Abstract

Introduction

In order to provide baseline data on genetic testing as a key element of personalised medicine (PM), Canadian physicians were surveyed to determine roles, perceptions and experiences in this area. The survey measured attitudes, practice, observed benefits and impacts, and barriers to adoption.

Methods

A self-administered survey was provided to Canadian oncologists, cardiologists and family physicians and responses were obtained online, by mail or by fax. The survey was designed to be exploratory. Data were compared across specialties and geography.

Results

The overall response rate was 8.3%. Of the respondents, 43%, 30% and 27% were family physicians, cardiologists and oncologists, respectively. A strong majority of respondents agreed that genetic testing and PM can have a positive impact on their practice; however, only 51% agreed that there is sufficient evidence to order such tests. A low percentage of respondents felt that they were sufficiently informed and confident practicing in this area, although many reported that genetic tests they have ordered have benefited their patients. Half of the respondents agreed that genetic tests that would be useful in their practice are not readily available. A lack of practice guidelines, limited provider knowledge and lack of evidence-based clinical information were cited as the main barriers to practice. Differences across provinces were observed for measures relating to access to testing and the state of practice. Differences across specialties were observed for the state of practice, reported benefits and access to testing.

Conclusions

Canadian physicians recognise the benefits of genetic testing and PM; however, they lack the education, information and support needed to practice effectively in this area. Variability in practice and access to testing across specialties and across Canada was observed. These results support a need for national strategies and resources to facilitate physician knowledge, training and practice in PM.

Article summary

Article focus

Canadian physicians' perceptions and experience relating to genetic testing and personalised medicine (PM).

Practice and impact of genetic testing and PM in Canada and across specialties.

Implications for continued adoption of genetic testing and PM in Canada across specialties.

Key messages

Family physicians, cardiologists and oncologists across Canada are practicing PM and recognise its benefits and potential impacts.

Physicians reported a number of barriers to the adoption of PM that are currently affecting medical practice in Canada.

The practice of and access to genetic testing and PM varies across specialties and provinces, which will have an impact on their continued adoption.

Strengths and limitations of this study

First national survey of physicians on this topic

Allows for a baseline measure of practice for comparison in future studies

Medical discipline specific study

Administration of the survey over the period 26 May to 15 September 2010 may have negatively influenced the response rate.

There may have been differences in respondents based on the medium used to complete the survey (electronic vs paper-based).

The topic of genetic testing and personalised medicine may not have been relevant to all physicians who were sent the survey, which may have negatively affected the response rate.

All survey results were based on physicians' self-reports.

The physician contact information was purchased through a third party and some data were incomplete or inaccurate.

Introduction

… for the sweet ones [treatments] do not benefit everyone, nor do the astringent ones, nor are all the patients able to drink the same things… (Hippocrates)

Personalised medicine (PM), the tailoring of medical treatment or prevention to the individual characteristics of each patient, has been enabled by recent advances in molecular biology.1 Research in the ‘-omic’ sciences has resulted in improved understanding of the relationships between genes, proteins and disease, providing more tools for PM2–5 and driving a shift in medical practice.6 Evidence of this ‘shift’ includes a 66% increase in cancer-related genetic testing in Ontario between 2002 and 2008,7 and the facts that 10% of FDA approved drugs include pharmacogenomic information on their labels8 and genetic testing is recommended or required for at least 11 FDA approved drugs9 and for 10 Health Canada approved drugs (based on a review of drug labelling using the Health Canada Drug Product Database). A number of applications of PM based on genetic testing are currently in use.10 Pharmacogenomics, the optimisation of drug therapy based on genetic information, has been applied to improve clinical outcomes or reduce side effects and adverse events.11 12 Targeted therapeutics, used in combination with companion diagnostics, has been particularly successful in improving treatment for cancer.13 14 Finally, PM is being used to assess disease risk, facilitating prevention and early detection.15

As a result of these developments, PM has become an increasingly important topic for physicians, healthcare organisations and the public.16 17 There is widespread debate concerning the intended and unintended consequences of PM for the quality and cost of healthcare; many scientific and medical leaders expect PM to increase the quality of healthcare and reduce overall healthcare costs.13 18 19 A few studies have assessed the adoption of genetic testing and its impact on the role and practice of physicians in Canada.20–24 These studies focused primarily on the adoption of genetic tests for the diagnosis and treatment of cancer within Ontario's healthcare system, and recommended physician education, public education and improved coordination of healthcare delivery and genetic testing services. In order to facilitate medical and continuing professional education in PM in Canada, it is essential to have a baseline understanding of current knowledge, attitudes and practices.

