Abstract

Objectives

Measles is a highly infectious immunizable disease with potential for eradication but is still responsible for high mortality among children, particularly in developing nations like Nigeria. This study aims to determine the hospital based prevalence of measles, describe the vaccination status of children managed for measles at the Federal Medical Centre, Bida, Niger state and to identify the parental disposition to measles vaccination.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study carried out over a period of 18 months beginning from July 2007. All children with a diagnosis of measles made clinically and reinforced with serological test in the WHO Measles, Rubella and Yellow Fever laboratory in Maitama District Hospital, Abuja were recruited. Informed consent was obtained from the parents/care givers. Structured questionnaire was used to obtain information and data analysis was by SPSS version 15.

Results

One hundred and nine children were managed for measles, constituting 8% of total admission over the study period. The male to female ratio was 1.2:1. Of the 109 children with measles, 90 (82%) did not receive measles vaccination. Eighty-eight (80%) of the parents or guardian felt vaccination was bad for various reasons. Of the 23 (21.1%) children whose parents or guardians were positively disposed to vaccination, one death was recorded while the remaining seven deaths were recorded among children whose parents were negatively disposed to vaccination. All the deaths were in the non-vaccinated group below 2 years of age.

Conclusion

Measles is still a major health burden in our community. The majority of affected children were not vaccinated due to negative parental disposition. Continuous health education is required for change the disposition of the parents/guardian and improve vaccination coverage to minimize measles associated morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Measles, Vaccination, Parental disposition, Outcome

Introduction

Measles is an old disease; old enough to merit being referred to as the First disease.1 Since its emergence thousands of years ago, it has caused millions of deaths largely due to an increased susceptibility of measles infected persons to secondary bacterial and other viral infections. This period of increased susceptibility lasts for several weeks to months after the onset of measles rash,2 and is attributed to a prolonged state of immune suppression commonly referred to as post measles anergy. Most deaths associated with measles are due to secondary bacterial pneumonia.3 Immunization consequent upon effective vaccination has been successful in many developed nations such as Canada and United Kingdom. In Canada, sustained transmission has been eliminated by the current schedule and high vaccine coverage. However, imported cases still occur though secondary spread from these imported cases is self-limited and involves the few Canadians in the isolated groups that are philosophically opposed to immunization. The secondary spread to the general population is very limited.4,5

Measles is a highly infectious immunizable disease with potential for eradication but is still responsible for high mortality among children particularly in developing nations like Nigeria. Currently, Nigeria is one of the 47 countries in the world where the burden of measles is highest and where it is still responsible for the highest number of vaccine preventable death. The current national measles vaccination coverage is 62% with a very wide variation in the country that has once achieved coverage of 80% with routine immunization. The disposition of parents or guardians of the Nigerian children is however key to improved vaccination coverage, and by extension to significant reduction in the morbidity and mortality associated with measles. The lack of data on measles in Bida, Niger state of Nigeria necessitated the study.

In the United Kingdom by 1995, uptake of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination exceeded 90%. Increasing vaccination coverage was mirrored by a fall in notifications from around half a million cases annually in the 1960s and culminated in the interruption of endemic measles transmission.4x

This is not yet so in several developing nations such as Nigeria. In Nigeria, the routine immunization program which was started in 1979 as an initiative of World Health Organization (WHO) Expanded program on Immunization (EPI). It targets childhood killer diseases such as Tuberculosis, Diphtheria, Pertusis, Tetanus, Poliomyelitis and Measles. In Nigeria, EPI was upgraded to National Program on Immunization (NPI) in 1997 to demonstrate the commitment of the country and additional vaccines against Hepatitis B and Yellow fever were introduced.5

Recently, there have been increased activities by various health regulatory bodies in the control of measles throughout the world, Nigeria inclusive.5,6 As part of this demonstration of commitment by the Federal Government of Nigeria and Niger State ministry of health in the prevention and treatment of measles collaborated with WHO and national and sub-national laboratories were set up in strategic places.7 In Nigeria, one such laboratory is located at Maitama District Hospital, Abuja. Serologic kits were used for laboratory confirmation of measles according to the WHO standards.

With all these in place, a need to determine the current prevalence, vaccination status of measles infected children and its immediate outcome became important. Furthermore there is the need to establish relevant data which are lacking on measles in the Federal Medical Centre, Bida, the largest referral health centre and the only tertiary hospital in the Niger state, Nigeria.

