Abstract

Objectives

Since ageing is associated with a decline in pulmonary function, heart rate variability and spontaneous baroreflex, and recent studies suggest that yoga respiratory exercises may improve respiratory and cardiovascular function, we hypothesised that yoga respiratory training may improve respiratory function and cardiac autonomic modulation in healthy elderly subjects.

Design

76 healthy elderly subjects were enrolled in a randomised control trial in Brazil and 29 completed the study (age 68±6 years, 34% males, body mass index 25±3 kg/m2). Subjects were randomised into a 4-month training program (2 classes/week plus home exercises) of either stretching (control, n=14) or respiratory exercises (yoga, n=15). Yoga respiratory exercises (Bhastrika) consisted of rapid forced expirations followed by inspiration through the right nostril, inspiratory apnoea with generation of intrathoracic negative pressure, and expiration through the left nostril. Pulmonary function, maximum expiratory and inspiratory pressures (PEmax and PImax, respectively), heart rate variability and blood pressure variability for spontaneous baroreflex determination were determined at baseline and after 4 months.

Results

Subjects in both groups had similar demographic parameters. Physiological variables did not change after 4 months in the control group. However, in the yoga group, there were significant increases in PEmax (34%, p<0.0001) and PImax (26%, p<0.0001) and a significant decrease in the low frequency component (a marker of cardiac sympathetic modulation) and low frequency/high frequency ratio (marker of sympathovagal balance) of heart rate variability (40%, p<0.001). Spontaneous baroreflex did not change, and quality of life only marginally increased in the yoga group.

Conclusion

Respiratory yoga training may be beneficial for the elderly healthy population by improving respiratory function and sympathovagal balance.

Trial Registration

CinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00969345; trial registry name: Effects of respiratory yoga training (Bhastrika) on heart rate variability and baroreflex, and quality of life of healthy elderly subjects.

Article summary

Article focus

Yoga respiratory training may improve respiratory function and cardiac autonomic modulation in healthy elderly subjects.

Key messages

Yoga respiratory training improves respiratory function by increasing PEmax and PImax.

Yoga respiratory training improves both cardiac autonomic modulation by lowering the low frequency component, and the sympathovagal balance evaluated by heart rate variability.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study design allowed evaluation of heart rate variability without confounding by the effects of drugs, including β-blockers, that can interfere with autonomic modulation.

As the sample size was small and only included healthy elderly subjects, the results should be extrapolated with caution to elderly subjects with significant comorbidities.

The respiratory exercises were taught to highly motivated yoga practitioners, and so the general elderly population may find it difficult to learn them.

Paced breathing during the collection of heart rate variability measurements may influence autonomic variables but allowed the confounding effects of respiratory training on the pattern of breathing to be avoided.

Introduction

Life expectancy is steadily increasing across the world. In Western Europe, for example, life expectancy rose by about 30 years during the 20th century.1 Ageing is associated with progressive worsening of lung function,2 which is related to loss of respiratory muscle mass, along with diminished thoracic mobility and compliance, with reduced pulmonary function and efficiency.3 Ageing is also associated with profound changes in cardiovascular neural control, as witnessed by decreased heart rate variability,4 increased sympathetic drive and reduced spontaneous baroreflex gain.5 6 All these changes may contribute to poor adaptive control of the cardiorespiratory system, and a greater incidence of cardiovascular diseases, characteristic of the natural ageing process,1 and reduced quality of life.7

There is increasing evidence that breathing exercises have beneficial effects on the respiratory system,8 blunt sympathetic excitatory pathways9 10 and enhance cardiorespiratory adaptation to hypoxia.11 12 Respiratory exercises are a relatively simple, low-cost intervention that can be incorporated into people's daily routine and may have a positive impact on respiratory and cardiovascular systems in the elderly. Bhastrika pranayama is a comprehensive yoga respiratory exercise that combines rapid shallow breathing using expiratory muscles with periods of slow inspiration and expiration through one nostril that are interspersed with inspiratory apnoeas associated with further activation of chest inspiratory muscles. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that a 4-month respiratory yoga training program (Bhastrika pranayama) improves respiratory function, cardiac sympathovagal balance and quality of life in healthy elderly subjects.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We recruited subjects from among the participants of a yoga training course for the elderly offered by the Sports Center of the University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. This yoga course consists of two 1 h classes each week of stretching exercises based on the yoga tradition. These classes are open to elderly members of the local community. Exclusion criteria were: age <60 years, previous knowledge of and training in yoga respiratory exercises, inability to comply with the protocol (not attending >40% of classes), presence of cardiovascular or any other diseases, and use of medication that could affect autonomic modulation of the heart. All subjects who entered the study underwent a standard clinical and biochemical evaluation, which included measurement of total blood cholesterol and its fractions, glucose, creatinine and thyroid stimulating hormone. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. All subjects were informed about the study and signed a consent form.

