Abstract

In this work, the nucleation and growth of InAs nanowires on patterned SiO2/Si(111) substrates is studied. It is found that the nanowire yield is strongly dependent on the size of the etched holes in the SiO2, where openings smaller than 180 nm lead to a substantial decrease in nucleation yield, while openings larger than promote nucleation of crystallites rather than nanowires. We propose that this is a result of indium particle formation prior to nanowire growth, where the size of the indium particles, under constant growth parameters, is strongly influenced by the size of the openings in the SiO2 film. Nanowires overgrowing the etched holes, eventually leading to a merging of neighboring nanowires, shed light into the growth mechanism.

Keywords: A1. Nanostructures, A3. Nanowire growth, A3. Metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy, B2. Semiconductor III–V materials

Highlights

► Position controlled self-seeded InAs nanowire growth on Si is studied. ► The influence of a SiO2 mask gives information on the growth mechanism. ► An optimum indium particle size range for nanowire nucleation exists. ► The In particle size depends on SiO2 layer opening size and process conditions.

1. Introduction

Today's micro and nanoelectronic industry is more or less entirely based on silicon, a material that offers single crystalline substrates with a very high purity at a low cost. In contrast to other semiconductor materials, such as indium and gallium needed for III–V compound semiconductors, there will never be any shortage of silicon as it is the second most abundant material in the earth crust. These facts have initiated intense research efforts in developing epitaxial growth of non-silicon semiconductors on silicon substrates, particularly for applications in areas such as lighting, photo-voltaics, and high-speed electronics [1–4]. In this respect, the recent use of nanowires for heteroepitaxial growth of III–V semiconductors on Si has attracted considerable attention since their small diameter allows for relaxation of part of the strain resulting from the lattice mismatch at the heterointerface. Even in an extreme case, such as in the case of direct growth of InAs on Si with a lattice mismatch of 11.5%, where a high density of defects can be expected, no line or planar defects running along the length of the nanowires have been reported [5]. In addition, the small nucleation area leads to single crystalline wires, guaranteeing that no anti-phase boundaries are created inside a wire. Already a short distance above the substrate, high quality InAs is available, which can be used for many different applications [6]. Several groups have shown InAs and GaAs nanowire growth on Si [5,7–14]. In this work, we attempted to further understand the growth mechanism leading to self-seeded particle-assisted InAs nanowire growth (i.e. nucleated by liquid Indium particles) on Si and in particular to control the position of the wires. Such a position controlled growth of nanowires is required to use the superior electronic and opto electronic properties of III–V materials [15–17] for devices in combination with Si substrates [18].

In the following, we will evaluate the influence of the SiO2 mask on nanowire growth. First, we investigate the influence of the opening diameter on nanowire nucleation and their size. The results are then compared to the influence of pre-depositing Indium prior to growth. Then, we study the influence of the growth time on nanowire length and diameter. Finally, some interesting features observed in merged nanowire morphology will be discussed.

2. Method

Lowly doped Si (111) wafers were thermally oxidized to a SiO2 thickness of 45–55 nm. After dicing the wafer into 9×9 or 5×5 mm2 pieces, these were spin coated with PMMA, baked and exposed using electron-beam lithography (EBL). The exposed PMMA layer was then developed leaving holes to the SiO2 layer. The pattern was then transferred on to the SiO2 layer by etching for 55 s using a 1:10 buffered HF solution. After this step the PMMA layer was removed by Remover 1165 (Rohm and Haas) at 65 °C, for . This was followed by 90 s O2 plasma cleaning and a 30 min ozone ashing to remove any remaining organic material from the Si surface. The processing of the pattern is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. During the oxygen treatment and the following storage time, the surface in the openings was covered again by a native SiO2 layer. This layer was removed prior to growth by an additional HF etch step. In this case, the samples were etched for 2–8 min using a weak, 0.46 mol% HF in H2O solution. To minimize the effect of oxidation, the samples were loaded into the H2-atmosphere of the epitaxy system as quickly as possible, typically within 7–10 min. After the samples were loaded into the reactor they were heated to 625 °C and annealed at this temperature for 10 min in an H2 atmosphere, after this the samples were cooled down to growth temperature of 540 or 550 °C under a H2 atmosphere. After the growth temperature was reached, usually both sources, trimethylindium (TMI) and AsH3, were introduced simultaneously. The TMI and AsH3 molar fractions were varied from 3.1×10−6 to 4.0×10−6 and from 2.8×10−4 to 1.5×10−3, respectively. The growth system (EpiQuip 502-RP) was operated at 100 mbar and uses a H2 carrier gas flow of 6000 ml/min. To stop growth the TMI supply was switched off and the samples were cooled under AsH3 supply, to prevent decomposition of the nanowires. The AsH3 supply was turned off when the temperature reached 300 °C and the samples were taken out of the reactor as soon as the temperature dropped below 100 °C.

