Abstract

In songbirds, the basal ganglia outflow nucleus LMAN is a cortical analog that is required for several forms of song plasticity and learning. Moreover, in adults, inactivating LMAN can reverse the initial expression of learning driven via aversive reinforcement. In the present study, we investigated how LMAN contributes to both reinforcement-driven learning and a self-driven recovery process in adult Bengalese finches. We first drove changes in the fundamental frequency of targeted song syllables and compared the effects of inactivating LMAN with the effects of interfering with N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent transmission from LMAN to one of its principal targets, the song premotor nucleus RA. Inactivating LMAN and blocking NMDA receptors in RA caused indistinguishable reversions in the expression of learning, indicating that LMAN contributes to learning through NMDA receptor-mediated glutamatergic transmission to RA. We next assessed how LMAN's role evolves over time by maintaining learned changes to song while periodically inactivating LMAN. The expression of learning consolidated to become LMAN independent over multiple days, indicating that this form of consolidation is not completed over one night, as previously suggested, and instead may occur gradually during singing. Subsequent cessation of reinforcement was followed by a gradual self-driven recovery of original song structure, indicating that consolidation does not correspond with the lasting retention of changes to song. Finally, for self-driven recovery, as for reinforcement-driven learning, LMAN was required for the expression of initial, but not later, changes to song. Our results indicate that NMDA receptor-dependent transmission from LMAN to RA plays an essential role in the initial expression of two distinct forms of vocal learning and that this role gradually wanes over a multiday process of consolidation. The results support an emerging view that cortical-basal ganglia circuits can direct the initial expression of learning via top-down influences on primary motor circuitry.

Keywords: birdsong, motor learning, basal ganglia, N-methyl-d-aspartate, lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium

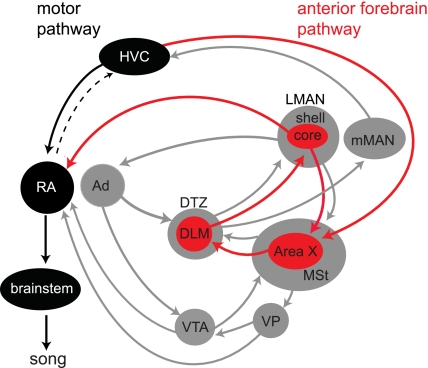

birdsong is an ideal behavior for probing how basal ganglia circuits contribute to learning, because the dedicated neural pathways that control song production and song learning are well-elucidated and highly amenable to experimental monitoring and manipulation. These neural pathways include a song motor pathway that controls much of the moment-by-moment structure of song, as well as a cortical-basal ganglia circuit, the anterior forebrain pathway (AFP), that plays a crucial role in juvenile song learning and adult vocal plasticity (Fig. 1) (Andalman and Fee 2009; Bottjer et al. 1984; Brainard and Doupe 2000; Nordeen and Nordeen 2010; Scharff and Nottebohm 1991; Williams and Mehta 1999).

Fig. 1.

Neural circuitry contributing to song production and learning. Neural pathways that control song production and learning include a song motor pathway (black nuclei and arrows) that controls much of the moment-by-moment structure of song, as well as a cortical-basal ganglia circuit, the anterior forebrain pathway (AFP; red nuclei and arrows), that plays a crucial role in juvenile song learning and adult vocal plasticity. The song motor pathway includes forebrain nuclei HVC and RA, analogous to vocal motor cortex. RA projects to brain stem structures that control the vocal musculature; changes in RA activity are likely to underlie learned changes to syllable structure (Leonardo and Fee 2005; Sober et al. 2008; Vu et al. 1994; Yu and Margoliash 1996). The lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN), a cortical analog that is part of the AFP, plays a crucial role in juvenile and adult song plasticity. LMAN activity could influence RA during learning via a number of direct and indirect pathways. Neurons in LMAN core make direct glutamatergic projections onto RA neurons and also are thought to release neurotrophins onto RA neurons. Neurons in LMAN core also project to the basal ganglia homolog Area X, which is well positioned to influence activity in neuromodulatory nuclei such as ventral pallidum (VP), a cholinergic nucleus projecting to RA and HVC, as well as the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a dopaminergic nucleus that also projects to RA and HVC (Appeltants et al. 2000, 2002; Gale and Perkel 2010; Gale et al. 2008; Li and Sakaguchi 1997). LMAN activity could also influence RA activity via indirect projections from LMAN shell to the motor pathway. The LMAN shell, part of a distinct motor circuit that plays a functional role in song learning, projects to both the Ad and the medial striatum (MSt), surrounding Area X (Bottjer and Altenau 2010; Iyengar et al. 1999). DLM, medial dorsolateral nucleus of thalamus; DTZ, dorsal thalamic zone; mMAN, medial magnocellular nucleus of anterior nidopallium. [Adapted from Bottjer and Altenau (2010) and Gale et al. (2008).]

The influence of the AFP on song production and learning has been demonstrated by silencing the lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN). LMAN is a cortical analog that receives input from the basal ganglia via the thalamus and projects to multiple targets, including the song premotor nucleus RA, an analog of primary vocal motor cortex (Fig. 1). Lesions or inactivations of LMAN in juvenile birds cause an abrupt and premature stabilization of an abnormally simple song and prevent the subsequent progression of song learning (Bottjer et al. 1984; Olveczky et al. 2005; Scharff and Nottebohm 1991). In contrast, lesions or inactivations of LMAN in adults reduce rendition-to-rendition variation in the acoustic structure of song syllables but do not affect the gross structure of stable adult song (Hampton et al. 2009; Kao and Brainard 2006; Kao et al. 2005; Nordeen and Nordeen 1993; Stepanek and Doupe 2010).

Lesions of LMAN, however, do prevent several forms of adult song plasticity that can normally be elicited by altered sensory experience (Brainard and Doupe 2000; Morrison and Nottebohm 1993; Thompson and Johnson 2007; Williams and Mehta 1999). Moreover, lesions or inactivations of LMAN can also reverse the expression of recently induced adult song plasticity and learning. For instance, lesions of LMAN partially reverse both the song deterioration that results from deafening and the song deterioration that results from microlesions made within the song motor pathway (Nordeen and Nordeen 2010; Thompson et al. 2007). Similarly, Andalman and Fee (2009) found that pharmacological inactivation of LMAN in adult birds partially reverses changes to syllable structure induced in an aversive reinforcement learning paradigm. The extent to which silencing LMAN reverses the expression of plasticity seems to diminish over time, indicating that a consolidation process occurs in which the expression of learning becomes LMAN independent (Andalman and Fee 2009; Nordeen and Nordeen 2010).

In the present study we addressed several questions about how LMAN contributes to the expression of adult learning: 1) Via which circuitry does LMAN contribute to the expression of learning? 2) Over what time course does learning become consolidated so that its expression no longer depends on LMAN? 3) Does this consolidation correspond with the establishment of lasting changes to song structure? 4) Do LMAN's contributions generalize across distinct forms of adaptive adult learning?

First, we investigated the neural circuitry through which LMAN influences the expression of learning (Andalman and Fee 2009). Ultimately, the expression of learning is likely mediated by changes in the pattern of activity in the song premotor nucleus RA during singing; RA projects to the brain stem circuitry controlling vocal musculature, and RA activity has been strongly linked to the moment-by-moment control of song structure (Leonardo and Fee 2005; Sober et al. 2008; Vu et al. 1994; Yu and Margoliash 1996). There are several direct and indirect pathways by which LMAN could affect RA activity (Fig. 1). One attractive hypothesis is that LMAN exerts its primary influence on the initial expression of adult song learning via direct projections from its central region, LMAN core, to RA. Projections from LMAN core to RA could influence RA activity through the release of glutamate or the release of neurotrophins (Akutagawa and Konishi 1998; Johnson et al. 1997; Kittelberger and Mooney 2005; Mooney 1992; Mooney and Konishi 1991; Stark and Perkel 1999). However, neurons in LMAN core also project to Area X, a basal ganglia homolog that is well-positioned to influence RA activity via projections from Area X to neuromodulatory nuclei thought to participate in acute control of song production and learning (Fig. 1; Appeltants et al. 2002; Gale and Perkel 2010; Li and Sakaguchi 1997). In addition, neurons in LMAN shell, surrounding the LMAN core, project to Ad, which is part of a distinct circuit involved in juvenile song learning (Bottjer and Altenau 2010; Iyengar et al. 1999). Pharmacological inactivations targeting LMAN presumably affect neural activity in both LMAN core and LMAN shell. Moreover, such inactivations could exert their influence by either preventing excitatory glutamatergic transmission or preventing neurotrophin release at diverse downstream targets. Hence, silencing LMAN activity could affect the expression of learning via multiple pathways and mechanisms.

