Abstract

Background

The rise of evidence-based medicine may have implications for the doctor–patient interaction. In recent decades, a shift towards a more task-oriented approach in general practice indicates a development towards more standardised healthcare.

Objective

To examine whether this shift is accompanied by changes in perceived quality of doctor–patient communication.

Design

GP observers and patient observers performed quality assessments of Dutch General Practice consultations on hypertension videotaped in 1982–1984 and 2000–2001. In the first cohort (1982–1984) 81 patients were recorded by 23 GPs and in the second cohort (2000–2001) 108 patients were recorded by 108 GPs. The GP observers and patient observers rated the consultations on a scale from 1 to 10 on three quality dimensions: medical technical quality, psychosocial quality and quality of interpersonal behaviour. Multilevel regression analyses were used to test whether a change occurred over time.

Results

The findings showed a significant improvement over time on all three dimensions. There was no difference between the quality assessments of GP observers and patient observers. The three different dimensions were moderately to highly correlated and the assessments of GP observers showed less variability in the second cohort.

Conclusions

Hypertension consultations in general practice in the Netherlands received higher quality assessments by general practitioners and patients on medical technical quality, psychosocial quality and the quality of interpersonal behaviour in 2000–2001 as compared with the 1980s. The shift towards a more task-oriented approach in hypertension consultations does not seem to detract from individual attention for the patient. In addition, there is less variation between general practitioners in the quality assessments of more recent consultations. The next step in this line of research is to unravel the factors that determine patients' quality assessments of doctor–patient communication.

Article summary

Article focus

Doctor–patient communication in hypertension consultations has become more business-like and task-oriented in the past few decades.

Shifts in communication styles in general practice may have produced changes in quality assessments of doctor–patient communication by general practitioners and patients.

Key messages

Compared with 20 years earlier (1982–1984), hypertension consultations recorded in 2000–2001 received higher quality assessments by GP observers and patient observers on three distinct quality dimensions: medical technical quality, psychosocial quality and the quality of interpersonal behaviour.

There was less variation between general practitioners in the quality assessments of more recent consultations.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Videotaped real-life general practice consultations from two distinct periods were analysed, which means that the findings refer to actual behaviour in general practice.

The quality assessments were made according to the same protocol in both periods.

Assessments of the GPs were executed by contemporary peers, while the assessments of patients were performed retrospectively. However, the concurrence of assessments of patient observers and GP observers in their different contexts reinforces our conclusions.

The generalisability of the findings is restricted to hypertension consultations, which involve a high proportion of repeat visits.

Introduction

General practice is evolving and the rise of evidence-based medicine may have implications for doctor–patient interactions.1–6 Studies have found that doctor–patient communication has become more task-oriented.7 Non-verbal aspects such as eye contact and body posture have changed in the past few decades.8 It has been suggested that these changes may be related to a development towards more standardised healthcare, based on protocols and guidelines.7 9 10 Simultaneously, the curriculum of professional training has undergone some major revisions, focusing on training in communication skills.11 12 However, there may be some tension between the development of standardised care and individual attention to patients.4 13 14 In this study, we examined whether the shift towards more standardised and task-oriented care in general practice has produced changes in the quality of doctor–patient communication as assessed by general practitioners and patients.

Quality of doctor–patient communication is a multidimensional concept which includes both medical technical and psychosocial aspects but also involves facets of the interaction. We focused on hypertension in general practice, since this is a common health problem and these three dimensions of quality are clearly identifiable when dealing with hypertension care. Hypertension care depends on the quality of medical technical aspects and also on psychosocial components.15 Hypertension is a risk factor for coronary heart disease, and is sensitive to stress and psychological disorders.16 The quality of the doctor–patient interaction also determines patients' active participation and encourages self-management skills that are necessary when dealing with hypertension.17 18 Moreover, fostering the doctor–patient relationship is considered an essential and universal value within medical practice.19–21

Since clinical guidelines are widely implemented in professionals' daily practice, it is expected that they may serve as a yardstick for general practitioners to measure the quality of the doctor–patient interaction. In contrast, most patients are not fully aware of these developments in general practice. Their perspective is different from that of professionals, and patients mainly base their quality assessments on experiential knowledge and may have different priorities and preferences than professionals.22–24 However, if the quality of the medical interaction has actually changed, patients should be able to perceive this change in doctor–patient communication over time.