Study protocol

After being enrolled, patients were randomised to either a yoga respiratory training group or a control group. Fifteen papers with the word ‘yoga’ and 15 with the word ‘control’ were put in an envelope and the paper each subject drew out determined their group. Evaluations, described below, were conducted in the morning at study entry (baseline) and at the end of the study (4 months).

Evaluations

Pulmonary function test

Pulmonary spirometry was measured with a dry bellows Koko Spirometer (Pulmonary Data System Instrumentation, Louisville, Colorado, USA) according to the ATS/ERS Task Force statement on the standardisation of lung function testing.13 Measurements included forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory flow from 25% to 75% of FVC (FEF25–75) and peak expiratory flow rate. Predicted normal values were determined using the equations reported by Duarte et al.14

Maximal expiratory (PEmax) and inspiratory (PImax) pressures were measured at the mouth using a portable pressure gauge (Indumed, São Paulo, Brazil) applied under static conditions following the method proposed by Black and Hyatt.15 PEmax was measured at total lung capacity and PImax at functional residual capacity. The highest of three valid consecutive efforts after a minimum of three practice attempts, was recorded as PEmax and PImax. The results are expressed as absolute and relative values (percentage of the predicted for the same age group).15

Heart rate variability

Heart rate variability was measured in a quiet room. First, heart rate and auscultatory blood pressure were measured after the subject had been sitting quietly for 5 min. The mean of three consecutive measurements with a maximum variation of 4 mm Hg for both systolic and diastolic blood pressures was accepted.16 The subjects were monitored by ECG from a precordial lead (DX2020; Dixtal, São Paulo, Brazil) and beat-to-beat blood pressure (Portapres; TNO Biomedical Instrumentation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and respiration (Respitrace; Ambulatory Monitoring, White Plains, New York, USA) were measured. The Respitrace instrument was calibrated against a pneumotachograph, as previously described.17 The subjects were monitored for 20 min while sitting at rest for 5 min. The sample frequency was 1000 Hz per channel. During the acquisitions, subjects were instructed to breathe following a recorded pacing instruction at 12 cycles/min, to maintain a respiratory frequency at 0.2 Hz. The signals were acquired and analysed by a customised computer program (LabView; National Instruments, Austin, Texas, USA). Autoregressive spectral analysis was applied to the data; the theoretical and analytical procedures have been described previously.18 In brief, a derived-threshold algorithm provided the series of R–R intervals from the ECG, and the respiratory activity signal was sampled once every cardiac cycle. The calculation was performed on stationary segments of the time series, with at least 120 points. Autoregressive parameters were estimated by the Levinson–Durbin recursion, and the order of the model was chosen according to Akaike's criterion. Autoregressive spectral decomposition allows automatic quantification of the centre frequency and power of each relevant oscillatory component present in the time series. Based on the central frequencies, components were assigned as low (LF; 0.04—0.15 Hz) or high (HF; 0.15—0.5 Hz) frequency. HF power was determined according to the significance of coherence with the respiratory spectrum. HF and LF components were reported also in normalised units (ν), which are obtained by calculating the percentage of the LF and HF variability with respect to the total power (all components from 0 to 0.5 Hz) after subtracting the power of the very low frequency component (frequencies <0.04 Hz). The normalisation procedure tends to minimise the effect of the changes in total power on the absolute values of LF and HF components of heart rate variability.18 19 Normalised LF and HF components of R–R variability were considered, respectively, as markers of cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation, and the ratio between them (LF/HF) was considered as an index of the autonomic modulation of the heart.20

Spontaneous baroreflex

Spontaneous baroreflex was assessed using the sequence method described by Bertinieri et al,21 22 which is based on the identification of three or more consecutive beats in which progressive increases/decreases in systolic blood pressure are followed by progressive lengthening/shortening of the R–R interval. The threshold values for including beat-to-beat systolic blood pressure and R–R interval changes in a sequence were set at 1 mm Hg and 6 ms, respectively. Similar to the procedure followed for the bolus injection of vasoactive drugs or for the Valsalva manoeuvre, the sensitivity of the reflex is obtained by computing the slope of the regression line relating changes in systolic pressure to changes in R–R interval. All computed slopes are finally averaged to obtain the spontaneous baroreflex.