The present pan-Canadian survey of practicing oncologists, cardiologists and family doctors was designed to provide baseline data on genetic testing as a key element of PM in Canada regarding attitudes, state of practice and barriers to adoption. Three specialties were targeted in the survey: cardiologists and oncologists as they experience higher volumes and greater need for personalised genetic testing, and family physicians as they are usually the first point of contact for patients and are often involved in screening for risk of disease.

Methods

Ethics approval was received from IRB Services to survey a sample of Canadian physicians (oncologists, cardiologists and family physicians) regarding their knowledge, training and practice in genetic testing and PM.

Physician contact information was obtained from a third party for 859 oncologists and 1165 cardiologists from across Canada. A weighted sample, based on population, of family physicians (n=2334) from Canadian provinces was randomly selected from contacts with email addresses. The self-administered survey was available in French and English and distributed by mail, fax and email during the period 26 May to 15 September 2010. Respondents submitted their responses online, by mail or by fax. Survey candidates were contacted with up to four reminders to encourage participation. The survey questions related to demographic information, training, practice, knowledge and education in PM based on genetic testing, the nature and extent of practice in this area, and the benefits of PM and barriers to its adoption. Questions were developed based on the authors' knowledge of genetic testing and PM. A draft of the survey questions was developed based on this knowledge and a review of the literature of previous surveys conducted in other jurisdictions.25 26 This draft survey was subsequently reviewed by 11 physicians (five oncologists, three cardiologists and three family physicians) and their feedback was incorporated into the final survey. The survey's design was informed by how new technologies or innovations are adopted in practice and a diffusion of innovations framework was considered.27 The survey solicited physicians' knowledge of, attitudes towards and practice of personalised genetic testing to understand the relative advantages, compatibility, ease of implementation and system response to adoption of personalised genetic testing. This is an initial application of this framework to the Canadian context.

Vovici software28 was used for the online survey administration, allowing for both open-ended and close-ended questions, and menu creation for selection of pre-determined answer options for close-ended questions. All questionnaires were reviewed for completeness. The data entry protocol included separate quality review of each survey against the entered data to ensure accuracy. Survey results were analysed using STATA software v 11.0.29

This study was designed to be exploratory and included analyses based on descriptive statistics and bivariate associations. Inferential analyses were not pursued. Answers to survey questions were compared according to medical specialty and region or province. Fewer responses were received from the Atlantic provinces, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta compared to Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia. Data from the Atlantic provinces (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island) were combined and data from Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta were combined.

Due to the small number of responses for certain questions, results with more than a 5% probability of occurring by chance were excluded. Pearson χ2 test statistics were calculated to determine whether differences according to medical specialty, region or province were statistically significant.

Results

Respondent profile

A total of 363 physicians provided responses to the survey (8.3% overall response rate). Physicians not providing direct patient care (n=16) or not practicing family medicine, cardiology or oncology (n=6) were excluded. Thus, the respondent group retained for the analysis comprised 341 active physicians with an adjusted response rate of 9.7%.

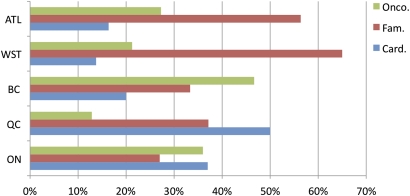

Of the respondents, 43%, 30% and 27% were family physicians, cardiologists and oncologists, respectively. Thirty-three per cent of the respondents practiced in Ontario, 20% in Quebec, 24% in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, 14% in the Atlantic provinces and 9% in British Columbia. Of the cardiologist and oncologist respondents, 73% and 79%, respectively, held academic appointments, compared to 41% of family physician respondents. One-third of survey respondents were in the 46–55 age range. The average time since completion of training was 12 years for participating oncologists, 18 years for cardiologists and 22 years for family physicians. Family physician respondents reported working predominantly in offices or clinics, cardiologists predominantly in academic health science centres, community hospitals and private offices/clinics, and oncologists predominantly in academic health sciences centres. Respondents from all specialties were represented in each geographical area as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of respondents by specialty: family medicine (Fam.), cardiology (Card.) and oncology (Onco.) and by geography: Ontario (ON), Quebec (QC), British Columbia (BC), Western Provinces (WST) and Atlantic provinces (ALT).

