Abstract

Leptin, discovered through positional cloning 15 years ago, is an adipocyte-secreted hormone with pleiotropic effects in the physiology and pathophysiology of energy homeostasis, endocrinology, and metabolism. Studies in vitro and in animal models highlight the potential for leptin to regulate a number of physiological functions. Available evidence from human studies indicates that leptin has a mainly permissive role, with leptin administration being effective in states of leptin deficiency, less effective in states of leptin adequacy, and largely ineffective in states of leptin excess. Results from interventional studies in humans demonstrate that leptin administration in subjects with congenital complete leptin deficiency or subjects with partial leptin deficiency (subjects with lipoatrophy, congenital or related to HIV infection, and women with hypothalamic amenorrhea) reverses the energy homeostasis and neuroendocrine and metabolic abnormalities associated with these conditions. More specifically, in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea, leptin helps restore abnormalities in hypothalamic-pituitary-peripheral axes including the gonadal, thyroid, growth hormone, and to a lesser extent adrenal axes. Furthermore, leptin results in resumption of menses in the majority of these subjects and, in the long term, may increase bone mineral content and density, especially at the lumbar spine. In patients with congenital or HIV-related lipoatrophy, leptin treatment is also associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity and lipid profile, concomitant with reduced visceral and ectopic fat deposition. In contrast, leptin's effects are largely absent in the obese hyperleptinemic state, probably due to leptin resistance or tolerance. Hence, another emerging area of research pertains to the discovery and/or usefulness of leptin sensitizers. Results from ongoing studies are expected to further increase our understanding of the role of leptin and the potential clinical applications of leptin or its analogs in human therapeutics.

Keywords: adipokines, adipose tissue, leptin resistance, leptin deficiency, hypoleptinemia

studies of genetically obese mice serendipitously found in the Jackson Laboratories revealed that their phenotypes derive from homozygous mutations of either the obese (ob) or diabetic (db) genes that result in obesity and insulin resistance or diabetes as well as endocrine and immune dysfunction (53, 54, 115, 117, 183, 261). The gene mutation in the ob/ob mouse results in a complete deficiency of or a truncated and biologically inactive ob gene product (287); the latter subsequently was given the name leptin (95), from the Greek word “leptos” (meaning “thin”), because when this protein was given to the obese ob/ob mice they lost significant amounts of body weight. It was then recognized that the db gene codes for the leptin receptor (140). Consequently, exogenously administered leptin reduces body weight and resolves the metabolic, endocrine, and immune disturbances in ob/ob mice but has no effects in db/db mice (100, 111, 287). In the 15 years following these initial observations, a series of studies have been carried out, and over 19,000 papers on leptin published in Medline have considerably increased our knowledge regarding the biology of leptin and its role in human endocrinology and metabolism. In this review, we focus on the role of leptin in regulating neuroendocrine function, insulin sensitivity, immune function, and bone metabolism and highlight the role of leptin in the pathophysiology and therapeutics of human disease.

LEPTIN IN HUMAN PHYSIOLOGY

Leptin is a 167-amino acid peptide with a four-helix bundle motif similar to that of a cytokine (24, 286). Leptin is produced predominantly in the adipose tissue but is also expressed in a variety of other tissues, including placenta, ovaries, mammary epithelium, bone marrow, and lymphoid tissues (178). Leptin binds to leptin receptors (ObRs) located throughout the central nervous system and peripheral tissues (71), with at least six receptor isoforms identified (ObRa, ObRb, ObRc, ObRd, ObRe, and ObRf) (140). These have homologous domains, but, due to alternative mRNA splicing, each receptor has a unique sequence and length (140, 258). The short isoforms ObRa and ObRc are thought to have important roles in transporting leptin across the blood-brain barrier (15, 105). The long isoform ObRb is ubiquitously expressed throughout the central nervous system and is primarily responsible for leptin signaling (15, 140, 258). The ObRb receptor is particularly important in the hypothalamus, where it regulates energy homeostasis and neuroendocrine function (65, 71, 79). In the db/db mouse model, the ObRb receptor is mutated and dysfunctional, resulting in the obese diabetic phenotype (274). The soluble leptin receptor isoform ObRe is the extracellular cleaved part of the long isoform ObRb and the main circulating leptin-binding protein (108) and may antagonize leptin transport by inhibiting surface binding and endocytosis of leptin (264).

In humans, the release of leptin into the circulation is pulsatile, and leptin concentrations follow a circadian rhythm (233), are affected by sleep patterns (196, 85), and display highest levels between midnight and early morning and lowest levels in the early to mid-afternoon (16, 149, 248). The pulsatile nature of leptin's secretion pattern (243) is similar in obese and lean individuals, but the obese have higher pulse amplitudes (16, 149, 248) and overall greater leptin concentrations than lean subjects due to their greater amount of body fat (57, 282). Furthermore, for the same age and body mass index (BMI), women have greater leptin concentrations than men (174). Leptin concentrations in women may be higher in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (8, 64, 157), whereas menopause is associated with a decline in circulating leptin (131). Renal failure also results in higher leptin levels (163). These observations suggest that sex differences in leptin concentration are likely also the result of differences in sex hormones, e.g., estrogen and testosterone (35, 153, 245), besides those in body fat mass and/or distribution (131, 137, 188, 194, 224, 229).

Progressive fasting results in a rapid decline in leptin concentration, which occurs before any loss of fat mass (20), thereby triggering an adaptive mechanism to conserve energy (37). In mice and humans, the neuroendocrine response to food deprivation includes decreasing reproductive hormone concentrations (thereby reducing fertility and preventing pregnancy) (38, 165, 194), decreasing thyroid hormone concentrations (thereby slowing metabolic rate), increasing growth hormone (GH) concentration (thereby mobilizing energy stores), and decreasing insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) concentration (thereby slowing energy-demanding growth-related processes) as well as increasing adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol (3, 184, 268).

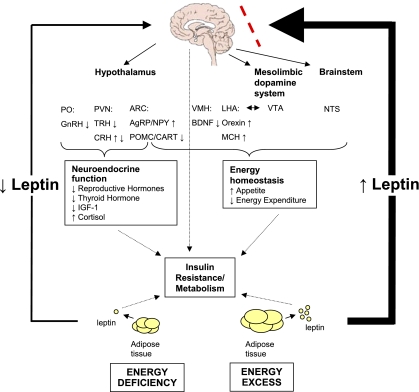

To assess the role of leptin in regulating the neuroendocrine response to fasting in humans, we first performed studies on the pharmacokinetics of leptin in humans and determined the doses required to achieve specific levels of circulating leptin in blood (45, 46, 278). We then studied healthy volunteers in the fed (141) and fasting states (37, 40). In acutely energy-deprived lean men (i.e., fasted for 3 days) we observed a fall in leptin concentration concomitant with a spectrum of neuroendocrine abnormalities; most of these abnormalities were reversed with physiological replacement doses of leptin (37). In particular, leptin replacement during fasting prevented the starvation-induced changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and, in part, the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and IGF-I binding capacity in serum but did not reverse the changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis at an appreciable level and/or the renin-aldosterone system, and GH/IGF-I axes (37). We also found similar neuroendocrine abnormalities in normal-weight women after caloric deprivation; however, replacement doses of leptin only modestly restored the changes in luteinizing hormone (LH) pulsatility and did not affect any other neuroendocrine axes (40). A major difference between these studies was the extent of the fall in leptin concentrations during fasting. In the former study on lean men, leptin concentration dropped from 2.24 ng/ml to clearly hypoleptinemic levels of 0.27 ng/ml (37). In contrast, in the latter study on normal-weight women, leptin concentration fell from 14.7 ± 2.6 ng/ml to low physiological levels of 2.8 ± 0.3 ng/ml (40). These data suggest that there may be a leptin threshold necessary for leptin's regulation of the hypothalamic-pituary-peripheral axes (170) (167). We thus proposed that the discrepancies between these two studies were due to leptin's permissive role in regulating neuroendocrine function, and we put forth the hypothesis that leptin replacement exerts a physiologically important effect only when the circulating leptin concentration falls below a certain threshold (Fig. 1). This apparently has important implications in states of energy deficiency such as anorexia nervosa, lipoatrophy, and/or strenuously exercising athletes who are in negative energy balance (9, 123, 161, 162, 164). We will review below the results from several studies on the effects of leptin on physiological functions in these disease states supporting this notion.

