Abstract

Objective

To determine the ideal conditions for use of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) in older outpatients with chronic pulmonary diseases.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Participants

1378 outpatients with chronic pulmonary diseases ≥60 years of age.

Intervention

Participants were educated about PPV23, and those who responded affirmatively were vaccinated between August and November 2002. The participants who chose no intervention served as controls. The prevaccine period was defined as August 2001 to August 2002. Participants were followed for 2 years from December 2002 or until death.

Main outcome measures

Events of interest included the first episode of bacterial (including pneumococcal) pulmonary infection (primary endpoint) and death of any cause (secondary endpoint).

Results

Frequent episodes of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period significantly decreased event-free survival during the 2-year observation period (p<0.001). Chronic respiratory failure was associated with a decreased event-free survival only when the pulmonary infection episode did not occur in the prevaccine period (p<0.001). No significant differences in event-free survival were observed between the vaccinated and unvaccinated group during analysis of the entire cohort. In the Cox proportional hazards regression model, event-free survival decreased significantly when pulmonary infection occurred in the prevaccine period. In the subgroup analysis, the first episode of bacterial pulmonary infection (but not death of any cause) was reduced significantly by PPV23 only in patients with chronic respiratory failure who had no episodes of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period (p=0.019).

Conclusion

The efficacy of PPV23 against pulmonary infection and death of any cause might be unachievable if pulmonary infection occurs during the prevaccine period. PPV23 needs to be given to older patients with chronic pulmonary disease at an earlier time in which infectious complications in the lung have not yet occurred.

Keywords: PPV23, Chronic pulmonary disease, older patient, respiratory infection, epidemiology, clinical pharmacology, statistics and research methods, bmj open, infection control, adult thoracic medicine, infectious diseases

Article summary

Article focus (hypothesis)

The efficacy of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) might be compromised by an episode of pulmonary infection in the prevaccine period or chronic respiratory failure in older patients with chronic pulmonary disease.

Key messages

The PPV23 efficacy might be unachievable if pulmonary infection occurs during the prevaccine period.

The episode of pulmonary infection could be prevented by PPV23 in older patients with non-infectious complications such as chronic respiratory failure.

Older patients with chronic pulmonary disease need to receive the PPV23 vaccination at an earlier time in which infectious complications in the lung have not yet occurred.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Only participants who responded affirmatively received PPV23. They were not assigned randomly to a group.

The diagnosis of pneumococcal pulmonary disease was not made in the majority of patients who had pulmonary infection during the study period. The microbiological diagnosis in the lower respiratory tract, which is not normally sterile, is ambiguous.

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae continues to be one of the main causative pathogens in community-acquired pneumonia and meningitis.1 2 Owing to the high mortality of S pneumoniae infections, especially in older and very young patients, prophylactic use of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) is recommended for people at an increased risk of pneumococcal disease in developed countries.3–7 The efficacy of PPV23, however, remains controversial. Despite the fact that the results of pre and postlicensed trials in immunocompetent people were supportive of regulatory approval of vaccine use, clinical studies in older or young adults with comorbidities in developed countries produced little convincing evidence of effectiveness against a common manifestation of pneumococcal infections such as pneumonia.8–12 A retrospective study conducted in 1999 suggested that PPV23 was associated with significant reductions in hospitalisation and mortalities of older patients with chronic lung disease and contributed to medical-care cost savings, although meta-analytical reviews published thereafter failed to show any statistically significant evidence of the protective effects of PPV23 against the development of pneumonia in older patients with chronic illnesses.13–15

We previously reported a 2-year cohort clinical study of older outpatients with chronic pulmonary disease to investigate the prophylactic effects of PPV23 on bacterial and pneumococcal pulmonary infection onset and outcome.16 Analysis of the comparison between the vaccinated and unvaccinated group showed a decline in the incidence of bacterial pulmonary infection only in the vaccinated group. This result might be associated with PPV23 effectiveness, although detailed background information regarding underlying pulmonary conditions was not provided. A subgroup analysis needs to be carried out, since chronic pulmonary disease includes various clinical and pathophysiological pictures. Underlying pulmonary diseases could cause chronic respiratory failure if repeatedly complicated by lung infections, and such heterogeneity may generate different outcomes after vaccination.17 We decided to reanalyse the data to study the influence of clinical background during the prevaccine period on PPV23 efficacy in older patients with chronic pulmonary disease.