We directly tested the possibility that glutamatergic transmission from LMAN to RA mediates LMAN's role in the expression of learning. To do so, we compared the effects of inactivating LMAN with the effects of blocking N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in RA. Glutamatergic transmission from LMAN core to RA relies primarily on activation of NMDA receptors in RA, whereas glutamatergic transmission within the direct motor pathway is mediated by a mixture of NMDA and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) receptors (Mooney 1992; Mooney and Konishi 1991; Stark and Perkel 1999). Therefore, blocking NMDA receptors in RA should preferentially block glutamatergic transmission from LMAN to RA while having a lesser effect on transmission within the motor pathway itself. Indeed, a previous study showed that infusing AP5, an NMDA receptor antagonist, into RA of juvenile birds caused similar effects on the variability of song as inactivating LMAN (Olveczky et al. 2005), suggesting that blocking NMDA receptors in RA functionally deafferents RA from its glutamatergic LMAN inputs. In the present study, we therefore infused AP5 into RA to determine whether LMAN-RA glutamatergic transmission mediates LMAN's contributions to the expression of song learning. We found that infusion of AP5 into RA and inactivation of LMAN similarly reverses the initial expression of learned changes to syllable structure, suggesting that LMAN's contributions to the expression of learning are mediated by direct glutamatergic projections from LMAN core to RA, rather than through LMAN's projections to other targets.

Second, we addressed how the contributions of LMAN to the expression of learning change over time. Andalman and Fee (2009) inactivated LMAN while driving continuous changes to the fundamental frequency (FF) of targeted syllables via aversive reinforcement. The amount of reversion caused by inactivating LMAN on a given day tended to correspond with the amount of learning that had already occurred on that day. This correspondence indirectly suggests that learning from prior days may become completely consolidated overnight in the sense that the expression of prior learning no longer requires LMAN activity. However, this possibility was not tested directly because learned changes to FF were not held at a constant value from one day to the next. In the present study, we tested the time course of consolidation directly by maintaining FF at a fixed, learned offset from baseline for several days while inactivating LMAN periodically. We found, as reported by Andalman and Fee (2009), that LMAN inactivation initially causes a large reversion of learned changes in FF back toward the initial (prelearning) baseline value. However, we found that the effects of LMAN inactivation on the expression of learning only gradually decline, over a period of multiple days. These results are incompatible with a model in which learned changes to song become completely consolidated in a single night and instead suggest a multiday process of consolidation.

Third, we tested whether this slow consolidation process results in the stable retention of learned changes to song. Indeed, in other forms of motor learning, analogous processes of consolidation result in the lasting retention of learned changes to behavior (e.g., Brashers-Krug et al. 1996; Joiner and Smith 2008; Shadmehr and Holcomb 1997). In the present study, however, we found that this is not the case; even after learning becomes consolidated (in the sense that LMAN is no longer required for the expression of learned changes to FF), cessation of external reinforcement results in a gradual recovery of song to its original structure. This indicates that the brain retains a lasting representation of the original song structure and both the capacity and impetus to restore song to that structure even following a consolidation process in which control over the expression of learning has been transferred to song motor circuitry that can operate independently of LMAN.

Finally, we took advantage of this self-driven recovery, which occurs spontaneously in the absence of external instruction, to test whether LMAN's contributions to the expression of learning generalize across different forms of learning. The mechanisms by which LMAN contributes to learning driven by aversive reinforcement (Andalman and Fee 2009; Charlesworth et al. 2011; Tumer and Brainard 2007) may be distinct from the mechanisms by which LMAN contributes to juvenile song learning or to other forms of song learning that rely on error correction rather than external reinforcement (Mooney 2009a; Sober and Brainard 2009). We found that inactivating LMAN and blocking NMDA receptors in RA during the process of self-driven recovery causes a reemergence of previously learned changes to song (and a shift in song structure away from the original baseline). This indicates that for self-driven song recovery, as for externally instructed learning, the initial expression of changes to song structure relies on LMAN, whereas later expression of maintained changes relies on LMAN-independent components of song motor circuitry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Seventeen adult (>120 days old) Bengalese finches (Lonchura striata domestica) were used in this study. All birds were bred in our colony and housed with their parents until at least 60 days of age. During experiments, birds were isolated and housed individually in sound-attenuating chambers (Acoustic Systems) on a 14:10-h on-off light cycle. All song recordings were of undirected song (i.e., no female was present). All procedures were performed using protocols approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Computerized Song Recording and Control of Reinforcement

Song recording and delivery of experimental stimuli were controlled using EvTAF, a computer program that drives learning through delivery of auditory feedback that is contingent on ongoing song performance (Charlesworth et al. 2011; Tumer and Brainard 2007). For each experiment, a set of spectral templates was constructed that enabled detection of a specific 8-ms segment (the “contingency segment”) within a specific syllable of song (the “target syllable”). To detect the contingency segment, the program continuously monitored successive 8-ms segments of song as they were produced. Detection depended on the spectral structure of song during the contingency segment as well as preceding segments up to 200 ms earlier. A fast-Fourier transform (FFT) was performed on each recorded segment, and the resulting spectrum (power spectral density) was compared against the set of spectral templates. A match to a specific spectral template occurred when the difference between that spectral template and the recorded song spectrum was below a threshold value. Detection of the contingency segment required that a series of 8-ms segments satisfy a prespecified sequence of matches to a set of spectral templates. The template matching sequence was specified so that the contingency time (the midpoint of the contingency segment) occurred within a portion of the syllable in which the harmonic structure was well defined and stable. Across all target syllables, the contingency time, measured relative to syllable onset, had a median value of 38 ms. Detection was temporally precise; the standard deviation of the contingency time (calculated from the empirically measured distribution of contingency times for each syllable) had a median value of 4.5 ms. The variation in the contingency time for a given syllable was due to both random variation in the onset of 8-ms segments relative to syllable onset and also biological variation that affected when song spectral structure matched templates. Across all experiments, the percentage of target syllable renditions that were correctly detected ranged from 98 to 100%. The percentage of non-target syllable renditions that were incorrectly detected as target syllables ranged from 0 to 4%.

After detection of the contingency segment, the FF of the 8-ms contingency segment was computed. This value was compared with a previously set FF threshold. To drive the FF of the target syllable higher, a 60-ms white noise (WN) stimulus was delivered (within 1 ms of the end of the contingency segment) if the calculated FF was below the threshold. To drive FF lower, WN was delivered if the calculated FF was above the threshold.

Trajectories of Learning

Twenty-four distinct multiday learning trajectories (in 15 birds) were driven using WN reinforcement in this study. We first drove a shift in the FF of the targeted syllable during a 3- to 4-day period (e.g., Fig. 2, initial shift). The threshold for reinforcement was initially set so that the hit rate (percentage of syllables receiving WN) was ∼75%. Birds gradually modified FF of the target syllable to lower this hit rate, and the threshold was adjusted daily to propel further learning. For 12 learning trajectories (in 10 birds), the threshold was then fixed to maintain FF at a constant offset from its original baseline value (e.g., Fig. 2, maintained shift). After the period of maintained shift, in 5 experiments (n = 5 birds), reinforcement with WN was terminated to evaluate the extent to which learned changes to FF were retained without external reinforcement. In 5 other experiments (n = 3 birds), recovery of FF toward baseline was initiated by switching the contingency for reinforcement so that the syllables with values of FF closer to baseline escaped WN.

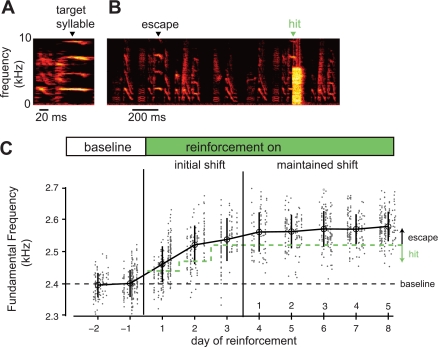

Fig. 2.

Example trajectory of changes to syllable structure driven via a reinforcement learning paradigm. A: spectrogram of the syllable targeted for reinforcement learning. An automated system (Tumer and Brainard 2007) reliably detected a specific time point in the target syllable (inverted black triangle). B: on renditions of the target syllable with a fundamental frequency (FF) below a set threshold, no reinforcement was delivered (escape); on renditions of the target syllable with a FF above the threshold, an aversive reinforcement signal, a 60-ms white noise stimulus (WN), was played over the target syllable (hit). C: example trajectory of learning. During the baseline period (days −2 to −1), no reinforcement was delivered. The mean FF at baseline was 2,400 Hz (open black circles and vertical lines indicate daily mean FF ±1SD). During an initial learning period (initial shift, days 1–3), WN was delivered to syllable renditions with FF below a set threshold (dashed green line). In response to this reinforcement, the values of FF of the target syllable (gray data points) gradually increased. After 2 days of upward shift in FF, the threshold was fixed at 2,520 Hz. In response to this stable reinforcement contingency, the FF of the target syllable stabilized at ∼2,560 Hz, a fixed offset of 160 Hz from baseline. This learned shift in FF was maintained for 5 consecutive days (maintained shift, days 4–8). In this and subsequent figures, a random sample (10–15%) of all songs are displayed and were used to measure syllable FF (see materials and methods).

