Abstract

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of citalopram for major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults, in a systematic review of all published, randomised, double-blind studies comparing it with a placebo.

Data sources

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, PsychINFO and Embase.

Study selection

Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of citalopram in adults with MDD were included. Studies with medically ill or treatment resistant subjects were excluded, as were studies of relapse prevention. Remission of MDD was defined as a primary outcome, and response or change from baseline scores were defined as secondary.

Data extraction

Remission, response and symptom improvement scores on the Hamilton Depression Scale, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale and Clinical Global Impressions-Severity scales were extracted. A random-effects meta-analysis was carried out on the response rates and symptom improvement scores. Included studies were examined for the presence of bias and small study effects.

Results

Eight studies (n=2025) met the inclusion criteria. Two studies provided data on remission, but only one of these showed a significant difference between citalopram and placebo (RR=1.59, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.31). Meta-analysis of response rates in five studies (n=1010) revealed significant superiority of citalopram (RR=1.42, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.73). Meta-analysis of change from baseline scores in five studies (n=1541) gave a standardised mean difference (Hedges' g) of −0.27 (95% CI −0.38 to to −0.16), showing a reduction in MDD symptoms to be significant for citalopram relative to placebo. There was no evidence of any significant small study effects. The overall quality of reporting was poor, with insufficient information on the methodology or outcomes. Seven studies received industry sponsorship.

Conclusions

Data concerning remission rates for citalopram, relative to placebo, are inconclusive. Response rates and symptom reduction scores in citalopram-treated patients with MDD are significantly better relative to placebo treatment, according to a meta-analysis of published reports. Evaluation of unpublished data is necessary to assess more definitively the effectiveness of citalopram for MDD.

Article summary

Article focus

Systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomised double-blind studies comparing citalopram with placebo in adults with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Evaluation of the quality of published studies and the risk of bias.

Key messages

Data on remission rates for citalopram in MDD, relative to placebo, are inconclusive

Response rates and symptom improvement scores are significantly better in citalopram-treated patients than in those taking placebo.

The quality of reporting in published studies is poor.

Further evaluation of citalopram is necessary, incorporating unpublished research.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This review is based on a thorough search for published placebo-controlled studies of citalopram for adults with MDD, using a broad search strategy. In a departure from previously published reviews, this study assesses the risk of bias and includes remission as a primary outcome.

This study would have been enhanced if the missing data were available for a more complete analysis, and unpublished studies satisfying inclusion criteria were incorporated into this review.

This review was carried out by a single author.

Introduction

Citalopram is a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor antidepressant, commonly used in the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). It is often recommended as a first-line treatment for this condition. This recommendation, however, depends on the quality of studies evaluating this drug, and measures of effectiveness utilised. These issues have not been adequately addressed in previous reviews.1 2

A re-examination of the role of citalopram in the treatment of MDD is therefore necessary, taking into account the quality of studies, risk of bias and different measures of effectiveness. Remission of MDD is the most clinically relevant measure of effectiveness that should be sought when evaluating citalopram for MDD.3–5 The emphasis on remission when evaluating effectiveness can be contrasted with earlier reviews of citalopram, focusing on symptom improvement or response as the main measure of outcome. Filling this gap in the literature, I systematically reviewed all published randomised, placebo-controlled studies of citalopram in adults with MDD. I examined the quality of published studies and the risk of bias, setting remission of MDD as the primary measure of effectiveness in this review.