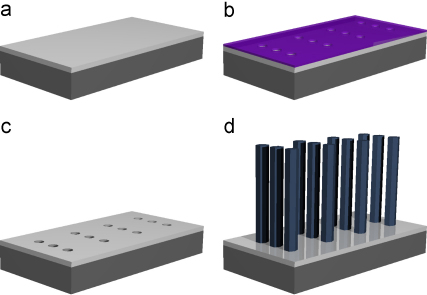

Fig. 1.

Schematics of pattern creation and nanowire growth. (a) Si substrate with the oxide layer. (b) Openings in the PMMA after EBL exposure and development. (c) Substrate with openings in the oxide layer after the PMMA is removed. (d) Position controlled InAs nanowires after growth.

3. Experiments and discussion

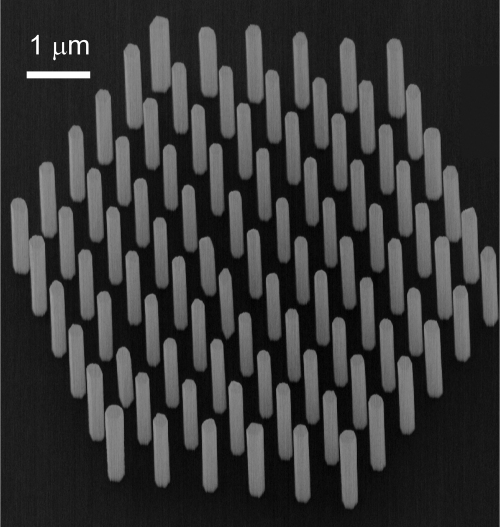

Using the growth method described above, well controlled nanowire growth can be achieved, as is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Demonstration of well controlled nanowire growth with 100% yield. The wires are 3.38 in length and 231±36 nm in diameter. As growth parameters a growth temperature of 550 °C, for TMI and AsH3 molar fractions of 3.9×10−6 and 2.8×10−4, respectively, and a growth time of 4 min has been used. The sample is tilted 20° in the SEM image.

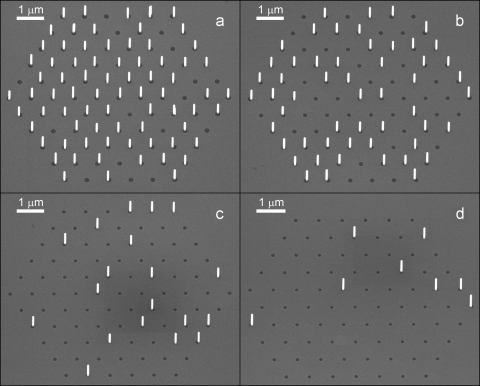

A series of equal patterns with different opening dimensions was created on single samples. The opening sizes varied from 85 nm to 220 nm (in total of 12 different opening sizes in this range), and they were arranged in regular triangles with a 800 nm pitch. Four of these patterns are shown in Fig. 3. For this sample TMI and AsH3 molar fractions of 3.9×10−6 and 2.8×10−4 were used, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Position controlled growth of InAs nanowires on a Si (111) substrate. The opening sizes in these images are (a) 180 nm, (b) 165 nm, (c) 140 nm, (d) 130 nm. The sample is tilted by 30° in the image.