Attitudes and perceptions

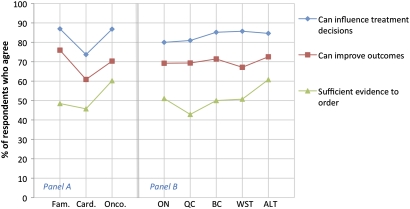

Respondents were asked a series of questions about their attitudes and perceptions regarding the usefulness of genetic testing in the context of PM, as an indicator of physicians' openness to the adoption of PM. The majority of respondents agreed that knowing a patient's genetic profile can influence treatment decision-making (83%) and importantly, can improve patient outcomes (70%). However, only 51% of respondents agreed that there is sufficient evidence to support ordering genetic tests. The perception of the usefulness of genetic testing was similar across specialties and provinces as no significant differences were observed (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Respondent's perceptions of utility by speciality (panel A): family medicine (Fam.), cardiology (Card.) and oncology (Onco.) and by geography (panel B): Ontario (ON), Quebec (QC), British Columbia (BC), Western provinces (WST) and Atlantic provinces (ALT).

State of practice

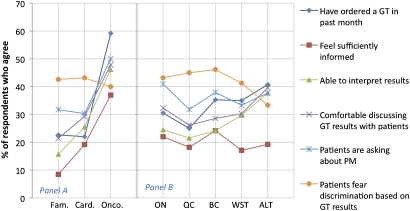

Respondents' current levels of practice and knowledge of genetic testing and PM were also assessed. The results indicate that oncologist respondents are practicing more PM, with 59% reporting having ordered a genetic test in the past month compared to only 22% of general practitioners and cardiologists. Oncologists also reported feeling more informed, more able to interpret test results and more comfortable discussing results with patients compared with other specialties (figure 3). Overall, only 21% of respondents agreed that they are sufficiently informed about PM and 29% agreed that they are able to interpret the results of genetic tests. Thirty per cent of respondents agreed that they are comfortable discussing test results with patients. These measures appear to be consistent across provinces (figure 3). The survey also assessed physicians' perceptions of the impact of genetic testing on their patients. Of the respondents, 40% agreed that their patients have expressed fears of discrimination based on genetic testing and 37% reported that their patients are asking them about genetic testing and PM. Similar reports of patients expressing fear of discrimination were observed across specialties (figure 3); however, more oncologists (50%) reported that patients are asking about PM compared to 30% of cardiologists and 32% of general/family physicians (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Measures of state of practice by specialty (panel A): family medicine (Fam.), cardiology (Card.) and oncology (Onco.) and by geography (panel B): Ontario (ON), Quebec (QC), British Columbia (BC), Western provinces (WST) and Atlantic provinces (ALT). GT, genetic test; PM, personalised medicine.

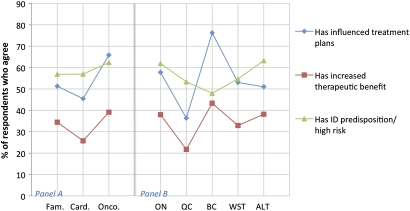

Impacts and benefits

Respondents were asked a series of questions about the impact and benefits of genetic testing for their practices. Most respondents reported that genetic tests they ordered were to identify a genetic predisposition or risk factor (60% agreed vs 20% disagreed) and that these tests influenced patient treatment plans (54% agreed vs 18% disagreed). Many also reported that genetic tests they ordered increased the therapeutic benefit for patients (42% agreed vs 19% disagreed). Comparing across specialties (figure 4, panel A), oncologist respondents were more likely to agree that tests they had ordered had influenced treatment plans (67% agreed) compared to other specialties (χ2 p=0.006). Note that for the purpose of this study, ‘ordering’ means either requisitioning a test directly or facilitating access through another healthcare professional, such as a medical geneticist or other specialist (56% of respondents reported that they are responsible for ordering genetic tests for their patients and 31% reported that a geneticist is responsible for ordering tests for their patients).

