinics. 2003;19(4):729–48. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(03)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorina Y, Kelly T, Lubitz J, Hines Z. Trends in Influenza and Pneumonia Among Older Persons in the United States. Aging Trends. 2008;8:1–11. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fry AM, Shay DK, Holman RC, Curns AT, Anderson LJ. Trends in Hospitalizations for Pneumonia Among Persons Aged 65 Years or Older in the United States, 1988-2002. JAMA. 2005 December 7;294(21):2712–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.21.2712. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichol KL, Margolis KL, Wuorenma J, Von Sternberg T. The Efficacy and Cost Effectiveness of Vaccination against Influenza among Elderly Persons Living in the Community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(12):778–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409223311206. 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross PA, Hermogenes AW, Sacks HS, Lau J, Levandowski RA. The Efficacy of Influenza Vaccine in Elderly Persons. Ann Int Med. 1995;123(7):518–27. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-7-199510010-00008. 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns EALL, L'Hommedieu G, Goodwin JS. Specific humoral immunity in the elderly: in vivo and in vitro response to vaccination. J Gerontol. 1993 Nov;48(6):B231–6. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.6.b231. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haynes L, Linton P-J, Eaton SM, Tonkonogy SL, Swain SL. Interleukin 2, but Not Other Common {gamma} Chain binding Cytokines, Can Reverse the Defect in Generation of CD4 Effector T Cells from Naive T Cells of Aged Mice. J Exp Med. 1999 October 4;190(7):1013–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.1013. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thoman ML, Weigle WO. Cell-mediated immunity in aged mice: an underlying lesion in IL 2 synthesis. J Immunol. 1982;128(5):2358–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesar BM, Walker WE, Unternaehrer J, Joshi NS, Chandele A, Haynes L, et al. Murine myeloid dendritic cell-dependent toll-like receptor immunity is preserved with aging. Aging Cell. 2006;5(6):473–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boucher N, Dufeu-Duchesne T, Vicaut E, Farge D, Effros RB, Schachter F. CD28 expression in T cell aging and human longevity. Exp Gerontol. 1998;33(3):267–82. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(97)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia GG, Miller RA. Single-Cell Analyses Reveal Two Defects in Peptide-Specific Activation of Naive T Cells from Aged Mice. J Immunol. 2001;166(5):3151–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linton P-J, Dorschkind K. Age related changes in lymphocyte development and function. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(2):133–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Fujii H, Kishimoto H, LeRoy E, Surh CD, Sprent J. Aging Leads to Disturbed Homeostasis of Memory Phenotype CD8+ Cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195(3):283–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Randall TD, Swain SL. CD4 T cell memory derived from young naive cells functions well into old age, but memory generated from aged naive cells functions poorly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(25):15053–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433717100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frasca D, Landin AM, Alvarez JP, Blackshear PJ, Riley RL, Blomberg BB. Tristetraprolin, a Negative Regulator of mRNA Stability, Is Increased in Old B Cells and Is Involved in the Degradation of E47 mRNA. J Immunol. 2007;179(2):918–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson KM, Owen K, Witte PL. Aging and developmental transitions in the B cell lineage. Int Immunol. 2002;14(11):1313–23. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(10):987–95. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen Recognition and Innate Immunity. Cell. 2006;124(4):783. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Cao J-N, Su H, Osann K, Gupta S. Altered Innate Immune Functioning of Dendritic Cells in Elderly Humans: A Role of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase-Signaling Pathway. J Immunol. 2007;178(11):6912–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renshaw M, Rockwell J, Engleman C, Gewirtz A, Katz J, Sambhara S. Cutting edge: impaired Toll-like receptor expression and function in aging. J Immunol. 2002;169(9):4697–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huleatt JW, Jacobs AR, Tang J, Desai P, Kopp EB, Huang Y, et al. Vaccination with recombinant fusion proteins incorporating Toll-like receptor ligands induces rapid cellular and humoral immunity. Vaccine. 2007;25(4):763–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonald WF, Huleatt JW, Foellmer HG, Hewitt D, Tang J, Desai P, et al. A West Nile Virus Recombinant Protein Vaccine That Coactivates Innate and Adaptive Immunity. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(11):1607–17. doi: 10.1086/517613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huleatt JW, Nakaar V, Desai P, Huang Y, Hewitt D, Jacobs A, et al. Potent immunogenicity and efficacy of a universal influenza vaccine candidate comprising a recombinant fusion protein linking influenza M2e to the TLR5 ligand flagellin. Vaccine. 2008;26(2):201–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talbot HK, Rock MT, Johnson C, Tussey L, Kavita U, Shanker A, et al. Immunopotentiation of Trivalent Influenza Vaccine When Given with VAX102, a Recombinant Influenza M2e Vaccine Fused to the TLR5 Ligand Flagellin. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e14442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song L, Nakaar V, Kavita U, Price A, Huleatt J, Tang J, et al. Efficacious Recombinant Influenza Vaccines Produced by High Yield Bacterial Expression: A Solution to Global Pandemic and Seasonal Needs. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5):e2257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell TJ, Dwyer DW, Morgan T, Hollenbaugh JA, Dutton RW. The immune system provides a strong response to even a low exposure to virus. Clin Immunol. 2006;119(1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen H, Tesar BM, Walker WE, Goldstein DR. Dual Signaling of MyD88 and TRIF Is Critical for Maximal TLR4-Induced Dendritic Cell Maturation. J Immunol. 2008 August 1;181(3):1849–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1849. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panda A, Qian F, Mohanty S, van Duin D, Newman FK, Zhang L, et al. Age-Associated Decrease in TLR Function in Primary Human Dendritic Cells Predicts Influenza Vaccine Response. J Immunol. 2010;184:2518–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shahid Z, Kleppinger A, Gentleman B, Falsey AR, McElhaney JE. Clinical and immunologic predictors of influenza illness among vaccinated older adults. Vaccine. 2010;28(38):6145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullooly JP, Bennett MD, Hornbrook MC, Barker WH, Williams WW, Patriarca PA, et al. Influenza vaccination programs for elderly persons: cost-effectiveness in a health maintenance organization. Ann Int Med. 1994;121(12):947–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webster RG. Immunity to influenza in the elderly. Vaccine. 2000;18(16):1686–9. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McElhaney JE, Effros RB. Immunosenescence: what does it mean to health outcomes in older adults? Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(4):418–24. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu G, Tarbet B, Song L, Reiserova L, Weaver B, Chen Y, et al. Immunogenicity and Efficacy of Flagellin-Fused Vaccine Candidates Targeting 2009 Pandemic H1N1 Influenza in Mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001 August 10th;106:255–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stout-Delgado HW, Yang X, Walker WE, Tesar BM, Goldstein DR. Aging Impairs IFN Regulatory Factor 7 Up-Regulation in Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells during TLR9 Activation. J Immunol. 2008;181(10):6747–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linton PJ, Li SP, Zhang Y, Bautista B, Huynh Q, Trinh T. Intrinsic versus environmental influences on T-cell responses in aging. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:207–19. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maue AC, Eaton SM, Lanthier PA, Sweet KB, Blumerman SL, Haynes L. Proinflammatory Adjuvants Enhance the Cognate Helper Activity of Aged CD4 T Cells. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):6129–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804226. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Treanor JJ, Taylor DN, Tussey L, Hay C, Nolan C, Fitzgerald T, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant hemagglutinin influenza-flagellin fusion vaccine (VAX125) in healthy young adults. Vaccine. 2010;28(52):8268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor DN, Treanor JJ, Strout C, Johnson C, Fitzgerald T, Kavita U, et al. Induction of a potent immune response in the elderly using the TLR-5 agonist, flagellin, with a recombinant hemagglutinin influenza-flagellin fusion vaccine (VAX125, STF2.HA1 SI). Vaccine. 2011;29(31):4897–902. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Randall TD, Swain SL. Newly generated CD4 T cells in aged animals do not exhibit age-related defects in response to antigen. J Exp Med. 2005 March 21;201(6):845–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041933. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1 Direct linkage of STF2 with HA1.2 is required to induce anti-HA IgG.

Groups of young BALB/c mice were immunized on day 0 and +14 with either: i) PBS; ii) STF2; iii) HA1.2; iv) a mixture of STF2 and HA1.2 (not directly linked); v) directly linked STF2.HA1.2; and vi) HA1.2 + alum. On day +21, serum was harvested and antibodies to HA measured by ELISA as described in materials and methods. Only mice that received STF2.HA1-2 (i.e., the vaccine that has direct linking of STF2 with HA1-2) exhibited detectable levels of anti-HA antibodies in the serum. N = at least 3-6 mice / group, error bars = SEM