Fig. 1.

States of energy excess are associated with hyperleptinemia, but the hypothalamus is resistant or tolerant to the effects of increased leptin (dashed line). Energy deficiency results in hypoleptinemia. As a result, a complex neural circuit comprising orexigenic and anorexigenic signals is activated to increase food intake (220). In response to decreased leptin levels, there is increased expression of orexigenic neuropeptides AgRP and NPY in the ARC (59) and orexin and MCH in the LHA. Furthermore, there is decreased expression of anorexigenic neuropeptides POMC and CART in the ARC (59) and BDNF in the VMH. In addition to neurons that project from the LHA to the VTA, leptin also acts at the VTA of the mesolimbic dopamine system to regulate motivation for and reward of feeding. Leptin activation of the NTS of the brain stem also contributes to satiety. In addition, leptin has direct and/or downstream effects on the PVN and PO that are important for neuroendocrine responses to energy deprivation, including reducing reproductive and thyroid hormones. For the sake of comparison, leptin acts only indirectly on the GnRH-secreting neurons in the hypothalamus, and it can act directly and indirectly on TRH-secreting neurons (220). The effect of leptin on cortisol levels during starvation differs in mice and humans. Unlike in normal mice (102), leptin administration does not reverse the elevated adrenocorticotropin levels associated with starvation in humans (37). The mechanism of leptin's effect on the growth hormone axis is unclear. Dashed arrows indicate how leptin directly and indirectly influences metabolism and insulin resistance. AgRP, agouti-related protein; ARC, arcuate nucleus; BDNF, brain-derived neurotropic factor; CART, cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor I; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; MCH, melanin-concentrating hormone; NPY, neuropeptide Y; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; PO, preoptic area; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; TRH, thyrotropin-releasing hormone; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Physiological Role of Leptin in the Regulation of Neuroendocrine Function

Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.

Although leptin has been shown to stimulate LH secretion in rodents both in vitro and in vivo (285), hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons do not express ObRb (72, 94, 217). Therefore, leptin must regulate the reproductive axis via indirect mechanisms. Recent studies have indicated that leptin regulates reproductive function by activating neurons that project afferent input to GnRH neurons in the preoptic area and other hypothalamic areas (106). Several neurons involved in energy homeostasis are anatomically associated with GnRH neurons [e.g., agouti-related peptide/neuropeptide Y (AgRP/NPY) and proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons] and may thus link changes in energy balance with subsequent alterations in reproductive function (106). There is also evidence suggesting that leptin may mediate the reproductive axis through regulation of kisspeptins, products of the Kiss1 gene, as well as dynorphin and neurokinin B. Mutations causing dysfunction of the kisspeptin receptor gene GPR54 results in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in both mice and humans (61, 236), and various kisspeptins have been shown to stimulate the release of GnRH and increase plasma levels of LH, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and total testosterone in vivo in animals (91, 118, 240, 260). Approximately 40% of KiSS-1 mRNA-expressing cells in the arcuate nucleus coexpress ObRb mRNA (249). Moreover, ob/ob mice have lower levels of KiSS-1 mRNA than wild-type mice, and when ob/ob mice are treated with leptin, levels of KiSS-1 mRNA increase, suggesting that the reproductive dysfunction associated with leptin deficiency may be partially due to subnormal levels of kisspeptins (249). Similarly, human mutations in the gene encoding neurokinin B or its receptor lead to defective GnRH release and subsequent hypogonadism (145). Furthermore, a subpopulation of neurons in the arcuate nucleus coexpress kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin, another peptide that is implicated in the feedback regulation of GnRH neurons (145). These neurons also contain leptin receptors (249) and may thus mediate the effects of nutritional status and stress on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (145). There is, in fact, compelling evidence from basic and clinical studies indicating that leptin is an important mediator of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (150), even though the exact brain areas and molecular mechanisms involved remain to be fully elucidated (106).

Ob/ob mice are infertile, and their fertility can be restored with exogenous leptin administration independently of weight loss (47). Similarly to humans, in otherwise healthy but acutely energy-deprived rodents, fasting results in decreased gonadotropin pulsatility and secretion and blunts reproductive function (3). Leptin administration to these rodents normalizes LH levels and the estrous cycle in females and restores testosterone levels in males (3). Similarly, a crucial permissive role for leptin in human reproductive function was confirmed by our study of caloric deprivation with leptin replacement in healthy volunteers studied in our General Clinical Research Center. We showed that caloric deprivation blunts LH pulsatility and testosterone secretion in healthy lean men and that leptin replacement can restore these hormones to prefasting baseline levels (37). In normal-weight women, caloric deprivation decreases LH peak frequency, which is also fully corrected with leptin replacement (40). We then studied whether leptin's regulation of the hypothalamic-pituary-gonadal axis could possibly play a role in the initiation of puberty, since R. Frisch had long suggested (76) that puberty in girls occurs when a certain amount of body weight is attained. We found in the context of longitudinal observational studies that rising leptin levels are associated with the onset of puberty in normal boys (166, 171). Sex differences in leptin levels during and after puberty are related to differences in subcutaneous fat depots and sex steroid levels (151, 221). Administration of leptin has resulted in increased circulating LH levels in a young prepubertal boy with leptin deficiency (66) and induced phenotypic and hormonal changes consistent with puberty in adults with congential leptin deficiency who had remained prepubertal (148). These findings extend similar observations in mice (2) and provide experimental evidence that normal leptin levels may have a permissive role and thus be necessary for normal progression of puberty and reproductive maturity.

Hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis.

Leptin influences the thyroidal axis by regulating the expression of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) (230). In vitro and in vivo studies in rodents have shown that leptin directly stimulates TRH-expressing neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus to upregulate proTRH gene expression (144). Leptin also indirectly influences TRH neurons in the PVN through signals from the arcuate nucleus, as melanocortins (induced by leptin) stimulate and AgRP (suppressed by leptin) inhibits the thyroid axis (133, 211). Leptin also blunts the fasting-induced decrease in prohormone convertase-1 and -2 (PC1 and PC2), which cleave TRH from proTRH (230).

Leptin deficiency in the ob/ob mouse is associated with hypothalamic hypothyroidism from birth (266). Normal mice experience a drop in thyroxine concentration with fasting-induced hypoleptinemia (3) due to rapid suppression of TRH expression in the PVN, leading to decreased thyroxine and triiodothyronine concentrations (74). Leptin replacement reverses these changes (3).

In healthy humans, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is secreted in a pulsatile fashion similar to that of leptin, reaching a peak in the early morning hours and nadir in late morning (175). Individuals with congenital leptin deficiency have a highly disorganized TSH secretion pattern, suggesting that leptin may regulate TSH pulsatility and circadian rhythm (175). Despite altered circadian rhythm of TSH, however, the thyroid phenotype varies among humans with congenital leptin deficiency, with most cases having normal thyroid function (144, 211).

Acute starvation-induced hypoleptinemia is also associated with abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in humans. We have shown that leptin administration in replacement doses prevents the fasting-induced changes in TSH pulsatility and increases free thyroxine concentration without affecting the fasting-induced fall in triiodothyronine concentration in healthy lean men with starvation-induced leptin deficiency (37). In another, intermediate study, in which we studied seven normal-weight women, replacement doses of leptin had no effect on fasting-induced changes in TSH pulsatility or thyroid hormone concentrations (40). We hypothesized that the fall in serum leptin concentration in these women did not reach the aforementioned threshold (40), beyond which we suggest that leptin replacement exerts a physiological effect. Taken together, these data indicate that decreasing leptin levels in states of energy deprivation may induce physiologically appropriate changes in the thyroid axis and through changes in thyroid possibly also on metabolism.

Hypothalamic-pituitary-growth hormone axis.

