Abstract

Background

Reported off-label/unlicensed prescribing rates in children range from 11% to 80%. Research into pharmacokinetic profiles of children's medicines is essential in the creation of more knowledge on the safety and efficacy of medicines in children. This study investigated how often pharmacokinetic data are collected in clinical trials of medicines in children by analysing registered records of clinical trials.

Methods

The registered records of all clinical trials in children that were recruiting on 22 May 2009 were identified on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform using a Clinical Trials in Children search filter. The records of trials in children below 12 years of age, in which the intervention was one or more medicines, were assessed for evidence that pharmacokinetic data would be collected.

Results

Of 1081 eligible trial records, 257 (24%) declared that pharmacokinetic data would be collected. Of these trials, 199 (77%) recruited in Northern America; recruitment in all other regions was below 20%. Trials recruited most often in children over 2 years of age (74%), and least often in newborn infants (32%). Most trials researched medicines in the field of cancer (29%). Trials investigated one-third of the medicines that were indicated as a priority for pharmacokinetic research by the European Medicines Agency.

Conclusions

There is a need for increased knowledge of the pharmacokinetic profiles of children's medicines. The amount of currently ongoing pharmacokinetic research does not seem to address adequately the lack of knowledge in this area. This study sets a baseline for monitoring of future progress on the amount of ongoing pharmacokinetic research in children.

Keywords: Public health, statistics &research methods, pharmacokinetics, clinical trials registration, paediatrics, pharmacology, clinical trial

Article summary

Article focus

The main aim of this study was to assess how many registered records of clinical trials of medicines that were recruiting children and were identifiable on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal contained evidence that pharmacokinetic data would be collected.

Secondary aims were to assess which pharmacokinetic data were collected and what types of trials were reporting pharmacokinetic data.

Key messages

This study quantifies, for the first time, the amount of currently ongoing research into pharmacokinetic profiles of medicines in children.

It shows how much and what kind of pharmacokinetic research is being carried out worldwide as registered at clinical trial registries and analyses the types of trials that perform this research.

It sets a baseline for future studies, to monitor progress in the amount of pharmacokinetic research that is performed in children.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study is one of the first studies of its kind, in that it has created a comprehensive oversight of the amount of ongoing research in one particular research area, by analysing information in registered records of clinical trials. Using information in clinical trial databases as such offers a unique, and currently underused, method for informing future research prioritisation efforts at a policy level (in our case of paediatric off-patent medicines by the European Medicines Agency).

This study is limited by the quality of information in the included registered records. Studying registered records of clinical trials is not the same as studying how clinical trials were in fact conducted. However, in the absence of open access to complete trial protocols we have no other choice than to use the information entered into a trial registry for this type of analysis.

Introduction

Knowledge on the efficacy and safety of medicines for children is still very limited. Off-label (outside the product licence) and unlicensed (without a licence for children) prescription rates in children range from 11% to 80%.1 Only 20–30% of drugs that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in the past were also labelled for use in children.2 Adult dosing cannot be logically extrapolated to paediatric dosing according to weight or age because of different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles in children as compared with adults.3–5 Differences in drug metabolism between children and adults also lead to differences in susceptibility to adverse drug reactions.6 Worryingly, adverse drug reactions have been shown to occur more frequently with off-label prescribed drugs.7 The magnitude of this problem is exemplified by one source which estimates that almost one-quarter of all children in the USA used at least one prescription drug in the last month and that the total number of drugs used per 100 children in the USA over 2004 and 2005 was 338.4.8 To accelerate progress towards improved availability and access to safe child-specific medicines for all children below 12 years of age, the ‘Make medicines child size’ campaign was launched by the WHO in 2007.9