Methods

Selection criteria

I selected published, randomised, double-blind studies comparing citalopram with placebo among adult participants over the age of 18, who were diagnosed as having MDD using DSM-III,6 DSM-IIIR,7 DSM-IV8 ICD-99 or ICD-10.10 No upper age limit for study participants was set. Studies with a third comparator (eg, another antidepressant) were included, if a direct comparison between citalopram and placebo treatments was possible. Studies involving patients with severe medical illness, other psychiatric disorder or substance abuse were excluded from this review. Studies of MDD that focused on relapse prevention, treatment augmentation or treatment-resistant cases were also excluded, as these studies would have introduced additional heterogeneity into this evaluation.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Remission of MDD. Remission was defined as: a score of <8 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D)11; <9 on longer versions of HAM-D; <12 on the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS);12 or ‘not ill or borderline mentally ill’ on the Clinical Global Impression—Severity (CGI-S) scale.13 These cut-off points provide a consistent definition of ‘remission.’14 15

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were as follows: (a) response of MDD. Response was defined as a reduction of at least 50% on the HAM-D or MADRS scales; or ‘much or very much improved’ on the CGI-I (CGI-Improvement) scale. HAM-D, MADRS and CGI-I have a similar sensitivity to change in depression symptom ratings;16 (b) any reduction in the severity of depression, measured as a reduction in scores relative to baseline values (change from baseline), on the HAM-D, MADRS or CGI scales.

Search methods

I carried out an electronic search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline (from 1950), PsychINFO (from 1967) and EMBASE (from 1980) up to February 2011. Articles with ‘citalopram,’ ‘placebo’ and ‘major or severe depression’ as keywords or exploded MeSH terms, were searched by combining (exp citalopram/OR citalopram.mp) AND (exp placebo/OR placebo*.mp) AND (exp depressive disorder/OR (depress* adj2 (major* or severe*)).mp). The term ‘placebos’ was used as a MeSH heading in the Medline, Cochrane and EMBASE database searches, and ‘major depression’ was used as a MeSH heading in the PsychINFO search. No limits were set for these searches, apart from the EMBASE search, which was limited to the adult population because of the large number of ineligible studies produced by the unrestricted search.

I examined the abstracts of all identified studies, selecting randomised double-blind studies of citalopram in patients with major depressive disorder. Reference lists of review articles and other studies of citalopram were also searched for publications satisfying the inclusion criteria. I then obtained full text copies of these articles and excluded those that: lacked a placebo control group; involved children, adolescents, medically ill or treatment resistant population; or were studies of relapse prevention or of patients with another psychiatric illness.

Data collection

I extracted data into an electronic form with sections for each study describing the methods used, study participants, interventions and measured outcomes, as well as sections for bias evaluation. I reviewed each paper on at least two occasions, to check for accuracy of selection and data extraction, over a 3-month period.

Data on the characteristics of study participants were entered into a table, recording the age and sex of participants, sample sizes in the citalopram and placebo treatment groups, medication doses, drop-out rates and treatment duration. The number of subjects randomised and the number included in outcome evaluation were extracted from each study where possible. I recorded baseline measures of symptom severity and the treatment setting for each study.

I tabulated the proportions of patients who achieved response or remission in the citalopram and placebo arms of selected studies. I included the definitions of ‘response’ and ‘remission’ terms used and extracted the change from baseline measures on the HAM-D, MADRS or CGI depression scales.

Data analysis

Risk of bias was evaluated in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,17 using the following parameters: adequacy of sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; and selective outcome reporting. Small study effects were investigated using a funnel plot. A meta-analysis of response rates was performed to calculate an overall RR of a response to citalopram, compared with placebo, in a random-effects model, using Stata V.9.2.

I carried out a meta-analysis of the change-from-baseline scores on the 17, 21 and 24-item HAM-D scales for participants included in outcome evaluation. I applied a random effects model to calculate Hedges' g for standardised mean differences between citalopram and placebo groups. Standard deviations (SD) were computed from the p values, taken at the upper limit and converted into a t-statistic. I used the formula SD=SE/√(1/Ne+1/Nc), where SE=difference in means of the two change from baseline scores divided by the t-statistic, and Ne and Nc are the sample sizes in the experimental and control groups respectively. I multiplied the result by −1 to convert a measure of symptom reduction into an improvement score.