Reversible Inactivation of LMAN via Retrodialysis

We transiently inactivated LMAN via a retrodialysis technique (Lindefors et al. 1989; Stepanek and Doupe 2010) in which solutes diffuse into targeted brain areas across implanted dialysis membranes. Zero net volume crosses the membrane, making the technique well suited for long-term experiments. In 9 birds, we bilaterally implanted guide cannulas (CMA 7; CMA Microdialysis) by using stereotaxic coordinates. The bird was positioned so that the ventral surface of the upper beak was tipped downward by 40 degrees relative to horizontal. The tips of the cannulas were then positioned 5.3 mm rostral and 1.5 mm lateral to the caudal junction of the midsagittal sinus and transverse sinus and lowered to a depth of 0.7 mm from the surface of the brain. After birds recovered from surgery (3–4 days), we inserted microdialysis probes (CMA 7; 0.24-mm diameter, 1-mm diffusion membrane, 6-kDa diffusion pore size) into the cannulas. Probe tips extended 1.2 mm beyond the guide cannulas so that they were centered in LMAN. Probes were connected to infusion pumps via flexible tubing, a dual-channel liquid commutator (Instech Labs 375/D/22QM), and a fluid switch (BASi Uniswitch) that allowed birds to sing and move around their cage while the solution flowing through the probes was switched remotely. The two probes were connected serially (i.e., the outflow of one probe was the inflow of the second probe).

During control periods, probes were perfused continuously with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; c.f. Stepanek and Doupe 2010). To inactivate LMAN, we remotely switched the dialysis solution to the GABAA agonist muscimol (100–500 μM; Sigma; 7 birds) or the Na+ channel blocker lidocaine (2%; Hospira; 2 birds) at a flow rate of 1 μl/min. Inactivations began 3–5 h after lights were turned on and lasted for 3–4 h, during which a 1 μl/min flow rate was maintained. At the conclusion of the inactivation, the dialyzing solution was switched back to ACSF. Under our experimental conditions, it took 6 min from the time at which solutions were switched at the fluid switch until the new solution reached the tips of both probes. For all analyses and plots, we therefore consider drug infusion (time 0) to begin 6 min after switch of solutions at the fluid switch. Pharmacological inactivations were performed every other day, except for 8 (of 59) cases in which inactivations were performed after a 1-day interval. In several cases (e.g., Fig. 3C), inactivations were not performed until the third day of learning, to elicit a large change in FF before inactivating LMAN.

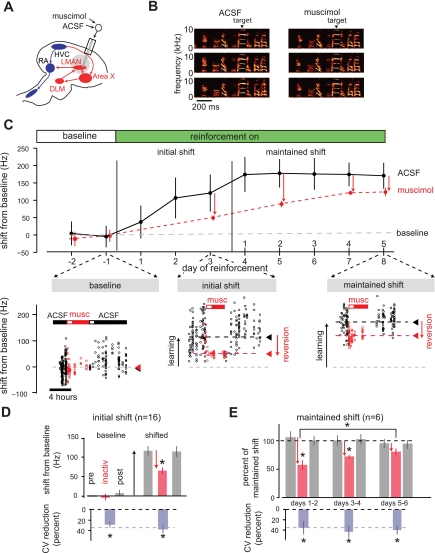

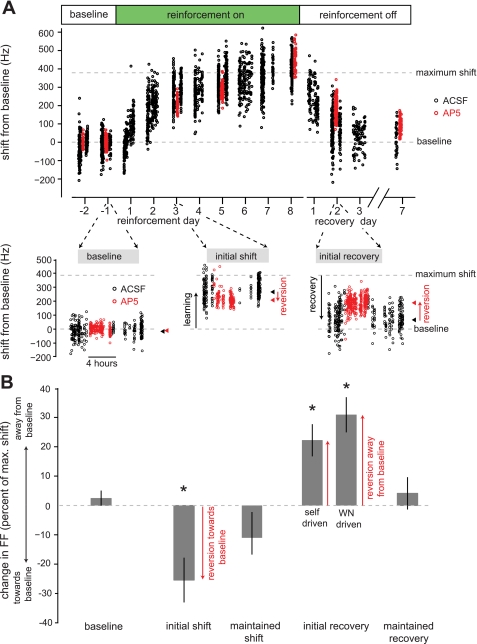

Fig. 3.

Expression of learned changes to syllable structure initially relies on LMAN activity and gradually consolidates to become LMAN independent over multiple days. A: experimental design. Dialysis probes (1 hemisphere shown, sagittal section) were bilaterally implanted into LMAN; retrodialysis solution was switched from a control artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) solution to muscimol, a GABAA agonist, or lidocaine, a Na+ channel blocker. B: spectrograms illustrate preservation of the overall spectrotemporal structure of song following a switch from dialysis of ACSF to dialysis of muscimol. Also shown is the syllable targeted for learning in this experiment (target). C: effects of muscimol retrodialysis during a trajectory of vocal learning. As described in Fig. 2, WN was used to drive a shift in FF of the target syllable during a period of initial learning (initial shift, days 1–3), and then FF was maintained at a fixed offset from baseline (maintained shift, days 4–8 of reinforcement, corresponding with days 1–5 of the maintained shift). Top: mean values of FF during periods of ACSF dialysis (black circles and vertical lines indicate daily mean FF ±1SD) as well as mean values of FF during periods of several hours of dialysis with 200 μM muscimol (red circles and vertical lines). Bottom: expanded time axis with values of FF for individual syllable renditions on 3 specific days: baseline day −1, reinforcement day 3, and reinforcement day 8 (day 5 of maintained shift). Horizontal bars in bottom panel indicate time periods of drug infusions (ACSF, black; muscimol, red); solid bars indicate the period included for analysis, and open bars indicate periods excluded from analysis due to delayed onset of drug effects. Muscimol infusion on day 3 of learning caused a rapid downward reversion of FF toward the original baseline (downward red arrow, reversion). Subsequent muscimol infusions on days 5, 7, and 8 of learning, while the FF was maintained at a learned offset of ∼180 Hz from baseline, caused gradually decreasing reversions. D: summary across all learning trajectories of the effects of inactivating LMAN during the initial shift period. All data are normalized so that positive values indicate shifts of FF in the direction of learning. At baseline, LMAN inactivation caused no significant change in mean FF compared with ACSF pre- and postinactivation periods (baseline; n = 16 experiments in 7 birds; red bars indicate means ± SE for muscimol/lidocaine experiments; gray bars show means ± SE for pre- and postinactivation periods). In contrast, during the initial shift, inactivation of LMAN caused a significant reversion of mean FF toward baseline (mean reversion 46.9%, P < 0.01, 1-tailed t-test). Inactivations of LMAN reduced rendition-to-rendition variability in FF during both the baseline and initial shift periods (bottom, purple bars). For comparison, in this and subsequent figures, the dashed line shows the reduction in coefficient of variability (CV) of FF (34%) reported following lesions of LMAN in adult Bengalese finches from a previous study (Hampton et al. 2009). E: summary effects of disrupting LMAN activity across 6 learning trajectories (n = 4 birds) in which learning was maintained at a stable offset from baseline for at least 5 days. Over this period, the LMAN-dependent component of learning gradually decreased from 45% to 15% while the LMAN-independent component of learning gradually increased. The reduction in variability caused by LMAN inactivations remained stable across these time periods (bottom, purple bars).

We evaluated the efficacy of LMAN inactivations during baseline conditions (before any learning) by measuring the effect of LMAN inactivations on the rendition-to-rendition variability of FF for individual syllables. Previous studies in the adult Bengalese finch and zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) have shown that lesions and inactivations of LMAN cause a reduction in the rendition-by-rendition variability of FF (Andalman and Fee 2009; Hampton et al. 2009; Kao et al. 2005; Stepanek and Doupe 2010). In seven of the nine implanted birds, we observed a significant and reliable reduction in the variability of FF following infusion of muscimol (or lidocaine) into LMAN (P < 0.05 in all seven cases, permutation test; see results). These seven birds were used for subsequent learning experiments; the two remaining birds were perfused and found (via histology; see below) to have incorrect targeting (n = 1) or a faulty dialysis probe (n = 1).