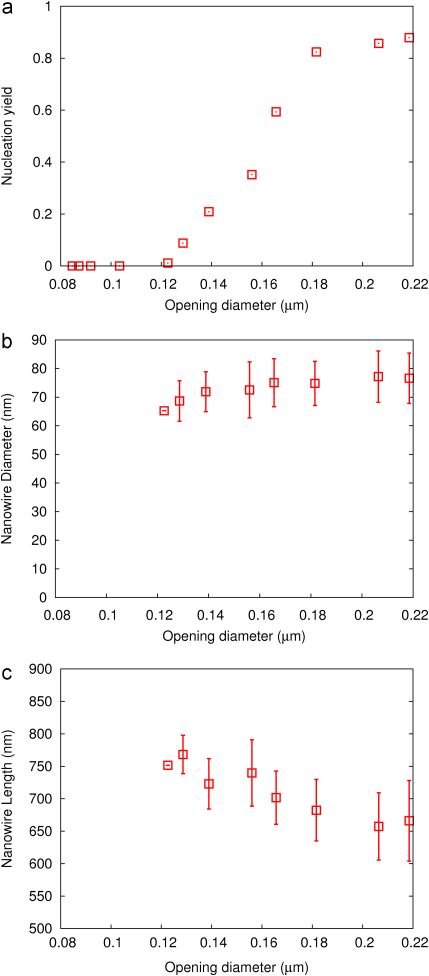

In Fig. 4 the nucleation yield, nanowire diameter and nanowire length are shown as a function of the opening diameter. The opening size has a significant influence on the yield of the nanowire nucleation. The yield is here defined as number of openings nucleating nanowire growth divided by the total number of openings in the pattern. As can be seen in Fig. 4(a), the yield decreases drastically with decreasing opening size.

Fig. 4.

Plot of the (a) nanowire nucleation yield, (b) diameter, and (c) length of the nucleated nanowires over opening diameter. For the yield no error bars are given, as it is determined from a single pattern only. For the nanowire diameter and length the error bars represent the standard deviation of the nanowire diameters and lengths. For the data point without error bar only a single wire was found inside the pattern.

The observed diameter of the nanowires that do form is shown in Fig. 4(b). This diameter is almost independent of the opening size, except for the two left most data points where a slight decrease in the diameter is found, but still within the diameter distribution of the other samples. This shows that the diameter of the wire is not determined by the opening size, but rather by other factors. In previous work, we have reported evidence that the growth is nucleated by a liquid indium particle, the size of which likely determines the initial nanowire diameter [14]. In this process the particle is formed in the initial growth stage without any intentional seeding. Self-seeded growth thus perfectly explains the observed independence of wire diameter from the opening size.

As can be seen in 4(c), we find an indication for an increase in nanowire length with decreasing opening size. As the FWHM of the data is quite large it is hard to clearly interpret this effect. It could be due to the decreasing yield observed with decreasing opening size, which leads to more material available for the nanowires that do grow. As already discussed by various groups [19–21], the nanowire growth rate depends on the surface diffusion of the group III material. Another possibility might be that simply slight variations in nanowire size lead to variations in nanowire length.

The decrease in the yield shown Fig. 4(a) can be caused by two effects: the first effect is that smaller openings lead to smaller collection areas for indium, hence decreasing the probability of an opening to form a seed particle. Since the wire to wire distance most likely is smaller than the indium diffusion length, once a wire starts growing, the indium seed particle will act as a sink and collect a considerable amount of indium from the surrounding surface, as will be discussed in detail below, reducing the probability for formation of additional seed particles nearby.

The second effect is that the openings re-oxidize during the loading of the sample after the final HF dip, and that it takes longer for a larger opening to be covered by an oxide layer than for a smaller one. As we know that on a SiO2 surface nanowire growth is not possible (otherwise we should have nanowire growth on the entire sample surface), there is a critical thickness of the SiO2 layer below which nanowire growth is possible. As the oxidation is independent of position, at each point there is a certain probability for oxidation to take place. As we have not reached the critical oxide thickness (otherwise nanowire growth is not possible) the oxidation process was stopped before. The probability for a full oxide coverage of critical thickness during the loading time is much higher in smaller openings. The critical thickness is harder to reach the larger the opening is. Therefore, even for the case that the oxidation mechanism is vertical, the opening size has an influence.

In both cases, the yield is directly connected to the initial opening size and can in this work not be distinguished.