Quality of life

Quality of life is defined by the World Health Association23 as a multifactorial variable consisting of many components. In order to evaluate these variables, we administered the WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire for Elderly People (WHOQOL-OLD). This questionnaire has been translated and validated for use in Portuguese.24 The WHOQOL-OLD questionnaire is divided into six subsets (sensory abilities; autonomy; past, present and future activities; social participation; death and dying; and intimacy). Subjects were instructed to answer a set of 24 questions which were further divided into the six categories mentioned above (four questions each). They were asked to score answers from 1 to 5 (1: nothing; 5: extremely); the sum of all scores gave overall quality of life, and the sum of the four questions in each subset showed specific components to be more positive as the result increased. In order to allow comparisons with other questionnaires, the total score and the scores of each subset were transformed into a 0–100 scale. Cronbach's α coefficient (0.815) indicated results between baseline and 4 months were consistent.

Training program

The training program consisted of 30 min of supervised training classes immediately after the twice weekly routine yoga class. In addition, the subjects were instructed to perform the specific exercises twice a day for 10 min (in the morning and afternoon). All subjects were instructed to keep a diary that was returned to the yoga instructor once a month.

The intervention in the control group consisted of stretching and yoga posture exercises that were similar to the exercises carried out in the previous yoga classes. Respiratory training was based on traditional Bhastrika pranayama exercises. This is a comprehensive respiratory exercise and, briefly, is composed of kapalabhati interspersed with surya bedhana.25 Kapalabhati consisted of 45 rapid active expirations generated by contractions of the rectus abdominalis. During kapalabhati, expiration is active and inspiration is passive. Surya bedhana is slow inspiration through the right nostril, followed by a comfortable apnoea and a much slower, yet comfortable, expiration. During this voluntary inspiratory apnoea, one must perform three manoeuvres (or bandhas): jalandhara (strongly press the chin on the jugular notch, with the nostrils pressed with the fingers), uddyiana (chest expansion after jalandhara bandha, taking the chest to its maximal inspiratory position) and mula (perineum contraction). The sequence of respiratory exercises comprising Bhastrika pranayama is shown in the online supplemental video.

Statistical analysis

Based on the assumption of a 20% or greater decrease in sympathovagal balance in 5% of controls and at least 50% of the intervention group (yoga), to obtain a power of 80% the required sample size was calculated as 15 subjects in each group. Once normality was ensured, a two-way analysis of variance was used to evaluate the effects of intervention on all physiological variables. Significance was accepted as p<0.05. When significance was found, the Holm–Sidak post hoc test was applied. Results were analysed with SPSS software v 16.0.

Results

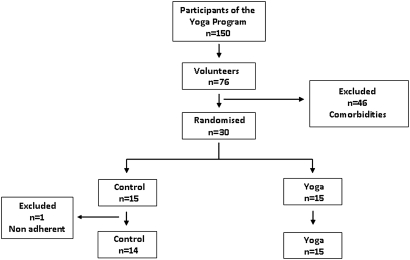

Of 150 elderly yoga program participants, 76 volunteered to participate in the study. Forty-six subjects were excluded, mainly due to atrial fibrillation, other diseases and the use of medication including antihypertensive and thyroid hormone replacement drugs. Thirty subjects entered the study; however, one patient assigned to the control group was excluded because he failed to attend the scheduled classes (figure 1). The demographic and biochemical characteristics of the subjects assigned to the control and yoga groups were similar (table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study recruitment.

Table 1.

