Abstract

Objectives

Knowledge of a study population's similarity to the target population allows researchers to assess the generalisability of their results. Often generalisability is assessed through a comparison of baseline characteristics between individuals who did and did not respond to an invitation to participate in a study. In this prospective population-based cohort, we broadened this assessment by comparing participants with all individuals from a chronic disease register who satisfied the study eligibility criteria but for a number of reasons, such as the absence of consent to be approached for research purposes, did not participate.

Methods

Data are from the Living with Diabetes Study, a population-based cohort of individuals diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, which commenced in Queensland, Australia in 2008. Individuals were sampled from a federally-funded diabetes register. We compared the characteristics of 3951 study participants with 10 488 non-participants (individuals who were invited to participate but declined) and with 129 900 non-study individuals on the register who did not participate in the study.

Results

Study participants were more likely than non-study registrants to be male, aged 50–69, have type 2 diabetes non-insulin requiring, be recently registered and be non-indigenous Australians. Study participants were more likely than non-participants to be aged 50–69, have type 1 diabetes and be non-indigenous Australians.

Conclusions

The interpretation of a study's generalisability can alter depending on which non-participating group is compared with participants. When assessing generalisability, participants should be compared with the largest possible group of non-participating individuals. When sampling from a disease register, researchers should be wary of the influence of research consent procedures on the register's coverage.

Article summary

Article focus

To assess the similarity between study participants sampled from a chronic disease register and registrants who did not participate in the study.

To assess whether the differences between participants and registrants who did not participate are similar to the differences between participants and individuals who were invited to participate but declined.

Key messages

The generalisability of a study should be assessed by comparing participants with the largest possible group of non-participating individuals.

When sampling from a disease register, researchers should be wary of the influence of research consent procedures on the register's coverage.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Information is available for all individuals registered with the chronic disease register.

The chronic disease register from which study participants were recruited has high coverage of the target population.

Only aggregated data were available for registrants who were not invited to participate in the study.

Introduction

Population-based cohort studies are essential when studying chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, as they can offer a comprehensive understanding of disease trajectory over time and allow for multiple subgroup analyses.1 2 However, the utility of each study's findings depends on whether the results are sufficiently generalisable to the population under investigation. The extent of a study's generalisability, or external validity, depends on how representative of the target population the study's participants are.3–5 Since information on the target population is often unavailable, investigations concerning the generalisability of population-based cohorts, including those concerning diabetes, have focused on the comparison of baseline characteristics between study participants and non-participants to assess how similar or different they are.6–9 However, a high degree of similarity between participants and non-participants does not necessarily mean results arising from the study will have good generalisability, as these two groups as a whole might not fully represent the target population due to coverage error.10 11 The extent to which findings are generalisable can be assessed by comparing the study participants with the largest possible subset of all diseased individuals in the population being studied, other than participants.12 13 The characteristics of this larger group can be accessed through databases such as national chronic disease registers.6

Chronic disease registries are increasingly used to recruit participants to cohort studies. One purported advantage of this is to ensure generalisability to the target population.14–16 In recent years, however, legislative reform concerning privacy issues has been introduced in many countries, including Australia, which has restricted research related access to these databases without an individual's consent.17 It is possible that this may seriously limit the usefulness of chronic disease registers for epidemiological research.18 19 This study investigates the generalisability of one Australian register, the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) and explores whether chronic disease registrants who agreed to participate in a research study have similar characteristics to registrants who satisfied the inclusion criteria but did not participate. We also compare the characteristics of participants with the characteristics of individuals who were invited to participate but declined.

