Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRs) are endogenous small RNA molecules that suppress gene expression by binding to complementary sequences in the 3′ untranslated regions of their target genes. miRs have been implicated in many diseases, including heart failure, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and cancers. Nitric oxide (NO) and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) are potent vasorelaxants whose actions are mediated through receptor guanylyl cyclases and cGMP-dependent protein kinase. The present study examines miRs in signaling by ANP and NO in vascular smooth muscle cells. miR microarray analysis was performed on human vascular smooth muscle cells (HVSMC) treated with ANP (10 nM, 4 h) and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) (100 μM, 4 h), a NO donor. Twenty-two shared miRs were upregulated, and 21 shared miRs were downregulated, by both ANP and SNAP (P < 0.05). Expression levels of four miRs (miRs-21, -26b, -98, and -1826), which had the greatest change in expression, as determined by microarray analysis, were confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR. Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPS, a cGMP-dependent protein kinase-specific inhibitor, blocked the regulation of these miRs by ANP and SNAP. 8-bromo-cGMP mimicked the effect of ANP and SNAP on their expression. miR-21 was shown to inhibit HVSMC contraction in collagen gel lattice contraction assays. We also identified by computational algorithms and confirmed by Western blot analysis new intracellular targets of miR-21, i.e., cofilin-2 and myosin phosphatase and Rho interacting protein. Transfection with pre-miR-21 contracted cells and ANP and SNAP blocked miR-21-induced HVSMC contraction. Transfection with anti-miR-21 inhibitor reduced contractility of HVSMC (P < 0.05). The present results implicate miRs in NO and ANP signaling in general and miR-21 in particular in cGMP signaling and vascular smooth muscle cell relaxation.

Keywords: guanosine 3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphate miR-21

micrornas (mirs) have emerged as a novel class of endogenous small RNA molecules that negatively regulate ∼30% of genes in the cell by annealing with complementary sequences in the 3′ untranslated regions of their target mRNAs. More than 1,000 miRs have been identified in the human genome. A single miR can regulate hundreds of functional targets, and, similarly, a single mRNA can be targeted by multiple miRs in a cell (2). Recent evidence suggests roles for miRs in diverse processes including cell differentiation and proliferation (3, 19, 22). Aberrant expression of miRs has been linked to developmental abnormalities and pathologies, including cardiac hypertrophy, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and cancers (8, 24, 33, 56, 68, 69).

The potential role of miRs in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) biology and blood pressure is just beginning to be appreciated. Both miR-143 and miR-145 control phenotype switching of smooth muscle cells by modulating actin dynamics. Mice lacking miR-143 and miR-145 develop significant reduction in blood pressure due to reduced vascular tone (68). Myocardin-induced miR-1 represses the expression of contractile proteins and thereby inhibits contraction of VSMCs (26). miR-126 regulates angiogenesis (65). miR-21, miR-221, and miR-222 trigger VSMC proliferation (8, 11). Additionally, miR-21 may inhibit VSMC contraction based on predicted downstream targets, including myosin phosphatase and Rho interacting protein (M-RIP) (30, 47) and cofilin-2 (CFL-2) (1).

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and nitric oxide (NO), also known as endothelial-derived relaxant factor, are endogenous physiological VSMC relaxants and inhibitors of proliferation (18, 37). The principal receptors for both NO and ANP are guanylyl cyclases. NO-stimulated guanylyl cyclases are a ubiquitous family of heme-containing heterodimers (α- and β-subunits of ∼80 and 70 kDa, respectively) (17, 31, 36). The receptor for ANP is a membrane-bound homodimeric guanylyl cyclase (GC-A) (20). The primary intracellular effector for cGMP formed by these enzymes is cGMP-dependent kinase (cGK) (23, 54, 55, 63). VSMCs express cGK1α and cGK1β (14). cGK inhibitors have been shown to block the relaxation and inhibition of proliferation of VSMC by ANP and NO agonists (32, 61). Proteins phosphorylated by cGK, which have been implicated in smooth muscle cell relaxation, include inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type I-associated cGMP kinase substrate (5, 53), myosin phosphatase 1 (67), phosphodiesterase (PDE)-5 (50), cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel (64), RhoA (13), and vimentin (46).

The present studies were performed to determine whether miRs are regulated by and/or involved in signaling by ANP and NO in VSMCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP), isobutyl methyl xanthine (IBMX), Rp-8-bromo-β-phenyl-1,N2-ethenoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphothioate (Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPS), 8-bromo-cGMP, and ANP were purchased from Sigma Chemical. Human aortic smooth muscle cells were purchased from Life Line. Pre-miR control, control miR inhibitor, pre-miR-21 and anti-miR-21 inhibitor, and TaqMan miR assays were purchased from Applied Biosystems. A commercial kit for collagen gel lattice contraction assay was from Cell Biolabs. cGMP assay kit was purchased from Assay Designs.

Cell culture and transient transfections.

Human aortic smooth muscle cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Early passage cells (passage 3–6) were used throughout the studies. Cells were grown to 70% confluence in DMEM-10% fetal bovine serum and then switched to DMEM without serum for 24 h to maintain quiescence. Cells were cultured in low serum (2.5%) containing DMEM. Transfections with 50 nM each of pre-miRs and anti-miR inhibitors were performed with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as per manufacturer's instructions.

cGMP assay.

