Abstract

Meprins, metalloproteinases abundantly expressed in the brush-border membranes (BBMs) of rodent proximal kidney tubules, have been implicated in the pathology of renal injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion (IR). Disruption of the meprin β gene and actinonin, a meprin inhibitor, both decrease kidney injury resulting from IR. To date, the in vivo kidney substrates for meprins are unknown. The studies herein implicate villin and actin as meprin substrates. Villin and actin bind to the cytoplasmic tail of meprin β, and both meprin A and B are capable of degrading villin and actin present in kidney proteins as well as purified recombinant forms of these proteins. The products resulting from degradation of villin and actin were unique to each meprin isoform. The meprin B cleavage site in villin was Glu744-Val745. Recombinant forms of rat meprin B and homomeric mouse meprin A had Km values for villin and actin of ∼1 μM (0.6–1.2 μM). The kcat values varied substantially (0.6–128 s−1), resulting in different efficiencies for cleavage, with meprin B having the highest kcat/Km values (128 M−1·s−1 × 106). Following IR, meprins and villin redistributed from the BBM to the cytosol. A 37-kDa actin fragment was detected in protein fractions from wild-type, but not in comparable preparations from meprin knockout mice. The levels of the 37-kDa actin fragment were significantly higher in kidneys subjected to IR. The data establish that meprins interact with and cleave villin and actin, and these cytoskeletal proteins are substrates for meprins.

Keywords: metalloproteinases, cytoskeletal proteins, knockout mice

meprins are metalloproteinases that are highly expressed in epithelial cells of the renal proximal tubules and small intestines. They are composed of two subunits, α and β, that are encoded by distinct genes on human chromosomes 6 and 18, respectively (14, 24, 54). Meprin A is a homooligomer of α-subunits or a heterooligomer of α- and β-subunits, while meprin B is a homooligomer of β-subunits (8, 9, 24, 36). Meprin β has a transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic tail (26 amino acids), with the bulk of the protein being extracellular at the plasma membrane. Meprin α is synthesized with a transmembrane domain, but this subunit is proteolytically cleaved in the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in loss of the transmembrane domain. Consequently, the homomeric forms of meprin A (α/α complexes) are not anchored to the plasma membrane, but rather secreted into the lumen of the kidney tubules and intestines. Meprin B and the heteromeric isoform of meprin A (α/β dimers) are anchored to the plasma membrane through the meprin β-subunit. Expression of meprins has also been demonstrated in the glomeruli of the rat kidney (23), in the skin (7), pancreas, testis, regions of the brain, the liver, heart, and leukocytes (21, 27, 30, 42, 45). Both meprin-α and -β are expressed in various cancer cells including colorectal, breast, pancreatic, and osteosarcoma (37–39). The structure and substrate specificity of the meprin isoforms have been studied extensively in vitro (9, 17). These studies have shown that in addition to isoform-specific substrate preferences, the two meprin subunits have some common substrates (17, 33, 56, 57). Both meprin A and B are capable of proteolytically degrading extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as collagen IV, nidogen-1, laminin, and fibronectin (29, 32, 33, 58), and proteolytically processing bioactive proteins such as gastrin, cholecystokinin, substance P, neurotensin, parathyroid hormone, and chemokines (19, 32, 53, 62). However, cleavage sites for the common substrates are isoform specific. Distinct isoform-specific substrates include the peptide bradykinin (10) for meprin A and orcokinin (10), E-cadherin (27), and prointerleukin-18 (proIL-18) (36) for meprin B. The physiologically relevant meprin substrates have not yet been established.

Changes in the level of expression and localization of the meprin β-subunit have been associated with the pathology of ischemia-reperfusion (IR)-induced kidney injury in mice and rats (16, 18, 55, 58). It has been proposed that in IR-induced acute renal injury, depletion of oxygen and ATP results in accumulation of intracellular sodium, calcium, and reactive oxygen species. These changes are believed to activate various enzyme systems including proteases, resulting in disruption of the brush-border membrane (BBM) cytoskeleton and membrane damage, subsequently leading to necrosis and apoptosis (43). The involvement of proteases has been corroborated by the finding that actinonin, which inhibits meprins selectively, protected against acute renal failure induced by IR in rats (18). In addition, meprin β-deficient mice were shown to have decreased kidney damage following experimental IR (16). The objectives of the current study were to identify in vivo kidney meprin substrates. Data from the present study demonstrate that villin and actin in mouse kidneys interact with and are cleaved by meprins. Both villin and meprin are translocated from the BBM to other cell compartments in IR-induced kidney injury. The data provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying meprin modulation of kidney failure associated with IR-induced injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

This study used 8- to 12-wk-old male mice on a congenic C57BL/6 background. Four genotypes were studied, namely, wild-type (WT) mice that express both meprin α and β, meprin α knockout (KO) mice in which the meprin α gene was disrupted, meprin βKO mice in which the meprin β gene was disrupted, and meprin αβ double KO (meprin null; dKO) mice in which the genes for both meprin-α and meprin β were disrupted (5, 9, 61). The WT mice synthesize all three isoforms of meprin, namely, homomeric meprin A (α-α), heteromeric meprin A (α-β), and meprin B (β-β). The meprin βKO mice synthesize homomeric meprin A. However, because these mice lack meprin β, meprin A is not membrane bound and is secreted into the lumen of proximal tubules. The meprin αKO mice synthesize membrane-bound meprin B. The mice were housed at the Pennsylvania State University, Hershey Medical Center Animal Facility in a 12:12- h light-dark cycle and provided with rat chow and clean drinking water ad libitum. The protocols used were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Kidney protein fractionation.

Mice were euthanized by inhalation of isoflurane, followed by cervical dislocation. Kidneys were excised, decapsulated, weighed, wrapped in aluminum foil, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use. Differential centrifugation was used to fractionate kidney proteins into a soluble/cytosolic-enriched fraction and a BBM-enriched fraction as previously described (30). Briefly, kidneys were homogenized in 9 volumes of ice-cold buffer (2 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.0, with 10 mM mannitol). A 1 M stock of MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mM. and the homogenate stirred at 4°C for 14 min. The homogenate was then centrifuged for 12 min at 1,500 g, and the sediment was discarded. The supernatant fraction was centrifuged for another 12 min at 15,000 g, and the resulting supernatant fluid was saved as the soluble/cytosolic fraction. The resulting sediment was suspended in 5 volumes of buffer and MgCl2 added to a final concentration of 10 mM. This was stirred at 4°C for 15 min and then centrifuged at 2,200 g for 12 min. The supernatant fluid from this centrifugation was transferred to a new tube, which was further centrifuged for 12 min at 15,000 g. The resulting sediment, which is the BBM-enriched fraction, was suspended in an appropriate volume of solubilization buffer. A cocktail of EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), supplemented with 0.1 μM okadoic acid, was added to the tissue homogenization and protein solubilization buffers to prevent degradation of proteins after tissue disruption. Proteins from both fractions were quantified by the Lowry protein assay method, using Bio-Rad's Coomassie Plus protein reagent (Bio-Rad, Santa Cruz, CA).

Affinity precipitation.