It has been a requirement of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors since 2004 that all clinical trials be prospectively registered in a publicly available clinical trials registry in order to be considered for publication of trial results.10 As of April 2011 the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) offers a single point of access (the ICTRP Search Portal) to data from over 130 000 clinical trials made available by clinical trial registries around the world.11 The importance of high-quality information on clinical trials recruiting children is increasingly being recognised. The Pan African Clinical Trials Registry (a WHO Primary Registry to the ICTRP) has, for example, recently created a child strategy,12 and the European Union has implemented legislation mandating that the EudraCT database of clinical trials ‘should include a European register of clinical trials of medicinal products for paediatric use’.13 To improve access to information on clinical trials in children for healthcare workers, researchers, and patients and their parents, the ICTRP has developed a filter (referred to as the Clinical Trials in Children or CTC filter) on the ICTRP Search Portal which makes it possible to search the portal for clinical trials in children with reasonable accuracy.14

Collecting pharmacokinetic data in paediatric drug trials is fundamental in the development of a larger body of evidence on the safety and efficacy of children's medicines. The aim of this study was to assess how many registered records of clinical trials of medicines that were recruiting children and were identifiable on the ICTRP Search Portal contained evidence that pharmacokinetic data would be collected.

Methods

Data sources

The ICTRP Search Portal imports the WHO Trial Registration Data Set (the minimum amount of trial information that must appear in a register in order for a given trial to be considered fully registered) from registries that meet WHO criteria, including ClinicalTrials.gov.15 As the format of each data item differs across registries, data are currently imported into the portal as text. The ICTRP publishes a hyperlink to the record in the source registry (ie, the registry that provided the data) so users can view additional information, if required. At the time of this study, nine registries provided data to the ICTRP: The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR), the Chinese Clinical Trial Register (ChiCTR), the Clinical Trials Registry—India (CTRI), ClinicalTrials.gov, the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS), the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN), the Netherlands National Trial Register (NTR) and the Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry (SLCTR).

During this study, the CTC filter operated through a search paradigm of over 4000 keywords that were compiled by consulting child-health experts who identified key terms relevant to children and adolescents.14

Study selection

The ICTRP database was searched for all recruiting, interventional clinical trials in children using the CTC filter. The resulting records were scanned manually for eligibility. To be eligible, trial records needed to describe trials that included children below 12 years of age. For trials where inclusion of participants below 12 years was unclear from the record, the record was considered eligible only when an explicit statement was present that the trial was recruiting children, or when the investigated disease was listed as child-specific in the CTC search-filter keyword database. When a trial researched an intervention in pregnant mothers, records were only included when outcomes were defined for the child.

Eligible trials also needed to have at least one arm that involved the evaluation of one or more medicines. Interventions were coded to be medicines or not by using the coding system for intervention types on ClinicalTrials.gov.16 Interventions that were drugs, biologicals or dietary supplements were considered to be medicines. Excluded were records of trials that researched general dietary interventions (as opposed to dietary supplements), vaccines, intravenous fluids (without mentioning of specific substance names), oxygen and nitric or nitrous oxide treatments, transplantations or transfusions, sucrose and glucose water for treatment of pain in newborns, alcohol cleansing of intravenous materials, somatic cell transplants and transfusions, pro- and prebiotics, and surfactant treatments.

Data extraction

The following information was collected manually for all eligible registered records: the age of included participants, country/countries of recruitment, study phase and nature of sponsorship. Geographical regions of the United Nations Statistics Division were used to group countries.17 The age of participants was categorised according to the International Conference on Harmonisation topic E11 age classification of paediatric patients.18

Eligible registered records were searched for the presence or absence of collection of pharmacokinetic data. Pharmacokinetic data were defined as parameters that describe the fate of externally administered substances to humans after administration. Both parameters of the drug and its metabolites were denoted to be pharmacokinetic data (eg, 25(OH)D or 1,25(OH)2D levels were recorded as pharmacokinetic outcomes of vitamin D treatment). Collection of pharmacokinetic data could be mentioned in the outcome entry fields or elsewhere in the record.

