Abstract

Single pulses of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) result in distal and long-lasting oscillations, a finding directly challenging the virtual lesion hypothesis. Previous research supporting this finding has primarily come from stimulation of the motor cortex. We have used single-pulse TMS with simultaneous EEG to target seven brain regions, six of which belong to the visual system [left and right primary visual area V1, motion-sensitive human middle temporal cortex, and a ventral temporal region], as determined with functional MRI-guided neuronavigation, and a vertex “control” site to measure the network effects of the TMS pulse. We found the TMS-evoked potential (TMS-EP) over visual cortex consists mostly of site-dependent theta- and alphaband oscillations. These site-dependent oscillations extended beyond the stimulation site to functionally connected cortical regions and correspond to time windows where the EEG responses maximally diverge (40, 200, and 385 ms). Correlations revealed two site-independent oscillations ∼350 ms after the TMS pulse: a theta-band oscillation carried by the frontal cortex, and an alpha-band oscillation over parietal and frontal cortical regions. A manipulation of stimulation intensity at one stimulation site (right hemisphere V1-V3) revealed sensitivity to the stimulation intensity at different regions of cortex, evidence of intensity tuning in regions distal to the site of stimulation. Together these results suggest that a TMS pulse applied to the visual cortex has a complex effect on brain function, engaging multiple brain networks functionally connected to the visual system with both invariant and site-specific spatiotemporal dynamics. With this characterization of TMS, we propose an alternative to the virtual lesion hypothesis. Rather than a technique that simulates lesions, we propose TMS generates natural brain signals and engages functional networks.

Keywords: transcranial magnetic stimulation, electroencephalogram, vision

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) studies are often conceived as creating a very fast, focal, and reversible interruption of neural processes at the site of stimulation, effectively disabling neural function or introducing neural noise (Harris et al. 2007), and have been likened to creating a virtual lesion (Amassian et al. 1989; Pascual-Leone et al. 2000). However, evidence inconsistent with this hypothesis demonstrates that the action of TMS is much more complex than simply disabling a region of cortex (e.g., Sack et al. 2006). Brain mapping studies using concurrent imaging techniques (e.g., PET, EEG) have measured responses to the TMS pulse distal from the stimulation site, typically in regions believed to be functionally connected to the stimulation site [functional (f)MRI: Bohning et al. 1998; Baudewig et al. 2001; PET: Fox et al. 1997; Laird et al. 2008; Paus et al. 1997; and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT): Okabe et al. 2003]. For example, TMS over the frontal eye field engages a whole network of brain areas as measured by PET, including regions in occipital and parietal cortex (Paus et al. 1997). Simultaneous EEG measurements have shown TMS-induced brain activity that spreads across cortex very quickly (Paus et al. 2001b) and travels as far as to the opposite hemisphere within 30 ms following stimulation (Ilmoniemi et al. 1997). Thus the action of the TMS pulse at one location apparently engages large-scale cortical networks, not just the focal region that receives the stimulation.

There are a number of mechanisms that determine how TMS engages cortical networks to elicit neural responses. One consideration is the underlying morphology of the stimulation site, which is differentially impacted by the TMS pulse depending on a number of factors. For example, the orientation of the cortical grey matter relative to the coil is one of these factors where the horizontal cells at the fundus of the sulcus and surface of the gyrus (Day et al. 1989) and pyramidal cells in the sulcal wall are thought to be preferentially stimulated (Fox et al. 2004). Further, anisotropy and heterogeneity of the brain tissue underlying the stimulation site can be expected to significantly impact the spatial distribution of the induced electrical field (De Lucia et al. 2007).

Although detailed finite element (FEM) models have been used to estimate the induced electrical field at the stimulation site (Salvador et al. 2010; Silva et al. 2007), such models still do not account for the synaptic interactions of the stimulated neurons within the functional network engaged by the cascade of neural firing following a TMS pulse. The functional connectivity of the stimulation site constrains the excitation to the nodes that are dynamically linked to the stimulation region (Amassian et al. 1998; Ruohonen and Ilmoniemi 1999). A number of EEG studies have measured stimulation site-specific TMS-evoked potentials (TMS-EP) time locked to the TMS pulse onset with, for example, a wave of activity that spreads across cortex, rather than remaining localized to a particular region, following single-pulse TMS-EEG over motor cortex (Bonato et al. 2006). Simultaneous EEG studies have also measured the induced oscillations (i.e., modulations of power of ongoing EEG activity) from single TMS pulses, with resulting transient oscillations apparent in the alpha and beta bands (Fuggetta et al. 2005; Ilmoniemi et al. 1997; Paus et al. 2001a; Rosanova et al. 2009; Van Der Werf and Paus 2006). Thus EEG recordings are consistent with the idea that TMS pulses stimulate other cortical regions with spatiotemporal properties that reflect networks functionally connected to the stimulation site.

In this study, we seek to characterize the spatiotemporal dynamics of visual responses to single TMS pulses using simultaneous EEG recordings. Previous studies investigating functional connectivity within the visual system have limited the regions and measurements used. For example, functional connectivity has been previously investigated, finding visual cortical responses are affected by TMS to frontal and parietal cortical areas (Ruff et al. 2008, 2009). We expand this literature by measuring emergent site-invariant and site-specific networks from visual cortical stimulation. We applied TMS over three functionally distinct visual areas [primary visual areas (V1-V3), motion-sensitive human middle temporal cortex (hMT+), and a ventral temporal (VT) region of each hemisphere], and a single unrelated “control” area (the vertex). Because the behaviorally perceptible impact of TMS is also stimulation intensity specific (e.g., the induction of phosphenes and scotomas, Kammer 1999; Kastner et al. 1998), we also measured the differences observed as a function of stimulation intensity.

Our results show that the evoked potential is dominated by low frequency theta and alpha oscillations (all <12 Hz) and is spectrally similar across stimulation of different areas of the visual system and the vertex. We measured stimulation-site specific (or “local”) responses, distributed mainly over the parietal and occipital cortex in the first 100 ms after stimulation. At longer time scales, we observed theta and alpha oscillations that were globally distributed and spatially similar across stimulation sites. A manipulation of stimulation intensity at one stimulation site (right hemisphere V1-V3) revealed sensitivity to the stimulation intensity at different regions of cortex. Together these results suggest that a TMS pulse applied to the visual cortex has a complex effect on brain function, engaging multiple brain networks functionally connected to the visual system with both invariant and site-specific spatiotemporal dynamics.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Participants

Eight individuals (5 men, 3 women, aged 20–33) participated in both the TMS-EEG and functional (f)MRI portions of the experiment. All observers have normal or corrected-to-normal vision and gave informed, written consent as approved by the University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

fMRI.

Before participating in the TMS-EEG portion of the experiment, subjects participated in an MRI/fMRI session to 1) acquire anatomical images of the individual's brain, and 2) to localize the regions to be stimulated. Averaged fMRI activity and estimated stimulation sites are shown in Fig. 1. Briefly, the early visual areas (V1-V3 region) were identified via a traveling wave analysis (Engel et al. 1994). Subjects viewed 24-s sequences of a high-contrast, contrast-reversing checkerboard wedge (15° wide, 11.1° maximum length) rotating at a rate of 1 cycle every 24 s. The wedge made nine complete rotations within each scan, and each traveling wave scan was repeated twice. Phase-encoding maps were generated by visualizing the lags of the correlated [thresholded at P < 0.05, false discovery rate (FDR) corrected] neural response on the individual's inflated cortical sheet in BrainVoyager (Brain Innovations). The early visual cortex was identified on the basis of meridian border reversals near the right and left occipital pole.