Intracellular cGMP was measured as previously described (34). Cultured human VSMCs (HVSMCs) pretreated with IBMX (100 μM, 30 min) were incubated with ANP (10 nM, 4 h) and SNAP (100 μM, 4 h). Cells were lysed with 0.1 N HCl. cGMP was measured using a commercially available enzyme immunoassay kit purchased from Assay Design (Ann Arbor, MI). cGMP was normalized to total protein determined by Bradford.

miR microarray assay.

miR microarray assay was performed as described (25). Fluorescence images were collected using a laser scanner (GenePix 4000B, Molecular Device) and digitized using Array-Pro image analysis software (Media Cybernetics). Data were analyzed by first subtracting the background and then normalizing the signals using a LOWESS filter (locally-weighted regression). For two-color experiments, the ratio of the two sets of detected signals (log2 transformed, balanced) and P values of the t-test were calculated; differentially detected signals were those with <0.01 P values.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR for mature miRs-21, -26b, -98, and -1826 was performed on cDNA generated from 50 ng of total RNA using the protocol of the TaqMan miR assays (Applied Biosystem). Amplification and detection of specific products were performed with a Light Cycler 480 detection system (Roche Applied Science). As an internal control, small nuclear RNA 48 (RNU48) was used for miR template normalization. Fluorescent signals were normalized to an internal reference, and the threshold cycle (Ct) was set within the exponential phase of the PCR. The relative gene expression was calculated by comparing cycle times for each target PCR. The target PCR Ct values were normalized by subtracting the RNU48 Ct value, which provided the ΔCt value. The relative expression level between treatments was then calculated using the following equation: relative gene expression = 2−(ΔCtsample−ΔCtcontrol).

Collagen gel lattice contraction assay.

A standard kit assay was used (Cell Biolabs) (43). Two parts of cells were mixed with eight parts of collagen gel lattice mixture and plated for 1 h at 37°C. After the gel was polymerized (∼1 h), 1 ml of medium was added and incubated for 2 days. Next the gels were released from the sides of wells, and 24 h later the images were taken at various time points. The area of the gel lattices was determined with Image J software, and the relative lattice area was obtained by dividing the area of the well 24 h after detachment by the initial area of the well.

Proliferation assay.

Proliferation assay was performed using CellTiter 96 aqueous nonradioactive cell proliferation assay kit form Promega. This assay is a colorimetric method in which 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium inner salt is bioreduced by cells into a formazon product that is soluble in tissue culture medium and can be measured at 490 nm.

Western blot analysis.

Equal amounts of protein were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and then blocked in a Tris-buffered saline-Tween (TBS-T) solution (20 mM Tris, 140 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.6) with 5% nonfat milk. After two washes, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies such as anti-mouse monoclonal CFL-2 (1:500), anti-rabbit polyclonal M-RIP (1:500), monoclonal cGK-1 (1:500), or monoclonal tubulin (1:1,000) antibodies. The membrane was then washed three times in TBS-T and incubated for 1 h with peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at a dilution of 1:2,000 in TBS-T. After three additional washes in TBS-T, the membrane was incubated for 1 min with ECL detection reagents (Amersham) and exposed to X-ray film (Kodak) for varying times to obtain desirable band intensity within linear range and optimal saturation. The bands were quantified by National Institutes of Health image analysis. For analysis, band densities were normalized to tubulin.

Identification of miR-21 targets.

We used several computational algorithms, including target scan, Pic Tar, miR data base, and miRgen, and searched for evolutionarily conserved targets (21, 35).

Statistics.

Values are expressed as means ± SD. Differences among groups are determined by ANOVA two-factor for repeated measurements. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

ANP- and SNAP-induced changes in miRNAs.

