Abstract

Background and objective

The birth of a preterm infant can be an overwhelming experience of guilt, fear and helplessness for parents. Provision of interventions to support and engage parents in the care of their infant may improve outcomes for both the parents and the infant. The objective of this systematic review is to identify and map out effective interventions for communication with, supporting and providing information for parents of preterm infants.

Design

Systematic searches were conducted in the electronic databases Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, the Cochrane library, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Midwives Information and Resource Service, Health Management Information Consortium, and Health Management and Information Service. Hand-searching of reference lists and journals was conducted. Studies were included if they provided parent-reported outcomes of interventions relating to information, communication and/or support for parents of preterm infants prior to the birth, during care at the neonatal intensive care unit and after going home with their preterm infant. Titles and abstracts were read for relevance, and papers judged to meet inclusion criteria were included. Papers were data-extracted, their quality was assessed, and a narrative summary was conducted in line with the York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines.

Studies reviewed

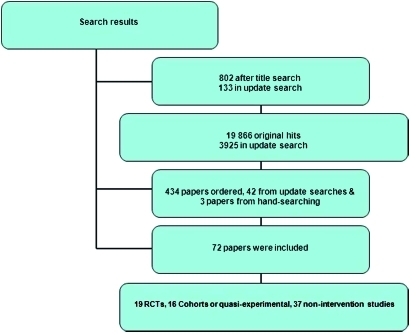

Of the 72 papers identified, 19 papers were randomised controlled trials, 16 were cohort or quasi-experimental studies, and 37 were non-intervention studies.

Results

Interventions for supporting, communicating with, and providing information to parents that have had a premature infant are reported. Parents report feeling supported through individualised developmental and behavioural care programmes, through being taught behavioural assessment scales, and through breastfeeding, kangaroo-care and baby-massage programmes. Parents also felt supported through organised support groups and through provision of an environment where parents can meet and support each other. Parental stress may be reduced through individual developmental care programmes, psychotherapy, interventions that teach emotional coping skills and active problem-solving, and journal writing. Evidence reports the importance of preparing parents for the neonatal unit through the neonatal tour, and the importance of good communication throughout the infant admission phase and after discharge home. Providing individual web-based information about the infant, recording doctor–patient consultations and provision of an information binder may also improve communication with parents. The importance of thorough discharge planning throughout the infant's admission phase and the importance of home-support programmes are also reported.

Conclusion

The paper reports evidence of interventions that help support, communicate with and inform parents who have had a premature infant throughout the admission phase of the infant, discharge and return home. The level of evidence reported is mixed, and this should be taken into account when developing policy. A summary of interventions from the available evidence is reported.

Keywords: Social Health, community child health, paediatric intensive and critical care, education and training, quality in healthcare

Article summary

Article focus

A systematic mapping review to identify and synthesise evidence of effective interventions for communicating with, supporting and providing information for parents of preterm infants.

Key messages

The review highlights the importance of encouraging and involving parents in the care of their preterm infant at the neonatal unit to enhance their ability to cope with and improve their confidence in caring for the infant, which may also lead to improved infant outcomes and reduced length of stay at the neonatal unit.

Interventions for supporting parents included: (1) involving parents in individualised developmental and behavioural care programmes (eg, Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE), Neonatal Individualised Developmental Care and Assessment Programme, Mother–Infant Transaction Programme (MITP)) and behavioural assessment programmes; (2) breastfeeding, kangaroo-care and infant-massage programmes; (3) support forums for parents; (4) interventions to alleviate parental stress; (5) preparation of parents for various stages—for example, seeing their infant for the first time, preparing to go home; (6) home-support programmes.

Involving parents in the exchange of information with and between health professionals is important, with various modes of providing this information reported—for example, ward rounds with doctors, discussion around infant notes, websites and hard-copy information.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths

This is the first review to synthesise the evidence of interventions to support parents of preterm infants through improved provision of information, improved communications between parents and health professionals, and alleviation of stress at all stages of a parent's journey through the neonatal unit. It highlights relatively inexpensive interventions that can be integrated into their pathway through the neonatal unit and return home, enhancing parental coping and potentially improving infant outcomes and reducing the infants length of stay at the neonatal unit.

Limitations

The quality of the evidence that this review reports is variable, and includes all types of study designs. It has been difficult to evaluate one piece of evidence over another because of the nature of the evidence. For example, whether randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are an appropriate method of evaluating the parents' experiences of interventions over and above, say, a qualitative study is debatable. While the RCT studies are more objective, they often fail to provide a more in-depth empirical reality of parents' experiences of having a premature infant. A well-conducted RCT may not provide a true reflection of improved self-esteem or empowerment, for example, whereas a qualitative study provides an understanding of the experiences. Furthermore, evaluation of such complex interventions is challenging because of the various interconnecting parts of the pathway reported in figure 2.

It is therefore very difficult to evaluate the results to say that one study method is better than another. For this reason, we have been inclusive in our selection of studies, resulting in a large number of studies selected for the review. Being inclusive of studies benefits the evidence base by bringing together ‘experience’ studies in a systematic way gaining a greater breadth of perspectives and a deeper understanding of issues from the point of view of those targeted by the interventions. However, if studies were fatally flawed, they were excluded from the review.

Introduction

While medical advances mean that very premature neonates have an increasingly better chance of survival, the impact of this experience on the child and their parents cannot be underestimated. The birth of a preterm infant can be an intensely stressful, confusing and difficult time for parents and families.1 Parents can have feelings of fear about their infant's condition or doubt in their ability to care for the child. Parents may also experience anger or grief, or they may blame themselves and experience intense guilt. Once mothers have returned home, hospital visits to see their baby can be difficult if coping with other siblings and travelling long distances to the neonatal unit.2 It is therefore not surprising that mothers of preterm babies experience significantly higher levels of postnatal depression than mothers of healthy full-term infants.3 Fathers, who are often the main source of comfort and support for their wives, report feeling powerless to help, and often feel isolated from their infant as the health professionals focus on the infant and mother.4

Furthermore, while going home with their infant can be a time of joy and relief for these parents, bringing home a fragile infant and caring for them for the first time can be a worrying time, causing additional stress for the parents.