Methods

Study population

All the outpatients ≥60 years of age (a total of 1378 participants at the start of the study) with chronic pulmonary disease in the Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Diseases Centre were included in this study. These patients were informed of the prophylactic effects of PPV23 on infectious pulmonary exacerbations. Chronic pulmonary diseases in this study included bronchial asthma, chronic pulmonary emphysema, old tuberculosis, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, non-tuberculous mycobacteria and others (table 1). Patients who presented with a fever (≥37.5°C) were excluded from the study according to the Preventive Vaccination Law issued by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Once the clinical status of these patients became stable, the patients were invited to participate in the study. Home oxygen therapy (HOT) had been prescribed according to the Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS) Guidelines for 97 participants with chronic respiratory failure upon study initiation (table 1), but no patients were newly prescribed HOT during the observation period.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 1378 outpatients with chronic pulmonary disease

| Frequency of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period |

p Value* | |||

| 0 (n=1164) | 1 (n=167) | >1 (n=43) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Mean±SD | 71.3±7.0 | 73.3±6.9 | 73.0±7.0 | <0.001 |

| Median | 71 | 73 | 73 | |

| Male | 626 (53.8%) | 98 (58.7%) | 27 (62.8%) | 0.272 |

| Female | 538 (46.2%) | 69 (41.3%) | 16 (37.2%) | |

| Chronic respiratory disease† | ||||

| Bronchial asthma | 517 | 59 | 16 | |

| Chronic pulmonary emphysema | 197 | 40 | 14 | |

| Old tuberculosis | 157 | 33 | 10 | |

| Chronic bronchitis | 106 | 18 | 5 | |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 100 | 9 | 0 | |

| Non-tuberculous mycobacteria | 84 | 10 | 2 | |

| Bronchioectasis | 31 | 13 | 5 | |

| Others | 103 | 15 | 4 | |

| Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23-vaccinated | 512 (44.0%) | 109 (65.3%) | 25 (58.1%) | <0.001 |

| Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23-unvaccinated | 652 (56.0%) | 58 (34.7%) | 18 (41.9%) | |

| Chronic respiratory failure | ||||

| + | 70 (6.0%) | 20 (12.0%) | 7 (16.3%) | <0.001 |

| − | 1094 (94.0%) | 147 (88.0%) | 36 (83.7%) | |

Data were analysed using the Wilcoxon test or Pearson test.

Some patients were diagnosed as having more than one chronic respiratory disease.

Study design

We did not adopt a randomised controlled study design, since the PPV23 vaccination is considered a part of standard care in many developed countries. Additionally, some older participants with chronic pulmonary disease were in an immunocompromised status; therefore, a randomised controlled study of vaccine effectiveness may violate ethical principles and human rights. Written informed consent forms were obtained from all participants. To avoid selection bias, doctors and other medical staff were not allowed to assign patients to the vaccine or non-vaccine group; instead, individual patients decided whether or not to be vaccinated. The same form, which included an explanation of the study, was provided to all the participants. A total of 647 patients were injected with PPV23 (Pneumovax, Merck, Rahway, New Jersey) intramuscularly into their non-dominant upper arm between August and November 2002. The prevaccine period was defined as 1 year prior to PPV23 vaccination (August 2001 to July 2002).

Data collection

Participants were followed from December 2002 to the end of the study in November 2004 (for 2 years) or until death in the clinic approximately every 2 months as long as the clinical status remained stable. A diagnosis of pulmonary infection was made by respiratory physicians according to the Japanese Respiratory Society Guidelines for the Management of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults. In brief, pulmonary infection was suspected if more than two of the following criteria were met: temperature ≥37.0°C, white-blood-cell count >8000/mm3 and C-reactive protein >0.7 mg/dl. A diagnosis of pneumonia was made when chest radiographs revealed alveolar opacities. If a cough with yellow sputum production was observed in the absence of the alveolar opacities on the chest radiograph, the patients were diagnosed as having acute bronchitis or exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. It was very difficult to distinguish pneumonia clearly from acute bronchitis or an acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis in some patients, since there were considerable clinical overlaps between these illnesses including the symptoms, blood test results, causative pathogens and antibiotic treatment. Hence, pulmonary infection was expressed as a dichotomous variable.

