Abstract

Rhinolith is like a stone formation within the nasal cavity. Although stones rarely form in the nasal cavity, the findings of calcified objects or stones anywhere within the body has long been a subject of interest. Though infrequently observed, nasal concretions can be the source of bad smell from the nose and therefore a social concern for the patient. The salient features of such Rhinoliths and their relevance to clinical practice are discussed and a case of a large Rhinolith is presented in this article. So as to enable the attending clinician to be aware of this forgotten entity, which requires a high index of suspicion.

Introduction

Rhinolith (from the Greek rhino meaning nose, and lithos meaning stone) are rare. They are calcareous concretions that are formed by the deposition of salts on an intranasal foreign body. This intranasal foreign body which may incidently or accidently access the nasal cavity then act as the nucleus (thus becoming a focal point) for encrustation. Nasal foreign bodies can either be endogenous or exogenous. Dessicated blood clots, ectopic teeth, and bone fragments are examples of endogenous causes whereas exogenous causes can include fruit seeds, plant material, beads, cotton wool, and at times the material used for taking dental impression rhinoliths can have various clinical presentations. Surgical removal is the treatment of choice. A high index of suspicion is required for the diagnosis of such a forgotten entity. Rhinolithiasis was first described by Bartholin in 1654. The etiology is not always detected, and it may be exogenous (such as grains, small stone fragments, plastic parts, seeds, insects, glass, wood and others), or endogenous, resulting from dry secretion, blood clots, mucosal necrosis and tooth fragments, which operate as foreign bodies.

Foreign bodies normally access the site anteriorly, but they may occasionally reach the nasal cavity through the posterior choanae owing to cough or vomiting. Foreign bodies are normally introduced during childhood, occupying the nasal floor in most situations. Its presence causes local inflammatory reaction, leading to deposits of carbonate and calcium phosphate, magnesium, iron and aluminium, in addition to organic substances such as glutamic acid and glycine, leading to slow and progressive increases in size. Symptoms are normally progressive unilateral nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea (usually purulent and fetid), cacosmia and epistaxis. Other less common symptoms include headaches, facial pain and epiphora.

Case Report

A 31 year old female presented with complains of prolonged runny nose with foul smell, and at times bloody nasal discharge for the last five years. There were no constitutional symptoms. There was no history of trauma, foreign body insertion or any systemic illness. Otolaryngeal clinical examination revealed deviated nasal septum towards the left side. The right nasal cavity appeared wide with atrophic changes. There was a hard mass lying on the floor of the right nasal cavity which was irregular in shape with a rough surface and was slightly mobile but tender and with bleeding tendency. A diagnosis of rhinolith was clinically made and the patient was admitted for removal of the rhinolith.

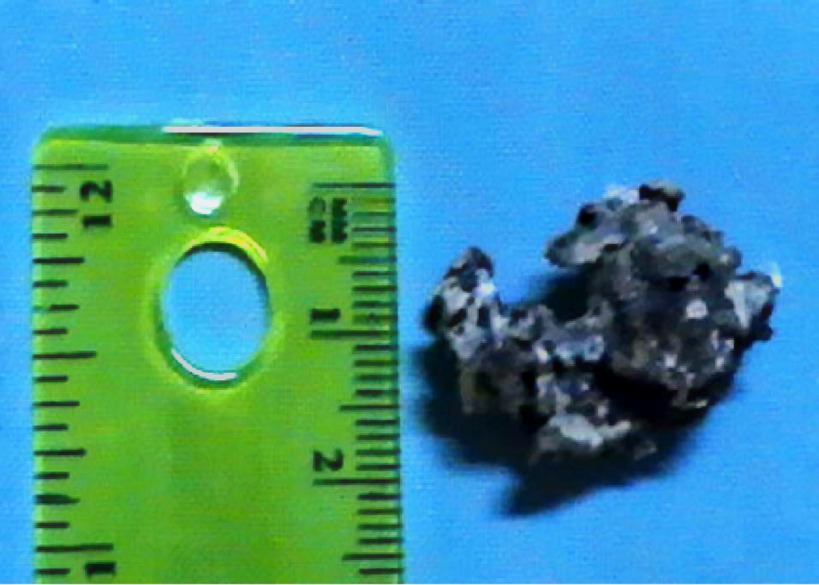

Under General Anaesthesia, the nasal cavities were inspected by 0 degree nasal rigid endoscope. A rhinolith was found lying impacted between the inferior turbinate and septum in the middle of the right nasal cavity. It was gently mobilised and pushed posteriorly into the nasopharynx from where it was picked up and removed. Technically, pushing the rhinolith posteriorly was easier than delivering it anteriorly. The specimen measured 3 cm * 1.5 cm * 1.5 cm with irregular shape and rough surface. (Figs. 1, 2)

Figure 1.

