Abstract

Background

Patients living with fibromyalgia strongly prefer to access health information on the web. However, the majority of subjects in previous studies strongly expressed their concerns about the quality of online information resources.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to evaluate existing online fibromyalgia information resources for content, quality and readability by using standardised quality and readability tools.

Methods

The first 25 websites were identified using Google and the search keyword ‘fibromyalgia’. Pairs of raters independently evaluated website quality using two structured tools (DISCERN and a quality checklist). Readability was assessed using the Flesch Reading Ease score maps.

Results

Ranking of the websites' quality varied by the tool used, although there was general agreement about the top three websites (Fibromyalgia Information, Fibromyalgia Information Foundation and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases). Content analysis indicated that 72% of websites provided information on treatment options, 68% on symptoms, 60% on diagnosis and 40% on coping and resources. DISCERN ratings classified 32% websites as ‘very good’, 32% as ‘good and 36% as ‘marginal’. The mean overall DISCERN score was 36.88 (good). Only 16% of websites met the recommended literacy level grade of 6–8 (range 7–15).

Conclusion

Higher quality websites tended to be less readable. Online fibromyalgia information resources do not provide comprehensive information about fibromyalgia, and have low quality and poor readability. While information is very important for those living with fibromyalgia, current resources are unlikely to provide necessary or accurate information, and may not be usable for most people.

Article summary

Article focus

The purpose of the study was to gain a better understanding of the online information resources available for people with fibromyalgia and to evaluate those resources for content, quality and readability.

To determine the content, website quality and readability of the most readily retrieved information available on the web when searching for fibromyalgia information.

Key messages

Most existing websites do not provide comprehensive information on fibromyalgia.

Websites are highly variable in terms of quality.

Higher quality websites do not present information in language/reading levels appropriate for the general population.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study examines the quality of online fibromyalgia resources.

Standardised quality and readability tools were used to assess quality and readability.

There is no gold standard for comparison or ways to evaluate the quality of websites.

The quality issue was discussed using critical appraisal tools designed for the lay public.

The readability score may vary for some websites as it may be related to the use of technical terms such as fibromyalgia.

Introduction

More than 70 000 websites offer health information for consumers and the number is increasing daily.1 Many of these websites are accessed by people with fibromyalgia to self-manage their own health. However, it is unknown if these websites are consistent with the literacy and health needs of such users. However, we do know that web-based information has the potential to educate and empower consumers by providing information about their health problems and by helping them make informed decisions about their health.2–5

The extent of the interest in web-based health information is indicated by high and increasing usage.6 7 In Canada about 8.7 million people use the internet to obtain medical and health-related information, with women being more likely to search for health information on specific diseases than men.6 In addition, 54%–79% of those seeking information expressed concerns about the quality of online health information.6 Similarly, in the USA, the number of adults who look for health information online has increased from 46% in 2000 to 61% in 2009.7 Many (66%) of these online health information seekers discuss their concerns about the lack of quality of online health information sources with their healthcare providers.7 Thus, researchers at the Pew Internet and American Life Project anticipate that as more people access the internet for health information, their concern about quality will also continue to grow.7

The internet is now an important resource for people living with fibromyalgia.8–10 Fibromyalgia is described as an invisible chronic condition that has severe impacts on health and quality of life for those living with the illness.11–13 The disease manifests as chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain in different areas of the body.14–16 The need for information is greater due to the controversy surrounding the condition and a lack of specific diagnostics tests and evidence-based treatment guidelines. It has been suggested that people are often left on their own to manage the illness.17 16