Reducing parent stress and introducing interventions to improve parents' confidence and ability to care for their premature infant at the neonatal unit and after returning home can improve outcomes for parents and their child, reduce the length of stay at the neonatal unit5 6 and reduce the readmittance to hospital.7

The Parents of Premature Babies (POPPY) study aims to develop a better understanding of the experiences of a range of parents with preterm infants, particularly with regards to the communication, information and support they received on the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), ensuring that the perspectives of parents are at the heart of the study.8 This paper reports the results of the first phase of the POPPY study, which takes the form of a systematic mapping review to identify effective interventions for communicating with, supporting and providing information for parents of preterm infants.

Methods

Systematic searches were undertaken for the period of January 1980 to October 2006 in the following databases: Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, the Cochrane library, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Midwives Information and Resource Service, Health Management Information Consortium, and Health Management and Information Service (see online table 1 for search strategy). A combination of text terms and MeSH terms were used to maximise the volume of literature retrieved. Grey literature was sought from specialists in the field, and the following journals were hand-searched from 1990 onwards for all relevant English-language articles: Neonatal Network Journal, Journal of Neonatal Nursing and Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. Update searches were undertaken in October 2009.

Studies were included if they met the inclusion criteria:

outcomes reported by parents who have had a preterm infant (ie, ≤36 weeks' gestation);

provided parent-reported outcomes (ie, outcomes were reported by the parent themselves, not reported by health professionals or others) of interventions relating to information provision at the neonatal unit and after discharge;

provided parent-reported outcomes of interventions relating to communication with health professionals at the neonatal unit and after discharge;

provided parent-reported outcomes of interventions relating to provision of support at the neonatal unit and after discharge;

design of study was: RCTs, quasi-experimental, cohort, case–control, cross-sectional, case series, case reports or qualitative;

studies were relevant to that of developed countries;

passed quality assessment;

published between January 1980 and October 2009;

English language.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following exclusion criteria:

reported parent-reported outcomes of parents who had a sick full-term infant at the neonatal unit;

outcomes were not reported by parents (eg, evaluation of parent intervention by health professionals);

editorials or opinions;

study was fatally flawed;

not English Language;

published before January 1980.

It was felt that the systematic review should be inclusive of all study designs, as it is often not feasible or appropriate to conduct randomised control trials (RCTs) or other intervention studies on the outcomes for parents that were measured. Therefore, despite the potential bias inherent in descriptive studies, it was deemed that the results of these studies nonetheless gave an important insight into parent-related interventions and should be included in this review.

The data-extraction form and quality assessment for inclusion criteria were based on the guidelines from the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (NHS CRD).9 Initially, two reviewers extracted data (JB, SS) independently for 20% of papers, and disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. There was a high level of agreement between reviewers, so the remaining data were extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. The quantitative studies covered a wide range of interventions and different methods of assessment, so it was not possible to carry out a meta-analysis. A non-quantitative synthesis was conducted based on the extracted data. In the summary figure (figure 2), the included evidence was assessed using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Assessment.10

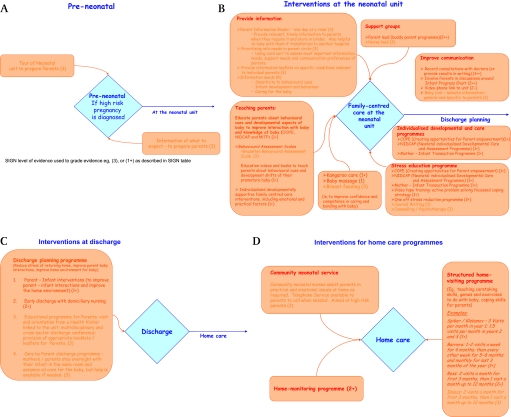

Figure 2.

Summary of evidence for interventions at the neonatal unit and after discharge.

Search results

Figure 1 indicates the search results for the review. Seventy-two papers were included (four were deemed relevant in two of the sections). Papers were excluded for a number of reasons including the fact that no parent outcome was identified, the study was irrelevant to neonatal services offered in developed countries such as the UK,3 or the study was deemed to be fatally flawed.11

Figure 1.

Results from the literature search.

Online tables 2a to 2j report the data extraction by sections described in the Results section. Figure 2 provides a summary of evidence for interventions at the neonatal unit and after discharge.

Results

Interventions for supporting parents included: (1) individualised developmental and behavioural care programmes4 11–17 (eg, Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE), Neonatal Individualised Developmental Care and Assessment Programme (NIDCAP), Mother–Infant Transaction Programme (MITP)—see below); (2) behavioural assessment scales; (3) breastfeeding, kangaroo-care and infant-massage programmes; (4) support forums for parents; (5) the alleviation of parental stress; (6) preparing parents for seeing their infant for the first time; (7) communication and information sharing; (8) discharge planning; and (9) home-support programmes.

Supporting parents through individualised developmental and behavioural care programmes

Fourteen studies reported individualised developmental and behavioural care programmes, of which nine were RCTs. The RCT evidence (1++ and 1+) suggested that the involvement of parents in an individualised developmental and behavioural care programme significantly reduced the maternal stress created by the NICU environment and the demands of their infant.4 11 14 16 18 19 This intervention also significantly improved the parental understanding of their infant and their interactions with their infant4 (box 1).

Box 1. Individualised developmental and behavioural care programmes.