To identify proteins that interact with meprins in the mouse kidney, a 26 amino acid biotinylated C-terminal mouse meprin β peptide (YCTRRKYRKKARANTAAMTLENQHAF; Genemed Synthesis, San Francisco, CA) was used. For each reaction, 500 μg of kidney proteins from WT mice were solubilized in membrane solubilization buffer (50 mM Tris, pH7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X-100, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA) with a cocktail of EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics) added to the buffer just before use. The proteins were precleared by incubating with streptavidin beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and mixing on a tube rotator for 30 min at 4°C. They were then centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 g, at 4°C. The supernatant fraction was divided into two halves. The meprin β peptide (2.5 μg) covalently linked to a C-terminal biotin, was added to one half. The other half served as a negative control. To quench nonspecific binding, 10% BSA was added to each reaction. The proteins were incubated on a tube rotator for 2 h at 4°C. Meprin-interacting proteins bound to the streptavidin-agarose beads were collected by centrifugation at 16,000 g. The supernatant fraction containing unbound protein was aspirated. To eliminate nonspecifically bound proteins, the beads were washed three times in buffer 1 (0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.02% sodium azide) and three times in buffer 2 (0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.02% sodium azide), with a final wash in PBS. Proteins bound to the beads were recovered in elution buffer (1% SDS, 100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM DTT). The proteins were electrophoretically separated on 10% acrylamide gels and stained with Sypro Ruby.

In-gel digestion and processing of proteins for mass spectrometry analysis.

Protein bands were excised from gels and stored in 200 μl H2O at −20°C until processed. The gel slices were thawed, destained by incubating in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 60°C for 30 min, and sequentially incubated in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate with 50 and 75% acetonitrile, respectively. The gel slices were dried, and 20 μl of 10 μg/ml trypsin in 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added. These were rehydrated for 1 h at 4°C and then incubated overnight at 37°C. Peptides in the gel plugs were extracted in 50% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at room temperature for 20 min. The extracted peptides were dried using a speed vacuum, suspended in 10 μl of 0.5% TFA, processed through C18 Zip tips, and eluted in 5 μl 0.1% TFA/50% acetonitrile. A total of 1.8 μl of each sample were then spotted on matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-time-of-flight plates (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), layered with 0.5-μl cinnamic acid matrix and subjected to mass spectrometry (MS) analysis.

Induction of ischemia-reperfusion injury.

To investigate the role of meprins in the renal IR response, WT, meprin αKO, meprin βKO, and meprin αβ double KO mice were subjected to IR-induced kidney injury as previously described (16). Mice were injected peritoneally with 50 mg/kg nembutal. Lateral incisions were made on the back, and the renal arteries were clamped bilaterally for 26 min using 2-mm Serrifine vascular clamps (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA). The artery clamps were then removed, and the incisions were sutured. For each genotype, one-half of the mice served as controls which were sham operated without clamping of the renal arteries. Blood samples were collected at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-arterial clamping. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were measured using BUN slides from Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics (Rochester, NY) and read on a Vitros DT60 II Analyzer (Ortho-Diagnostics). The BUN levels were used as an indicator of kidney damage. At 3, 6, 12, and 24 h postclamping, groups of mice were euthanized by exposure to isoflurane. Kidneys were excised, decapsulated, and weighed. For histological analysis, one kidney from each mouse was cut in half longitudinally, fixed in Carnoy's fixative (60% methanol, 30% chloroform, 10% acetic acid) followed by 70% ethanol, and paraffin embedded. The remaining kidney tissue was wrapped in aluminum foil, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until used for proteomic analysis.

Immunohistochemical analysis.

Five-micrometer cross sections of paraffin-embedded kidney tissue were cut on to Superfrost plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Slide sections were deparaffinized through xylene and graded alcohol with a final rinse in water. They were then placed in 80% methanol, 6% H2O2 for 20 min, and washed in H2O for 5 min. They were permeabilized by placing them in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked in PBS containing 10% serum from the species providing the secondary antibody. Kidney sections were then incubated with anti-rabbit polyclonal villin antibody and anti-mouse meprin β antibodies, respectively. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. For confocal microscopy, kidney sections were sequentially incubated with anti-villin and anti-meprin β primary antibodies, followed by Cy2 (green) donkey anti-goat IgG and Cy3 (red) donkey anti-rabbit IgG for villin and meprin B, respectively (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA).

Western blot analysis.

To evaluate the levels of meprin B, villin, and actin proteins in the fractionated kidney protein samples, Western blot analysis was employed. Twenty to 90 μg kidney proteins were subjected to electrophoresis on 8-12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubating in 5% fat-free milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature. Nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C or at room temperature for 1 h. Antibodies used were polyclonal mouse anti-rabbit meprin β diluted 1:5,000; polyclonal goat anti-rabbit villin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) diluted 1:1,000; or monoclonal anti-mouse actin (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted 1:1,000. The blots were washed for 10 min in TBS-T three times, followed by a 1-h RT incubation in secondary antibody diluted 1:4,000 (anti-rabbit IgG for villin and meprin β and anti-mouse IgG for actin). The membranes were washed for 15 min in TBS-T three times, and antigen-antibody complexes were visualized by chemiluminescence following exposure to X-ray film. The intensity of proteins was quantified by densitometry using QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Determination of meprin degradation of villin and actin.

Recombinant forms of homomeric mouse meprin A and rat meprin B were purified from stably transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells and activated by incubating with trypsin in 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, at 37°C for 30 min (meprin A) or 1 h (meprin B). The activation was stopped by adding soy bean trypsin inhibitor (STI). The trypsin and STI were removed by running the reaction mixtures through a Sephadex G25 column. To determine whether villin and actin are meprin substrates, 20 μg of BBM- or 90 μg cytosolic-enriched mouse kidney proteins from meprin-αβ double knockout mice were incubated with 0.12 μM active recombinant homomeric mouse meprin A or recombinant rat meprin B. The proteins were electrophoretically separated on 8–12% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with antibodies against villin and actin using standard Western blot analysis as described above. Initial incubations were done at 37°C for 0–4 h (see Fig. 4). Because nearly complete degradation was observed at 4 h, subsequent incubations were done for 4 h. To establish that degradation was not due to residual trypsin from the activation step, a control solution without meprins (but with equal amounts of trypsin and STI added) was included. This is referred to as activation buffer. Six conditions were included for each of the degradation experiments: 1) a no meprin control, 2) activated meprin A or B, 3) latent meprin A or B, 4) activated meprin A or B preincubated with 20 mM EDTA for 1 h, 5) activated meprin A or B preincubated with 30 μM actinonin for 1 h, and 6) meprin activation buffer. Both EDTA and actinonin are meprin inhibitors.

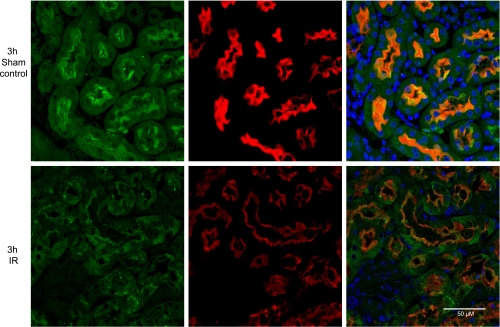

Fig. 4.

Meprins degrade villin. I and II: Western blot analysis of villin in kidney proteins following incubation with meprins. For I, cytosolic-enriched kidney proteins from meprin αβ (double) KO mice were incubated with 1.2 nM active meprin B for 0–4 h. For II, the following incubation conditions were included: Tris buffer alone (lane 1), active meprin B (lane 2), latent meprin B (lane 3), active meprin B preincubated with 20 mM EDTA for 1 h (lane 4), active meprin B preincubated with 30 μM actinonin for 1 h (lane 5), and activation buffer processed with trypsin (lane 6). III and IV: Coomassie-stained gels of purified recombinant human villin incubated with homomeric mouse meprin A (top) or rat meprin B (bottom). For III, villin was incubated with meprin A or B for up to 120 min. For IV, villin was incubated for 4 h under the following conditions: Tris buffer alone (lane 1), active meprins (lane 2), latent meprins (lane 3), active meprins preincubated with 20 mM EDTA for 1 h (lane 4), active meprins preincubated with 30 μM actinonin for 1 h (lane 5), and meprin activation buffer processed with trypsin (lane 6). A: homomeric meprin A. B: meprin B.