We determined whether pharmacokinetics were recorded as a primary or a secondary outcome measure. (If collection of pharmacokinetic data was mentioned outside the outcome fields, it was denoted a secondary outcome measure.) Furthermore, we documented which of the following pharmacokinetic data were studied: absorption, area under the curve of plasma or tissue concentration, autoinduction response, balance, bioavailability, breakdown, clearance, distribution, elimination, excretion, faecal clearance, faecal excretion, lowest concentration, metabolism, peak concentration, plasma half-life (t1/2), plasma or tissue concentration, renal clearance, time to lowest concentration, time to peak concentration, urinary excretion, volume of distribution, or general mentioning of pharmacokinetic data collection or a pharmacokinetic study design. Use of a population pharmacokinetic design and additional general mentioning of pharmacodynamic data collection or the use of a pharmacodynamic study design were denoted.

The primary health condition or problem studied and the drug, biological or dietary supplement that was under investigation were denoted for trials that reported collection of pharmacokinetic data. The primary health condition or problem studied was categorised according to WHO Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases chapters.19 For drugs, biologicals and dietary supplements, we adhered to the names for the interventions as denoted in the registered record, except when proprietary names were used, which we converted to non-proprietary names. When there were multiple medicines described, but there was one main intervention, and the record lacked specification for which medicines pharmacokinetics would be determined, it was assumed that pharmacokinetics would be determined for the main intervention. The drugs, biologicals and dietary supplements that were found were compared with the medicines for which there was a priority need for pharmacokinetic data, according to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) revised priority list for studies into off-patent paediatric medicinal products from 2008, which was the most recent version at the time of this study.20 Furthermore, we analysed the EMA 2009 and 2010 priority lists to see whether medicines from the 2008 list endured to be priorities for pharmacokinetic investigation. Lastly, to investigate whether there were any trials that studied EMA priority medicines without collecting pharmacokinetic data, we searched the scientific and public titles of all studies in our sample for mention of the EMA priority medicines.

All records were scanned for eligibility by RFV who then, in case of inclusion, extracted and coded the data. During eligibility assessment and data extraction, trial records for which data were ambiguous were further assessed by DG. Conflicts were resolved by mutual agreement.

SPSS V. 16.0.1 was used for descriptive analyses of the data.

Results

The ICTRP Search Portal was searched using the CTC filter on 22 May 2009 resulting in the identification of 3051 records of interventional clinical trials in children, of which 1081 were investigating one or more medicines (ie, the intervention was a drug, biological or dietary supplement) and mentioned inclusion of children below 12 years of age. Two hundred and fifty-seven (24%) of these records reported that pharmacokinetic data would be collected. The medicines that were investigated by the corresponding trials were drugs or biologicals in 209 records (81%) and dietary supplements in 48 records (19%).

The 1081 records of children's trials reported recruitment of participants in 92 countries; the records that reported collection of pharmacokinetic data recruited in 48 countries. Of the 257 records that reported collection of pharmacokinetic data, 199 records (77%) reported recruitment in Northern America; recruitment in all other regions was below 20% (table 1). Among the 824 records of trials without pharmacokinetic data collection, Northern America was also the most frequent geographical region of recruitment, but less so (57%).

Table 1.

Age groups of study participants, geographical regions of recruitment, study phase and sponsorship of trial records included in the study

| Records from trials that reported collection of pharmacokinetic data (N=257) |

Records from trials that did not report collection of pharmacokinetic data (N=824) |

Total | Percentage of total reporting collection of pharmacokinetic data per age group, region, phase or sponsor | |||

| No of records | Percentage of N=257 | No of records | Percentage of N=824 | |||

| Age* | ||||||

| Newborn infants (0 to 27 days) | 81 | 32 | 226 | 27 | 307 | 26 |

| Infants and toddlers (28 days to 23 months) | 126 | 49 | 371 | 45 | 497 | 25 |

| Children between the ages of 2 and 11 years | 190 | 74 | 680 | 83 | 870 | 22 |

| Not indicated | 3 | 1 | 19 | 2 | 22 | – |

| Geographical region* | ||||||

| Africa | 16 | 6 | 44 | 5 | 60 | 27 |

| Asia | 26 | 10 | 94 | 11 | 120 | 22 |

| Europe | 50 | 19 | 217 | 26 | 267 | 19 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 25 | 10 | 61 | 7 | 86 | 29 |

