Abstract

There is no effective treatment for cocaine addiction despite extensive knowledge of the neurobiology of drug addiction1–4. Here we show that a selective aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH-2) inhibitor, ALDH2i, suppresses cocaine self-administration in rats and prevents cocaine- or cue-induced reinstatement in a rat model of cocaine relapse-like behavior. We also identify a molecular mechanism by which ALDH-2 inhibition reduces cocaine-seeking behavior: increases in tetrahydropapaveroline (THP) formation due to inhibition of ALDH-2 decrease cocaine-stimulated dopamine production and release in vitro and in vivo. Cocaine increases extracellular dopamine concentration, which activates dopamine D2 autoreceptors to stimulate cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) in primary ventral tegmental area (VTA) neurons. PKA and PKC phosphorylate and activate tyrosine hydroxylase, further increasing dopamine synthesis in a positive-feedback loop. Monoamine oxidase converts dopamine to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL), a substrate for ALDH-2. Inhibition of ALDH-2 enables DOPAL to condense with dopamine to form THP in VTA neurons. THP selectively inhibits phosphorylated (activated) tyrosine hydroxylase to reduce dopamine production via negative-feedback signaling. Reducing cocaine- and craving-associated increases in dopamine release seems to account for the effectiveness of ALDH2i in suppressing cocaine-seeking behavior. Selective inhibition of ALDH-2 may have therapeutic potential for treating human cocaine addiction and preventing relapse.

The lack of effective medication for cocaine addiction and relapse is a major unmet medical need5. Recent anecdotal clinical reports suggest that disulfiram may attenuate cocaine use6. Disulfiram, an irreversible nonspecific inhibitor of ALDH-1 and ALDH-2, increases acetaldehyde accumulation to discourage alcohol drinking, owing to the adverse effects of acetaldehyde. Reduced cocaine use after disulfiram treatment has been attributed to disulfiram inhibition of dopamine β hydroxylase (DBH) in the brain7. We and others have shown that highly selective ALDH-2 inhibitors potently reduce alcohol seeking in the presence or absence of acetaldehyde8,9. These findings seem to be explained by changes in dopamine metabolism. Thus, the selective ALDH-2 inhibitor ALDH2i (CVT-10216) prevents alcohol-induced increases in dopamine in the nucleus accumbens8, which is not explained by inhibition of DBH. Indeed, ALDH2i does not inhibit DBH (Supplementary Table 1). Taken together, these observations suggest that a selective inhibitor of ALDH-2 might suppress cocaine seeking by reducing drug-associated increases in dopamine synthesis. Here we test this possibility in vivo and in vitro.