COPE4 (Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment) provides an educational programme for parents at the neonatal unit on the appearance and behavioural characteristics of preterm infants, how parents can participate in their infant's care and how parents can make more positive interactions with their infant

NIDCAP11–13 (Neonatal Individualised Developmental Care and Assessment Programme) is an intervention that stimulates preterm infants and improves the interaction between mothers and infants

MITP (Mother–Infant Transaction Programme)14–16 helps to enable the parents to appreciate their infant's unique characteristics, temperament and developmental potential, sensitising parents to their infant's cues so that can respond appropriately

NCATS (Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale)17 examines the mother–child relationship in conjunction with teaching mothers how to interact with the baby, teaching behavioural cues, how to play, etc

NB: While the developmental care programmes are designed to improve the development of the baby, these interventions give parents psychological support and practical guidance on how to care for their infants.

Recent RCT evidence suggested that the introduction of the NIDCAP intervention had not significantly changed levels of parental stress, confidence or nursing support. However, the outcomes were measured only 1–2 weeks after the baby was born (1+).12 The introduction of the Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale programme in the NICU made no significant difference to parental stress levels and maternal–infant interactions when assessed at discharge and at 3 months after discharge (1+).20 One RCT found that coaching parents on how to interact with their preterm infant made no difference to knowledge of care, sensitivity to the infant or satisfaction in parenting compared with the control group (1–).21 However, this may have been confounded by the amount of contact that the control mothers had with the researchers, as these mothers reported that they enjoyed having someone show an interest in them.

Evidence from a cohort reported that the Vermont Mother–Infant Transaction Programme (MITP) significantly improved maternal satisfaction, maternal self-confidence and mothers' perception of their infant's temperament at 6 months.15 One cohort study reported that individualised developmental care programmes appeared to make no difference to parents' perceptions of the neonatal unit or satisfaction with care, despite significantly lowering stress cues in the preterm infants.22

Evidence from qualitative studies provides an insight into the benefits of individualised developmental and behavioural care programmes at the neonatal unit, such as empowering parents to take care of their infants, teaching parents behavioural cues of their infants, problem-solving and learning how to interact with their infants, resulting in a greater satisfaction with the care provided.13 23 24 Furthermore, parents reported a reduction in stress after such programmes and said that they felt more confident in caring for their infants, which promoted parental self-reliance when returning home.24

Supporting parents through the use of Behavioural Assessment Scales

No RCT evidence was reported on this intervention. Three cross-sectional studies provided insights into how to teach parents to assess and interpret the behaviour of their preterm by using the Brazelton Behavioual Assessment Scales. The studies reported this intervention may improve mother–infant bonding, reduce maternal anxiety and help mothers foster a more realistic perception of their preterm infants.25–27

Supporting parents through breastfeeding, kangaroo care and infant massage

Four studies reported on parent outcomes of interventions around breastfeeding, of which one was an RCT; six studies reported on parent outcomes of interventions around kangaroo care (skin-to-skin contact with baby out of the incubator), of which two were RCTs; and two studies reported parent outcomes around baby massage. An RCT (1−) reported no significant difference in the mother's confidence and competence in carrying out breastfeeding by weighing the infant before and after feeds.28

Three cross-sectional studies and one case series study reported on breastfeeding interventions. The studies reported that parents receiving breastfeeding support at the neonatal unit were more likely to continue breastfeeding up to a month after discharge than comparable groups. Breastfeeding education and support at the neonatal unit in the form of counselling, information (handouts and videos), practical help and group breastfeeding clinics improved the confidence of mothers in breastfeeding. An individualised discharge plan for breastfeeding mothers with follow-up telephone calls or home visits appeared to maintain mothers' confidence in breastfeeding and provide reassurance.29–31

Six studies reported parent outcomes of using kangaroo care with their preterm infants, of which two were RCTs. The RCT evidence (1+) suggests that the use of kangaroo care significantly reduces maternal anxiety around her infant and gives the mother a significantly greater sense of competence with their infant and a significantly greater sensitivity towards her infant.32 Furthermore, RCT evidence (1+) suggests that music during kangaroo care resulted in significantly lower maternal anxiety.33

One cohort study, which assessed outcomes of mothers using kangaroo care at 37 weeks, 3 months and 6 months reported significantly better levels of mother–infant interaction, more touch, better adaptation to infant cues and better perception of their infant at all time periods. Mothers also reported significantly less postnatal depression compared with the controls at 37 weeks.34

One cross-sectional study reported that the majority of mothers preferred the kangaroo method, mainly because their baby was closer to them. Touch was important to mothers, as it induced feelings of well-being and fulfilment in parents.35

In the qualitative studies, parents described how kangaroo care helped them to get to know their infant, increased their confidence and made them feel that their infant needed them36; parents reported that their mood was improved and that they perceived their infant differently and felt a stronger sense of identifying with their infant.37

Two studies reported on parent outcomes of baby massage on preterm infants, of which one was an RCT. RCT evidence (1+) reported that at 3 months, mothers of massaged infants felt significantly less intrusive towards caring for their baby, interactions were more reciprocal, and treated infants were more socially involved than controls.38 One cross-sectional study also reported improved maternal–infant interactions.39

Support forums for parents

No RCT evidence was reported for these interventions. Nine studies reported the benefits of participating in support groups set up within the NICU, either run by staff at the neonatal unit or run by parents who have experienced having a preterm infant themselves. Evidence from cohort studies reported that parent-led peer support groups at the NICU led to mothers in the intervention group having significantly less stress at 4 weeks and 16 weeks after support was initiated at the neonatal unit.40 41 Mothers of critically ill preterm infants had significantly better maternal mood states, maternal–infant relationships and home environments in the intervention group than the control group.42