Methods

All children admitted over a period of 18 month beginning from July 2007 with measles were studied at the Federal Medical Centre, Bida, Niger State. Informed consent was obtained from their parents or care givers. Structured questionnaire was used to obtain information on age, gender, main symptoms, duration, and the vaccination status as regards the routine NPI of children presenting with measles from their parents or guardians. Information on disposition of parents or guardians of measles infected children to measles vaccination was also sought. The duration of admission for admitted children with measles infection and the immediate outcome were similarly documented.

Measles was clinically diagnosed by presence of fever, maculo-papular (non-vesicular) generalized rash and cough, coryza or conjunctivitis. Blood samples from children diagnosed with measles were pooled and sent to the WHO Measles, Rubella and Yellow fever laboratory in District Hospital, Maitama, Abuja on regular basis by health officers from the Niger state ministry of Health. ELISA technique was used in detecting measles IgM according to WHO standard.8 Components of a specimen collection kit supplied by the WHO for measles diagnosis have been specified and are suitable for distributing to facilities collecting samples from suspected measles subjects. The basic kit for blood collection consisted of 5 ml vacutainer tube (non-heparinized) with 23 g needle, tourniquet, sterilizing swabs, serum storage vials, specimen labels, band aid, ziplock plastic bags, specimen referral form, and cold box with ice packs. Data analysis was done with SPSS version 15. All patients were offered the standard care and counseling as required.

Results

A total of 1,364 children were admitted over the 18 months study period at the Federal Medical Centre, Bida. One hundred and nine (8.0%) of them had measles and their ages ranged from 6 months to 6 years. The age distribution of all the managed children is as shown in Table 1, with 22 (20.2%) infants, 84 (48.8%) under-fives (1-4 years), 3 (2.8%) children aged 6-11 years, and none (0%) above 12 years was managed for measles.

Table 1. Age distribution of all children managed over the study period.

| Age group (years) | Measles (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 (Infancy) | 22 (20.2) | 557 |

| 1-5 (Under-five) | 84 (77.1) | 665 |

| 6-12 (school age) | 3 (2.7) | 90 |

| Over 12 (Adolescent) | 0 (0) | 52 |

| Total | 109 (100) | 1,364 |

The male to female ratio of measles children was 1.2:1. Ninety (82.6%) children did not receive measles vaccination. Fifty (55.6%) of the children without measles vaccination did not receive any other vaccines meant for routine childhood immunization in the Nigerian NPI schedule. Nineteen children (17.4%) were fully vaccinated according to the NPI schedule. Of the 19 that were fully immunized, 12 were males and 7 were females (χ2 =0.76, p =0.38).

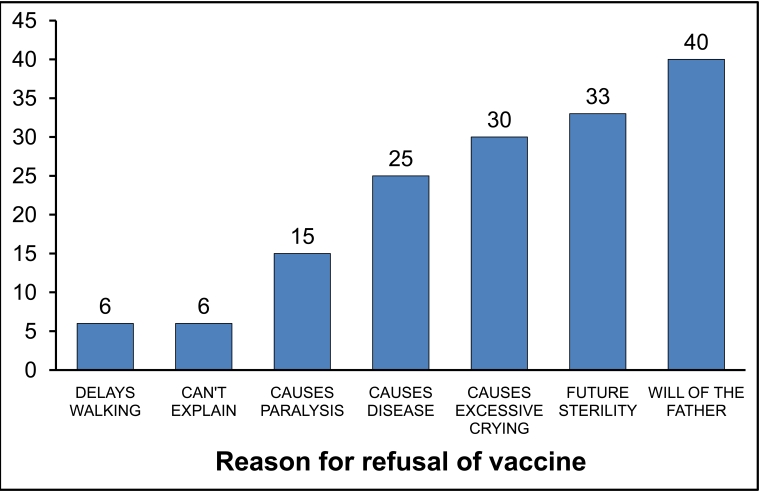

Eighty-eight (80.7%) of the parents or guardians felt immunization was bad for various reasons ranging from future sterility (33), disease causation (25), will of the father (40), to causing paralysis (15), excessive crying (30) and delayed walking (6), Cannot explain (6) as shown in Fig. 1. Of the 23 children whose parents felt immunization was good for their protection, one death was recorded while the remaining seven deaths were recorded among children whose parents felt immunization was bad for one reason or the other. This difference was statistically significant (Yate's corrected <chi>2 = 13.21, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Monthly distribution of Measles over the study period

All the measles associated mortality occurred among the children without measles vaccination and they were among children with age 48 months and below. Overall, 99 children were successfully managed and discharged, eight died (5 males and 3 females) putting the case fatality at 7.3%, and two left against medical advice. Monthly distribution of cases was grouped in a quarterly manner, (Table 2). Thirteen (11.9%) of the 109 cases occurred during the rainy seasons.