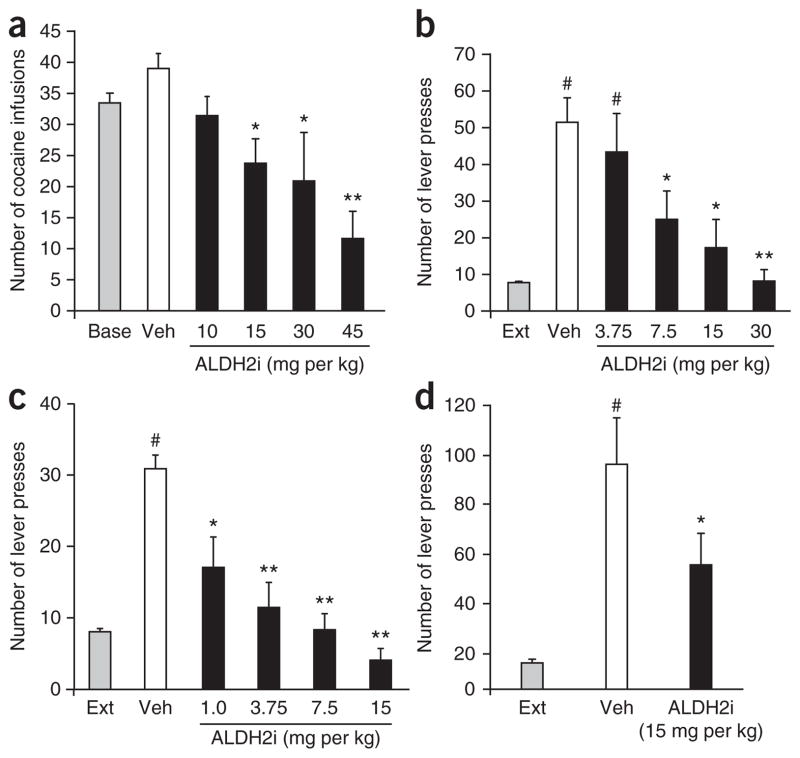

In a rat model of self-administration, ALDH2i inhibits intravenous cocaine infusions in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1a). Relapse is a serious limitation of effective medical treatment of cocaine addiction10,11. We therefore asked whether selective ALDH-2 inhibition can also prevent cocaine- or cue-induced cocaine relapse–like behavior in a reinstatement model. After rats deprived of cocaine extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior, we pretreated them with ALDH2i (intraperitoneally (i.p.)) 30 min before rechallenging with i.p. cocaine or auditory (tone) and visual (light) cues. ALDH2i dose dependently inhibits cocaine priming- or cue-induced reinstatement (Fig. 1b,c). Furthermore, ALDH2i also reduces methamphetamine-induced reinstatement in rats (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

ALDH2i reduces intravenous cocaine self-administration, cocaine-primed or cue-induced reinstatement and methamphetamine-induced reinstatement in Sprague Dawley rats. (a) The number of cocaine infusions recorded during the 2-h cocaine self-administration session (n = 7–12, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with vehicle (Veh)). (b,c) The number of lever presses recorded during the 2-h cocaine-primed (b) or cue-induced (c) reinstatement session (n = 6–9 and n = 6–11 for b and c, respectively; #P < 0.01 compared with extinction (Ext); **P < 0.01 compared with Veh). (d) The number of lever presses recorded during the 2-h methamphetamine-induced reinstatement session (n = 7, #P < 0.01 compared with Ext; *P < 0.05 compared with Veh).

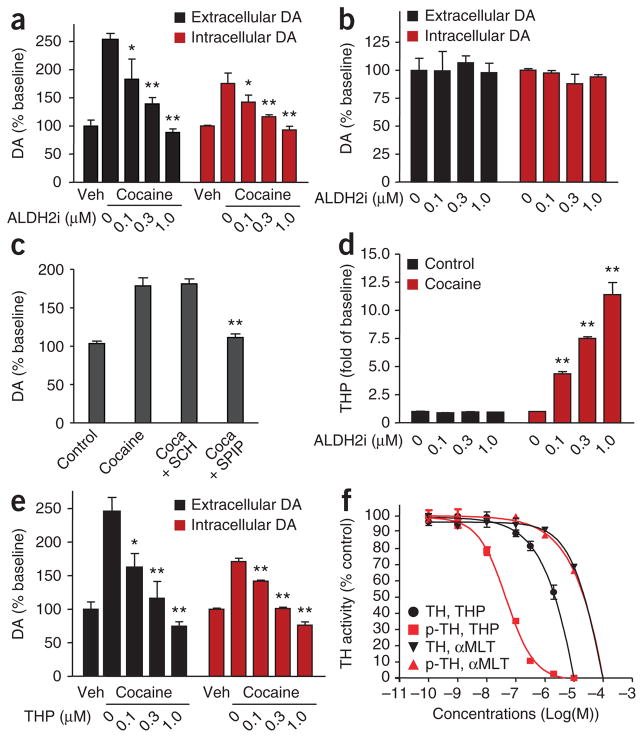

Dopamine is synthesized in VTA neurons and axonally transported for release in the nucleus accumbens12,13. Addictive drugs activate VTA neurons, leading to increased dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens14,15. We thus determined whether ALDH2i inhibits cocaine-induced dopamine production in PC12 cells, a neural cell line derived from a rat adrenal medullary pheochromocytoma. We find that cocaine elevates extracellular and intracellular dopamine levels (Fig. 2a). ALDH2i prevents cocaine-induced dopamine increases in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). Notably, ALDH2i had no effect on basal dopamine (Fig. 2b). Moreover, blockade of dopamine D2 receptors by the D2 antagonist spiperone prevented cocaine-induced increases in dopamine; the D1 antagonist SCH 23390 had no effect (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