Evidence from a qualitative study gave insights into how a health Professional-led support group assisted parents to gain perspective, feel supported and learn practical information about how to interact with their baby.43 Qualitative evidence also reports that parent-to-parent support groups provided parents with information, emotional support and strength.44 Cross-sectional studies and case-series studies reported on how health Professional-led support groups also helped to relieve anxiety, gave parents an opportunity to communicate with staff and helped parents gain confidence in their parenting skills.45–47 Another case-series study reported how a support programme run by parents gave parents space to express their worries and concerns, and provided comfort in talking to ‘experienced’ parents.48

Alleviating parent stress

Seven studies report interventions that attempt to alleviate the adverse psycho-social consequences of having a preterm infant, of which four were RCTs. RCT evidence (1+ to 1++) is reported in the individualised developmental behavioural programme section for the stress-reduction benefits of COPE, NIDCAP and MITP.4 11 14 16 Other RCT evidence (1−) reports that the use of videotape in strategies that focus on coping with emotions and active problem-solving significantly reduced maternal stress.49

Evidence from a cohort study reported that the use of one-off psychological interventions to teach relaxation and coping mechanisms to normalise their experience, as well as emotional and practical support, significantly reduced the traumatic impact for parents compared with controls.50 Two case-series studies gave insights into the use of journal writing for documenting feelings, thoughts, milestones and involvement in care; the use of psychotherapy to offer support and insight at a time of crisis was also found to reduce stress.51 52

Preparing parents for seeing their infant at the neonatal unit for the first time

Two studies reported evidence for different ways of preparing parents for seeing their preterm infant for the first time, one of which was an RCT.53 54 The RCT evidence (1+) reported that giving parents a photograph of their preterm infant provides a positive effect by improving bonding with their infant.53

The qualitative study gave an insight into how a tour of the neonatal unit prior to having a preterm infant (when a pregnancy at high risk of premature labour was diagnosed) may decrease parent's fears, inspire hope in their infant's prognosis and give parents reassurance about the care offered at the NICU.54 However, some parents found the appearance of the babies and the technology overwhelming, and some expressed concerns that the tour was not supported by staff on the neonatal unit.

Interventions for communication and information sharing

Eight studies assessed interventions to improve the issues of communication at the neonatal unit, one of which was an RCT.55 The RCT evidence (1+) reported that taping parent–doctor consultations improved the recall of parents of the consultation.55 The trial found that mothers who received audiotapes of their consultation recalled significantly more information about the diagnosis, treatment and outcome of their infants than women in the control group at 10 days and at 4 months.

Evidence from a cohort study reported that discussions between health professionals and parents around their infant's progress chart resulted in the intervention group having significantly fewer unrealistic concerns, less uncertainty about the medical condition of the infant, less conflict and a greater satisfaction with regards to shared decision-making.56 Another cohort study reported that parents had significantly greater contact with the NICU during the infant's admission and reported a sense of relief at seeing their infant when they had access to the neonatal unit via a videophone.57

Qualitative evidence investigated the perception of parents regarding the methods of effective and ineffective communication at the NICU. Parents perceived the most effective communication with nurses to be through discourse management (nurses asking questions and encouraging parents to ask questions), caring and reassuring communication, and communication as equal partners in the care of the infant. Ineffective communication was perceived as when the information given was inconsistent, when staff did not check if parents understood the information and when questions were not allowed.58 Furthermore, qualitative evidence reported that ‘chat’ or ‘social talk’ between nurses and parents had a positive influence on mothers' confidence, their sense of control and their feeling of connection with their baby.59

Cross-sectional studies provided an insight into the methods of improving communication between parents of preterm infants and health professionals. The use of a web-based programme (BabyLink) to provide individualised information to parents helped communicate complex issues, and parents reported that it helped to humanise the experience of the neonatal unit.60 Furthermore, a study reported that the use of BabyLink improved the overall satisfaction of the family with care at the neonatal unit and actually reduced the length of stay at the neonatal unit.6 Parents reported that they found the tape-recorded consultations with doctors helpful to process the information, as well as being comforting and supportive.61

Five studies reported evidence on the information needs of parents, none of which provided RCT level evidence. One pretest/post-test study concluded that information and training for specific practical care of their infant on oxygen therapy could significantly improve the relevant knowledge of parents and reduced their distress when entering the transition period of returning home.62

Three qualitative studies described an information binder that provided relevant information about medical and practical issues relating to the NICU. Parents could add information to the folder. The information binder empowered parents to take an active interest in acquiring relevant information about their infant and improved parents' understanding and ability to participate in decision-making. Furthermore, the information binder increased parents' confidence in caring for their infant, and gave them hope of progress for their infant.63 64 Prioritising information through a ‘card sort’ (cards that state information topics for parents who have had a preterm infant) was reported by a qualitative study as being a less intimidating way for parents to access important and timely information.65 This study reported that parents' highest priorities were infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation, infant illness and development; information with a moderate priority included feeding, giving medication and hygiene; and information topics that were given the lowest priority included getting help at home and the use of car seats. One cross-sectional study reported that the neonatal nurses were the best source of information at the NICU.66

Discharge planning

Six studies reported on discharge programmes, of which one reported RCT level evidence.67 RCT evidence (1−) suggests that a parent–infant discharge programme within a therapeutic problem-solving model significantly improved parents' interactions with their infants, and parents were significantly more engaged with their infants after returning home than parents who did not go through a discharge programme.67

One cohort study assessed an early discharge programme with an individualised care and discharge plan, followed by domiciliary nursing care, and reported significantly less anxiety in mothers in the intervention group at discharge.68 No significant differences in the experiences of parents with regards to their infant's emotional well-being and breastfeeding issues were reported. The levels of anxiety did not appear to be different between groups of parents who did not receive a formal discharge programme at 1 year after discharge from the neonatal unit.68

The qualitative studies gave insights into how discharge planning provided support for parents. One study conducted a discharge programme that comprised an educational programme during the period of hospitalisation for parents with preterm infants, a visit and orientation about the neonatal unit by the family's health visitor, a multidisciplinary and cross-sector discharge conference, and the publication of relevant booklets for parents and healthcare providers.69 The parents found that most of the intervention initiatives contributed to a feeling of overall increased support and met their needs, including improving their confidence in caring for their preterm infant and ensuring the well-being of their child following discharge. Families valued the support and guidance they received from the co-ordinating health visitor and valued having a named contact nurse throughout their stay at the neonatal unit and at home, which demonstrated the importance of continuity of care. All participants in this study felt secure when they returned home.