To confirm that meprins are capable of directly degrading villin and actin, purified recombinant human villin and purified nonmuscle mouse actin (85% β, 15% γ) were incubated with active meprins with controls as described above. Recombinant villin was purified from BL21 cells transfected with a full-length human villin cDNA (a gift from Dr. Seema Khurana, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN). Purified nonmuscle actin (85% β-actin, 15% γ-actin) was purchased from Cytoskeleton (Denver, CO).

Meprin activity with villin and actin as substrates.

The efficiency of meprin degradation of villin was studied by incubating activated meprin A and meprin B with different concentrations of recombinant human villin and purified nonmuscle actin. For meprin-villin kinetic studies, 12 nM active meprin A or 1.2 nM meprin B was incubated with villin concentrations, ranging from 0.25 to 4.0 μM for 0–10 min. For meprin-actin kinetic studies, 40 nM active meprin A or meprin B was incubated with 0.25–4.0 μM purified nonmuscle actin for 0–10 min. The proteins were separated electrophoretically and stained with Coomassie blue. Optic densitometry (QuantityOne, Bio-Rad) was used to quantify product disappearance over time. Vmax (μM/min) and Km (μM) values were determined using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), by fitting the rate of substrate disappearance against substrate concentration to the Michaelis-Menten equation. The kcat was determined as the ratio of Vmax/[enzyme] per second. These studies initially used full-length villin from which the glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag was cleaved by thrombin. However, this was found to be less stable than the villin with the GST tag still attached. A comparison of the kinetics revealed no difference in using either the thrombin-cleaved villin or the villin with the GST tag still attached. For consistency, the villin with the GST tag was used for the enzyme kinetics data reported in this study.

Determination of meprin cleavage sites on villin.

Meprin cleavage of villin resulted in a stable 83-kDa intermediate product. To determine the location of the meprin cleavage sites on villin, purified recombinant human villin was incubated with activated rat meprin B for 30 min at 37°C. The proteins were separated electrophoretically on 8% polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie blue. Protein bands containing the full-length villin and intermediate villin fragments were cut out, and gel plugs were digested with trypsin for 4 h at 48°C and Glu-C for 18 h at 25°C using the protocols described above. The digested peptides were separated by C18 nanoflow liquid chromatography-MALDI and identified by ProteinPilot software at the Penn State Hershey Core Facility. Peptides identified in the control band but not present in the meprin-cleaved band represent the fragment that is cleaved off by meprin B. Once putative cleavage sites were determined, the size of cleaved products was estimated from the amino acid sequence using ExPASy Proteomic Server tools (www.expasy.ch/cgi-bin/proparam.html) and compared with the size of protein bands observed on acrylamide gels following incubation of villin with active meprin B. Because the data showed that the cleavage site is on the COOH-terminal end of villin, Western blot analysis using a monoclonal anti-GST antibody was included to confirm these data. The GST tag on the recombinant protein is on the N terminal, and so an intermediate villin fragment cleaved on the COOH terminus would have the tag intact; if the site were on the N terminal, then cleavage would lead to release of the GST tag, resulting in a fragment free of the GST tag that cannot be detected on Western blots using the anti-GST antibody.

Statistical analysis.

The data were analyzed by an unpaired Student's t-test for comparisons between two groups. ANOVA was used for comparing three or more groups, with the Bonferroni posttest analysis used for pairwise comparisons. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Villin and actin present in mouse kidney bind to meprin β.

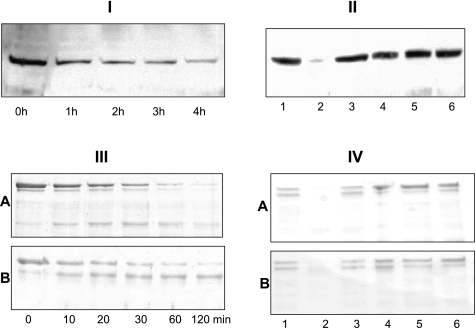

When BBM proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation using a biotinylated meprin β C-terminal peptide, at least 14 protein bands were observed on acrylamide gels stained with Sypro Ruby (Fig. 1A). Most of the protein bands stained faintly and were not identified by MS. However, two of the BBM proteins were identified as villin (band I) and actin (band III). Only one major band was immunoprecipitated from the cytosolic-enriched protein fraction, and it was identified as serum albumin precursor (Fig. 1A, band II). The identities of villin and actin were confirmed by Western blot analysis in which immunoprecipitated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies against villin and actin (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Villin and actin bind to meprin β. A: Sypro Ruby-stained polyacrylamide gel of brush-border membrane (BBM)- and cytosolic-enriched kidney protein fractions immunoprecipitated using a biotinylated meprin β C-terminal peptide. Lanes 1 and 2, immunoprecipitated proteins from the BBM fraction that were incubated with (+) and without (−) the meprin peptide; lanes 3 and 4, proteins immunoprecipitated from the soluble fraction with (+) and without (−) the meprin peptide, respectively. Band I was identified as villin, band II as serum albumin precursor, and band III as actin. B: Western blot for villin and actin. Anti-villin and anti-actin antibodies were used to confirm the identity of the proteins. Lane 1 is a positive control containing 40 μg solubilized kidney proteins; lane 2 is a negative control containing kidney proteins immunoprecipitated without the meprin β peptide; and lane 3 contained proteins immunoprecipitated with the biotinylated meprin β peptide.

Meprin B and villin colocalize in BBM of proximal tubules and are redistributed to the cytosol following ischemic reperfusion-induced kidney injury.

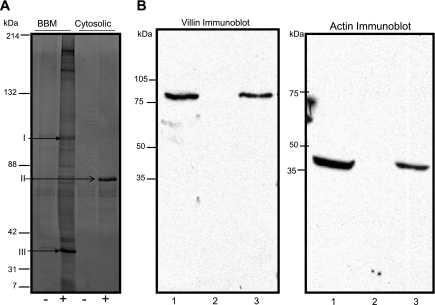

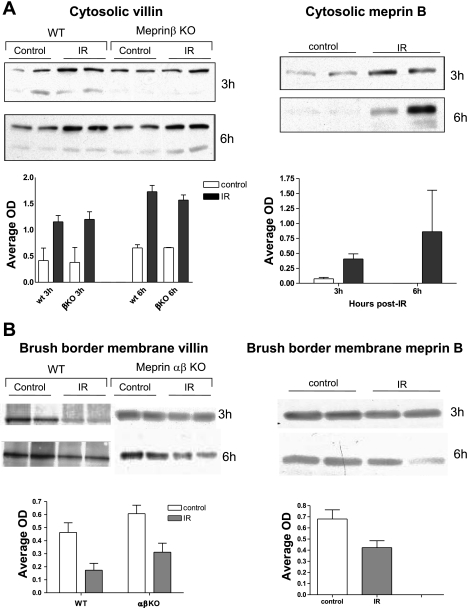

Immunohistological staining coupled with confocal microscopy confirmed that meprin B and villin colocalize to the BBM of kidney sections from sham-operated control mice (Fig. 2). Both villin and meprin B were redistributed from the BBM to the cytosol of epithelial cells at 3 and 6 h post-IR, giving a more diffuse staining pattern. Redistribution of meprin B and villin to the cytosol was confirmed by Western blot analysis, which showed a significant increase (P < 0.05) in the levels of both villin and meprin B in the cytosolic-enriched protein fractions at 3 and 6 h post-IR (Fig. 3A), and a reciprocal decrease in both proteins in the BBM-enriched protein fractions (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 2.

