Abstract

d-Aspartate (d-Asp) activates an excitatory current in neurons of Aplysia californica. Although d-Asp is presumed to activate a subset of l-glutamate (l-Glu) channels, the identities of putative d-Asp receptors and channels are unclear. Whole cell voltage- and current-clamp studies using primary cultures of Aplysia buccal S cluster (BSC) neurons were executed to characterize d-Asp-activated ion channels. Both d-Asp and l-Glu evoked currents with similar current-voltage relationships, amplitudes, and relatively slow time courses of activation and inactivation when agonists were pressure applied. d-Asp-induced currents, however, were faster and desensitized longer, requiring 40 s to return to full amplitude. Of cells exposed to both agonists, 25% had d-Asp- but not l-Glu-induced currents, suggesting a receptor for d-Asp that was independent of l-Glu receptors. d-Asp channels were permeable to Na+ and K+, but not Ca2+, and were vulnerable to voltage-dependent Mg2+ block similarly to vertebrate NMDA receptor (NMDAR) channels. d-Asp may activate both NMDARs and non-l-Glu receptors in the nervous system of Aplysia.

Keywords: invertebrate, cation channel, reversal potential, buccal ganglion, N-methyl-d-aspartate

in the 1960s, d-aspartate (d-Asp) was discovered to have physiological actions in neurons (Curtis and Watkins 1963; Davies and Johnston 1976), but it was not until decades later with the discovery of free d-amino acids in the tissues of several organisms that the relevance of these compounds was understood (reviewed in D'Aniello 2007; Fuchs et al. 2005). Whereas d-serine (d-Ser) has been the subject of much research regarding its role in the nervous system, acting as an agonist at the glycine binding site of NMDA receptors (NMDARs), there have been comparatively few studies of the role of d-Asp. d-Asp undergoes a transient increase in concentration in the central nervous system (CNS) during embryonic development in vertebrates, and then these levels rapidly decrease postnatally due to a rise in the concentration of d-aspartate oxidase (Furuchi and Homma 2005). Although there has been considerable research on an endocrine role for d-Asp (D'Aniello 2007), there has been less exploration of a possible neurotransmitter or neuromodulatory role, despite its presence and the machinery for its synthesis, release, uptake, and breakdown in nervous tissue of a variety of organisms (D'Aniello 2007; Homma 2007; Kim et al. 2010; Savage et al. 2001; Scanlan et al. 2010; Waagepetersen et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2011; Wolosker et al. 2000; Yamada et al. 2006) and in neuronal processes of Aplysia (Miao et al. 2005; Spinelli et al. 2006). Yet to be demonstrated is the physiological and molecular description of the ion channels activated by d-Asp.

Owing to their structural similarity, d-Asp and l-Glu both purportedly activate ionotropic glutamate receptors (Huang et al. 2005; Kiskin et al. 1990; Olverman et al. 1988). l-Glu-activated ion channels include subtypes activated by NMDA, AMPA, and kainate. The majority of evidence gathered so far would suggest that d-Asp is a ligand for NMDARs (Kiskin et al. 1990; Olverman et al. 1988). Errico et al. (2008a, 2008b; in press) found that d-Asp activated currents via NR2A–D receptor subunits and increased long-term potentiation through NMDAR activity, yet it also activated currents independently of NMDARs, suggesting a unique d-Asp receptor. Meanwhile, Huang et al. (2005) found that d-Asp did not activate AMPA/kainate or metabotropic glutamate receptors.

Miao et al. (2006) investigated the electrophysiological responses to d-Asp in Aplysia neurons of the abdominal and cerebral ganglia. They found that d-Asp induced depolarizations similarly to l-Glu; however, in some neurons d-Asp responses had opposite polarity from l-Glu responses, similarly suggesting that d-Asp may have actions independent of l-Glu and its target receptors.

The identified cells and cell clusters of Aplysia californica provide a useful system for the study of d-Asp. Numerous studies have confirmed the widespread presence of d-Asp in each of the ganglia of the Aplysia CNS in multiple species such as A. fasciata (D'Aniello et al. 1993), A. limacina (Spinelli et al. 2006), and A. californica (Liu et al. 1998; Miao et al. 2005, 2006). l-Glu receptors are found throughout the Aplysia nervous system, including the well-studied NMDA- (Ha et al. 2006) and AMPA-type receptors that activate channels (Antzoulatos and Byrne 2004), as well as the invertebrate-specific l- Glu-activated Cl− channels (King and Carpenter 1989). In addition, d-Asp current responses in Aplysia have been shown to undergo changes associated with aging (Fieber et al. 2010) and are subject to modulation by 5-HT similarly to AMPA receptors (Carlson and Fieber, in press), suggesting this endogenous compound may play an important physiological role. The goal of this study was to provide an electrophysiological characterization of d-Asp-activated currents in S cluster neurons of the buccal ganglion (BSC), describing the electrophysiological properties of d-Asp current responses and comparisons to l-Glu-activated currents. BSC cells show a relatively high preponderance of responses to d-Asp and are innervated (Jahan-Parwar and Fredman 1976) by neurons believed to contain d-Asp due to high d-Asp racemase immunoreactivity (Scanlan et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2011).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