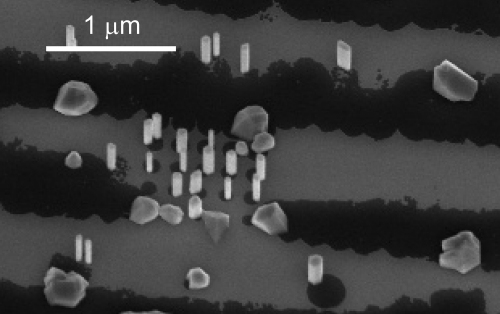

To understand more about the influence of the opening size on nucleation, further samples were investigated, on which large areas of the SiO2 layer have been etched away (500 nm– wide, up to several long), while in between also areas with arrays of smaller openings (up to in diameter) have been fabricated. The growth itself was performed with a molar fraction of 3.1×10−6 and 1.5×10−3 for TMI and AsH3, respectively. On such samples we find that in the small openings a high yield of nanowire nucleation can be achieved, while when large areas of the Si surface are exposed, large crystallites of InAs with no distinct preferential growth direction are found instead of nanowires, as shown in Fig. 5. This clearly demonstrates that the seed particle size is critical for nanowire nucleation, and that seed particles larger than a critical size around do not nucleate wires. Due to the high growth rate and growth conditions used in a MOVPE system it is not possible to probe the time dependence of the nucleation directly.

Fig. 5.

SEM image of a pattern in which large and small areas of the substrate surface are exposed, showing both wire and crystallite growth.

As can be seen in Fig. 5 the number of crystallites is smaller than the number of nanowires. The crystallites seem to be separated by roughly the diffusion length of indium ad-atoms on the Si surface which is in the order of , consistent with the increase in axial growth rate with decreasing nanowire yield, as discussed above. Indium droplets closer together will most likely merge by atom migration, leading to a ripening effect and merging of indium particles due to their movement [22,23] collecting all the material in larger particles. This mobility of indium particles is suppressed by an immobilization effect of the SiO2 layer leading to smaller indium particles in the small openings which nucleate nanowire growth and to the position controlled nanowire growth observed here.

In previous work we studied the mobility of indium droplets on a clean InAs substrate and a substrate covered with a thin SiOx mask layer. Indium particles on a clean InAs surface are very mobile and form large droplets [14]. The indium droplets on the oxide covered surface are immobilized and typically a high density of small droplets is found. In case of the samples with a clean substrate surface such a suppression of indium particle movement does not exist and in a quite short time indium particles of size can form. The SiO2 mask used in this work is expected to have the same influence on indium particle movement, leading to small indium particles and nanowire growth in small openings () and large indium particles and crystallite formation in large openings ().

The findings from Fig. 5 clearly contradict the case of selective area growth (SAG), as proposed in [5]. For SAG the entire clean Si surface seen in Fig. 5 should lead to InAs growth. Furthermore, nanowires grown according to the SAG mechanism should cover the entire size of the opening, assuming that no oxidation has occurred. In case the openings do oxidize, the nanowires diameter should correspond to that of the remaining clean Si surface. In both cases this should result in a clear correlation between opening size and nanowire diameter, in contradiction to our findings.