Demographic and biochemical characteristics of the population according to the assigned intervention

| Control (n=14) | Yoga (n=15) | p Value | |

| Anthropometric data | |||

| Female, n | 10 | 09 | |

| Age, years | 69±7 | 68±4 | 0.631 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25±3 | 24±3 | 0.336 |

| Cardiovascular data | |||

| Heart rate, bpm | 65±7 | 64±10 | 0.265 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130±11 | 131±12 | 0.974 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 78±7 | 85±12 | 0.103 |

| Biochemical analysis | |||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 197±41 | 202±27 | 0.887 |

| Low density lipoprotein, mg/dl | 108±38 | 115±25 | 0.636 |

| High density lipoprotein, mg/dl | 57±8 | 55±9 | 0.619 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 119±47 | 119±39 | 0.411 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dl | 99±18 | 90±10 | 0.149 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.0±0.2 | 0.9±0.3 | 0.531 |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone, mU/ml | 3.2±2.3 | 3.7±6.8 | 0.881 |

Data are means±SD.

Pulmonary function test

Spirometric parameters between groups were similar at study entry. The relative values (% predicted) in the control and yoga groups were: FVC: 111±18 and 103±12; FEV1: 111±14 and 97±12; FEF25–75: 103±26 and 82±28; peak expiratory flow rate: 92±4 and 81±4; PEmax: 80±20 and 78±21; and PImax: 53±16 and 55±15, respectively.

After the 4 months of training, there were no significant changes in any parameters in the control group. Improvements in FVC and FEV1 in the yoga group did not reach statistical significance compared with the control group (table 2). In contrast, PEmax and PImax increased significantly in the yoga compared with the control group (figure 2).

Table 2.

Spirometric variables at baseline and after 4 months for the control and yoga groups

| Variables | Control (n=14) |

Yoga (n=15) |

||||

| Baseline | 4 Months | p Value | Baseline | 4 Months | p Value | |

| FVC, litres | 3.2±0.6 | 3.1±0.6 | 0.2 | 3.2±0.8 | 3.3±0.8 | 0.005 |

| FEV1, litres | 2.4±0.4 | 2.4±0.4 | 0.6 | 2.3±0.6 | 2.4±0.6 | 0.005 |

| FEF25–75, l/s | 2.1±0.6 | 2.2±0.7 | 0.8 | 1.8±0.7 | 1.9±0.5 | 0.7 |

| PEFR, l/s | 6.5±1.9 | 5.8±2.0 | 0.09 | 6.0±2.2 | 6.3±2.0 | 0.3 |

Data are expressed as means±SD.

FEF25–75, forced expiratory flow from 25% to 75% of FVC; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; PEFR, peak expiratory flow rate.

Figure 2.

Individual values for maximum expiratory power (PEmax) and maximum inspiratory power (PImax). There were no significant differences at baseline between groups for both variables. The yoga group showed significant increases in PEmax and PImax at 4 months. The difference between groups became significant for PEmax at 4 months. Data are expressed as means±SD.

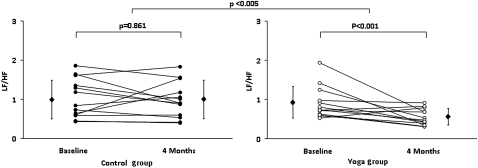

Heart rate variability

All frequency domain heart rate variability parameters, both in absolute and normalised units, were similar at study entry between the two groups. After 4 months of training, there were no significant changes in the parameters analysed in the control group. In contrast, the yoga group showed a significant decrease in the LF component of heart rate variability and in the LF/HF ratio (figure 3). Results are summarised in table 3.

Figure 3.

Individual values for sympathovagal balance (LF/HF). There was no significant difference at baseline between groups. There was a decrease in LF/HF from baseline to 4 months due to a significant decrease in the yoga group (p<0.001, intra-group paired t test for repeated measures). HF, high frequency component of heart rate variability; LF, low frequency component of heart rate variability. Data are expressed as means±SD.

Table 3.

Heart rate variability at baseline and after 4 months for the control and yoga groups

| Variables | Control (n=13) |

Yoga (n=13) |

||||

| Baseline | 4 Months | pValue | Baseline | 4 Months | pValue | |

| Variance | 1458±1399 | 1385±1343 | 0.70 | 978±797 | 910±465 | 0.57 |

| LF, ms2/Hz | 514±405 | 334±280 | 0.95 | 383±297 | 123±87 | 0.04* |

| HF, ms2/Hz | 642±676 | 496±482 | 0.88 | 431±389 | 262±206 | 0.46 |

| LF, ν | 40±13 | 41±13 | 0.81 | 40±11 | 27±8 | 0.001* |

| HF, ν | 45±14 | 45±9 | 0.53 | 47±9 | 54±15 | 0.40 |

Data are expressed as means±SD.

p<0.05 for comparisons between groups.