Figure 4.

Comparison of reported impacts and benefits by specialty (panel A): family medicine (Fam.), cardiology (Card.) and oncology (Onco.) and by geography (panel B): Ontario (ON), Quebec (QC), British Columbia (BC), Western Provinces (WST) and Atlantic provinces (ALT). ID, identified.

Barriers to adoption

Respondents were asked to indicate what they perceive as the main barriers to their practice of genetic testing and PM. A list of 13 barriers (table 1) was provided. The top five cited barriers were: lack of clinical practice guidelines, limited provider knowledge, attitudes and awareness of benefits, lack of evidence-based clinical information, the cost of testing and a lack of time and resources to educate patients.

Table 1.

Barriers to adoption

| Barriers to physicians ordering genetic tests for personalised medicine | % Of respondents who cited barrier as a ‘main barrier’ |

| Lack of clinical guidelines | 60 |

| Limited provider knowledge, awareness | 57 |

| Lack of evidence-based clinical information | 53 |

| Cost of tests is prohibitive | 48 |

| Lack of time, resources to educate patients | 37 |

| Results take too long for a treatment decision | 33 |

| Too much paperwork/bureaucracy | 31 |

| Lack of insurance coverage | 28 |

| Insufficient regulatory framework | 27 |

| Patient anxiety regarding test results | 24 |

| Lack of reimbursement | 19 |

| Approval process takes too long | 14 |

| Test results will not affect treatment | 13 |

Access to testing

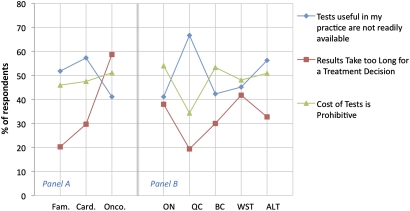

With regards to access to appropriate genetic testing for their patients, 50% of respondents agreed that tests which they believe would be useful in their practice are not readily available, 48% indicated that the cost of genetic tests is a main barrier to the use of PM and 33% indicated that the length of time it takes to obtain results is an important barrier to the use of PM, as the results may not be received in time to help make treatment decisions. Compared to other specialities, oncologists identified the time it takes to obtain results as a barrier to practice (59%) more often than other specialties (figure 5, panel A). In general, these measures relating to access to testing varied across provinces, possibly reflecting differences in access to genetic testing across Canada (figure 5, panel B).

Figure 5.

Measures of barriers to access by speciality (panel A): family medicine (Fam.), cardiology (Card.) and oncology (Onco.) and by geography (panel B): Ontario (ON), Quebec (QC), British Columbia (BC), Western provinces (WST) and Atlantic provinces (ALT).

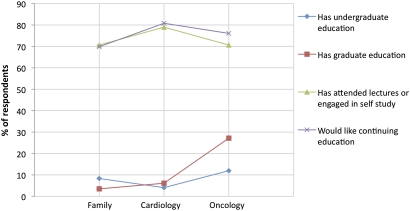

Physician education

Most respondents reported (figure 6) having no formal undergraduate (92%) or graduate training (89%) in genetic testing and PM. Interestingly, 73% of respondents have attended university lectures or engaged in self-study and 75% would like more continuing education in this area. More oncologists reported having graduate training in this area (27%) compared to the other specialties (χ2 p=0.0001).

Figure 6.

Measures of physician education in genetic testing and personalised medicine by speciality.

Discussion

Attitudes, impacts and benefits

The results of this study indicate that Canadian physicians responding to the survey are optimistic about the promise of PM, and open to its use. The majority of respondents agreed that genetic testing as a component of PM can influence treatment plans (83%) and improve outcomes (70%). This is consistent with a recent survey of molecular oncology testing in Ontario, where it was reported that molecular oncology testing is expected to become increasingly prevalent in all areas of diagnosis, prognosis and treatment in the foreseeable future.21 Similar findings from another Canadian survey30 and a study of over 10 000 physicians in the US25 also indicate widespread awareness among physicians of the current value and potential impact of PM. The positive perceptions found among Canadian physician respondents may facilitate efficient and appropriate adoption of PM into practice.