One qualitative study assessed the perceptions of parents of preterm infants regarding an early discharge and home-care programme.70 The study concluded that parents of children who were discharged early may feel more positive about coming home as early as possible from the hospital, as this may help parents to feel like a ‘normal’ family and not to have to share their infant with the nurses and other health professionals on the neonatal unit. However, parents in this study appreciated the 24 h accessibility of the staff on the neonatal unit for support and knowledge.

Two further qualitative studies report a Care by Parent discharge programme and describe how the mother can stay in the same room or in a room close to her preterm infant, assuming all of the aspects of care but with help at hand if needed.71 72 Mothers reported that it gave them the opportunity to test reality and bridge the gap between hospital and home, thereby gaining confidence in taking their infant home, and it helped mothers to feel they were part of a proper family and to promote their ‘ownership’ of the infant.

Home-support programmes

Ten studies reported the outcomes of parents who participated in home-intervention programmes, of which two were RCTs. RCT evidence (1−) reported that home-support programmes, where parents are visited and given emotional and practical support regularly for the first year and for up to 3 years afterwards, lead to significantly reduced parental stress levels, a greater positive effect on maternal behaviour and greater interactions with their preterm infant. However, the intervention was not significantly associated with improved maternal coping.73 RCT evidence also reports that regular home-support programmes that last for up to a year made mothers significantly more responsive to their infant and meant that they were able to provide more appropriate and varied stimulations for the infant.67

Evidence from a cohort study where parents were visited regularly and taught care-taking skills, games and exercises reported a significantly better home environment for the family. However, there was no difference found between the intervention group and the control group with regards to maternal coping.74 Evidence from a cohort study also assessed the support and psychological impact of an Infants Apnea Evaluation Programme for infants on home monitors and reported that monitoring itself significantly reduced anxiety. The structured support programme was found by parents to be supportive.75 A similar cohort study introduced a home counselling programme for parents who used home monitoring. Parents were significantly less stressed by the presence of the monitor and by false alarms, and reacted less alarmingly to monitor alarms. Parents in the structured support programme used the monitor less, and mainly during sleeping periods.76 One cohort conducted an educational developmental programme at home twice monthly using a parent's voice tape, baby massage and passive range of motion and exercise. The programme resulted in a significant improvement in parent–infant interaction at 6 months and 12 months after discharge, as well as benefiting the infant.77

Evidence from a cohort study reported that a home-healthcare programme and home-visiting programme significantly improved the home environment of the intervention groups compared with the control groups at 1 month and 12 months.5 However, there were no significant differences between groups with regard to family experiences and parental satisfaction.

Evidence from one cross-sectional study and two case-series studies provide insights into the effect of home-support programmes. Specific to the UK, the community neonatal service was valued positively in providing support and continuity of care for parents who needed a high level of support (eg, experiencing depression and bonding struggles with their infant, infant-sleeping issues and feeding problems).78 One study assessed the impact of an intensive care co-ordinator who provided home visits for providing teaching, guidance and support to parents.79 The study reported that the intensive care co-ordinator made families feel comfortable, offering emotional and practical support, and taught parents the necessary skills for parenting the preterm infant. Another similar study assessed a neonatal integrated home-care programme where neonatal nurses taught specific infant care needs and provided emotional support to parents. Parents reported that the programme helped them to bring their preterm infants home earlier, and provided nurse help, support, instruction and encouragement.80

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to focus on identifying interventions that were effective in supporting, informing and communicating with parents who have had a preterm infant. This study has identified a range of interventions that can produce beneficial outcomes for parents in relation to communication, information and support.

RCT evidence reports that developmental and behavioural care programmes such as COPE and MITP significantly reduce stress and depression in mothers of premature infants, significantly increase mothers' knowledge of her infant's condition and care (COPE), and significantly improve mothers' attitudes and confidence in caring for their infant (MITP). COPE and MITP performed better than other such programmes because they were developed to improve both mother and infant outcomes, whereas other developmental programmes focused more on infant outcomes. Such interactive learning programmes appear to be more successful at reducing the mother's stress and improving the mother's knowledge than stand-alone coaching sessions for parents.

Other RCT evidence reported that skin-to-skin care and baby massage significantly improved the mother–infant interaction and increased the mother's sense of competence in handling their infant. These are inexpensive interventions that can be introduced relatively easily to most NICUs.

Perhaps more controversial RCT evidence reports that recording parents' consultations with their doctors significantly improved the parents' recall of diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of their infant. However, in our growing litigious society, doctors may be reluctant to do this.

Cohort evidence reports the benefits of several interventions including discussions around the infant progress chart, parent-support groups at the neonatal unit and home-support programmes once the infant has been discharged. The non-intervention studies further added to the review by bringing a wider breadth of information around the beneficial experiences of developmental care programmes, educational interventions, preparation for visiting the neonatal unit and interventions to reduce parent's stress that might not have been reported within an RCT design.