ALDH2i decreases cocaine-induced dopamine (DA) production and increases THP abundance in PC12 cells. (a–e) Cells were incubated with or without cocaine (Coca, 1 μM) in the presence or absence of ALDH2i, the D1 antagonist SCH 23390 (SCH, 10 μM), the D2 antagonist spiperone (SPIP, 10 μM) or THP for 24 h. Intracellular and extracellular dopamine (a,b,e), total dopamine (c) or THP amounts (d) were determined. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with cocaine control. (f) Dose-response analysis of THP and α-methyl-L-tyrosine (αMLT) on the inhibition of total tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) or phosphorylated tyrosine hydroxylase (p-TH).

How does selective ALDH-2 inhibition block cocaine-induced increases in dopamine levels? ALDH-2 is highly expressed in dopaminergic neurons in the VTA and involved in downstream dopamine metabolism16. ALDH-2 converts DOPAL to 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl-acetic acid (DOPAC)17. Inhibition of ALDH-2 increases DOPAL concentration18, which condenses with dopamine to form THP19. We searched for evidence that selective inhibition of ALDH-2 induces THP formation during cocaine activation of dopamine production in PC12 cells. We found that ALDH2i increases THP formation in a dose-dependent manner in cocaine-treated cells (Fig. 2d). Of note, ALDH2i had no effect on basal THP abundance in the absence of cocaine (Fig. 2d). If ALDH2i-dependent formation of THP has a role in suppressing dopamine synthesis, then adding THP to cells should also inhibit dopamine synthesis. Indeed, we found that THP inhibits cocaine-stimulated dopamine production in cocaine-treated PC12 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2e) and reduces basal dopamine production20 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Tyrosine hydroxylase is the first and rate-limiting step in dopamine production. TH converts L-tyrosine to L-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), a substrate DOPA decarboxylase to yield dopamine17. Inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase, DOPA decarboxylase or both would be expected to lower dopamine synthesis. Therefore, we asked whether THP inhibits enzymes required for dopamine synthesis. We found that THP inhibited basal tyrosine hydroxylase activity with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration of 3.8 μM (Fig. 2f); dopamine decarboxylase was not affected (Supplementary Table 1).

Phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase dramatically increases tyrosine hydroxylase activity21. We determined whether THP inhibits the phosphorylated (activated) form of tyrosine hydroxylase more effectively than unphosphorylated enzyme. THP inhibited phosphorylated tyrosine hydroxylase enzyme activity with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration of 50 nM. Activated tyrosine hydroxylase is 75 times more sensitive to THP inhibition than unphosphorylated tyrosine hydroxylase (Fig. 2f). Unlike THP, the classic tyrosine hydroxylase inhibitor, α-methyl-L-tyrosine, was equally effective against tyrosine hydroxylase and phosphorylated tyrosine hydroxylase (Fig. 2f). THP did not inhibit the activities of other enzymes involved in dopamine metabolism, including DBH, monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), MAO-B and ALDH-2. ALDH2i by itself had no effect on these enzymes other than ALDH-2 (Supplementary Table 1).