Both ob/ob and db/db mice have stunted growth curves and fragile growth plates (80, 81). Leptin enhances growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH)-induced GH secretion in rat anterior pituitary cells in vitro (216). Furthermore, it has been shown that leptin blunts the fasting-induced decrease in GH and increases longitudinal bone growth in normal rodents (81).

The GH axis in humans, however, is not affected by leptin in the same manner or to the same extent as it is in rodents. Children with congenital leptin deficiency have normal linear growth (66, 67), but children with the leptin receptor mutation can experience an early growth delay with subnormal concentrations of GH, IGF-I, and insulin'like growth factor-binding protein-3 (IGFBP3) (51). In healthy men, leptin replacement attenuates the starvation-induced fall in IGF-I but has no detectable short-term effect on circulating GH levels (37). In normal-weight women, in whom the starvation-induced fall in serum leptin is much less than that observed among men, leptin replacement does not prevent the reduction in IGF-I and IGFBP3 levels (40). Thus, it appears that in humans leptin may regulate not GH secretion per se but mainly the effect of GH (44) to regulate secretion of IGF-I and its binding proteins in the periphery. Mechanisms underlying these effects need to be studied in more detail in the future.

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is synthesized in the PVN, and leptin causes a dose-dependent stimulation of CRH release in vitro (58). ob/ob Mice exhibit increased adrenal stimulation by ACTH (22), and leptin administration blunts the stress-mediated increase in ACTH and cortisol in normal mice (102). From our analysis of leptin's pulse parameters, we have identified an inverse relationship between circulating leptin and ACTH in healthy men (149). However, studies in humans with mutations in the leptin or leptin receptor genes reveal that, despite abnormal leptin function, normal adrenal function is maintained (51, 66, 67, 69). Our earlier open-label studies of relative leptin deficiency in men with acute energy deprivation (i.e., starvation) and women with chronic energy deprivation (i.e., hypothalamic amenorrhea) (37, 273) showed no major effect of leptin replacement; but detailed studies were not performed. Similar results were reported in women with lipoatrophy and hypoleptinemia (202) studied in the context of an open-label study. The effects of leptin on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis were more pronounced and achieved statistical significance in a randomized, placebo-controlled study with metreleptin administration in physiological doses to leptin-deficient subjects (see below under Hypothalamic amenorrhea) (49). Thus, further investigation is needed to define whether the effects of leptin deficiency are counterbalanced by the activation of compensatory mechanisms or whether there is redundancy of the regulatory pathways.

Physiological Role of Leptin in the Regulation of Insulin Sensitivity

In the leptin-deficient ob/ob mouse, leptin injections led to significantly greater reductions in serum glucose levels in a dose-dependent manner compared with pair-fed ob/ob control animals even before any significant reduction in body weight (95, 213, 234), indicating that leptin may have direct effects in regulating insulin sensitivity independently of changes in body weight (130, 135, 142). Schwartz et al. (234) calculated that 42% of leptin's hypoglycemic action was independent of weight reduction. In contrast, the effects of leptin on whole body glucose metabolism in nonobese, nondiabetic animals remain inconsistent, but in general, short-term administration of leptin does not affect glucose metabolism (100, 227, 275). Similarly, the effects of leptin administration in animal models of diet-induced obesity, a model that provides important insights into understanding the effects of leptin on glucose metabolism in obese humans, also reveal largely null data (27, 283).

Mouse models of lipoatrophy, such as the AZIP/F-1 mouse, completely lack white adipose tissue and are therefore unable to produce adequate amounts of leptin. This results in a nearly 20-fold reduction in leptin concentration (24, 187). These mice also have a wide array of metabolic abnormalities, such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and fatty infiltration of the liver. Leptin has therefore been investigated as a regulator of insulin sensitivity (52). Transplantation of white adipose tissue in physiological quantities (86, 132), as well as exogenous leptin administration (246), improves insulin sensitivity in these mice. Other studies have shown that insulin sensitivity is fully restored with administration of the combination of leptin and adiponectin to lipoatrophic mice and only partially restored with either agent alone (281).

Interestingly, also, leptin treatment restores euglycemia and normalizes peripheral insulin sensitivity in animal models of type 1 diabetes, (48, 62, 77, 87, 104, 271). The mechanisms responsible for the effects of leptin in type 1 diabetic animals remain to be fully elucidated. Although leptin replacement normalizes food intake in animals with type 1 diabetes, pair-feeding studies indicate that decreased food intake cannot account for the restoration of normoglycemia in leptin-treated type 1 diabetic animals (104). Leptin may affect insulin sensitivity either through centrally mediated mechanisms or through direct peripheral effects of leptin in insulin-sensitive tissues. Thus, leptin may regulate glucose metabolism through other peripheral and/or central pathways. Peripherally, leptin treatment may activate signaling pathways that are similar albeit not identical with those activated by insulin and may alleviate the increase in plasma glucagon and growth hormone, which may contribute to the improvement in insulin sensitivity and mediate the restoration of euglycemia (62). Leptin infusion, probably acting through a central mechanism, inhibits hepatic glucose production, an effect potentially related to the downregulation of the expression of gluconeogenic genes in the liver such as G-6-Pase and PEPCK (87).

The presence of the long and short forms of the ObR in peripheral tissues supports the notion that leptin exerts direct physiological effects independently of signaling through the central nervous system (272). Several studies have reported that leptin increases glucose uptake in isolated soleus muscle in vivo and in animal models (13, 14, 33). These findings suggest that leptin exerts insulin-like effects on skeletal muscle. Leptin has also been shown to increase skeletal muscle glucose and fatty acid oxidation both in vitro and in vivo (185, 197, 250). These effects of leptin may be especially important because excessive deposition of lipids in skeletal muscle has been implicated in the development of insulin resistance (92). The mechanism by which leptin can directly affect glucose and fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscle remains to be elucidated. One proposed mechanism involves cross-talk between the leptin and insulin-signaling pathways, especially phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (129, 179). Another candidate for mediating the effect of leptin action on skeletal muscle is activation of 5-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Leptin directly stimulated fatty acid oxidation via AMPK-dependent pathways in isolated soleus muscle from FVB mice (185).

Leptin also directly affects glucose metabolism in the liver, which seems to be one of the primary tissues where leptin acts. Although leptin treatment did not elicit any changes in glucose production in hepatocytes under basal conditions, leptin significantly decreased the production of glucose in incubated hepatocytes in the presence of several gluconeogenic precursors (32). These effects appear to be mediated through PI3K-dependent activation of phosphodiesterase 3B (PDE3B) (288). Leptin also affects hepatic lipid metabolism via activation of PI3K rather than activation of AMPK (112). In human liver cells, leptin alone had no effects on the insulin-signaling pathway, but leptin pretreatment transiently enhanced insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and PI3K binding to IRS-1 (256). These findings are consistent with animal studies and suggest complex interactions between the leptin and insulin-signaling pathways on glucose metabolism in liver.

Leptin may alter the action of insulin in isolated adipocytes (214, 270) and may promote glucose and fatty acid oxidation and lipolysis (34). The observations from in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that leptin promotes energy dissipation and decreases lipid deposition in adipose tissue. Nevertheless, in human obesity and in some animal models of obesity, excessive lipid deposition in adipose tissues cannot be corrected despite the elevated circulating leptin levels. Apparently, there is a suppressive mechanism that impairs leptin action in adipose tissue. As expected, in studies using human preadipocytes and adipocytes from lean and obese subjects, leptin had no effect on basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake or on basal and isoproterenol-stimulated lipolysis (5). Recently, we performed detailed interventional and mechanistic signaling studies in human adipose tissue in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro (190). Leptin administration induced activation of STAT3 and AMPK signaling in human adipose tissue, and there was no difference between male and female and obese and lean subjects. Although there is convincing evidence indicating that leptin has favorable effects on adipose tissue metabolism, its effect in humans still needs to be fully elucidated.