Important messages have come through this research, which healthcare professionals and neonatal units should consider. Some neonatal units may have already utilised some of these interventions, but we would urge them to use the results of this systematic review to re-evaluate current practice around parents of premature infants and consider whether unit and professional practice requires adaptation or change. Changing practice can be difficult, and a number of key elements are required, including evidence, an understanding of the context of care and a way of facilitating this evidence into practice.81 We also acknowledge that part of the context is a complex range of workforce issues that limits what neonatal units can achieve, despite their best efforts. The focus on developing patient-centred care within the NHS in the UK also applies to neonatal units and should include parent-focused care as an extension of this concept.82

Many of the interventions that have been identified in this study could be described as being building blocks for a family-centred model of care in the UK setting, which embraces the mother and father or significant others in the medical care of their infant. Such interventions act through establishing key actions and interventions that emphasise the importance of communicating with, supporting and informing the family. Furthermore, our review demonstrated that such family-centred interventions resulted in shorter stays at the neonatal units, less rehospitalisation of preterm infants and better long-term outcome with regards to morbidity in this group of infants.4 This contributes to a strong argument that highlights the potential for family-centred care to be made more cost-effective and more acceptable to parents, and in some cases to offer important clinical benefits.

The scope of this review was very broad, and the searches were therefore developed to be inclusive. This resulted in the search being sensitive, but not specific. Furthermore, this systematic review includes intervention studies and non-intervention studies. It is implicit that the non-interventional studies will bring bias to the evidence base. We have therefore stratified the summary of results into RCTs and non-RCTs, with the non-RCTs being stratified further by study design (ie, cohort, case–control, cross-sectional, etc). It was important to include the non-interventional studies, as much of the literature around parents' views and experiences does not lend itself to the RCT design. Being inclusive of studies benefits the evidence base by bringing together ‘experience’ studies in a systematic way, gaining a greater breadth of perspectives and a deeper understanding of issues from the point of view of those targeted by the interventions.

The Scottish Intercollegiate Group Network grading system used in this review is intended to place greater weight on the quality of evidence, and to emphasise that the body of evidence should be considered as a whole, and not rely on a single study. It is also intended to allow more weight to be given to recommendations supported by the good-quality observational studies where RCTs are not available for practical or ethical reasons, as shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network levels of evidence

| 1++ | High-quality meta-analysis, systamatic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of bias |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analysis, systematic review of RCTs or RCTs with a low risk of bias |

| 1- | Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs or RCTs with a high risk of bias |

| 2++ |

|

| 2+ | Well-conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding, bias or chance, and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2- | Case-control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding, bias or chance, and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal |

| 3 | Non-analytical studies—for example, case series, case reports, qualitative |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

The majority of studies included in this review are from the USA, which may affect the generalisation of interventions in the UK neonatal units, and thus the ability would need to be considered. While this review identified a range of interventions that can help parents, certain groups were under-represented in the study samples, including, among others, minority ethnic groups, individuals from lower social classes and young parents. Further good-quality research within a UK setting and research on under-represented groups of parents at the neonatal units are needed.

Despite the limitations of the evidence base, this systematic review highlights interventions for providing improved support, information and communication to parents of a preterm infant. These interventions are summarised in figure 2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Parents of Premature Babies (POPPY) project was supported by an advisory group whose membership consisted of the following people: Dr C Bennett, Neonatal Consultant, John Radcliffe Hospital NHS Trust, Oxford; Professor P Beresford (Chair), Professor of Perinatal Epidemiology and Director of the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) at the University of Oxford; Professor Debra Bick, Centre for Research in Midwifery and. Childbirth, Thames Valley University; Dr M Redshaw, Social Scientist, NPEU, University of Oxford; Dr Joanna Hawthorne, Pychologist, The Brazelton Centre, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust; Professor N Crichton, Professor of Statistics, South Bank University; Mrs P Goodger, Senior Health Visitor, Oxford; Dr G Gyte, Research Associate, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group; Dr M Harvey, Senior Lecturer, Birmingham City University; Dr Y Richens, Consultant Midwife, University College of London Hospital; and C Pimm, BLISS- the premature baby charity representative. The searches for this review were conducted by P Miller, Senior Information Specialist, Royal College of Physicians, London.

Footnotes

To cite: Brett J, Staniszewska S, Newburn M, et al. A systematic mapping review of effective interventions for communicating with, supporting and providing information to parents of preterm infants. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000023. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000023

Funding: The study was funded by the Big Lottery Fund (grant number: RG/1/01014958), and the collaborating organisations included the Royal College of Nursing Research Institute, University of Warwick, the National Childbirth Trust (NCT), the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU), Univeristy of Oxford, the Warwickshire NCT Pre-term Support Group and BLISS, the premature baby charity.

Ethics approval: Ethics was provided by MREC, South East Ethics Research Unit (ref: 06/MRE 01/6).

