Abstract

The role of primary motor cortex (M1) in the control of voluntary movements is still unclear. In brain functional imaging studies of unilateral hand performance, bilateral M1 activation is inconsistently observed, and disruptions of M1 using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) lead to variable results in the hand motor performance. As the motor tasks differed qualitatively in these studies, it is conceivable that M1 contribution differs depending on the level of skillfulness. The objective of the present study was to determine whether M1 contribution to hand motor performance differed depending on the level of precision of the motor task. Here, we used low-frequency rTMS of left M1 to determine its effect on the performance of a pointing task that allows the parametric increase of the level of precision and thereby increase the level of required precision quantitatively. We found that low-frequency rTMS improved performance in both hands for the task with the highest demand on precision, whereas performance remained unchanged for the tasks with lower demands. These results suggest that the functional relevance of M1 activity for motor performance changes as a function of motor demand. The bilateral effect of rTMS to left M1 would also support the notion of M1 functions at a higher level in motor control by integrating afferent input from nonprimary motor areas.

Keywords: interhemispheric inhibition

the role of primary motor cortex (M1) in the control of voluntary hand movements is still unclear. In functional MRI studies of unilateral hand motor performance, strictly contralateral M1 (cM1) activation is demonstrated by some investigators (Butefisch et al. 2005; Catalan et al. 1998), whereas bilateral M1 activation is observed by others (Hummel et al. 2003; Lotze et al. 2006; Seidler et al. 2004; Winstein et al. 1997). There are more recent reports of a relationship between the level of precision or complexity of a motor task and this additional ipsilateral M1 (iM1) activation (Hummel et al. 2003; Seidler et al. 2004; Verstynen et al. 2005). These results suggest that the functional relevance of iM1 activity for motor performance changes as a function of difficulty of a motor task. These findings are consistent with the more recent evidence of bilateral M1 projections from posterior parietal (Koch et al. 2008, 2009) and dorsal premotor areas, likely conveying some task-related information such as visuospatial and motor planning information. It would support the notion that M1 functions at a higher level in motor control by integrating afferent information and then generating a descending motor command that defines the spatiotemporal form of the movement (Kalaska 2009). Furthermore, if one M1 is or its corticospinal projections are injured as in stroke to one hemisphere, the role of M1 in the nonaffected hemisphere in the motor control of hand movements may change (Hummel et al. 2008).

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has been used as a means to probe the role of M1 in motor performance. Low-frequency rTMS (1 Hz or less) at intensities at about motor threshold (MT) applied to M1 can be used safely (Wassermann et al. 1998) to decrease excitability in the stimulated M1 (Bagnato et al. 2005; Chen et al. 1997; Di Lazzaro et al. 2008; Fitzgerald et al. 2006; Maeda et al. 2000b; Sommer et al. 2002). Low-frequency rTMS of one M1 can also lead to effects remote from the stimulated cortex. For example, subthreshold 1-Hz rTMS applied to one M1 suppressed intracortical inhibition and enhanced intracortical facilitation in the opposite, nonstimulated M1 (Kobayashi et al. 2004). Furthermore, changes in metabolic rate in the contralateral motor cortex or increases in the coherence between the motor cortices or between stimulated cortex and more anterior motor areas have been reported (Strens et al. 2002). These corticocortical and interhemispheric effects may lead to changes at the behavioral level. For example, improved performance of the hand ipsilateral to the stimulated M1 was reported by some investigators (Dafotakis et al. 2008; Kobayashi et al. 2003). As the functional relevance of M1 activity for motor performance may change as a function of difficulty of a motor task, it is conceivable that the rTMS-related behavioral effects differ depending on the level of difficulty of a motor task. In previous experiments, only qualitatively different movements were studied (Chen et al. 1997; Dafotakis et al. 2008; Kobayashi et al. 2004). The objective for the present study was to determine whether the effect of low-frequency rTMS of M1 on performance of the hand differs depending on the level of precision of the motor task.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview of the Experimental Plan