It is also generally accepted that leptin significantly reduces insulin release from pancreatic β-cells under physiological conditions (4, 101, 119, 208). There are several mechanisms by which leptin may suppress insulin secretion by acting directly on the pancreas. Leptin affects the ATP-sensitive K+ channels through PI3K-dependent activation of PDE3B (101) and reduces glucose transport into β-cells (139). Leptin has also been shown to suppress preproinsulin mRNA and insulin promoter activity in vitro and in vivo (136, 237, 238). In these studies, leptin reduced preproinsulin mRNA expression only under conditions with stimulation by incretin hormones or high glucose concentrations. Recently, several studies demonstrated that leptin effectively inhibits glucagon secretion from pancreatic α-cells (180, 265). These findings suggest that leptin may modulate glucose homeostasis by inhibiting not only β-cell insulin release but also α-cell glucagon secretion. These observations also suggest that leptin represents a signaling molecule from adipose tissue to the endocrine pancreas that suppresses insulin secretion according to the needs dictated by body fat stores, and this connection establishes a classic endocrine feedback loop, the so-called “adipoinsular axis.”

The effects of leptin on glucose metabolism are much less pronounced in human skeletal muscle compared with results from animal studies. Leptin had no effects on either basal or insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in human skeletal muscle cells from normal subjects, obese subjects, and patients with type 2 diabetes (218). Also, leptin directly increases fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle from lean subjects but not from obese subjects (251). These findings provide more direct evidence of peripheral leptin resistance in obese humans.

Humans with congenital or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated lipoatrophy also have very low leptin levels (200, 210) and present with a profound lack of subcutaneous fat, insulin resistance, fatty infiltration of the liver, and increased cardiovascular risk (30, 93). As described below, leptin administration improves metabolic parameters in these patients (73, 263). Although leptin may directly affect pancreatic β-cell function (143), act as an insulin sensitizer, and improve metabolism in leptin-deficient subjects, it does not improve insulin sensitivity in obese human subjects (186) and does not activate intracellular signaling pathways and/or improve diabetes and glycemic control in obese humans with type 2 diabetes (191). In a human trial of leptin treatment in type 2 diabetic patients, glycemic control and body weight were not changed appreciably after leptin treatment even though serum leptin concentrations increased 150-fold compared with baseline in the high-dose group (103). Together, these observations imply that modulation of insulin sensitivity by leptin is also likely permissive, with diminished efficacy above a certain threshold (25).

In summary, activation of ObRb by leptin sets off a cascade of intracellular signal transduction pathways, including mainly the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/STAT3 pathway (79), but also the PI3K pathway (134), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways including extracellular signal-related kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK), and p38 (239, 242), and 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathways (1, 152, 185). Activation of individual pathways in the leptin-signaling network appears to be differentially regulated, and these pathways are also likely to be regulated by various other hormonal, neuronal, and metabolic signals that cross-talk with leptin. We have recently demonstrated, utilizing in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo signaling studies, that leptin administration activates the above-mentioned signaling pathways in a dose-response manner in several peripheral tissues, including fat, muscle, and peripheral mononuclear cells (190, 191). Moreover, we have shown that endoplasmic reticulum stress induces resistance to leptin signaling and that activation of signaling pathways is saturable at leptin levels of ∼50 ng/ml, which are levels seen in obese humans. These data can be interpreted as pointing to factors underlying leptin resistance in humans and need to replicated and extended.

Physiological Role of Leptin in the Regulation of Immune Function

Hypoleptinemic states are associated with increased risk of infection (24). A variety of immune cells express ObRb, and it is likely that leptin directly affects immune function (24, 155, 209). In ex vivo studies, leptin has been shown to enhance phagocytic activity in macrophages (160); promote production of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6, and interleukin-12 (154); and stimulate chemotaxis in polymorphonuclear cells (24, 29). In addition, we have shown that leptin promotes lymphocyte survival in vitro by suppressing Fas-mediated apoptosis (209). Overall, leptin promotes Th1 cell differentiation and cytokine production (182). An in vivo study showed that leptin administration improved the immune dysfunction of ob/ob mice and protected against immune dysfunction in acutely starved wild-type mice (110). Obese mice, in contrast, are tolerant to any effects of leptin administration (209).

The role of leptin in immune function also seems to be a permissive one in humans (16). Leptin-deficient children develop infections early in life, and many die because of these abnormalities (149). Leptin exogenously administered to children with congenital leptin deficiency greatly improves their immune function (67). In normal-weight women with a starvation-induced decrease in leptin to 2.8 ng/ml, leptin replacement had no major effect on fasting-induced changes on most immunophenotypes and did not affect in vitro proliferative and cytokine-producing capacity of T cells, suggesting that this degree of acute leptin deficiency only minimally disrupts immune function (40). Our group also showed that raising circulating leptin in lean men to levels between high physiological (as seen in obesity) and low pharmacological (as seen in extreme obesity) resulted in no significant increase in cytokine and inflammatory marker concentrations, including those known to be important in insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease, such as interferon-γ (IFNγ), interleukin-10, and TNF-α (36), a fact that, in part, may be due to saturable leptin signaling pathways in humans (190, 191). We found similar results in obese diabetic subjects after 4–16 weeks of leptin administration (36). Therefore, although leptin in replacement doses may restore the Th1/Th2 immune dysfunction in leptin-deficient animals and humans, leptin does not seem to be involved in the pathogenesis of an obesity-related proinflammatory state in humans. Thus, the role of leptin in the regulation of immune function seems to also be permissive in humans. It remains to be seen whether leptin administration can provide clinical benefits to subjects with negative energy balance such as cachexia or malnutrition, who are prone to and suffer from increased morbidity and mortality from infectious diseases (181).

Physiological Role of Leptin in the Regulation of Bone Metabolism

Early studies in mice suggested that leptin might decrease bone mass through mechanisms linking the central regulation of bone remodeling and energy metabolism (126). Initial radiographic and histological analyses revealed that ob/ob mice have a high bone mass phenotype, and intracerebroventricular infusion of leptin reduced bone mass in ob/ob and wild-type mice independently of weight loss (63). However, recent evidence suggests that leptin's action in murine bone varies among skeletal regions (50). ob/ob mice have significantly greater bone mineral density (BMD) and trabecular bone volume in the lumbar spine but lower BMD, trabecular bone volume, and cortical thickness in the femur than wild-type mice (50). In terms of whole body volume, ob/ob mice have lower bone mass than normal lean mice since the appendicular skeleton comprises 80% of total bone volume and consists primarily of cortical bone (50). There is a 20–25% decrease in total bone mass in the ob/ob and db/db mouse models, primarily at the site of cortical bone (98, 156, 252). Peripheral leptin administration has been shown to increase bone mineral content and density in ob/ob mice (98, 252).

Leptin affects bone metabolism through both central and peripheral pathways. In mice, leptin appears to regulate the formation of cortical bone via sympathetic activation (97). ob/ob mice have diminished sympathetic tone (257), and leptin action in the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) can increase sympathetic activity (97). Furthermore, compared with wild-type mice, β1- and β2-adrenergic receptor knockout mice exhibit decreased cortical thickness and femoral mass (97) and low leptin levels (176). Data from rodent studies also suggest that leptin may mediate cortical bone formation by regulating the expression of several hypothalamic neuropeptides. One study found that mice lacking the NPY receptor Y2 have femurs with increased cortical bone mass and density (10), indicating that NPY inhibits cortical bone formation (97). However, leptin injection into the PVN has been shown to increase expression of neuromedin U (279), which may decrease both cortical and trabecular bone mass (231). Moreover, Yadav et al. (280) have shown that brainstem-derived serotonin binds to Htr2c receptors on VMH neurons, favoring bone mass accrual, and that leptin inhibits this effect by reducing serotonin synthesis and firing of serotonergic neurons. Thus, it appears that leptin affects the expression of many neuropeptides that positively or negatively affect bone metabolism.

Peripherally administered leptin increases bone mass through interactions with bone marrow stromal cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts. In stromal cells, leptin increases expression of osteogenic genes and directs them to the osteogenic instead of the adipogenic pathway (98, 99, 259). Furthermore, leptin increases osteoblast proliferation, de novo collagen synthesis, and mineralization in in vitro and in vivo mouse studies (89). Finally, leptin decreases osteoclastogenesis by stimulating stromal cells to increase osteoprotegerin expression and by decreasing receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK) ligand (107).

