Abstract

Introduction

Insulin analogues have become increasingly popular despite their greater cost compared with human insulin. The aim of this study was to calculate the incremental cost to the National Health Service (NHS) of prescribing analogue insulin preparations instead of their human insulin alternatives.

Methods

Open-source data from the four UK prescription pricing agencies from 2000 to 2009 were analysed. Cost was adjusted for inflation and reported in UK pounds at 2010 prices.

Results

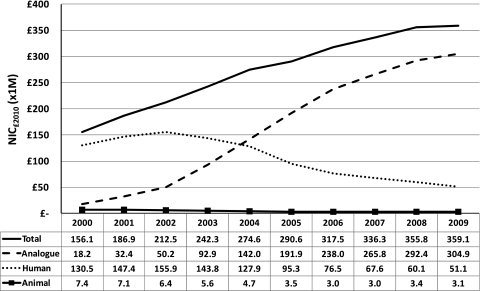

Over the 10-year period, the NHS spent a total of £2732 million on insulin. The total annual cost increased from £156 million to £359 million, an increase of 130%. The annual cost of analogue insulin increased from £18.2 million (12% of total insulin cost) to £305 million (85% of total insulin cost), whereas the cost of human insulin decreased from £131 million (84% of total insulin cost) to £51 million (14% of total insulin cost). If it is assumed that all patients using insulin analogues could have received human insulin instead, the overall incremental cost of analogue insulin was £625 million.

Conclusion

Given the high marginal cost of analogue insulin, adherence to prescribing guidelines recommending the preferential use of human insulin would have resulted in considerable financial savings over the period.

Article summary

Article focus

Insulin analogues have become increasingly popular in recent years.

Insulin analogues are more costly than their human insulin alternatives.

The aim of this cross-sectional study is to calculate the incremental cost to the National Health Service (NHS) of prescribing analogue insulin preparations instead of their human insulin alternatives.

Key messages

If all dispensations for analogue insulin between 2000 and 2009 had used a human insulin alternative, the NHS would have saved an estimated £625 million.

Given the high marginal cost of analogue insulin, adherence to prescribing guidelines recommending the preferential use of human insulin would have resulted in considerable financial savings over the period.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The calculation of the incremental cost of analogue insulin was based on an assumption that the same volume of insulin would be prescribed if patients were switched from analogue to human insulin.

Some data were missing from the Welsh Prescription Cost Analysis (PCA) and had to be estimated using PCAs from alternative countries in alternative years. This cost was adjusted for inflation and was unlikely to have impacted on the estimates as a whole as the net ingredient cost and volume of these products was small.

PCA only includes information on how much insulin was dispensed and not how many prescriptions were collected by patients with type 2 diabetes.

There is no definitive figure on how many patients with type 2 diabetes could have received human insulin instead of analogue insulin.

Introduction

The number of people diagnosed with diabetes in the UK has risen to 2.8 million,1–4 with approximately 90% of these having type 2 diabetes.5 Patients with type 1 diabetes require insulin from diagnosis, whereas those with type 2 diabetes tend to be switched to insulin later in the natural history of their disease.6

Insulin analogues were developed to better mimic the pharmacokinetic profile of endogenous insulin, thereby achieving more optimal onset or duration of action and simpler dosing regimens.7 8 Since their launch, the use of insulin analogues has increased steadily.9 In England, the annual net ingredient cost (NIC) of analogue insulin in 2004–2005 was £109.8 million (55% of total insulin cost), which had risen to £255.2 million (85.3% of total insulin cost) by 2009–2010.9 A similar trend was observed in the early 1980s when human insulin was introduced and the use of animal insulin decreased rapidly.10 This occurred despite a lack of evidence to indicate any benefits of human over animal insulin.7 10 The Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG) in Germany has questioned whether the benefits of insulin analogues are sufficient to outweigh their increased cost.11 12 In the UK, the National Institute for Heath and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of human neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin (NPH) as first-line therapy. Insulin glargine is only recommended in specific circumstances, and not as first-line therapy.13

Accordingly, the aim of this study was to characterise the pattern of insulin prescriptions dispensed between 2000 and 2009, inclusive, for the whole of the UK, and to evaluate the marginal financial cost to the National Health Service (NHS) of using analogue insulin instead of its equivalent human insulin preparation. This analysis formed the basis of the cost-saving estimates recently presented by the BMJ and Channel 4 News.14