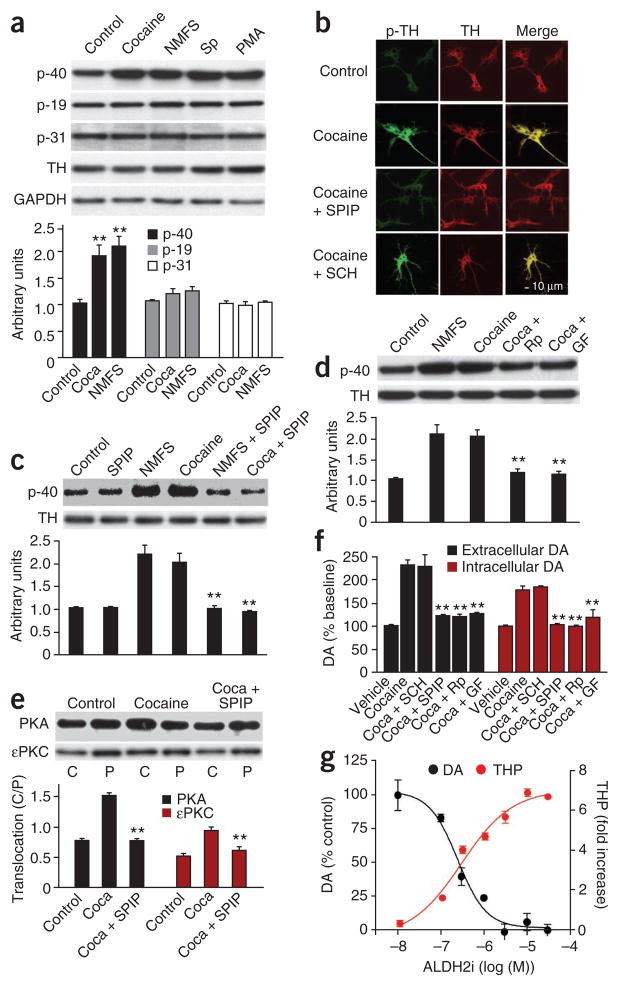

Tyrosine hydroxylase is activated by phosphorylation at Ser19, Ser31 and Ser40 (ref. 21). We asked whether cocaine activates dopamine synthesis by increasing tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation in primary VTA neurons. Western blotting showed that cocaine increases phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase mainly at Ser40, with little or no effect at Ser19 and Ser31 (Fig. 3a). As a positive control we tested nomifensine, another dopamine reuptake inhibitor, and found that it produced similar changes in tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation (Fig. 3a). Immunostaining of VTA neurons confirmed that cocaine increases tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation at Ser40 (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Cocaine activates PKA and PKC to phosphorylate tyrosine hydroxylase and increase dopamine production in VTA neurons. (a–e) Cells were incubated for 24 h with or without cocaine (1 μM) or nomifensine (NMFS, 10 μM) in the presence or absence of the PKA activator Sp-cAMPS (Sp, 1 mM, 10 min), the PKC activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 100 nM, 10 min), the D1 antagonist SCH23390 (10 μM), the D2 antagonist spiperone (10 μM), the PKA inhibitor Rp-cAMPS (Rp, 20 μM) or the PKC inhibitor GF 109203X (GF, 1 μM). TH phosphorylation at Ser40 p-40; (a–d), at Ser19 (p-19) and Ser31 (p-31; a) or the translocation of PKA and εPKC (e) was detected by western blotting (a,c–e) or by immunostaining (b). Green indicates phosphorylated tyrosine hydroxylase at Ser40 (p-TH), red, total tyrosine hydroxylase and yellow, the merged images. C/P, the ratio of PKA or ePKC in the cytosolic fraction (C) versus the particulate fraction (P). (f,g) Intracellular and extracellular dopamine (f) or total dopamine and THP (g). **P < 0.01 compared with sham or cocaine control.

VTA neurons express dopamine autoreceptors22–24. We asked whether dopamine receptors in VTA neurons are involved in cocaine-induced phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine production. Pretreatment of VTA neurons with the D2 antagonist spiperone completely blocked cocaine-induced tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation (Fig. 3b,c). In contrast, the D1 antagonist SCH23390 had no effect (Fig. 3b). These results suggest that D2 autoreceptors mediate phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase in VTA primary neurons.