A diagnosis of pneumococcal pulmonary infection was made if S pneumoniae was the dominant organism stained with Gram stain in the sputum smear or if the sputum culture was positive (>107 colony forming units/ml). When S pneumoniae was not identified, patients were diagnosed as having a pulmonary infection caused by an identified pathogen or with a bacterial pulmonary infection if no possible causative pathogen was detected but if the clinical data were highly suggestive of bacterial infection in the lung. Empirical antibiotic therapy was started in all the patients promptly once clinical data sufficient to satisfy the definition of pulmonary infection were obtained. The initial treatment was replaced by second-line therapy of antibiotics chosen according to the sensitivity results.

Event of interest

We hypothesised that repeated pulmonary infection and concomitant gradual loss of lung function might be related to a reduced PPV23 efficacy. Participants were grouped based on these factors: frequency of infectious (including pneumococcal) pulmonary infection episode within 1 year prior to the PPV23 vaccination (0 episodes, 1 episode and >1 episode) and chronic respiratory failure represented by HOT usage. Events of interest included the first episode of bacterial or pneumococcal pulmonary infection (pneumonia, acute bronchitis or exacerbation of chronic bronchitis) where antibiotic treatment was required (primary endpoint) and death of any cause (secondary endpoint). The case of death with missing values was not counted as an event of interest but was included in the mortality.

Statistical analysis

Differences in event-free survival were depicted with Kaplan–Meier curves, and the logrank test was applied for analysis. The primary and secondary endpoints (the first episode of pulmonary infection and death of any cause, respectively) were analysed separately. Cross-tabulated data were compared by the Wilcoxon test or the Pearson χ2 test. Relative risks for the events were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. The covariates used in the analysis were: (1) pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period, (2) chronic respiratory failure and (3) PPV23 vaccination. For further analysis, gender and age were added as covariates, and the data were analysed. No other variables were regarded as covariates in relation to event-free survival. Predictive Analytics Software statistics 18 and SAS software were used for the statistical analysis.

Results

Participant characteristics are shown in table 1. Significant reductions in vaccination rate, age and frequency of chronic respiratory failure were observed in the group without pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period compared with the other two groups with at least one episode of infectious lung complications. No significant gender difference was seen among groups.

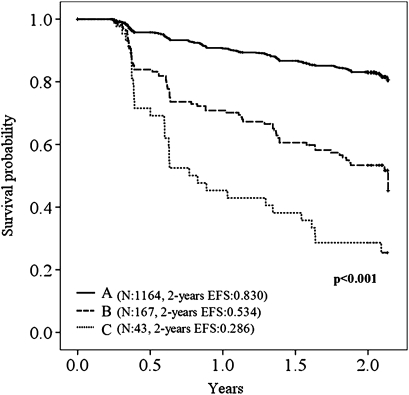

The effects of underlying pulmonary conditions on event occurrences were analysed before PPV23 effectiveness was evaluated. Event-free survival in the Kaplan–Meier method dropped significantly as the frequency of pulmonary infection in the prevaccine period increased: the first episode of pulmonary infection (figure 1); death of any cause (supplemental figure A). Chronic respiratory failure was associated with a significant decrease in event-free survival only in the absence of pulmonary infection in the prevaccine period: the first episode of pulmonary infection (supplemental figure B, table 2); death of any cause (supplemental figure C, supplemental table A).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing the proportion of patients free of the first episode of pulmonary infection during the observation period. Frequency of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period: (A) zero episodes; (B) one episode; (C) more than one episode. EFS, event-free survival.

Table 2.

Effects of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period and chronic respiratory failure on pulmonary infection-free survival after pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 vaccination

| Frequency of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period | Chronic respiratory failure | N | Event* | Pulmonary infection-free survival at the end of the study* | 95% CI | p Value† |

| 0 | (−) | 1094 | 154 | 0.840 | 0.816 to 0.864 | <0.001 |

| 0 | (+) | 70 | 19 | 0.653 | 0.525 to 0.781 | |

| 1 | (−) | 147 | 59 | 0.550 | 0.462 to 0.638 | 0.506 |

| 1 | (+) | 20 | 10 | 0.409 | 0.168 to 0.649 | |

| >1 | (−) | 36 | 25 | 0.315 | 0.161 to 0.469 | 0.348 |

| >1 | (+) | 7 | 6 | 0.143 | 0.000 to 0.402 |

Event represented the number of patients who were diagnosed as having pulmonary infection during the observation period.