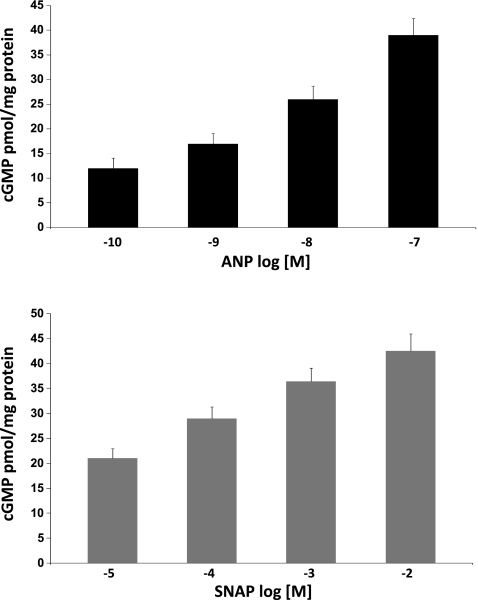

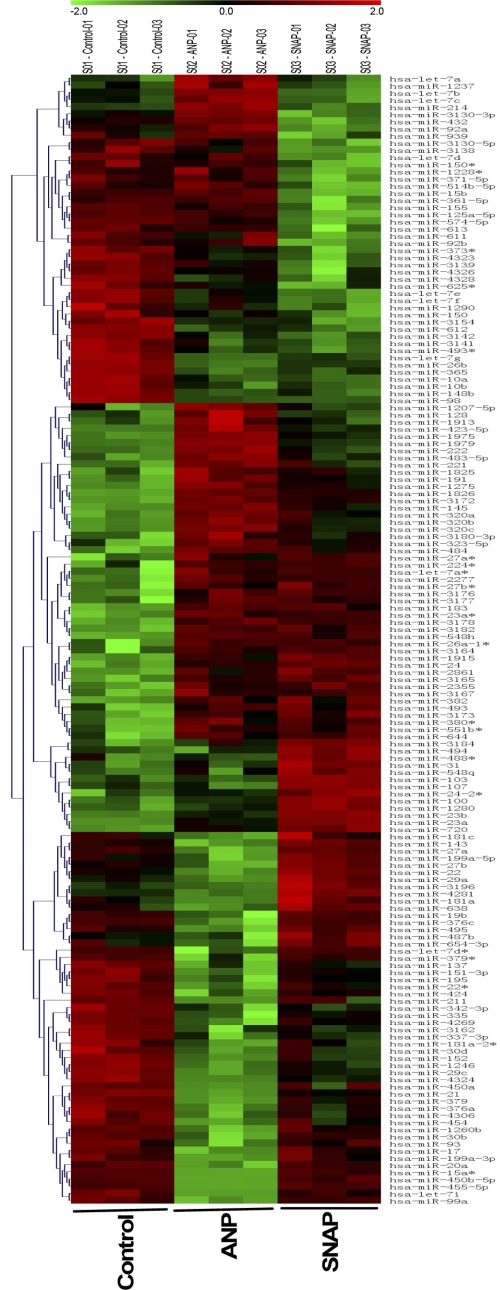

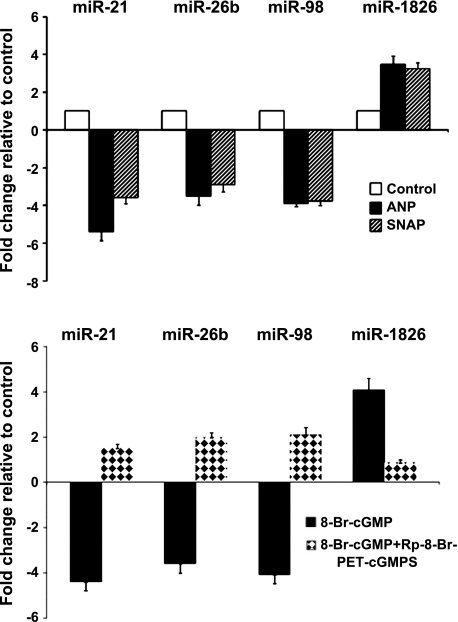

HVSMCs were incubated with broad spectrum PDE inhibitor, IBMX (100 μM × 30 min) to prevent the degradation of cGMP by PDEs followed by ANP (10 nM, 4 h) or NO donor, SNAP (100 μM, 4 h). Under these conditions, ANP and SNAP produced equal increases in intracellular cGMP (Fig. 1). miRNAs were isolated and subjected to microarray analysis using human miRNA microarray Sanger version 15. Out of 1,090 miRNAs arrayed, 22 shared miRs were upregulated and 21 shared miRs were downregulated by both ANP and SNAP (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2, Table 1). ANP upregulated six and downregulated seven miRs compared with that of SNAP treatment (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Four miRs, miR-21, miR-26b, miR-98, and miR-1826, had the greatest change in expression, as determined by miR microarray analysis, and were confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3, top, P < 0.01). Although miR-98 showed greater reduction in expression than that of miR-21, we pursued with miR-21, as it has been widely implicated in cardiovascular disorders.

Fig. 1.

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) dose-response curves for intracellular cGMP. Human vascular smooth muscle cells (HVSMCs) were pretreated with isobutyl methyl xanthine (IBMX; 100 μM, 30 min) and incubated with ANP (10−7-10−10 M, 4 h; top) and SNAP (10−2-10−5 M, 4 h; bottom). Cells were harvested, and cell lysates are subjected to cGMP assay, as described in materials and methods. Values are means ± SD; n = 4.

Fig. 2.

microRNA (miR) microarray analysis of control and ANP- and SNAP-treated HVSMC. miRs were extracted from HVSMC cells treated with either ANP (10 nM, 4 h) or SNAP (100 μM, 4 h). Microarray analysis was performed (materials and methods). The color bar on the top conveys changes in miR expression, with green and red indicating minimal and maximal expression of miRs, respectively. The samples from left to right are control lanes-3, ANP-3 lanes, and SNAP-3 lanes. The identifications of miRs are shown on the right. n = 3 for each treatment. P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Aberrant expression of miRs by ANP and SNAP in HVSMC

| Name of miR | ANP | SNAP |

|---|---|---|

| miRs downregulated by ANP and SNAP | ||

| 21 | 8.8 | 4 |

| 98 | 29.7 | 37 |

| 26b | 7.7 | 4.8 |

| 4324 | 3 | 2.9 |

| 7g | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| 99a | 4.2 | 2.2 |

| 125-5p | 2.6 | 2.9 |

| 29c | 8.4 | 3.3 |

| 7e | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| 1246 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

| 10a | 2.6 | 2.9 |

| 7f | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 1260b | 3.2 | 2.2 |

| 152 | 2.8 | 2.3 |

| 199a-3p | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| 7d | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| 335 | 36.7 | 6.04 |

| 7i | 2.7 | 2.3 |

| 10b | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| 145 | 2.8 | 2.4 |

| 143 | 2.3 | 1.9 |

| miRs upregulated by ANP and SNAP | ||

| 1826 | 9.6 | 5.1 |

| 23a | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| 23b | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| 1979 | 9.5 | 2.5 |

| 3172 | 3.4 | 2.4 |

| 720 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| 1975 | 3.9 | 2.7 |

| 24 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| 3178 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| 320c | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| 7c | 2.3 | 2.07 |

| 100 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| 423-5p | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| 1915 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 1275 | 2.5 | 1.98 |

| 222 | 3.2 | 2.1 |

| 1280 | 2.2 | 2.4 |

| 103 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| 320b | 1.98 | 2.2 |

| 2861 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| 31 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| 221 | 2.4 | 2.04 |

Fold expression of different microRNAs (miRs) regulated by atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP)- and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-treated human vascular smooth muscle cells (HVSMCs); n = 3 for each group. P < 0.05 in ANOVA analysis vs. control.

Table 2.

miRs regulated by ANP but not SNAP

| Upregulated miRs by ANP | Downregulated miRs by ANP |

|---|---|

| miR-22 | |

| miR-15b | miR-4281 |

| miR-214 | miR-27a |

| miR-7b | miR-3196 |

| miR-92a | miR-29a |

| miR-7c | miR-27b |

| miR-92b | miR-638 |

Fig. 3.