Tyrosine hydroxylase is a substrate for PKA and PKC21. As expected, activation of PKA by Sp-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate (Sp-cAMPS) or activation of PKC by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate mimics cocaine-induced phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase in primary VTA neurons (Fig. 3a). By contrast, selective inhibition of PKA by Rp-cAMPS or PKC by GF109203X prevented cocaine-induced tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation at Ser40 (Fig. 3d). Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase by U-0126 or Ca2+-calmodulin–dependent protein kinase by KN-93 had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 2). Activation of D2 stimulates PKA and PKC25. Western blotting showed that cocaine induces translocation (activation) of PKA Cα and εPKC from the particulate fraction to the cytosol (Fig. 3e). Notably, translocation is blocked by the specific D2 antagonist spiperone (Fig. 3e), suggesting that cocaine-induced stimulation of D2 autoreceptors activates PKA and PKC signaling. Indeed, the PKA inhibitor Rp-cAMPS, the PKC inhibitor GF109203X and the D2 antagonist spiperone each blocked cocaine-induced increases in dopamine production in primary VTA neurons (Fig. 3f). Furthermore, we confirmed ALDH2i concomitantly increased THP and reduced dopamine concentrations in cocaine-treated VTA neurons (Fig. 3g).

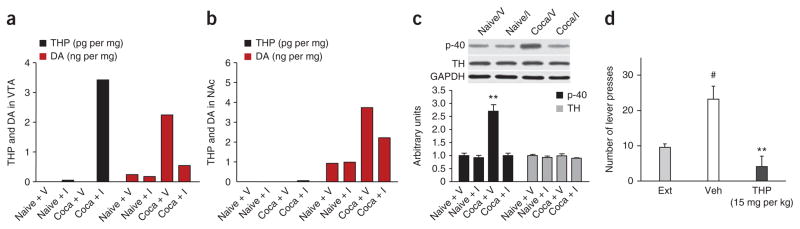

To confirm and extend our findings on the central role of THP in the mechanism of action of ALDH2i during cocaine addiction, we measured THP and dopamine abundance in vivo in the VTA and nucleus accumbens after rats extinguished from cocaine-seeking underwent auditory (tone) and visual (light) cue-induced reinstatement (Fig. 1c). Cue-induced rats showed large increases in dopamine abundance in the VTA (Fig. 4a) and nucleus accumbens (Fig. 4b), consistent with previous reports26. THP was virtually undetectable in nucleus accumbens (Fig. 4b). In contrast, cocaine-extinguished rats pretreated with ALDH2i (15 mg per kg body weight i.p.) before exposure to cues showed marked increases in THP in the VTA (Fig. 4a) and decreases in dopamine abundance in the VTA and nucleus accumbens (Fig. 4a,b). This correlated with considerable in vivo decreases in tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation by ALDH2i in VTA (Fig. 4c) and suppression of cocaine-seeking behavior (Fig. 1c). THP was virtually absent in the VTA or nucleus accumbens in naive rats that had never been given cocaine (Fig. 4a,b). Of note, ALDH2i does not affect basal dopamine levels in both brain regions (Fig. 4a,b). To support the hypothesis that THP has a role in ALDH2i suppression of cocaine-seeking behavior, we pretreated cocaine-extinguished rats with THP (15 mg per kg body weight i.p.) 30 min before exposure to cues. THP eliminated cue-induced reinstatement of lever-pressing for cocaine (Fig. 4d). These results may be compared to the diverse effects of THP on alcohol intake under various experimental conditions. THP augments voluntary alcohol consumption when given by intracerebroventricular injection but reduces alcohol intake when injected into striatal sites such as the VTA and substantia nigra complex27.

Figure 4.

ALDH2i increases THP production to inhibit tyrosine hydroxylase activity and decrease dopamine production in VTA in cocaine-addicted rats. (a,b) Dopamine and THP amounts measured in the VTA (a) and nucleus accumbens (b) pooled from the cocaine-seeking rats treated with ALDH2i (I, 15 mg per kg body weight, n = 8) or vehicle (V, n = 8) in Figure 1c or from naive rats treated with ALDH2i (15 mg per kg body weight, n = 8) or vehicle (n = 8). The experiment was repeated with similar results. (c) Tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation at Ser40 in the VTA, as detected by western blotting. **P < 0.01 compared with naive vehicle control. (d) The number of lever presses during the 2-h cue-induced cocaine reinstatement session (n = 8, #P < 0.01 compared with extinction; **P < 0.01 compared with Veh).