Data were analysed using the logrank test.

Participants were not randomly assigned to groups; vaccination was chosen or declined by each individual. As a result, the number of vaccinated patients was significantly higher than the number of unvaccinated patients when pulmonary infection occurred during the prevaccine period (table 1). No significant PPV23 effectiveness against the development of first episode of pulmonary infection during the observation period was seen between the vaccinated and unvaccinated group in the Kaplan–Meier method (supplemental figure D). The mortality was, however, significantly high in the vaccinated group (supplemental figure E). This result may be misleading owing to the vaccination imbalance among groups. In the Cox proportional hazards regression model applied for covariate adjustment, no hazardous effects of PPV23 on the incidence or timing of the first episode of pulmonary infection or death of any cause were observed. The HR for the first episode of pulmonary infection or death of any cause increased significantly owing to some covariates such as pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period and chronic respiratory failure. Other covariates including gender and age were not associated with the first episode of pulmonary infection but were associated with death of any cause (table 3). The cause of death (n=85) among all the participants during the observation period is shown in supplemental table B.

Table 3.

Association of the frequency of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period, chronic respiratory failure, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23, gender and age with the first episode of pulmonary infection or death of any cause

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Covariates for the risk of the first episode of pulmonary infection | ||

| Pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period | ||

| 1 episode | 3.251* (2.436 to 4.338) | <0.001 |

| >1 episode | 6.480* (4.380 to 9.589) | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 1.767 (1.227 to 2.546) | 0.002 |

| Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 vaccination | 1.096 (0.848 to 1.416) | 0.396 |

| Gender | 0.911 (0.712 to 1.166) | 0.457 |

| Age | 0.994 (0.976 to 1.013) | 0.553 |

| Covariates for the risk of death of any cause | ||

| Pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period | ||

| 1 episode | 2.289* (1.380 to 3.797) | 0.001 |

| >1 episode | 3.134* (1.486 to 6.612) | 0.003 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 2.152 (1.234 to 3.752) | 0.007 |

| Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 vaccination | 0.795 (0.499 to 1.264) | 0.332 |

| Gender | 0.340 (0.199 to 0.580) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.040 (1.008 to 1.072) | 0.014 |

HR was estimated in relation to the case of outpatients with no episode of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period.

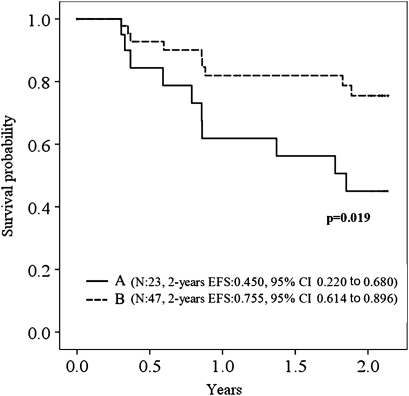

A subgroup analysis was performed to find the ideal condition for PPV23 use in older patients with chronic pulmonary disease. There are no significant differences in pulmonary infection-free survival between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients when grouped only by frequency of pulmonary infection in the prevaccine period (not shown). Pulmonary infection-free survival was somewhat improved when patients with chronic respiratory failure were vaccinated (p=0.078). This effectiveness became significant when patients who had at least one episode of pulmonary infection in the prevaccine period were excluded (figure 2, table 4). The mortality was not reduced by PPV23 in patients with chronic respiratory failure who had no episodes of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period (supplemental figure F). The cause of death (n=9) among patients with chronic respiratory failure who had no episodes of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period was as follows: chronic respiratory failure, two; cerebrovascular disease, two; and unknown, one in vaccinated patients and chronic respiratory failure, two; lung cancer, one; and unknown, one in unvaccinated patients. In this group, PPV23 was shown to have an effect on the first episode of pulmonary infection, but it did not reduce the number of deaths owing to any cause.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing the proportion of patients free of the first episode of pulmonary infection during the observation period. Patients with chronic respiratory failure who had no episodes of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period: (A) unvaccinated; (B) vaccinated. EFS, event-free survival.

Table 4.