Methods

We compared quality assessments of GP observers and patient observers across two time periods. The first cohort consists of consultations videotaped in 1982–1984 and the second, in 2000–2001.

Videotaped consultations

Based on the International Classification of Primary Care, we selected videotaped consultations with patients with hypertension (International Classification of Primary Care-codes K85-K87) from a larger dataset of two cohorts of random general practice consultations. The first cohort comprised all hypertension consultations selected from a random sample of 1569 videotaped consultation in 1982–1984 (n=103).7 25–27 However, owing to deterioration in the technical quality of some videotaped consultations, only 81 consultations (recorded by 23 GPs) were useable for the quality assessments. The second dataset was recorded in 2000–2001 (n=2794) and consisted also from a random sample of general practice consultations.7 28 From this dataset, we selected every first hypertension consultation from each of the 108 participating GPs (n=108).

The patients in the selected consultations showed no differences in age and gender between the two study samples. The mean age was 58.5 (SD=14.80) and 61.4 (SD=14.66) years, respectively (NS), and 65% versus 63% of the sample was female (NS). In both samples the vast majority of the consultations were repeat visits. All physicians in the selected consultations were specialised in general practice and the majority (92% vs 94%) had more than 5 years experience. In the first study sample (1982–1984), all the physicians (N=23) were male and in the second study sample (2000–2001), 80 physicians were male and 28 were female (74% vs 26%). In the Netherlands, routine care for patients with hypertension is delivered in general practice. The study was carried out in accordance with Dutch privacy legislation. All participating physicians and patients who were videotaped during their consultation gave their informed consent.

Quality assessment by general practitioners (GP observers)

In 1987, 12 GP observers (age 30–70; four female and eight male physicians) were asked to rate the selected consultations from the first cohort (videotaped in 1982–1984). These GP observers had a minimum of 5 years' experience in practice. The procedure in this first cohort of peer assessments has been described previously.15 In 2002, the second cohort of selected consultations (videotaped in 2000–2001) was individually rated by a new group of 12 GP observers (age 36–62; six female and six male physicians). These GP observers also had a minimum of 5 years' experience in practice. Both groups of GP observers were drawn from the Dutch National Register of General Practitioners and recruited by mail or telephone. None of the GP observers were in any way involved in the collected videotaped consultations.

In both cohorts, each consultation was observed and rated by all 12 GP observers on three dimensions of quality of care. A scale from 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent) was used. The dimensions assessed by the general practitioners were (1) medical technical quality of care, (2) psychosocial quality of care and (3) quality of interpersonal behaviour (doctor–patient relationship). The GP observers received a short training programme about the rating scale and the different dimensions of quality of care. For the assessments of the medical technical dimension, they were instructed to take into account the then current best practice for hypertension.29 30 The psychosocial dimension referred to the way non-somatic aspects related to the complaint were addressed, such as stress-related factors in the origin of hypertension and the psychosocial problems caused by hypertension or its treatment; and interpersonal quality referred exclusively to the way in which the GP succeeded in building an open and secure relationship with the patient. All GP observers signed a statement of confidentiality before starting the assessments.

Quality assessment by patient observers with hypertension

Patient observers with hypertension rated videotaped consultations of both cohorts individually in the period from April 2010 to July 2010. People were recruited through advertisements on health-related internet web pages and by flyers placed in healthcare settings (general practices, pharmacists). Participants who had previously been involved in other health research projects conducted by NIVEL were actively approached by mail. All patient observers met the following criteria: diagnosed with hypertension by a physician, consulted a general practitioner at least once in the past year, not involved in a healthcare-related lawsuit or legal complaint procedure and could understand and speak the Dutch language.

In total, 108 patient observers with hypertension (age 24–80; 73 female and 35 male observers) completed the patient assessments of the videotaped consultations. See table 1 for background characteristics of the patient observers. Each patient observer observed 8–12 consultations (randomly assigned from both cohorts, but with a total duration of approximately 90 min) in order for each consultation in the sample to be rated five or six times. The patient observers individually rated the same three dimensions of quality of care as the GP observers and received a comparable short training programme. For the medical technical dimension, patient observers were instructed to consider the clarity of any medical explanations given by the general practitioner. For the other two dimensions, they received the same instruction as the GP observers. We noticed that patients could easily relate to these aspects of hypertension care and were therefore capable of distinguishing all three dimensions based on their experiential knowledge. All patient observers signed a statement of confidentiality before starting the assessments.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the patient observers