Contributors: JB made substantial contributions to the design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of the data, and wrote the first draft of the paper. JB wrote the first amendments to the draft paper and the first draft of responses to the reviewers. SS was the principal investigator of the POPPY study, obtained funding for the study, made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, assisted in the selection of papers and the quality assessment of papers, assisted with the interpretation of the data, assisted in the writing of the first draft of the paper and approved the version for publication. MN was the fund holder, made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, assisted in the interpretation of the data, revised drafts of the paper and approved the version for publication. NJ was the patient representative on this study, made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, assisted in the interpretation of the data, revised drafts of the paper and approved the version for publication. LT was a representative of the National Childbirth Trust and a patient representative. She made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, assisted in the interpretation of the data, revised drafts of the paper and approved the version for publication.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Lau R, Morse C. Experiences of parents with premature infants hospitalised in neonatal intensive care units: a literature review. J Neonatal Nurs 1998;4:23–9 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stjernqvist K. Extremely low birth with infants less than 901g. Impact on the family in the first year. Scand J Public Health 1992; 20:226–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veddovi M, Kerry DI, Gibson F, et al. The relationship between depressive symptoms following premature birth, mothers' coping style, and knowledge of infant development. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2001;19:313–23 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh D, Newburn M. Becoming a Father—Mens' Access to Information and Support about Pregnancy, Birth and Life with a New Baby. London: The National Childbirth Trust, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melnyk BM, Feinstein NF, Alpert-Gillis L, et al. Reducing premature infants' length of stay and improving parents' mental health outcomes with the Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) neonatal intensive care unit program: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1414–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finello KM, Litton KM, de Lemos R, et al. Very low birth weight infants and their families during the first year of life: comparisons of medical outcomes based on after care services. J Perinatol 1998;18:365–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray JE, Safron RB, Davis G, et al. Baby care link: Using the internet and telemedicine to improve care for high risk infants. Pediatrics 2000;106:1318–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison H. The principles for family centred neonatal care. Pediatrics 1993;92:643–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Systematic Reviews: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. University of York, 2008. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/publications.htm [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Sign 50: A Guideline Developer's Handbook. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Als H, Gilkerson L, Duffy FH, et al. A three-center, randomized, controlled trial of individualized developmental care for very low birth weight preterm infants: Medical, neurodevelopmental, parenting, and caregiving effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2003;24:399–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van der Pal S, Macguire C, Cessie S, et al. Parental experiences during the first phase at the neonatal intensive care unit after two developmental care interventions. Acta Paediatrica 2007;96:1611–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wielenga J, Smit B, Unk L. How satisfied are parents supported by nurses with the NIDCAP model of care for their preterm infant? J Nurs Care Qual 2006;21:41–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaaresen PI, Rønning JA, Ulvund SE, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of the effectiveness of an early-intervention program in reducing parenting stress after preterm birth. Pediatrics 2006;118:e9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauh VA, Nurcombe B, Achenbach T, et al. The Mother–Infant Transaction Program. The content and implications of an intervention for the mothers of low-birthweight infants. Clin Perinatol 1990;17:31–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nurcombe B, Howell DC, Rauh VA, et al. An intervention program for mothers of low-birthweight infants: preliminary results. J Am Acad Child Psychiatr 1984;23:319–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sumner G, Spietz A. NCATS Caregiver/Parent-Child Interaction Teaching Manual. Seattle, WA: NCATS Publications, University of Washington, School of Nursing, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browne JV, Talmi A. Family-based intervention to enhance infant–parent relationships in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr Psychol 2005;30:667–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer E, Coll C, Seifer R, et al. Psychological distress in mothers of preterm infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1995;16:412–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glazebrook C, Marlow N, Israel C, et al. Randomised trial of a parenting intervention during neonatal intensive care. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2007:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker-Loewen DL. Effects of short-term interaction coaching with mothers of preterm infants. Infant Ment Health J 1987;8:277–87 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byers JF, Lowman LB, Francis J, et al. A quasi-experimental trial on individualized, developmentally supportive family-centered care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2006;35:105–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawhon G. Facilitation of parenting the premature infant within the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2002;16:71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prentice M, Stainton MC. The effects of developmental care of preterm infants on women's health and family life. Neonat Paediatr Child Health Nurs 2004;7:4–12 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawthorne J. Using the Neonatal Behavioural Assessment Scale to support parent–infant relationships. Infant 2005;1:213–18 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culp RE, Culp AM, Harmon RJ. A tool for educating parents about their premature infants. Birth 1989;16:23–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szajnberg N, Ward MJ, Krauss A, et al. Low birth-weight prematures: preventive intervention and maternal attitude. Child Psychiatr Human Dev 1987;17:152–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall WA, Shearer K, Mogan J, et al. Weighing preterm infants before & after breastfeeding: does it increase maternal confidence and competence? MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2002;27:318–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Mangurten HH, et al. Breastfeeding support services in the neonatal intensive-care unit. J Obstetr Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1993;22:338–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White JC, Smith MM, Lowman DK, et al. Parent support of feeding in the neonatal intensive care unit: perspectives of parents and occupational therapists. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2000;19:111–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elliott S, Reimer C. Postdischarge telephone follow-up program for breastfeeding preterm infants discharged from a special care nursery. Neonat Netw 1998;17:41–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tessier R, Cristo M, Velez S, et al. Kangaroo mother care and the bonding hypothesis. Pediatrics 1998;102:e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai HL, Chen CJ, Peng TC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of music during kangaroo care on maternal state anxiety and preterm infants' responses. Int J Nurs Stud 2006;43:139–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman R, Eidelman AI, Sirota L, et al. Comparison of skin-to-skin (kangaroo) and traditional care: parenting outcomes and preterm infant development. Pediatrics 2002;110:16–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Legault M, Goulet C. Comparison of kangaroo and traditional methods of removing preterm infants from incubators. J Obstetr Gynecol Neonat Nurs 1995;24:501–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Affonso D, Bosque E, Wahlberg V, et al. Reconciliation and healing for mothers through skin-to-skin contact provided in an American tertiary level intensive care nursery. Neonat Netw 1993;12:25–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gale