Daraz and others studied the information needs and preferences of people living with fibromyalgia.8 9 The majority of patients in those studies expressed their preference for the web as a major source of fibromyalgia-related information. However, they also strongly expressed their concerns about the lack of some types of information about fibromyalgia (content), the need for evidence-based information (quality) and difficulty in understanding medical or technical terminologies (literacy/readability). A similar study by Crooks demonstrated that people living with fibromyalgia like to go online to access information about fibromyalgia to inform themselves about the illness and to assist with shared decision making with their healthcare providers.10 However, the perceived lack of quality of online information was a major factor that was also discussed in the study findings. Others have also suggested that web-based health information can increase people's perception of control, improve their ability to cope with illness, enhance their self-care abilities and improve their quality of life by decreasing anxiety, fear and distress while increasing hope.18 19 A number of studies have evaluated the quality of online health information designed for specific populations and found it to be of variable quality.20–25 2 26 It is imperative that people living with fibromyalgia have access to quality evidence-based information to help them live with their illness, especially since it is a chronic disease. Therefore, it is important to evaluate websites to determine if they can meet the needs of persons with fibromyalgia for accessible, high quality, useful information.

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the online information resources available for people living with fibromyalgia and to evaluate those information resources for content, quality and readability.

Methods

This study consisted of a keyword search, selection of websites and structured appraisal of the websites using standardised quality and readability tools. Similar methods were used by others who evaluated the quality of websites for specific conditions.20 21 24

Search strategies to find online fibromyalgia information resources

In a previous study, the authors identified search terms and engines that women commonly use when looking for information on fibromyalgia.8 Based on those findings, we performed a keyword search on Google (http://www.google.com) with the keyword ‘fibromyalgia’ on 11 December 2009 to identify the online fibromyalgia resources most likely to be accessed. It has been suggested that lay people seldom search for information beyond the first 20 links retrieved by a search engine, so we used this to dictate our website sample.27

Criteria for selecting online fibromyalgia information resources

Our inclusion criteria for selecting websites were: (1) provision of information on fibromyalgia, (2) provision of information for consumers/patients and their caregivers, and (3) provision of information in English. We excluded duplicate websites or sites with dead links.

Quality appraisal tools

DISCERN is a reliable and valid instrument used to assess the quality of written consumer health information which people can use without content expertise.28 29 The instrument was developed and evaluated by an expert panel and a group of health information providers and self-help members. DISCERN consists of 15 questions (the first eight questions are on publication reliability and last seven questions are on the quality of information on treatment choices) where each question is rated on a 1–5 point scale. We assigned scores according to the DISCERN marking system (topic addressed=5, partially addressed=3, not addressed=1). This instrument has been evaluated for reliability and validity and is being used by many researchers to assess the quality of online health information for specific diseases.20 23 24 However, DISCERN does not include many of the criteria that are important for assessing specific information content and the dissemination of the information, for example, accuracy, completeness, disclosure and readability.27

As a result, we used a quality checklist developed by Daraz and others30 to assess the quality of web health information. This tool was based on a structured review and appraisal of existing web health evaluation tools developed to assess the quality of web health information. Based on their review, the authors determined that the existing web health evaluation tools did not meet the criteria for readability and ease of use for general consumers. Therefore, they recommended a customised tool/quality checklist designed for general consumer use. The Quality Checklist consists of seven categories: (1) authorship, (2) content, (3) currency, (4) usefulness, (5) disclosure, (6) user support and feedback, and (7) privacy and confidentiality. A total of 10 questions are included in the checklist with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ option.

To determine the overall rating of the websites, we also used the total DISCERN score to categorise the websites as excellent (61–75), very good (60–46), good (45–31), marginal (30–16) or poor (15–1). It was not possible to assign similar categories to assess the overall rating of the websites using the Quality Checklist as the tool does not have a numerical scoring scheme.

For the readability evaluation, the information from each websites was evaluated for (1) reading ease and (2) grade level using the actual content from the website. For the reading ease calculation we used the Flesch Reading Ease31 32 score maps designed to measure the readability of texts; the reading index is 0–100. A score of around 60–70 is equivalent to grade level 6–8. The closer to 100 the text scores, the easier it is to read.31 33

We used the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level formula to calculate grade level. It is recommended that anyone who aims to provide health information should aim for a grade level of 6–8. The scores using the Flesch Reading Ease formula are explained in box 1.31 32

Box 1. Flesch Reading Ease scores.