Methods

Open-source data from the four prescription pricing agencies for England,15 Northern Ireland,16 Scotland17 and Wales18 were used in this study. The Prescription Cost Analyses (PCAs) for England, Northern Ireland and Wales describe the quantity and NIC of all NHS prescriptions dispensed in primary care in the constituent country. The NIC refers to the cost of the drug before any discounts, and does not include any dispensing costs or fees.19 The PCA for Scotland specifies gross ingredient cost, which is equivalent to NIC in the PCAs for England, Northern Ireland and Wales.17 The PCAs for the four countries from 2000 to 2009 were combined. Data were grouped into insulin types according to their molecular origin (analogue, human-sequence and animal-sequence) and also into individual insulin types (insulin soluble, insulin isophane, insulin zinc suspension mixed, insulin zinc suspension crystalline, biphasic isophane insulin, protamine zinc insulin, insulin aspart, insulin lispro, insulin detemir, insulin glargine, biphasic insulin aspart, biphasic insulin lispro and insulin glulisine). For the Welsh data from 2000 to 2004, it was necessary to calculate the quantity of each type of insulin dispensed from the NIC per unit quantity from the PCAs for England, Scotland or Northern Ireland, since the Welsh PCA data did not include this information until 2005. If the drug name in the PCA did not specify a presentation, that is a phial, a pre-filled pen or a cartridge, then it was assumed to be a phial.

All costs were adjusted for inflation, and they are reported in UK pounds at 2010 prices using the gross domestic product deflator published by HM Treasury.20 The incremental cost of analogue insulin was calculated by summing the NIC of analogue insulin and then subtracting the cost of dispensing the same volume of insulin of human origin.

The incremental cost of analogue insulin was also calculated by assuming that if patients prescribed analogue insulin had alternatively received human insulin, they would still have received the same presentation that is, a phial, a prefilled pen or a cartridge for a reusable pen device, since patients and clinicians favour the ease-of-administration offered by pen devices.21 22 Using data from a previous analysis of all prescribing costs for diabetes throughout the UK,23 we were further able to estimate the relative volumes of analogue and human insulin prescribed by the type of diabetes.

Results

Net ingredient cost of insulin in the UK, 2000–2009

Over the 10-year period, the NHS spent a total of £2732 million on insulin prescriptions. Prescriptions for analogue insulin accounted for £1629 million (59%), human insulin £1056 million (39%) and animal insulin £47.2 million (2%).

The total annual cost of insulin rose from £156 million in 2000 to £359 million in 2009, a 130% increase (figure 1). In 2000, the annual cost of analogue insulin was £18.2 million, which represented only 12% of total insulin cost, while the cost of human insulin was £131 million or 84% of the total insulin cost. Spending on analogue insulin increased from £192 million (66% of total insulin cost) in 2005, by which time all the currently marketed insulin analogues had been launched, to £305 million (85% of total insulin cost) in 2009. During the same period, the annual cost of human insulin fell from £95.3 million (33%) to £51.1 million (14%). The cost of animal insulin per year also decreased from £7.42 million (5%) in 2000 to just £3.07 million (1%) in 2009.

Figure 1.

The total annual cost of insulin prescriptions for the UK, 2000–2009. NIC, net ingredient cost.

Incremental cost of analogue insulin in the UK, 2000–2009

The unit cost of each insulin preparation is listed in table 1. Analogue insulin cost on average £2.31 per millilitre and was therefore 47% more expensive than human insulin at £1.57 per millilitre. In 2009, the mean NIC per millilitre was £1.27 for human insulin and £2.25 for analogue insulin. The NIC per millilitre of human and analogue insulin peaked in 2003 and 2004, respectively. Compared with 2004 values, the NIC per millilitre in 2009 had decreased by 27% for human insulin and by 7% for analogue insulin (table 2).

Table 1.