Villin and meprin B colocalize on the BBM and are redistributed to other cell compartments after ischemia-reperfusion (IR). Kidneys from male mice were fixed in Carnoy's fixative and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer slide sections were deparaffinized and probed with antibodies against meprin β and villin. Fluorescent secondary antibodies (Cy2, green, for villin; and Cy3, red, for meprin β) were used to facilitate analysis by confocal microscopy. Hoechst was used to stain the nuclei (blue). In sham-operated control mice, meprin β is exclusively localized in the apical surface (BBM) of proximal tubules. After IR-induced injury, both villin and meprin B are redistributed to other cell compartments.

Fig. 3.

Cytosolic villin and meprin B significantly increase after IR-induced kidney injury (A), and there is a reciprocal decrease in both proteins in the BBM (B). Kidney proteins from wild-type (WT) and meprin knockout mice (KO) subjected to IR-induced injury and sham-operated controls were fractionated into cytosolic- and BBM-enriched fractions. The levels of meprin B (in WT samples) and villin (in WT and meprin KO samples) were quantified by Western blot analysis coupled with optic densitometry using Bio-Rad QuantityOne software. Cytosolic levels of villin and meprin B significantly increased (P < 0.05) in kidneys with IR-induced renal injury compared with kidneys from sham-operated controls at 3 and 6 h post-IR. There was a decrease in the BBM levels for both villin (P < 0.05) and meprin (P < 0.1).

Meprins degrade villin, resulting in isoform-specific villin products.

When proteins from mouse kidneys (BBM- or cytosolic-enriched fractions) were incubated with active meprins and subjected to Western blot analysis, the intensity of the villin band decreased in a time-dependent manner, indicating that meprins degrade villin (Fig. 4I). The degradation was meprin specific and was not observed when the protein samples were incubated with meprin activation buffer, latent meprins, or activated meprins preincubated with two meprin inhibitors, EDTA and actinonin (Fig. 4II). Meprin degradation of villin was confirmed by incubating purified recombinant human villin with activated meprins (Fig. 4, III and IV). When activated recombinant meprins were incubated with purified recombinant human villin, isoform-specific fragments of villin were observed (Fig. 5A). Incubation of villin with active rat meprin B produced an 83-kDa villin fragment that accumulated within 10 min and was stable for over 4 h. Incubation with homomeric mouse meprin A, on the other hand, resulted in a more general degradation with a 53-kDa intermediate product being observed within 30 min, but degraded further upon longer incubations.

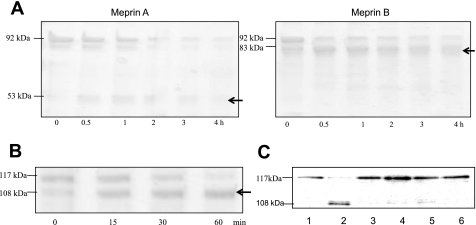

Fig. 5.

Meprins cleave villin to produce isoform-specific products. A: Coomassie blue-stained gel of purified recombinant human villin after incubation with activated meprins A and B for 1–4 h. Recombinant villin from BL21 cells was incubated with thrombin to remove the glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag. The resulting 92-kDa protein was incubated with 12 nM homomeric meprin A or 1.2 nM meprin B and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 8% gels. The dominant fragment for meprin A was 53 kDa, and for meprin B, 83 kDa (see arrows). B: purified recombinant villin with an intact GST tag (∼117 kDa) was incubated with 1.2 nM meprin B for 0–60 min, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue. The dominant villin fragment was 108 kDa. C: Western blot analysis for GST following incubation of full-length villin (with GST tag) with meprin B for 1 h (lane 2). The resulting villin fragment had the GST tag, confirming that the meprin cleavage site is in the COOH terminus of villin. This fragment was not detected in control reactions with PBS (lane 1), latent meprin B (lane 3), active meprins preincubated with 20 mM EDTA for 1 h (lane 4), active meprins preincubated with 30 μM actinonin for 1 h (lane 5), and meprin activation buffer processed with trypsin (lane 6).

Using in-gel trypsin and Glu-C digestion coupled with MS and analysis using Proteus LIMS, the meprin B cleavage site on villin was found to be between Glu744 and Val745 (Fig. 6), which is in the COOH terminus. Using ExPASy Proteomics software (www.expasy.ch/cgi-bin/protparam) the size of the product resulting from cleavage at this site was estimated to be 83.3 kDa, which is in agreement with the product observed on acrylamide gels. To confirm that the meprin B cleavage site is on the COOH terminus, full-length villin with a GST tag on the N terminus was incubated with activated meprin B and either stained with Coomassie or subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-GST antibody. The intermediate villin product was ∼108 kDa compared with the 83-kDa product observed when thrombin-cut villin (without GST tag) was incubated with active meprin B (Fig. 5B). This was further confirmed by Western blot analysis using a monoclonal anti-GST antibody, which showed that when full-length villin with an intact GST tag was incubated with active meprin B, the dominant intermediate product also had an intact GST-tag (Fig. 5C).

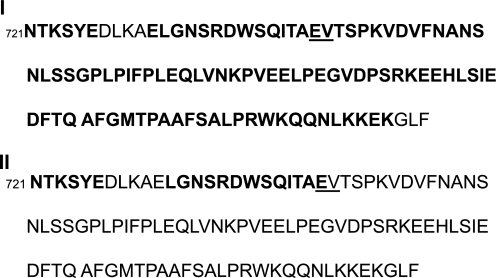

Fig. 6.

Meprin B cleaves villin at a site between Glu744 and Val745 on the COOH terminus. Amino acid sequence of the human villin COOH terminus (107 amino acids) shows the meprin B cleavage site (underlined). Full-length villin was incubated with activated meprin B for 30 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Control sample was incubated without meprin. Protein bands (92 kDa for control and 83 kDa for meprin-cleaved villin) were cut out and in-gel digested with trypsin and Glu-C. Peptides present were separated by C18 nanoflow LC-MALDI and identified using ProteinPilot software. Peptides identified are shown in bold, and the predicted meprin B cleavage site is underlined. I: peptides identified in full-length villin. II: peptides identified in the villin fragment produced when meprin B cleaves full-length villin.

Meprins degrade actin in vitro and in vivo.

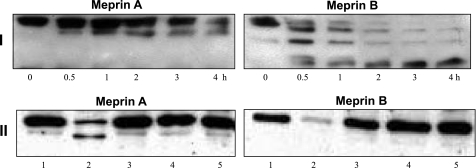

Incubation of cytosolic-enriched proteins from meprin αβ double knockout kidneys (which lack endogenous meprins) with activated meprins resulted in degradation of the actin present in kidney proteins in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 7I). Meprin cleavage of actin present in kidney proteins produced isoform-specific actin fragments. Incubation of kidney proteins with homomeric mouse meprin A cleaved actin to produce a 37-kDa intermediate fragment, while rat meprin B degradation of actin resulted in a 39- and a 35-kDa fragment. The degradation observed was meprin specific and was blocked by preincubation of meprins with EDTA. Furthermore, degradation of actin was not observed when kidney proteins were incubated with latent forms of meprin A or B, or with meprin activation buffer (Fig. 7II). Purified nonmuscle actin (85% actin β, 15% actin γ) was also degraded by meprins A and B, confirming that the degradation of actin is due to meprin activity (Fig. 8). The initial cleavage of cytosolic actin by meprin B was more rapid than for the purified preparation of actin. This could be due to differences in the conformation of actin in the cytosol compared with the purified preparation, its interaction with other proteins, or differences in polymerization.