90–100: Very easy

80–89: Easy

70–79: Fairly easy

60–69: Standard

50–59: Fairly difficult

30–49: Difficult

0–29: Very confusing

Data extraction and analysis

When the information on websites is consistent with the best research, then that information is high quality and high quality websites are those which are constructed according to certain standards.34 20 35 By ‘content’ we mean to specific information about fibromyalgia, for example, on treatment, diet, finding specialists, etc. By ‘readability’, we mean reading ease and grade level. By ‘quality’ we mean overall website quality, not the quality of specific pieces of information on the website: website quality assesses the efforts made to insure the information on the website is current and accurate based on current evidence/knowledge.

A data extraction tool was devised to allow reviewers to categorise the content on fibromyalgia websites. Categories were developed using concepts derived from both qualitative and quantitative research8 9; open-ended categories were later classified if concepts were reported that were not preconceived by the structured items. The data extraction table included: country of origin, target audience, category of websites and types of content. Websites were categorised as not-for-profit (eg, society, association, charitable group, support group), commercial (eg, private medical site, sponsored site), media (eg, newspaper) and institutional (eg, university, government).

To assess the reliability of evaluation, each site was independently rated by the authors. Although κ scores were not tabulated, the reviewers discussed each question where scoring was different until the scoring conflict was resolved. We used simple descriptive statistics to analyse the data. SPSS v 18 was used in our analysis for calculating frequencies and cross-tabulations. For example, the frequency command was used to determine the percentiles of websites for country of origin or the categories of websites.

Results

Google retrieved 6 720 000 results for the keyword search. The first 25 websites were selected for analysis (table 1). Thirteen (52%) of the websites were from the USA, eight (32%) were from Canada, one was from the UK and the rest had no country specified (table 1). The category of websites varied. Ten (40%) were not-for-profit organisations, six (24%) were commercial, five (20%) were media and four (16%) were institutional. Only five (20%) websites were dedicated to women. Table 1 also gives the scores for DISCERN (column 3) and the percentage of ‘yes’ answers for the Quality Checklist (column 4).

Table 1.

25 Selected sites and their overall scores

| Website; URL | Developer/origin | DISCERN Totalscore - 75 | Quality checklist, % yes | Readability (grade level) |

| Fibromyalgia Treatment Center36; http://www.fibromyalgiatreatment.com/ | Fibromyalgia Treatment Center, Inc/USA | 22 | 80 | 7 |

| Fibromyalgia Network37; http://www.fmnetnews.com/ | Not specified/USA | 38 | 60 | 8 |

| Medline Plus38; http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus | National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health/USA | 40 | 80 | 8 |

| Women's Health Matters39; http://www.womenshealthmatters.ca | Women's College Hospital and the Women's College Research Institute/Canada | 46 | 80 | 8 |

| Body and Health40; http://bodyandhealth.canada.com | MediResource/Canada | 27 | 30 | 9 |

| The Environmental Illness Resource41; http://www.ei-resource.org/ | Matthew Hogg/UK | 32 | 70 | 9 |

| Fibromyalgia Support42; http://www.fibromyalgia-support.org | Global Healing Center/USA | 28 | 90 | 9 |

| FM-CFS Canada43; http://fm-cfs.ca/fm.html | FM-CFS Canada/Canada | 55 | 80 | 9 |

| Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia; http://en.wikipedia.org44 | Wikimedia Foundation, Inc/USA | 40 | 80 | 10 |

| Canadian Women's Health Network45; http://www.cwhn.ca | The Canadian Women's Health Network and the Centres of Excellence for Women's Health/Canada | 34 | 60 | 10 |