Influence of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period and chronic respiratory failure on the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 vaccine efficacy

| Frequency of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period | Chronic respiratory failure | Vaccinated* | Unvaccinated* | p Value† |

| (−) | (−) | 0.846 (465) | 0.836 (629) | 0.931 |

| (+) | 0.755 (47) | 0.450 (23) | 0.019 | |

| 1 episode | (−) | 0.557 (92) | 0.490 (55) | 0.665 |

| (+) | 0.431 (17) | 0.333 (3) | 0.876 | |

| >1 episode | (−) | 0.317 (22) | 0.214 (13) | 0.200 |

| (+) | 0.000 (3) | 0.250 (4) | 0.093 |

Data represented the pulmonary infection-free survival (%) at the end of the study (2 years after pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 vaccination). Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of patients.

Data were analysed using the logrank test.

There were only 29 pneumococcal pulmonary infection during the observation period (pneumococcal pulmonary infection, 22; death, seven; supplemental table C). The pneumococcal pneumonia-free survival decreased significantly in the presence of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period (p<0.001; supplemental figure G). No effects of chronic respiratory failure on pneumococcal pneumonia-free survival were observed (p=0.196). PPV23 vaccination did not show any significant protective effects against the development of pneumococcal pneumonia (supplemental figure H).

Discussion

The effects of the PPV23 vaccination on older patients with chronic pulmonary disease varied in accordance with the frequency of lung-infection episodes and the presence of chronic respiratory failure during the prevaccine period. Our findings suggest the following: PPV23 vaccination might work effectively unless previous lung-infection episodes had occurred, and a subgroup analysis of the underlying disease associated with pneumococcal complications might be useful for finding the possible ideal conditions for PPV23 use. To our knowledge, this is the first report to characterise PPV23 effectiveness owing to the heterogeneity of underlying lung conditions such as the presence of pulmonary-infection episodes prior to vaccination or chronic pulmonary failure in older patients with chronic pulmonary disease.

Comparison with other studies

Previous pulmonary infection was highly associated with poor clinical prognosis. This finding suggests that beneficial PPV23 effectiveness might be unachievable for older people with chronic pulmonary disease in the presence of infectious complications during the prevaccine period. In a multicentre, double-blind controlled study conducted in Sweden, PPV23 was not efficacious against overall pneumonia in middle-aged or older non-immunocompromised individuals who had been treated for community-acquired pneumonia.18 In that study, the survival rate calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method was still >80% in both vaccinated and unvaccinated populations after a 2-year observation, while our results showed that the survival rate was <60% if episodes of pulmonary infection had occurred within 1 year prior to vaccination. These results are consistent with previous suggestions that chronic pulmonary disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a risk factor for repeated pneumonia and that protective effects of PPV23 could not be obtained.19–21 Conflicting results were shown in some other reports in which the beneficial effects of PPV23 in patients with COPD were indicated, although previous episodes of pneumonia prior to vaccination were not considered, and participants were not limited to older people.13 22 Alfageme et al showed PPV23 effectiveness in patients <65 years of age with COPD in a randomised controlled study in 596 patients.23 These results and data indicate that PPV23 might be inefficacious in the older population with chronic pulmonary disease, especially when complicated by lung infection prior to the vaccination. Despite the strong evidence of PPV23 efficacy against invasive pneumococcal disease, altered immune response, disruption of a physical barrier in the airways owing to progressive chronic pulmonary disease and repeated pulmonary infection could compromise the benefits.1 24 PPV23 vaccination should be given to patients with chronic pulmonary disease at an earlier stage in which infectious complications have not yet occurred.

The probability of survival was significantly increased by PPV23 in the presence of chronic respiratory failure in patients without any episodes of pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period. The pulmonary infection-free survival rate was 75.5% at the end of the observation period when PPV23 was given. Without PPV23, survival was reduced to 45.0%, almost the same level as that in the case where infectious lung complications had occurred during the prevaccine period. This result indicates that pulmonary infection owing to chronic respiratory failure could be prevented by the PPV23 vaccination. Oxygen therapy and inhalation therapy containing corticosteroids may be administered in COPD patients when airflow is severe, and chronic respiratory failure is present, but these treatments were suggested to be risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia.25–27 Additionally, bacterial colonisation of the distal airway may occur owing to the altered pulmonary defence.24 We suggest that patients receive the PPV23 vaccination soon after the diagnosis of chronic respiratory disease such as COPD, especially when maintenance treatments for impaired lung function are expected to be risk factors for pneumonia. In this study, the number of participants with chronic respiratory failure who were free of lung infections during the prevaccine period was only 70. Thus, a large-scale study is warranted.