| Background characteristics | Patient observers with hypertension (N=108) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 73 (68) |

| Male | 35 (32) |

| Age (years) | |

| <40 | 2 (2) |

| 40–49 | 12 (11) |

| 50–59 | 46 (43) |

| 60–69 | 39 (36) |

| 70–79 | 9 (8) |

| Education level | |

| Primary education | 2 (2) |

| Secondary education | 59 (54.5) |

| Third-level education | 47 (43.5) |

| Employment | |

| Retired | 35 (32) |

| Employed | 31 (29) |

| Self-employed | 5 (5) |

| Other (student, housewife, job seeker) | 37 (34) |

| Native background | |

| Dutch | 96 (89) |

| First-generation migrant | 6 (5.5) |

| Second-generation migrant | 6 (5.5) |

| Health | |

| Using medication for hypertension | 81 (75) |

| Comorbidity, other chronic disease | 50 (46) |

| Healthcare use | |

| Contact with GP in past 2 months | 76 (70) |

| Contact with medical specialist in past year | 72 (67) |

Results are shown as number (%)

Statistical analyses

To account for the multilevel structure of quality assessments nested within videotaped consultations and individual observers, multilevel regression analysis was applied. The categories cohort (0=1982–1984 and 1=2000–2001) and observer type (0= patient observers and 1= GP observers) were coded as dummy variables. First, the associations between the three dimensions of quality of care were examined. Second, it was tested whether a change over time in quality assessments occurred and whether the quality assessments of patient observers and GP observers were comparable.

Results

Associations between the three dimensions of quality of care

The quality assessments correlated positively between the three different dimensions of quality of care for each observation period and for GPs and patients as well (see table 2). Furthermore, analysis showed that the overall quality assessments of interpersonal behaviour were higher than for the medical technical dimension (T (5258)=2.79, p<0.01); and the medical technical dimension received higher quality assessments than the psychosocial dimension (T (5249)=6.80, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Associations (Pearson's r) between the three dimensions of quality of care

| Medical technical | Psychosocial | Interpersonal | |

| Cohort 1982–1984 | |||

| All quality assessments | |||

| Medical technical | – | ||

| Psychosocial | 0.66 | – | |

| Interpersonal | 0.63 | 0.80 | – |

| Assessments of GP observers | |||

| Medical technical | – | ||

| Psychosocial | 0.54 | – | |

| Interpersonal | 0.51 | 0.79 | – |

| Assessments of patient observers | |||

| Medical technical | – | ||

| Psychosocial | 0.70 | – | |

| Interpersonal | 0.68 | 0.77 | – |

| Cohort 2000–2001 | |||

| All quality assessments | |||

| Medical technical | – | ||

| Psychosocial | 0.58 | – | |

| Interpersonal | 0.64 | 0.76 | – |

| Assessments of GP observers | |||

| Medical technical | – | ||

| Psychosocial | 0.55 | – | |

| Interpersonal | 0.56 | 0.77 | – |

| Assessments of patient observers | |||

| Medical technical | – | ||

| Psychosocial | 0.62 | – | |

| Interpersonal | 0.71 | 0.76 | – |

Changes in quality assessments over time

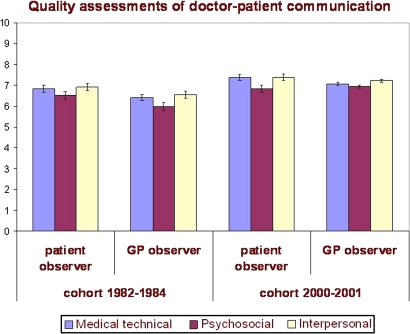

The assessments of the second cohort (2000–2001) were higher than for the first cohort (1982–1984) for the three dimensions (see figure 1). The multilevel regression analyses showed significant effects of cohort in all three dimensions: medical technical quality (B=0.58, Z=5.43, p<0.001), psychosocial quality (B=0.35, Z=2.36, p<0.05) and quality of interpersonal behaviour (B=0.50, Z=3.64, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Means (and 95% CI) of assessments of medical technical quality, psychosocial quality and quality of interpersonal behaviour.

Comparing patient observers' and GP observers' assessments

The figure shows that the assessments of GP observers were somewhat lower than the assessments of patient observers; however, in none of the three dimensions was this difference found to be significant: medical technical quality (B=−0.36, Z=1.89, NS), psychosocial quality (B=−0.19, Z=0.93, NS) and quality of interpersonal behaviour (B=−0.24, Z=1.55, NS).