Fig. 1.

Stimulation sites. Head model created from an average MRI from all participants. Functional (f)MRI activity derived from a normalized activity is shown within the sample brain, P < .001, false discovery rate (FDR). Stimulation sites are shown as filled circles. V1-V3, primary visual areas; hMT+, motion-sensitive human middle temporal cortex; VT, ventral temporal region; R, right; L, left.

The VT regions were identified from the same traveling wave analysis as the lateral retinotopically organized brain areas (e.g., Larsson and Heeger 2006) approximately ventral and anterior to the LO-1, LO-2 maps (see Fig. 1 for approximations of the site of stimulation).

The hMT+ was localized as the brain area on the ascending branch of the inferior occipital sulcus that was more activated during 14-s intervals of RDK optic flow motion (randomly switching between inward and outward motion) compared with 14-s intervals of stationary dots. Statistical threshold for significance was set using the FDR as a correction for family-wise error rate (P < 0.01, FDR corrected), which controls the proportion of expected false positives and has the advantage of being adaptive to the signal levels in data while still correcting for multiple comparisons (Genovese et al. 2002).

Finally, the vertex stimulation site was defined by skull landmarks rather than fMRI activity. It was set to the midpoint between the nasion and inion in the anterior-posterior direction, and between the tragus of the left and right ears, as is quite typical in EEG studies.

TMS-EEG.

After the fMRI localization experiments, subjects participated in the TMS-EEG phase of the experiment on a separate day. Stimulation sites were targeted via a frameless stereotaxic guidance system operated in conjunction with Advanced Source Analysis software (Advanced Neurotechnology, The Netherlands). Subjects were seated in a comfortable chair ∼120 cm from the monitor with their heads fixed in a chinrest to minimize movement. A three-pronged axis device was secured to a fixed position on the subject's head and served to register a landmark position (0,0,0), together with fiducial landmarks (tragus of the outer ear, tip of the nose), that identified a coordinate system specific to the subject's head. These landmarks were coregistered to the individual's high-resolution anatomical brain images, which then allows targeting of the desired site of stimulation. The coil position was aligned based on maximizing the overlap between the region of maximum current induction and the localization of visual areas based on fMRI. Coil orientation was determined based on previous psychophysical literature where certain orientations maximally impact performance and create a magnetic field perpendicular to the sulcus of interest (e.g., Amassian et al. 1994; Brasil-Neto et al. 1992; Meyer et al. 1991). For early visual cortex, the coil was oriented parallel to the coronal view (e.g., paddle pointing up), while for MT and VT stimulation the coil was oriented parallel to the midline (e.g., paddle pointing back). These orientations show consistency between behavioral measures used to find these areas and fMRI-guided neuronavigation TMS (Campana et al. 2002; Sack et al. 2006; Schenk et al. 2005; Silvanto et al. 2005). Coil orientation for vertex stimulation was parallel to the axial plane with the paddle pointed back.

For each region, 75 single pulses of stimulation at 55% machine intensity output (E-field, 297 V/m) were applied to each stimulation site, no closer than 4-s apart, parameters that are regarded as safe (Rossi et al. 2009). Because we targeted visual cortex in this study, we used visual phosphenes as a guide for stimulation intensity as opposed to motor responses (as the 2 are not correlated), which has been the standard for several years of TMS-psychophysical investigations (Stewart et al. 2001). Stimulation intensity was set to be ∼80% of the phosphene threshold, based on the subset of subjects that experienced phosphenes when pulsed over early visual cortex (3/8). The remainder of the subjects (5/8) did not experience phosphenes; this is most likely the lower bound of phosphene induction across subjects. All seven regions were collected within two sessions, with the order of stimulation blocked by targeted area randomized across subjects, and subjects wore earplugs to minimize the auditory “click” of the TMS.

Three subjects participated in an additional control experiment with four levels of stimulation intensity of right V1, ranging from 30 to 70% stimulation intensity with corresponding E-field estimates of 162–378 V/m.

Materials

TMS-EEG.

The TMS-EEG experiments were conducted in the TMS/EEG Laboratory in the Human Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of California, Irvine. Stimulation was conducted with a MagStim Model 200 Monophasic Stimulator P/N 3010–00 equipped with a figure-of-eight coil (70 mm, P/N 3190–00). EEG measurements were made with TMS-compatible EEG system (ANT) fitted with a Waveguard cap system using small Ag/AgCl electrodes and a standard 128 channel, high-input impedance amplifier. The EEG signals were recorded with an online average reference and digitized at 1,024 Hz.

fMRI.

Neuroimaging data were collected on a 3T Philips Intera Achieva Magnetic Resonance system located at the University of California, Irvine. Visual displays were projected with a Christie DLV1400-DX DLP projector controlled by a G4 dual-processor Macintosh computer equipped with Matlab (Mathworks) and the Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard 1997; Pelli 1997). Subjects viewed animations used in functional localization of the visual areas via a periscope mirror mounted on an eight-channel birdcage headcoil, directed at a screen positioned behind the subject's head.

For each individual we collected high-resolution (T1-weighted, MPRAGE) whole-brain anatomical images used for coregistration of the functional data. Functional data were collected using single-shot T2*-weighted parallel imaging (SENSE reduction factor R = 1.5; gradient EPI, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 70°, AP phase-encoding, interleaved acquisition) with slices that covered nearly the entire brain (32 ACPC-aligned slices, 1.8 × 1.8 × 4 mm voxels, TR = 20,00 ms).

Analysis

Segmentation.

Raw EEG data (containing the pulse artifact) were subjected to a principal component's analysis for segmentation into epochs for each stimulation site in each subject. The maxima from the largest component of each data set was used to segment each block into 75, 2-s epochs, starting 1 s before pulse. Each trial was normalized by the SD of the 512 samples before the stimulation to standardize variability in EEG amplitudes across recording sessions and subjects. Due to the amplifier artifact introduced by TMS, the 4 samples before the pulse and 16 (15.6 ms) after the pulse were removed from the epochs. Only for visualization, these samples were later replaced with a forward autoregressive moving average prediction of the contaminated data from the intervals directly preceding the TMS pulse and a mild Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter over the interval surrounding the pulse to remove any quick shifts in amplitude due to the artifact editing procedure. Automated artifact editing based on amplitude thresholds was used to eliminate 26 channels likely contaminated with artifacts, leaving 102 channels. Percentiles were calculated for each set of 75 trials for each site and subject. Channels and trials that were beyond the 95th percentile were discarded from the analysis. If a channel contained artifact in half of subjects, this channel was completely removed from the analysis. These measures assured that channels containing artifact from the TMS pulse and high amounts of blink artifact were discarded from the analysis. To avoid any residual artifact including eye blinks and subject movement, median evoked potentials were calculated for each stimulation site, channel, and subject. The evoked potentials were band-pass filtered using a Butterworth filter with 2-dB attenuation at 2 and 40 Hz. A total of 56 recordings of evoked potentials (8 subjects × 7 stimulation sites) was used for further analysis.

ANOVA and correlation analysis.

To determine the regions that are significantly different across stimulation site, the TMS-EP was subjected to a 2 (hemisphere) × 3 (region) ANOVA across subjects, excluding the vertex stimulation site. We also computed an ANOVA separately for each stimulation hemisphere to measure the differences and the homogeneity of each stimulation hemisphere. To quantify the similarity of the TMS-EP between stimulation sites, we calculated the correlation coefficient between the spatial patterns at each time point. Simple effects were also calculated to isolate the regions driving the main effects.

Wavelet analysis.