Table 2. Quarterly distribution of Cases of measles over the study period.

| Quarter | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| July –September 2007 | 5 (4.6) |

| October-December 2007 | 21 (19.3) |

| January –March 2008 | 33 (30.3) |

| April – June 2008 | 3 (2.7) |

| July –September 2008 | 5 (4.6) |

| October-December 2008 | 42 (38.5) |

| Total | 109 (100) |

Discussion

The hospital based prevalence of measles in Bida, to our knowledge, has not been documented before this study. Even though the study was hospital based, it gave an insight as to what may be obtainable in the community. Children below the age of 5 years accounted for the majority of the morbidity and those below 2 years accounted for most of the mortality in this study. This emphasizes the age-groups most prone to the infection. Previous studies have shown the latter to be the most vulnerable and hence the need for booster doses or supplementary immunization as it is being done on National Immunization Days (NIDs) even after the routine vaccinations have been completely effected.6,9,10

The study also showed measles mortality to be slightly higher in boys in contrast to the findings in Europe where data had suggested that measles mortality may be higher in girls by 5%.11 This finding may be due to preferential presentation of a male child for medical attention in this environment as this is an already established culture due to general male preference of the family though, not being statistically significant portends that it is no longer a major occurrence.12,13

Vaccination coverage of measles containing vaccine (MCV) in Nigeria according to WHO/UNICEF is currently put at 62%.5 This study revealed a hospital based coverage rate of less than 20%. This is probably due to the fact that those who asked about their vaccination status were those with measles and not the generality of the patients admitted. The gender similarity in terms of the vaccination status may be due to increased activities of gender equity globally, which is the focus of the third millennium development goal and this is a good development in a country where preferential treatment of male children has been documented in previous studies.12,13

The various reasons given for non-acceptance of vaccination against measles are similar to those for other vaccines at one point or the other, and these have been documented by Health regulatory consultants.14 The measles case fatality ratio of 7.3% from this study is comparable to the findings in Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, where the measles case fatality ratio has been put at 5-10%.6,15 This contrasts sharply with the findings from Osogbo where Adetunji et al. reported a 19% case fatality.16 This may be a reflection of the outlook in a bigger referral hospital with higher utilization, hence more cases of severe measles.

In spite of several efforts at immunizing every eligible child against measles, the overwhelming majority of children managed for measles were not immunized largely due to negative parental disposition to immunization programs in the locality of the study. This is however, likely to be a product of many factors; of which ignorance, or lack of the correct knowledge of vaccination has been documented.14 It therefore becomes imperative to create public awareness on the efficacy of vaccines with regards to the prevention of measles mortality in view of the fact that should vaccinated children develop measles after exposure, they have less severe disease and significantly lower mortality rates.9,10,15

Vaccination programs increase the average age of infection, thereby shifts the burden of disease out of the age group with the highest case fatality-infancy, and young children.

Remarkable progress in reducing measles incidence and mortality has been made in some parts of Sub-Saharan Africa as a consequence of increasing measles vaccine coverage, provision of a second opportunity for measles vaccination through supplementary immunization activities, improved case management, and enhanced surveillance with laboratory confirmation of measles cases.9 These can only be introduced after ignorance or grave misconceptions have been reduced to the barest minimum if not eradicated among the populace. Sustained efforts to maintain high coverage rates of the routine first dose of measles vaccine, coupled with periodic opportunities for a second dose, will achieve the level of herd immunity required to avert the unacceptably high morbidity and mortality rates that result from measles epidemics in susceptible populations.15,17 This is in view of the fact that studies have shown that about four in five children develop protective antibody levels when the measles vaccine is administered at nine months of age, and nearly all have a protective antibody response after vaccination at 12 months of age.18,19 Monthly distribution showed higher frequencies during the dry seasons. This is in keeping with previous observations by earlier studies.1,2,20,21

Conclusion

The hospital based prevalence of measles in Bida was 8.0%, and the case fatality was 7.3%. Most of the children managed for measles did not receive measles vaccination. Four out of five parents/caregiver felt immunization was bad for one reasons or the other. In view of these cases, to further reduce death caused by measles, community approach should be embraced to change the orientation of the parents and the care givers of these children who are not able to make a choice between "to receive" or "not to receive" vaccination for childhood killer diseases, measles inclusive. The lack of immunization and negative parental disposition are the major risks of death among children afflicted by measles.