In principle, the effects of infusions could diminish over time, due to either changes in efficacy of dialysis probes or changes induced in LMAN over the course of repeated inactivations. To assess whether this was the case, we monitored for any changes in the influence of LMAN inactivations on the rendition-to-rendition variability of FF over the course of each experiment. We found no trend for a change in the efficacy of LMAN inactivations over the course of experiments (see results). In six birds in which we drove at least two distinct trajectories of learning, we additionally tested for any changes over time in the influence of LMAN inactivations on the expression of learning. In these cases, the first learning trajectory was preceded by only a small number of LMAN inactivations during a baseline period (see above). In contrast, the second trajectory occurred after several weeks during which LMAN was repeatedly inactivated (∼10 prior inactivations of LMAN). There was no significant difference between the effects of LMAN inactivations on the expression of learning for first vs. second trajectories (P > 0.4, paired t-test, n = 6), providing further evidence that neither deterioration of probes nor changes to LMAN function accumulated over time.

Reversible Interference with NMDA Receptors in RA

In five birds, we targeted the song premotor nucleus RA with the same type of cannulas and probes used for LMAN inactivations. RA was mapped electrophysiologically during implantation to direct probes toward the center of the nucleus (see Fig. 4B). RA implants were angled in a posterior direction by 20 degrees relative to LMAN implants to avoid nucleus HVC. During control conditions, ACSF was dialyzed through RA probes. For experimental infusions, the NMDA receptor antagonist dl-AP5 (2–5 mM; Ascent) was dialyzed at a flow rate of 1 μl/min.

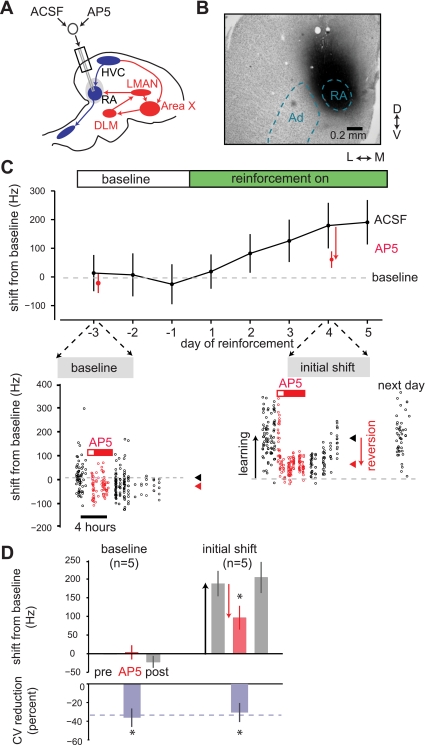

Fig. 4.

Initial expression of learned changes to syllable structure relies on N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation in RA. A: experimental design. Dialysis probes were implanted bilaterally into RA (1 hemisphere shown, sagittal section). dl-AP5, an NMDA-receptor antagonist, was dialyzed across the probes. B: example of drug spread (coronal section). Dark biotin stain shows spread of biotinylated muscimol used to infer drug spread, which encompasses the entirety of RA but not Ad. C: effects of dialysis of AP5 at baseline and during learning. Top: daily mean values of FF during periods of ACSF infusion and interleaved periods of AP5 infusion. Bottom: raw values of syllable FF on baseline day −3 and reinforcement day 4. At baseline, retrodialysis of AP5 caused little change to mean FF. In contrast, retrodialysis of AP5 on day 4 of reinforcement caused a rapid and large (119 Hz) reversion of learned changes to FF. D: summary effects of AP5 infusion during the initial shift period (n = 5 experiments in 5 birds). AP5 dialysis at baseline caused no significant change in FF relative to pre- and post-AP5 ACSF periods (P = 0.8, paired t-test). In contrast, during the initial shift period, AP5 dialysis caused a significant reversion of FF toward the original baseline (P < 0.05, 1-tailed paired t-test). During both periods, AP5 significantly reduced the rendition-to-rendition variability in FF (P < 0.05, 1-tailed paired t-test). Conventions are as described in Fig. 3 legend.

Postexperiment Localization of Dialysis Probes

Probe positioning and the path of drug diffusion were evaluated post mortem by histological staining of sectioned tissue. Tissue damage caused by cannulas enabled confirmation that probes were accurately targeted to LMAN in all seven experimental birds and in RA for all five experimental birds. In addition, in five of the seven birds targeted for LMAN infusion, and in all five birds targeted for RA infusion, biotinylated muscimol (EZ-link biotin kit; Pierce; diluted to 500 μM, matching the highest concentration used across all experiments) was dialyzed across the diffusion membrane for 4 h to estimate the path of diffusion from the membrane (Stepanek and Doupe 2010). In these birds, probe position was determined post mortem by histological staining for biotin and by comparing interleaved sections stained for anti-CGRP [to stain LMAN, medial magnocellular nucleus of anterior nidopallium (mMAN), and Area X; Bottjer et al. 1997; Brainard and Doupe 2001] or for Nissl bodies (RA). In the two remaining birds used for LMAN inactivations, ibotenic acid, an excitotoxic agent, was dialyzed across the membranes at the conclusion of the experiment, and the spatial extent of drug-induced lesions was assessed histologically.

Diffusion paths assessed with biotinylated drug indicated that the radius of maximal spread of drug along the dorsoventral axis of the probe was ∼1.0 mm and that of maximal spread perpendicular to the axis of the probe was ∼0.75 mm. Effects on syllable FF developed within 20 min to 1 h of drug infusion and thereafter remained stable, consistent with prior results indicating that diffusion from a point source results in the gradual development of a stable sphere of drug spread (Amberg and Lindefors 1989; Lindefors et al. 1989).

In experiments targeting LMAN, the sphere of drug spread assessed histologically encompassed the entirety of both LMAN core and LMAN shell. No evidence of drug spread into mMAN was observed. In two of seven LMAN-targeted birds, there was modest drug spread into the most dorsal regions of Area X on at least one side of the brain. The observed effects on variability reduction and the expression of learning in these birds were similar to those observed in other LMAN-targeted birds, and exclusion of these birds did not affect any conclusions about the significance of any reported results. In experiments targeting RA, any drug spread outside RA tended to be in regions dorsal to RA, along the cannula, but not into the lateral areas where Ad is located (see Fig. 4B) (Bottjer and Altenau 2010).

Fundamental Frequency Measurement

FF was measured “online” to determine whether WN would be played back following detection of a target syllable (see above). However, for all analyses presented in results, FF was measured separately off-line so that measurements for a given syllable could be applied to a segment of song that was consistent across all renditions of the syllable. FF was measured for 8- or 16-ms segments of song; for syllables targeted with WN feedback, the segment for which FF was measured was centered at the median point at which feedback was delivered (onset of WN). Previous experiments using the same learning paradigm indicate that any reinforcement-driven changes to FF are likely to be maximal for this portion of the syllable (Charlesworth et al. 2011). We determined FF by calculating the FFT of the sound waveform and measuring peak spectral power via interpolation within a frequency window that spanned the first harmonic or a multiple of the first harmonic (Tumer and Brainard 2007). For each bird, FF was calculated both for the syllable targeted for learning and for a control syllable that did not receive WN. In all birds we analyzed FF in a random selection of songs (10–20%). In some birds, FF was measured for a random subset of “catch” syllables for which WN was omitted during the experiment (as in Tumer and Brainard 2007). In other birds, FF was measured for a random subset of syllables in which a low-pass-filtered WN stimulus was used that allowed measurement of higher frequency harmonics even when WN was played (as in Fig. 2). All analyses were performed with custom software written in MATLAB (The MathWorks).

Assessing Effects of Drug Infusion on Song

In each instance of drug infusion (e.g., muscimol, lidocaine, or AP5), we compared the values of FF for renditions of the target syllable during the experimental infusion with the values of FF during a 4-h control (pre-ACSF) period immediately preceding the infusion. Because of the gradual onset of drug effects, we excluded from analysis the first hour of songs after the dialysis solution was changed (either from ACSF to drug or from drug to ACSF). In one bird, recovery from AP5 infusion took longer than 1 h (e.g., Fig. 4C). In this bird, we analyzed recovery data from the first 2 h of song the morning after drug infusion.

To test whether distinct manipulations (playback of WN, inactivation of LMAN, NMDA receptor blockade) affected the rate of song production, we compared the number of occurrences of the targeted song syllable in a matched 2-h period for each bird during baseline ACSF infusion and during each of the manipulations. For each manipulation, there were no systematic changes in amount of singing relative to that observed during control conditions (ACSF dialysis with no WN), and no manipulation had a significant effect on the rate of production of the target syllable (P > 0.7, paired t-tests).

For analysis of the effects of drug infusions on FF during the initial shift period (e.g., Figs. 3D and 4D, initial shift), the pre-ACSF FF was shifted at least 1.5 SD from the baseline FF distribution and reinforcement had been ongoing for 4 or fewer days. For analysis of the effects of drug infusions during the period when FF was maintained at a fixed offset from its baseline value (e.g., Fig. 3E, maintained shift), the daily median FF offset from baseline was at least 2.5 SD and was maintained within 0.75 SD of the fixed offset value for each of at least 5 consecutive days. During maintained shifts (when the FF remained constant), the effects of drug infusions were compared across each of three periods: days 1 and 2, days 3 and 4, and days 5 and 6. The effects of LMAN inactivation on FF were analyzed relative to the pre-ACSF FF on the day of the inactivation.