California sea hares, A. californica (∼300–500 g; ∼6–8 mo of age and sexually immature with no evidence of mating and no egg masses in the cages), were obtained from the University of Miami National Institutes of Health National Resource for Aplysia (Miami, FL). Primary cultures of BSC cells were prepared according to the methods described by Fieber (2000). Animals were anesthetized for 1 h in a 1:1 mixture of seawater from the culture facility and 0.366 M MgCl2. Ganglia were then dissected out, and each was placed in a 5-ml solution containing 18.75 mg of dispase (Boehringer Mannheim 10165859001), 5 mg of hyaluronidase (Sigma H4272), and 1.5 mg of collagenase type XI (Sigma C9407) in artificial seawater (ASW) and placed on a shaker set to low speed for ∼24 h at room temperature (∼22°C). Cells from specific ganglia or areas of ganglia were then dissociated onto 35-mm diameter polystyrene culture plates (Becton Dickinson, Falcon Lakes, NJ) that were coated with poly-d-lysine (MP Biomedicals IC15017525) at 0.2 mg/ml sterile water for 25 min and then rinsed twice in sterile water, dried, and UV-sterilized before use. Cells were stored at 17°C until used in experiments 24 h later.

Electrophysiology.

Whole cell voltage-clamp and current-clamp measurements were made with glass patch electrodes pulled from thick-walled 1.5-mm- diameter borosilicate glass capillaries using a Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Voltage and current data were collected, and whole cell capacitance and series resistance compensations were made using an Axopatch 200B clamp amplifier with a capacitance compensation range of 1–1,000 pF, connected to a personal computer and Digidata 1200 analog-to-digital converter using pClamp software to record data and issue voltage and current commands (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Bath solutions were flowed onto cells during recording via a 6-bore gravity-fed perfusion system that dispensed solutions from 1-μl micropipettes ∼200 μm away from the cell. The environment around the cell was adjusted to a new solution within 500 ms of switching on the flow of the relevant gravity pipette. Solutions containing agonist were briefly applied to the cell via a micropipette attached to a picospritzer powered by N2 adjustable for pressure and duration (Parker Hannifin, Cleveland, OH). The picospritzer pipette tip was aimed at the cell and positioned at an angle of ∼45° from the perfusion flow but closer to the cell, ∼ 30 μm from the cell body. Unless otherwise noted, in all experiments d-Asp was applied via the picospritzer for 100 ms at a concentration of 1 mM. The effective concentration of agonist was estimated to reach the cell surface <25 ms after the start of the 100-ms pulse of agonist. Dye-loading experiments indicated that mixing of agonist with the gravity-fed bath solution was minimal for the duration of the picospritzer pulse due to the proximity of the picospritzer pipette to the cell and the relatively high force of the picospritzer pulse compared with the bath solution. To avoid desensitization, ∼1–2 min were allowed between applications of d-Asp to individual cells.

To determine the time constants of activation and inactivation, whole cell currents from five cells with comparable current amplitudes were fit using a double-exponential Simplex/SSE algorithm (Axograph). Time constants for these fits were averaged (±SD) across cells.

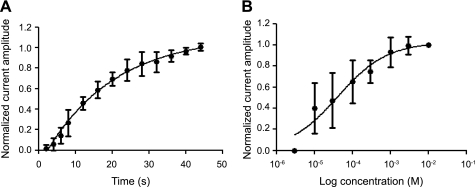

Desensitization experiments were performed using a two-pulse protocol with the interpulse interval varied from 2 to 44 s. Current amplitude of the second pulse was expressed as a fraction of the initial current. The plot of the normalized average current amplitude as a function of the interpulse duration was fitted using a single-exponential equation: It = [Imax − (Imax − I0)exp(−t/τ)], where It is the current at time t, Imax is the current amplitude at infinite time, I0 is the current at time 0 (directly after the first pulse), and τ is the time constant.

Dose-response data were expressed as a fraction of the current amplitude in response to 10 mM d-Asp. Data were fit using the equation I = Imax/[1 + (EC50/[agonist])nH], where nH is the Hill slope coefficient (Verdoorn and Dingledine 1988). Curves and graphs for desensitization and dose-response data were plotted using GraphPad Prism (version 5.03; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Solutions.

All reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Extracellular solution (ECS) normally consisted of ASW containing (in mM) 417 NaCl, 10 KCl, 10 CaCl2(2H2O), 55 MgCl2(6H2O), and 15 HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.6 (∼physiological pH; unpublished observations). Control intracellular solutions (ICS) contained (in mM) 458 KCl, 2.9 CaCl2(2H2O), 2.5 MgCl2(6H2O), 5 Na2ATP, 10 EGTA, and 40 HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4. For ion substitution experiments, currents for determining the reversal potential were first recorded for an individual cell for one condition (control or ion substituted). The bathing solution was then switched for the alternate solution, and a new current-voltage (I-V) relationship was determined in that cell. For K+-replacement experiments, after currents in one solution were recorded, the cell was patched again with a new pipette containing the alternate intracellular solution, and 10 min were allowed for the new solution to dialyze the cell interior before current measurements were made. For other ions, the intracellular solution remained the same throughout the experiment.