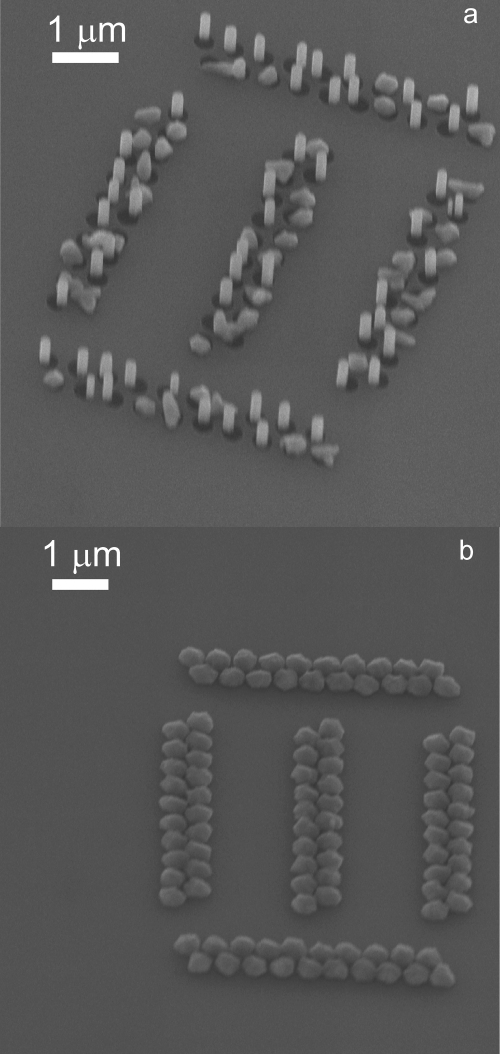

To verify the finding that indium droplets above a critical size do not nucleate InAs nanowire growth we compared the results of several growth runs with and without intentional indium pre-deposition. In the following we discuss the indium pre-deposition for 0 s, 1 s, and 16 s, after which the AsH3 was activated to initiate nanowire growth. For the samples with a pre-deposition of 1 s and 16 s a molar fraction of 4.0×10−6 a molar fraction of 7.4×10−4 for TMI and AsH3 is used, respectively. For the sample without pre-deposition the TMI and AsH3 molar fractions were 3.9×10−6 and 2.8×10−4, respectively. As can be seen in Fig. 3, a high yield of nanowire growth can be achieved without indium pre-deposition. If a small amount of indium is pre-deposited, more than half of the nucleated structures are nanowires, but several larger structures form in the openings, as shown in Fig. 6(a). If the indium pre-deposition is further increased, only large crystallites are found, as can be seen in Fig. 6(b). It is interesting to mention that the crystallites cover all the space between two openings, suggesting that the indium particles that formed during indium deposition might have even been larger than the openings.

Fig. 6.

SEM image of InAs growth following a 1 s (a), and a 16 s (b) indium deposition prior to growth, leading to large crystallites for 16 s indium pre deposition. The samples are seen under 45° tilt.

With these experiments, we demonstrated that the role of the oxide mask layer is to limit the mobility of the indium particles to the oxide openings, where nanowire nucleation occurs, and by that position control is achieved. We clearly show that nanowires only nucleate if indium droplets smaller than are provided, which is the case inside openings within a certain diameter range. The yield of nanowires can be increased using openings small enough to prohibit the formation of “large” indium droplets, indicating that the oxide layer reduces the surface mobility of indium droplets. Too small openings, however, lead to a reduction in nucleation, as discussed above.

As mentioned already in previous work [14], we found that the nanowire length as well as the diameter is influenced by the growth time. A sample series was grown in which only the growth time was changed. For this growth molar fractions for TMI and AsH3 of 3.1×10−6 and 1.5×10−3 were used, respectively. The nanowire diameter changes from 47±5 nm to 1300±190 nm and the length from to when increasing the growth time from 30 s to 16 min. As the indium particle on the wire top is not fixed in size but consists of material provided during the entire growth process this particle continuously grows, and consequently also the wire diameter. Interestingly, once the nanowire growth is nucleated, wires with quite large diameter can still maintain the axial growth as was the case for the wires grown for the longest time. It should be noted that once axial growth is initiated, the diameter of the wire and by that of the particle as well can become larger than the proposed maximum particle size for the initial nucleation of nanowire growth.

Even for the deposition of a large amount of indium and InAs on the samples, no substantial growth on the SiO2 mask layer was found. This could be connected to a very short time which the indium ad-atoms remain on the layer before they desorb again, or it could also be connected to a certain “transparency” of the mask layer for indium (such an effect was found in Ref. [14]) leading to a transport of indium inside this layer, separating it from the AsH3 and by that preventing any growth on the layer. Unfortunately our experiments do not allow to clearly identify why no indium droplets on the SiO2 mask form and nucleate nanowire growth and why no InAs layer growth can be observed on the SiO2 surface.

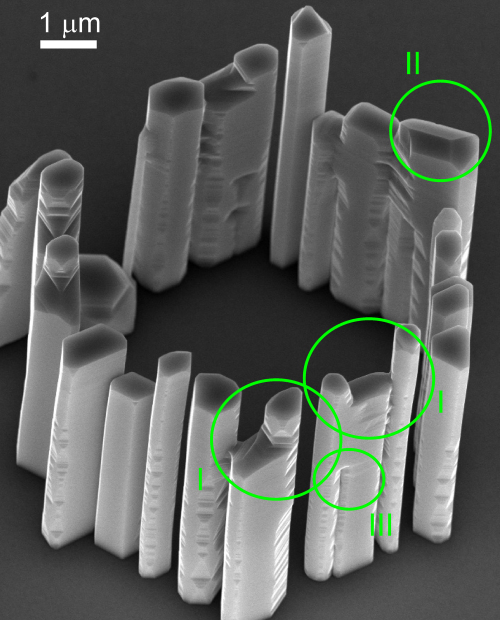

As described for extended growth times, the diameter of the wires continuously increases. The use of position controlled growth in such a case can lead to a merging of wires. If this is to be prevented, the growth time has to be decreased, or the distance between the openings increased. This puts some restrictions to self-seeded position controlled wire growth. Fig. 7 shows an example, for an extended growth time which led to nanowire coalescence.