During recovery to baseline (see Fig. 6), we compared the effects of blocking input from LMAN to RA across five time stages: 1) baseline, before WN onset, 2) initial shift (defined above), 3) maintained shift (defined above; range of 4–7 days), 4) initial recovery (days 1–3 of recovery), and 5) maintained recovery, in which FF had been restored to within 1 SD of the original baseline level for at least 3 days (3–14 days at baseline in 5 experiments and 43 days at baseline in 1 experiment). For summary analysis in these recovery experiments, we normalized shifts in FF by the magnitude of the maintained offset of FF from baseline (see Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Contributions of LMAN to recovery of syllable structure. A: example effects of AP5 dialysis into RA during self-driven recovery toward baseline. Top: values of FF for individual syllable renditions. Bottom: FF on an expanded time scale for baseline (day −1), initial shift (day 3 of reinforcement), and initial recovery (day 2 following termination of WN). During the initial shift, infusion of AP5 caused a reversion of FF toward baseline, as previously observed. During initial recovery, infusion of AP5 caused a reversion of FF toward the previously maintained level of learning, away from baseline. B: summary effects of blocking LMAN input to RA, via infusion of muscimol in LMAN (n = 6 experiments) or infusion of AP5 in RA (n = 1 experiment), at 5 stages of learning and recovery. Effects are plotted as % change in FF relative to the magnitude of the maintained shift in FF. Interfering with LMAN's input to RA caused a significant reversion toward baseline during the initial shift period (downward red arrow) and a significant reversion away from baseline during the initial recovery period (upward red arrow), both for experiments in which recovery was self-driven (n = 2 experiments; P < 0.01, permutation test with baseline effects) and those in which recovery was WN driven (n = 5 experiments; P < 0.001, permutation test). Values are means ± SE.

In cases where multiple infusions occurred during a given stage of learning (e.g., more than 1 infusion occurred during the initial shift period for a single trajectory of learning), effects were averaged across infusions and contributed only one data point to summary analyses, to avoid pseudoreplication.

Statistics

We used three types of statistical tests: permutation test, t-test, and ANOVA, as described below. The term “significant” refers to results that had P values <0.05. Unless otherwise noted, values are means ± SE.

Permutation test.

We tested for significant differences in test statistics (e.g., mean difference) between unpaired data in two groups via a permutation test in which we tested the null hypothesis that the data from the two groups came from the same underlying distribution. We randomly permuted all data values across the two groups 10,000 times while maintaining the original size of each group. By determining the frequency at which differences in the test statistic in the resampled distributions were as large as the originally observed differences, we generated a P value at which we could reject the null hypothesis that the two groups came from the same underlying distribution.

T-test.

We used paired and unpaired t-tests (as specified in results) to test whether two groups had significantly different means. In cases where we were testing a specific directional hypothesis (e.g., that LMAN inactivation reduced acoustic variability or that LMAN inactivation caused a reversion to the original baseline), we used a one-tailed t-test. These cases are indicated in results.

ANOVA.

We used one-way ANOVA to test for significant differences in the mean across multiple groups in which data were paired (e.g., Fig. 3E). In cases where ANOVA indicated a significant effect, we used a post hoc Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test (which accounts for multiple comparisons) to determine which specific means were significantly different.

RESULTS

Trajectory of Reinforcement-Driven Learning

We used a previously established reinforcement paradigm to elicit adult vocal learning (Fig. 2) (Charlesworth et al. 2011; Tumer and Brainard 2007). An individual target syllable (Fig. 2A) was selected for online monitoring and directed modification. An online, automated system detected each rendition of the target syllable and delivered WN feedback that was contingent on the measured FF for each rendition of the target syllable. In the example in Fig. 2B, feedback was delivered to renditions of the target syllable with FF below a threshold value (“hit”) but not to renditions with FF above that threshold (“escape”). As in previous studies (Andalman and Fee 2009; Charlesworth et al. 2011; Tumer and Brainard 2007), either upward or downward shifts in FF of a target syllable could be directed depending on whether WN was applied to renditions of the target syllable with FF below or above the experimentally imposed threshold.

We used this aversive reinforcement paradigm to drive controlled trajectories of learning to assess contributions of LMAN, and its glutamatergic inputs to RA, at distinct stages of learning. After an initial period of learning during which FF was shifted upward (or downward) by the progressive adjustment of the threshold for reinforcement (Fig. 2C, initial shift), we maintained the learned FF at a fixed offset from baseline by keeping the threshold for reinforcement at a fixed value (Fig. 2C, maintained shift).

Transient Inactivation of LMAN Reverses the Initial Expression of Learning

We first assessed the contributions of LMAN activity to the expression of learning by using bilateral dialysis of either the sodium channel blocker lidocaine or the GABAA agonist muscimol to inactivate LMAN reversibly (Fig. 3A). At baseline, before any learning, inactivation of LMAN had little gross effect on song structure or on the mean FF at which target syllables were sung. An example of this is illustrated in Fig. 3B, which shows spectrograms of song structure during ACSF and muscimol infusions, and in Fig. 3C (baseline period), which shows the mean FF for each day during ACSF (black data points) and muscimol (red data points) infusions (top and bottom panels show daily means and expanded timeline for a single day, respectively). Although there was no significant effect on the mean FF at baseline, there was a significant reduction in the rendition-to-rendition variation in FF, which can be seen as a decrease in the range of FF values at which individual syllables were produced during muscimol infusion [change in mean, P > 0.7; change in the coefficient of variation (CV), P < 0.01, permutation test]. On average, across 16 experiments in 7 birds, inactivation of LMAN at baseline caused no significant shift in mean FF (P = 0.39, paired t-test) but did cause a significant reduction in the CV of FF (28.4 ± 6.0% reduction in CV; P < 0.001, 1-tailed paired t-test; Fig. 3D, baseline). The CV rapidly recovered to its baseline value on subsequent dialysis with ACSF (Fig. 3, C and D). The post-ACSF CV was not significantly different from the pre-ACSF CV (P = 0.25, paired t-test). Such a reduction in variability of syllable structure without other systematic changes to song is consistent with previously reported effects of lesions and inactivations of LMAN in adult zebra and Bengalese finches (Andalman and Fee 2009; Hampton et al. 2009; Kao and Brainard 2006; Kao et al. 2005; Stepanek and Doupe 2010). Indeed, the reduction in CV for FF (28.4%) was not significantly different from that observed following lesions of LMAN in Bengalese finches (34 ± 5%; Fig. 3D, dashed line; data from Hampton et al. 2009; P = 0.52, unpaired t-test). This indicates that infusions of pharmacological agents were effective in inactivating LMAN.

In contrast to the effects of LMAN inactivation at baseline, LMAN inactivation during initial learning caused a large reversion of FF back toward the baseline value of FF. In the example shown in Fig. 3C, by day 3 of learning, the mean FF of the targeted syllable produced under control conditions had been driven upward from the original baseline by 126 Hz. Inactivation of LMAN on day 3 again reduced the variability of FF but additionally caused a significant reversion of the mean FF back toward the original baseline by 72 Hz, or 57% (change in CV, P < 0.001; change in mean, P < 0.001; permutation tests). Across experiments, such a reversion of FF during initial learning (days 2–4 of learning) consistently occurred in response to LMAN inactivation. In all nine experiments in which FF had been shifted upward, inactivation of LMAN caused FF to revert downward; in all seven experiments in which FF had been shifted downward, inactivation of LMAN caused FF to revert upward. The mean reversion of FF toward baseline was 46.9 ± 7.0% (Fig. 3D) and did not differ significantly between experiments in which LMAN was inactivated with lidocaine (43.7 ± 32.9%, n = 3) or muscimol (47.6 ± 5.9%, n = 13; P = 0.84, unpaired t-test). FF rapidly recovered to the learned level on subsequent dialysis with ACSF (Fig. 3, C and D). The post-ACSF FF was not significantly different from the pre-ACSF FF (P = 0.86, paired t-test). The average reduction in the variability of FF for the target syllables in these experiments was 36.5 ± 7.7%, not significantly different from the 28.4 ± 6.0% reduction in variability observed at baseline (P = 0.43, unpaired t-test). The systematic shifts in FF in response to LMAN inactivation were specific to the syllables targeted for learning; the mean FF of control syllables not targeted with WN did not exhibit significant shifts in response to LMAN inactivations during either the baseline or initial shift period (P = 0.7, paired t-test).