When examining the variance of the quality assessments, the standard deviations of the assessments by patient observers and GP observers in the second cohort were smaller than in the first cohort on all three dimensions (for patient observers; medical technical quality: F(478, 528)=1.18, p<0.05, psychosocial quality: F 480, 528)=1.20, p<0.05, quality of interpersonal behaviour: F(479, 537)=1.30, p<0.01 and for GP observers; medical technical quality: F(327, 1288)=2.03, p<0.001, psychosocial quality: F(326, 1288)=2.71, p<0.001, quality of interpersonal behaviour: F(327, 1288)=2.26, p<0.001). Furthermore, all standard deviations in the assessments of GP observers were smaller than those with the patient observers in the first cohort (medical technical quality: F(478, 327)=1.83, p<0.001, psychosocial quality: F(480, 326)=1.59, p<0.001, quality of interpersonal behaviour: F(479, 327)=1.64, p<0.001) and second cohort (medical technical quality: F(528, 1288)=3.14, p<0.001, psychosocial quality: F(528, 1288)=3.58, p<0.001, quality of interpersonal behaviour: F(537, 1288)=2.85, p<0.001).

In the model with the assessment of medical technical quality, the intraclass correlation on video level was 14% and on observer level 32%. For psychosocial quality, video level contained 26% and observer level 27% of the variance; for quality of interpersonal behaviour we calculated a variance of 27% on video level and 18% on observer level.

Discussion

Hypertension consultations in general practice in the Netherlands received higher quality assessments by general practitioners and patients on medical technical quality, psychosocial quality and the quality of interpersonal behaviour in 2000–2001 than in the 1980s. The three dimensions of quality were moderately to highly correlated, so there was internal consistency in the quality assessments within consultations. The assessments of interpersonal quality were higher than the assessments on the other two dimensions, which supports the central role of the doctor–patient relationship in the medical interaction between general practitioners and their patients. GP and patient observers agreed on the improved quality of the consultations, but GP observers showed less variation in their assessments than patient observers. There was also less variation in the assessments of the second cohort than with the first cohort, which implies that there is greater consensus on the quality of the more recent consultations.

Standardised care in general practice

Our findings indicate that in this particular sample of videotaped hypertension visits, the shift towards a more task-oriented communication style7 did not jeopardise the individual attention for the patient, since medical technical quality and also psychosocial quality and the quality of interpersonal behaviour received higher quality assessments over time. These results are remarkable because patients and doctors shared fewer concerns and less process-oriented talk (partnership building and directions) in more recent consultations.7 Apparently, these shifts in communication styles do not necessarily lead to a decline in perceived quality of GPs' communication. While this might be expected from the GP observers (the quality measures were highly inter-related, suggesting a certain ‘halo effect’), we had expected that patients would prefer the older videotapes in which the GP was less instrumental. Several studies demonstrate the importance patients attach to affective communication with GPs.31 32 This seemingly contradictory result needs further examination—for example, in qualitative focus groups. Another important finding is the smaller variability in the quality assessments of general practitioners in the later cohort, which can be considered as a sign that professionals are successfully assisted by clinical guidelines to assess the quality of care. There seems to be better consensus between general practitioners on what can be considered a ‘good’ consultation in respect of the more recent consultations.

Tailored approach to doctor–patient communication

In contrast with the GP observer assessments, there was a relatively high variance in the patient observer level, indicating large individual differences between patient observers.

However, this is understandable since patient observers, in particular, base their ratings on experiential knowledge that can differ greatly between patients. Moreover, several studies show that patient preferences vary widely.33 34 Therefore, the high variability between patients calls for a patient-centred and individually tailored approach to doctor–patient communication in general practice.