Methods

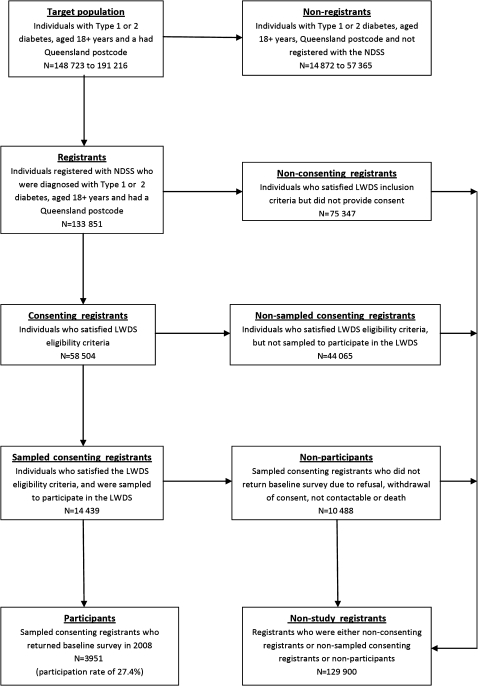

The Living with Diabetes Study (LWDS) is a population-based cohort study that began in Queensland, Australia in 2008. An individual was eligible to participate in the study if they had doctor diagnosed type 1 or 2 diabetes, were aged at least 18 years and had a valid Queensland postal address. Individuals were randomly sampled from a federally-funded register of Australians with diabetes, the NDSS, managed by a non-governmental organisation called Diabetes Australia. The NDSS's coverage of Queenslanders with diabetes is estimated to be between 80% and 90%.20 Since 2001, individuals joining the NDSS have been asked whether they would like to be informed about opportunities to participate in research. Only those who consented to be contacted for research purposes were eligible to be invited to participate in the LWDS. The LWDS sampling design specified three target locations of policy interest to be oversampled: an outer metropolitan area, a new suburban development and a coastal agricultural community. All eligible individuals from the three locations were invited to participate; approximately one in six eligible individuals from the rest of Queensland were invited to participate.

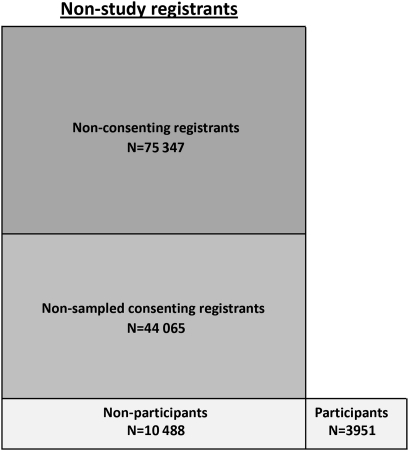

Selected individuals were invited to participate in the LWDS via a mailed questionnaire. Information was collected on demographic and socio-economic characteristics, health behaviour, and health and psychological status. Strategies to maximise participation included reminder cards, telephone calls and replacement surveys. We categorised registrants into four mutually exclusive groups: participants, non-participants, non-sampled consenting registrants and non-consenting registrants. A participant was defined as an individual who agreed to participate in the LWDS. A non-participant was defined as an individual who was invited to participate in the LWDS but declined. A non-sampled consenting registrant was defined as an individual who agreed to participate in the LWDS but was not selected during the sampling process. A non-consenting registrant was defined as an individual who had not agreed to be contacted for research purposes. Initially, participants were compared to non-participants (the reference group). For a secondary comparative analysis, the reference group was expanded to comprise all registrants who were not study participants. This expanded reference group was defined as non-study registrants (figure 1). Available individual-level information on participants and non-participants consisted of sex, age, diabetes status, year of NDSS registration, postcode and indigenous status. Postcodes were matched to the Australian Bureau of Statistics' index of relative socio-economic disadvantage (Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas, SEIFA) ranking, and categorised into tertiles.21 Due to privacy and research consent issues, only covariate aggregate data were available for individuals not invited to participate in the study. Ethics approval was obtained from The University of Queensland's Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee.

Figure 1.

Living with Diabetes Study registrants categorised by participation status.