These data qualitatively parallel results from Andalman and Fee (2009), who found that infusing the sodium channel blocker TTX to inactivate LMAN in the adult zebra finch caused a reversion of recent learning induced in a similar aversive reinforcement paradigm. Our finding that muscimol, a GABAA agonist, is sufficient to cause such a reversion additionally indicates that the reversion of learning arises from inactivation of cell bodies rather than inactivation of fibers passing through or near LMAN.

Expression of Learning Becomes LMAN Independent via a Slow, Multiday Process

Prior studies suggest that a consolidation process occurs in which the contributions of LMAN to adult plasticity gradually diminish over time (Andalman and Fee 2009; Nordeen and Nordeen 2010). However, the time course of this consolidation process has not been tested directly. In the present study, we tested the time course of consolidation by maintaining learned changes to FF at a fixed offset from baseline and performing successive LMAN inactivations over a period of 5–6 days. An example is illustrated in Fig. 3C (maintained shift). After a period in which FF was directed upward, we maintained FF at a fixed offset of ∼170 Hz from its baseline value for 5 days. We inactivated LMAN on days 2, 4, and 5 of this maintained shift (corresponding to days 5, 7, and 8 since initiation of reinforcement). In this example, the contributions of LMAN activity to the expression of learning gradually declined over the 5-day period of maintained shift in FF. Such a gradual decrease in the contribution of LMAN to the expression of learning was typical during periods of maintained shift. On average (across 6 experiments in 4 birds), during the first 2 days of the maintained shift, LMAN inactivation caused a significant reversion of 45.0 ± 8.2% toward baseline (P < 0.001, 1-tailed paired t-test, Bonferroni corrected for 3 comparisons). After 3–4 days of maintained shift, LMAN inactivation caused a reduced reversion of 27.2 ± 5.1% that was still significant (P < 0.001, 1-tailed paired t-test, Bonferroni corrected), and after 5–6 days caused a further reduced reversion of 15.1 ± 7.1% that did not achieve statistical significance (Fig. 3E, top; P = 0.11, 1-tailed paired t-test, Bonferroni corrected).

These data support two conclusions about consolidation. First, they confirm that learned changes to FF eventually consolidate so that their expression becomes largely independent of LMAN (Andalman and Fee 2009); in particular, we found that over the period in which FF was maintained at a constant value, the magnitude of reversion caused by LMAN inactivation decreased significantly (P < 0.01, ANOVA for difference in mean reversion over time, post hoc Tukey's HSD test for reduced reversion from days 1 and 2 to days 5 and 6, P < 0.05). This decreasing reversion caused by LMAN inactivations could not be attributed to decreasing efficacy of the inactivations, because LMAN inactivations continued to cause a stable reduction in the variability of FF throughout this period (Fig. 3E, bottom; mean reduction of CV across 3 time periods, 40.3 ± 4.6%; ANOVA for difference in CV reduction across these periods, P = 0.6).

Second, in contrast to results of Andalman and Fee (2009), which indirectly suggest that consolidation of learning in a similar paradigm is completed over a single night, our results indicate that consolidation is a gradual, multiday process. Indeed, after 3–4 days over which FF was maintained at a fixed, learned value, 27% of the learned changes to FF remained dependent on LMAN (Fig. 3E). To ensure that this continuing influence of LMAN inactivation on the expression of learning was not due to the recent history of disrupting LMAN activity, we examined a subset of the experiments (n = 4) in which inactivation of LMAN on day 4 of a maintained shift in FF was preceded by at least 2 full days and nights since prior inactivation of LMAN. The reversion of learning in these cases was significant (mean reversion: 23.2 ± 5.0%; P < 0.003, 1-tailed paired t-test). This indicates that consolidation is not fully completed even over a 48-h period in which LMAN remains active.

Initial Expression of Learning Relies on NMDA Receptor Activation in RA

We next tested the hypothesis that LMAN activity contributes to the initial expression of learning via glutamatergic projections from LMAN core to RA, rather than through action of LMAN at its other known targets (Fig. 1) (Bottjer and Altenau 2010; Gale et al. 2008; Johnson et al. 1997; Kittelberger and Mooney 2005; Mooney 2009b). To test the importance of glutamatergic transmission from LMAN core to RA in the expression of learning, we reversibly dialyzed the NMDA receptor antagonist dl-AP5 into RA (Fig. 4, A and B). Since synaptic input from LMAN core to RA is predominantly mediated by NMDA receptors, whereas input from HVC is mediated by a mixture of NMDA and AMPA receptors (Mooney 1992; Mooney and Konishi 1991; Stark and Perkel 1999), blocking NMDA receptors in RA should preferentially block glutamatergic transmission from LMAN to RA while having a lesser effect on transmission within the motor pathway itself (see also Introduction).

Dialysis of AP5 into RA reversed the expression of initial learning in a qualitatively and quantitatively similar manner to LMAN inactivation. An example is shown in Fig. 4C. At baseline, before any learning, dialysis of AP5 significantly reduced the variability in the FF of the target syllable (CV reduction of 47%; P < 0.01, permutation test) while causing little change to the mean FF of the syllable or other aspects of song (Fig. 4C, baseline). However, when the mean FF had been shifted over several days in response to aversive reinforcement with WN, the dialysis of AP5 into RA caused a 66% reversion of FF toward the original baseline (Fig. 4C, bottom, initial shift). Across five experiments in five birds in which AP5 was infused into RA, we observed similar effects on the expression of learned changes to FF. At baseline, there was a significant reduction in the CV of FF (mean reduction of 36.3 ± 9.9%; P < 0.01, 1-tailed paired t-test) but no significant effect on the mean FF (Fig. 4D, baseline; P = 0.8, paired t-test). During initial learning, there was again a reduction in CV, but there was additionally a significant reversion of FF back toward baseline (Fig. 4D, initial shift; P < 0.05, 1-tailed paired t-test). The magnitude of this reversion (46.4 ± 8.8%) was not significantly different from that observed across experiments in which lidocaine or muscimol were infused directly into LMAN (46.9 ± 7.0%; P = 0.9, unpaired t-test).

The similarity of the reversion induced by inactivating LMAN and by blocking NMDA receptors in RA suggests that in both cases reversion occurs because of interference with LMAN core's projections to RA, at either the level of LMAN (in the case of inactivation of LMAN) or the level of RA (in the case of NMDA receptor blockade in RA). In addition, this finding indicates that LMAN-RA glutamatergic release contributes to the initial expression of learning (see discussion).

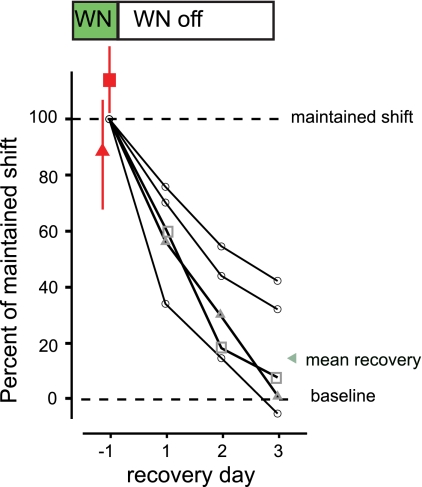

Consolidation Does Not Correspond With the Establishment of Lasting Changes to Song

The contributions of LMAN to the expression of learning gradually wane (Fig. 3E), indicating a process of consolidation in which the expression of learning is transferred to other circuitry. After this consolidation, inactivations of LMAN have only a small effect on the mean FF but still significantly reduce variability of FF, similar to the effects of inactivations at baseline. This similarity raises the question of whether consolidation establishes a new baseline for song structure. If this is the case, then consolidated changes to syllable structure might become engrained so that they are retained even without continued external reinforcement (e.g., Brashers-Krug et al. 1996; Joiner and Smith 2008; Shadmehr and Holcomb 1997). To test this possibility, we turned off WN after maintaining an extended, stable shift in FF and measured subsequent changes to the FF of the target syllable.

After the cessation of WN reinforcement, birds consistently restored the FF of the target syllable back toward the original baseline in a spontaneous, self-driven recovery process. This is illustrated in Fig. 5. For five experiments, contingent reinforcement with WN was first used to drive and maintain a learned shift in FF over a period of 7–15 days. On the basis of our previous experiments (i.e., Fig. 3E), we expected that by the end of this period, the expression of learning would have consolidated so that it no longer greatly depended on glutamatergic transmission from LMAN. We directly confirmed this in two experiments by infusing either muscimol into LMAN (red triangle) or AP5 into RA (red square) on the last day of WN (Fig. 5, day −1). We then turned off WN and monitored subsequent changes to FF that occurred in the absence of external reinforcement (Fig. 5, WN off). In each of the five experiments, FF systematically recovered toward the original baseline value over a period of several days. On average, by the third day following cessation of WN, FF had recovered 84.3% of the way back to the original baseline (Fig. 5, mean recovery). These data indicate that despite the apparent consolidation of learning following prolonged instruction with contingent WN, a new and lasting “baseline” for FF is not established. Rather, there is a stable representation of the original baseline FF and the avian nervous system restores FF back to this baseline via a self-driven process in the absence of continued external instruction.