The majority of spectral power was carried by the evoked power in the TMS-EP, so a continuous wavelet transform of the TMS-EP was calculated with a complex Morlet wavelet with a two-cycle bandwidth for scales between 4 and 40 Hz. The similarity of the spatial pattern of these complex Wavelet coefficients was quantified with a squared correlation coefficient.

Head model creation and deblurring of EEG.

For visualization and source analysis, all anatomical MRIs collected from each individual subject were transformed into a common space (Talairach and Tournoux 1988) and then averaged. Electrode positions were also transformed and then fit to the nearest vertex on the derived head model mesh image. A BEM head model was constructed using the Matlab Toolbox for volume conduction modeling developed at the Helsinki University of Technology (Stenroos et al. 2007). The head model consisted of three ellipsoids fit to the subject averaged, segmented MRI, representing the scalp and inner and outer boundaries of the skull (Srinivasan et al. 2007). The thickness of each layer was uniform across the elliptical surfaces; electrode positions were fit to the scalp ellipse. The use of a uniform thickness skull is essential to avoid generating errors due to thickness variations in the skull layer (Nunez and Srinivasan 2006; Srinivasan et al. 2007). The spatial distribution of the EEG signals was deblurred by using the BEM head model to estimate the potentials on the surface of the brain ellipse following the procedure given by Babiloni et al. (1997). These estimates of cortical potential have been shown to be closely related to surface Laplacian methods (Babiloni et al. 1997; Nunez and Westdorp 1994; Nunez and Srinivasan 2006). Topographic maps show the deblurred EEG map projected (nearest neighbor) to the cortical surface of a single subject's normalized (Talairach and Tournoux 1988) brain. Brodmann areas were then found by finding the peak response within a potential cluster and finding the nearest Brodmann area to that peak. Note that this estimate of cortical potential does not disambiguate sources in adjacent gyral and sulcal surfaces.

RESULTS

TMS-Induced Oscillations and the Resonant Structure of the Recording Site

We applied single pulses of TMS to three functionally dissociated regions of visual cortex (in both hemispheres) and the vertex. Figure 2 shows the resulting TMS-EP at all EEG channels with the channel closest to the stimulation site demarcated in red (using the 10–20 international naming convention, these stimulation sites were closest to electrodes O1/O2, PO5/PO6, PPO9H/PPO10H, and CZ, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Peaks in the transcranial magnetic stimulation-evoked potential (TMS-EP) across stimulation site. Each butterfly plot is the TMS-EP after z-score transformation and artifact editing. Gray rectangles represent the window of the autoregressive moving average correction, and red lines show the EEG response of the electrode closest to the stimulation site (LV1: O1; RV1: O2; LMT: PO5; RMT: PO6; LVT: PPO9H; RVT: PPO10H; vertex: CZ). Inspection of the TMS-EP across stimulation sites, reveals a common osciilation with peaks at 40, 200, and 385 ms, with periodicity ∼150–200 ms. Spatial patterns above the timecourses represent the magnitude distribution across the brain. Transparency of the colormap superimposed onto the brain calculated individually per brain map and scaled by percentile rank.

Several features common across stimulation sites are clearly visible from the time course of the TMS-EP. The TMS-EP shows peaks in the potential at roughly 40, 200, and 385 ms across stimulation sites. In each case, the strongest responses are recorded distal to the electrode closest to the stimulation site. We measured the lowest amplitude oscillations from vertex stimulation. This observation is unsurprising given the localization with skull landmarks rather than functionally significant fMRI activity, likely targeting more heterogeneous regions across subjects.

Considering each of the peak time points in turn, the spatial pattern at the first peak at 40 ms depends strongly on the hemisphere stimulated, with power over occipital and parietal cortex having opposite polarity depending on the stimulated hemisphere. The three stimulation sites (V1, MT, and VT) within each hemisphere show both common areas over occipito-temporal and posterior parietal cortex and distinct areas of response (e.g., over temporal cortex for VT stimulation). In contrast, vertex stimulation shows responses only over the frontal cortex 40 ms following the TMS pulse. The second peak at 200 ms shows a similar spatial pattern to the 40-ms peak (particularly over occipital and parietal cortex) but with opposite polarity and lower magnitude. This reversal is less clear over frontal cortex. The third peak at 385 ms is of even lower magnitude than the prior two and has a spatial pattern much more similar across stimulation sites, with even vertex stimulation showing responses over parietal cortex.

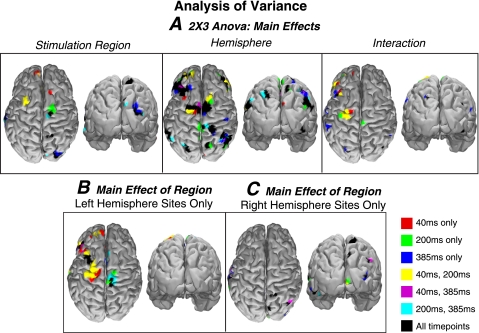

A 2 (hemisphere) × 3 (region) ANOVA across stimulation sites (Fig. 3) shows the regions that exhibit significant differences between stimulation sites at each of the peaks of the TMS-EP (40, 200, and 385 ms). Because of the distinct spatial pattern observed for vertex stimulation, it was excluded in this analysis (although this had little effect on the results). As Fig. 3 shows, regions of the dorsal prefrontal, frontal, parietal, and occipital cortex have a significant main effect of stimulation site (P < 0.05, uncorrected). This is not surprising since MT stimulation of either hemisphere results in a much smaller response at these distal locations. Examining the simple effects of stimulation site across the left hemisphere stimulation sites, we found that the regions of parietal, left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and bilateral frontal cortex are primarily driven by VT stimulation. The main effect of hemisphere (Fig. 3A) reveals a diffuse, widespread effect extending over lateral occipital cortex ventral to the temporal lobe. This widespread dependence on the hemisphere is unsurprising since the polarity of the responses is always positive over the stimulation hemisphere and negative over the other hemisphere at this time point. Of these regions, mainly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and frontal cortex responses showed interaction with stimulation hemisphere. We also calculated an ANOVA restricting each test to one hemisphere of stimulation. These tests (Fig. 3, B and C) show very different regions being significantly modulated by stimulation site depending on the hemisphere stimulated. Left hemisphere stimulation sites show significant differences primarily in the ipsilateral frontal and prefrontal cortex whereas right hemisphere stimulation results in fewer differences largely contained within occipital and parietal cortex. In fact, few areas even reach significance for the right hemisphere only ANOVA, indicating that the effects TMS delivered over right visual cortex have a largely invariant effect (i.e., does not depend on stimulation site). Together, the ANOVA shows 1) the cortical regions most distal to the stimulation sites show the most significant differences between stimulation region and hemisphere of stimulation, 2) right hemisphere stimulation sites engage more spatially similar brain networks than left hemisphere stimulation, 3) V1 and VT stimulation elicit distinct patterns of activity apparently engaging different large-scale cortical networks, and 4) parietal activity is strictly dependent on stimulation hemisphere, not site.

Fig. 3.

ANOVA. A: 2 (hemisphere) × 3 (regions) ANOVA of the z-scored TMS-EP at the three time points of interest in Fig. 2 (40, 200, and 385 ms) showing overlap between significant regions (P < 0.05). Both dorsal and posterior views are shown. Vertex has been excluded to include only effects within the visual networks stimulated. Inspection of the main effect of stimulation region reveals the brain regions significantly modulated by stimulation site. Regions surrounding the vertex and right occipital show significant modulations by stimulation site. A main effect of hemisphere was found in these areas as well as left/right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, portions of parietal cortex, and occipital cortex. Left frontal/motor cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex show a significant interaction between these regions. Separate one-way ANOVA only including the left hemisphere stimulation sites (B) and results for only right hemisphere stimulation (C).