HF, high frequency component of heart rate variability; LF, low frequency component of heart rate variability; ν, normalised units, excluding the very low frequency component of heart rate variability.

Spontaneous baroreflex

Spontaneous baroreflex gain was similar between groups at study entry. There were no significant changes in either group at the end of the study: spontaneous baroreflex gain in the control group at baseline and at 4 months was 9.2±6.9 and 8.0±5.7 ms/mm Hg and in the yoga group 10.0±9.3 and 6.8±4.0 ms/mm Hg (p=0.462).

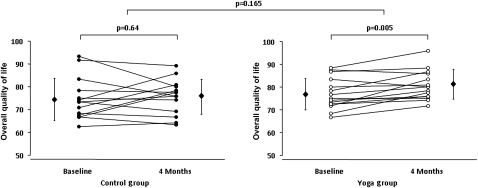

Quality of life

Overall quality of life and all its subsets were similar between groups at study entry. Although overall quality of life did not significantly increase with time (0.052), it did show a strong trend (figure 4). Among the subsets, autonomy and sense of interaction between the present, past and future showed significant increases independent of group from baseline to 4 months. The yoga group had marginal changes in overall quality of life, autonomy and interaction between the present, past and future. Results are summarised in table 4.

Figure 4.

Individual values for overall quality of life. There was no significant difference at baseline between groups. There was a strong tendency (0.052) towards increased quality of life from baseline to 4 months, apparently due to a significant increase in the yoga group (p<0.005, intra-group paired t test for repeated measures). Bars represent means±SD.

Table 4.

Scores of quality of life obtained from the World Health Organization Questionnaire for Quality of Life of Elderly People (WHOQOL-OLD) at baseline and after 4 months for the control and yoga groups

| Variables | Control (n=14) |

Yoga (n=15) |

||||

| Baseline | 4 Months | p Value | Baseline | 4 Months | p Value | |

| QOL | 75±9 | 76±8 | 0.6 | 77±7 | 81±6 | 0.005 |

| Autonomy | 68±15 | 71±20 | 0.3 | 69±19 | 78±10 | 0.04* |

| PPF | 73±12 | 76±15 | 0.4 | 74±7 | 79±8 | 0.01* |

| Social participation | 79±13 | 81±10 | 0.6 | 80±9 | 83±9 | 0.2 |

| DD | 76±18 | 71±18 | 0.3 | 78±17 | 81±13 | 0.2 |

| Sensorial functioning | 76±17 | 78±14 | 0.7 | 81±14 | 83±11 | 0.3 |

| Intimacy | 76±18 | 76±13 | 0.9 | 81±8 | 79±8 | 0.3 |

Data are expressed as means±SD.

p<0.05 for the comparisons between baseline and 4 months, independent of group.

DD, fear of death and dying; PPF, sense of interaction between present past and future; QOL, overall quality of life.

Discussion

In the present randomised study, we found that a breathing exercise program derived from yoga is beneficial for the cardiorespiratory system in healthy elderly subjects. Yoga respiratory training resulted in significant improvements in PEmax and PImax. In addition, yoga respiratory training produced a significant decrease in the LF component of heart rate variability and thus a shift in the sympathovagal balance towards a reduction in sympathetic predominance.

This study has some limitations. The sample was composed of highly motivated healthy volunteers who were used to yoga practice; the general elderly population may find it difficult to learn the respiratory exercises. In addition, the results should be extrapolated with caution to elderly subjects with significant comorbidities, which are extremely common in this age group. On the other hand, the study design allowed us to evaluate heart rate variability without the confounding effects of drugs, including β-blockers, that may interfere with autonomic modulation. The paced breathing during the measurement of heart rate variability may have influenced autonomic variables. On the other hand, yoga practitioners tend to breathe more slowly than non-practitioners, and this would have the effect of shifting the respiratory sinus arrhythmia into the LF band, thus giving the false impression of increased sympathetic activity despite increased parasympathetic predominance. Therefore, paced breathing allowed us to avoid the confounding effects of respiratory training on the respiratory pattern of breathing that would in turn directly affect heart rate variability. Our study showed no effects of yoga respiratory training on spontaneous baroreflex measured by linear analysis. Spontaneous baroreflex may show different results depending on the method of analysis. However, we have found no differences between groups when spontaneous baroreflex was analysed by the squared root of the ratio of the autoregressive powers of R–R interval and systolic blood pressure series in the LF and HF ranges (data not shown).26 Finally, the observation of non-significant effects of yoga training on spontaneous baroreflex and quality of life may be at least in part due to the small sample size.