Fig. 5.

Syllable structure recovers to the original baseline following cessation of reinforcement even after learning has consolidated. Trajectory of syllable FF for 5 birds is shown over the last day (recovery day −1) of a maintained shift in FF driven via WN and over the following 3 days in which no WN was played (WN off; recovery days 1–3). All data are normalized relative to the magnitude of the shift in FF on the last day of the maintained shift (duration of maintained shifts ranged from 4 to 7 days). Two birds were equipped with retrodialysis probes, allowing confirmation that consolidation had occurred by the last day of the maintained shift, so that the expression of learning no longer depended on LMAN (red triangle indicates muscimol infusion in LMAN; red square indicates AP5 infusion in RA; error bars indicate ±1SD). In all 5 birds, following the termination of reinforcement, syllable FF recovered back toward the original baseline over 3 days (recovery days 1–3; gray triangles and squares show recovery trajectories for birds in which consolidation was confirmed with muscimol and AP5, respectively). By day 3, birds had recovered on average 81% of the difference from the original baseline (green triangle, mean recovery).

LMAN Contributes to the Initial Expression of Song Recovery to Baseline

The recovery of FF to the initial prelearning baseline indicates that birds retain a covert representation of the original baseline even following a period of maintained learning in which FF is held at a constant offset from baseline. This covert representation of the baseline FF raises two possible explanations for the effects of LMAN inactivations on the initial expression of learning reported above (Fig. 3). One possibility is that LMAN inactivations always reverse recent learning, whereas another possibility is that LMAN inactivations instead reverse changes to song structure that deviate from the original baseline. To distinguish between these possibilities, we inactivated LMAN during the initial recovery of FF back toward baseline following a period of maintained learning. If LMAN inactivation causes a reversal of differences from the original baseline, then inactivation during recovery should cause FF to shift toward baseline. Alternatively, if LMAN inactivation causes a reversal of recent learning, then inactivation during recovery should cause FF to shift away from baseline, toward the previously maintained value.

Interfering with input from LMAN to RA during recovery consistently shifted FF away from baseline and toward the previously maintained value. An example of this is shown in Fig. 6A. In this experiment, reinforcement with WN was used to drive a shift in FF away from baseline and to maintain changes to FF over an 8-day period (reinforcement on). As shown above (Fig. 4), infusion of AP5 during the initial shift away from baseline caused a reversion of FF back toward baseline (Fig. 6A, reinforcement day 3). The magnitude of this reversion gradually diminished so that on the last day of reinforcement, there was little reversion toward baseline (reinforcement day 8). Reinforcement with WN was then terminated, and the FF of the target syllable gradually recovered back toward the original baseline. On the second day of recovery, at a point when the FF had recovered 81% of the way back to baseline, AP5 infusion resulted in a large shift in FF away from the original baseline and back toward the previously maintained level of learning (recovery day 2). Such a significant shift away from baseline during recovery, toward the level of previously consolidated learning, was observed in two experiments (in 2 birds) in which we tested the effects of LMAN inactivation during spontaneous, self-driven recovery (Fig. 6B, recovery, self-driven; P < 0.01, permutation test relative to baseline effects). We additionally tested the effects of inactivating LMAN during recovery in five experiments (in 3 birds) in which recovery to baseline was not completely spontaneous but was instead propelled by switching the reinforcement contingency so that syllable renditions with FF closer to the original baseline escaped WN. In these cases, too, LMAN inactivation caused FF to shift significantly away from baseline and back toward the previously maintained level of consolidated learning (Fig. 6B, recovery, WN driven; P < 0.001, permutation test relative to baseline effects).

After FF had recovered to the original baseline, there was a gradual “reconsolidation” in the sense that the influence of LMAN inactivations on the mean FF progressively waned. For six of the seven recovery experiments, we tested the effects of inactivating LMAN (or infusing AP5 into RA) after song remained at baseline for at least 3 days (3–14 days at baseline for 5 experiments and 43 days at baseline for 1 experiment). Across these six experiments, after FF had been maintained at the original baseline, inactivating LMAN no longer caused a significant shift in mean FF (Fig. 6B, maintained recovery; P > 0.8, permutation test).

These data indicate that inactivation of LMAN causes a reversion of recent learning, rather than a reversal of differences from the original baseline. Moreover, they indicate that LMAN plays a similar role during learning in which FF is directed away from baseline with external reinforcement and during self-driven recovery without external reinforcement. In both cases, initial changes to song rely on LMAN for their expression, whereas later, maintained changes are subserved by mechanisms that do not require LMAN.

DISCUSSION

In this study we addressed how the cortical analog LMAN contributes to vocal learning in adult Bengalese finches. Consistent with Andalman and Fee (2009), we found that inactivation of LMAN reversed the initial expression of learning in an aversive reinforcement paradigm. We additionally found that blocking NMDA receptors in nucleus RA within the primary song motor pathway reduced the expression of initial learning in a manner that quantitatively matched the effects of inactivating LMAN (Figs. 3 and 4); this indicates that LMAN contributes to the initial expression of learning via direct glutamatergic projections from LMAN core to RA and argues against effects mediated by the influence of LMAN on its other targets (Fig. 1). We found that successive inactivations of LMAN over a multiday period of maintained learning had a gradually decreasing effect on the expression of learning (Fig. 3E), indicating that learning becomes consolidated in circuitry that can operate independently of LMAN. This rules out the possibility that consolidation in this paradigm is completed in a single night and instead suggests that consolidation may gradually develop online during singing. Even after this consolidation, song structure recovered to the original baseline following the termination of reinforcement. This indicates that this form of consolidation does not correspond with a lasting retention of learning (Fig. 5). Finally, we found that LMAN contributed to the initial expression of changes to song during this self-driven recovery process (Fig. 6), indicating that LMAN's role in the expression of adult learning is not limited to aversive reinforcement learning but extends more broadly to other forms of adaptive plasticity.

Mechanisms by Which LMAN Contributes to the Initial Expression of Adult Learning

Both our study (Fig. 3) and prior work by Andalman and Fee (2009) have demonstrated that the expression of initial learning in an adult vocal reinforcement paradigm can be reversed within a period of tens of minutes following the infusion of sodium channel blockers into LMAN. We additionally found that the expression of learning can be reversed by the infusion of muscimol into LMAN (Fig. 3), suggesting that this effect results from inactivation of cell bodies rather than inactivation of fibers passing through or near to LMAN. Our finding that blocking NMDA receptors within RA has a quantitatively similar effect on the expression of learning as inactivating LMAN (Fig. 4) has several additional implications regarding the circuitry and mechanisms by which LMAN activity contributes to the expression of adult vocal learning.

Implications for the Possible Pathways Contributing to the Initial Expression of Learning

We found at baseline that infusions of AP5 into RA reduced rendition-to-rendition variability of adult song, without otherwise disrupting song structure, in a similar manner to lesions or inactivations of LMAN (Fig. 4D, bottom; Andalman and Fee 2009; Kao and Brainard 2006; Kao et al. 2005; Stepanek and Doupe 2010). This suggests that infusions of AP5 into RA achieve a functional deafferentation of RA from its glutamatergic LMAN inputs, without grossly disrupting transmission within the motor pathway (Mooney 1992; Mooney and Konishi 1991; Stark and Perkel 1999). Moreover, because LMAN and the other direct and indirect targets by which LMAN might influence song are spatially distinct from RA (e.g., Fig. 1, Area X, medial striatum, Ad, mMAN, VP, VTA), it is unlikely that infusions of AP5 into RA act directly to alter transmission at these other targets. We found that inactivations of LMAN and infusions of AP5 into RA have quantitatively matched effects on the initial expression of learning (Figs. 3 and 4). Hence, the most parsimonious interpretation of our results is that LMAN contributes to the initial expression of learning via its direct glutamatergic projections to RA.

The finding that local blockade of NMDA receptors in RA can reverse the expression of recent learning is similar to previous findings in other systems in which local blockade of NMDA receptors also reverses the expression of recent learning (Feldman et al. 1996; Fendt 2001; Lee et al. 2001). One interpretation of these prior results is that during learning, local synaptic plasticity creates new local synapses that preferentially rely on NMDA receptor-dependent transmission; according to this possibility, NMDA receptor blockade interferes with the expression of learning mediated by these new local synapses (c.f. Feldman et al. 1996). Our results suggest an alternative possibility; in those prior studies, NMDA receptor blockade could have interfered with the expression of learning mediated by long-range, NMDA receptor-dependent projections from other structures to the site of infusion, as appears to be the case in our experiments.