Fig. 7.

SEM image of a pattern with merged wires. In circles I the merging of two wires with different lengths can be seen. The longer wire continues with a hexagonal cross section, while the cross-section of the shorter wire becomes deformed, most probably by the indium particle of the shorter wire wetting of the longer wires side facets. Circle II highlights two wires of the same length that have merged, both Indium particles merge into one elliptic particle and the wire continues growth as one structure. In circle III the filling of the groove created by the side facet orientation of the original wires can be seen, the circle is placed at the position where the transition between the filled groove to the empty groove is found. The position indicates the earliest possible point where the merging first occurred. The sample is tilted by 30°.

Several features of such merged structures are quite striking. In most cases two wires that meet are of different length. As the particle on top of the longer wire is not affected, this wire continues growth without any change in its cross section. For the shorter wire, however, the indium particle will wet the side facets of the longer wire. This deforms the In seed particle on top of the shorter wire, which leads to a deformed cross section of the following axial growth of the shorter nanowire. The results of such a merging can be seen in circle I in Fig. 7.

A different situation can be seen in Fig. 7 marked by the circle II, where two nanowires of similar lengths have merged. Our interpretation is that at some stage during growth the indium seed particles have merged, leading to growth of one nanowire with an elongated hexagon as cross-section under a single particle.

Next we consider the grooves created by the merging of the wires due to their cross section. At the point where two nanowires merge, it is reasonable to assume, that due to the deformation of one or both indium particles, from that point on the groove is directly filled by the axial wire growth. The high curvature of the surface just below the point when two wires have merged promotes nucleation. This leads to an increased growth speed for the downward filling of the grooves between merged nanowires, whereby a sharp step in the groove is formed, as shown in circle III of Fig. 7.

We expect these two effects, particle deformation and preferential filling of the grooves, to lead to the observed shape of the nanowire side facets for merged nanowires.

4. Conclusion

The set of experiments performed in this work clearly demonstrates three properties of self-seeded nanowire growth on pre-patterned substrates:

-

(i)

InAs nanowire growth under the used parameters is due to self-seeded particle assisted growth based on indium particles [14].

-

(ii)

There is an optimum indium particle size range for nanowire nucleation; indium particles outside of this range do not lead to nanowire growth under the growth conditions studied here.

-

(iii)

The SiO2 mask used in this work restricts indium particle movement, leading to small indium droplets and nanowire growth in small openings () and large indium droplets and crystallite formation in large openings (). The observations strongly indicate that the nanowires are nucleated by a liquid indium particle and contradict the case of selective area growth.

In summary we have shown that holes in a SiO2 mask act not only as the position control for InAs nanowire growth, but also as a control for the nucleating seed particle size. In too large openings, where ripening effects and merging of indium particles can occur, nanowire growth is not observed and crystallites are grown. Moreover, characterization of the nanowire dimensions shows that these are not determined by the opening size but mainly by the growth time. Furthermore, changes in the wire morphology for merging of pairs of nanowires was demonstrated. The present work shows that for self-seeded nanowire growth a certain range of optimal particle dimension exists which makes nanowire growth possible.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out within the Nanometer Structure Consortium at Lund University (nmC@LU) and was supported by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SSF), the Swedish Research Council (VR), and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the EU Projects NODE (cont. no. 015783), SANDiE (cont. no. NMP4-CT-2004-500101), AMON-RA (cont. no. 214814) and by the FWF Vienna by the SFB project IRON (F2507-N08).