Strengths and limitations of the study

When informed consent was obtained prior to the study initiation, PPV23 vaccine recommendations were made, and only participants who responded affirmatively received the vaccination. This method may be associated with these results: the vaccination rate increased significantly in high-risk patients who had at least one episode of bacterial pulmonary infection during the prevaccine period or chronic respiratory failure, and the mortality was higher in vaccinated patients, although the presence of adverse effects of PPV23 is unlikely because PPV23 had generally been considered safe based on clinical experience since 1977.7 In the Cox proportional hazards model, PPV23 was not a risk factor for the events. All of the participants in this study were older patients with chronic pulmonary disease, and all of them could be categorised into groups for which PPV23 vaccination is recommended in the USA and some European countries.3 7 14 In Japan, no vaccine recommendations against pneumococcal infection are issued by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.11 Japanese participants need to accept some risks for the public benefit, and not for their own, if selected for the unvaccinated group. This condition is different from that in some developed countries where unvaccinated control subjects in clinical trials of the PPV23 vaccine could still be protected by previous vaccination and indirect immunity from other people, including children.28–30 Pneumococcal infection was associated with increasing mortalities, while the beneficial effects of PPV23 without any severe adverse events were suggested in some previous clinical trials.1 8 15 31 32 Therefore, we decided to conduct a non-randomised clinical study to ensure that participants were treated with respect and dignity.

The doctors had access to the patients' vaccination record during the observation period. However, at the time of this study, PPV23 had already been approved by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and there were no conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical companies. All the treatments were supported by the public healthcare system funded by the Japanese government; no specific grants were provided from any funding agencies. Diagnosis of pulmonary infection was made according to the same diagnostic criteria. Therefore, it is unlikely that treatment bias occurred during the observation period.

The diagnosis of pneumococcal disease was not made in the majority of patients who had pulmonary infections during the observation period. Identification of S pneumoniae using a sputum Gram stain is required for definitive diagnosis. However, compared with invasive pneumococcal disease defined as any condition in which S pneumonia is identified in a normally sterile body site, microbiological diagnosis in the lower respiratory tract is ambiguous.1 5 It was noted by many authors that respiratory secretion samples for pneumococcal identification might be unreliable owing to the technical difficulties in obtaining good-quality sputum and in distinguishing causative specimens from colonisation.21 The positive results in urine antigen testing might be related to previous infection or colonisation.33 It might be difficult to assess PPV23 effectiveness on pneumococcal pulmonary infection using these procedures. Blood cultures are recommended for patients hospitalised after a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia, although its cost-effectiveness has been questioned in several studies.34 Less expensive, novel techniques for accurate diagnosis of pneumonia need to be developed.

Conclusions and policy implications

These data demonstrated that the beneficial effects of the PPV23 vaccination may not be obtainable if an episode of pulmonary infection occurred during the prevaccine period in older patients with chronic pulmonary disease. We suggest that PPV23 needs to be given soon after chronic pulmonary disease is diagnosed. In developed countries, including Japan, older populations with chronic pulmonary disease are growing in number. The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare should introduce the PPV23 vaccination for patients with chronic pulmonary disease and in routine vaccination of children along with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine that could provide indirect beneficial effects to the population in whom PPV23 efficacy may not be expected.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The material (clinical data) that had been used in the study by Watanuki et al16 has been modified and printed with the permission of the European Respiratory Society.

Footnotes

To cite: Inoue S, Watanuki Y, Kaneko T, et al. Heterogeneity of the efficacy of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine caused by various underlying conditions of chronic pulmonary disease in older patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000105. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000105

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board in the Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Diseases Centre.