Data analysis

For participants, non-participants and non-study registrants, we calculated the frequency (percentage) of individuals in each category for sex, age (18–49, 50–69, 70+ years), diabetes status (type 2 non-insulin requiring; type 2 insulin requiring, type 1), registration year (2001–2003, 2004–2005, 2006–2008), SEIFA tertile and indigenous status. Initially, we used logistic regression analyses to compare participants with non-participants on a univariable basis. We then fitted a series of multivariate logistic regression models in order to investigate the impact of potential confounders and obtain fully adjusted associations. Analyses were weighted according to the sampling scheme. As individual-level data were not available for all individuals in the reference group of non-study registrants, we used univariable logistic regression with aggregate data to compare participants with non-study registrants. Results for each of the analyses are presented in table 1 as ORs and 95% CIs.

Table 1.

Comparison between living with diabetes participants, non-participants and non-study registrants

| Participants | Non-participants | Non-study registrants | Participants versus non-participants |

Participants versus non-study registrants | ||

| N=3951 | N=10 488 | N=129 900 | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | Crude OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 2176 (55.1%) | 5885 (56.1%) | 68 618 (52.8%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1775 (44.9%) | 4603 (43.9%) | 61 282 (47.2%) | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.10) | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.17) | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.97) |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–49 | 618 (15.6%) | 246 (21.4%) | 21 387 (16.5%) | 0.67 (0.60 to 0.75) | 0.63 (0.55 to 0.71) | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.79) |

| 50–69 | 2375 (60.1%) | 5649 (53.9%) | 58 988 (45.4%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70+ | 958 (24.3%) | 2593 (24.7%) | 49 525 (38.1%) | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.97) | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.99) | 0.48 (0.45 to 0.52) |

| Diabetes status | ||||||

| Type 2, no insulin | 3023 (76.5%) | 8024 (76.5%) | 82 717 (63.7%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Type 2, insulin | 738 (18.7%) | 1986 (18.9%) | 28 336 (21.8%) | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.08) | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.11) | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.77) |

| Type 1, insulin | 190 (4.8%) | 478 (4.6%) | 18 847 (14.5%) | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.34) | 1.50 (1.19 to 1.90) | 0.28 (0.24 to 0.32) |

| Registration year | ||||||

| 2001–2003 | 1303 (38.0%) | 3422 (37.0%) | 28 741 (38.8%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2004–2005 | 805 (23.4%) | 2239 (24.2%) | 20 024 (27.0%) | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.07) | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.09) | 0.89 (0.81 to 0.97) |

| 2006–2008 | 1325 (38.6%) | 3580 (38.8%) | 25 389 (34.2%) | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.12) | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.19) | 1.15 (1.06 to 1.24) |

| SEIFA | ||||||

| Low | 830 (21.0%) | 2491 (23.8%) | 27 049 (21.1%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Middle | 1543 (39.1%) | 3883 (37.1%) | 51 932 (40.5%) | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.27) | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.25) | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.05) |

| High | 1572 (39.9%) | 4100 (39.1%) | 49 214 (38.4%) | 1.11 (0.99 to 1.24) | 1.07 (0.95 to 1.21) | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.13) |

| Indigenous | ||||||

| No | 3838 (97.2%) | 9969 (95.1%) | 124 033 (95.5%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 113 (2.8%) | 519 (4.9%) | 5867 (4.5%) | 0.57 (0.45 to 0.71) | 0.61 (0.48 to 0.77) | 0.62 (0.52 to 0.75) |

Adjusted for: sex, age category, diabetes status, registration year, SEIFA status and indigenous status.

SEIFA, Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (the Australian Bureau of Statistics' index of relative socio-economic disadvantage).

Results

On 30 June 2008 there were 133 851 registrants in the NDSS who satisfied the LWDS entry criteria, of whom 75 347 (56.3%) did not consent to participate in any research and were excluded (figure 2). Of the remaining 58 504 registrants, 14 439 were invited to participate in the LWDS, 3951 of whom agreed. Complete aggregate information was available for all variables except for registration year and SEIFA. Due to NDSS procedural changes and invalid postcodes, data for 56 264 registration years and 1711 postcodes were not available for the analyses.

Figure 2.

Participation flowchart for the Living with Diabetes Study.