Fig. 7.

Meprins degrade actin present in kidney proteins. I: Western blots of actin in kidney proteins. Cytosolic-enriched proteins (90 μg) from meprin αβ double KO mice were incubated with 40 nM activated homomeric meprin A or meprin B for 0–4 h. II: cytosolic-enriched kidney proteins from meprin αβ double KO mice were incubated with 40 nM of either meprin A or meprin B for 4 h. The following control reactions were included: Tris buffer (lane 1), activated meprins (lane 2), latent meprins (lane 3), active meprins preincubated with 20 mM EDTA for 1 h (lane 4), and meprin activation buffer processed with trypsin (lane 5). The actin band was only degraded in reactions with activated meprins and was blocked by the meprin inhibitor EDTA.

Fig. 8.

Meprins degrade purified nonmuscle actin. I: Coomassie blue-stained gels of 4 μM purified nonmuscle actin incubated with 40 nM meprin A or B for 0–4 h. II: Coomassie-stained gels of 4 μM purified actin incubated with 40 nM meprin A or B for 4 h with the following controls: Tris buffer (lane 1), activated meprins (lane 2), activated meprins preincubated with 20 mM EDTA (lane 3), latent meprins (lane 4), and meprin activation buffer processed with trypsin (lane 5).

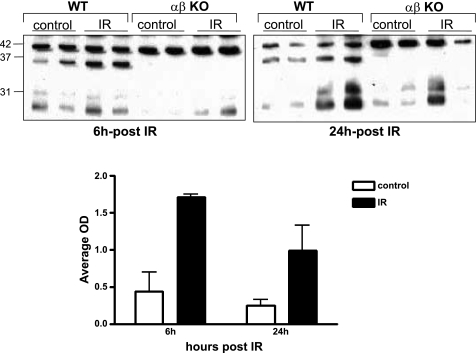

To determine whether meprins play a role in degrading actin in vivo, and whether this degradation plays a role in the pathology of IR-induced kidney injury, Western blot analysis was used to quantify the levels and fragment sizes of soluble actin in cytosolic-enriched kidney protein samples in kidneys subjected to IR and sham-operated controls. Actin levels and fragments in WT and meprin null mice were compared. A 37-kDa actin fragment was detected in cytosolic proteins from WT kidneys (Fig. 9). This fragment was not observed in cytosolic proteins from meprin αKO, meprin βKO, and meprin αβ double KO kidneys. In WT kidneys, the levels of the 37-kDa actin fragment were significantly higher in proteins from kidneys subjected to IR compared with proteins from sham operated controls. The 37-kDa actin fragment was similar in size to the fragment detected when kidney proteins from meprin αβ double KO kidneys were incubated with activated meprin A, suggesting that meprin A plays a role in producing this actin fragment in vivo.

Fig. 9.

Cytosolic levels of a 37-kDa actin fragment increase in kidneys of WT mice subjected to IR. Shown are Western blots of actin in cytosolic-enriched kidney proteins from WT and meprin αβ double KO mice subjected to IR-induced injury and sham-operated controls. In addition to the full-length 42-kDa actin, a 37-kDa actin fragment was detected in kidney proteins from WT mice but not in proteins from meprin αβ double KO mice. The intensity of the 37-kDa actin fragment was significantly higher in WT kidneys subjected to IR-induced injury than in sham-operated controls.

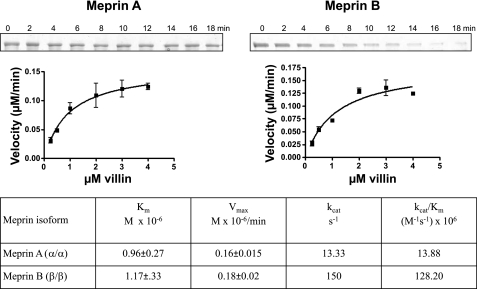

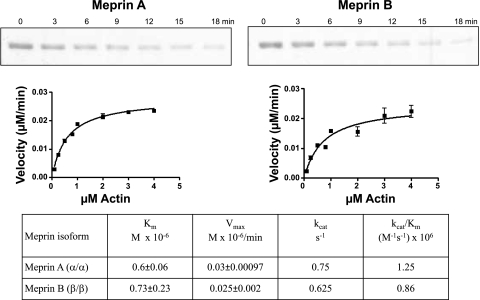

Kinetic analyses demonstrate that both villin and actin are good substrates for meprins.

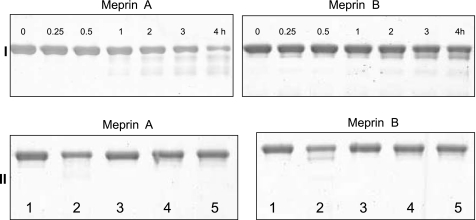

The affinity and efficiency of hydrolysis of villin and actin by meprin A and B were determined by kinetic analyses in vitro (Figs. 10 and 11). The Km values for both substrates were ∼1 μM (varying from 0.6 to 1.17). These values are comparable to the best substrates known for meprins (e.g., the Km pro-IL-18 cleavage by meprin B is 1.3 μM). The efficiencies of hydrolysis (kcat/Km values) are much more variable for villin and actin, the lowest value being 0.86 × 106 for meprin B and actin and the highest 128 × 106 for meprin B and villin. The latter value is among the highest determined thus far for meprin substrates (10, 12, 36).

Fig. 10.

Kinetic parameters for meprin cleavage of purified recombinant human villin. Different concentrations of villin (0.25–4.0 μM) were incubated with 12 nM active homomeric mouse meprin A or 1.2 nM active rat meprin B in 20 mM Tris, 150 nM NaCl, pH 7.5 for 0–10 min. Proteins were electrophoretically separated on 8% acrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie blue, and substrate disappearance was quantified by use of optic densitometry. The rates of product disappearance (μM/min) against substrate concentration (μM) were fitted onto the Michaelis-Menten equation using GraphPad Prism software.

Fig. 11.

Kinetic parameters for meprin cleavage of purified nonmuscle actin. Different concentrations of actin (0.25–4.0 μM) were incubated with 40 nM active homomeric mouse meprin A or 40 nM active rat meprin B in 20 mM Tris, 150 nM NaCl, pH 7.5 for 0–10 min. Proteins were electrophoretically separated on 10% acrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie blue, and substrate disappearance was quantified by use of optic densitometry. The rates of product disappearance (μM/min) against substrate concentration (μM) were fitted onto the Michaelis-Menten equation using GraphPad Prism software.

DISCUSSION

Meprins have been implicated in the pathology of IR-induced kidney failure, a condition that is associated with a high morbidity and mortality. Data from the current study indicate that meprins participate in IR-induced kidney injury in part by cleaving villin and actin, two key components of the proximal tubule BBM cytoskeleton. Previous studies have shown that the localization pattern of meprins is altered in IR injury, with meprins being redistributed from the BBM to the cytoplasm and basolateral membranes of proximal tubule epithelial cells (16, 18, 58). A similar redistribution pattern was observed when kidneys were injected with hypertonic glycerol (55). Mice strains with lower levels of renal meprins have also been reported to develop less renal injury following experimental IR (55). It has recently been shown that mice with targeted disruption of the meprin β gene were significantly protected from renal injury associated with IR (16). Data from the present study provide insights into the mechanism by which meprins enhance damage to the kidney in IR. It has previously been shown that IR-induced kidney injury results in disruption of apical microvilli and the cortical actin microfilament network in proximal tubule cells (40–42). However, the enzyme systems involved in severing of actin filaments and digestion of actin-binding proteins have not been identified, and the mechanisms underlying disruption of the BBM cytoskeleton are not fully understood. The present study identified villin and actin as two functionally related kidney proteins that bind to the carboxyl-terminal tail of meprin β. This study further showed that actin and villin are both degraded by meprins in vivo and in vitro. This degradation may be partly responsible for the disruption of proximal tubule BBM observed in IR.