Strengths and limitations of the study

A strong point of this study is that we examined medical interactions using videotaped real-life general practice consultations with patients with hypertension from two distinct time periods. Thus, the findings refer to actual behaviour, as perceived by uninvolved observers. In addition, the videotaped participants were not aware of the fact that the analyses would focus on hypertension consultations. Video recording is a valid method of examining doctor–patient communication: the influence of the video recorder on participants' behaviour is marginal.35 Moreover, the inclusion of both the professionals' and the patients' perspective enables a comprehensive view on quality of care. The observers were either experienced GPs or experienced patients (patients with hypertension who visit their general practitioner regularly), so they were well able to relate to the videotaped consultations. In addition, we matched the medical condition of the patient observers with the patients in the videotaped consultations. Previous studies show that lay people (experienced patients) can rate videotaped doctor–patient interactions well and provide an added value over ratings given exclusively by professionals or researchers.34 36 37

A possible weakness of the study is that the assessments of the professionals were executed by contemporary peers, while the assessments of patients were performed retrospectively. The GP observers judged the videotaped consultations in the same time period in which the consultations took place. Therefore, the context in which the GP observers rated the consultations changed between the two cohorts. Although identical instructions to the two groups of GP observers was guaranteed because one of the authors (JB) was involved in both previous studies,7 15 we cannot avoid a time- and context-related effect of the GP assessments. In contrast, the patient observers judged videotaped consultations that took place approximately 10 or 30 years ago. The context in which their ratings were conducted did not change between the two cohorts, but was also influenced by current knowledge and experience. Since it can be argued that expectations of what is considered a ‘good’ consultation are also subject to change over time, we cannot automatically assume that quality assessments would have been identical if patient observers had also rated the consultations in the same time period as the recording of the consultations. However, the concurrence of assessments of patient observers and GP observers in their different contexts reinforces our conclusions. Another possible weakness is that the majority of consultations were hypertension repeat visits. A concern with hypertension repeat visits may be that these visits do not sufficiently deal with psychosocial care owing to time constraints or the nature of the problem. However, attention to psychosocial aspects does not have to be time intensive.38 In addition, patients are already familiar with the GP at repeat visits, which might stimulate patients to voice their concerns. Nevertheless, we need to be cautious with the generalisation of our findings.

This study shows that although there is an increased emphasis on task-oriented care in general practice, there is a higher perceived quality of doctor–patient communication in more recent consultations on different dimensions—both medical technical care, and the psychosocial aspects and the doctor–patient relationship. The next step in this line of research is to unravel the factors that determine patients' quality assessments of doctor–patient communication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the GP observers and patient observers who made the assessments. We are grateful to the general practitioners and the patients who participated in the study. We also thank Peter Spreeuwenberg for statistical advice.

Footnotes

To cite: Butalid L, Verhaak PFM, Tromp F, et al. Changes in the quality of doctor–patient communication between 1982 and 2001: an observational study on hypertension care as perceived by patients and general practitioners. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000203. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000203

Funding: This work was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. The previous studies in which the recording of the consultations was performed were financed by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport; the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) and the research fund of the Innovation Fund of Health Insurers (RVVZ).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The studies were carried out according to Dutch privacy legislation. The privacy regulation was approved by the Dutch Data Protection Authority. According to Dutch legislation, approval by a medical ethics committee was not required for these observational studies.

Contributors: LB coordinated the patient observers' assessments, formulated the study questions, discussed core ideas, analysed the data and wrote the paper. PV designed the original study, discussed core ideas and edited the paper. FT coordinated the second cohort GP observers' assessments, and commented on the paper. JB coordinated the first cohort GP observers' assessments, designed the original study, discussed core ideas, and edited the paper. All authors approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Consent for data sharing was not obtained from study participants, but the presented data are anonymised and there is no risk of identification. Access to the dataset is available from the corresponding author (l.butalid@nivel.nl) in STATA format for academic researchers interested in undertaking a formally agreed collaborative research project.

References

- 1.Lain C, Davidoff F. Patient-centered medicine. A professional evolution. JAMA 1996;275:152–68531314 [Google Scholar]