The progressive loss of muscle mass seen in ageing may be partly responsible for the reduced respiratory capacity in the elderly.27 Physical exercise training has been shown to be beneficial for the elderly and to increase fitness and aerobic capacity.28 The effects of respiratory exercises may vary according to the time of intervention, exercise protocol and population studied. While several previous studies investigated the acute effects of respiratory exercises on both the respiratory9 and cardiovascular9 10 systems, one of the strengths of our study is that we set up a long-term training program. The results may also be dependent on the population studied. Vempati et al29 found an increase in FEV1 after 8 weeks of yoga training in a group of patients with asthma. Our subjects did not have pulmonary disease, and the increases in FVC and FEV1 after yoga training were marginal and did not reach statistical significance compared with the control group. Previous studies reporting negative results of yoga training on FVC and FEV130 31 only investigated the effects of slow breathing. The respiratory exercises used in this protocol (Bhastrika pranayama) are specifically suited to the respiratory system, and exercise both inspiratory and expiratory muscles. Kapalabhati (fast expirations) involve abdominal wall muscles used for expiration, while surya bedhana (slow breath with retention) affects inspiratory muscles in either the inspiratory (concentric isokinetic contraction), retentive (isometric contraction) or expiratory (eccentric isokinetic contraction) phases. Thus, Bhastrika pranayama may increase expiratory as well as inspiratory muscle performance, improving the capacity of the thoracic compartment to create negative and positive pressures in the respiration process. Although the elderly subjects in the present study had PEmax and PImax values in the normal range at study entry, both parameters improved significantly after the yoga program.

The respiratory and cardiovascular systems are tightly linked. In addition to the beneficial effects on the respiratory system, yoga respiratory training resulted in a significant decrease in sympathovagal balance and a marked and significant decrease in the LF component of heart rate variability. These parameters indicate a positive shift in cardiac autonomic modulation towards parasympathetic predominance. It has been previously shown that slow comfortable breaths lead to an increase in parasympathetic modulation.9 Bernardi et al11 found preserved oxygenation without increased minute ventilation in response to hypoxic exposure in yoga trainees compared with a non-trained control group. The authors suggest that yoga respiratory training produced a different adaptive cardiorespiratory strategy. Consistent with this hypothesis, Pomidori et al8 showed that yoga breathing exercises induced greater resting oxygen saturation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. We speculate that the effects of yoga respiratory training on sympathovagal balance may be due to a central modulator regulatory effect. Since frailty increases with ageing8 and is characterised as a decrease in many cardiovascular4–7 and respiratory4–8 parameters, it may be that the improvements in respiratory function and cardiovascular autonomic modulation may slow down the frailty process and increase quality of life in elderly subjects. In fact, at least two studies32 33 have investigated the effects of a yoga-based lifestyle modification on subjective well-being, and verified its effectiveness.

In conclusion, 4 months of respiratory training in Bhastrika pranayama increased respiratory function and improved cardiac parasympathetic modulation in a group of healthy elderly subjects. Yoga respiratory training is easy to perform at low cost and may positively influence the cardiorespiratory system. Since frailty develops with ageing with decreases in many cardiovascular4–6 and respiratory4–6 parameters, further studies will be necessary to test the hypothesis that improvements in both respiratory function and cardiovascular autonomic modulation may counteract the development of frailty. The effects of yoga may be broader than observed in this study. At least two studies32 33 have shown that yoga-based lifestyle modification is beneficial for subjective well-being. These effects together may slow down the natural progression of frailty with ageing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Amato for providing equipment without which this research would not have been possible, as well as for statistical support.

Footnotes

To cite: Santaella DF, Devesa CRS, Rojo MR, et al. Yoga respiratory training improves respiratory function and cardiac sympathovagal balance in elderly subjects: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000085. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000085

Funding: Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the University of São Paulo Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil.

Contributors: DFS, ACRDS and MRR designed the protocol. DFS conducted the yoga and control classes, and collected and analysed the clinical data. DFS, GLF, KRC and NM drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content. MBPA and LFD contributed substantially to the conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. All authors interpreted the data, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We agree to share the published data as open access.