| MedicineNet.com46; http://www.medicinenet.com | MedicineNet, Inc/USA | 45 | 80 | 10 |

| Fibromyalgia Symptoms47; http://www.fibromyalgia-symptoms.org/http://www.fibromyalgiasymptoms.org/ | Not specified | 46 | 40 | 10 |

| About.com48; http://chronicfatigue.about.com | The New York Times Company/USA | 46 | 90 | 10 |

| Women and Fibromyalgia49; http://womenandfibromyalgia.com/ | Book written by Barbara Keddy/Canada | 23 | 60 | 10 |

| National Fibromyalgia Partnership50; http://www.fmpartnership.org/ | The National Fibromyalgia Partnership, Inc/not specified | 50 | 60 | 10 |

| Fibromyalgia Chronic Fatigue51; http://www.chronicfatigue.org/ | Clymer Healing Center/USA | 21 | 50 | 10 |

| Autoimmunity Research Foundation52; http://autoimmunityresearch.org/ | Autoimmunity Research Foundation/USA | 24 | 70 | 11 |

| Fibromyalgia Information53; http://fibromyalgia.ncf.ca/ | Woman to Woman Computing/Canada | 52 | 90 | 11 |

| Ontario Fibromyalgia Association54; http://www.hwcn.org/∼aq226/ (no longer active) | Not specified/Canada | 23 | 40 | 11 |

| NIAMS55; http://www.niams.nih.gov | National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/USA | 49 | 100 | 11 |

| Fibromyalgia Information Foundation56; http://www.myalgia.com/ | Oregon Health & Science University/USA | 51 | 90 | 11 |

| Fibrohugs57; http://fibrohugs.com/ | Ken Euteneier/not specified | 16 | 40 | 12 |

| Mayo Clinic58; http://mayoclinic.com/ | Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research/USA | 45 | 90 | 13 |

| BC Fibromyalgia Society59; http://www.mefm.bc.ca | MEFM Societies of BC/Canada | 28 | 70 | 13 |

| Neurology Channel60; http://www.neurologychannel.com | Healthcommunities.com, Inc/USA | 41 | 80 | 15 |

The list is based on lowest to highest readability scores.

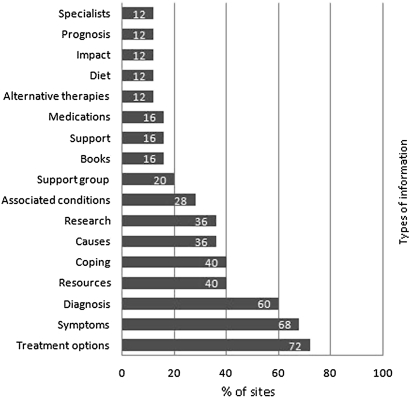

Figure 1 shows the types of information provided by the selected websites. Other types of information were also available on the selected websites, for instance on complications (8%), controversies (8%), exercise (8%), lifestyle (8%), education (4%), employment (4%), psychological issues (4%), quality of life (4%) and self-help (4%).

Figure 1.

Types of information available on selected websites.

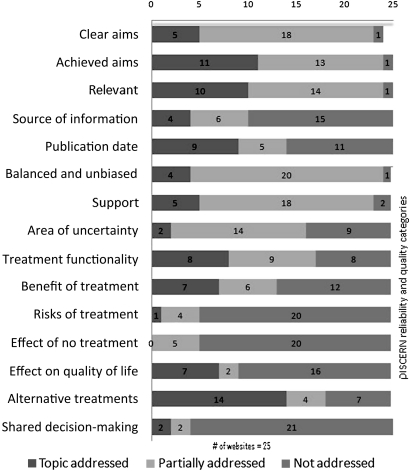

Figure 2 shows the reliability of the websites and the quality of treatment information as measured by DISCERN. The mean score of all 15 questions combined was 2.49 out of 5. No question received a mean score of 4 or more. The questions that received the lowest score were related to sources of information, areas of uncertainty, side effects of treatments, effects of no treatment, effect on quality of life and shared decision-making. Websites were categorised as very good (32%), good (32%) or marginal (36%). The mean overall DISCERN score was 36.88 (good).