Validation of SNAP- and ANP-mediated changes and the role of cGMP-dependent kinase (cGK) in the expression of miR-21 in HVSMCs by quantitative RT (qRT)-PCR. Total RNA isolated from control and ANP- and SNAP-treated cGMP (top) analog 8-bromo-cGMP (8-Br-cGMP)-treated (bottom) and cGK inhibitor β-phenyl-1,N2-etheno-8-bromo-cGMP-treated HVSMC were subjected to qRT-PCR using TaqMan miR assays (materials and methods). For cGK inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated with Rp-8-bromo-β-phenyl-1,N2-ethenoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphothioate (Rp-8-Br-PET-CGMPS) (25 μM × 30 min), followed by treatment with 8-Br-cGMP. The fold change in the expression of the miR-21, as indicated on the X-axis, is relative to that of control cells. Values are means ± SD; n = 4. P < 0.01 compared with control.

ANP- and SNAP-induced changes in miRNA expression are mediated by cGMP signaling.

To determine whether miRs regulated by SNAP and ANP are dependent on cGMP and cGK signaling, the effects of the 8-bromo-cGMP, a cell-permeable form of cGMP, and the cGK-specific inhibitor Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPS on ANP- and SNAP- induced changes in miRs-21, -26b, -98, and -1826 abundance were examined. Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPS (25 μM × 30 min) increased miR-21, miR-98, and miR-26b levels and reduced miR-1826 levels significantly (Fig. 3, bottom, Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMP). Treatment of VSMCs with 8-bromo-cGMP (100 μM × 30 min) decreased the expression of miRs-21, -26b, and -98, and increased the expression of miR-1826 expression (Fig. 3, bottom, 8-bromo-cGMP). Together, this indicates that the SNAP- and ANP-mediated changes in miR expression are dependent on cGMP/cGK signaling in the cell.

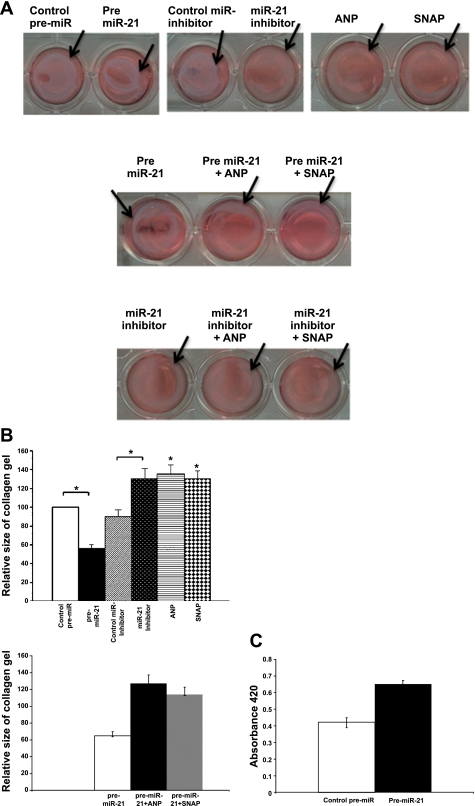

miR-21 contracts HVSMCs.

To determine the effect of miR-21 on contractility, HVSMCs were transfected with either 1) precursor miR-21 (pre-miR-21) (50 nM, 48 h), or 2) anti-miR-21 inhibitor (50 nM, 48 h). Contractility was measured using a collagen gel lattice contraction assay. Negative control miRs (precursor miR and anti-miR inhibitor) did not significantly affect contraction. Pre-miR-21 caused contraction of HVSMC by 51 ± 4.9% and anti-miR-21 inhibitor enhanced relaxation of HVSMC by 43 ± 6.8% (Fig. 4, A and B, top panels, P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

miR-21-mediated contraction of HVSMCs. HVSMC were transfected with pre-miR-21, anti-miR-21 inhibitor, or controls (pre-miR, anti-miR inhibitor), as indicated, and then embedded in the collagen gels and subjected to a contraction assay (see materials and methods). Representative images (A) and summarized data (B) are as follows. A and B, top: the effect of pre-miR-21 and anti-mir-21 inhibitor on HVSMC transfected with pre-miR-21 and anti-miR-21 inhibitor. A, middle, and B, bottom: the effect of ANP and SNAP on pre-miR-21-induced contraction of HVSMC transfected with pre-miR-21 and treated with ANP and SNAP. A, bottom: the effect of ANP and SNAP on anti-miR-21 inhibitor-induced relaxation of HVSMC transfected with anti-miR-21 inhibitor and treated with ANP and SNAP (arrow: lattice border). n = 4. P < 0.05. C: miR-21 promotes proliferation of HVSMC. HVSMCs transfected with pre-miR control and pre-miR-21 (as described above) are subjected to proliferation assay using a kit from Promega. Values are means ± SD; n = 4. P < 0.05.

In a second set of experiments, the role of miR-21 in ANP- and SNAP-mediated decreases in VSMC contractility was determined. ANP (10 nM, 4 h) and SNAP (100 μM, 4 h) induced relaxation of HVSMC by 48 ± 7.9% and 44.2 ± 6.5%, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B, top panels, P < 0.05). Treatment of the HVSMC with ANP and SNAP blocked contraction by pre-miR-21 by 39.5 ± 5.2% and 32.7 ± 4.9% (Fig. 4, A, middle panel, and B, bottom panel). In anti-miR-21 inhibitor-treated cells, the effect of ANP and SNAP was marginal and not significant (Fig. 4A, bottom panel).

Since miR-21 has been widely implicated in VSMC proliferation, we next examined whether miR-21 has any effect on HVSMC proliferation. Pre-miR-21 increased HVSMC proliferation compared with that of control pre-miR (Fig. 4C, P < 0.05).

Identification and empirical confirmation of miR-21 target genes.