In Na+-replacement experiments, ASW was replaced with a solution containing (in mM) 417 N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG), 10 KCl, 10 CaCl2(2H2O), 55 MgCl2(6H2O), and 15 HEPES-HCl, pH 7.6, whereas ICS was replaced with solution containing (in mM) 458 KCl, 2.9 CaCl2(2H2O), 2.5 MgCl2(6H2O), 5 K2ATP, 10 EGTA, and 40 HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4.

In K+-replacement experiments, ASW was replaced with solution containing (in mM) 417 NaCl, 10 NMDG, 10 CaCl2(2H2O), 55 MgCl2(6H2O), and 15 HEPES-HCl, pH 7.6, whereas ICS was replaced with a solution containing (in mM) 458 NMDG, 2.9 CaCl2(2H2O), 2.5 MgCl2(6H2O), 5 Na2ATP, 10 EGTA, and 40 HEPES-HCl, pH 7.4.

For Ca2+-removal experiments, ASW was replaced with a solution containing (in mM) 417 NaCl, 10 KCl, 55 MgCl2(6H2O), 10 NMDG, 1 EGTA, and 15 HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.6. For Ca2+-addition experiments, ASW was replaced with a solution containing (in mM) 417 NaCl, 10 KCl, 65 CaCl2(2H2O), and 15 HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.6.

For Mg2+-replacement experiments, ASW was replaced with a solution containing (in mM) 417 NaCl, 10 KCl, 10 CaCl2(2H2O), 83 NMDG, and 15 HEPES-HCl, pH 7.6, whereas ICS was the same as control.

For Cl−-replacement experiments, ASW was replaced with a solution containing (in mM) 417 Na-gluconate, 10 K-gluconate, 10 CaCl2(2H2O), 55 MgCl2(6H2O), and 15 HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.6, whereas ICS was the same as control. Data were corrected for a −17-mV junction potential arising in this solution.

Data analysis.

Significance of within-group comparisons was assessed using Student's paired t-test, and the unpaired (2 sample) t-test was used for between-group comparisons. Analyses were performed using Data Desk software (version 6.2; Data Description, Ithaca, NY). Differences at P < 0.05 were accepted as significant. Data are means ± SD.

RESULTS

Electrophysiological responses of Aplysia neurons to d-Asp.

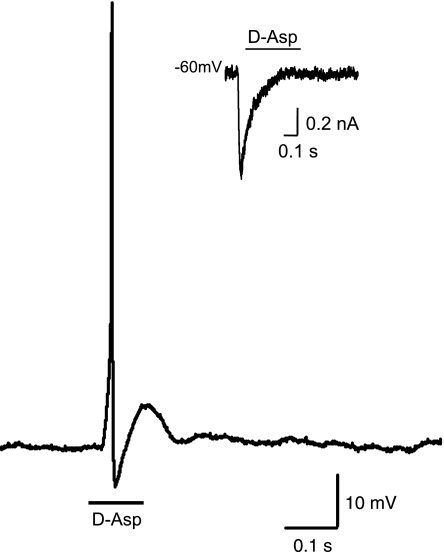

d-Asp-induced currents were present in 54.1% of cultured BSC neurons examined (n = 37), 28.6% of non-BSC buccal neurons (n = 7), 18.8% of abdominal ganglion bag cell neurons (n = 16), 40.0% of unidentified cerebral ganglion neurons (n = 25), 45.8% of pleural ventral caudal neurons (n = 59), and 31.3% of unidentified neurons of the pleural ganglion (n = 16). In some neurons, pressure application of d-Asp elicited an action potential under current-clamp conditions (Fig. 1) that corresponded to an inward current near the resting potential under voltage clamp (Fig. 1, inset), whereas d-Asp elicited only subthreshold depolarizations in others (data not shown). Pressure application of ASW was without effect on BSC neurons (data not shown), indicating excitatory responses were due to the presence of d-Asp.

Fig. 1.

Action potential in a buccal S cluster (BSC) neuron evoked by pressure application of d-Asp (1 mM; 100 ms). Membrane potential (Vm) = −35 mV. Inset: d-Asp-activated whole cell current in the same BSC cell at Vm = −60 mV.