Table 1 shows the results of comparisons of 3951 participants with 10 488 non-participants, and of participants with 129 900 non-study registrants. After adjusting for all covariates, individuals were less likely to participate in the LWDS if they were younger (OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.71) or older (0.89; 0.81 to 0.99) than those aged 50–69 years and had identified themselves as being indigenous Australians (0.61; 0.48 to 0.77). Those who had type 1 diabetes (1.50; 1.19 to 1.90) were more likely to participate in the study. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to specifically investigate the effect of potential confounders. The analyses were re-run six times with one covariate excluded on each occasion. The only effect estimate seen to vary substantially was diabetes status. In the model adjusted across all covariates except age (not shown in table 1), the odds of being a participant if an individual had type 1 diabetes was 1.13 (0.91 to 1.42) greater than if an individual had type 2 diabetes and did not require insulin, while for the fully adjusted model it was 1.50 (1.19 to 1.90).

The comparative analysis between participants and non-study registrants (table 1) shows a number of associational differences when compared to the previous multivariate analysis. The most noticeable is the relationship between participation and diabetes status, as it varies in both strength and direction. These analyses show that compared to those with type 2 diabetes who were not insulin reliant, individuals with type 2 diabetes and insulin reliant (0.71; 0.66 to 0.77) and type 1 diabetes (0.28; 0.24 to 0.32) were less likely to participate. In addition, the association between participation status and sex was also strengthened, with females less likely than males to be participants (0.91; 0.86 to 0.97). There was no evidence of an association between participation and SEIFA, but this was not the case with year of NDSS registration, as registration between 2006 and 2008 was positively associated with participation (1.15; 1.06 to 1.24), while registration between 2004 and 2005 was inversely associated (0.89; 0.81 to 0.97). Associations between participation and the covariates of age and indigenous status were similar in direction and magnitude to those found by the multivariate analysis, except for those aged at least 70 years, which strengthened inversely (0.48; 0.45 to 0.52).

Discussion

The differences observed on the comparisons between participants and non-participants, and between participants and non-study registrants, confirm that the extent of a study's generalisability should be established by comparing study participants to a group of individuals which best represents the target population. In this study, those who agreed to participate in the LWDS were significantly different from the non-study registrants over a number of characteristics, with the most notable being diabetes status. Those with type 2 diabetes who were insulin requiring, were less likely to participate in the LWDS. Individuals were less likely to be participants if they were insulin requiring, with the odds of participation being 29% less likely for those with type 2 diabetes who were insulin requiring, and 72% less likely for those with type 1 diabetes. This parallels the research literature, which suggests that those less healthy are more likely to be non-responders than those in better health.22–24 However, this was not the case when participants were compared to non-participants, which showed a strong association also, but was directionally opposite to the previous result; the adjusted odds of those with type 1 diabetes participating were 50% greater than those who had type 2 diabetes but were not insulin requiring. Such a result indicates that those with type 1 diabetes, although less likely to be invited due to consent issues relating to age at diagnosis,25 were more likely to participate once invited.

Age and Australian indigenous status were also significantly associated with study participation, with age also having a negative confounding effect on the LWDS participation–diabetes status relationship. Unlike the influence of diabetes status, these associations were similar in direction and strength for both comparative analyses.

Although these results are consistent with the literature,5 26 27 they raise the issue of representativeness. Disparities in sample balance have the potential to impact adversely on the estimation of population parameters such as prevalence and incidence metrics.9 28–30

Our initial comparative analysis was between participants and non-participants, and relied solely on information from those invited to participate in the study. This analysis failed to identify an important association between diabetes status and participation.

This was due to the underrepresentation of individuals with type 1 diabetes by a factor of more than 3 in the group of non-participants (4.6%) when compared to registrants not invited to participate in the study (15.4%). Such underrepresentation is the consequence of type 1 diabetes being predominately diagnosed during childhood and the NDSS consent protocol,20 which does not include a systematic updating of consent status at the age of 18 among those registered as a child. Mandatory informed consent, including parental, not only has a negative effect on participation rates overall, but also weakens the representativeness of the study sample by producing unbalanced subgroups among the study participants.25 31 32 This was the case because research consent was not a necessary criterion for an individual to be considered a registrant.