Spatial Correlations Reveal a Site-Invariant Response

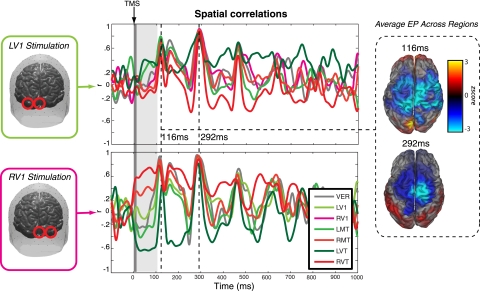

To quantify the spatial similarities between the oscillations evoked at each stimulation site, the spatial pattern of the TMS-EP for each stimulation site was correlated with every other site at each time point. Figure 4 displays the results from this analysis. For convenience, we only show the correlation with the pair of early stimulation sites (LV1/RV1) as these capture the essential effects. Directly after the TMS pulse, within the window containing the first peak of the TMS-EP (40 ms; Fig. 2), the correlations between stimulation sites clearly separate by hemisphere. The evoked response for left hemisphere stimulation is positively correlated with other left hemisphere stimulation sites and negatively correlated with right hemisphere stimulation sites and vice versa for right hemisphere stimulation. Vertex stimulation is uncorrelated with all the other stimulation sites at this time point.

Fig. 4.

Spatial correlations of LV1 and RV1 stimulation. Spatial correlations across stimulation site reveal time windows where the spatial pattern across stimulation sites is highly similar. This occurs at 116 and 292 ms after the TMS pulse. This periodic signal occurs on the rise or fall of the site-specific oscillation (Fig. 2) and is carried by a frontal and posterior occipital network with a negative deflection in the frontal/parietal cortex. Close inspection of the first 100 ms (gray window) reveals the similarity of the spatial pattern to stimulation on the same hemisphere.

These correlation estimates also reveal two time points where the spatial pattern across all stimulation sites are highly similar, maximally at 116 and 292 ms after the TMS pulse, with an average r = 0.82, measured between all possible pairs of stimulation regions. The high correlations fall on the decline of the peaks of the TMS-EP; however, inspection of the source distribution shows that many sources are still reliably higher than baseline EEG (z > 1.96). This site-invariant signal has a periodicity of ∼150–170 ms and is primarily observed within the dorsal parietal/frontal and posterior occipital cortex, with a spatial distribution reminiscent of the P300 evoked potential (Sutton et al. 1965; Basar et al. 1984).

Correlations of Evoked Power

A wavelet analysis was carried out on the TMS-EP to characterize its frequency content within the theta (4–6 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (15–28 Hz), and gamma (30–40 Hz) bands and the correlation between the spatial distributions of wavelet coefficients observed with different stimulation sites. Summed over channels, most of the power of the TMS-EP was found in the theta (69% of total power) and alpha (22% of total power) bands. Correlations were calculated between the complex valued (magnitude and phase) wavelet coefficients, and the results are presented as squared correlation coefficients (r2). Only the theta and alpha bands exhibited significant correlation of the spatial patterns between stimulation sites. Figure 5B shows the power in the theta and alpha to peak shortly (40 ms) after stimulation and decline over the following 700 ms. In contrast, the correlations (Fig. 5A) peak at ∼350 ms for all stimulation sites except VT cortex (both hemispheres). The widespread activity within the first 40 ms following VT stimulation, and the overlap between this network and that of right early visual cortex stimulation, may account for the earlier correlation apparent for the left VT/right VT stimulation (see Fig. 2). Finally, spatial patterns of this oscillatory activity reveal a theta-band oscillation focused in the dorsal parietal/frontal cortex, and an alpha-band oscillation primarily driven by frontal and posterior parietal regions (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Spatial correlations of LV1 and RV1 stimulation of wavelet coefficients for the theta (4–6 Hz) and alpha bands (8–12 Hz). A: spatial correlations across stimulation site reveal a single time window where the spatial pattern across stimulation sites is highly similar for both the theta and alpha bands. This occurs ∼340–360 ms after the TMS pulse for all stimulations sites with the exception of VT. B: summed power across sources reveals this oscillation occurs on the fall of the site-specific evoked power. C: spatial distributions averaged across regions both including and excluding VT stimulation sites. Theta activity is maximal over frontal cortex, and alpha activity is maximal in frontal and posterior cortex.

Differential “Intensity-Tuning” Distal to the Stimulation Sites

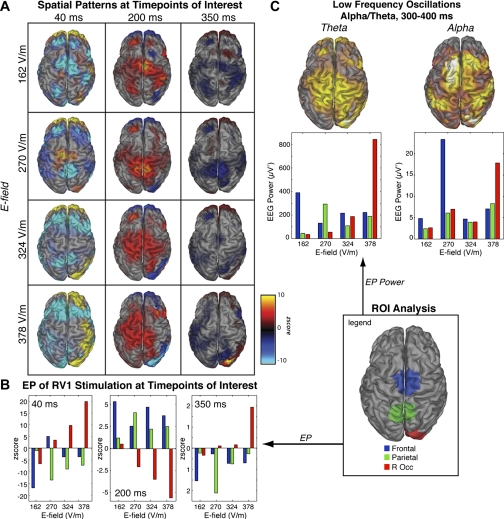

Previous EEG studies have isolated specific components of the TMS-evoked response as being invariant to changes in stimulation (e.g., a result of exposure to an external event rather than injection of current into the brain, per se), with others being modulated by stimulation intensity (e.g., Kahkonen et al. 2005). To test intensity dependence of our observed responses, we have stimulated right hemisphere early visual cortex (RV1) in three subjects and measured the brain response to four different levels of stimulation intensity 30, 50, 60, and 70% machine output, corresponding to an induced electrical field of 162, 270, 324, and 378 V/m. The previously discussed results (Figs. 2–5) were obtained at an intermediate stimulation intensity (297 V/m).

Figure 6A shows the spatial pattern associated with these four levels of intensity. We see large evoked potentials in frontal, parietal, and right occipital cortex at all levels of stimulation. A region of interest (ROI) analysis shows an unexpected intensity-tuning in the evoked response (Fig. 6B). Parietal cortex has the highest response at 270 V/m at all three time points while frontal cortex is actually maximal at the lowest intensity used, 162 V/m. The right occipital ROI, corresponding to the stimulation site, scales monotonically with stimulation intensity, maximizing at 378 V/m (∼70% machine intensity) for all three peaks of the evoked potentials (40, 200, and 350 ms). Of the three ROIs, this is the only region that shows an apparently linear dependence on intensity.

Fig. 6.

Stimulation intensity engages different cortical networks. A: spatial patterns for each stimulation intensity at the time points of interest. Different cortical networks are engaged at different stimulation intensities. B: regions of interest (ROIs) were chosen based on the spatial pattern across stimulation intensities, corresponding to an occipital region at the site of stimulation, a parietal region, and a frontal region. Evoked potential estimate within these ROIs show that some networks scale linearly (occipital, RV1 stimulation), and other regions have an optimal stimulation intensity (parietal/frontal). C: power estimates 300–400 ms after stimulation as measured by wavelet coefficients of the evoked potential.