Figure 2.

Combined scores of the DISCERN reliability and quality of treatment categories.

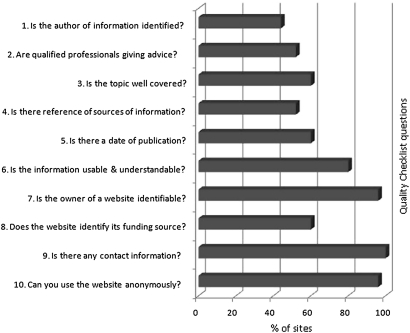

Figure 3 shows the combined Quality Checklist scores for the websites. The questions with the highest rating related to contact information, confidentiality, ownership and useable/understandable content.

Figure 3.

Combined scores of the Quality Checklist questions (percentage of option ‘yes’).

The readability test showed that the reading level for 14 (56%) websites was between grades 10 and 12, seven websites (28%) were between grades 8 and 9, and one website (4%) was between grades 6 and 7. None were between grade 1 and 5 and 12% were college level (table 1).

Table 2 shows the five highest ranked websites according to scores from DISCERN, the Quality Checklist and the Flesch Reading Ease test.

Table 2.

Five top ranked websites based on the DISCERN, Quality Checklist and Flesch Reading Ease scores

| Tool | Website |

| DISCERN |

|

| Quality checklist |

|

| Flesch Reading Ease |

|

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that fibromyalgia websites vary with respect to content, quality and readability. There is considerable variability between the average scores from DISCERN, the Quality Checklist and the Flesch Reading Ease test. Good quality websites often had poor readability. Only three websites (Fibromyalgia Information,53 Fibromyalgia Information Foundation56 and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases55) had consistently high levels of quality (table 1). Unfortunately, since these also had high reading levels (grade 11), they are not likely to be accessible by people with lower literacy.

The content of the websites most commonly addressed symptoms, treatment and diagnosis. Many websites lacked information about important topics identified by patients as significant, such as causes of fibromyalgia, research, supports, alternative therapies, impact, and specialists who might help them understand and manage their illness.8 9 61 More efforts are needed to include comprehensive information on the websites that provide customised information for people with fibromyalgia.

Quality scoring with the two quality appraisal tools resulted in different rankings for the same website due to different items and scoring systems. Others have shown that there is considerable variability in the critical appraisal tools used for evaluating research34 and it appears that a similar trend is evolving with respect to websites. While DISCERN seems to be the most commonly used tool, it is important for those conducting reviews to evaluate whether the critical appraisal tool used is the most appropriate one for their individual study.

This study focused on assessing the quality of a website from the perspective of a lay person.26 23 Lay ‘quality’ assessment assumes practices that indicate more rigorous development and authorship will lead to more timely and accurate information. That is because the general public cannot verify the accuracy of specific medical or scientific information on the web. This study indicates that websites do not adequately identify the sources or timeliness of the information presented. It has been suggested that providing a date does not necessarily mean that the information is correct or up-to-date.2 However, it is a reasonable proxy. Website currency could be judged by determining if recent evidence has been incorporated, but this is not a reasonable expectation for the lay public. Similarly, providing contact information may be associated with authors taking responsibility for their website, but there may be a variety of other motivations. This study focused on assessment of website quality from the perspective of the consumer. We also observed that two different tools (DISCERN and the Quality Checklist) designed for the lay public provided different scores and rankings. We have no way of knowing whether one tool provided a more valid assessment than the other. However, both scales agreed on three (Fibromyalgia Information,53 Fibromyalgia Information Foundation56 and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases55) out of five websites in the top five (table 2), suggesting a level of concurrent validity. Studies that assess the extent to which different lay indicators of quality are associated with actual quality and accuracy of information are needed to assess the criterion validity of these scales.