Net ingredient cost (NIC) and volume of analogue and human insulin by presentation for the UK, 2000–2009

| Insulin formulation | NIC£2010 | Volume (ml) | Percentage | NIC£2010/ml |

| Analogue insulin | £1 628 566 983 | 706 275 942 | £2.31 | |

| Pen | £705 567 792 | 285 036 913 | 40% | £2.48 |

| Penfill | £839 695 265 | 362 630 874 | 51% | £2.32 |

| Phial | £83 303 925 | 58 608 155 | 8% | £1.42 |

| Human insulin | £1 055 956 518 | 671 922 946 | £1.57 | |

| Pen | £218 790 437 | 117 962 069 | 18% | £1.85 |

| Penfill | £645 030 389 | 373 850 061 | 56% | £1.73 |

| Phial | £192 135 692 | 180 110 816 | 27% | £1.07 |

Table 2.

Average net ingredient cost (NIC) per millilitre in the UK, 2000–2009

| Year | NIC£2010/ml for human insulin | NIC£2010/ml for analogue insulin |

| 2000 | £1.60 | £2.24 |

| 2001 | £1.69 | £2.24 |

| 2002 | £1.76 | £2.25 |

| 2003 | £1.75 | £2.33 |

| 2004 | £1.74 | £2.41 |

| 2005 | £1.38 | £2.36 |

| 2006 | £1.37 | £2.34 |

| 2007 | £1.37 | £2.27 |

| 2008 | £1.35 | £2.30 |

| 2009 | £1.27 | £2.25 |

These unit costs were used to estimate the maximum, annual, incremental cost of dispensing analogue insulin assuming that all analogue prescriptions dispensed could have been alternatively prescribed as human insulin. Assuming 100% conversion, the annual incremental cost of analogue insulin increased from £5.18 million in 2000 to £133 million in 2009 (table 3). Overall, for the 10-year period, the total incremental cost of analogue insulin was £625 million at 100% conversion and £312 million at 50% conversion. Between 2005 and 2009, the incremental cost of analogue insulin was £538 million at 100% conversion and £269 million at 50% conversion.

Table 3.

Incremental cost of analogue insulin in the UK, 2000–2009

| Year | Incremental cost (£2010) (assuming 100% conversion of analogue to human insulin) | Incremental cost (£2010) (assuming 50% conversion of analogue to human insulin) |

| 2000 | £5 183 001 | £2 591 500 |

| 2001 | £8 065 849 | £4 032 924 |

| 2002 | £10 795 155 | £5 397 578 |

| 2003 | £23 143 753 | £11 571 877 |

| 2004 | £39 529 331 | £19 764 666 |

| 2005 | £79 448 570 | £39 724 285 |

| 2006 | £98 317 347 | £49 158 673 |

| 2007 | £106 139 197 | £53 069 598 |

| 2008 | £121 376 170 | £60 688 085 |

| 2009 | £132 895 201 | £66 447 601 |

| Total | £624 893 574 | £312 446 787 |

Estimated cost by diabetes type

Patients with type 2 diabetes accounted for an estimated £86.0 million of NHS expenditure on human and analogue insulin in 2000, increasing to £229 million (+166%) in 2009. For type 1 diabetes these values were £62.7 million and £127 million, respectively (+103%). Over the entire period, the total cost of insulin prescribing for type 2 diabetes was £950 million for insulin analogues and £708 million for human insulin (see table 4). The incremental cost of analogue insulin for patients with type 2 diabetes was estimated at £306 million at 100% conversion and £153 million at 50% conversion.

Table 4.

Estimated change in net ingredient cost (NIC) and volume of human and analogue insulin prescribed to patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the UK, 2000–2009

| Year | NIC£2010 for type 1 diabetes |

NIC£2010 for type 2 diabetes |

Volume (ml) for type 1 diabetes |

Volume (ml) for type 2 diabetes |

||||

| Total analogue | Total human | Total analogue | Total human | Total analogue | Total human | Total analogue | Total human | |

| 2000 | £11 228 382 | £51 444 334 | £6 923 103 | £79 075 954 | 5 038 092 | 33 056 509 | 3 050 474 | 48 350 233 |

| 2001 | £17 858 968 | £55 211 316 | £14 564 748 | £92 155 033 | 8 001 813 | 33 577 135 | 6 443 335 | 53 816 755 |

| 2002 | £25 764 159 | £57 242 261 | £24 410 582 | £98 670 067 | 11 520 222 | 33 039 547 | 10 827 941 | 55 441 680 |

| 2003 | £45 316 250 | £49 420 126 | £47 585 514 | £94 338 575 | 19 667 109 | 28 663 444 | 20 145 487 | 53 383 153 |