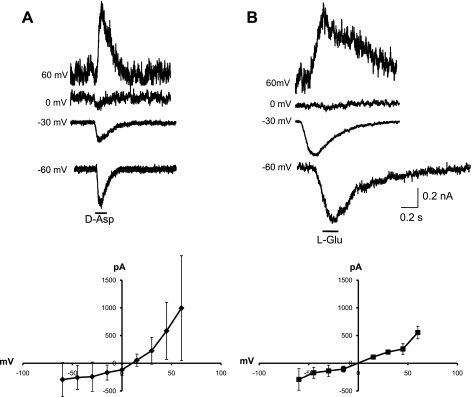

Under voltage-clamp conditions, some BSC neurons responded to both d-Asp and l-Glu in alternate applications of these agonists. Whole cell currents induced by d-Asp and l-Glu were inward at negative voltages, e.g., −60 and −30 mV, and outward at depolarized voltages, e.g., 60 mV (Fig. 2, A and B). d-Asp- and l-Glu-activated currents possessed a similar I-V relationship. l-Glu-activated currents reversed at −0.4 ± 9.3 mV (n = 7), whereas d-Asp-activated currents reversed at 7.7 ± 9.0 mV (n = 37) in ASW medium and KCl intracellular solution. There was no significant difference in reversal potential between d-Asp- and l-Glu-activated currents; however, currents induced by d-Asp displayed a slight outward rectification compared with those induced by l-Glu (Fig. 2, A and B). In 71 cells in which both agonists were tested, 18 (25.4%) responded to both l-Glu and d-Asp, whereas 35 (49.3%) responded only to l-Glu and 18 (25.4%) responded only to d-Asp, which was significantly different from our expectation (χ2 goodness of fit, P < 0.05). Currents activated by l-Glu also displayed a slower time course of activation and inactivation compared with those activated by d-Asp (Fig. 3, A and B; Table 1). Once pressure-applied agonist reached the cell membrane, evidenced by an inflection of the current baseline, d-Asp currents reached peak activation significantly faster than l-Glu currents (P < 0.05, 2-sample t-test). To determine whether duration of agonist exposure affected maximum current or current decay, we compared spontaneous and steady-state current decay. Both spontaneous inactivation in response to a brief, 5-ms pulse of agonist and steady-state inactivation in response to 3-s pulses of agonist were also significantly faster for d-Asp than for l-Glu (P < 0.05, 2-sample t-test), but spontaneous and steady-state inactivation times for d-Asp were not different, suggesting d-Asp currents rapidly desensitize.

Fig. 2.

BSC whole cell currents in response to pressure application of d-Asp and l-Glu. A: d-Asp-evoked currents in a single BSC cell at different holding potentials (1 mM; 100 ms as indicated by horizontal bar). Graph indicates average (±SD) current-voltage (I-V) relationship (n = 55). B: l-Glu-evoked currents in a BSC cell at different holding potentials (1 mM; 100 ms as indicated by horizontal bar). Graph indicates average (±SD) I-V relationship (n = 8).

Fig. 3.

Activation and inactivation of d-Asp and l-Glu whole cell currents and desensitization of d-Asp currents. A: example d-Asp (left) and l-Glu (right) currents in response to brief (5 ms) and sustained (3 s) agonist application. B: example time courses of activation and inactivation for d-Asp- and l-Glu-induced currents (1 mM, 100 ms). The data were fit using a double-exponential Simplex/SSE algorithm (Axograph). Insets: fast (τF; solid lines) and slow (τS; dashed lines) activation time constants of d-Asp- and l-Glu-induced currents. d-Asp: activation, τF = 4.2 ms and τS = 12.4 ms; inactivation, τF = 8.8 ms and τS = 151.2 ms. l-Glu: activation, τF = 6.63 ms and τS = 40.5 ms; inactivation, τF = 15.0 ms and τS = 175 ms. C: superimposed currents in the same BSC cell elicited in response to 2 applications of d-Asp (left) and l-Glu (right). Applications 1 and 2 are separated by 10 s.

Table 1.

Activation and inactivation times and time constants for pressure-applied d-Asp and l-Glu

| Activation (100 ms agonist) |

Inactivation (100 ms agonist) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time, ms | τF | τS | Spontaneous Inactivation (5 ms agonist) |

Steady-State Inactivation (3 s agonist) |

τf | τs | |

| d-Asp | 67.9 ± 28.8* (22) | 2.9 ± 0.9* (5) | 12.7 ± 9.9* (5) | 401 ± 223* (16) | 497 ± 314* (12) | 7.5 ± 4.2* (5) | 80.4 ± 46.6* (5) |

| l-Glu | 121 ± 74.7 (21) | 6.2 ± 2.5 (5) | 38.1 ± 12.3 (5) | 657 ± 462 (15) | 595 ± 399 (6) | 21.8 ± 11.6 (5) | 171 ± 49.4 (5) |

Values are means ± SD (no. of neurons is given in parentheses).

P < 0.05, d-Asp vs. l-Glu for the indicated measure.

Time constants for activation and inactivation reflected the differences in the kinetics of d-Asp- and l-Glu-evoked currents. The fast and slow activation time constants, τF and τS, of d-Asp currents were significantly shorter than those for l-Glu (P < 0.05 for τF and P < 0.01 for τS, 2-sample t-test).