This review demonstrates that a substantial proportion of the most accessible fibromyalgia information websites do not meet the criteria established for website quality, thus undermining confidence in the accuracy of these resources. Healthcare providers and website developers should work together to provide more consistent information for people living with fibromyalgia. There is also a need to determine useful and accurate criteria for lay individuals to assess website quality. For example, none of the tools used for this study can assess websites for accessibility, linking, peer to peer feedback or web standards.

Another major finding of this review is that people need a high level of education to understand online information about fibromyalgia, particularly on high quality websites. For example, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases website provides good quality information about fibromyalgia; however, a person needs a grade level of 11 to understand and use that information. Only four websites (Fibromyalgia Treatment Center,36 Fibromyalgia Network,37 Medline Plus,38 Women's Health Matters39) meet the literacy level for the general population. High readability requirements decrease information accessibility and potentially exclude users with low literacy skills.62 Using the web to provide useable quality information remains elusive. A common concern among people living with chronic illnesses including fibromyalgia is that difficult medical terminology is a major barrier to accessing and using online health information efficiently.8 9 20 61 Online information on fibromyalgia needs to be written at or below a grade 8 level so that all are able to read the information and use it for their own health decision-making. This suggests that people with health literacy expertise should be involved in website development.

Overall, there is evidence that there are inconsistencies across websites regarding content, overall quality and readability, as found by those who evaluated websites for other chronic conditions.2 26 People living with fibromyalgia have expressed a strong need for information and a dependency on web-based information as a primary source. This indicates that more effort is needed to ensure that the information provided on fibromyalgia websites meets the information needs, quality and suggested readability criteria.

Limitations of the study

A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, our search was not comprehensive as we only used Google and one keyword to search for online fibromyalgia resources. We selected Google and ‘fibromyalgia’ as these were most commonly used by our target audience,8 but recognise that other search engines and keyword combination may have produced different results.

The way that items on the Quality Checklist are formatted also has some limitations. Since some items have multiple questions requiring a single yes/no answer, reviewers sometimes had difficulty selecting an option when partial credit was assigned. In addition, there is lack of evidence to validate the Quality Checklist. Thus, some of the differences between DISCERN and the Quality Checklist relate to scoring methods.

Finally, we have no gold standard for whether these websites were quality websites. We addressed the quality issue using two critical appraisal tools designed for the lay public. Some of the other important criteria such as accessibility, linking, web standards or peer-to-peer feedback, are not included in these quality tools. As a result, a detailed analysis of recommendations on websites would be required to determine whether they are consistent with the highest quality of evidence and therefore whether the information itself is also of high quality. Finally, the readability score may vary for some websites as it may be related to the use of technical terms such as fibromyalgia, since this seems to be a word with low readability.

Conclusion and implications for practice

The internet is changing the way that people gather information about chronic conditions like fibromyalgia and has the potential to facilitate patient self-management. This study has demonstrated that online fibromyalgia resources do not provide comprehensive information about fibromyalgia. The majority of the websites provide information on only a few content areas and are highly variable in terms of quality and readability. Website quality ranking varied by the tool used, although there was general agreement about the top three websites. Higher quality websites do not present information at language/reading levels appropriate for the general population. Thus, it is difficult for people with fibromyalgia to distinguish between good and poor online resources, suggesting the potential for misinformation. Healthcare and social service providers need to be aware of the general lack of quality of online fibromyalgia resources and need to be more involved in the health decision-making of people with fibromyalgia by helping them access quality online health information.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Daraz L, MacDermid JC, Wilkins S, et al. The quality of websites addressing fibromyalgia: an assessment of quality and readability using standardised tools. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000152. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000152

Funding: This work was supported by a Doctoral Research Award (Frederick Banting and Charles Best Scholarship) from the CIHR, a Strategic Training Fellowship in Rehabilitation Research from the CIHR Musculoskeletal and Arthritis Institute, an S. Leonard Syme Training Fellowship from the Institute for Work & Health and an MSK Training Fellowship from the Ontario Rehabilitation Research Advisory Network to Lubna Daraz.