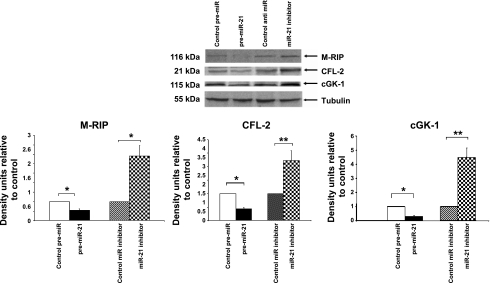

Computational algorithms, including target scan (www.targetscan.org), Pic Tar (pictar.mdc-berlin.de), miR data base (mirdb.org/miRDB/), and miRgen (diana.pcbi.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/miRGen/v3/Targets.cgi), were used to identify evolutionarily conserved targets (21, 35). Novel potential targets of miR-21 identified include M-RIP (30) and CFL-2 (1). To empirically evaluate these targets, HVSMC were transfected with pre-miR-21- and miR-21-specific inhibitor for 48 h, and protein levels of M-RIP and CFL-2 were analyzed by Western blot analysis. Pre-miR-21 decreased (P < 0.05) the expression of M-RIP and CFL-2 (2.5- and 2-fold), respectively, and miR-21 inhibitor increased M-RIP and CFL-2 expression (2.5- and 3.5-fold, respectively) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Pre-miR21 and miR-21 inhibitor decreased and increased myosin phosphatase and Rho interacting protein (M-RIP), cofilin-2 (CFL-2), and cGK-1 expression, respectively. Cells were transfected with pre-miR control, pre-miR-21, miR inhibitor control, and miR-21 inhibitor (50 nM each). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell lysates were analyzed for expression of M-RIP, cGK-1, and CFL2 by Western blot analysis with polyclonal antibody to M-RIP and monoclonal antibodies to CFL-2 and cGK-1 (materials and methods). A representative Western blot is shown. Values are means ± SD; n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with control.

miRs often mediate feedback loops (4). We examined whether miR-21 has any effect on cGMP/cGK signaling. Computer algorithms predicted cGK1 as one of the targets of miR-21. Western blot analysis on the extracts prepared from cells transfected with pre-miR-21 and anti-miR-21 decreased and increased the expression of cGK1 compared with those of their respective controls (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

In the present studies, miRNA microarray profiling identified 22 and 21 shared miRs whose expression was increased and decreased, respectively, by both SNAP and ANP in HVSMC. Out of these miRs, four are regulated similarly by ANP and SNAP and are cGMP/cGK dependent. These miRs target genes important for HVSMC contraction (Table 3). Thus our studies provide an ensemble of functional miRs regulated by ANP and SNAP that play a role in VSMC relaxation.

Table 3.

Potential targets of miRs-21, -26b, -98, and -1826 and their cellular functions based on computational analysis

| miR | Potential Targets | Putative Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | Cofilin-2 (CFL-2) | Actin dynamics (1) |

| Myosin phosphatase and interacting protein (M-RIP) | Myosin light chain dephosphorylation, regulation of actin fibers, and smooth muscle cell (SMC) relaxation (42, 47) | |

| ARHGAP24/p73RHOGAP | Negative regulators of signaling (27, 44, 57) | |

| miR-26b | M-RIP | Myosin light chain dephosphorylation, regulation of actin fibers, and SMC relaxation (30, 60) |

| Myosin phosphatase | Regulation of HVSMC contraction (38, 59) | |

| Sling shot homolog 2 (SSH2) | Activator of cofilin and mediator of actin dynamics (12) | |

| miR-98 | Myosin phosphatase | Regulation of HVSMC contraction (67) |

| Sling shot homolog 1 (SSH1) | Activator of cofilin and mediator of actin dynamics (52) | |

| miR-1826 | CDC42 | Regulation of actin polymerization (40, 48, 71) |

| Calmodulin 2 (CALM2) | Calcium sensor and calcium signal modulator (67) | |

| MAP kinase kinase 1 (MAP2K1) | HVSMC contraction (51) |

Nos. in parentheses, ref. nos.

Six and seven miRs are up- and downregulated by ANP only, but not SNAP (Table 2). Some of these have functional significance. miR-92 plays a role in heart failure (58), and miR-15 has been implicated in cardiovascular disorders (15). Myocardial expression of miR-27b is increased during heart development (9), and miR-29a plays an important role in heart remodeling and reverse remodeling (66). However, the role of these miRs in vascular biology is yet to be determined.

We report that the expression of four miRs, i.e., miRs-21, -26b, -98, and -1826 is regulated by ANP/NO signaling via cGK. We focused on miR-21 in the present study, as it plays a pivotal role in cardiovascular disorders. miR-21 expression is downregulated by ANP/NO/cGK signaling, and miR-21 enhances SMC contractility in a collagen gel contraction assays, likely through inhibiting the expression of proteins important for VSMC relaxation. The present results are the first to implicate miRs in general and miR-21 in particular in ANP and NO signaling.

Our results suggest that the regulation of the expression of miRs by both NO and ANP signaling is dependent on cGMP/cGK. The mechanism underlying the regulation of miRs by cGK may involve phosphorylation of RNA binding proteins, such as hnRNPA1, that specifically binds to the terminal loop region of miRs and regulates its processing (41). In agreement with this is the finding that SMAD-1, -3, and -5 interact with p68 RNA helicase subunit to enhance processing of primary miR-21 transcript in VSMC stimulated with transforming growth factor-β (10). Alternatively 3′ adenylation of miRs by poly A polymerase might stabilize those miRs (28).