Results

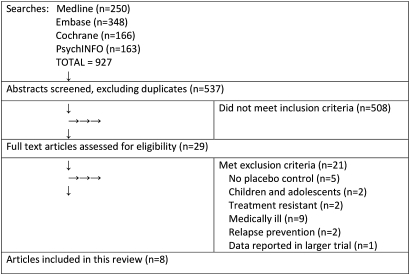

A search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials using the above search terms produced 31 unique articles, Medline 244, PsychINFO 60 and EMBASE 202, giving a total of 537 articles, after removing duplicates. The selection process is described in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of the article selection process.

I inspected the abstracts from the above searches and selected 29 studies for possible inclusion. After examining full text copies of these studies, I compiled a final list of eight studies18–25 that satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Excluded studies lacked a placebo control,26–30 focused on relapse prevention31 32 or were studies of children,33 34 medically ill35–43 or treatment-resistant subjects.44 45 The study by Montgomery et al46 was excluded, as the data in this study were reported in a larger trial by Lepola et al.22

Characteristics of included studies

The combined sample from eight studies consisted of 1237 subjects in the citalopram group and 788 in the placebo group (total=2025). The studies were brief, 2 to 8 weeks in duration, apart from one study,25 which was 24 weeks in length. The mean age of participants was 42 years, with the age ranging between 18 and 74 years. Females constituted two-thirds of the sample in most studies, and the dose of citalopram ranged from 10 to 80 mg a day. One study20 had only 16 participants. All patients recruited in these studies were diagnosed as having MDD using the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III, III-R or IV. Most participants were recruited in outpatient settings. All studies, except for Gastpar 2006, received industry sponsorship.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias in included studies is summarised in table 1. Most studies provided insufficient information to determine whether the random sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors were adequate. Selective reporting of outcome data was evident in all studies, as easily extractable summary statistics such as remission and response rates were often omitted from publication, or data were presented in a form that could not be incorporated into a meta-analysis. Most studies reported blinding of participants and intention-to-treat analyses, using the last-observation-carried-forward approach.

Table 1.

Risk of bias in included studies

| Study | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blind participants and personnel | Blind outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting |

| Burke et al18 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Feighner and Overo19 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Frank et al20 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Gastpar et al21 | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Lepola et al22 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Mendels et al23 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High |

| Montgomery et al24 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High | High |

| Stahl25 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

Baseline characteristics of subjects

Hamilton Depression Scale

Five studies provided mean baseline HAM-D scores.18 19 21 23 25 The patients in these studies had mean baseline HAM-D scores above 17, showing that they were moderately to severely depressed.

Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale

Baseline mean MADRS scores were provided in four studies.18 19 22 25 The mean MADRS scores in these studies were above 22, indicating that patients were moderately (scores between 22 and 29) to severely (scores of 30 or above) depressed.

Clinical Global Impressions-Severity

All studies, except for those of Frank et al20 and Montgomery et al24 provided mean baseline CGI-S scores. Average baseline scores in these study populations were above 4, indicating a moderate level of illness severity. In the study by Gastpar et al,21 more than 92% of patients were assessed as moderately, markedly or severely depressed.

Outcomes

Remission

Two of the eight studies reported remission rates. Stahl25 reported a 45% remission rate in the citalopram group, and 28% remission rate in the placebo group at the end of a 24-week trial (RR=1.59, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.31), with remission defined as a score of <8 on HAMD-17. Lepola et al22 reported a remission rate of 42.8% in the citalopram group, with remission defined as a score of <12 on MADRS, but this rate was not significantly different from placebo. This evaluation was based on observed cases only, and no comparable data for the placebo group were provided. No meta-analyses of this small and incomplete dataset of only two studies were carried out, given the risk of producing an unreliable result.