| 2004 | £65 066 374 | £40 577 834 | £76 937 127 | £87 354 455 | 27 296 077 | 23 712 414 | 31 672 369 | 49 905 829 |

| 2005 | £82 462 748 | £28 231 889 | £109 393 916 | £67 039 353 | 35 341 564 | 21 196 772 | 45 841 398 | 47 609 677 |

| 2006 | £97 342 547 | £21 284 207 | £140 625 903 | £55 238 238 | 42 215 106 | 15 771 316 | 59 651 444 | 40 046 916 |

| 2007 | £105 277 447 | £17 662 770 | £160 494 779 | £49 900 346 | 46 896 096 | 13 048 606 | 70 028 562 | 36 438 609 |

| 2008 | £113 178 916 | £14 924 884 | £179 215 091 | £45 134 839 | 49 542 256 | 11 113 432 | 77 455 050 | 33 486 730 |

| 2009 | £114 597 696 | £12 375 736 | £190 322 726 | £38 711 902 | 51 543 528 | 9 734 567 | 84 098 018 | 30 547 933 |

| Total | £678 093 486 | £348 375 355 | £950 473 489 | £707 618 762 | 297 061 863 | 222 913 742 | 409 214 078 | 449 027 514 |

Incremental cost of analogue insulin in the UK taking insulin presentation into account, 2000–2009

Human insulin is more likely to be dispensed as a phial when compared to insulin analogues which are typically administered using a pen device (table 1). If all those receiving analogue insulin had been dispensed human insulin instead but the presentation had remained the same (ie, a phial, a pen or a pen-fill device), then the incremental cost of analogue insulin in the UK between 2000 and 2009 would have been £271 million at 50% conversion and £541 million at 100% conversion, compared with £625 million at 100% conversion (table 3) if insulin presentation is not take into account.

Discussion

Since their launch, insulin analogues have had an increasing impact on the amount of resources used to manage diabetes. The annual inflation-adjusted cost to the NHS of insulin increased from £156 million in 2000 to £359 million in 2009 (a twofold increase). During the same period, annual NHS spending on analogue insulin increased from £18 million (12% of total insulin cost) to £305 million (85% of total insulin cost), while annual NHS spending on human insulin fell from £130 million (84%) to £51.1 million (14%). If all dispensations for analogue insulin between 2000 and 2009 had used the equivalent human insulin, we estimate the NHS would have saved £625 million.

While it has been shown that insulin analogues are associated with reduced weight gain, less hypoglycaemia (particularly nocturnal), improved lowering of postprandial glucose and improved dosing schedules, most commentators agree that these benefits are modest in comparison to human insulin.7 8 24 However, the cost effectiveness of analogue insulin is likely to vary depending on the type of diabetes, the clinical characteristics of the individual patient and the particular type of analogue insulin. For example, rapid-acting insulin analogues in patients with type 1 diabetes are likely to be a cost-effective use of finite healthcare resources.25 In the NICE guidance for the management of patients with type 2 diabetes, the use of human insulin is recommended as first-line therapy, and long-acting analogues such as insulin glargine and premixed insulin are only recommended in certain specific circumstances.26 The NICE has determined that insulin glargine borders on being cost effective at current willingness to pay thresholds in patients with type 1 diabetes but that it is not cost effective in type 2 diabetes.13 In Germany, the IQWiG disputes the value of insulin analogues in type 2 diabetes.11 12 In addition, the Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC) in New Zealand has approved insulin glargine but only as second-line therapy and has only recommended its use in those who are allergic to conventional insulin or have failed to control their diabetes with conventional insulin.27 A similar recommendation has been made by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health where human insulin is recommended as first-line therapy and insulin analogues are only recommended for patients who experience significant hypoglycaemia.28 The longest trial comparing insulin glargine with insulin isophane concluded that there was a similar progression to retinopathy with the two agents but less improvement in glycated haemoglobin levels for the more expensive product, insulin glargine (0.2%, p=0.0053).29 Furthermore, although the period from 1997 to 2007 saw the introduction of insulin analogues and a general increase in diabetes-related care, this was not accompanied by an improvement in glycated haemoglobin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin.30 There is currently no systematic means of measuring the other clinical benefits associated with analogue insulin, such as rate of symptomatic or nocturnal hypoglycaemia, making it difficult to judge the real-world cost effectiveness of these drugs. An analysis of open-source Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data shows that growth in hospital admissions for hypoglycaemia has exceeded growth in the prescribing of insulin.31