Our major findings suggest that selective inhibition of ALDH-2 by ALDH2i suppresses cocaine self-administration and prevents cocaine- or cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. ALDH-2 inhibition during activation of dopamine signaling diverts accumulating DOPAL to condense with dopamine to form THP. THP seems to inhibit cocaine- or cue-dependent increases in dopamine synthesis in the VTA via negative feedback inhibition of phosphorylated tyrosine hydroxylase. A putative molecular mechanism by which ALDH2i restores dopamine homeostasis is illustrated in Supplementary Figure 3.

There is extensive evidence that dopamine transmission from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens has a central role in cocaine addiction28–30. Activation of D2 autoreceptors in the VTA31 enhances dopamine neuron pacemaker activity32. D2 inhibition blocks reinforcing effects of addictive drugs33,34. But, there might be a limited margin of selectivity in blocking psychostimulant-induced effects compared with normal behaviors35,36. Notably, ALDH2i only interferes with cocaine-related increases in dopamine signaling and does not change basal levels of dopamine in the VTA and nucleus accumbens. This is consistent with our observation that ALDH2i does not affect inactive lever responses (Supplementary Table 2), locomotor activity, water intake and food consumption8. Moreover, we find no evidence of an additive effect of ALDH2i on cocaine self-administration (Supplementary Fig. 4). Although additional cocaine-seeking models can be used to extend our results, we believe our findings taken together demonstrate a new mechanism of action for ALDH-2 inhibition of dopamine production in the VTA and release in nucleus accumbens during cocaine seeking and in a rat model of cocaine relapse–like behavior. We propose that a safe, selective, reversible ALDH-2 inhibitor such as ALDH2i may have the potential to attenuate human cocaine addiction and prevent relapse.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturemedicine/.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W.M. Keung for valuable discussions, G. Koob and M. Miles for critical reading of the manuscript, A. Dinkins and K. Wischerath for animal training and D. Soohoo for preparation of the ALDH2i formulation.

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available on the Nature Medicine website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.Y. and I.D. designed and supervised the project, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. P.F. designed, carried out and analyzed molecular and cell biology studies. M.A. designed, performed and analyzed behavioral studies. Z.J. performed the cell biology experiments. M.F.O. carried out cocaine dose-response experiments. J.Z. and team synthesized CVT-10216. K.L. supervised and H.-L.S. and N.C. performed mass spectrometric analysis of in vitro dopamine and THP. J.L. and H.-Y.K. developed a mass spectrometric analysis method for dopamine and THP and determined their in vivo abundance. J.S. contributed to design and review of PC12 data. B.B. contributed to design and review of in vivo data.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/.