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: The first author, LD was in charge of all aspects of research including choosing the topic, formulating research questions, reviewing the literature, designing the study, searching on Google, collecting data, evaluating websites, and drafting and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and provided final approval of the version to be published. JCMcD made substantial contributions to conception and design, evaluated websites, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. SW and JG made substantial contributions to conception and design, evaluated websites, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. LS made substantial contributions to conception and design, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Grandinetti DA. Doctors and the web: Help your patients surf the Net safely. Med Econ 2000;77:186–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman-Goetz L, Clarke NJ. Quality of breast cancer sites on the World Wide Web. Can J Public Health 2000;91:281–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sillence E, Briggs P, Harris P, et al. Going online for health advice: Changes in usage and trust practices over the last five years. Interact Comput 2007;19:397–406 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell RJ. Older women and the Internet. J Women Aging 2004;16:161–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandey S, Hart JJ, Tiwary S. Women's health and the internet: understanding emerging trends and implications. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:179–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Statistics Canada Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS). http://www.statcan.gc.ca/ (accessed 3 Feb 2011).

- 7.Fox S, Rainie L. The Social Life of Health Information. Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2009. http://www.pewinternet.org/∼/media//Files/Reports/2009/PIP_Health_2009.pdf (accessed 4 Feb 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daraz L. Information availability and needs of people with Fibromyalgia [dissertation]. Chapter 2. Hamilton, ON, Canada: McMaster University, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daraz L. Information availability and needs of people with Fibromyalgia [dissertation]. Chapter 3. Hamilton, ON, Canada: McMaster University, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crooks VA. I go on the Internet; “I always, you know, check to see what's new" chronically ill women's use of online health information to shape and inform doctor-patient interactions in the space of care provision. ACME: An Interna E-J Critical Geogra 2006;5:50–69 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weir PT, Harlan GA, Nkoy FL, et al. The incidence of fibromyalgia and its associated comorbidities: a population-based retrospective cohort study based on international classification of diseases, 9th revision codes. J Clin Rheumatol 2006;12:124–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaefer KM. The lived experience of fibromyalgia in African American women. Holist Nurs Prac 2005;19:17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunilla ML, Henriksson MC. Factors of Importance for work disability in women with fibromyalgia: an interview study. Arthritis Care Res 2002;47:266–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams DA, Clauw DJ. Understanding fibromyalgia: lessons from the broader pain research community. J Pain 2009;10:777–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann L, Buskila D. Epidemiology of Fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2003;7:362–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lempp HK, Hatch SL, Carville SF, et al. Patients' experiences of living with and receiving treatment for fibromyalgia syndrome: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kool MB, Middendorp HV, Boeije HR, et al. Understanding the lack of understanding: invalidation from the perspective of the patient with fibromyalgia. Arthr Rheum and Rheum 2009;61:1650–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor LR. Patients turn to Dr. Google for Health Information – Good and Bad. Journal staff. http://www.rapidcityjournal.com/lifestyles/article_32d777ca-ec1e-11de-aab5-001cc4c03286.html (accessed 22 Jan 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eysenbach G, Kohler C. How do consumers search for and appraise health information on the World Wide Web? Qualitative study using focus groups, usability tests, and in-depth interviews. BMJ 2002;324:573–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson AE, Graydon SL. Patient-oriented methotrexate information sites on the Internet: a review of completeness, accuracy, format, realiability, credibility, and readability. J Rheumatol 2009;36:41–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanif F, Abayasekara K, Willcocks L, et al. The quality of information about kidney transplantation on the World Wide Web. Clin Transplant 2007;21:371–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin-Facklam M, Kostrzewa M, Martin P, et al. Quality of drug information on the World Wide Web and strategies to improve pages with poor information quality. An intervention study on pages about sildenafil. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004;57:80–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khazaal Y, Fernandez MA, Cochand S, et al. Quality of web-based information on social phobia: a cross-sectional study. Depress Anxiety 2008;25:461–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hargrave DR, Hargrave UA, Bouffet E. Quality of health information on the Internet in pediatric neuro-oncology. Neuro Oncol 2006;8:175–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths KM, Christensen H. The quality and accessibility of Australian depression sites on the World Wide Web. Med J Aust 2002;176(10 Suppl):97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Bahrani A, Plusa S. The quality of patient-oriented internet information on colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2004;6:323–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eysenbach G, Powell J, Kuss O, et al. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the World Wide Web. A systematic review. JAMA 2002;287:2691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, et al. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:105–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shepperd S. DISCERN Online. Quality Criteria for Consumer Health Information. http://www.discern.org.uk/ (accessed 31 May 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daraz L, MacDermid JC, Wilkins S, et al. Tools to Evaluate the Quality of Web Health Information: A Structured Review of Content and Usability. Int J Tech Knowl Soc 2009;5:3 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colman MA. Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford University Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Flesch Reading Ease. Readability Formulas.com. Free Readability Assessment. http://www.readabilityformulas.com/free-readability-formula-assessment.php (accessed 22 Jan 2011).