An important distinction between currents elicited by d-Asp and those elicited by l-Glu, in addition to the greater vulnerability of d-Asp currents to desensitization, was their recovery from desensitization. Whereas d-Asp-activated currents rapidly desensitized during repeated applications of agonist, l-Glu-activated currents recovered from apparent desensitization promptly and potentiated over the same time course that produced desensitization in d-Asp currents (Fig. 3C). d-Asp currents recovered from desensitization and returned to maximal amplitude at interpulse intervals of ∼40 s (Fig. 4A). Half-time potential (T1/2) for recovery was 13 s, whereas τ was 18.79 s. In contrast, T1/2 for recovery of full-amplitude l-Glu currents was <500 ms (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Dependence of whole cell d-Asp current amplitude on frequency of agonist application and on concentration. A: normalized average (±SD) current amplitude in response to a second application of d-Asp in a 2-pulse protocol as a function of the increasing interval between application over 2- to 44-s intervals. Line is fitted to a single-exponential equation (Robert and Howe 2003): It = [Imax − (Imax − I0)exp(−t/τ)] (n = 8; half-time for recovery = 13 s; τ = 18.79). B: average (±SD) dose response for d-Asp. Line is fitted to a Boltzmann equation (Verdoorn and Dingledine 1988): I = Imax/[1 + (EC50/[agonist])nH] (n = 6). See text for definitions.

Dose-response data were obtained using concentrations of d-Asp between 3 μM and 10 mM (Fig. 4B). Currents were half-maximal at a concentration of ∼42 μM d-Asp. The Hill slope coefficient for the fitted curve was 0.67. Current amplitude was maximal at ≥1 mM d-Asp.

Ion permeability of d-Asp-activated channels.

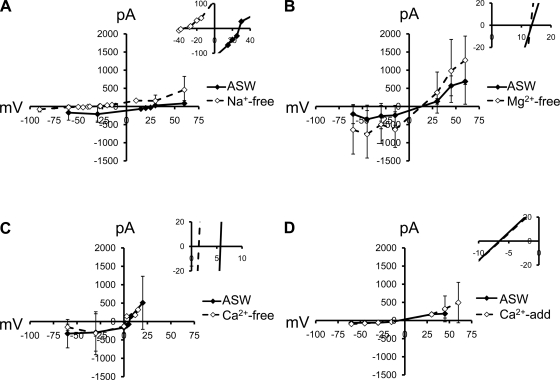

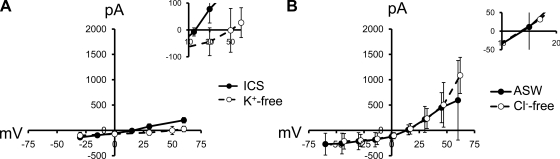

Each of the major ions in solution was systematically replaced with a larger, theoretically impermeant ion to determine which ions contributed to whole cell d-Asp-induced currents. Significant shifts in the reversal potential under these conditions indicate channel permeation for that ion. Figures 5 and 6 summarize these results.

Fig. 5.

Average I-V relationships in d-Asp currents with external cation replacement and higher resolution view of reversal potentials (insets). A: significant reversal potential shift of −47 mV after replacement of external Na+ with N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) (P < 0.05; n = 7). B: absence of shift in reversal potential shift after replacement of external Mg2+ with NMDG (n = 10). C: absence of shift in reversal potential after replacement of external Ca2+ with NMDG (n = 12). D: absence of shift in reversal potential after replacement of external Ca2+ and Mg2+ (n = 6). ASW, artificial seawater.

Fig. 6.

I-V relationships of d-Asp currents with K+ and Cl− replacement and higher resolution view of reversal potentials (insets). A: significant reversal potential shift of 34 mV after replacement of internal K+ with NMDG (P < 0.05; n = 7). B: I-V relationships before and after replacement of external NaCl with Na-gluconate (n = 9).

Na+ in the ECS was replaced with NMDG, which resulted in a significant negative shift in reversal potential of 47 mV (P < 0.01, Student's paired t-test; n = 7), indicating that Na+ was permeant (Fig. 5A). K+ in the intracellular solution was also replaced with NMDG and caused a positive shift in reversal potential of 34 mV (Fig. 6A; P < 0.01, Student's paired t-test; n = 7), indicating that K+ was permeant.

External Ca2+ was replaced in the ECS with NMDG, in addition to the addition of 1 mM EGTA to the ECS to chelate any residual Ca2+ (Fig. 5C). Replacing Ca2+ did not result in a shift in reversal potential from currents in Ca2+-containing ASW (n = 12). Because this apparent absence of a reversal potential shift may have been due to the small amount of Ca2+ being excluded (ASW contains 10 mM), Ca2+ permeability was further investigated by replacing external Mg2+ with additional Ca2+. Addition of 55 mM extra Ca2+ did not cause a shift in reversal potential (Fig. 5D; n = 6). The absence of a shift when Ca2+ was either excluded or amended in the ECS indicated d-Asp channels were not permeable to Ca2+. Thus d-Asp activated a nonspecific cation channel that excluded Ca2+.