It remains unclear whether data from rodent studies also apply to humans. For example, we have shown that, in contrast to findings in mice, leptin does not regulate short-term fasting-induced autonomic changes and/or catecholamine levels (41). Indeed, the contrasting effects of leptin in the axial and appendicular skeleton of ob/ob mice do not appear to manifest in humans, as individuals with leptin deficiency have decreased bone mass and density throughout the skeleton (97). Using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, we assessed bone mineral content (BMC) and BMD in normal-weight children and adolescents (222). We found no relationship between leptin and BMD or BMC for either total body or body regions, after adjusting for age, fat mass, bone-free fat mass, and serum IGF-I and estradiol concentrations (222). It has also been observed that leptin levels do not correlate with BMD or BMC in healthy postmenopausal women after adjustment for body composition (124). These data seem to indicate that leptin's effect on bone metabolism reflects that of fat mass and may be mediated through changes in estradiol and IGF-I or other hormone levels. This is consistent with our recent findings that in leptin (and thus estradiol and IGF-I) -deficient women with hypothalamic amenorrhea there might be a weak association between circulating leptin levels and BMD/BMC (7).

Hypotheses raised by these animal and observational studies in humans on the effects of leptin on bone metabolism in humans, including bone macro- and microarchitecture, as well as the underlying signaling pathways, have just started to be studied in the context of interventional studies in humans and merit further investigation. The observations to date collectively suggest that leptin's effect on bone metabolism may also be permissive and that leptin may have a distinct therapeutic role in treating the low bone density of several disease states associated with negative energy balance (see below, Hypothalamic Amenorrhea).

LEPTIN DEFICIENCY AND LEPTIN THERAPY IN HUMAN DISEASE

Leptin replacement has been investigated for its physiological role in several conditions characterized by leptin deficiency. The main conditions that have been studied are congenital leptin deficiency, lipodystrophy, hypothalamic amenorrhea, and weight loss (39, 128).

Congenital Leptin Deficiency

Congenital leptin deficiency is a rare autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the leptin gene. In addition to marked obesity mainly due to hyperphagia, congenital leptin deficiency is associated with inadequate secretion of GnRH, manifesting in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and, in most cases, failure to reach puberty, including absence of growth spurt, secondary sex characteristics, and menarche (253).

Leptin replacement reverses several of the changes seen with congenital leptin deficiency. There is usually marked weight loss. For example, in three adult patients treated with leptin, the average BMI dropped from 51.2 to 29.5 kg/m2 (212). Leptin replacement can also improve the hyperinsulinemia and dyslipidemia seen in these individuals (67, 88). In terms of neuroendocrine function, leptin replacement permits the appropriate progression through puberty (66, 67, 148). In an uncontrolled study of leptin replacement in three children with congenital leptin deficiency (67), a gradual increase in gonadotropins and estradiol and normalization of pulsatile secretion of LH and FSH were observed after 24 mo of leptin therapy in one child who was of appropriate pubertal age (67). In a similar study in adults with congenital leptin deficiency, it was observed that leptin replacement in men increased testosterone levels, and facial, pubic, and axillary hair, promoted penile and testicular growth, and permitted normal ejaculatory patterns (148).

Less dramatic changes were seen in the other neuroendocrine axes. A small, uncontrolled interventional study reported no major change in TSH after leptin replacement in children with congenital leptin deficiency, although participants did exhibit increased levels of triiodothyronine and thyroxine (67). Another uncontrolled study of three adults and one boy with congenital leptin deficiency observed normal thyroid function and no changes with leptin replacement (144, 211). Despite the fact that patients with congenital leptin deficiency have age- and sex-appropriate BMC and BMD, leptin treatment increases their skeletal maturation (67).

Finally, in terms of immune function, individuals with congenital leptin deficiency have a greater incidence of infection than the general population (205) due to decreased proliferation and function of CD4+ T cells, which normalizes with exogenous leptin administration (67). Leptin is currently available for life-long treatment of subjects with congenital leptin deficiency through an Amylin-sponsored compassionate leptin access program (73, 168).

Lipodystrophy

Lipodystrophy and lipoatrophy are disorders of adipose tissue characterized by loss of subcutaneous adipose tissue, usually associated with an increase in visceral adipose tissue. Congenital lipoatrophy is a rare autosomal recessive condition often associated with consanguineous marriage (201, 210). Leptin replacement has been studied in approximately 100 subjects with this condition in the context of small, uncontrolled interventional studies. These showed that leptin replacement therapy dramatically improves dyslipidemia and insulin sensitivity in these individuals and reduces glycosylated hemoglobin and hepatic gluconeogenesis and intrahepatic fat content (121, 122, 203, 215). Hb A1c is reduced by ∼3% in these subjects who are not responsive to other antihyperglycemic medications and/or high doses of insulin. Furthermore, leptin also normalizes testosterone levels and restores menstrual function in women with lipoatrophy. An open-label study in individuals with congenital lipoatrophy found that leptin replacement increased LH response to GnRH in women and increased testosterone levels in men (198). In addition, all eight women who had been amenorrheic prior to treatment resumed normal menses (198). Studies in both rodents and humans have shown that the improvement in glucose metabolism may be a direct effect of leptin replacement or an indirect effect due to reduction in ectopic fat, i.e., fat deposited in tissues other than adipose tissue such as the liver and muscle (24). Indeed, we have recently shown that leptin administration activated, in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo, intracellular signaling pathways that overlap with those activated by insulin (190, 191). Thus, in addition to its lipolytic effect, which may indirectly improve metabolism and insulin resistance, leptin may also have direct effects in metabolically important tissues by directly activating signaling pathways that overlap, but are not completely identical, with signaling pathways activated by insulin (190, 191).

HIV-associated lipoatrophy is a much more prevalent condition, affecting an estimated 15–36% of HIV-infected patients (120) and is closely linked with insulin resistance and dysregulation of peripheral adipose tissue metabolism (159, 235, 262). In our initial randomized, placebo-controlled, interventional study, we found that leptin in physiological doses improves insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and truncal fat mass in these patients (23, 141). These results were confirmed by a longer independent study of open-label leptin treatment for 6 mo, which further demonstrated that the improvement in whole body insulin resistance in lipoatrophic patients is predominantly due to improved hepatic (i.e., suppression of endogenous glucose production) but not skeletal muscle (i.e., stimulation of glucose uptake) insulin sensitivity (195). Recently, we also demonstrated that leptin treatment in HIV lipoatrophic patients treated with pioglitazone also improves postprandial glucose metabolism (158). The favorable effects of leptin on insulin sensitivity in these patients could in part be due to potentiating the effect of pioglitazone (a thiazolidinedione) (84) on adiponectin secretion and plasma concentration (158), because leptin administration alone does not alter adiponectin levels (83, 141).

Studies performed to date indicate that leptin's ability to improve metabolic control, lipid levels, and truncal fat mass is comparable to or better than that induced by insulin sensitizers (169). Leptin may have beneficial effects through its lipolytic effect and/or by altering levels of other peripherally secreted molecules important in regulating insulin resistance and metabolism (6, 43, 82, 96, 125, 232, 254, 276). Nevertheless, leptin improves insulin resistance not only by decreasing body weight and fat mass, especially ectopic fat or intra-abdominal fat (192, 195), but also by activating insulin-sensitive tissues, including adipose tissue and liver (134). Leptin activates signaling pathways that overlap with those of insulin, including STAT3, MAPK, and PI3K in mice (134). As mentioned above, we have confirmed these findings and have extended them by performing in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro studies in humans, revealing that leptin activated signaling pathways overlapping with those activated by insulin (190). Further study of these signaling pathways and possibly the identification of loci of leptin resistance may be of therapeutic significance, since it may identify areas where future intervention may improve leptin tolerance or resistance and thus help treat insulin resistance in obese, hyperleptinemic subjects who are currently tolerant of or resistant to the insulin-sensitizing effect of leptin (255).