The increase in the use of analogue insulin is likely to be due in part to successful marketing. Some of the manufacturers of insulin analogues also provided professional support to general practitioners at the time their analogue insulin was marketed, although this was not conditional on the doctor prescribing their insulin.14 Insulin analogues were also available in new devices that may be more appealing to patients and easier to use than the devices used to administer human insulin.14 The fact that 40% of analogue insulin was prescribed as a prefilled pen device compared with just 18% of human insulin supports this suggestion. Finally, a move to patented insulin products has notable commercial benefits for manufacturers.

Since the introduction of insulin analogues, some human insulin products have been withdrawn. Patients using these products have switched to an alternative product containing either human insulin or an insulin analogue. In 2005, Novo Nordisk discontinued Actrapid penfills and recommended NovoRapid as an alternative product. At the same time, they also withdrew Insulatard Flexpen and Monotard from their range of human insulin.32 Since the withdrawal of Mixtard 30 at the end of 2010, its 90 000 users will have been changed to an alternative product. It will be interesting to repeat this study to assess whether these patients have been switched to human insulin (the equivalent product is Humulin M3) or indeed to analogue insulin. The Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin has estimated that if all users of Mixtard 30 were switched to NovoMix 30, it would result in an increase in cost of £9 million to the NHS in England alone.33

The increase in the annual inflation-adjusted NHS cost between 2000 and 2009 can be partly accounted for by the increase in the prevalence of diabetes in the UK during this time. In 1996, it was estimated that 1.4 million people in the UK had diabetes.34 By 2004, this figure had risen to 1.8 million35 and to 2.6 million by 2009.36 Patients with type 2 diabetes can be managed with one or more of diet, oral glucose-lowering medication or insulin, whereas patients with type 1 diabetes are dependent on exogenous insulin. However, the estimated volume of analogue and human insulin dispensed to patients with type 2 diabetes is far greater than for type 1 diabetes. This can be explained by the prevalence of type 2 and type 1 diabetes in the UK. It has been estimated that approximately 90% of people with diabetes in the UK have type 2 diabetes. It can be further explained by the nature of type 2 diabetes, which is characterised by insulin resistance. Patients with type 2 diabetes are more likely to be overweight or obese than patients with type 1 diabetes.37 Therefore, those with type 2 diabetes using insulin often receive higher insulin doses. Furthermore, results from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) may have influenced the increased prescribing of insulin to patients with type 2 diabetes so that lower HbA1c levels could be obtained.38

This study had inherent limitations. The calculation of the incremental cost of analogue insulin was based on the assumption that the same volume of insulin would be prescribed if patients were switched from analogue to human insulin. The PCA for Wales from 2000 to 2004 did not include the quantity of insulin dispensed which was necessary to calculate the incremental cost. The quantity, therefore, had to be calculated from the NIC per quantity figures from the PCAs for England, Scotland and Northern Ireland. However, certain products in the Welsh PCA were not available for the other regions for the same year, so figures from the previous years had to be used and adjusted for inflation. Some drugs were listed only under their generic name in the Welsh PCA and so a weighted-average NIC per quantity for the branded products in the English PCA was used. The same approach was taken when the drug name description did not specify whether the cartridge size was 1.5 ml or 3 ml (when these were the only cartridge sizes on the market). In addition, there were two drug names, Human Actraphane and Human Protaphane phials, which had no matches in any of the other PCAs for any year. These are Novo Nordisk products, which tend to carry the same cost per unit depending on whether they are phial, penfill or prefilled pen and which is not dependent on what type of human insulin is in the device. Therefore, the NIC per quantity used for these two products was the NIC per quantity of the other Novo Nordisk phials. These assumptions were unlikely to have impacted upon the estimates as a whole, since the NIC and the volume of these products were small.