| Northern America | 199 | 77 | 469 | 57 | 668 | 30 |

| Oceania | 13 | 5 | 83 | 10 | 96 | 14 |

| Not specified | 12 | 5 | 35 | 4 | 47 | – |

| Phase | ||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 1 | 69 | 27 | 43 | 5 | 112 | 62 |

| 1 and 2 | 31 | 12 | 23 | 3 | 54 | 57 |

| 2 | 45 | 18 | 149 | 18 | 194 | 23 |

| 2 and 3 | 11 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 43 | 26 |

| 3 | 38 | 15 | 215 | 26 | 253 | 15 |

| 3 and 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 4 | 15 | 6 | 146 | 18 | 161 | 9 |

| Not indicated | 48 | 19 | 209 | 25 | 257 | – |

| Sponsorship | ||||||

| Collaborative research groups | 25 | 10 | 80 | 10 | 105 | 24 |

| Federal | 39 | 15 | 84 | 10 | 123 | 32 |

| Industry | 67 | 26 | 114 | 14 | 181 | 37 |

| University or hospital | 121 | 47 | 502 | 61 | 623 | 19 |

| Other† | 5 | 2 | 43 | 5 | 48 | 10 |

| Not indicated | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | – |

| Total | 257 | 824 | 1081 | |||

Percentages for geographical regions and age groups do not add up to 100% because records regularly pertain to trials recruiting in multiple regions, or recruiting in multiple age groups.

Other sponsorship included foundations, contract research organisations, research centres and individuals.

Looking more closely at the age of participants being recruited in trials that reported collection of pharmacokinetic data, 81 records (32%) involved preterm or term newborn infants (0 to 27 days), 126 records (49%) infants and toddlers (28 days to 23 months) and 190 records (74%) children between the ages of 2 and 11 years.

Mention of pharmacokinetic data collection was most frequent in records of trials that were Phase 1 (62%) or Phase 1 and 2 (57%). Thirty-nine per cent of all trials that reported pharmacokinetic data collection were Phase 1 or Phase 1 and 2, and 43% were Phase 2 to 4 (in 19% of records, the study phase was not provided).

Almost half of the trials that were reported to collect pharmacokinetic data were sponsored by a university or a hospital. Although there were fewer federal-sponsored (15%) and industry-sponsored (26%) trials performing research into medicines in children under 12 years, these trials were more likely to collect pharmacokinetic data (32% and 37% respectively) than university- or hospital-sponsored studies (19%).

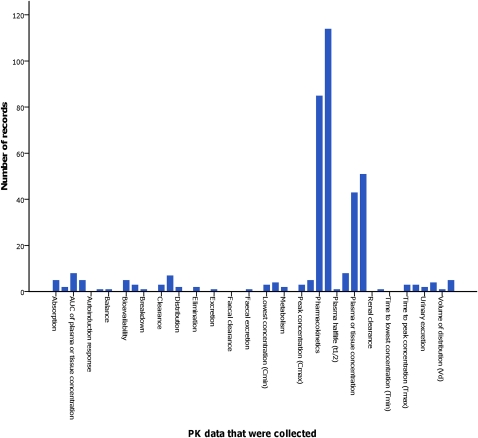

Of the 257 records that reported collection of pharmacokinetic data, 56 records (22%) mentioned only the measuring of serum or tissue concentrations and did not mention a pharmacokinetic study design, or any of the other pharmacokinetic parameters (34 of these 56 records (61%) were of trials that investigated dietary supplements). Figure 1 shows in more detail which pharmacokinetic data were reported to be collected in records. One hundred and twenty-four records (48%) reported pharmacokinetic data as a primary outcome, and 163 (63%) reported pharmacokinetic data as a secondary outcome (the overlap is due to the mention of pharmacokinetic data as both a primary and a secondary outcome measure in 30 records). Eleven records (4%) mentioned use of a population pharmacokinetic design. Fifty-two records (20%) mentioned pharmacodynamic data collection or the use of a pharmacodynamic study design in addition to pharmacokinetic data collection (out of the 824 records that did not report pharmacokinetic data collection, 12 records mentioned collection of pharmacodynamic data).