Hypothalamic Amenorrhea

Hypothalamic amenorrhea is a common cause of absent menstrual periods and infertility. It is typically seen in women who are in a state of relative energy deficiency, such as those who exercise vigorously or have a low body fat mass such as in anorexia nervosa. These women are hypoleptinemic (19, 127).

Leptin replacement may be a promising treatment for infertility in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea (18, 273). In our proof-of-concept trial of leptin replacement, we found that leptin can normalize LH concentrations and pulse frequency within weeks of treatment and can restore ovulatory function after only months of treatment (273). Since many participants were amenorrheic for years, these results are remarkable and were independent of changes in body weight and fat mass (273). We have recently confirmed these findings in a larger double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study of leptin replacement for 9 mo (49). Together, our results indicate that leptin therapy resulted in resumption of menses with irregular but sustained menstrual cycles in ∼70% of the subjects. Additionally, ∼60% of the subjects who menstruated also ovulated. Menstruation appeared at various stages of leptin therapy, ranging from 4 to 8 wk after initiation of treatment in the open-label 10-wk study and from 4 to 32 wk in the randomized, placebo-controlled 9-mo study (49, 273). Importantly, increasing the administered dose of leptin in some women who did not menstruate with the lower leptin dose turned out to be a feasible way to resolve amenorrhea (49).

Leptin replacement in these women may also affect other neuroendocrine axes (17). The effects on thyroid hormones were modest. In women with hypothalamic amenorrhea and average baseline leptin concentration of 3.4 ng/ml, leptin treatment significantly increased triiodothyronine and free thyroxine levels but did not affect TSH levels (273). Lesser effects were observed in another group of such women with baseline leptin concentration of 4.6 ng/ml, in whom leptin replacement mildly increased free triiodothyronine and did not affect free thyroxine or TSH concentrations (49).

We also observed beneficial changes in the growth hormone axis with leptin replacement. There was a significant increase in IGF-I and IGFBP3 levels after leptin administration for 10 wk (273), whereas 9 mo of leptin replacement only marginally affected IGF-I and IGFBP3 concentrations but led to increased ratio of IGF-I to IGFBP3 (49), indicating that leptin augments the availability of free IGF-I. We found no change in the adrenal axis in our earlier open-label study of leptin replacement (37, 273), although there was a small but statistically significant decrease in cortisol concentration after leptin replacement in our recent randomized, placebo-controlled trial (49). These data in leptin-deficient women are in contrast to data demonstrating a lack of an effect of leptin administration to improve bone metabolism in obese and thus presumably leptin-tolerant or -resistant women (55, 90). Finally, leptin replacement in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea and chronic relative leptin deficiency leads to greater activation of the TNF-α system (42), but the full effects on the immune system remain to be elucidated.

In women with hypothalamic amenorrhea, we also reported a significant increase in bone formation markers (osteocalcin and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase) after leptin administration for 10 wk but no change in total body and regional BMC and BMD, which was not surprising given the short duration of the study (273). Moreover, we were unable to determine whether this increase in bone formation markers is a direct effect of leptin or an indirect effect mediated by restoration of estradiol and/or IGF-I levels. In a recent randomized, placebo-controlled study (247), we confirmed the leptin-induced increase in markers of bone formation after 9 mo of leptin treatment in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. Importantly, we documented a significant increase in lumbar spine BMC and BMD by 4–6% in six of those women who continued beyond the first 9 mo of double-blinded treatment to an open-label leptin replacement study for an additional year (247). These data indicate that long-term (2 yr) leptin replacement has a favorable effect on bone (predominantly trabecular bone), although we cannot rule out the possibility that changes would also manifest at the other sites examined (hip, radius) with more prolonged treatment. Interestingly, after 2 yr of leptin replacement, we observed a decrease in markers of bone resorption such as CTX (cross-linked COOH-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen), as opposed to the increase in markers of bone formation earlier into treatment (49, 273).

Weight Loss

As described above, leptin levels are higher in most obese subjects (173) and reduced in the setting of acute starvation. The reduction of fat mass occurring during weight loss results in decreased leptin concentrations (189, 172). Emerging evidence suggests that leptin may play a more important role in weight loss maintenance rather than weight loss per se. As leptin levels fall, energy expenditure, sympathetic nervous system tone, and thyroid hormones decrease to collectively drive patients to regain weight (223).

In a study of lean and obese subjects with relative hypoleptinemia (10–60 ng/ml) due to moderate weight loss, leptin replacement to increase serum leptin concentration to pre-weight loss levels over an average period of 8 wk resulted in an increase in circulating concentrations of triiodothyronine and thyroxine but no change in TSH, which was reduced compared with baseline (223). This effect of leptin may be especially important because the mechanisms through which body weight returns to baseline are thought to involve a compensatory decrease in energy expenditure (146) due to decreasing thyroid hormone levels resulting in increased skeletal muscle work efficiency (223, 226). However, other studies in overweight and obese subjects during severe (113) and mild (244) caloric restriction found no effects of leptin administration in pharmacological doses on circulating thyroid hormone levels. The lack of a significant change in TSH levels in most studies may be due to the pulsatile nature of TSH, requiring careful timing of sampling. It has been proposed that leptin may directly stimulate thyroxine release from the thyroid gland and/or increase the bioactivity of TSH (223).

On the other hand, leptin administration does not have major effects on other physiological processes that have been studied. Pharmacological leptin administration in overweight and obese subjects during weight loss induced by severe (113) and mild (244) hypocaloric diet does not affect IGF-I and IGFBP3 concentrations or their ratio. Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that leptin replacement in normal-weight, overweight, and obese subjects after moderate weight loss (in whom leptin concentration dropped relative to baseline but did not reach clearly hypoleptinemic levels) failed to affect circulating markers of bone formation and resorption (55). In addition, functional magnetic resonance imaging data also suggest that leptin treatment can prevent the changes in brain activity involved in the regulatory, emotional, and cognitive control of food intake following weight loss (225).

The role of leptin in weight loss maintenance is an area of active investigation, and there are currently several clinical trials under way that aim at further evaluating the role of leptin treatment in weight loss maintenance (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00265980, NCT01155180, NCT00073242), the results of which are eagerly awaited. It is expected, however, that leptin alone will not be sufficient to overcome the problem of leptin tolerance or resistance associated with obesity and that the development of novel medication with the ability to boost leptin's efficiency will eventually be needed.

LEPTIN EXCESS DUE TO LEPTIN RESISTANCE OR TOLERANCE IN HUMAN DISEASE

In contrast to obese subjects with congenital leptin deficiency, garden-variety obese individuals have greater leptin concentrations than lean individuals and are resistant or tolerant to the effects of leptin (57, 191). Initial attempts to utilize leptin as a monotherapy for obesity included using supraphysiological doses of leptin (75, 103, 147); however, data from these trials revealed modest, if any, weight loss and with significant variability among the participants. In a small, proof-of-concept, phase II clinical trial, Heymsfield et al. (103) administered leptin in escalating doses to obese participants for up to 24 wk. Although a dose-dependent response was noted, participants exhibited only modest weight loss despite supraphysiological doses of leptin (103). With the highest dose of leptin at 0.30 mg·kg−1·day−1, obese participants who completed the study lost a mean of 7.1 kg; however, when participants who withdrew from the study were included in the analysis, there was only a mean weight loss of 3.3 kg (103). Furthermore, there was significant variability among the participants in the response to leptin treatment (103). Hukshorn et al. (114) have also tried pegylated leptin, which has a much longer half-life. In their randomized, double-blinded trial in obese men receiving weekly injections of pegylated leptin for 12 wk, there were no significant differences in weight loss or percent body fat (114). Generally, only at supraphysiological doses does leptin induce some degree of weight loss in obese subjects, and even then the effect is very mild and likely clinically insignificant (103, 113). In accordance with the concept of leptin resistance or tolerance in obesity, the effects of leptin on weight loss and other physiological parameters appear to be most pronounced during states of relative leptin deficiency, e.g., fasting and hypothalamic amenorrhea or lipoatrophy (26, 141, 195).