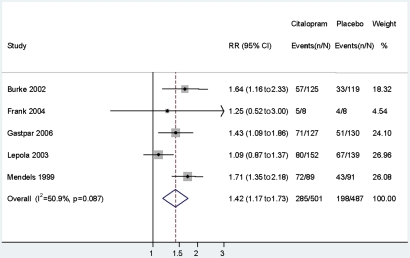

Response rates

Five studies (n=1010) reported response rates, and these were included in the meta-analysis (figure 2). Overall RR for symptom response with citalopram, relative to placebo, was 1.42 (95% CI 1.17 to 1.73), indicating that the response of MDD in citalopram-treated subjects was 42% more likely than in those taking placebo. There was no significant heterogeneity between studies (I2=50.9%, p=0.087). The study by Gastpar et al21 was considered suitable for inclusion in this meta-analysis, despite it using a mixed definition of response—50% improvement or a final score of <10 on the HAM-D.

Figure 2.

Random effects meta-analysis of symptom responses for citalopram and placebo.

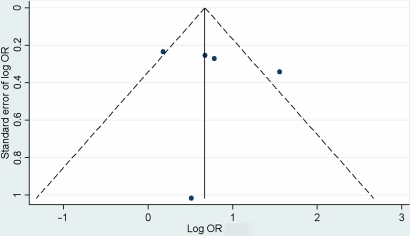

A funnel plot based on the ORs of response rates in these five studies did not reveal any significant small study effects (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of symptom response odds ratios for citalopram and placebo.

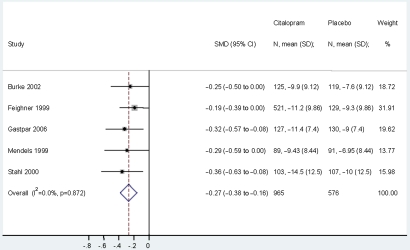

Change from baseline

Five studies, with a total of 1541 subjects, were included in the meta-analysis of change from baseline scores (figure 4). The study by Lepola et al was excluded, as it provided no information for calculating standard deviations, and the studies by Frank et al and Montgomery et al did not report the change from baseline measures for their subjects.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of standardised mean differences (SMD) in change from baseline HAM-D comparing citalopram and placebo.

Hedges' g for the standardised mean difference in the change from baseline scores, comparing citalopram with the placebo group, was −0.27 (95% CI −0.38 to −0.16), which converted to a small but significant improvement score of 0.27. This result indicates that the improvement in the HAM-D scores of subjects treated with citalopram was 0.27 standard deviations better than the improvement in those treated with placebo. There was no significant heterogeneity in the change from baseline HAM-D measures (I2=0%; p=0.872) in the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Two studies provided data on remission rates for citalopram relative to placebo: the difference in remission rates was statistically significant in one study, but not the other. It is therefore not possible to draw definite conclusions regarding this outcome on the basis of the published data, and a further evaluation is required, incorporating unpublished results.

Response rates and change from baseline scores for citalopram, relative to placebo, were statistically significant in these meta-analyses, each one based on a subset of five studies. No significant heterogeneity between these studies was detected. These data provide support for the use of citalopram in MDD, at least in the first 8 weeks of treatment.

Small study effects were not evident in this review, as there was no marked asymmetry on the visual inspection of the funnel plot. However, a formal test of asymmetry was not performed, given the small sample of five studies in this analysis. Publication bias is one potential source of plot asymmetry, not evident here, although this should be more fully assessed after obtaining unpublished research.

The quality of reporting in the reviewed studies was generally poor, with insufficient data to reach conclusions regarding the adequacy of randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of assessors. Most studies omitted data on the remission rates, and none of the studies reported a full set of outcome variables in a way that can be incorporated in a meta-analysis. Inadequate reporting and industry sponsorship of these studies raise the possibility of bias and carry a risk for the validity of this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

My estimation of the standardised mean difference for the change from baseline scores is similar to Hedges' g of 0.31 calculated by Turner on the basis of published studies.47 Importantly, Turner revised the estimation of citalopram's effectiveness to 0.01 after including unpublished results. My conclusions regarding the effect of citalopram on the response and symptom improvement in MDD are consistent with the earlier reviews of this drug.1 48–50 Those reviews, however, have not examined the risk of bias in published studies, or the effect of citalopram on remission of MDD. Remission is an important outcome in clinical practice,4 5 and my study highlights the limited data on this outcome in published research.