Communicated by J.M. Redwing

References

- 1.Thelander C., Agarwal P., Brongersma S., Eymery J., Feiner L.F., Forchel A., Scheffler M., Riess W., Ohlsson B.J., Gösele U., Samuelson L. Nanowire-based one-dimensional electronics. Materials Today. 2006;9:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu X., Lin Y., Zhou S., Sheehan S., Wang D. Complex nanostructures: synthesis and energetic applications. Energies. 2010;3:285–300. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan Z., Ruebusch D.J., Rathore A.A., Kapadia R., Ergen O., Leu P.W., Javey A. Challenges and prospects of nanopillar-based solar cells. Nano Research. 2009;2:829–843. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y., Qian F., Xiang J., Lieber C.M. Nanowire electronic and optoelectronic devices. Materials Today. 2006;9:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomioka K., Motohisa J., Hara S., Fukui T. Control of InAs nanowire growth directions on Si. Nano Letters. 2008;8:3475–3480. doi: 10.1021/nl802398j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokkapati S., Jagadish C. III–V compound SC for optoelectronic devices. Materials Today. 2009;12:22–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cantoro M., Wang G., Lin H.C., Klekachev A.V., Richard O., Bender H., Kim T.G., Clemente F., Adelmann C., van der Veen M.H., Brammertz G., Degroote S., Leys M., Caymax M., Heyns M.M., De Gendt S. Large-area, catalyst-free heteroepitaxy of InAs nanowires on Si by MOVPE. Physica Status Solidi (a) 2010;208:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roest A.L., Verheijen M.A., Wunnicke O., Serafin S., Wondergem H., Bakkers E.P.A.M. Position-controlled epitaxial III/V nanowires on silicon. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:S271–S275. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björk M.T., Schmid H., Bessire C.D., Moselund K.E., Ghoneim H., Karg S., Lörtscher E., Riel H. Si-InAs heterojunction esaki tunnel diodes with high current densities. Applied Physics Letters. 2010;97:163501. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plissard S., Dick K.A., Larrieu G., Godey S., Addad A., Wallart X., Caroff P. Gold-free growth of GaAs nanowires on silicon: arrays and polytypism. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:385602. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/38/385602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koblmüller G., Hertenberger S., Vizbaras K., Bichler M., Bao F., Zhang J.P., Abstreiter G. Self-induced growth of vertical free-standing InAs nanowires on Si(111) by molecular beam epitaxy. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:365602. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/36/365602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandl B., Stangl J., Mårtensson T., Mikkelsen A., Eriksson J., Karlsson L.S., Bauer G., Samuelson L., Seifert W. Au-free epitaxial growth of InAs nanowires. Nano Letters. 2006;6:1817–1821. doi: 10.1021/nl060452v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mårtensson T., Wagner J.B., Hilner E., Mikkelsen A., Thelander C., Stangl J., Ohlsson B.J., Gustafsson A., Lundgren E., Samuelson L., Seifert W. Epitaxial growth of indium arsenide nanowires on silicon using nucleation templates formed by self-assembled organic coatings. Advanced Materials. 2007;19:1801–1806. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandl B., Stangl J., Hilner E., Zakharov A.A., Hillerich K., Dey A.W., Samuelson L., Bauer G., Deppert K., Mikkelsen A. Growth mechanism of Self-Catalyzed group III–V nanowires. Nano Letters. 2010;10:4443–4449. doi: 10.1021/nl1022699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khayer M.A., Lake R.K. Diameter dependent performance of high-speed, low-power InAs nanowire field-effect transistors. Journal of Applied Physics. 2010;107:014502. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gudiksen M.S., Lauhon L.J., Wang J., Smith D.C., Lieber C.M. Growth of nanowire superlattice structures for nanoscale photonics and electronics. Nature. 2002;415:617–620. doi: 10.1038/415617a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samuelson L. Self-forming nanoscale devices. Materials Today. 2003;6:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka T., Tomioka K., Hara S., Motohisa J., Sano E., Fukui T. Vertical surrounding gate transistors using single InAs nanowires grown on Si substrates. Applied Physics Express. 2010;3:025003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansson J., Svensson C.P.T., Mårtensson T., Samuelson L., Seifert W. Mass transport model for semiconductor nanowire growth. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2005;109:13567–13571. doi: 10.1021/jp051702j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tchernycheva M., Travers L., Patriarche G., Glas F., Harmand J.C., Cirlin G.E., Dubrovskii V.G. Au-assisted molecular beam epitaxy of InAs nanowires: growth and theoretical analysis. Journal of Applied Physics. 2007;102:094313. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubrovskii V.G., Sibirev N.V., Cirlin G.E., Harmand J.C., Ustinov V.M. Theoretical analysis of the vapor–liquid–solid mechanism of nanowire growth during molecular beam epitaxy. Physical Review E. 2006;73:021603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.021603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilner E., Zakharov A.A., Schulte K., Kratzer P., Andersen J.N., Lundgren E., Mikkelsen A. Ordering of the nanoscale step morphology as a mechanism for droplet Self-Propulsion. Nano Letters. 2009;9:2710–2714. doi: 10.1021/nl9011886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tersoff J., Jesson D.E., Tang W.X. Running droplets of gallium from evaporation of gallium arsenide. Science. 2009;324:236–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1169546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]