Figure 1.

Collected pharmacokinetic (PK) data in paediatric drug trials. Every first bar represents which pharmacokinetic data were reported as a primary outcome; every second bar those that were reported as a secondary outcome. AUC, area under the curve.

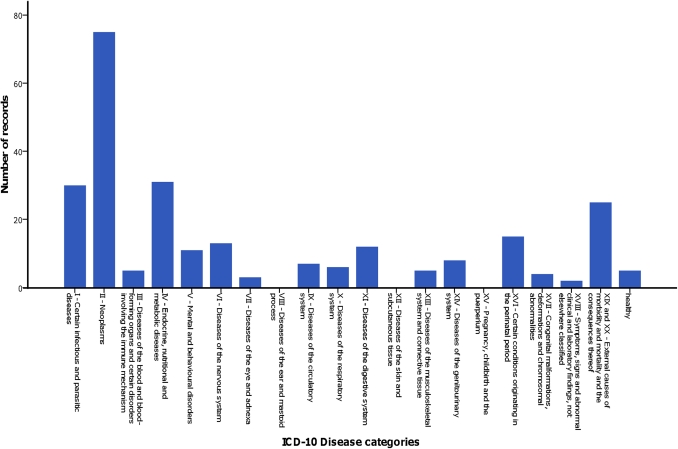

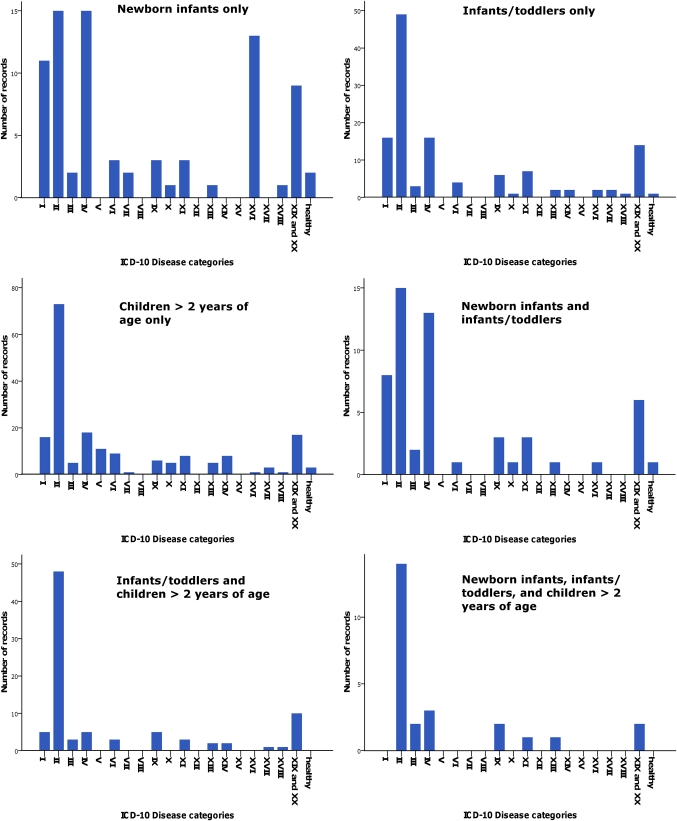

The primary health condition or problem studied in trials that collected pharmacokinetic data was most often cancer (29%) (figure 2). The distribution of health conditions or problems studied differed per age group, with less of a propensity for cancer research among the group of newborn infants (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Investigated health conditions or problems in trials that collected pharmacokinetic data. ICD-10, Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases.

Figure 3.

Investigated health conditions or problems per age group. The graph on the top left displays the distribution of health conditions or problems studied in trials that recruited only newborn infants; the top-right graph displays this information for trials that recruited only infants/toddlers; the middle left graph for trials that recruited only children >2 years of age; the middle right graph for trials that recruited newborn infants and infants/toddlers; the lower left graph for trials that recruited infants/toddlers and children >2 years of age; and the lower right graph for trials that recruited newborn infants, infants/toddlers and children >2 years of age. ICD-10, Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases.