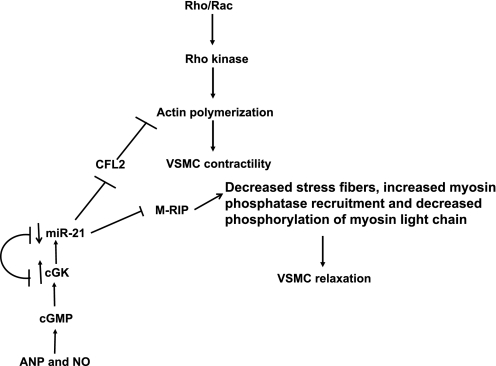

The present results also show that miR-21 contracts smooth muscle cells. ANP and SNAP abrogate miR-21-induced HVSMC contraction. miR-21-induced HVSMC contraction is likely mediated by its effect on target genes. Therefore, we identified the targets by computational algorithms, such as target scan, Pic Tar, miR database, and miRgen, which include M-RIP (30) and CFL-2. These targets are empirically confirmed by Western blotting. The identified targets have been shown to relax VSMC. CFL-2 has been shown to relax VSMC by inhibiting actin polymerization (29, 39). M-RIP induces VSMC relaxation by reducing actin stress fibers, recruiting myosin light chain phosphatase to the stress fibers, where it dephosphorylates myosin light chain, leading to VSMC relaxation (30, 47). ANP and SNAP blocked miR-21-induced HVSMC contraction. Since cGK1 is the target of miR-21 (Fig. 5), we presume that ANP/cGMP/cGK and SNAP/cGMP/cGK reduce the expression of miR-21, inhibiting the effect of miR-21 on cGK1 expression, and increasing the expression of miR-21 targets to facilitate HVSMC relaxation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Molecular pathway by which miR-21 regulates HVSMC contraction. ANP and SNAP via cGMP/cGK signaling reduce the expression of miR-21, which has a feedback loop inhibitory effect on cGK-1. miR-21 targets (CFL-2, M-RIP, and cGK-1) and their effects on HVSMC contraction/relaxation are depicted. NO, nitric oxide.

We show that miR-21 promotes HVSMC contraction (Fig. 4, A and B) and proliferation (Fig. 4C). Similarly, ghrelin, a natural ligand of growth hormone secretagogue receptor, inhibits angiotensin II-induced contraction and proliferation of human aortic smooth muscle cells (49). miR-21 has been reported to trigger HVSMC proliferation by downregulating proapoptotic genes, e.g., programmed cell death-4 and phosphatase and tensin homology deleted from chromosome 10 (25, 70) and induce cardiomyocyte growth by targeting sprouty-1 (62).

Since miR-21 increases VSMC contraction, we presume that it plays a role in the regulation of vascular tone and arterial blood pressure. There are lines of evidence that miR-21 plays a key role in cardiovascular disorders, such as proliferative vascular disease, cardiac hypertrophy, and heart failure (8). Asymmetric dimethylarginine, an endogenous NO synthase inhibitor, has been reported to increase miR-21 expression in angiogenic progenitor cells (16). miR-21 levels are increased in mouse hearts at 7, 14, and 21 days after aortic banding and in cultured neonatal hypertrophic cardiomyocytes stimulated by angiotensin II or phenylephrine (6). miR-21 levels have been reported to be increased in rat hearts at 6 and 24 h after acute myocardial infarction(8). Cardiac stress induced in vitro by hydrogen peroxide treatment in neonatal cardiomyocytes resulted in the upregulation of miR-21 levels (7). miR-21 levels are elevated in cardiac fibrosis in pressure-overload mouse model, and knockdown of miR-21 by miR-21 inhibitor subdued interstitial fibrosis and improved cardiac function by activating sprouty-1, a negative regulator of ERK-MAP kinase pathway (62). However, recently, it has been shown that miR-21 null mice are normal, and miR-21 is not essential for pathological cardiac remodeling in rodents (45). Further studies will be performed with other types of vascular cells, such as coronary artery smooth muscle cells and A10 rat VSMCs to strengthen the effect of NO and ANP on miR expression in VSMC.

Growing lines of evidence suggest that miR-21 plays a key role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disorders. Our findings that miR-21 regulates VSMC contraction raises a possibility that miR-21 could be a potential therapeutic target for hypertension.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants K01 DK071641-01 and 3 K01 DK071641-01-S1 (to K. U. Kotlo) and NIH Grant R21HL096031-01A1 and Veterans Administration Merit Review (to R. S. Danziger).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate helpful discussions with Dr. Randal Skidgel.