The results of our study should be interpreted within the context of some limitations. First, the generalisability of any study's findings to the target population is very much dependent on register coverage and the quality of its database.16 33 34 Increased levels of coverage and data quality lessen the likelihood of biased sample estimates.35–37 The coverage of the NDSS is estimated to be between 80% and 90%, which is higher than most diabetes registers,20 33 thus giving it the potential to produce sampling frames of a higher data quality than most. Second, in analyses such as these which only utilise one time-point, there is an inability to maximise the information provided by time varying determinants of non-response such as age.23 38 39 Third, due to unavailability of individual-level data for registrants not invited to participate in the study, it was not possible to complete a comparative analysis between participants and non-study registrants that isolated the independent covariate effects after adjustment. It is possible that individual data would have resulted in the associations between participation and a number of covariates being more similar to those found when non-participants were used as the reference group.

Our findings illustrate that the standard procedure of comparing study participants and non-participants in assessing a study's generalisability can be compromised by the issue of research consent when disease registers are used as a source of recruitment. Whenever possible, a clearer assessment should be sought by extending this standard practice to a secondary analysis by sourcing the largest possible reference group that is inclusive of non-participants. For prospective population-based cohort studies, researchers should endeavour to source a group that contains all potential participants who satisfied inclusion criteria but have not been able to participate. As findings can be influenced by the issue of research consent, where available, chronic disease registers should be utilised fully in any assessment of generalisability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to especially thank the participants of the Living with Diabetes Study; without their participation this research would not be possible. Also, our sincere thanks go to Diabetes Australia and the National Diabetes Services Scheme for working with us to make it possible to recruit participants to the Living with Diabetes Study. In addition, we would also like to thank all members of the Living with Diabetes Study team for their ongoing support and input.

Footnotes

To cite: David M, Ware R, Donald M, et al. Assessing generalisability through the use of disease registers: findings from a diabetes cohort study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000078. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000078

Funding: This research was funded by the Australian Research Council (DP0988805) and Queensland Health through the Queensland Strategy for Chronic Disease 2005–2015.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by The University of Queensland's Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee (BSSERC).

Contributors: All authors designed the study. M Donald was responsible for data acquisition. M David and R Ware analysed the data. M David drafted the initial manuscript. R Ware, M Donald and R Alati critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data used in this study were de-identified (personal identifiers were removed or disguised) before usage. These data are organised and held at the School of Population Health at The University of Queensland. The Living with Diabetes Study's homepage includes information on methodology and study updates including preliminary descriptive findings (www.lwds.org.au). Researchers are invited to contact the research team to explore options for collaborative work.