Rhinolith measuring 3 cm.

Figure 2.

Width of Rhinolith measuring 1.5 cm.

The estimated blood loss was approximately 100 ml. The right nasal cavity was packed with medicated ribbon gauze anteriorly and bloster dressing was applied. The nasopharynx was inspected transorally with mirror-found and was found to be normal. The patient was smoothly extubated and transferred to the recovery room.

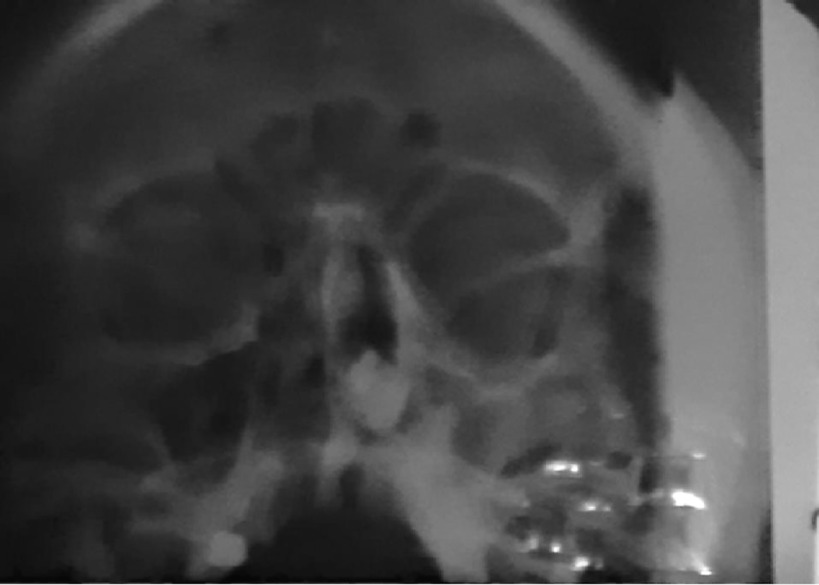

Figure 3.

X-ray showing the Rhinolith as an opaque shadow in the right nasal cavity.

Discussion

Rhinoliths are rare. They are calcareous concretions that are formed by the deposition of salts on an intranasal foreign body.1 Although the pathogenesis of rhinoliths remains unclear, a number of factors are thought to be involved in their formation. These include entry and impaction of a foreign body into the nasal cavity, acute and chronic inflammation, obstruction and stagnation of nasal secretions, and precipitation of mineral salts.2 Usually, it takes a while for a rhinolith to form, therefore the course of development and progression of this disease is believed to take a number of years.

Most patients complain of purulent rhinorrhea and/or ipsilateral nasal obstruction. Other symptoms include fetor, epistaxis, sinusitis, headache and, in rare cases, epiphora. In some patients, rhinoliths are discovered incidentally. Examination should include anterior rhinoscopy and rigid endoscopy. Computed tomography of the paranasal sinuses can accurately determine the site and size of the rhinolith and identify any coexisting sinus disease which may also require treatment.3 Diagnosis can be established by keeping a high index of suspicion based on symptomatology, history of foreign body introduction into the nose, physical examination and complementary tests. Simple X-ray and paranasal sinuses CT scan supports the diagnosis through the presence of calcified concretions in the nasal fossa, in addition to supporting the planning of surgical approach.

Diagnosis is sometime also made incidentally through routine examination or revealed by imaging examinations conducted for other reasons, such as dental treatment.

Treatment consists of removal of the rhinolith and the surgical approach chosen depends on the location and size of the rhinolith and the presence (if any) of complications, but most of which may be removed endonasally.

Conclusion

Although Rhinoliths are rare, attending clinicians should be aware of this entity. It requires a high index of suspicion when dealing with nasal symptoms such as progressive unilateral nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea (usually purulent and fetid), cacosmia and unilateral nasal bleeding.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Miss Nasra Eid Mubarak Al Hashmi of the secretarial pool for typing the manuscript. The authors gratefully acknowledge the encouragement and support of Dr. Mohammed Al Farsi. Executive Director Sur Hospital and Mr. Mohammed Bin Khamees Al Farsi, Director General of Health Services, South Sharqiya Region.

References

- 1.Polson CJ. On rhinoliths. J Laryngol Otol 1943;58:79-116 . 10.1017/S0022215100011002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezsiás A, Sugar AW. Rhinolith: an unusual case and an update. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1997. Feb;106(2):135-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadi U, Ghossaini S, Zaytoun G. Rhinolithiasis: a forgotten entity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002. Jan;126(1):48-51. 10.1067/mhn.2002.121018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]