A detailed oversight of the medicines that were investigated by trials that reported collection of pharmacokinetic data can be found in Web Only File 1. Of the 28 medicines on the EMA revised priority list for studies into off-patent paediatric medicinal products from 2008 for which collection of pharmacokinetic data was indicated to be a priority, we found nine medicines (32%) to be investigated in trials identified in our search (table 2).

Table 2.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) 2008 priorities for pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis

| Name of medicine | Notes | Investigated in trial records identified on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal? | Still in 2009 EMA priorities? | Still in 2010 EMA priorities? | Medicine investigated in trials without collection of PK data? | In how many trial records? |

| 6-Mercaptopurine | In infants | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Actinomycin | Below the age of 6 years | Yes | No | No | ||

| Asparaginase | In infants | Yes | No | No | ||

| Baclofen | Yes | No | No | |||

| Bumetanide | No | No | No | No | ||

| Carboplatin | Below the age of 3 years | No | No | No | Yes | 10 |

| Cladribine | No | No | No | No | ||

| Clindamycin | No | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Clonidine | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | Data on PK of metabolites | Yes, including metabolites | No | No | ||

| Cytarabine | In infants | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Daunorubicin | In infants | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Ethosuximide | No | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Foscarnet | No | No | No | No | ||

| Glibenclamide | Above 6 years and adolescent | No | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | No | No | No | No | ||

| Ibuprofen | Parenteral formulation | No* | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 |

| Itraconazole | No | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Levamisole | No | No | No | No | ||

| Meropenem | Below 3 months of age | No | No | No | No | |

| Metformin | In children above 6 years with DM II and in small-for-gestational-age children with precocious/early/rapidly progressing puberty | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 |

| Midazolam | No | No | No | Yes | 4 | |

| Milrinone | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 | |

| Oxybutynin | No | No | No | No | ||

| Propranolol | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 | |

| Temozolomide | In children particularly below the age of 3 years | Yes | No | No | ||

| Topotecan | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Unfractionated heparin | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 | |

| Percentage ‘Yes’ | 9/28=32% | 14/28=50% | 12/28=43% | 8/19=42% |

This table shows which of the medicines that were identified as a priority for PK evaluation by the EMA in 2008 were found to collect PK data in our study sample. We also assessed whether these medicines were still present in the EMA 2009 and 2010 priority lists. Lastly, we searched titles of all 1081 trial records in our sample to assess for which EMA priority medicines trials were conducted without PK data collection (or it was not denoted in the record).

One trial investigated ibuprofen pharmacokinetics, but in oral formulation.

DM II, Diabetes mellitus type II.

Of the 28 medicines that were EMA priorities in 2008, 14 (50%) were still a priority in 2009 and 12 still in 2010 (43%). Of the nine medicines for which we found pharmacokinetic data collection, two were still a priority in 2010 (22%). Of the 19 medicines for which we did not find pharmacokinetic data collection, 10 were still a priority in 2010 (53%).

Academic and public titles of the 1081 records in the sample were searched for the names of the 19 medicines for which we did not find pharmacokinetic data collection in any record. Eight (42%) of these medicines were identified in 29 trial records as an intervention.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the global activity of collection of pharmacokinetic data in clinical trials in children. It assessed all paediatric trials that were recruiting on 22 May 2009, as registered at clinical trial registries that are a part of the ICTRP registry network. Of 1081 records of trials researching medicines in children, one-quarter reported that they would be collecting pharmacokinetic data. So, is this a lot or a little? In view of the current paucity of knowledge on safety and efficacy of children's medicines, the degree to which this knowledge is in arrears as compared with our understanding of adult medication, and the widespread prescribing of medicines to children, we would argue that it is not enough.