Mg2+ was also replaced with NMDG to test for voltage-dependent block or permeation through d-Asp channels (Fig. 5B). Replacing external Mg2+ with NMDG did not cause a significant shift in reversal potential (n = 10). Removing Mg2+ caused an increase in current amplitude at voltages ranging from −60 to −15 mV (at −60 mV, amplitude was increased 306 ± 228%; at −45 mV, 217 ± 193%; at −30 mV, 189 ± 159%; and at −15 mV, 263 ± 180%; P < 0.05, Student's paired t-test; n = 10). Current amplitudes at positive voltages in Mg2+-free conditions were not significantly different from those in ASW that contained 55 mM Mg2+. Thus d-Asp-activated currents appeared to possess voltage-dependent block by Mg2+ similar to that of NMDA receptor channels but lacked the Ca2+ permeability of NMDA channels.

External Cl− was replaced to determine whether this anion contributed to whole cell d-Asp-induced currents (Fig. 6B). NaCl, the major ionic constituent of the ECS, was replaced with Na-gluconate. After correction for a 17-mV junction potential generated by the switch to gluconate, the reversal potential was not significantly different from that in ASW, suggesting that Cl− does not permeate d-Asp-activated channels.

DISCUSSION

The excitatory Na+ and K+ current activated by d-Asp in BSC neurons had a Hill coefficient for agonist binding near 1, indicating independent binding of d-Asp to its target receptors. These results are consistent with those observed for d-Asp at NMDAR and non-NMDARs expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Verdoorn and Dingledine 1988) and for l-Glu channels at higher agonist concentrations (Patneau and Mayer 1990). Similarities between the whole cell currents induced by d-Asp and l-Glu in BSC cells were their activation ranges, current amplitudes, relatively slow activation and inactivation, and desensitization. These features are most similar to the kinetics of NMDAR channels (Dingledine et al. 1999; Paoletti 2011), the purported site of action of d-Asp (Huang et al. 2005; Kiskin et al. 1990; Olverman et al. 1988). Yet in contrast to l-Glu currents in Aplysia, d-Asp currents had faster kinetics, an outward rectification of the I-V relationship, and a prolonged desensitization on repeated applications of agonist, requiring ∼40 s for current amplitude to fully recover. l-Glu currents recovered from desensitization quickly and potentiated as currents were elicited multiple times, characteristic of known l-Glu channels (Heckmann and Dudel 1997; Vicini et al. 1998; Wilding and Huettner 1997).

One of the most conspicuous characteristics distinguishing NMDAR channels from non-NMDAR channels is a high Ca2+ permeability (Mayer and Westbrook 1987), not observed presently with d-Asp, and voltage-sensitive Mg2+ block (Ascher and Nowak 1988; Dale and Kandel 1993), which we did observe. Since Aplysia has both NMDA-like receptors and AMPA-like receptors free of constitutive block by Mg2+ (Li et al. 2005), d-Asp may act at these receptors and/or at novel receptors.

The assertion that d-Asp activates non-l-Glu channels is supported by the observation that approximately one-quarter of BSC cells responded to both l-Glu and d-Asp, whereas another one-quarter responded only to d-Asp and not to l-Glu. Although previous reports have demonstrated separate actions of the l-isoform of aspartate and l-Glu in Aplysia (Yarowsky and Carpenter 1976), d- and l-Asp appear to act independently in BSC neurons (Carlson and Fieber, in press). These data reflect previous results from our laboratory in pleural ganglia (Fieber et al. 2010) but contrast with earlier findings that d-Asp is an alternate agonist of l-Glu channels in vertebrate brain (Kiskin et al. 1990; Olverman et al. 1988). Our results are consistent with findings of Errico et al. (in press) in mouse hippocampal neurons, in which d-Asp activated NMDA receptors but generated excitatory postsynaptic potentials persisting under conditions of NMDAR block. Correspondingly, we demonstrated that d-Asp elicits currents in Aplysia BSC cells that lacked AMPAR and NMDAR currents (Carlson and Fieber, in press). It is possible that the current responses observed in this study represent a mixed population of receptor channels, with d-Asp activating a combination of NMDAR channels and another non-l-Glu channel. This could confound interpretation of results involving d-Asp-induced currents, since some of the channel ion-conducting characteristics observed in this study could be attributed to l-Glu receptor channels. The reported observations, however, were consistent with activation of a population of receptor channels distinct from, at least, l-Glu-activated NMDARs. The finding that d-Asp current responses are modulated by similar mechanisms to AMPAR responses (Carlson and Fieber, in press) suggests that d-Asp activation of a putative d-Asp receptor may substitute for l-Glu activation of AMPARs in some Aplysia neurons. Pharmacological antagonists targeting different l-Glu receptor subtypes may be useful in elucidating the identity of channels activated by both l-Glu and d-Asp and is an area of emphasis. Additional characterization of the endogenous neurotransmitter role of d-Asp will benefit from the use of synaptic preparations, as well as molecular characterization of the receptors activated by d-Asp.