References

- 1.Koob GF, Kenneth Lloyd G, Mason BJ. Development of pharmacotherapies for drug addiction: a Rosetta stone approach. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:500–515. doi: 10.1038/nrd2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalivas PW. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:561–572. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1445–1449. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkow ND, Li TK. Drug addiction: the neurobiology of behaviour gone awry. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:963–970. doi: 10.1038/nrn1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sofuoglu M, Kosten TR. Emerging pharmacological strategies in the fight against cocaine addiction. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2006;11:91–98. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suh JJ, Pettinati HM, Kampman KM, O’Brien CP. The status of disulfiram: a half of a century later. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:290–302. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000222512.25649.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaval-Cruz M, Weinshenker D. Mechanisms of disulfiram-induced cocaine abstinence: antabuse and cocaine relapse. Mol Interv. 2009;9:175–187. doi: 10.1124/mi.9.4.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arolfo MP, et al. Suppression of heavy drinking and alcohol seeking by a selective ALDH-2 inhibitor. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1935–1944. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keung WM, Lazo O, Kunze L, Vallee BL. Daidzin suppresses ethanol consumption by Syrian golden hamsters without blocking acetaldehyde metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8990–8993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bossert JM, Ghitza UE, Lu L, Epstein DH, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: an update and clinical implications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyman SE, Malenka RC. Addiction and the brain: the neurobiology of compulsion and its persistence. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:695–703. doi: 10.1038/35094560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron. 1998;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wise RA. Brain reward circuitry: insights from unsensed incentives. Neuron. 2002;36:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balter M. New clues to brain dopamine control, cocaine addiction. Science. 1996;271:909. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berke JD, Hyman SE. Addiction, dopamine and the molecular mechanisms of memory. Neuron. 2000;25:515–532. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCaffery P, Drager UC. High levels of a retinoic acid–generating dehydrogenase in the meso-telencephalic dopamine system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7772–7776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenhofer G, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Catecholamine metabolism: a contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:331–349. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamensdorf I, et al. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde potentiates the toxic effects of metabolic stress in PC12 cells. Brain Res. 2000;868:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchitti SA, Deitrich RA, Vasiliou V. Neurotoxicity and metabolism of the catecholamine-derived 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde: the role of aldehyde dehydrogenase. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:125–150. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YM, Kim MN, Lee JJ, Lee MK. Inhibition of dopamine biosynthesis by tetrahydropapaveroline. Neurosci Lett. 2005;386:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunkley PR, Bobrovskaya L, Graham ME, von Nagy-Felsobuki EI, Dickson PW. Tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation: regulation and consequences. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1025–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brodie MS, Dunwiddie TV. Cocaine effects in the ventral tegmental area: evidence for an indirect dopaminergic mechanism of action. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1990;342:660–665. doi: 10.1007/BF00175709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen SY, Burger RI, Reith ME. Extracellular dopamine in the rat ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens following ventral tegmental infusion of cocaine. Brain Res. 1996;729:294–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacey MG, Mercuri NB, North RA. Actions of cocaine on rat dopaminergic neurones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;99:731–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12998.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao L, et al. Dopamine and ethanol cause translocation of epsilonPKC associated with epsilonRACK: cross-talk between cAMP-dependent protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling pathways. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1105–1112. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuber GD, et al. Reward-predictive cues enhance excitatory synaptic strength onto midbrain dopamine neurons. Science. 2008;321:1690–1692. doi: 10.1126/science.1160873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers RD. Anatomical ‘circuitry’ in the brain mediating alcohol drinking revealed by THP-reactive sites in the limbic system. Alcohol. 1990;7:449–459. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sombers LA, Beyene M, Carelli RM, Wightman RM. Synaptic overflow of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens arises from neuronal activity in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1735–1742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5562-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nestler EJ. The neurobiology of cocaine addiction. Sci Pract Perspect. 2005;3:4–10. doi: 10.1151/spp05314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts DC, Koob GF. Disruption of cocaine self-administration following 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the ventral tegmental area in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17:901–904. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickinson SD, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor–deficient mice exhibit decreased dopamine transporter function but no changes in dopamine release in dorsal striatum. J Neurochem. 1999;72:148–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hahn J, Kullmann PH, Horn JP, Levitan ES. D2 autoreceptors chronically enhance dopamine neuron pacemaker activity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5240–5247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4976-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Negus SS, Mello NK, Lamas X, Mendelson JH. Acute and chronic effects of flupenthixol on the discriminative stimulus and reinforcing effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:879–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rassnick S, Pulvirenti L, Koob GF. Oral ethanol self-administration in rats is reduced by the administration of dopamine and glutamate receptor antagonists into the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;109:92–98. doi: 10.1007/BF02245485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saeedi H, Remington G, Christensen BK. Impact of haloperidol, a dopamine D2 antagonist, on cognition and mood. Schizophr Res. 2006;85:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tinsley RB, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor knockout mice develop features of Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:472–484. doi: 10.1002/ana.21716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.