Leptin resistance or tolerance was first thought to be due to mutations of the leptin receptor (51) and other rare monogenic obesity syndromes (68). However, most instances appear to be multifactorial; only a few cases of human obesity are due to monogenic syndromes (69). Although it was determined that the exact defect in the leptin receptor present in db/db mice is not present in obese humans, several genetic variants are associated with hyperleptinemia (56), including the Lys109Arg or Gln223Arg mutation in the leptin receptor (LEPR) gene (138), Mutations of other genes downstream of leptin, including POMC and the melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R), also result in an obese phenotype with associated neuroendocrine dysfunction (70). Additional variants include the 241G/A variant (the Val18 missense mutation) of the melanocortin 3 receptor (MC3R) (284) and the two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs17817449 and rs1421085 found in the fatso/fat mass- and obesity-associated gene (FTO) (267). Other genetic variants that may predispose patients to develop leptin resistance or tolerance remain to be further investigated.

Leptin transport across the blood-brain barrier is impaired in obesity. This is partially due to saturation of the transporter as a result of hyperleptinemia and a subsequent decrease in transport activity (11, 28, 269). Moreover, different brain regions may saturate at different concentrations. Banks et al. (12) used a brain perfusion method to deliver leptin at certain concentrations in mice. By use of a concentration seen in hypoleptinemic lean humans (1 ng/ml), the hypothalamus contained a higher concentration of leptin than any other brain region. At the concentration representing obese humans (30 ng/ml), the hypothalamus contained less leptin than other regions (12). The selective activation of brain regions at certain concentrations implies that there can be different thresholds for different actions of leptin (12). In addition, the soluble leptin receptor isoform ObRe antagonizes leptin transport by inhibiting surface binding and endocytosis of leptin (264).

Leptin signaling is subject to negative feedback regulation, which may be more pronounced in the obese state and associated hyperleptinemia (204). The expression of SOCS3, a major inhibitor of leptin signaling, is induced by the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, and SOCS3 acts to inhibit the phosphorylation and activation of JAK2 and ObRb tyrosine residue Tyr985 (199). Leptin administration leads to increased STAT3 expression and greater weight loss in SOCS3 knockout mice (109, 193). Another negative regulator of STAT3-mediated gene induction is SHP2, which is also activated by leptin (31). Finally, protein-tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP1B) is another molecule that may inhibit leptin signaling by dephosphorylating JAK2. PTP1B knockout mice have increased leptin sensitivity and reduced fatness (204). These feedback mechanisms may explain why excessive leptin can actually result in the same disturbances as leptin deficiency (e.g., insulin resistance and infertility) (24). We (190, 191) have recently confirmed that similar signaling pathways are activated by leptin in humans, but it remains currently unknown whether leptin signaling inhibition does exist in humans in vivo or whether leptin signaling is simply saturable at relatively higher leptin levels. This remains an area of active investigation in our laboratory.

Endoplasmic reticulum stress has recently been shown to play a role in the development of leptin resistance. Obese diabetic animals and humans have been shown to have higher levels of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the liver, adipose tissue, and pancreatic β-cells (21, 177, 207, 241). Studies in obese mice have shown that increased endoplasmic reticulum stress inhibits leptin receptor signaling in the hypothalamus, and chemical chaperones that decrease endoplasmic reticulum stress have been shown to increase leptin sensitivity (206). Furthermore, induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress via intracerebroventricular administration of thapsigargin results in increased food intake and body weight (277). We have recently performed a series of in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro signaling studies in lean and obese nondiabetic and type 2 diabetic men and women and found that endoplasmic reticulum stress attenuates or completely inhibits leptin signaling (190, 191). Thus, the negative effect of endoplasmic reticulum stress on leptin sensitivity may also contribute to insulin resistance.