REFERENCES

- 1. Albinsson S, Nordstrom I, Hellstrand P. Stretch of the vascular wall induces smooth muscle differentiation by promoting actin polymerization. J Biol Chem 279: 34849–34855, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455: 64–71, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beezhold KJ, Castranova V, Chen F. Microprocessor of microRNAs: regulation and potential for therapeutic intervention. Mol Cancer 9: 134, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brabletz S, Brabletz T. The ZEB/miR-200 feedback loop–a motor of cellular plasticity in development and cancer? EMBO Rep 11: 670–677, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Casteel DE, Zhang T, Zhuang S, Pilz RB. cGMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring by IRAG regulates its nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity. Cell Signal 20: 1392–1399, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng Y, Ji R, Yue J, Yang J, Liu X, Chen H, Dean DB, Zhang C. MicroRNAs are aberrantly expressed in hypertrophic heart: do they play a role in cardiac hypertrophy? Am J Pathol 170: 1831–1840, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng Y, Liu X, Zhang S, Lin Y, Yang J, Zhang C. MicroRNA-21 protects against the H(2)O(2)-induced injury on cardiac myocytes via its target gene PDCD4. J Mol Cell Cardiol 47: 5–14, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng Y, Zhang C. MicroRNA-21 in cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 3: 251–255, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chinchilla A, Lozano E, Daimi H, Esteban FJ, Crist C, Aranega AE, Franco D. MicroRNA profiling during mouse ventricular maturation: a role for miR-27 modulating Mef2c expression. Cardiovasc Res 89: 98–108, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Lagna G, Hata A. SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature 454: 56–61, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Nguyen PH, Lagna G, Hata A. Induction of microRNA-221 by platelet-derived growth factor signaling is critical for modulation of vascular smooth muscle phenotype. J Biol Chem 284: 3728–3738, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eiseler T, Doppler H, Yan IK, Kitatani K, Mizuno K, Storz P. Protein kinase D1 regulates cofilin-mediated F-actin reorganization and cell motility through slingshot. Nat Cell Biol 11: 545–556, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ellerbroek SM, Wennerberg K, Burridge K. Serine phosphorylation negatively regulates RhoA in vivo. J Biol Chem 278: 19023–19031, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feil R, Gappa N, Rutz M, Schlossmann J, Rose CR, Konnerth A, Brummer S, Kuhbandner S, Hofmann F. Functional reconstitution of vascular smooth muscle cells with cGMP-dependent protein kinase I isoforms. Circ Res 90: 1080–1086, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Finnerty JR, Wang WX, Hebert SS, Wilfred BR, Mao G, Nelson PT. The miR-15/107 group of microRNA genes: evolutionary biology, cellular functions, and roles in human diseases. J Mol Biol 402: 491–509, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fleissner F, Jazbutyte V, Fiedler J, Gupta SK, Yin X, Xu Q, Galuppo P, Kneitz S, Mayr M, Ertl G, Bauersachs J, Thum T. Short communication: asymmetric dimethylarginine impairs angiogenic progenitor cell function in patients with coronary artery disease through a microRNA-21-dependent mechanism. Circ Res 107: 138–143, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Foerster J, Harteneck C, Malkewitz J, Schultz G, Koesling D. A functional heme-binding site of soluble guanylyl cyclase requires intact N-termini of alpha 1 and beta 1 subunits. Eur J Biochem 240: 380–386, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Friebe A, Koesling D. Regulation of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Circ Res 93: 96–105, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frost RJ, van Rooij E. miRNAs as therapeutic targets in ischemic heart disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 3: 280–289, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garbers DL, Koesling D, Schultz G. Guanylyl cyclase receptors. Mol Biol Cell 5: 1–5, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell 27: 91–105, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Herranz H, Cohen SM. MicroRNAs and gene regulatory networks: managing the impact of noise in biological systems. Genes Dev 24: 1339–1344, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hofmann F, Ammendola A, Schlossmann J. Rising behind NO: cGMP-dependent protein kinases. J Cell Sci 113: 1671–1676, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jackson A, Linsley PS. The therapeutic potential of microRNA modulation. Discov Med 9: 311–318, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ji R, Cheng Y, Yue J, Yang J, Liu X, Chen H, Dean DB, Zhang C. MicroRNA expression signature and antisense-mediated depletion reveal an essential role of MicroRNA in vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ Res 100: 1579–1588, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jiang Y, Yin H, Zheng XL. MicroRNA-1 inhibits myocardin-induced contractility of human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 225: 506–511, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Katoh M. Identification and characterization of ARHGAP24 and ARHGAP25 genes in silico. Int J Mol Med 14: 333–338, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Katoh T, Sakaguchi Y, Miyauchi K, Suzuki T, Kashiwabara S, Baba T. Selective stabilization of mammalian microRNAs by 3′ adenylation mediated by the cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase GLD-2. Genes Dev 23: 433–438, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaunas R, Nguyen P, Usami S, Chien S. Cooperative effects of Rho and mechanical stretch on stress fiber organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 15895–15900, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koga Y, Ikebe M. p116Rip decreases myosin II phosphorylation by activating myosin light chain phosphatase and by inactivating RhoA. J Biol Chem 280: 4983–4991, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koglin M, Behrends S. Native human nitric oxide sensitive guanylyl cyclase: purification and characterization. Biochem Pharmacol 67: 1579–1585, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Komalavilas P, Shah PK, Jo H, Lincoln TM. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways by cyclic GMP and cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in contractile vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 274: 34301–34309, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kota SK, Balasubramanian S. Cancer therapy via modulation of micro RNA levels: a promising future. Drug Discov Today 15: 733–740, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kotlo KU, Rasenick MM, Danziger RS. Evidence for cross-talk between atrial natriuretic peptide and nitric oxide receptors. Mol Cell Biochem 338: 183–189, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet 37: 495–500, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krumenacker JS, Hanafy KA, Murad F. Regulation of nitric oxide and soluble guanylyl cyclase. Brain Res Bull 62: 505–515, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kuhn M. Structure, regulation, and function of mammalian membrane guanylyl cyclase receptors, with a focus on guanylyl cyclase-A. Circ Res 93: 700–709, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee MR, Li L, Kitazawa T. Cyclic GMP causes Ca2+ desensitization in vascular smooth muscle by activating the myosin light chain phosphatase. J Biol Chem 272: 5063–5068, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee S, Helfman DM. Cytoplasmic p21Cip1 is involved in Ras-induced inhibition of the ROCK/LIMK/cofilin pathway. J Biol Chem 279: 