The spatial maps at the three peaks (Fig. 6A) are consistent with the ROI analysis and also suggest spatial variability with the intensity of stimulation. Finally, we also see this intensity-tuning at the later time window (350 ms) where we observed correlated spatial patterns in the alpha and theta band (Fig. 6C). Occipital cortex is maximally stimulated at the highest stimulation intensity. Parietal theta activity is maximal at 270 V/m while parietal alpha activity shows little variability with intensity. Frontal theta activity is maximal at the lowest intensity (162 V/m), while frontal alpha activity is maximal at 240 V/m.

It is unlikely that these observations could be solely a result of mechanisms unrelated to the effect on the stimulated tissue (e.g., somatosensory experiences related to the pulse, the sound, startle effects, etc.). While the activity near the stimulation site (RV1) is the only ROI that scales linearly with stimulation intensity, all of the other ROIs show responses that depend on stimulation intensity. Together, these results suggest that intensity-tuning may provide another mapping method for the engagement of functional networks distal to the stimulation site.

Induced Oscillations

Band-specific induced power was estimated by calculating the variance of the Fourier coefficients across trials removing the mean evoked potential (Nunez and Srinivasan 2006). A significant increase in the theta range (∼4 Hz) in frontal channels and a decrease in the alpha range (10–12 Hz) of frequencies at parietal channels were present in the induced power estimates for all stimulation regions. However, very few region and channel estimates of induced alpha power reached significance when subjected to a permutation test. It should be noted that previous studies of spectral perturbation (e.g., Rosanova et al. 2009) do not separate the contribution of induced potentials (modulations of ongoing activity) and evoked potentials (time-locked averages). Our findings suggest that most of the effect of the TMS pulse is found in the evoked potential.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study argue for TMS as more than a fast and focal interruption of neural processing at the site of stimulation. Instead, single pulses of TMS impact large-scale cortical networks, eliciting widespread cortical oscillations that persist for hundreds of milliseconds, potentially tracing the functional connectivity of the stimulated region. The oscillations in distal cortical regions saturate at intermediate (parietal) or low (frontal) intensities, suggesting a complex functional interaction within networks connected to the site of stimulation that apparently limit the effect of stimulation intensity within these networks.

The idea of distal and long-lasting oscillations as a result of TMS directly challenges the so-called virtual lesion hypothesis. Previous evidence against this hypothesis has come from simultaneous TMS-EEG studies of motor cortex, showing the propagation of neural activity following a single pulse of TMS (e.g., Bonato et al. 2006; Ilmoniemi et al. 1997; Paus et al. 2001b) or from other concurrent functional neuroimaging studies that measure neural activity in distant brain sites (fMRI: Bohning et al. 1998; Baudewig et al. 2001; PET: Fox et al. 1997; Laird et al. 2008; Paus et al. 1997; and SPECT: Okabe et al. 2003). Our results extend this literature by providing evidence that the time course of the cortical response to a single pulse of TMS is sufficiently long (∼700 ms) to impact multiple cognitive functions and that stimulating one region of cortex has broad impact on a network of brain areas. Critically, by showing that the responses have a complex interaction with stimulation intensity, we argue that our measurements reflect TMS-induced cortical oscillations, rather than endogeneous activity.

Site Specificity of Single-Pulse TMS

TMS induces responses in networks that depend on the stimulation site. The correlation analyses as well as the raw evoked potential showed site-specific and large network oscillations unique for each stimulation site. The implication is that the entire network of brain regions engaged by TMS is dependent on connectivity of that site to the rest of the brain. For visual cortex stimulation, we observed a theta-band oscillation in occipital and parietal cortex, with the specific spatial distribution depending mainly on the hemisphere of the stimulation site. We also observed stimulation over the more VT site to engage additional ventral cortical areas.

Most striking in these findings were the mirrored spatial distributions for stimulation of corresponding cortical sites (e.g., left and right V1) of each hemisphere where the elicited parietal activity was always contralateral to the stimulation site, and this effect is only dependent on hemisphere of stimulation rather than any specific stimulation site in visual cortex. Also, the activity near the site of stimulation was negatively correlated across hemispheres. These oscillations were apparent at 40 ms and had a time course that spans ≥500 ms. The strong hemispheric structure of the observed responses is perhaps not so surprising, since the three nodes of the visual system that we stimulated are heavily interconnected and part of an integrated system with common targets in parietal and frontal cortex.

Interestingly, there were few occipital regions that show significant differences between stimulation sites; the most striking differences may be the comparison between the MT stimulation and VT stimulation. MT stimulation resulted in a very low amplitude response, where VT stimulation resulted in widespread high magnitude responses, especially throughout lateral occipital cortex. hMT+, the human homologue to monkey MT, has been the subject of study for decades, and its response to visual information is determined by several properties of the stimulus, including size, speed, direction, location, and binocular disparity (for review, see Born and Bradley 2005). The VT region, overlapping with the lateral occipital complex, is less clearly mapped. VT cortex is known to be involved in object recognition (e.g., Grill-Spector et al. 2001), visual categorization (Thompson-Schill et al. 1999), and object learning (Op de Beeck et al. 2006). Whereas MT is a relatively small brain area engaged early in perceptual processing, the lateral occipital complex is a large, heterogenous region with a range in tuning to natural objects and invariances to low-level properties of the visual scene. This complexity would imply a need for greater connectivity across the cortex, especially lateral occipital and temporal cortex, as we have observed.

In contrast to the great deal of similarity of the occipital and parietal responses to the three stimulation sites of each hemisphere, we observed frontal and prefrontal responses that depended strongly on the stimulation site primarily driven by responses to VT stimulation. Thus we find evidence of distinct large-scale functional connectivity of VT to distinct frontal and prefrontal targets.

Site-Invariant Networks

The first site-invariant network we observed is the periodic signal suggested by the spatial correlations in Fig. 4. The periodic signal beginning 116 ms after TMS emerges on the fall of the TMS-EP and has a spatial distribution reminiscent of the P300 often observed in visual oddball studies (Sutton et al. 1965); however, the timing of this periodic signal is inconsistent with the P300, which is not repeated, as is shown here at 116 and 292 ms. Instead, this periodic signal is quite unique to TMS. Similar in spatial pattern is the increased power within the theta band observable 300 ms after TMS for all of the stimulation sites (Fig. 5). A stimulation site-invariant alpha oscillation also appeared following the pulse. With the timing alone, it may be suggested that these oscillations could reflect an endogeneous theta/alpha rebound, as typically observed several hundred milliseconds after a visual stimulus following alpha blocking (e.g., Sauseng et al. 2005). However, our intensity varying analysis does not support this interpretation. There is no explanation that would purport an alpha oscillation to peak with an E field of 270 V/m, rather than the highest intensity tested or no variability at all.

The simulation-site invariant responses provide further evidence of the global origins of many scalp EEG signals (Nunez 2000; Nunez and Srinivasan 2006). The cortex is characterized by extensive connectivity by white-matter (corticocortical and callosal) fiber systems that are both specific and diffuse (Braitenberg and Schuz 1991; Nunez 1995). These fiber systems create large-scale neuronal networks, which are believed to give rise to large-scale coherent oscillations such as spatially coherent alpha rhythm, observable over the whole head with EEG electrodes. Mathematical models suggest that these oscillations emerge from the delays imposed by the white-matter connectivity (Nunez 2000; Nunez and Srinivasan 2006) rather than intrinsic properties of the cortical circuits. TMS at one site is propagated to many cortical regions via corticocortical and callosal fiber systems over the cortex and apparently engages global oscillatory modes in theta and alpha bands.