Villin is an epithelial cell-specific protein that belongs to a family of actin-binding proteins. Expression of villin is restricted to epithelial cells from the gastrointestinal, the urogenital, and respiratory tracts, where it binds to and bundles actin in brush-border microvilli (50). Villin is required for the assembly of microvilli at the apical membranes of cells in developing proximal tubules and intestines (11, 22, 25, 26, 52). Villin has the unique property of being able to nucleate, sever, cap, and cross-link actin in a calcium- and phosphorylation-regulated manner (44, 63). Additionally, it binds to phosphoinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) (28) and interacts with PLCγ (46), making it a potential signaling intermediate between surface receptors and the cytoskeleton. After renal tubular cell injury, brush-border fragments are shed into the tubular lumen and excreted in urine, and villin excreted in urine is a possible marker for early detection of tubular damage in the human kidney (65). Villin was also internalized in proximal tubule epithelial cells in rats intoxicated with the heavy metal cadmium (51). It has recently been shown that the presence of villin protects intestinal cells from apoptosis, and villin-deficient mice were predisposed to higher levels of apoptosis and a more severe form of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis (59). By degrading villin, meprins may thus predispose proximal tubule epithelial cells to apoptosis. Actin, a cytoskeletal protein found in many cell types, is important for the structural integrity of the villi that make up the BBM of kidney proximal tubules and small intestines. Both ischemia (in vivo) and ATP depletion (in vitro) have been shown to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton and associated membrane structures. In kidney tubules, the redistribution of actin from the apical pole to the cytoplasm is followed by disruption of cellular junctions (e.g., zonula occludens), leading to increases in cellular permeability and subsequent loss of gate function (20, 47, 48). Epithelial cells in the S3 segment of proximal kidney tubules (where meprins are highly expressed) have been shown to have increased sensitivity to ischemia compared with the medullary thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and the distal tubule cells (which lack meprins) with respect to morphological, biochemical, and functional derangements (60). The present study confirmed the redistribution of both villin and meprin B by confocal microscopy and Western blot analysis, which showed a significant increase in the cytosolic levels of both proteins. Although a previous study by Brown et al. (15) showed no change in total villin levels following IR, that study did not quantify villin in different cell compartments as in the present study. Rather than an increase in total villin levels per se, the redistribution of villin from the BBM to the cytosol appears be of greater significance in the pathology of IR injury. Previous studies have shown that normal actin distribution in the brush border is accompanied by villin migration back to the apical domain IR (40–42). The current in vitro studies with purified recombinant human villin, purified nonmuscle actin, and proteins extracted from meprin KO mouse kidneys demonstrate that degradation of villin and actin present in kidney is partly due to direct meprin activity, rather than a downstream effect of other proteases present in the kidneys.

In vitro meprin substrates have been extensively studied. However, very little is known about the in vivo kidney substrates. Previously documented meprin substrates include ECM proteins such as collagen IV, nidogen-1, laminin, and fibronectin (29, 32, 33, 58); bioactive proteins such as gastrin, cholecystokinin, bradykinin, substance P, neurotensin, neuropeptide Y, glucagon, secretin, valosin, orcokinin, kinetensin, azocasein, and parathyroid hormone (10, 19, 32, 53, 62); and proinflammatory cytokines such as pro-IL-18 (4). Using a protease proteomic approach coupled with MS, Ambort et al. (1) identified 22 human meprin substrates in a Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cell system. These included proteins from 6 different functional clusters: 10 in cell growth and/or maintenance, 4 in immune response, 2 in transport, 2 proteins in cell communicating/signal transduction, 2 in metabolism/energy pathways, and 2 in protein metabolism. Kinetic studies have been done for some of these meprin substrates. Meprin-azocasein degradation, with a kcat/Km ratio of 231 M−1·s−1 × 106 (12) is to date the substrate most efficiently cleaved by homomeric meprin A. Villin, with a kcat/Km ratio of 13.88 M−1·s−1 × 106, ranks second. The kcat/Km value for meprin B degradation of villin (128 M−1·s−1 × 106) is higher than for other meprin B substrates studied to date (4, 10, 12). Before the present studies, gastrin, with a kcat/Km value of 17.5 M−1·s−1 × 106, had the highest enzyme specificity constant documented (10). Data from the present study show that both villin and actin are very good meprin substrates, and that meprin B cleaves villin more efficiently than homomeric meprin A.

The cleavage products are also isoform specific, with meprin B cleaving villin between Glu744 and Val745 to initially produce a 83-kDa fragment, which is subsequently degraded. Homomeric meprin A, on the other hand, appears to have a more general degradation, with a 53-kDa intermediate product that is not very stable. The meprin B cleavage site on villin removes 83 amino acid residues on the COOH-terminal region of villin. This sequence comprises the villin head piece, which contains the Ca2+-independent actin binding site (2, 31) and includes a conserved KKEK motif which is essential for its morphogenic activity in cell culture (13). The cleaved sequence also includes one of the PIP2 binding sites, PIP5, between amino acids 816–824; (31). This implies that meprin B cleavage of villin disrupts the structural organization of the brush-border cytoskeleton by removing this critical actin binding site and PIP2 regulation site, potentially decreasing villin's ability to bundle actin. Accordingly, meprin B, which is cell associated, appears to be the key isoform in injury resulting from IR. Meprin B cleavage of villin leaves all the tyrosine phosphorylation sites implicated in inhibiting the ability of villin to bind to actin intact (64). Data from the current study also demonstrate that meprins are responsible for cleavage of actin to produce the 37-kDa fragment observed in cytosolic-enriched kidney proteins from WT kidneys. This fragment was not observed in kidney proteins from meprin-null mice (αKO, βKO, and αβKO), leading us to conclude that the cell-bound meprin α-subunit is required for its production in vivo. Another protein that could play a role in IR is OS-9. OS-9 has been shown to interact with the carboxyl-terminal tail of meprin β (34). More importantly, OS-9 has been shown to interact with the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) (3), a protein which mediates the cell's response to changes in oxygen concentration. However, it has not been determined if OS-9 is a meprin substrate and whether this interaction with meprin is significant in vivo.

There is growing evidence for involvement of meprins in digestive, immunological, and other kidney diseases. Several studies have demonstrated a role for meprins in inflammatory processes (4, 21, 35). In mice, meprin β was detected in cortical and medullary macrophages of the lymph node, and deletion of the β gene decreased the ability of leukocytes to migrate through Matrigel (21). In the small intestines, meprins were found in the leukocytes of the lamina propria, with levels being elevated in inflammatory conditions (35). Additionally, meprins cleave the precursor of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-18 in vitro, resulting in a biologically active IL-18 fragment capable of activating NF-κB in EL-4 cells (4). Meprin α has also been shown to be a susceptibility gene in human and mouse inflammatory bowel disease (5). Four single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the coding region of meprin A and one SNP in the 3′-untranslated region of meprin α had a strong association with human ulcerative colitis, and mice in which the meprin α gene was disrupted showed a more severe form of colitis induced by oral administration of DSS compared with WT mice. Meprins may also compromise the permeability of epithelial cells by degrading proteins that form tight junctions between the cells. Meprin B has been shown to cleave E-cadherin (27) and occludin (Bao J and Bond JS, unpublished observations), resulting in a weakened intercellular adhesion. Meprin β gene polymorphisms have also been associated with diabetic nephropathy among the Pima Indians, a group with an extremely high incidence of type II diabetes and an incidence of end-stage renal disease that is 23 times that of the general US population (49). When streptozotocin was used to induce type 1 diabetes in rats, urinary meprin A excretion was increased and BBM meprin A levels and activity were decreased (6).