We recommend that there should be more awareness about the gains of immunization for the children of Bida and their parents should be counseled to always present them for routine immunization and the supplementary immunization while correcting their wrong ideas about the procedure. Female education should also be pursued as a well informed woman will be able to convince the man when the need arises.

Acknowledgements

We thank the parents and the children who willingly took part in the study. Also, special appreciation to Mr. Audu Daudu and Mohammed Naibi both from the Niger state ministry of health. They provided the needed support, took the specimen to the National WHO Measles, Rubella and Yellow fever laboratory in Maitama District Hospital, Abuja and brought the results back. Also, we thank Mr. Suan Thomas, the chief Technologist and the focal person in charge of the laboratory for the cooperation we had from him and other members of staff at the laboratory.

References

- 1.Hart CA, Bennett M, Begon ME. Zoonoses. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999. Sep;53(9):514-515 10.1136/jech.53.9.514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akramuzzaman SM, Cutts FT, Wheeler JG, Hossain MJ. Increased childhood morbidity after measles is short-term in urban Bangladesh. Am J Epidemiol 2000. Apr;151(7):723-735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duke T, Mgone CS. Measles: not just another viral exanthem. Lancet 2003. Mar;361(9359):763-773 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12661-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asaria P, MacMahon E. Measles in the United Kingdom: can we eradicate it by 2010? BMJ 2006. Oct;333(7574):890-895 10.1136/bmj.38989.445845.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO/UNICEF Review of National Immunization Coverage 1980-2008 ;July, 2009:2-10.

- 6.World Health Organization Progress in global measles control and mortality reduction, 2000-2007. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2008. Dec;83(49):441-448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Role and function of the laboratory in measles control and elimination In: Manual for the laboratory diagnosis of measles virus infection December 1999. WHO/V&B/00.16: 14-22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. ELISA tests for measles antibodies: principles and protocols. In: Manual for the laboratory diagnosis of measles virus infection December 1999. WHO/V&B/00.16: 33-38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otten M, Kezaala R, Fall A, Masresha B, Martin R, Cairns L, et al. Public-health impact of accelerated measles control in the WHO African Region 2000-03. Lancet 2005. Sep;366(9488):832-839 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67216-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mbabazi WB, Nanyunja M, Makumbi I, Braka F, Baliraine FN, Kisakye A, et al. Achieving measles control: lessons from the 2002-06 measles control strategy for Uganda. Health Policy Plan 2009. Jul;24(4):261-269 . 10.1093/heapol/czp008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garenne M. Sex differences in measles mortality: a world review. Int J Epidemiol 1994. Jun;23(3):632-642 10.1093/ije/23.3.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yahaya AL. Women empowerment in Nigeria: problems, prospects and implications for counseling. The Counsellor 1999;17(1):132-137 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezeigbo A. Gender issues in Nigeria: a feminine perspective. Lagos: Vista books ltd 1996; 15-20.

- 14.FBA Health System Analysts. State of routine immunization services in Nigeria and reasons for current problems. June 2005: 7-10.<

- 15.Strebel PM, Cochi SL. Waving goodbye to measles. Nature 2001. Dec;414(6865):695-696 10.1038/414695a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adetunji OO, Olusola EP, Ferdinad FF, Olorunyomi OS, Idowu JV, Ademola OG. Measles Among Hospitalized Nigerian Children. The Internet Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatology 2007;7:1-6 [Google Scholar]

- 17.van den Ent M, Gupta SK, Hoekstra E. Two doses of measles vaccine reduce measles dealths. Indian Pediatr 2009. Nov;46(11):933-938 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enquselassie F, Ayele W, Dejene A, Messele T, Abebe A, Cutts FT, et al. Seroepidemiology of measles in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: implications for control through vaccination. Epidemiol Infect 2003. Jun;130(3):507-519 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adu FD, Akinwolere OAO, Tomori 0, Uche LN. Low seroconversion rates to measles vaccine among children in Nigeria. WHO Bulletin 1992; 70 (4): 457 -4 37. 460. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Grais RF, Dubray C, Gerstl S, Guthmann JP, Djibo A, Nargaye KD, et al. Unacceptably high mortality related to measles epidemics in Niger, Nigeria, and Chad. PLoS Med 2007. Jan;4(1):e16.. d 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vaccine preventable deaths and the global immunization vision and strategy, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006. May;55(18):511-515 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]