Previous TMS-EEG studies have also found an alpha-band oscillation following TMS to occipital and parietal cortex. Through neural entrainment with repetitive (r)TMS, enhancement of this alpha network has even been found to be behaviorally relevant, modulating visual input processing (Romei et al. 2010) and improving working memory capacity (Sauseng et al. 2009). Single pulses of TMS have also previously been found to elicit alpha activity with occipital stimulation (Rosanova et al. 2009). Our results are consistent with the engagement of these alpha band networks.

Complex Interaction with Stimulus Intensity Suggests Functional Network Responses at Distant Sites

Although previous researchers have used intensity independence as a diagnostic for an endogenous mechanism, other factors such as the sensation of the pulse on the scalp or the auditory evoked response may also linearly scale with intensity. Our results show that brain regions distal to the stimulation site do not have a monotonic response to stimulation intensity. It is known that TMS affects only a subset of neurons at the site of stimulation due to orientation or cycle of the refractory period (Fitzpatrick and Rothman 2000); however, the synaptic interactions are yet unknown. It seems plausible that a change in stimulation intensity increases the probability that electrical current of the induced field will cause an action potential. If a “distant” network connected to the stimulation site is engaged when large assemblies of neurons are active within the stimulation site, then an increase in stimulation intensity will more likely engage this functional network. It should be noted that distant in the brain is actually not very distant at all. It has been shown that a single synapse may reach every other neuron in the brain in relatively few hops or jumps, reminiscent of a small world network (Bassett and Bullmore 2006).

If the probability of a neuron firing increases with stimulation intensity, then this alone would predict that higher stimulation intensity will engage larger networks with an increasing electrical field; however, we also know that the brain has compensatory mechanisms and inhibitory networks that may also be engaged, suppressing some networks and enhancing others. The complex excitation/inhibition interactions within the brain could act as gates, blocking the synthetic visual system response when engaged by a specific stimulation intensity or allowing its spread at another stimulation intensity.

Hemispheric Asymmetries

Interestingly, our results show asymmetries within both the magnitude of the evoked potential (compare left and right VT) and also the ANOVA comparing each region constrained to only one hemisphere, where the right hemisphere stimulation sites appear to be more homogenous than the left hemisphere stimulation sites. While hemispheric asymmetries are the hallmark of several cognitive phenomena (e.g., orienting in spatial attention), we have no a priori reason to expect lateralization in the connectivity from early visual cortex or extrastriate areas of the visual system. Moreover, we found that the resulting oscillations from TMS had more power when applied over the right hemisphere of any given stimulation site. This could reflect higher connectivity of the right hemisphere regions to the rest of the brain compared with the left hemisphere or simply that the anatomical characteristics of the regions stimulated in the left hemisphere were not as optimal (e.g., relative to coil orientation) to elicit the highest response possible. As has been proposed for cortical regions responsible for language comprehension and production, the differences observed could reflect differences in the functional connectivity of left and right visual cortex (Hustler and Galuske 2003).

Implications in psychophysical studies of TMS

It has been known for more than a decade that single pulses of TMS applied to visual cortex may disrupt processing on a particular task (e.g., letter identification, Corthout et al. 1999; motion discrimination, Hotson and Anand 1999). It has also been shown that the time course of such impairments is quite complex (Laycock et al. 2007) and depends on the site of stimulation. Our results speak to these psychophysical investigations of visual processing in several ways. First, it should be noted that these psychophysical studies do not explicitly rely on the virtual lesion hypothesis. Rather than declaring a specific brain region task relevant, we can interpret their findings to declare that brain networks engaged by stimulating the specific brain region are task relevant. While conducting a psychophysical investigation of visual processing, researchers have declared a stimulation region to be task relevant when the behavioral effect is present when stimulating one region over a nonrelevant control region. Our results suggest that the use of vertex stimulation results in an entirely distinct evoked potential that does not engage occipital or parietal cortex for ≥200 ms following stimulation. However, given our results and the high probability of cross-talk between brain regions, it seems unreasonable to perfectly find two nonoverlapping networks in time and space. This suggests that contrasts between stimulation sites that are functionally connected (e.g., V1/VT or V1/MT) are complex to interpret because they engage both common and distinct cortical networks.

Psychophysical research using single-pulse TMS over visual areas of the brain often uncovers multiple windows in time for which TMS impacts performance, both before (>100 ms) stimulus onset and well after (>100 ms) stimulus onset (e.g., Hotson and Anand 1999). In an attempt to understand these temporal dependencies, dynamic theories of visual processing argue that awareness is strongly influenced by the feedback component of visual analysis (e.g., Lamme and Roelfsema 2000). Pascual-Leone and Walsh (2001) hypothesized that the feedforward and feedback processes of visual analysis could be explored by phosphene induction (bright flashes of light induced by TMS over visual cortex). Their results suggest that backprojections from MT to V1 are necessary for awareness of moving phosphenes, and they speculate that reentry of information (Edelman 1989) may be a general principle of visual awareness (Pascual-Leone and Walsh 2001). The correlations shown here, however, would suggest that time points of 40, 200, and 385 ms would have maximal differentiation between stimulation sites and time points corresponding to 116 and 292 ms would have little difference across stimulation sites. Based on the amplitude of the TMS-EP, we would predict the maximal behavioral impact to be very shortly after the pulse, perhaps at 40 ms. On the basis of these findings, we suggest that it may be possible to use both time and space in generation of a psychophysical control for TMS studies. An ideal study to test the reliance of a brain area on a task would have at least two “visual” brain regions (and a vertex control) and two time points of test. With our results, we would predict two sites would produce the common psychophysical effects at 116 ms and may be compared with the results at 40 ms, producing the effect size at the region of task interest that is not a general impact of TMS (116 ms) but still different across sites (40 ms). Future research will assess whether the oscillations found here are behaviorally relevant and align with the multiple time windows of processing these psychophysical studies often report.

Generality of Our Results to Other Stimulation Protocols

Our results have been based on single pulses of TMS from a monophasic coil. It is yet unknown what effects a rTMS or a biphasic coil will have on the TMS-induced oscillations reported here. rTMS sends single trains of TMS pulses very quickly at a region of the cortex. It seems reasonable to speculate, however, that the frequency of the pulse will interact with the global networks reported here in very specific ways and show a significant tuning to rate of stimulation with rTMS. With similar reasoning, rTMS has been paired with a 10-Hz flickering stimulus that entrains neurons and results in a brain response at the flicker frequency (Johnson et al. 2010). These researchers show that rTMS biases task-related activity, interacting with the networks created by neuronal entrainment.

Further, the monophasic coil induces a current in only one direction, while a biphasic coil induces a sinusoidal current. The difference between biphasic and monophasic TMS is becoming increasingly studied (Corthout et al. 2001; Kammer et al. 2001; Niehaus et al. 2000; Arai et al. 2007) but is much more prominent in the rTMS literature. It seems reasonable to assume that a biphasic coil will have effects on the results shown here. It has been shown behaviorally that a monophasic coil has a larger effect on the motor evoked potential than a biphasic coil (Arai et al. 2005). Given the variable responses due to intensity of stimulation as well as region stimulated, it seems likely that a biphasic TMS pulse will also create unknown interactions with the reported networks. Future research is needed to determine the relationship between the local/global oscillations reported here and coil type.

Mechanisms of TMS

A recent surge in publications has attempted to uncover the inter-regional effects of single pulse TMS (Ruff et al. 2006). Most studies that have used concurrent neuroimaging devices have shown a nonlocalized effect of TMS, and our results provide more evidence for this nonlocal interpretation of the mechanism of TMS. We find that TMS engages multiple networks of brain regions in at least two different frequency bands, most likely reflecting the underlying connectivity of that brain region to multiple brain networks. Contrary to common assertions in the application of TMS, the effects of TMS are not very local at all.