Limitations

This systematic review is limited to published studies. Its results are subject to a review of unpublished research and outcome data that are missing from published reports. Nevertheless, this review may serve as a useful summary of published data, highlighting the risk of bias and the paucity of published research into the effect of citalopram on remission of MDD.

This review has been undertaken by a single reviewer. While a single reviewer may be able to select and extract unambiguous data, additional reviewers can help reach consensus regarding areas of ambiguity in published reports. That consensus, however, should not replace missing or ambiguous data, or substitute the importance of adequate reporting that is necessary for a systematic review.

Conclusion

The reviewed published studies show that citalopram has a statistically significant advantage over placebo with respect to symptom improvement and response rates in adults with MDD. Its role in symptom remission is less clear, given the contradictory findings of the two studies with remission data in this review. The quality of reporting in the reviewed studies is poor, and further evaluation of citalopram, incorporating unpublished research, is necessary to evaluate more definitively its effectiveness in MDD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Apler A. Citalopram for major depressive disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published placebo-controlled trials. BMJ Open 2011;2:e000106. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000106

Funding: This study was supported by New South Wales Institute of Psychiatry.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The technical appendix is available from the corresponding author at alexapler@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Keller MB. Citalopram therapy for depression: a review of 10 years of European experience and data from US clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61:896–908 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montgomery SA, Djarv L. The antidepressant efficacy of citalopram. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;11(Suppl 1):29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrier IN. Treatment of major depression: is improvement enough? J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(Suppl 6):10–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller MB. Remission versus response: the new gold standard of antidepressant care. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(Suppl 4):53–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thase ME. Evaluating antidepressant therapies: remission as the optimal outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(Suppl 13):18–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). 3rd edn Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R). 3rd edn Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). 4th edn Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization The Ninth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-9). Geneva: World Health Organization, 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization The Tenth Revision of The International Classification of Diseases And Related Health Problems (ICD-10). 10th edn Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:382–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guy W, Bonato RR, eds. Manual for the ECDEU Assessment Battery 2. Chevy Chase, MD: National Institute of Mental Health, 1970 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman M, Posternak MA, Chelminski I. Derivation of a definition of remission on the Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale corresponding to the definition of remission on the Hamilton rating scale for depression. J Psychiatr Res 2004;38:577–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawley CJ, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T. Defining remission by cut off score on the MADRS: selecting the optimal value. J Affect Disord 2002;72:177–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan A, Brodhead AE, Kolts RL. Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale, the Hamilton depression rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials: a replication analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;19:157–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [Updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke WJ, Gergel I, Bose A. Fixed-dose trial of the single isomer SSRI escitalopram in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:331–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feighner JP, Overo K. Multicenter, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of citalopram in moderate-to-severe depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:824–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank MG, Hendricks SE, Burke WJ, et al. Clinical response augments NK cell activity independent of treatment modality: a randomized double-blind placebo controlled antidepressant trial. Psychol Med 2004;34:491–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gastpar M, Singer A, Zeller K. Comparative efficacy and safety of a once-daily dosage of hypericum extract STW3-VI and citalopram in patients with moderate depression: a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled study. Pharmacopsychiatry 2006;39:66–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepola UM, Loft H, Reines EH. Escitalopram (10-20 mg/day) is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;18:211–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendels J, Kiev A, Fabre LF. Double-blind comparison of citalopram and placebo in depressed outpatients with melancholia. Depress Anxiety 1999;9:54–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montgomery SA, Rasmussen JG, Lyby K, et al. Dose response relationship of citalopram 20 mg, citalopram 40 mg and placebo in the treatment of moderate and severe depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1992;6(Suppl 5):65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stahl SM. Placebo-controlled comparison of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors citalopram and sertraline. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:894–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danish University Antidepressant Group Citalopram: clinical effect profile in comparison with clomipramine. A controlled multicenter study. Danish University Antidepressant Group. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1986;90:131–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlsson I, Godderis J, Augusto De Mendonca Lima C, et al. A randomised, double-blind comparison of the efficacy and safety of citalopram compared to mianserin in elderly, depressed patients with or without mild to moderate dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15:295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyle CJ, Petersen HE, Overo KF. Comparison of the tolerability and efficacy of citalopram and amitriptyline in elderly depressed patients treated in general practice. Depress Anxiety 1998;8:147–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore N, Verdoux H, Fantino B. Prospective, multicentre, randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of escitalopram versus citalopram in outpatient treatment of major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;20:131–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw DM, Thomas DR, Briscoe MH, et al. A comparison of the antidepressant action of citalopram and amitriptyline. Br J Psychiatry 1986;149:515–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montgomery SA, Rasmussen JG, Tanghoj P. A 24-week study of 20 mg citalopram, 40 mg citalopram, and placebo in the prevention of relapse of major depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993;8:181–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robert P, Montgomery SA. Citalopram in doses of 20–60 mg is effective in depression relapse prevention: a placebo-controlled 6 month study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;10(Suppl 1):29–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Knorring AL, Olsson GI, Thomsen PH, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of citalopram in adolescents with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26:311–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner KD, Robb AS, Findling RL, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of citalopram for the treatment of major depression in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1079–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andersen G, Vestergaard K, Lauritzen L. Effective treatment of poststroke depression with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram. Stroke 1994;25:1099–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown ES, Vigil L, Khan DA, et al. A randomized trial of citalopram versus placebo in outpatients with asthma and major depressive disorder: a proof of concept study. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:865–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devos D, Dujardin K, Poirot I, et al. Comparison of desipramine and citalopram treatments for depression in Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord 2008;23:850–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fraguas R, da Silva Telles RM, Alves TC, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trial of citalopram for major depressive disorder in older patients with heart failure: the relevance of the placebo effect and psychological symptoms. Contemp Clin Trials 2009;30:205–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraus MR, Schafer A, Schottker K, et al. Therapy of interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C with citalopram: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gut 2008;57:531–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Koszycki D, et al. Effects of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy on depression in patients with coronary artery disease: the Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) trial. JAMA 2007;297:367–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nyth AL, Gottfries CG, Lyby K, et al. A controlled multicenter clinical study of citalopram and placebo in elderly depressed patients with and without concomitant dementia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992;86:138–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roose SP, Sackeim HA, Krishnan KR, et al. Antidepressant pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression in the very old: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:2050–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wermuth L, Sørensen PS, Timm S, et al. Depression in idiopathic Parkinson's disease treated with citalopram: a placebo-controlled trial. Nord J Psychiatry 1998;52:163–9 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altamura AC, Dell'Osso B, Buoli M, et al. Short-term intravenous citalopram augmentation in partial/nonresponders with major depression: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;23:198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumann P, Nil R, Souche A, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of citalopram with and without lithium in the treatment of therapy-resistant depressive patients: a clinical, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacogenetic investigation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:307–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montgomery SA, Loft H, Sanchez C, et al. Escitalopram (S-enantiomer of citalopram): clinical efficacy and onset of action predicted from a rat model. Pharmacol Toxicol 2001;88:282–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med 2008;358:252–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montgomery SA, Pedersen V, Tanghoj P, et al. The optimal dosing regimen for citalopram—a meta-analysis of nine placebo-controlled studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1994;9(Suppl 1):35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gorman JM, Korotzer A, Su G. Efficacy comparison of escitalopram and citalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: pooled analysis of placebo-controlled trials. CNS Spectr 2002;7(4 Suppl 1):40–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker NG, Brown CS. Citalopram in the treatment of depression. Ann Pharmacother 2000;34:761–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.