The modulatory actions of d-Asp in previous studies (Brown et al. 2007; Dale and Kandel 1993; Gong et al. 2005) might be explained in terms of high-affinity binding of d-Asp to its receptor, slowing recovery from desensitization (Zhang et al. 2006). d-Asp binding may provide an endogenous mechanism of synaptic modulation if d-Asp binds with high affinity to l-Glu receptors but does not activate them.

Furthermore, the long desensitization time of d-Asp currents may be important in the physiology of the channel, representing an endogenous mechanism for protection from excitotoxicity (Trussel and Fischbach 1989). Cross-activation of d-Asp with l-Glu receptors in mammalian systems may be protective in this respect, and lower levels of free d-Asp in patients with Alzheimer's disease would support this hypothesis (D'Aniello et al. 1998).

Our results demonstrate features of the channels activated by d-Asp in the nervous system of Aplysia. d-Asp may have multiple sites of action, similar to l-Glu, and may overlap with l-Glu receptors. Several of our recent results, including some described in this report, however, allude to an undescribed receptor.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant P40RR01029, the Korein Foundation, and a University of Miami Fellowship to S. L. Carlson.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge assistance from the staff of the University of Miami Aplysia Resource.

Present address of S. L. Carlson: Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Campus Box 7178, Thurston Bowles Building, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7178.