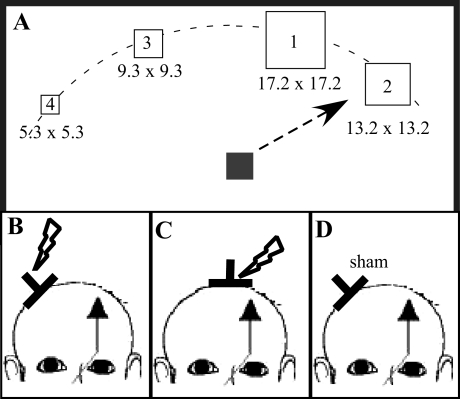

Three experiments were carried out to determine the effect of low-frequency rTMS of M1 (Kobayashi et al. 2004) on accuracy and speed in an increasingly demanding parametric hand motor task with equal number of limbs moved, equal number of movements, and equal number of trajectories but different target sizes (experiment 1; Fig. 1, A and B). The effect of this stimulation on motor performance was compared with two control conditions (experiments 2 and 3; Fig. 1, C and D). In experiment 2, rTMS was applied to the vertex to control for site of stimulation. In experiment 3, sham stimulation was applied to the M1 to control for the effect of rTMS. The order of the experiments was randomized and separated from each other by >24 h. Subjects were blinded to the purpose of the stimulation. Because there is some evidence that the level of intracortical excitability (short interval cortical inhibition, SICI) (Daskalakis et al. 2006) and interhemispheric inhibition (IHI) (Gilio et al. 2003) predict or mediate rTMS-related effects on M1 or cM1, we conducted an additional experiment (experiment 4) to demonstrate presence of IHI and SICI in the middle-aged population (see below). The relationship between these baseline measures and rTMS-related behavioral effects was explored. All experiments were approved by the ethics committee of West Virginia University and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All studied subjects gave their written informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup. A: before and following the stimulation, subjects had to manipulate a joystick in a pointing task with either the left or right hand. Subjects were asked to move a cursor (6.6 × 6.6 mm) as quickly as possible to the center of targets of different sizes on their appearance on the screen. Once located in the center of the target, subjects were asked to push a response button located on the top of the joystick. Targets were presented every 3.5 s at 4 evenly spaced locations on the upper half field of a personal computer (PC) monitor (30, 60, 300, and 330°). Targets were of varying sizes [5.3 × 5.3 mm (target 4), 9.3 × 9.3 mm (target 3), 13.2 × 13.2 mm (target 2), and 17.2 × 17.2 mm (target 1)]. B–D: the effect of 1-Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) at 90% resting motor threshold (MT) to ipsilateral primary motor cortex (iM1; B) and vertex (C) was tested. In an additional control condition, sham rTMS was applied to iM1 (D).

Subjects

Because the information expected to be gained from these data are also important for the understanding of motor control in the diseased brain such as after stroke, and age impacts processes involved in motor control (Mattay et al. 2002; Ward and Frackowiak 2003), the middle-aged population was selected for the present study. Twelve subjects (9 females and 3 males, age 55.00 ± 11.34 yr) fulfilled the following inclusion criteria and were included in this study: age > 40 yr, normal MRI of the brain, normal neurological examination, no neurological disorder, no contraindication for TMS or MRI, and no intake of central nervous system-active drugs. All subjects were right-handed according to the Edinburgh inventory for handedness (Oldfield 1971). Normality of the brain was confirmed by structural MRI of the brain (see below for details).

Motor Task

Before and following TMS (see below), subjects had to manipulate a joystick in a pointing task with either the left or right hand. The joystick was firmly attached to a “bed-table” that rested on the subject's lap. For the performing hand, the forearm and wrist rested on the table and were supported by cushions, whereas the hand was free to manipulate the joystick. This ensured a standardized manipulation strategy across subjects. The nonperforming arm rested on the table.

We chose a pointing task that allowed the parametric increase of the level of difficulty by decreasing the size of the target. Decreasing the target size increases the level of difficulty, which results in longer movement times, known as the speed-accuracy tradeoff described in Fitts' law (Fitts 1954). Restricting the response time to a short, predefined period also will result in less accuracy. Real-time feedback of the joystick position was provided by a cursor moving on a computer screen. Subjects were asked to move the cursor as quickly as possible to the center of targets of different sizes immediately on their appearance on the screen. Once the cursor was in the center of the target, subjects were asked to push a response button located on the top of the joystick. Targets were of varying sizes [5.3 × 5.3 mm (target 4), 9.3 × 9.3 mm (target 3), 13.2 × 13.2 mm (target 2), and 17.2 × 17.2 mm (target 1)]. A maximum time of 2 s was given to perform the task. The size of the targets and the length of the time interval were determined during the design and testing of the pointing task with that particular joystick to achieve an accuracy of >50% (>5/10 trials) for the smallest target and an accuracy of ∼90% for the largest target. Since rTMS of M1 can produce either impaired or improved accuracy, the selected size of the targets would capture changes in performance in either direction. After each trial, subjects were given feedback about their performance. If the subject moved the cursor to the center of the target within the allotted time, the word “hit” was displayed. If the subject failed to hit the center of the target within the allotted time, the word “miss” was displayed. After the display of the feedback (0.5 s), subjects were asked to move the cursor back into a central position on the display screen. Targets were presented every 3.5 s at 4 evenly spaced locations on the upper half field of a personal computer (PC) monitor (30, 60, 300, and 330°; Fig. 1A). The different locations and sizes were displayed in random order. Subjects' performance on this task was tested for the left and right hands separately in 2 blocks of ∼6 min. In each block, subjects performed 20 trials for each target size. Testing was performed before and immediately after the different interventions. The order of the tested hand was randomized across subjects and within each experiment.