Another limitation was that the PCA only tells us how much of each type of insulin was dispensed; thus, there was no way of determining how much insulin was dispensed to patients with type 2 diabetes specifically. However, it is likely that the level of type 1 diabetes remained relatively constant over the study period, while the number of patients with type 2 diabetes is known to have increased considerably.39

The assumption that all patients using insulin analogues could be equally well treated with human insulin is also likely to be unrealistic. Dr Adler, chair of the NICE guidance committee, has suggested that 90% of patients with type 2 diabetes could receive human insulin instead of long-acting insulin analogues, with around two-thirds of these patients remaining on human insulin.14 Currently, however, there is no definitive figure for how many people with diabetes could have received human insulin instead of analogue insulin. The purpose of this study was to calculate a monetary value to raise awareness of the cost implications at a population level of prescribing analogue insulin instead of human insulin rather than to suggest an exact percentage of patients with diabetes who could be equally well treated with human instead of analogue insulin.

At the macroeconomic level, we know that the rise of insulin analogues has had a substantial financial impact on the NHS, yet over the same period there has been no observable clinical benefit to justify that investment. It is likely that there was and is considerable scope for financial savings. Most worryingly, the clinical role and safety of insulin for use in people with type 2 diabetes is being questioned.40–43

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Holden SE, Poole CD, Morgan CL, et al. Evaluation of the incremental cost to the National Health Service of prescribing analogue insulin. BMJ Open 2011;2:e000258. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000258

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: CP has received payment for lectures from Novo Nordisk; CP, CC and CM have carried out consultancy work for pharmaceutical companies that manufacture insulin.

Contributors: CP conceived and designed the study, CM and SH collated and analysed the data, CC, CP and SH interpreted the data, SH drafted the article and all authors were involved in the revision of the article. CC approved the final version to be published and is overall guarantor.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned by the BMJ and Channel 4 News; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data used in this study were obtained from the four UK prescription pricing agencies and are open–source.

References

- 1.NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre Prevalence Data Tables. 2010. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/supporting-information/audits-and-performance/the-quality-and-outcomes-framework/qof-2009-10/data-tables/prevalence-data-tables

- 2.Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety Quality and Outcomes Framework Achievement Data at Local Commissioning Group (LCG) Level 2009/10. 2010. http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/index/hss/gp_contracts/gp_contract_qof/qof_data/primary_care-qof.htm

- 3.NHS National Services Scotland, Information Services Division GMS—Quality & Outcomes Framework—2008/09 QOF Prevalence Data. 2010. http://www.isdscotland.org/isd/6431.html

- 4.Welsh Assembly Government, Statistics for Wales QOF Disease Registers. 2010. http://www.statswales.wales.gov.uk/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=24813

- 5.Diabetic-Life.co.uk Number of UK Diabetics Increases. 2010. http://www.diabeticlife.co.uk/news/2010/Oct/number-of-uk-diabetics-increases.html

- 6.British National Formulary 60 (September). London: BMJ Publishing Group, Pharmaceutical Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holleman F, Gale EA. Nice insulins, pity about the evidence. Diabetologia 2007;50:1783–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gough SC. A review of human analogue insulin trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007;77:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care Forty Per cent Rise in Cost and Number of Drug Items Prescribed to Treat Diabetes in England, NHS Information Centre report shows. 2010. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/news-and-events/press-office/newsreleases/forty-per-cent-rise-in-cost-and-number-of-drug-items-prescribed-to-treat-diabetes-in-england-nhs-information-centre-report-shows

- 10.Richter B, Neises G. ‘Human’ insulin versus animal insulin in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD003816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care Rapid-acting Insulin Analogues in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus Type 2: Final Report; Commission A05–04. 2008. https://www.iqwig.de/download/A05-04_Final_Report_Rapid-acting_insulin_analogues_for_the_treatment_of_diabetes_mellitus_type_2.pdf [PubMed]

- 12.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care [Long-acting insulin analogues in the treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2: final report; commission A05–03] (In German). 2008. https://www.iqwig.de/download/A05-03_Executive_summary_Long_acting_insulin_analogues_in_the_treatment_of_diabetes_mellitus_type_2.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Guidance On the Use of Long-acting Insulin Analogues for the Treatment of Diabetes—Insulin Glargine. London: NICE, 2002. (Technology appraisal 53). http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11482/32518/32518.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen D, Carter P. How small changes led to big profits for insulin manufacturers. BMJ 2010;341:c7139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care PACT Data for England. 2010. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/primary-care/prescriptions

- 16.HSC Business Service Organisation Prescription Cost Analyses. Health and Social Care in Northern Ireland, 2010. http://www.centralservicesagency.com/display/statistics [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS National Services Scotland, Information Services Division Prescription Cost Analysis for Scotland. 2010. http://www.isdscotland.org/isd/2241.html