- 33.D'Alessandro DM, Kingsley P, Johnson-West J. The readability of pediatric patient education materials on the World Wide Web. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:807–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katrak P, Bialocerkowski EA, Massy-Westropp N, et al. A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Med Res Methodol 2004;4:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jordan JE, Osborne RH, Buchbinder R. Critical appraisal of health literacy indices revealed variable underlying constructs, narrow content and psychometric weaknesses. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:366–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fibromyalgia Treatment Center http://www.fibromyalgiatreatment.com/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 37.Fibromyalgia Network http://www.fmnetnews.com/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 38.Medline Plus http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 39.Women's Health Matters http://www.womenshealthmatters.ca (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 40.Body and Health http://bodyandhealth.canada.com (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 41.The Environmental Illness Resource http://www.ei-resource.org (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 42.Fibromyalgia Support http://www.fibromyalgia-support.org (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 43.FM-CFS Canada http://fm-cfs.ca/fm.html (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 44.Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 45.Canadian Women's Health Network http://www.cwhn.ca/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 46.MedicineNet.com http://www.medicinenet.com (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 47.Fibromyalgia Symptoms. http://www.fibromyalgiasymptoms.org/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 48.About.com http://chronicfatigue.about.com (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 49.Women and Fibromyalgia http://www.myalgia.com/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 50.National Fibromyalgia Partnership http://www.fmpartnership.org/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 51.Fibromyalgia Chronic Fatigue. http://www.chronicfatigue.org/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 52.Autoimmunity Research Foundation http://bacteriality.com (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 53.Fibromyalgia Information. http://fibromyalgia.ncf.ca/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 54.Ontario Fibromyalgia Association http://www.hwcn.org (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 55.National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (NIAMSD) http://www.niams.nih.gov (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 56.Fibromyalgia Information Foundation http://www.myalgia.com/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 57.Fibro Hugs http://fibrohugs.com/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 58.Mayo Clinic http://mayoclinic.com/ (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 59.BC fibromyalgia Society http://www.mefm.bc.ca (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 60.Neurology channel http://www.neurologychannel.com (accessed 11 Dec 2009).

- 61.Murray E, Burns J, See J, et al. Interactive Health Communication Applications for people with chronic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD004274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Readability and cultural sensivity of web-based patient decision aids for cancer screening and treatment: a systematic review. Med Inform Internet Med 2007;32:263–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.