The present data provide a mechanism for disruption of the cytoskeleton of the BBM of kidney tubular cells via proteolysis of cytoskeletal proteins. This is the first study to show that villin and actin are meprin substrates. Taken together, our data suggest that in IR, damage to the kidney proximal tubules is in part due to direct degradation/cleaving of cytoskeletal villin and actin by meprins. Because villin and actin are critical in the assembly and maintenance of the BBM cytoskeleton, this degradation/cleaving compromises the integrity of the BBM cytoskeleton. This knowledge should help in development of therapies that downregulate or inhibit meprins and thereby minimize damage to kidneys in IR that occurs during kidney transplant and other disease conditions associated with renal IR.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK19691 to J. S. Bond.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Seema Khurana (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN) for the gift of the villin cDNA construct used to produce recombinant human villin. Many thanks also to Drs. Gaylen Bradley and John Bylander (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Penn State University College of Medicine) for advice and critique of the manuscript.

Present address of E. M. Ongeri: Dept. of Biology, North Carolina A&T State Univ., 1601 E. Market St., Greensboro, NC 27411 (e-mail: eongeri@ncat.edu).

Present address of O. Anyanwu: Lincoln University, 1570 Baltimore Pike, Lincoln University, PA 19252.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ambort D, Stalder D, Lottaz D, Huguenin M, Oneda B, Heller M, Sterchi EE. A novel 2D-based approach to the discovery of candidate substrates for the metalloendopeptidase meprin. FEBS J 275: 4490–4509, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Athman R, Louvard D, Robine S. The epithelial cell cytoskeleton and intracellular trafficking. III. How is villin involved in the actin cytoskeleton dynamics in intestinal cells? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283: G496–G502, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baek JH, Mahon PC, Oh J, Kelly B, Krishnamachary B, Pearson M, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, Semenza GL. OS-9 interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and prolyl hydroxylases to promote oxygen-dependent degradation of HIF-1alpha. Mol Cell 17: 503–512, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banerjee S, Bond JS. Prointerleukin-18 is activated by meprin beta in vitro and in vivo in intestinal inflammation. J Biol Chem 283: 31371–31377, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banerjee S, Oneda B, Yap LM, Jewell DP, Matters GL, Fitzpatrick LR, Seibold F, Sterchi EE, Ahmad T, Lottaz D, Bond JS. MEP1A allele for meprin A metalloprotease is a susceptibility gene for inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol 2: 220–231, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bankus JM, Bond JS. Expression and distribution of meprin protease subunits in mouse intestine. Arch Biochem Biophys 331: 87–94, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Becker-Pauly C, Howel M, Walker T, Vlad A, Aufenvenne K, Oji V, Lottaz D, Sterchi EE, Debela M, Magdolen V, Traupe H, Stocker W. The alpha and beta subunits of the metalloprotease meprin are expressed in separate layers of human epidermis, revealing different functions in keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation. J Invest Dermatol 127: 1115–1125, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bertenshaw GP, Norcum MT, Bond JS. Structure of homo- and hetero-oligomeric meprin metalloproteases. Dimers, tetramers, and high molecular mass multimers. J Biol Chem 278: 2522–2532, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bertenshaw GP, Turk BE, Hubbard SJ, Matters GL, Bylander JE, Crisman JM, Cantley LC, Bond JS. Marked differences between metalloproteases meprin A and B in substrate and peptide bond specificity. J Biol Chem 276: 13248–13255, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bertenshaw GP, Villa JP, Hengst JA, Bond JS. Probing the active sites and mechanisms of rat metalloproteases meprin A and B. Biol Chem 383: 1175–1183, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biemesderfer D, Dekan G, Aronson PS, Farquhar MG. Assembly of distinctive coated pit and microvillar microdomains in the renal brush border. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 262: F55–F67, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bond JS, Beynon RJ. Meprin: a membrane-bound metallo-endopeptidase. Curr Top Cell Regul 28: 263–290, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bond JS, Butler PE, Beynon RJ. Metalloendopeptidases of the mouse kidney brush border: meprin and endopeptidase-24.11. Biomed Biochim Acta 45: 1515–1521, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bond JS, Rojas K, Overhauser J, Zoghbi HY, Jiang W. The structural genes, MEP1A and MEP1B, for the alpha and beta subunits of the metalloendopeptidase meprin map to human chromosomes 6p and 18q, respectively. Genomics 25: 300–303, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown D, Lee R, Bonventre JV. Redistribution of villin to proximal tubule basolateral membranes after ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273: F1003–F1012, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bylander J, Li Q, Ramesh G, Zhang B, Reeves WB, Bond JS. Targeted disruption of the meprin metalloproteinase beta gene protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F480–F490, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bylander JE, Bertenshaw GP, Matters GL, Hubbard SJ, Bond JS. Human and mouse homo-oligomeric meprin A metalloendopeptidase: substrate and inhibitor specificities. Biol Chem 388: 1163–1172, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carmago S, Shah SV, Walker PD. Meprin, a brush-border enzyme, plays an important role in hypoxic/ischemic acute renal tubular injury in rats. Kidney Int 61: 959–966, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chestukhin A, Litovchick L, Muradov K, Batkin M, Shaltiel S. Unveiling the substrate specificity of meprin beta on the basis of the site in protein kinase A cleaved by the kinase splitting membranal proteinase. J Biol Chem 272: 3153–3160, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Craig SS, Reckelhoff JF, Bond JS. Distribution of meprin in kidneys from mice with high- and low-meprin activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 253: C535–C540, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crisman JM, Zhang B, Norman LP, Bond JS. Deletion of the mouse meprin beta metalloprotease gene diminishes the ability of leukocytes to disseminate through extracellular matrix. J Immunol 172: 4510–4519, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dudouet B, Robine S, Huet C, Sahuquillo-Merino C, Blair L, Coudrier E, Louvard D. Changes in villin synthesis and subcellular distribution during intestinal differentiation of HT29–18 clones. J Cell Biol 105: 359–369, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Friederich E, Vancompernolle K, Huet C, Goethals M, Finidori J, Vandekerckhove J, Louvard D. An actin-binding site containing a conserved motif of charged amino acid residues is essential for the morphogenic effect of villin. Cell 70: 81–92, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gorbea CM, Marchand P, Jiang W, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Bond JS. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of the mouse meprin beta subunit. J Biol Chem 268: 21035–21043, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grone HJ, Weber K, Helmchen U, Osborn M. Villin—a marker of brush border differentiation and cellular origin in human renal cell carcinoma. Am J Pathol 124: 294–302, 1986 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heintzelman MB, Mooseker MS. Assembly of the brush border cytoskeleton: changes in the distribution of microvillar core proteins during enterocyte differentiation in adult chicken intestine. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 15: 12–22, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huguenin MME, Traschsel-Rosmann Oneda B, Ambort D, Sterchi EE, Lottaz D. The metalloprotease meprin β processes E-cadherin and weakens intercellular adhesion. PLoS One 3: e2153, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Janmey PA, Iida K, Yin HL, Stossel TP. Polyphosphoinositide micelles and polyphosphoinositide-containing vesicles dissociate endogenous gelsolin-actin complexes and promote actin assembly from the fast-growing end of actin filaments blocked by gelsolin. J Biol Chem 262: 12228–12236, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaushal GP, Walker PD, Shah SV. An old enzyme with a new function: purification and characterization of a distinct matrix-degrading metalloproteinase in rat kidney cortex and its identification as meprin. J Cell Biol 126: 1319–1327, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kenny AJ, Ingram J. Proteins of the kidney microvillar membrane. Purification and properties of the phosphoramidon-insensitive endopeptidase ('endopeptidase-2') from rat kidney. Biochem J 245: 515–524, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khurana S, George SP. Regulation of cell structure and function by actin-binding proteins: Villin's perspective. FEBS Lett 582: 2128–2139, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kohler D, Kruse M, Stocker W, Sterchi EE. Heterologously overexpressed, affinity-purified human meprin alpha is functionally active and cleaves components of the basement membrane in vitro. FEBS Lett 465: 2–7, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kruse MN, Becker C, Lottaz D, Kohler D, Yiallouros I, Krell HW, Sterchi EE, Stocker W. Human meprin alpha and beta homo-oligomers: cleavage of basement membrane proteins and sensitivity to metalloprotease inhibitors. Biochem J 378: 383–389, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Litovchick L, Friedmann E, Shaltiel S. A selective interaction between OS-9 and the carboxyl-terminal tail of meprin beta. J Biol Chem 277: 34413–34423, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lottaz D, Buri C, Monteleone G, Rosmann S, Macdonald TT, Sanderson IR, Sterchi EE. Compartmentalised expression of meprin in small intestinal mucosa: enhanced expression in lamina propria in coeliac disease. Biol Chem 388: 337–341, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marchand P, Tang J, Bond JS. Membrane association and oligomeric organization of the alpha and beta subunits of mouse meprin A. J Biol Chem 269: 15388–15393, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matters GL, Bond JS. Expression and regulation of the meprin beta gene in human cancer cells. Mol Carcinog 25: 169–178, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matters GL, Bond JS. Meprin B: transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of the meprin beta metalloproteinase subunit in human and mouse cancer cells. APMIS 107: 19–27, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Matters GL, Manni A, Bond JS. Inhibitors of polyamine biosynthesis decrease the expression of the metalloproteases meprin alpha and MMP-7 in hormone-independent human breast cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis 22: 331–339, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Molitoris BA. Ischemia-induced loss of epithelial polarity: potential role of the actin cytoskeleton. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F769–F778, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Molitoris BA, Dahl R, Geerdes A. Cytoskeleton disruption and apical redistribution of proximal tubule Na+-K+-ATPase during ischemia. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F488–F495, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Molitoris BA, Dahl R, Geerdes A. Role of the actin cytoskeleton in ischemic injury. Chest 101: 52S–53S, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Molitoris BA, Leiser J, Wagner MC. Role of the actin cytoskeleton in ischemia-induced cell injury and repair. Pediatr Nephrol 11: 761–767, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Northrop J, Weber A, Mooseker MS, Franzini-Armstrong C, Bishop MF, Dubyak GR, Tucker M, Walsh TP. Different calcium dependence of the capping and cutting activities of villin. J Biol Chem 261: 9274–9281, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oneda B, Lods N, Lottaz D, Becker-Pauly C, Stocker W, Pippin J, Huguenin M, Ambort D, Marti HP, Sterchi EE. Metalloprotease meprin beta in rat kidney: glomerular localization and differential expression in glomerulonephritis. PLoS One 3: e2278, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Panebra A, Ma SX, Zhai LW, Wang XT, Rhee SG, Khurana S. Regulation of phospholipase C-γ1 by the actin-regulatory protein villin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1046–C1058, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reckelhoff JF, Butler PE, Bond JS, Beynon RJ, Passmore HC. Mep-1, the gene regulating meprin activity, maps between Pgk-2 and Ce-2 on mouse chromosome 17. Immunogenetics 27: 298–300, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reckelhoff JF, Craig SS, Beynon RJ, Bond JS. Meprin phenotype and cyclosporin A toxicity in mice. Adv Exp Med Biol 240: 293–304, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Red Eagle AR, Hanson RL, Jiang W, Han X, Matters GL, Imperatore G, Knowler WC, Bond JS. Meprin beta metalloprotease gene polymorphisms associated with diabetic nephropathy in the Pima Indians. Hum Genet 118: 12–22, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rodman JS, Mooseker M, Farquhar MG. Cytoskeletal proteins of the rat kidney proximal tubule brush border. Eur J Cell Biol 42: 319–327, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sabolic I, Herak-Kramberger CM, Brown D. Subchronic cadmium treatment affects the abundance and arrangement of cytoskeletal proteins in rat renal proximal tubule cells. Toxicology 165: 205–216, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shibayama T, Carboni JM, Mooseker MS. Assembly of the intestinal brush border: appearance and redistribution of microvillar core proteins in developing chick enterocytes. J Cell Biol 105: 335–344, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sterchi EE, Naim HY, Lentze MJ, Hauri HP, Fransen JA. N-benzoyl-l-tyrosyl-p-aminobenzoic acid hydrolase: a metalloendopeptidase of the human intestinal microvillus membrane which degrades biologically active peptides. Arch Biochem Biophys 265: 105–118, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sterchi EE, Stocker W, Bond JS. Meprins, membrane-bound and secreted astacin metalloproteinases. Mol Aspects Med 29: 309–328, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Trachtman H, Valderrama E, Dietrich JM, Bond JS. The role of meprin A in the pathogenesis of acute renal failure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 208: 498–505, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Villa JP, Bertenshaw GP, Bond JS. Critical amino acids in the active site of meprin metalloproteinases for substrate and peptide bond specificity. J Biol Chem 278: 42545–42550, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Villa JP, Bertenshaw GP, Bylander JE, Bond JS. Meprin proteolytic complexes at the cell surface and in extracellular spaces. Biochem Soc Symp: 53–63, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Walker PD, Kaushal GP, Shah SV. Meprin A, the major matrix degrading enzyme in renal tubules, produces a novel nidogen fragment in vitro and in vivo. Kidney Int 53: 1673–1680, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang Y, Tomar A, George SP, Khurana S. Obligatory role for phospholipase C-γ1 in villin-induced epithelial cell migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C1775–C1786, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weinberg JM, Buchanan DN, Davis JA, Abarzua M. Metabolic aspects of protection by glycine against hypoxic injury to isolated proximal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 949–958, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wolz RL, Harris RB, Bond JS. Mapping the active site of meprin-A with peptide substrates and inhibitors. Biochemistry 30: 8488–8493, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yamaguchi T, Fukase M, Sugimoto T, Kido H, Chihara K. Purification of meprin from human kidney and its role in parathyroid hormone degradation. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 375: 821–824, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhai L, Kumar N, Panebra A, Zhao P, Parrill AL, Khurana S. Regulation of actin dynamics by tyrosine phosphorylation: identification of tyrosine phosphorylation sites within the actin-severing domain of villin. Biochemistry 41: 11750–11760, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhai L, Zhao P, Panebra A, Guerrerio AL, Khurana S. Tyrosine phosphorylation of villin regulates the organization of the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 276: 36163–36167, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zimmerhackl LB, Leuk B, Hoschutzky H. The cytoskeletal protein villin as a parameter for early detection of tubular damage in the human kidney. J Chromatogr 587: 81–84, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]