Patient engagement has been identified as a possible factor in physicians' attitudes towards adopting new practices.26 31 Thirty-seven per cent of respondents reported that their patients were enquiring about genetic testing and PM. Physicians also reported that patients expressed fear of discrimination based on genetic testing (figure 3). Although Canadian law does not specifically prohibit genetic discrimination, a level of protection is provided by the Canadian Human Rights Act (Art. 3) and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. Steps have been taken to strengthen these protections. In April 2010, Bill C-508, an act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act to specify genetic discrimination, was introduced into parliament.32 Few respondents indicated that patient anxiety concerning test results is a barrier (table 1). This is consistent with a recent US study of more than 2000 individuals which found no post-test anxiety or adverse outcomes in individuals who received comprehensive genetic profiling.33

State of practice

This study showed that oncologists are practicing more in this area (figures 3 and 4) and are leading in terms of adoption of PM among the specialties surveyed. With regards to access to testing, it was found that this and other measures of the state of practice across the provinces varied (figure 5). This variability in practice and access across Canada may be due to differences in access to testing services, funding and the interpretation of the evidence or perception of benefits from province to province. It has been suggested that decision-making related to predictive genetic testing is ad hoc and variable across Canada and that a coordinated national approach is needed.23 Recommendations have been proposed for a coordinated approach to the adoption and funding of genetic testing in Ontario.34 Work in this area is critical to ensuring equitable access and improving parity of healthcare across Canada. A coordinated strategy and implementation across the country may be challenging given the disparate provincially funded and controlled healthcare systems in Canada.

Barriers to adoption

A lack of medical guidelines was identified by respondents (61%) as the predominant barrier to adoption, indicating a need for the development of best practices and guidelines to support the implementation of PM. Sharing of best practices as well as genetic testing and pharmacoeconomic information across provincial healthcare systems is also likely necessary to support efficient and cost-effective national implementation of PM.

Of the respondents, 62% agreed that medical informatics will be critical to delivering PM. Indeed, vast amounts of data will be generated with widespread adoption, and an IT infrastructure for collection, storage, analysis, interpretation and reporting will be needed.35–37 Furthermore, decision support tools, including electronic medical records, will be needed to facilitate interpretation and point-of-care decision-making. This may pose a significant barrier in Canada where IT infrastructure and electronic medical record implementation is targeted for completion only in 2015,38 significantly later than in other OECD nations.

Surveys of Canadian21 22 and US physicians25 have reported the need for physician education for the successful adoption of PM. These studies found that a majority of physicians lack the education, training and support necessary for successful adoption. The present study supports these findings. Furthermore, respondents indicated that they are actively pursuing more information, with 73% engaging in self-study. These data support a need for formal and continuing physician education in this area. A 2010 survey of 90 medical schools in the US and Canada found that 80% have begun to incorporate pharmacogenomic training into their curricula; however, approximately 60% considered this instruction at their school to be ‘poor’ and more than 80% were not considering increasing the level of instruction within the next 3 years.39

Physicians' perceptions and knowledge of the evidence supporting the clinical and analytical validity of genetic tests for PM are obviously important for its adoption. Canadian and US studies have demonstrated that current physician knowledge, real-world data and guidelines relating to PM have often been insufficient for appropriate adoption,40 even where testing is recommended or publicly funded.41 42 In the present study, 51% of respondents agreed that there is sufficient evidence to order genetic tests for PM. These results suggest either a need for better physician education or a need for additional supporting evidence for PM implementation. Most likely both factors are at play. Further supporting the need for more research was the finding that 53% of respondents cited the need for evidence-based clinical information as a main barrier to their use of genetic testing. Translational research is needed to provide more robust data for evaluating clinical utility and best practices for adoption and implementation within Canada's healthcare system. Furthermore, resources that provide physicians with easy access to accurate and current information would certainly facilitate appropriate and efficient adoption of PM.