Most recently, the virtual lesion hypothesis has been challenged by several researchers who believe TMS is not simply injecting noise into the brain system impacted by the magnetic field but instead traces the resonant frequency of the brain region stimulated (Rosanova et al. 2009). Through inspection of the frequencies >10 Hz within our data, we see consistency with those conclusions where we see that posterior occipital stimulation results in lower frequency activity (∼11 Hz) than vertex stimulation (∼13 Hz); however, since that research did not provide quantitative analysis of the oscillation <10 Hz, we cannot directly speak to the consistency with the relatively low-frequency responses we report here. We also note that their study investigated brain regions that belonged to very different functional networks (occipital, parietal, and frontal) while the purpose of our study was to contrast oscillatory activity elicited by functionally distinct areas of the occipital cortex within the visual system.

Lastly, it is worth noting that the more stimulation site-specific oscillations we measured share some characteristics of a visual-evoked response. Rather than single-pulse TMS creating a virtual lesion, we suggest that TMS is injecting another “stimulus” (consistent with the network engaged) into the brain at specific points in time; this stimulus engages other brain regions to form functional networks.

Conclusions

TMS-induced oscillations trace the multiple functional networks associated with the stimulation site. Robust effects of TMS include global resonances, elicited by any of the stimulation sites we investigated. Together, these findings are in agreement with growing evidence that the “virtual lesion” hypothesis should be revised or abandoned. By targeting a specific brain network, one may use simultaneous neuroimaging or EEG to uncover the functional network of that brain region and the network for which it belongs, researchers may use TMS to track modifications in this network as a function of different cognitive constraints (e.g., attention, visual discrimination) or as a function of disease or aging.