References

- 1.Tabák AG, Jokela M, Akbaraly TN, et al. Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the Whitehall II study. Lancet 2009;373:2215–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mrena S, Virtanen SM, Laippala P, et al. Models for predicting type 1 diabetes in siblings of affected children. Diabetes Care 2006;29:662–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szklo M. Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiol Rev 1998;20:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deeg DJH. Attrition in longitudinal population studies: Does it affect the generalizability of the findings? An introduction to the series. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:213–15 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drivsholm T, Eplov LF, Davidsen M, et al. Representativeness in population-based studies: a detailed description of non-response in a Danish cohort study. Scand J Public Health 2006;34:623–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sim J. The external validity of group comparative and single system studies. Physiotherapy 1995;81:263–70 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerrish K, Lacey A, eds. The Research Process in Nursing. 6th edn Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry AE. How attrition impacts the internal and external validity of longitudinal research. J Sch Health 2005;75:267–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livingston PM, Lee SE, McCarty CA, et al. A comparison of participants with non-participants in a population-based epidemiologic study: The Melbourne Visual Impairment Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1997;42:73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groves RM, Floyd J, Fowler JR, et al. Survey Methodology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalsbeek W, Heiss G. Building bridges between populations and samples in epidemiological studies. Annu Rev Public Health 2000;21:147–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boardman HF, Thomas E, Ogden H, et al. A method to determine if consenters to population surveys are representative of the target study population. J Public Health 2005;27:212–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekkers OM, von Elm E, Algra A, et al. How to assess the external validity of therapeutic trials: a conceptual approach. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torner A, Duberg AS, Dickman P, et al. A proposed method to adjust for selection bias in cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:602–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonsson S, Hedblad B, Engstrom G, et al. Influence of obesity on cardiovascular risk. Twenty-three-year follow-up of 22 025 men from an urban Swedish population. Int J Obes 2002;26:1046–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brewster DH, Stockton D, Harvey J, et al. Reliability of cancer registration data in Scotland, 1997. Eur J Cancer 2002;38:414–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molster C, Bower C, O'Leary P. Community attitudes to the collection and use of identifiable data for health research–is it an invasion of privacy? Aust N Z J Public Health 2007;31:313–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gershon AS, Tu JV. Data validity and coverage in the Danish National Health Registry. A literature review. Can Med Assoc J 2008;178:871–318362384 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman KJ. The rise and fall of epidemiology, 1950–2000 AD. N Engl J Med 1981;304:600–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Diabetes Prevalence in Australia: An Assessment of National Data Coverage. Diabetes series no14. Canberra: AIHW, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Australian Bureau of Statistics Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Area's (SEIFA). Canberra: ABS, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso A, Seguí-Gómez M, de Irala J, et al. Predictors of follow-up and assessment of selection bias from dropouts using inverse probability weighting in a cohort of university graduates. Eur J Epidemiol 2006;21:351–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coley N, Gardette V, Toulza O, et al. Predictive factors of attrition in a cohort of Alzheimer disease patients. Neuroepidemiology 2008;31:69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holden L, Ware RS, Passey M. Characteristics of nonparticipants differed based on reason for nonparticipation: a study involving the chronically ill. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:728–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:643–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odierna DH, Schmidt LA. The effects of failing to include hard-to-reach respondents in longitudinal surveys. Am J Public Health 2009;99:1515–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hazell ML, Morris JA, Linehan MF, et al. Factors influencing the response to postal questionnaire surveys about respiratory symptoms. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:165–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware RS, Williams GM, Aird RL. Participants who left a multiple-wave cohort study had similar baseline characteristics to participants who returned. Ann Epidemiol 2006;16:820–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brilleman SL, Pachana NA, Dobson AJ. The impact of attrition on the representativeness of cohort studies of older people. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:71–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson N, Wooden M. Identifying factors affecting longitudinal survey response. In: Lynn P, ed Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys. New York: Wiley, 2009:157–81 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rojas NL, Sherrit L, Harris S, et al. The role of parental consent in adolescent substance use research. J Adolesc Health 2008;42:192–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kho ME, Duffett M, Willison DJ, et al. Written informed consent and selection bias in observational studies using medical records: systematic review. Br Med J 2009;338:b866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joshy G, Simmons D. Diabetes information systems: a rapidly emerging support for diabetes surveillance and care. Diabetes Technol Ther 2006;8:587–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nickelsen TN. Data validity and coverage in the Danish National Health Registry. A literature review. Ugeskr Laeger 2001;164:33–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi BC, Pak AW. Understanding and minimizing epidemiologic bias in public health research. Can J Public Health 2005;96:284–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biemer PP, Lyberg L, Wiley J. Introduction to Survey Quality. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Online Library, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Coverage bias in traditional telephone surveys of low-income and young adults. Public Opin Q 2007;71:734–49 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siddiqui O, Flay BR, Hu FB. Factors affecting attrition in a longitudinal smoking prevention study. Prev Med 1996;25:554–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Che YH, Assanangkornchai S, McNeil E, et al. Predictors of early dropout in methadone maintenance treatment program in Yunnan province, China. Drug Alcohol Rev 2010;29:263–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.