G, Franck L, Lund C. Skin-to-skin (kangaroo) holding of the intubated premature infant. Neonatal Netw 1993;12:49–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferber SG, Feldman R, Kohelet D, et al. Massage therapy facilitates mother–infant interaction in premature infants. Infant Behav Dev 2005;28:74–81 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Remedios CM. Evaluation of massage programme for premature infants. Physiotherapy Singapore 2005;8:4–7 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roman R. Parent-to-parent support initiated in the neonatal intensive care unit. Res Nurs Health 1995;18:385–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preyde M, Ardal F. Effectiveness of a parent ‘buddy’ program for mothers of very preterm infants in a neonatal intensive care unit. CMAJ 2003;168:969–73 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsay JK, Roman L, DeWys M, et al. Creative caring in the NICU: parent-to-parent support. Neonatal Netw 1993;12:37–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson J, Andersen K. Evaluation of a program to promote positive parenting in the neonatal intensive care unit. Neonatal Netw 2001;20:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buarque V, de Carvaiho Lima M, Parry Scott R, et al. The influence of support groups on the family of risk newborns and on neonatal unit workers. J pediatr (Rio J) 2006;82:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurst I. One size does not fit all: Parents evaluation of a support program in the neonatal intensive care nursery. J Perinat Neonat Nurs 2006;20:252–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bracht M, Ardal F, Bot A, et al. Initiation and maintenance of a hospital-based parent group for parents of premature infants: key factors for success. Neonatal Netw 1998;17:33–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dammers J, Harpin V. Parents' meetings in two neonatal units: a way of increasing support for parents. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:863–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jarrett MH. Family matters. Parent partners: a parent-to-parent support program in the NICU part II: program implementation. Pediatr Nurs 1996;22:142–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cobiella CW, Mabe PA, Forehand RL. A comparison of two stress-reduction treatments for mothers of neonates hospitalized in a neonatal intensive care unit. Child Health Care 1990;19:93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jotzo M, Poets CF. Helping parents cope with the trauma of premature birth: an evaluation of a trauma-preventive psychological intervention. Pediatrics 2005;115:915–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macnab AJ, Beckett LY, Park CC, et al. Journal writing as a social support strategy for parents of premature infants: a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns 1998;33:149–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeanah CH, Canger CI, Jones JD. Clinical approaches to traumatized parents: psychotherapy in the intensive-care nursery. Child Psychiatr Hum Dev 1984;14:158–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huckabay LM. The effect on bonding behavior of giving a mother her premature baby's picture. Sch Inq Nurs Pract 1999;13:349–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Griffin T, Kavanaugh K, Soto CF, et al. Parental evaluation of a tour of the neonatal intensive care unit during a high-risk pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1997;26:59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koh T, Butow P, Coorey M, et al. Provision of taped conversations with neonatologists to mothers of babies in intensive care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007;334:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Penticuff JH, Arheart KL. Effectiveness of an intervention to improve parent–professional collaboration in neonatal intensive care. J Perinat Neonat Nurs 2005;19:187–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piecuch RE, Roth RS, Clyman RI, et al. Videophone use improves maternal interest in transported infants. Crit Care Med 1983;11:655–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones L, Woodhouse D, Rowe J. Effective nurse-parent communications: a study of parents perceptions in the NICU environment. Patient Educ Counsel 2007;69:206–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fenwick J, Barclay L, Schmied V. ‘Chatting.’ An importanttool for facilitating mothering in the neonatal nursery. J Adv Nurs 2001;33:583–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Freer Y, Lyon A, Stenson B, et al. BabyLink—improving communication among clinicians and with parents with babies in intensive care. Br J Healthcare Comput Inform Manag 2005;22:34–6 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koh TH, Jarvis C. Promoting effective communication in neonatal intensive care units by audiotaping doctor–parent conversations. Int J Clin Pract 1998;52:27–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown KA, Sauve RS. Evaluation of a caregiver education program: home oxygen therapy for infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonat Nurs 1994;23:429–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costello A, Bracht M, Van Camp K, et al. Parent information binder: individualizing education for parents of preterm infants. Neonatal Netw 1996;15:43–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gannon BA. Caring one day at a time. Neonatal Netw 2000;19:25–32 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drake E. Discharge teaching needs of parents in the NICU. Neonatal Netw 1995;14:49–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kowalski W, Leef K, Mackley L, et al. Communicating with parents of premature infants: how is the informant. J Perinatol 2006;26:44–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barrera ME, Rosenbaum PL, Cunningham CE. Early home intervention with low-birth-weight infants and their parents. Child Dev 1986;57:20–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ortenstrand A, Winbladh B, Nordstrom G, et al. Early discharge of preterm infants followed by domiciliary nursing care: parents' anxiety, assessment of infant health and breastfeeding. [see comment]. Acta Paediatr 2001;90:1190–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Broedsgaard A, Wagner L. How to facilitate parents and their premature infant for the transition home. Int Nurs Rev 2005;52:196–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jonsson L, Fridlund B. Parents' conceptions of participating in a home care programme from NICU: a qualitative analysis. Vard I Norden 2003;23:35–9 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Costello A, Chapman J. Mothers' perceptions of the care-by-parent program prior to hospital discharge of their preterm infants. Neonatal Netw 1998;17:37–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bennett R, Sheridan C. Mothers' perceptions of ‘rooming-in’ on a neonatal intensive care unit. Infant 2005;1:171–4 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spiker D, Ferguson J, Brooks G. Enhancing maternal interactive behavior and child social competence in low birth weight, premature infants. Child Dev 1993;64:754–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ross GS. Home intervention for premature infants of low-income families. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1984;54:263–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leonard BJ, Scott SA, Sootsman J. A home-monitoring program for parents of premature infants: a comparative study of the psychological effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1989;10:92–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kurz H, Neunteufl R, Eichler F, et al. Does professional counseling improve infant home monitoring? Evaluation of an intensive instruction program for families using home monitoring on their babies. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2002;114:801–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Resnick MB, Armstrong S, Carter RL. Developmental intervention program for high-risk premature infants: effects on development and parent-infant interactions. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1988;9:73–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Langley D, Hollis S, MacGregor D. Parents’ perceptions of neonatal services within the community: a postal survey. J Neonat Nurs 1999;5:7–11 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Isaacs PC. Teaching parents with high-risk infants in the home. Patient Couns Health Educ 1980;2:84–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Swanson SC, Naber MM. Neonatal integrated home care: nursing without walls. Neonatal Netw 1997;16:33–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, et al. What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? J Adv Nurs 2004;47:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Staniszewska S. West Meeting the patient partnership agenda: the challenge for health care workers. Int J Qual Health Care 2004;16:3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.