REFERENCES

- Antzoulatos EG, Byrne JH. Learning insights transmitted by glutamate. Trends Neurosci 27: 555–560, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascher P, Nowak L. The role of divalent cations in the N-methyl-d-aspartate responses of mouse central neurons in culture. J Physiol 399: 247–266, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ER, Piscopo S, Chun JT, Francone M, Mirabile I, D'Aniello A. Modulation of an AMPA-like glutamate receptor (SqGluR) gating by l- and d-aspartic acids. Amino Acids 32: 53–57, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SL, Fieber LA. Unique ionotropic receptors for d-aspartate are a target for serotonin-induced synaptic plasticity in Aplysia californica. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis DR, Watkins JC. Amino acids with strong excitatory actions on mammalian neurons. J Physiol 166: 1–14, 1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N, Kandel ER. l-Glutamate may be the fast excitatory transmitter of Aplysia sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 7163–7167, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aniello A. d-aspartic acid: an endogenous amino acid with an important neuroendocrine role. Brain Res 53: 215–234, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aniello A, Lee JM, Petrucelli L, Di Fiore MM. Regional decrease of free d-Aspartate levels in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett 250: 131–134, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aniello A, Nardi G, Vetere A, Ferguson GP. Occurrence of free d-aspartic acid in the circumoesophaeal ganglia of Aplysia fasciata. Life Sci 52: 733–736 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies LP, Johnston GA. Uptake and release of d- and l-aspartate by rat brain slices. J Neurochem 26: 1007–1014, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev 51: 7–61, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errico F, Nisticò R, Napolitano F, Mazzola C, Astone D, Pisapia T, Giustizieri M, D'Aniello A, Mercuir NB, Ussielo A. Increased d-aspartate brain content rescues hippocampal age-related synaptic plasticity deterioration of mice. Neurobiol Aging. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errico F, Nistico R, Palma G, Federici M, Affuso A, Brilli E, Topo E, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Bozzi Y, D'Aniello A, Di Lauro R, Mercuri NB, Usiello A. Increased levels of d-aspartate in the hippocampus enhance LTP but do not facilitate cognitive flexibility. Mol Cell Neurosci 37: 236–246, 2008a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errico F, Rossi S, Napolitano F, Catuogno V, Topo E, Fisone G, D'Aniello A, Centonze D, Usiello A. d-Aspartate prevents corticostriatal long-term depression and attenuates schizophrenia-like symptoms induced by amphetamine and MK-801. J Neurosci 28: 10404–10414, 2008b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieber LA. The development of excitatory capability in Aplysia californica bag cells observed in cohorts. Dev Brain Res 122: 47–58, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieber LA, Carlson SL, Capo TR, Schmale MC. Changes in d-aspartate ion currents in the Aplysia nervous system with aging. Brain Res 1343: 28–36, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs SA, Berger R, Klomp LWJ, De Koning TJ. d-Amino acids in the central nervous system in health and disease. Mol Genet Metab 85: 168–180, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuchi F, Homma H. Free d-aspartate in mammals. Biol Pharm Bull 28: 1566–1570, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong XQ, Frandsen A, Lu WY, Wan Y, Zabek RL, Pickering DS, Bai D. d-Aspartate and NMDA, but not l-aspartate, block AMPA receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. Br J Pharmacol 145: 449–459, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha TJ, Kohn AB, Bobkova YV, Moroz LL. Molecular characterization of NMDA-like receptors in Aplysia and Lymnaea: relevance to memory mechanisms. Biol Bull 210: 255–270, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann M, Dudel J. Desensitization and resensitization kinetics of glutamate receptor channels from Drosophila larval muscle. Biophys J 72: 2160–2169, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma H. Biochemistry of d-aspartate in mammalian cells. Amino Acids 32: 3–11, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Sinha SR, Fedoryak OD, Ellis-Davies GCR, Bergles DE. Synthesis and characterization of 4-methoxy-7-nitroindolinyl-d-aspartate, a caged compound for selective activation of glutamate transporters and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in brain tissue. Biochemistry 44: 3316–3326, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahan-Parwar B, Fredman SM. Cerebral ganglion of Aplysia: cellular organization and origin of nerves. Comp Biochem Physiol 54A: 347–357, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PM, Duan X, Huang AS, Liu CY, Ming GL, Snyder SH. Aspartate racemase, generating neuronal d-aspartate, regulates adult neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3175–3179, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WM, Carpenter DO. Voltage-clamp characterization of Cl− conductance gated by GABA and l-glutamate in single neurons of Aplysia. J Neurophysiol 61: 892–899, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiskin NI, Krishtal OA, Tsyndrenko AY. Cross-desensitization reveals pharmacological specificity of excitatory amino acid receptors in isolated hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci 2: 461–470, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Roberts AC, Glanzman DL. Synaptic facilitation and behavioral dishabituation in Aplysia: dependence on release of Ca from postsynaptic intracellular stores, postsynaptic exocytosis, and modulation of postsynaptic AMPA receptor efficacy. J Neurosci 25: 5623–5637, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YM, Schneider M, Sticha CM, Toyooka T, Sweedler JV. Separation of amino acid and peptide stereoisomers by nonionic micelle-mediated capillary electrophoresis after chiral derivatization. J Chromatogr A 800: 345–354, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL. Permeation and block of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor channels by divalent cations in mouse cultured central neurons. J Physiol 394: 501–527, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Subcellular analysis of d-Aspartate. Anal Chem 77: 7190–7194, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H, Rubakhin SS, Scanlan CR, Wang L, Sweedler JV. d-Aspartate as a putative cell-cell signaling molecule in the Aplysia californica central nervous system. J Neurochem 97: 595–606, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olverman HJ, Jones AW, Mewett KN, Watkins JC. Structure/activity relations of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor ligands as studied by their inhibition of [3H]d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid binding in rat brain membranes. Neuroscience 26: 17–31, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P. Molecular basis of NMDA receptor functional diversity. Eur J Neurosci 33: 1351–1365, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patneau DK, Mayer ML. Structure-activity relationships for amino acid transmitter candidates acting at N-methyl-d-aspartate and quisqualate receptors. J Neurosci 10: 2385–2399, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert A, Howe JR. How AMPA receptor desensitization depends on receptor occupancy. J Neurosci 23: 847–858, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DD, Galindo R, Queen SA, Paxton LL, Allan AM. Characterization of electrically evoked [3H]-d-aspartate release from hippocampal slices. Neurochem Int 38: 255–267, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan C, Shi T, Hatcher NG, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Synthesis, accumulation, and release of d-aspartate in the Aplysia californica CNS. J Neurochem 115: 1234–1244, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli P, Brown E, Ferrandino G, Branno M, Montarolo PG, D'Aniello E, Rastogi RK, D'Aniello B, Chieffi G, Fisher GH, D'Aniello A. d-Aspartic acid in the nervous system of Aplysia limacina: possible role in neurotransmission. J Cell Physiol 206: 672–681, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussel LO, Fischbach GD. Glutamate receptor desensitization and its role in synaptic transmission. Neuron 3: 209–218, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoorn TA, Dingledine R. Excitatory amino acid receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes: agonist pharmacology. Mol Pharmacol 34: 298–307, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicini S, Wang JF, Li JH, Zhu WJ, Wang YH, Luo JH, Wolfe BB, Grayson DR. Functional and pharmacological differences between recombinant N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. J Neurophysiol 79: 555–566, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waagepetersen HS, Shimamoto K, Schousboe A. Comparison of effects of DL-threo-beta-benzyloxyaspartate (DL-TBOA) and l-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylate (t-2,4-PDC) on uptake and release of [3H]d-aspartate in astrocytes and glutamatergic neurons. Neurochem Res 26: 661–666, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ota N, Romanova EV, Sweedler JV. A novel pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent amino acid racemase in the Aplysia californica central nervous system. J Biol Chem 286: 13765–13774, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilding TJ, Huettner JE. Activation and desensitization of hippocampal kainate receptors. J Neurosci 17: 2713–2721, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolosker H, D'Aniello A, Snyder SH. d-Aspartate disposition in neuronal and endocrine tissues: ontogeny, biosynthesis and release. Neuroscience 100: 183–189, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada R, Kera Y, Takahashi S. Occurrence and functions of free d-aspartate and its metabolizing enzymes. Chem Rec 6: 259–266, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarowsky PJ, Carpenter DO. Aspartate: distinct receptors on Aplysia neurons. Science 192: 807–809, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Robert A, Vogensen SB, Howe JR. The relationship between agonist potency and AMPA receptor kinetics. Biophys J 91: 1336–1346, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]