GRANTS

This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health's National Research Service Award F31-EY-019241 (to J. O. Garcia) and Grant RO1-MH-68004 (to R. Srinivasan) and a CORCL grant from the University of California at Irvine (to R. Srinivasan and E. D. Grossman).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Amassian VE, Cracco RQ, Maccabee PJ, Cracco JB, Rudell A, Eberle L. Suppression of visual perception by magnetic coil stimulation of human occipital cortex. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 74: 458–462, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amassian VE, Maccabee PJ, Cracco RQ, Cracco JB, Somasundaram M, Rothwell JC, Eberle L, Henry K, Rudell AP. The polarity of the induced electric field influences magnetic coil inhibition of human visual cortex: implications for the site of excitation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 93: 21–26, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amassian VE, Rothwell JC, Cracco RQ, Maccabee PJ, Vergara M, Hassan N, Eberle L. What is excited by near-threshold twin magnetic stimuli over human cerebral cortex? J Physiol London 506P: 122P–123P, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Arai N, Okabe S, Furubayashi T, Mochizuki H, Iwata NK, Hanajima R, Terao Y, Ugawa Y. Differences in after-effect between monophasic and biphasic high-frequency rTMS of the human motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol 118: 2227–2233, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai N, Okabe S, Furubayashi T, Terao Y, Yuasa K, Ugawa Y. Comparison between short train, monophasic and biphasic repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the human motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol 116: 605–613, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiloni F, Babiloni C, Carducci F, Fattorini L, Anello C, Onorati P, Urbano A. High resolution EEG: A new model-dependent spatial deblurring method using a realistically-shaped MR-constructed subject's head model. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 102: 69–80, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett DS, Bullmore E. Small-world brain networks. Neuroscientist 12: 512–523, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudewig J, Siebner HR, Bestmann S, Tergau F, Tings T, Paulus W, Frahm J. Functional MRI of cortical activations induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Neuroreport 12: 3543–3548, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohning DE, Shastri A, Nahas Z, Lorberbaum JP, Andersen SW, Dannels WR, Haxthausen EU, Vincent DJ, George MS. Echoplanar BOLD fMRI of brain activation induced by concurrent transcranial magnetic stimulation. Invest Radiol 33: 336–340, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonato C, Miniussi C, Rossini PM. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and cortical evoked potentials: a TMS/EEG co-registration study. Clin Neurophysiol 117: 1699–1707, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born RT, Bradley DC. Structure and function of visual area MT. Annu Rev Neurosci 28: 157, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat Vis 10: 433–436, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitenberg V, Schuz A. Anatomy of the Cortex: Statistics and Geometry. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Brasil-Neto JP, Cohen LG, Panizza M, Nilsson J, Roth BJ, Hallett M. Optimal focal transcranial magnetic activation of the human motor cortex: effects of coil orientation, shape of the induced current pulse, and stimulus intensity. J Clin Neurophysiol 9: 132–136, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campana G, Cowey A, Walsh V. Priming of motion direction and area V5/MT: a test of perceptual memory. Cereb Cortex 12: 663–669, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corthout E, Uttl B, Walsh V, Hallett M, Cowey A. Timing of activity in early visual cortex as revealed by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuroreport 10: 2631–2634, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corthout E, Barker AT, Cowey A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation. Which part of the current waveform causes the stimulation? Exp Brain Res 141: 128–132, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day BL, Dressler D, Maertens de Noordhout A, Marsden CD, Nakashima K, Rothwell JC, Thompson PD. Electric and magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex: surface EMG and single motor unit responses. J Physiol 412: 449–473, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lucia M, Parker GJ, Embleton K, Newton JM, Walsh V. Diffusion tensor MRI-based estimation of the influence of brain tissue anisotropy on the effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuroimage 36: 1159–1170, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman GM. The Remembered Present: a Biological Theory of Consciousness. New York: Basic Books, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Engel SA, Rumelhart DE, Wandell BA, Lee AT, Glover GH, Chichilnisky EJ, Shadlen MN. fMRI of human visual cortex. Nature 369: 525, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick SM, Rothman DL. Meeting report: transcranial magnetic stimulation and studies of human cognition. J Cogn Neurosci 12: 704–709, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox P, Ingham R, George MS, Mayberg H, Ingham J, Roby J, Martin C, Jerabek P. Imaging human intra-cerebral connectivity by PET during TMS. Neuroreport 8: 2787–2791, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT, Narayana S, Tandon N, Sandoval H, Fox SP, Kochunov P, Lancaster JL. Column-based model of electric field excitation of cerebral cortex. Hum Brain Mapp 22: 1–14, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuggetta G, Fiaschi A, Manganotti P. Modulation of cortical oscillatory activities induced by varying single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation intensity over the left primary motor area: a combined EEG and TMS study. Neuroimage 27: 896–908, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage 15: 870–878, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Kourtzi Z, Kanwisher N. The lateral occipital complex and its role in object recognition. Vision Res 41: 1409–1422, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AR, Schwerdtfeger K, Luszpinski MA, Sandvoss G, Strauss DJ. Adaptive time-scale feature extraction in electroencephalographic responses to transcranial magnetic stimulation. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2007: 2835–2838, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotson JR, Anand S. The selectivity and timing of motion processing in human temporo-parieto-occipital and occipital cortex: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Neuropsychologia 37: 169–179, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsler J, Galuske RA. Hemispheric asymmetries in cerebral cortical networks. Trends Neurosci 26: 429–435, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilmoniemi RJ, Virtanen J, Ruohonen J, Karhu J, Aronen HJ, Naatanen R, Katila T. Neuronal responses to magnetic stimulation reveal cortical reactivity and connectivity. Neuroreport 8: 3537–3540, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JS, Hamidi M, Postle BR. Using EEG to explore how rTMS produces its effects on behavior. Brain Topogr 22: 281–293, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahkonen S, Komssi S, Wilenius J, Ilmoniemi RJ. Prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation produces intensity-dependent EEG responses in humans. Neuroimage 24: 955–960, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammer T. Phosphenes and transient scotomas induced by magnetic stimulation of the occipital lobe: their topographic relationship. Neuropsychologia 37: 191–198, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammer T, Beck S, Erb M, Grodd W. The influence of current direction on phosphene thresholds evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 112: 2015–2021, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner S, Demmer I, Ziemann U. Transient visual field defects induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation over human occipital pole. Exp Brain Res 118: 19–26, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird AR, Robbins JM, Li K, Price LR, Cykowski MD, Narayana S, Laird RW, Franklin C, Fox PT. Modeling motor connectivity using TMS/PET and structural equation modeling. Neuroimage 41: 424–436, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamme VA, Roelfsema PR. The distinct modes of vision offered by feedforward and recurrent processing. Trends Neurosci 23: 571–579, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson J, Heeger DJ. Two retinotopic visual areas in human lateral occipital cortex. J Neurosci 26: 13128–13142, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laycock R, Crewther DP, Fitzgerald PB, Crewther SG. Evidence for fast signals and later processing in human V1/V2 and V5/MT+: a TMS study of motion perception. J Neurophysiol 98: 1253–1262, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BU, Diehl R, Steinmetz H, Britton TC, Benecke R. Magnetic stimuli applied over motor and visual cortex: influence of coil position and field polarity on motor responses, phosphenes, and eye movements. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl 43: 121–134, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus L, Meyer BU, Weyh T. Influence of pulse configuration and direction of coil current on excitatory effects of magnetic motor cortex and nerve stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 111: 75–80, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez PL. Toward a quantitative description of large-scale neocortical dynamic function and EEG. Behav Brain Sci 23: 371–398; discussion 399–437, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez PL. Neocortical Dynamics and Human EEG Rhythms. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Nunez PL, Westdorp AF. The surface Laplacian, high resolution EEG and controversies. Brain Topogr 6: 221–226, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez PL, Srinivasan R. Electric Fields of the Brain: the Neurophysics of EEG. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Okabe S, Hanajima R, Ohnishi T, Nishikawa M, Imabayashi E, Takano H, Kawachi T, Matsuda H, Shiio Y, Iwata NK, Furubayashi T, Terao Y, Ugawa Y. Functional connectivity revealed by single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) during repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol 114: 450–457, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Op de Beeck HP, Baker CI, DiCarlo JJ, Kanwisher NG. Discrimination training alters object representations in human extrastriate cortex. J Neurosci 26: 13025–13036, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A, Walsh V. Fast backprojections from the motion to the primary visual area necessary for visual awareness. Science 292: 510–512, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A, Walsh V, Rothwell J. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in cognitive neuroscience–virtual lesion, chronometry, and functional connectivity. Curr Opin Neurobiol 10: 232–237, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Castro-Alamancos MA, Petrides M. Cortico-cortical connectivity of the human mid-dorsolateral frontal cortex and its modulation by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Eur J Neurosci 14: 1405–1411, 2001a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Jech R, Thompson CJ, Comeau R, Peters T, Evans AC. Transcranial magnetic stimulation during positron emission tomography: a new method for studying connectivity of the human cerebral cortex. J Neurosci 17: 3178–3184, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Sipila PK, Strafella AP. Synchronization of neuronal activity in the human primary motor cortex by transcranial magnetic stimulation: an EEG study. J Neurophysiol 86: 1983–1990, 2001b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat Vis 10: 437–442, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romei V, Gross J, Thut G. On the role of prestimulus alpha rhythms over occipito-parietal areas in visual input regulation: correlation or causation? J Neurosci 30: 8692–8697, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosanova M, Casali A, Bellina V, Resta F, Mariotti M, Massimini M. Natural frequencies of human corticothalamic circuits. J Neurosci 29: 7679–7685, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual-Leone A. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol 120: 2008–2039, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff CC, Blankenburg F, Bjoertomt O, Bestmann S, Freeman E, Haynes JD, Rees G, Josephs O, Deichmann R, Driver J. Concurrent TMS-fMRI and psychophysics reveal frontal influences on human retinotopic visual cortex. Curr Biol 16: 1479–1488, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff CC, Bestmann S, Blankenburg F, Bjoertomt O, Josephs O, Weiskopf N, Deichmann R, Driver J. Distinct causal influences of parietal versus frontal areas on human visual cortex: evidence from concurrent TMS-fMRI. Cereb Cortex 18: 817–827, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff CC, Blankenburg F, Bjoertomt O, Bestmann S, Weiskopf N, Driver J. Hemispheric differences in frontal and parietal influences on human occipital cortex: direct confirmation with concurrent TMS-fMRI. J Cogn Neurosci 21: 1146–1161, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruohonen J, Ilmoniemi RJ. Modeling of the stimulating field generation in TMS. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl 51: 30–40, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack AT, Kohler A, Linden DE, Goebel R, Muckli L. The temporal characteristics of motion processing in hMT/V5+: combining fMRI and neuronavigated TMS. Neuroimage 29: 1326–1335, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador R, Silva S, Basser PJ, Miranda PC. Determining which mechanisms lead to activation in the motor cortex: A modeling study of transcranial magnetic stimulation using realistic stimulus waveforms and sulcal geometry. Clin Neurophysiol 122: 748–758, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauseng P, Klimesch W, Stadler W, Schabus M, Doppelmayr M, Hanslmayr S, Gruber WR, Birbaumer N. A shift of visual spatial attention is selectively associated with human EEG alpha activity. Eur J Neurosci 22: 2917–2926, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauseng P, Klimesch W, Gerloff C, Hummel FC. Spontaneous locally restricted EEG alpha activity determines cortical excitability in the motor cortex. Neuropsychologia 47: 284–288, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk T, Ellison A, Rice N, Milner AD. The role of V5/MT+ in the control of catching movements: an rTMS study. Neuropsychologia 43: 189–198, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S, Basser PJ, Miranda PC. The activation function of TMS on a finite element model of a cortical sulcus. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2007: 6657–6660, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvanto J, Lavie N, Walsh V. Double dissociation of V1 and V5/MT activity in visual awareness. Cereb Cortex 15: 1736–1741, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan V, Eswaran C, Sriraam N. Approximate entropy-based epileptic EEG detection using artificial neural networks. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed 11: 288–295, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenroos M, Mantynen V, Nenonen J. A Matlab library for solving quasi-static volume conduction problems using the boundary element method. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 88: 256–263, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LM, Walsh V, Rothwell JC. Motor and phosphene thresholds: a transcranial magnetic stimulation correlation study. Neuropsychologia 39: 415–419, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton S, Braren M, Zubin J, John ER. Evoked-potential correlates of stimulus uncertainty. Science 150: 1187–1188, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain: 3-Dimensional Proportional System: an Approach to Medical Cerebral Imaging. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Schill SL, Aguirre GK, D'Esposito M, Farah MJ. A neural basis for category and modality specificity of semantic knowledge. Neuropsychologia 37: 671–676, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Werf YD, Paus T. The neural response to transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. I Intracortical and cortico-cortical contributions. Exp Brain Res 175: 231–245, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziehe A, Laskov P, Muller KR, Nolte G. A linear least-squares algorithm for joint diagonalization. In: 4th International Symposium on Independent Component Analysis and Blind Signal Separation (ICA 2003) Nara, Japan: 2003, p. 469–474 [Google Scholar]