1885–1891, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Machesky LM, Insall RH. Signaling to actin dynamics. J Cell Biol 146: 267–272, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Michlewski G, Guil S, Semple CA, Caceres JF. Posttranscriptional regulation of miRNAs harboring conserved terminal loops. Mol Cell 32: 383–393, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mulder J, Ariaens A, van den Boomen D, Moolenaar WH. p116Rip targets myosin phosphatase to the actin cytoskeleton and is essential for RhoA/ROCK-regulated neuritogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 15: 5516–5527, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ngo P, Ramalingam P, Phillips JA, Furuta GT. Collagen gel contraction assay. Methods Mol Biol 341: 103–109, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ohta Y, Hartwig JH, Stossel TP. FilGAP, a Rho- and ROCK-regulated GAP for Rac binds filamin A to control actin remodelling. Nat Cell Biol 8: 803–814, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patrick DM, Montgomery RL, Qi X, Obad S, Kauppinen S, Hill JA, van Rooij E, Olson EN. Stress-dependent cardiac remodeling occurs in the absence of microRNA-21 in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 3912–3916, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pryzwansky KB, Wyatt TA, Lincoln TM. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase is targeted to intermediate filaments and phosphorylates vimentin in A23187-stimulated human neutrophils. Blood 85: 222–230, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Riddick N, Ohtani K, Surks HK. Targeting by myosin phosphatase-RhoA interacting protein mediates RhoA/ROCK regulation of myosin phosphatase. J Cell Biochem 103: 1158–1170, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rohatgi R, Ma L, Miki H, Lopez M, Kirchhausen T, Takenawa T, Kirschner MW. The interaction between N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex links Cdc42-dependent signals to actin assembly. Cell 97: 221–231, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rossi F, Castelli A, Bianco MJ, Bertone C, Brama M, Santiemma V. Ghrelin inhibits contraction and proliferation of human aortic smooth muscle cells by cAMP/PKA pathway activation. Atherosclerosis 203: 97–104, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rybalkin SD, Rybalkina IG, Feil R, Hofmann F, Beavo JA. Regulation of cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase (PDE5) phosphorylation in smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 277: 3310–3317, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Salamanca DA, Khalil RA. Protein kinase C isoforms as specific targets for modulation of vascular smooth muscle function in hypertension. Biochem Pharmacol 70: 1537–1547, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. San Martin A, Lee MY, Williams HC, Mizuno K, Lassegue B, Griendling KK. Dual regulation of cofilin activity by LIM kinase and Slingshot-1L phosphatase controls platelet-derived growth factor-induced migration of human aortic smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 102: 432–438, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schlossmann J, Ammendola A, Ashman K, Zong X, Huber A, Neubauer G, Wang GX, Allescher HD, Korth M, Wilm M, Hofmann F, Ruth P. Regulation of intracellular calcium by a signalling complex of IRAG, IP3 receptor and cGMP kinase Ibeta. Nature 404: 197–201, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schlossmann J, Desch M. cGK substrates. Hand Exp Pharmacol 191: 163–193, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schlossmann J, Feil R, Hofmann F. Signaling through NO and cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Ann Med 35: 21–27, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shomron N. MicroRNAs and pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics 11: 629–632, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Su ZJ, Hahn CN, Goodall GJ, Reck NM, Leske AF, Davy A, Kremmidiotis G, Vadas MA, Gamble JR. A vascular cell-restricted RhoGAP, p73RhoGAP, is a key regulator of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 12212–12217, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sucharov C, Bristow MR, Port JD. miRNA expression in the failing human heart: functional correlates. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 185–192, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Surks HK, Mochizuki N, Kasai Y, Georgescu SP, Tang KM, Ito M, Lincoln TM, Mendelsohn ME. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by a specific interaction with cGMP- dependent protein kinase Ialpha. Science 286: 1583–1587, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Surks HK, Richards CT, Mendelsohn ME. Myosin phosphatase-Rho interacting protein. A new member of the myosin phosphatase complex that directly binds. RhoA J Biol Chem 278: 51484–51493, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Taylor MS, Okwuchukwuasanya C, Nickl CK, Tegge W, Brayden JE, Dostmann WR. Inhibition of cGMP-dependent protein kinase by the cell-permeable peptide DT-2 reveals a novel mechanism of vasoregulation. Mol Pharmacol 65: 1111–1119, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, Galuppo P, Just S, Rottbauer W, Frantz S, Castoldi M, Soutschek J, Koteliansky V, Rosenwald A, Basson MA, Licht JD, Pena JT, Rouhanifard SH, Muckenthaler MU, Tuschl T, Martin GR, Bauersachs J, Engelhardt S. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 456: 980–984, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vaandrager AB, de Jonge HR. Signalling by cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Mol Cell Biochem 157: 23–30, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vaandrager AB, Smolenski A, Tilly BC, Houtsmuller AB, Ehlert EM, Bot AG, Edixhoven M, Boomaars WE, Lohmann SM, de Jonge HR. Membrane targeting of cGMP-dependent protein kinase is required for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl- channel activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 1466–1471, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. van Solingen C, Seghers L, Bijkerk R, Duijs JM, Roeten MK, van Oeveren-Rietdijk AM, Baelde HJ, Monge M, Vos JB, de Boer HC, Quax PH, Rabelink TJ, van Zonneveld AJ. Antagomir-mediated silencing of endothelial cell specific microRNA-126 impairs ischemia-induced angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med 13: 1577–1585, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang J, Xu R, Lin F, Zhang S, Zhang G, Hu S, Zheng Z. MicroRNA: novel regulators involved in the remodeling and reverse remodeling of the heart. Cardiology 113: 81–88, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wooldridge AA, MacDonald JA, Erdodi F, Ma C, Borman MA, Hartshorne DJ, Haystead TA. Smooth muscle phosphatase is regulated in vivo by exclusion of phosphorylation of threonine 696 of MYPT1 by phosphorylation of Serine 695 in response to cyclic nucleotides. J Biol Chem 279: 34496–34504, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Xin M, Small EM, Sutherland LB, Qi X, McAnally J, Plato CF, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. MicroRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and responsiveness of smooth muscle cells to injury. Genes Dev 23: 2166–2178, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang C. Novel functions for small RNA molecules. Curr Opin Mol Ther 11: 641–651, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang C. MicroRNAs in vascular biology and vascular disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 3: 235–240, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang W, Wu Y, Du L, Tang DD, Gunst SJ. Activation of the Arp2/3 complex by N-WASp is required for actin polymerization and contraction in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C1145–C1160, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]