Conclusions

In the absence of baseline data on provider knowledge and the practice of PM in Canada, our study fills this important gap by providing a foundation upon which we can build. Canada is lagging behind other jurisdictions which have more resources in place to support PM, including those that facilitate provider and public understanding. PM based on genetic testing is currently being practiced in Canada across specialties and provinces. Many physician respondents recognise its benefits and appear to be open to its adoption. They report that patients are asking them about genetic testing and PM; however, most physician respondents are not confident in discussing genetic testing and PM with their patients. This may not be surprising considering the overall lack of formal education in the field among surveyed physicians, as well as the limited time and resources available for physicians to study this subject. These study results also indicate variability in practice and access to genetic tests across Canada among those surveyed. In addition, the study results point to the need for pan-Canadian strategies and resources that facilitate healthcare provider knowledge, training and practice at the undergraduate and graduate levels, and through targeted continuing professional education interventions.

Soaring healthcare costs across industrialised countries are not sustainable. A few PM pioneers are paving the way towards demonstrating that these new molecular tests may result in better care at lower costs. Indeed, the history of innovation across many industries such as the computer, telecommunications, higher education, transportation and many other sectors has shown that previously inaccessible and expensive products and services can be made more accessible at lower cost.43 Hence, as we strive for better healthcare, PM and the new models required for its full implementation present an unavoidable challenge and perhaps an opportunity to transform our healthcare system into one adapted to the 21st century.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Drs Jean-Claude Tardif, Jean-Michel Turc, Charles Butts and Simon Sutcliffe for their support in survey development and for providing insights into the Canadian personalised medicine landscape, and the analytical support of Alex Kotsopolous, Natalia Lobach and Maureen Hazel.

Footnotes

To cite: Bonter K, Desjardins C, Currier N, et al. Personalised medicine in Canada: a survey of adoption and practice in oncology, cardiology and family medicine. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000110. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000110

Funding: This study was funded by the Centre of Excellence in Personalized Medicine, a federally funded Canadian Centre of Excellence in Commercialisation and Research (CECR).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by Institutional Review Board Services.

Contributions: All authors were involved in designing the survey, interpreting the results and drafting the article. In addition, JP and FDA were involved in the implementation, data collection and analysis. Three co-authors (CD, KB and NC) are employed by Cepmed. JP and FDA were employed by PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, and were commissioned by Cepmed to lead the survey project.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The raw data cannot be shared.

References

- 1.President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST). “Priorities for Personalized Medicine”. http://www.whitehouse.gov/files/documents/ostp/PCAST/pcast_report_v2.pdf (accessed Sep 2008).

- 2.Hudson TJ. Personalized medicine: a transformative approach is needed. CMAJ 2009;180:911–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins FS. Has the revolution arrived? Nature 2010;464:674–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ku CS, Loy EY, Salim A, et al. The discovery of human genetic variations and their use as disease markers: past, present and future. J Hum Genet 2010;55:403–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manolio TA, Brooks LD, Collins FS. A HapMap harvest of insights into the genetics of common disease. J Clin Invest 2008;118:1590–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginsburg GS, Willard HF. Genomic and personalized medicine: foundations and applications. J Lab Clin Med 2009;154:277–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molecular Oncology Task Force Report, Ensuring Access to High Quality Molecular Oncology Laboratory Testing and Clinical Cancer Genetic Services in Ontario. Cancer Care Ontario, 2008. http://www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=31935 (accessed Nov 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to personalized medicine. N Eng J Med 2010;363:301–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. http://www.pharmgkb.org/clinical/index.jsp (accessed Nov 2010).