The fact that only one-fifth of the records that mentioned collection of pharmacokinetic data also mentioned studying pharmacodynamics adds to this conclusion. Additionally, our analysis of the types of trials researching pharmacokinetics shows that there might be significant pharmacokinetic research gaps in terms of geographical area, studied diseases and age categories. Over 75% of all studies recruited participants in Northern America, while recruitment in all other geographical regions was below 20%. This unequal distribution appears to exist for all paediatric drug trials, but especially for studies collecting pharmacokinetic data. Given the existence of interethnic differences in pharmacological effects on the body21 and that many diseases are not prevalent in Northern America, this gap is a reason for concern. Similarly, the distribution of pharmacokinetic research across different disease categories suggests that the lack of knowledge of pharmacokinetics in children is only marginally addressed in some areas. Previous studies have shown that paediatric research in general often does not address priority research areas.22 23 Finally, although knowledge on pharmacokinetic profiles in children is at an inadequate level for all age groups, least is known about pharmacokinetics in the youngest age group of neonates.24 25 This study shows that this age group, worryingly, is also the least likely to be studied.

In addition, trials in our study sample were found to collect pharmacokinetic data only for one-third of the medicines on the EMA priority list for studies into off-patent paediatric medicinal products.20 Although our study investigated a cross-sectional sample of recruiting paediatric trials at one moment in time, one-third seems to be a low percentage. Also taking into consideration that a considerable amount of medicines endured to be priorities for research over several years, and that there were ongoing clinical trials in which the pharmacokinetic properties of these medicines could potentially have been studied, this might suggest that more research on pharmacokinetic profiles in children is not only necessary but also achievable.

The paediatric research community has much to gain from the inclusive database of clinical trials in children that the ICTRP search portal provides through its Clinical Trials in Children search filter.26 Clinical trials registration allows for doctors and patients and their parents to inform themselves more adequately about trials open to recruitment.27 It is likely to promote collaboration among researchers, by facilitating knowledge transfer on currently ongoing research, thus also preventing duplication of research.28 Furthermore, it has the potential to contribute to establishing more reliable research evidence by aiding in the prevention of selective reporting and publication bias.27 29 Although the ethical and legal pressure to adequately report the results of clinical trials is increasing,30 selective reporting and publication bias are still important problems.31 32 If all trials (and their outcomes) are registered before the start of the trial, researchers who withhold publication of trial results or the original outcomes because of negative results can be held accountable.30 33 34 Finally, clinical trials registration facilitates priority setting in paediatric research, identifying gaps between burden of disease and research efforts in different therapeutic areas.35 This study confirms that analysis of clinical trials identified in the ICTRP database can be a powerful tool to comprehensively assess the amount of currently ongoing research in a particular research area.

The need for improved availability of and access to safe child-size medicines has received growing attention in recent years.1 36 WHO addresses this issue through its ‘make medicines child size’ campaign.9 Other initiatives that promote trials on medicines in children include US and EU legislation.13 37 While these legislative measures are a positive development and have resulted in an increased number of trials being conducted in the paediatric population,37 38 they have not been free from critique.23 39 Given how crucial pharmacokinetic research is in the creation of more knowledge on the safety and efficacy of medicines in children and the concerns that the present study raises on the amount of such research currently being conducted, it is of great importance that the collection of pharmacokinetic data in clinical trials in children continues to be monitored in the future. The Clinical Trials in Children search filter of the ICTRP offers a platform to do so.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to G Karam for his help in attaining a random sample of registered records from the ICTRP database, to A Ridge for her help in designing the study, and to S Hill for her help in designing the study and reviewing early drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

To cite: Viergever RF, Rademaker CMA, Ghersi D. Pharmacokinetic research in children: an analysis of registered records of clinical trials. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000221. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000221