- 2.McWhinney IR. Primary care: core values. Core values in a changing world. BMJ 1998;316:1807–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith R. All changed, changed utterly. British medicine will be transformed by the Bristol case. BMJ 1998;316:1917–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bensing J. Bridging the gap. The separate worlds of evidence-based medicine and patient-centered medicine. Patient Educ Couns 2000;39:17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Brink-Muinen A, Van Dulmen SM, De Haes HC, et al. Has patients' involvement in the decision-making process changed over time? Health Expect 2006;9:333–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bensing JM, Verhaak PFM. Communication in medical encounters. In: Kaptein A, Weinman J, eds. Health Psychology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bensing JM, Tromp F, Van Dulmen S, et al. Shifts in doctor-patient communication between 1986 and 2002: a study of videotaped General Practice consultations with hypertension patients. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:62–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noordman J, Verhaak P, Van Beljouw I, et al. Consulting room computers and their effect on GP-patient communication: comparing two periods of computer use. Fam Pract 2010;27:644–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell SM, Roland MO, Middleton E, et al. Improvements in quality of clinical care in English general practice 1998-2003: longitudinal observational study. BMJ 2005;331:1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid CM, Ryan P, Miles H, et al. Who's really hyperetnsive? Quality control issues in the assessment of blood pressure for randomized trials. Blood Press 2005;14:133–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grol R, Polleman M, Verheij T. De meerjarige beroepsopleiding tot huisarts. II: ‘Structuurplan’ en onderwijsdoelen [The multi-year training for GPs. II: 'Structure' and goals]. Medisch Contact 1986;41:539–44 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramer AW, Düsman H, Tan LH, et al. Effect of extension of postgraduate training in general practice on the acquisition of knowledge of trainees. Fam Pract 2003;20:207–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrat A. Evidence based medicine and shared decision making: the challenge of getting both evidence and preferences in to health care. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:407–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krahn M, Naglie G. The next step in guideline development: incorporating patient preferences. JAMA 2008;300:436–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bensing JM. Doctor-Patient Communication and the Quality of Care: An Observation Study into Affective and Instrumental Behaviour in General Practice [dissertation]. Utrecht: NIVEL, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, et al. ‘Stress’ and coronary heart disease: psychosocial risk factors. Med J Aust 2003;178:272–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill MN, Miller NH, De Geest S. American Society of Hypertension Writing Group Adherence and persistence with taking medication to control high blood pressure. J Am Soc Hypertens 2011;5:56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Bone LR, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intervention to enhance patient-physician partnership, patient adherence and high blood pressure control among ethnic minorities and poor persons: a study protocol NCT00123045. Implement Sci 2009;4:7–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White KL. The Task of Medicine: Dialogue at Wickenburg. Menlo Park: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart M, Roter D, eds. Communicating with Medical Patients. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute NIH, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caron-Flinterman JF, Broerse JEW, Bunders JFG. The experiential knowledge of patients: a new resource for biomedical research? Soc Sci Med 2005;60:2575–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Britten N. Patients' ideas about medicines: a qualitative study in a general practice population. Br J Gen Pract 1994;44:465–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brody DS, Khaliq AM, Thompson TL. Patients' perspectives on the management of emotional distress in primary care settings. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:403–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verhaak PF. Detection of psychologic complaints by general practitioners. Med Care 1988;26:1009–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bensing J. Doctor-patient communication and the quality of care. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:1301–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bensing J, Dronkers J. Instrumental and affective aspects of physician behavior. Med Care 1992;30:283–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van den Brink-Muinen A, Van Dulmen AM, Schellevis FG, et al. Tweede Nationale Studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk: oog voor communicatie: huisarts-patiënt communicatie in Nederland. [The second National Study of Diseases and Actions in General Practice: An Eye for Communication: Doctor-Patient Communication in the Netherlands]. Utrecht: NIVEL, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap [Dutch College of General Practitioners] Huisarts & praktijk: hypertensie. Huisarts en wetenschap [General Practitioner & Practice: Hypertension. General Practitioner and Science]. Utrecht: NHG,1977 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geijer RMM, Burgers JS, Van der Laan JR, et al. NHG–Standaard Hypertensie, tweede herziening. NHG–standaarden voor de huisarts, deel 1 [Clinical Guideline for Hypertension of the Dutch College of General Practitioners, Second Revision. Clinical Guidelines for the Practitioner, Part 1]. Maarssen: Elsevier/Bunge, 1999:187–205 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Fam Pract 1998;15:480–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cape J, McCulloch Y. Patients' reasons for not presenting emotional problems in general practice consultations. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:875–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM. Optimal matches of patient preferences for information, decision-making and interpersonal behaviour: Evidence, models and interventions. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:319–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swenson SL, Zettler P, Lo B. ‘She gave it her best shot right away’: patient experiences of biomedical and patient-centered communication. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:200–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arborelius E, Timpka T. In what way may videotapes be used to get significant information about the patient-physician relationship? Med Teach 1990;12:197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazor KM, Ockene JK, Rogers HJ, et al. The relationship between checklist scores on a communication OSCE and analogue patients' perceptions of communication. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2005;10:37–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moretti F, Van Vliet L, Bensing J, et al. A standardized approach to qualitative content analysis of focus group discussions from different countries. Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:420–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, et al. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol 1999;17:371–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.