Targeting these mechanisms of leptin resistance will be important in the treatment for obesity and has led to development of leptin sensitizers, including the chemical chaperones mentioned above. Roth et al. (228) have also proposed that amylin may act synergistically with leptin to induce fat-specific weight loss, and the amylin analog pramlintide has been tried in conjunction with leptin in clinical trials for weight loss with modest effects (219). In a recent phase II clinical trial, the combination of pramlintide and human recombinant leptin in obese and overweight human subjects produced significantly more weight loss than either treatment alone (219). The results, however, appeared to be additive rather than synergistic, implying that amylin may have independent effects on weight loss but does not likely improve sensitivity to leptin. We have recently shown that leptin administration does not influence circulating amylin levels (116) and subsequently we have performed ex vivo and in vitro signaling studies that are consistent with these clinical observations (143, 292). We demonstrated that leptin and amylin alone and in combination activate STAT3, AMP-activated protein kinase, Akt, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathways in human adipose tissue ex vivo and human primary adipocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro; all phosphorylation events were saturable at leptin and amylin concentrations of ∼50 and 20 ng/ml, respectively (190). These data indicate that leptin and amylin activate overlapping intracellular signaling pathways in humans and have additive, but not synergistic, effects. Moreover, the saturable nature of leptin signaling may underly the development of tolerance to leptin's effects at levels above ∼50 ng/ml (190, 191). Results of studies on combination treatments or the development of leptin “sensitizers” that would enhance leptin's efficacy are awaited with great interest.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Observational and interventional studies in animals and humans have shown that leptin contributes to the regulation of energy homeostasis, neuroendocrine function, metabolism, immune function, and bone metabolism (78). Both complete (e.g., congenital leptin deficiency) and partial (e.g., hypothalamic amenorrhea, lipoatrophy) leptin deficiency states present with dysfunction in these systems that can be reversed, in part or in whole, with leptin treatment. Although the vast majority of obese individuals are hyperleptinemic and resistant or tolerant to exogenous leptin, further research is needed to elucidate whether leptin sensitizers will be useful and if leptin has a role in weight loss maintenance. For the time being, available data suggest that leptin deficiency is not so different from other hormone deficiency states and can thus be treated accordingly (60). Thus, it is anticipated that large double-blinded phase III clinical trials in humans will prove in the not so distant future the role of leptin administration in replacement doses to correct abnormalities in leptin-deficient disease states such as lipodystrophy or hypothalamic amenorrhea. By contrast, states of leptin excess, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, appear to be states associated with leptin tolerance, in which leptin alone is not expected to have appreciable clinical significance.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are reported by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Mantzoros group is supported by Grants DK-58785, DK-079929, and DK-081913 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and a VA Merit Review Award.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahima RS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Obesity (Silver Spring) 14, Suppl 5: 242S–249S, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahima RS, Dushay J, Flier SN, Prabakaran D, Flier JS. Leptin accelerates the onset of puberty in normal female mice. J Clin Invest 99: 391–395, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D, Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature 382: 250–252, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahren B, Havel PJ. Leptin inhibits insulin secretion induced by cellular cAMP in a pancreatic B cell line (INS-1 cells). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R959–R966, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aprath-Husmann I, Rohrig K, Gottschling-Zeller H, Skurk T, Scriba D, Birgel M, Hauner H. Effects of leptin on the differentiation and metabolism of human adipocytes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25: 1465–1470, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aronis KN, Diakopoulos KN, Fiorenza CG, Chamberland JP, Mantzoros CS. Leptin administered in physiological or pharmacological doses does not regulate circulating angiogenesis factors in humans. Diabetologia 54: 2358–2367, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aronis KN, Kilim H, Chamberland JP, Breggia A, Rosen C, Mantzoros CS. Preadipocyte factor-1 levels are higher in women with Hypothalamic Amenorrhea and are associated with bone mineral content and bone mineral density through a mechanism independent of leptin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab July 27 [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 21795455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Asimakopoulos B, Milousis A, Gioka T, Kabouromiti G, Gianisslis G, Troussa A, Simopoulou M, Katergari S, Tripsianis G, Nikolettos N. Serum pattern of circulating adipokines throughout the physiological menstrual cycle. Endocr J 56: 425–433, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Audi L, Mantzoros CS, Vidal-Puig A, Vargas D, Gussinye M, Carrascosa A. Leptin in relation to resumption of menses in women with anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry 3: 544–547, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baldock PA, Allison S, McDonald MM, Sainsbury A, Enriquez RF, Little DG, Eisman JA, Gardiner EM, Herzog H. Hypothalamic regulation of cortical bone mass: opposing activity of Y2 receptor and leptin pathways. J Bone Miner Res 21: 1600–1607, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Banks WA. Leptin transport across the blood-brain barrier: implications for the cause and treatment of obesity. Curr Pharm Des 7: 125–133, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Banks WA, Clever CM, Farrell CL. Partial saturation and regional variation in the blood-to-brain transport of leptin in normal-weight mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 278: E1158–E1165, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bates SH, Gardiner JV, Jones RB, Bloom SR, Bailey CJ. Acute stimulation of glucose uptake by leptin in l6 muscle cells. Horm Metab Res 34: 111–115, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berti L, Kellerer M, Capp E, Haring HU. Leptin stimulates glucose transport and glycogen synthesis in C2C12 myotubes: evidence for a PI3-kinase mediated effect. Diabetologia 40: 606–609, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bjorbaek C, Elmquist JK, Michl P, Ahima RS, van Bueren A, McCall AL, Flier JS. Expression of leptin receptor isoforms in rat brain microvessels. Endocrinology 139: 3485–3491, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bluher S, Mantzoros CS. Leptin in humans: lessons from translational research. Am J Clin Nutr 89: 991S–997S, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bluher S, Mantzoros CS. Leptin in reproduction. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 14: 458–464, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bluher S, Mantzoros CS. The role of leptin in regulating neuroendocrine function in humans. J Nutr 134: 2469S–2474S, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bluher S, Shah S, Mantzoros CS. Leptin deficiency: clinical implications and opportunities for therapeutic interventions. J Investig Med 57: 784–788, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boden G, Chen X, Mozzoli M, Ryan I. Effect of fasting on serum leptin in normal human subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 3419–3423, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boden G, Duan X, Homko C, Molina EJ, Song W, Perez O, Cheung P, Merali S. Increase in endoplasmic reticulum stress-related proteins and genes in adipose tissue of obese, insulin-resistant individuals. Diabetes 57: 2438–2444, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bray GA, York DA. Hypothalamic and genetic obesity in experimental animals: an autonomic and endocrine hypothesis. Physiol Rev 59: 719–809, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brennan AM, Lee JH, Tsiodras S, Chan JL, Doweiko J, Chimienti SN, Wadhwa SG, Karchmer AW, Mantzoros CS. r-metHuLeptin improves highly active antiretroviral therapy-induced lipoatrophy and the metabolic syndrome, but not through altering circulating IGF and IGF-binding protein levels: observational and interventional studies in humans. Eur J Endocrinol 160: 173–176, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brennan AM, Mantzoros CS. Drug Insight: the role of leptin in human physiology and pathophysiology—emerging clinical applications. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2: 318–327, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brennan AM, Mantzoros CS. Leptin and adiponectin: their role in diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 7: 1–2, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brinkoetter M, Magkos F, Vamvini M, Mantzoros CS. Leptin treatment reduces body fat but does not affect lean body mass or the myostatin-follistatin-activin axis in lean hypoleptinemic women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301: E99–E104, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buettner R, Newgard CB, Rhodes CJ, O'Doherty RM. Correction of diet-induced hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and skeletal muscle insulin resistance by moderate hyperleptinemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 278: E563–E569, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burguera B, Couce ME, Curran GL, Jensen MD, Lloyd RV, Cleary MP, Poduslo JF. Obesity is associated with a decreased leptin transport across the blood-brain barrier in rats. Diabetes 49: 1219–1223, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caldefie-Chezet F, Poulin A, Vasson MP. Leptin regulates functional capacities of polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Free Radic Res 37: 809–814, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Capeau J, Magre J, Lascols O, Caron M, Bereziat V, Vigouroux C, Bastard JP. Diseases of adipose tissue: genetic and acquired lipodystrophies. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 1073–1077, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carpenter LR, Farruggella TJ, Symes A, Karow ML, Yancopoulos GD, Stahl N. Enhancing leptin response by preventing SH2-containing phosphatase 2 interaction with Ob receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 6061–6066, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ceddia RB, Lopes G, Souza HM, Borba-Murad GR, William WN, Jr, Bazotte RB, Curi R. Acute effects of leptin on glucose metabolism of in situ rat perfused livers and isolated hepatocytes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 23: 1207–1212, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ceddia RB, William WN, Jr, Curi R. Comparing effects of leptin and insulin on glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle: evidence for an effect of leptin on glucose uptake and decarboxylation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 23: 75–82, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ceddia RB, William WN, Jr, Lima FB, Curi R. Leptin inhibits insulin-stimulated incorporation of glucose into lipids and stimulates glucose decarboxylation in isolated rat adipocytes. J Endocrinol 158: R7–R9, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chan JL, Bluher S, Yiannakouris N, Suchard MA, Kratzsch J, Mantzoros CS. Regulation of circulating soluble leptin receptor levels by gender, adiposity, sex steroids, and leptin: observational and interventional studies in humans. Diabetes 51: 2105–2112, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chan JL, Bullen J, Stoyneva V, Depaoli AM, Addy C, Mantzoros CS. Recombinant methionyl human leptin administration to achieve high physiologic or pharmacologic leptin levels does not alter circulating inflammatory marker levels in humans with leptin sufficiency or excess. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 1618–1624, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chan JL, Heist K, DePaoli AM, Veldhuis JD, Mantzoros CS. The role of falling leptin levels in the neuroendocrine and metabolic adaptation to short-term starvation in healthy men. J Clin Invest 111: 1409–1421, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan JL, Mantzoros CS. Leptin and the hypothalamic-pituitary regulation of the gonadotropin-gonadal axis. Pituitary 4: 87–92, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chan JL, Mantzoros CS. Role of leptin in energy-deprivation states: normal human physiology and clinical implications for hypothalamic amenorrhoea and anorexia nervosa. Lancet 366: 74–85, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chan JL, Matarese G, Shetty GK, Raciti P, Kelesidis I, Aufiero D, De Rosa V, Perna F, Fontana S, Mantzoros CS. Differential regulation of metabolic, neuroendocrine, and immune function by leptin in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 8481–8486, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chan JL, Mietus JE, Raciti PM, Goldberger AL, Mantzoros CS. Short-term fasting-induced autonomic activation and changes in catecholamine levels are not mediated by changes in leptin levels in healthy humans. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 66: 49–57, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chan JL, Moschos SJ, Bullen J, Heist K, Li X, Kim YB, Kahn BB, Mantzoros CS. Recombinant methionyl human leptin administration activates signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vivo and regulates soluble tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor levels in humans with relative leptin deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 1625–1631, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chan JL, Stoyneva V, Kelesidis T, Raciti P, Mantzoros CS. Peptide YY levels are decreased by fasting and elevated following caloric intake but are not regulated by leptin. Diabetologia 49: 169–173, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chan JL, Williams CJ, Raciti P, Blakeman J, Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Johnson ML, Thorner MO, Mantzoros CS. Leptin does not mediate short-term fasting-induced changes in growth hormone pulsatility but increases IGF-I in leptin deficiency states. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 2819–2827, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chan JL, Wong SL, Mantzoros CS. Pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous recombinant methionyl human leptin administration in healthy subjects in the fed and fasting states: regulation by gender and adiposity. Clin Pharmacokinet 47: 753–764, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chan JL, Wong SL, Orlova C, Raciti P, Mantzoros CS. Pharmacokinetics of recombinant methionyl human leptin after subcutaneous administration: variation of concentration-dependent parameters according to assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 2307–2311, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chehab FF, Lim ME, Lu R. Correction of the sterility defect in homozygous obese female mice by treatment with the human recombinant leptin. Nat Genet 12: 318–320, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chinookoswong N, Wang JL, Shi ZQ. Leptin restores euglycemia and normalizes glucose turnover in insulin-deficient diabetes in the rat. Diabetes 48: 1487–1492, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chou SH, Chamberland JP, Liu X, Matarese G, Gao C, Stefanakis R, Brinkoetter MT, Gong H, Arampatzi K, Mantzoros CS. Leptin is an effective treatment for hypothalamic amenorrhea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 6585–6590, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]