Implications for the Possible Role of Neurotrophins in the Initial Expression of Learning

Previous work has suggested that neurotrophin release from LMAN to RA might play a critical role in the initial expression of learned changes to song (Akutagawa and Konishi 1998; Johnson et al. 1997; Kittelberger and Mooney 2005, 1999). Neurotrophins are thought to be released from LMAN to RA (Akutagawa and Konishi 1998; Johnson et al. 1997), and in juvenile birds, structural and functional changes to RA following LMAN lesions arise in part due to depletion of this source of neurotrophins (Johnson et al. 1997; Kittelberger and Mooney 1999). In adults, introducing the neurotrophin brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) into RA can drive formation of new synapses from HVC to RA neurons and cause changes to song (Kittelberger and Mooney 2005). Although the time course of the effects of manipulating neurotrophin levels within RA remains unclear, in other systems alteration of neurotrophin levels can affect both electrophysiological and structural measures of synaptic connectivity on a timescale of minutes or even more rapidly (Collin et al. 2001; Kafitz et al. 1999; Kossel et al. 2001; Schuman 1999; Wardle and Poo 2003; Yang et al. 2002). Noteworthy in this respect are studies indicating that removal of neurotrophins can preferentially reverse weaker or more recently formed synapses within minutes (e.g., Berninger et al. 1999). These results suggest that effects of inactivating LMAN on the expression of learning that appear over a period of minutes, as in our experiments and in those of Andalman and Fee (2009), could arise by preventing neurotrophin release into RA; in this scenario, reduced neurotrophin levels might preferentially attenuate or silence newly modified synapses within the motor pathway that contribute to the expression of learning.

Our finding that infusion of AP5 into RA causes similar effects on the expression of learning as silencing LMAN (Fig. 4) argues against a mechanism that relies solely on neurotrophin release. Since the blockade of NMDA receptors in RA is thought to act postsynaptically on RA neurons, it should not alter release of neurotrophins from LMAN into RA. One caveat to this interpretation is that in other systems, blockade of presynaptic NMDA receptors has been shown to affect glutamate release (Bardoni et al. 2004). It therefore remains possible that neurotrophin release into RA could be altered in this way, although such a mechanism has not been reported in the songbird. Likewise, even if AP5 infusion does not block neurotrophin release, possible contributions of neurotrophins to the expression of learning might be prevented by interfering with postsynaptic activity via NMDA receptor blockade (McAllister et al. 1996). Hence, although our results indicate that glutamatergic transmission from LMAN to NMDA receptors in RA is essential for the initial expression of learning, they do not rule out the possibility that neurotrophin release from LMAN to RA also participates in the initial expression of learning or other stages of learning.

How Might LMAN-to-RA Glutamatergic Transmission Contribute to the Initial Expression of Learning?

Our findings and prior results (Andalman and Fee 2009) are compatible with at least two conceptually distinct models whereby glutamatergic transmission from LMAN to RA could contribute to the initial expression of learning. According to an “instructive” or “biasing” model, patterned activity from LMAN directs detailed moment-by-moment changes to RA activity that are responsible for the initial expression of learning. In this model, silencing LMAN causes a reversion of recent learning by removing those structured patterns of activity that are responsible for directing the expression of learning. Consistent with this possibility, LMAN activity is temporally patterned during singing, suggesting that LMAN could provide biasing input to RA that implements changes to song structure at specific time points during song (Hessler and Doupe 1999; Leonardo 2004; Kao et al. 2005, 2008). Moreover, alterations in the pattern of LMAN activity elicited by microstimulation of LMAN in singing birds can acutely implement changes to song structure, including changes to the FF of individual syllables (Kao et al. 2005), demonstrating that alteration of LMAN activity patterns is sufficient to cause real-time changes to song structure.

According to an alternative, but not mutually exclusive, “permissive” or “gating” model, the plasticity that underlies the initial expression of learning resides in the motor pathway itself, and input from LMAN to the motor pathway enables the expression of this plasticity but does not direct the specific changes to RA activity responsible for learning. In this model, silencing LMAN causes a reversion of recent learning by removing neural activity or trophic factors that are required for the expression of plasticity that resides within the motor pathway. Consistent with this possibility, LMAN is tonically active during singing (Hessler and Doupe 1999; Leonardo 2004; Kao et al. 2005, 2008). Therefore, silencing LMAN will remove excitatory drive to RA in a manner that is likely to alter the efficacy of HVC-to-RA (and RA to RA) synapses (Mooney and Konishi 1991; Stark and Perkel 1999). Moreover, theoretical work investigating how LMAN might influence patterns of activity within RA indicates that glutamate release from LMAN onto NMDA receptors in RA is well-positioned to modulate or “gate” transmission at other glutamatergic synapses within RA (Kepecs and Raghavachari 2007). Hence, tonic glutamate release from LMAN might enable the expression of learning-related changes to the patterning of activity in RA without specifically implementing those changes. In this case, the initial expression of learning could rely on changes to connectivity in the motor pathway without necessitating any learning-related changes to the inputs from LMAN (c.f. Mooney 2009b).

Time Course of Consolidation

Our results and those of Andalman and Fee (2009) indicate that learned changes to song structure eventually become consolidated in the sense that the effects of LMAN inactivation on the expression of learning wane over time. This consolidation of learning so that its expression becomes LMAN-independent implies that plasticity eventually develops outside LMAN. Andalman and Fee (2009) drove a trajectory of learning in which the fundamental frequency of a target syllable was constantly changing and therefore did not directly assess how the contributions of LMAN to a fixed amount of learning change over time. However, their results indirectly suggest that consolidation is completed over a single night; when LMAN was inactivated during the day, FF tended to revert to the level sung that morning and no further. In the present study, we maintained learned changes to FF at a fixed value over a period of days so that we could directly determine the time course over which learning consolidates to become LMAN independent. We found that consolidation in our experiments reflects a slow, multiday process and that even after 4 days over which FF was held at a fixed value, a significant amount of learning remained LMAN dependent (Fig. 3E). This finding demonstrates that consolidation in our paradigm is not completed over a single night and instead indicates that consolidation may gradually accumulate online as birds are singing.

The LMAN-dependent component of learning that remains after several days of maintained learning could reflect ongoing but incomplete consolidation. Alternatively, some learning may remain LMAN dependent, regardless of how long learned changes to FF are maintained at a constant value via external reinforcement. Results from our study (Fig. 5) demonstrate that birds retain a capacity and impetus to restore song back to its original baseline structure even after an extended period of maintained learning (c.f. Sober and Brainard 2009; Tumer and Brainard 2007). This suggests that during maintained learning, while FF remains at a constant value, there may be an underlying equilibrium between learning directed away from baseline by external reinforcement and learning directed toward baseline by the bird's own impetus to restore song to baseline. Under these circumstances, there may continue to be ongoing learning, even while FF remains constant. Such ongoing learning during stable behavior, which has been inferred in analogous studies of motor adaptation (Criscimagna-Hemminger and Shadmehr 2008; Sober and Brainard 2009; Tumer and Brainard 2007), could explain LMAN's continuing influence on the expression of learning.

The Consolidation of Learning Does Not Enable the Retention of Learning

We found that consolidation does not correspond with the establishment of a new stable baseline structure of adult song. Rather, there is some covert representation of the original baseline structure that can guide self-driven recovery of song once external reinforcement is removed (e.g., Fig. 5). Previous work suggests that this covert representation may be a stable perceptual target to which the bird restores his song via error corrective learning (Sober and Brainard 2009). The contributions of LMAN to self-driven song recovery (Fig. 6) additionally suggest that this recovery is an active error corrective process, rather than relaxation of the motor system to its prior state. It remains to be determined whether and under what conditions learned changes to adult song can become stabilized in the sense that they are maintained even after external instruction is removed.

Contributions of LMAN to Song Recovery

The effects of inactivating LMAN during song recovery allowed us to distinguish between two alternative explanations for the reversion toward baseline caused by LMAN inactivations (Figs. 3 and 4; Andalman and Fee, 2009). This reversion could occur because inactivating LMAN reverses recent learning or because inactivating LMAN reveals a covert internal representation of the original baseline. Both possibilities (i.e., reversion of learning and return to baseline) are consistent with the finding that during learning in which FF is directed away from baseline, inactivations of LMAN cause a shift in FF toward baseline. However, these possibilities are explicitly distinguished by our experiments in which LMAN is inactivated during recovery of FF to the original baseline after a period of reinforcement-driven learning. In this case, we found that inactivation of LMAN causes a shift in FF away from the original baseline (Fig. 6), inconsistent with the possibility that such inactivation somehow reveals the baseline representation. Rather, this finding indicates that during both reinforcement learning and recovery, LMAN contributes to the initial expression of changes to song.