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not for profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Contributions: RFV and DG designed the study; RFV collected the data; RFV, DG and CMAR analysed and interpreted the data; RFV wrote the first draft of the paper; CMAR and DG contributed to the writing of the paper; all agree with the manuscript's results and conclusions.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Dataset available from the corresponding author at roderik.viergever@lshtm.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Pandolfini C, Bonati M. A literature review on off-label drug use in children. Eur J Pediatr 2005;164:552–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meadows M. Drug research and children. FDA Consum 2003;37:12–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginsberg G, Hattis D, Sonawane B, et al. Evaluation of child/adult pharmacokinetic differences from a database derived from the therapeutic drug literature. Toxicol Sci 2002;66:185–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, et al. Developmental pharmacology—drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1157–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokoi T. Essentials for starting a pediatric clinical study (1): Pharmacokinetics in children. J Toxicol Sci 2009;34(Suppl 2):SP307–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson TN. The development of drug metabolising enzymes and their influence on the susceptibility to adverse drug reactions in children. Toxicology 2003;192:37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Impicciatore P, Mohn A, Chiarelli F, et al. Adverse drug reactions to off-label drugs on a paediatric ward: An Italian prospective study. Paediatr Perinat Dr Ther 2002;5:19–24 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health, United States, 2009: With Special Feature on Medical Technology. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Essential Medicines for Children, Make Medicines Child Size. http://www.who.int/childmedicines/en/index.html (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 10.Clinical Trial Registration: A statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. http://www.icmje.org/clin_trial.pdf (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 11.WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). http://www.who.int/ictrp (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 12.Baleta A. African trials registry launches child strategy. Lancet 2010;375:1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and the Council: on medicinal products for paediatric use (L 378).

- 14.WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), Clinical Trials in Children. http://www.who.int/ictrp/child/search/en/index.html (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 15.WHO Trial Registration Data Set (TRDS). http://www.who.int/ictrp/network/trds/en/index.html (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 16.Protocol Data Element Definitions (DRAFT). http://prsinfo.clinicaltrials.gov/definitions.html (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 17.Composition of Macro Geographical (Continental) Regions, Geographical Sub-regions, and Selected Economic and Other Groupings. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 18.ICH Topic E 11 Clinical Investigation of Medicinal Products in the Paediatric Population. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002926.pdf (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 19.International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/ (accessed 15 Jun 2011).

- 20.Revised Priority List for Studies into Off-Patent Paediatric Medicinal Products. London: European Medicines Agency, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie HG, Kim RB, Wood AJ, et al. Molecular basis of ethnic differences in drug disposition and response. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2001;41:815–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandolfini C, Bonati M. Something is moving in European drug research for children, but a more focused effort concerning all therapeutic needs is necessary. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boots I, Sukhai RN, Klein RH, et al. Stimulation programs for pediatric drug research—do children really benefit? Eur J Pediatr 2007;166:849–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conroy S, McIntyre J. The use of unlicensed and off-label medicines in the neonate. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2005;10:115–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conroy S, McIntyre J, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off label drug use in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1999;80:F142–4; discussion F144–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandolfini C, Bonati M, Sammons HM. Registration of trials in children: update of current international initiatives. Arch Dis Child 2009;94:717–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antes G. Registering clinical trials is necessary for ethical, scientific and economic reasons. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antes G, Dickersin K. Trial registration to prevent duplicate publication. JAMA 2004;291:2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viergever RF, Ghersi D. The quality of registration of clinical trials. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e14701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghersi D, Clarke M, Berlin J, et al. Reporting the findings of clinical trials: a discussion paper. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:492–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scherer RW, Langenberg P, von Elm E. Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):MR000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathieu S, Boutron I, Moher D, et al. Comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2009;302:977–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Hines EM, et al. Trial publication after registration in ClinicalTrials.Gov: a cross-sectional analysis. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandolfini C, Bonati M, Rossi V, et al. The DEC-net European register of paediatric drug therapy trials: contents and context. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008;64:611–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saint-Raymond A, Seigneuret N. Medicines for children: time for Europe to act. Paediatr Perinat Dr Ther 2005;6:142–6 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benjamin DK, Jr, Smith PB, Murphy MD, et al. Peer-reviewed publication of clinical trials completed for pediatric exclusivity. JAMA 2006;296:1266–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocchi F, Paolucci P, Ceci A, et al. The European paediatric legislation: benefits and perspectives. Ital J Pediatr 2010;36:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Permanand G, Mossialos E, McKee M. The EU's new paediatric medicines legislation: serving children's needs? Arch Dis Child 2007;92:808–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.