References

- 1.Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, et al. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 2009;374:1196–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan ED, Welch CH. Geriatric respiratory medicine. Chest 1998;114:1704–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein PK, Barzilay JI, Chaves PH, et al. Heart rate variability and its changes over 5 years in older adults. Age Ageing 2009;38:212–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauvel JP, Cerutti C, Mpio I, et al. Aging process on spectrally determined spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity: a 5-year prospective study. Hypertension 2007;50:543–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaye DM, Esler MD. Autonomic control of the aging heart. Neuromolecular Med 2008;10:179–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drewnowsky A, Evans WJ. Nutrition, physical activity, and quality of life in older adults: summary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;V56A:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomidori L, Campigotto F, Amatya TM, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of Yoga breathing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2009;29:133–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raupach T, Bahr F, Herrmann P, et al. Slow breathing reduces sympathoexcitation in COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;32:387–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal GK, Velkumary S, Madanmohan Effects of short-term practice of breathing exercises on autonomic functions in normal human volunteers. Indian J Med Res 2004;120:115–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardi L, Porta A, Gabutti A, et al. Modulatory effects of respiration. Auton Neurosci 2001;90:47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardi L, Passino C, Spadacini G, et al. Reduced hypoxic ventilatory responde with preserved blood oxygenation in Yoga trainees and himalayan buddhist monks at altitude: evidence of a different adaptative strategy? Eur J Appl Physiol 2007;99:511–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duarte AA, Pereira CA, Barreto SC, et al. Validation of new Brazilian predicted values for forced spirometry in Caucasians and comparison with predicted values obtained using other reference equations (In English, Portuguese). J Bras Pneumol 2007;35:527–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black LF, Hyatt RE. Maximal respiratory pressures: normal values and relationship to age and sex. Am Rev Respir Dis 1969;99:696–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detectioon, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobin MJ, Guenther SM, Perez W, et al. Accuracy of the respiratory inductive plethysmograph during loaded breathing. J Appl Physiol 1987;62:497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anonymous. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J 1996;17:354–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montano N, Ruscone TG, Porta A, et al. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability to assess the changes in sympathovagal balance during orthostatic tilt. Circulation 1994;90:1826–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montano N, Porta A, Cogliati C, et al. Heart rate variability explored in the frequency domain: a tool to investigate the link between heart and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2009;33:71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertinieri G, Di Rienzo M, Cavallazzi A, et al. A new approach to analysis of the arterial baroreflex. J Hypertens Suppl 1985;3:S79–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertinieri G, Di Rienzo M, Cavallazzi A, et al. Evaluation of baroreceptor reflex by blood pressure monitoring in unanesthetized cats. Am J Physiol 1988;254:H377–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chachamovit E, Fleck MP, Trentini C, et al. Brazilian WHOQOL-OLD Module Version: a Rasch analysis of a new instrument. Rev Saude Publica 2008;42:308–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleck MP, Chachamovich E, Trentini C. Development and validation of the Portuguese version of the WHOQOL-OLD module. Rev Saude Publica 2006;40:785–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuvalayananda Swami. Pranayama. Trad. Roldano Giuntoli. São Paulo: Phorte, 2008:312 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernardi L, De Barbieri G, Rosengård-Bärlund M, et al. New method to measure and improve consistency of baroreflex sensitivity values. Clin Auton Res 2010;20:353–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssens JP. Aging of the respiratory system: impact on pulmonary function tests and adaptation to exertion. Clin Chest Med 2005;26:469–84, vi–vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anonymous. American College of Sports Medicine Position Standard. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:992–1008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vempati R, Bijlani RL, Deepak KK. The efficacy of a comprehencive lifestile modification programme based on Yoga in the manegement of bronchial asthma: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm Med 2009;9:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper S, Oborne J, Newton S, et al. Effect of two breathing exercises (Buteyko and pranayama) in Asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Thorax 2003;58:674–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slader CA, Reddel HK, Spencer LM, et al. Double blind randomized controlled trial of two different breathing techniques in the management of asthma. Thorax 2006;61:651–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oken BS, Zajdel D, Kishiyama S, et al. Randomized, controlled, six-month trial of yoga in health seniors: effects on cognition and quality of life. Altern Ther Health Med 2006;12:40–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma R, Gupta N, Bijlani RL. Effect of yoga based lifestile intervention on subjective well-being. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 2008;52:123–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.