- 10.Bates S. Progress towards personalized medicine. Drug Discov Today 2010;15:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkelmann BR, Herrington D. Pharmacogenomics-10 years of progress: a cardiovascular perspective. Pharmacogenomics 2010;11:613–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blakey JD, Hall IP. Current progress in pharmacogenetics. J Clin Pharmacol 2011;71:824–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamandis M, White NM, Yousef GM. Personalized medicine: marking a new epoch in cancer patient management. Mol Cancer Res 2010;8:1175–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. Personalized medicine in oncology: a personal view with myths and facts. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2010;5:141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright CF, Kroese M. Evaluation of genetic tests for susceptibility to common complex diseases: why, when and how? Hum Genet 2010;127:125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knoppers BM, Scriver C. Genomics, Health and Society: Emerging Issues for Public Policy. Ottawa: Policy Research Initiative, 2004. http://www.policyresearch.gc.ca/doclib/genomicbook_e.pdf (accessed Nov 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) publication. Pharmacogenetics: Opportunities and Challenges for Health Innovation. Paris: 2009. http://www.oecd.org/document/6/0, 3343, en_2649_34537_39405190_1_1_1_1,00.html (accessed Nov 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis JC, Furstenthal L, Desai AA, et al. The microeconomics of personalized medicine: today's challenge and tomorrow's promise. Nature Rev Drug Discov 2009;8:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allison M. Is personalized medicine finally arriving? Nature Biotechnol 2008;26:509–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metcalfe KA, Fan I, McLaughlin J, et al. Uptake of clinical genetic testing for ovarian cancer in Ontario: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol 2009;112:68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller FA, Krueger P, Christensen RJ, et al. Postal survey of physicians and laboratories: practices and perceptions of molecular oncology testing. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller FA, Carroll JCC, Wilson BJ, et al. The primary care physician role in cancer genetics: a qualitative study of patient experience. Fam Pract 2010;27:563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adair A, Hyde-Lay R, Einsiedel E, et al. Technology assessment and resource allocation for predictive genetic testing: A study of the perspectives of Canadian genetic health care providers. BMC Med Ethics 2009;10:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little J, Potter B, Allanson J, et al. Canada: public health genomics. Public Health Genomics 2009;12:112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.https://www.medcoresearchinstitute.com/community/pharmacogenomics/physicansurvey;jsessionid=14BFD8577F0BC0699643349A4B9F2FFA.node0 (accessed Nov 2010).

- 26.Ohata T, Tsuchiya A, Watanabe M, et al. Physicians' opinion for 'new' genetic testing in Japan. J Hum Genet 2009;54:203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Everett MR. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th edn New York: The Free Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vovici Survey Software. http://www.vovici.com/.

- 29.StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll JC, Cappelli M, Miller F, et al. Genetic services for hereditary breast/ovarian and colorectal cancers - physicians' awareness, use and satisfaction. J Community Genet 2008;11:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamb NE, Myers RM, Gunter C. Education and personalized genomics: deciphering the public's genetic health report. Per Med 2009;6:681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.http://www.ccgf-cceg.ca/sites/default/files/2010-04-14%20-%20Introduction%20of%20BillC-508%20-%20Genetic%20Discrimination.pdf (accessed Nov 2010).

- 33.Bloss CS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Effect of direct-to-consumer genomewide profiling to assess disease risk. N Engl J Med 2011;364:524–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ontario Genetics Secretariat. Genetic Testing, Services and Research, Contributing to the Future Health of Ontarians. White Paper, Toronto, Ontario, Ontario Genetics Secretariat, Toronto, Ontario, Ontario Genetics Secretariat, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fackler JL, McGuire AL. Paving the way to personalized genomic medicine: steps to successful implementation. Curr Pharmacogenomics Person Med 2009;7:125–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawamoto K, Lobach DF, Willard HF, et al. A national clinical decision support infrastructure to enable the widespread and consistent practice of genomic and personalized medicine. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2009;9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Downing GJ. Key aspects of health system change on the path to personalized medicine. Transl Res 2009;154:272–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/flash/lang-en/ar2009-2010/docs/CHI_AnnualReport_2009-2010_ENG.pdf (accessed Nov 2010).

- 39.Green JS, O'Brien TJ, Chiappinelli VA, et al. Pharmacogenomics instruction in US and Canadian medical schools: implications for personalized medicine. Pharmacogenomics 2010;11:1331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellcross CA, Kolor K, Goddard KA, et al. Awareness and utilization of BRCA1/2 testing among U.S. primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu AC, Fuhlbrigge AL. Economic evaluation of pharmacogenetic tests. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;84:272–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips KA, Marshall DA, Haas JS, et al. Clinical practice patterns and cost effectiveness of human epidermal growth receptor 2 testing strategies in breast cancer patients. Cancer 2009;115:5166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christensen C. The Innovator's Prescription: A Disruptive Solution for Health Care. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.