- 18.NHS Wales, Prescribing Services Prescription Cost Analysis. 2011. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgid=428&pid=13533

- 19.NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care Prescription Cost Analysis, England 2009. Glossary. 2010. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/prescostanalysis2009/PCA_2009_Glossary.pdf

- 20.HM Treasury Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Deflators. 2010. http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/data_gdp_fig.htm

- 21.Korytkowski M, Bell D, Jacobsen C, et al. ; and the FlexPen Study Team A multi-center, randomized, open-label, comparative, two-period, crossover trial of preference, efficacy and safety profiles of a prefilled, disposable pen and conventional vial/syringe for insulin injection in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther 2003;25:2836–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graff MR, McClanahan MA. Assessment by patients with diabetes mellitus of two insulin pen delivery systems versus a vial and syringe. Clin Ther 1998;20:486–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Currie CJ, Gale EA, Poole CD. Estimation of primary care treatment costs and treatment efficacy for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the United Kingdom between 1997 and 2007. Diabet Med 2010;27:938–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Home PD, Fritsche A, Schnizel S, et al. Meta-analysis of individual patient data to assess the risk of hypoglycaemia in people with type 2 diabetes using NPH insulin or insulin glargine. Diabetes Obes and Metab 2010;12:772–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cameron CG, Bennett HA. Cost effectiveness of insulin analogues for diabetes mellitus. CMAJ 2009;180:400–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Type 2 Diabetes: The Management of Type 2 Diabetes. London: NICE, 2008. (Clinical guideline 66). http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG66NICEGuideline.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moodie P. More from PHARMAC on long-acting insulin analogues: insulin glargine now funded. N Z Med J 2006;119:118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Insulin Analogue Therapy. http://www.cadth.ca/en/products/optimal-use/insulin-analog-therapy

- 29.Rosenstock J, Fonseca V, McGill JB, et al. Similar progression of diabetic retinopathy with insulin glargine and neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a long-term randomised open-label study. Diabetologia 2009;52:1778–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Currie CJ, Peters JR, Tynan A, et al. Survival as a function of HbA1c in people with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2010;375:481–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hospital Episode Statistics (HES Online) Primary Diagnosis: 4 Character. 2010. http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=214

- 32.Anonymous. Actrapid cartridges to be discontinued after December. Pharm J 2005;274:785 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anonymous. Mixtard 30—going, going, gone? Drug Ther Bull 2010;48:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diabetes UK Diabetes in the UK 2010: Key Statistics on Diabetes. London: Diabetes UK, 2010. http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Documents/Reports/Diabetes_in_the_UK_2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diabetes UK Report and Statistics. Diabetes in the UK 2004. London: Diabetes UK, 2004. http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Professionals/Publications-reports-and-resources/Reports-statistics-and-case-studies/Reports/Diabetes_in_the_UK_2004/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diabetes UK Reports and Statistics. Diabetes Prevalence 2009. London: Diabetes UK, 2009. http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Professionals/Publications-reports-and-resources/Reports-statistics-and-case-studies/Reports/Diabetes-prevalence-2009/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daousi C, Casson IF, Gill GV, et al. Prevalance of obesity in type 2 diabetes in secondary care: association with cardiovascular risk factors. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:280–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holman RR, Paul SR, Bethel A, et al. 10-Year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes (UK PDS 80). N Eng J Med 2008;359:1577–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan CL, Peters JR, Currie CJ. The changing prevalence of diagnosed diabetes and its associated vascular complications in a large region of the UK. Diabet Med 2010;27:673–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rensing KL, Reuwer AQ, Arsenault BJ, et al. Reducing cardiovascular disease risk in diabetic persons with established macrovascular disease: can insulin be too much of a good thing? Diabetes Obes Metabol. In press. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nandish S, Bailon O, Wyatt J, et al. Vasculotoxic effects of insulin and its role in atherosclerosis: what is the evidence? Curr Atheroscler Rep 2011;13:123–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebovitz HE. Insulin: potential negative consequences of early routine use in persons with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Supplement 2):s225–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Currie CJ, Johnson JA. The safety profile of exogenous insulin in people with type 2 diabetes: justification for concern. Diabetes Obes Metab. In press. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01469.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.