Contributors: SI was responsible for interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript. YW was responsible for study design, collection and interpretation of the data. YW also revised the drafted manuscript. TK and SM provided statistical support including analysis of the data and training in the use of statistical software. TK and SM also drafted the statistical analysis part in the manuscript and revised the drafted manuscript. TS, NM, TK and YI helped to interpret the findings and contributed to critical revision of the drafted manuscript, particularly regarding pulmonary infection issues. YN and SM helped to interpret the data, provided very useful suggestions regarding immunisation and public health policy, and revised the drafted manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data set used in this manuscript is available from the corresponding author. Approval may be required from the Institutional Review Board in Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Diseases Centre and Yokohama City University Hospital.

References

- 1.Moberley S, Holden J, Tantham DP, et al. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(1):CD000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heather E, Hsu MPH, Kathleen A, et al. Effects of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on pneumococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med 2009;360:244–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC Updated recommendations for prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease among adults using the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). MMWR Morb Motal Wkly Rep 2010;59:34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vila-Corcoles A, Ochoa-Gondar O, Guzman JA, et al. Effectiveness of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in people 60 years or older. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2008;83:373–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith FE, Mann JM. Pneumococcal pneumonia: experience in a community hospital. West J Med 1982;136:1–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC Prevention of pneumococcal disease: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 1997;46:1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson LA, Neuzil KM, Yu O, et al. Effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1747–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews R, Moberley SA. The controversy of the efficacy of pneumococcal vaccine. Can Med Assoc J 2009;180:18–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:2666–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maruyama T, Taguchi O, Niederman MS, et al. Efficacy of 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine in preventing pneumonia and improving survival in nursing home residents: double-blind, randomized and placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedersen RH, Lohse N, Ostergaard L, et al. The effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in HIV-infected adults: a systematic review. HIV Med 2011;12:323–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nichol KL, Backen L, Wuorenma J, et al. The health and economic benefits associated with pneumococcal vaccination of elderly persons with chronic lung disease. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2437–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huss A, Scott P, Stuck AE, et al. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults: meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J 2009;180:48–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Lipsky BA. Are the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccineses effective? Meta-analysis of the prospective trials. BMC Fam Pract 2000;1:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanuki Y, Miyazawa N, Kudo M, et al. Effects of pneumococcal vaccine in patients with chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir Rev 2008;17:43–5 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molinos L, Clemente MG, Miranda B, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in patients with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect 2009;58:417–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortqvist A, Hedlund J, Burman LA, et al. Randomised trial of 23-valemt pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine in prevention of pneumonia in middle-aged and elderly people. Lancet 1998;351:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leech JA, Gervais A, Ruben FL. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccine in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Med Assoc J 1987;136:361–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis AL, Aranda CP, Schiffman G, et al. Pneumococcal infection and immunologic response to pneumococcal vaccine in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 1987;92:204–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams JH, Moser KM. Pneumococcal vaccine and patients with chronic lung disease. Ann Intern Med 1986;104:106–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee TA, Weaver FM, Weiss KB. Impact of pneumococcal vaccination on pneumonia rates in patients with COPD and asthma. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:62–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alfageme I, Vazquez R, Reyes N, et al. Clinical efficacy of anti-pneumococcal vaccination in patients with COPD. Thorax 2006;61:189–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cabello H, Torres A, Ceils R, et al. Bacterial colonization of distal airways in healthy subjects and chronic lung disease: a bronchoscopic study. Eur Respir J 1997;10:1137–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rees PJ. Review: inhaled corticosteroid do not reduce mortality but increase pneumonia in COPD. Evid Based Med 2009;14:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welte T. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of pneumonia. Lancet 2009;374:668–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Serra-Prat M, et al. New evidence of risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based study. Eur Respir J 2008;31:1274–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lexau CA, Lynfield R, Danila R. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among older adults in the era of pediatric pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA 2005;294:2043–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith KJ, Zimmerman RK, Lin CJ, et al. Alternative strategies for adult pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Vaccine 2008;26:1420–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musher DM. Pneumococcal vaccine—Direct and indirect (herd) effects. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1522–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews A, Nadjim B, Gant V, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2003;9:175–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to indentify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andreo F, Ruiz-Manzano J, Prat C, et al. Utility of pneumococcal urinary antigen detection in diagnosing exacerbations in COPD patients. Respir Med 2010;104:397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waterer GW, Jennings G, Wunderink RG. The impact of blood cultures on antibiotic therapy in pneumococcal pneumonia. Chest 1999;116:1278–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.