The experiments were performed under the control of the Presentation software. Performance time and correct or incorrect position of the cursor in reference to the target were stored on the PC for offline data analysis.

All subjects practiced the motor task with both the left and right hands at least 1 day before the first experiment to achieve a stable performance on all targets and an accuracy of >50% on the smallest target.

MRI of the Brain

High-resolution anatomic images were collected on a 3T GE scanner (General Electric) with the following parameters: SPoiled Gradient Recalled (SPGR); field of view = 240; matrix = 256 × 256; slice = 1.5 mm; 124 slices. The MRI of the brain was reviewed for possible structural abnormalities. Once anatomic normality of the brain was established, the MRI of the brain was reconstructed in Brainsight (Rogue Research, Montréal, Québec, Canada) and served as each subject's reference for the coil position across experiments and within each experiment.

TMS Measures of Intracortical Inhibition and IHI

Subjects were comfortably seated in a dental chair surrounded by a frame that carried a coil holder to assist with the application of TMS to the brain (Brainsight; Rogue Research). Surface electromyographic (EMG; band pass = 1 Hz to 1 kHz) activity was recorded from the target muscle [right and left first dorsal interosseous muscle (FDI)] using surface electrodes (11-mm diameter) in a belly-tendon montage and a data acquisition system (LabVIEW; National Instruments). TMS was applied through a figure-of-8-shaped coil (7-cm wing diameter) using 2 Magstim 200 stimulators (Magstim). The coil was positioned on the scalp over the left or right M1 at the optimal site (hot spot) for stimulating the corresponding contralateral FDI muscle. At the optimal site, the resting MT, defined as the minimum stimulus intensity to evoke a motor evoked potential (MEP) of >50 μV in at least 5 of 10 trials (Rossini et al. 1994), was determined to the nearest 1% of maximum stimulator output (MSO). The position was marked on the subject's MRI of the brain for future reference using the navigation system Brainsight.

IHI at Baseline

For the measurements of IHI, 2 Magstim 200 stimulators (Magstim) were used. With the subjects at rest, a conditioning pulse (CS) was applied to the optimal scalp position of the M1 of either hemisphere to stimulate the corresponding contralateral FDI using a figure-of-8 coil (70-mm diameter) (Ferbert et al. 1992). The intensity of CS was adjusted to produce a MEP of ∼1.5 mV (Ferbert et al. 1992). A test pulse (TS) was applied to the homotopic area of the opposite hemisphere, defined as optimal scalp position to stimulate the contralateral FDI using a smaller figure-of-8 coil (50-mm diameter). The usage of the smaller coil was necessary to accommodate both stimulating coils on the subject's skull. The intensity of the TS was adjusted to produce a MEP of ∼1.5 mV (Ferbert et al. 1992). Ten paired pulses were applied at interstimulus intervals (ISIs) of 2, 8, and 10 ms (30 paired pulses) and intermixed with 10 single TS and 10 single CS. Pulses were applied at random.

SICI at Baseline

SICI was measured using paired-pulse TMS at an ISI of 2 ms. The intensity of the CS varied between 30 and 80% of MT and was administered randomly (Butefisch et al. 2003, 2008), whereas the intensity of TS remained constant at 120% of the MT. Because inhibitory and excitatory circuits are stimulated simultaneously, varying the intensity of the CS allows the study of the threshold and excitability of inhibitory and excitatory activity in more detail (Butefisch et al. 2003, 2008; Chen et al. 1998; Schafer et al. 1997). Paired pulses (5 pairs at each CS intensity) were intermixed with single TS and CS (5 of each) and administered randomly to M1 of either left or right hemisphere. The sequence of timing of stimuli was controlled by customized software. TMS was applied through a figure-of-8-shaped coil (7-cm wing diameter) using 2 Magstim 200 stimulators connected via a BiStim module (Magstim).

Low-Frequency rTMS and Sham Stimulation

Subjects were comfortably seated in a dental chair surrounded by a frame that carried a coil holder to assist with the application of TMS to the brain (Brainsight; Rogue Research). Surface EMG (band pass = 1 Hz to 1 kHz) activity was recorded from the target muscle [right extensor carpi ulnaris muscle (ECU)] using surface electrodes (11-mm diameter) in a belly-tendon montage and a data acquisition system (LabVIEW; National Instruments). TMS was applied through an air-cooled figure-of-8-shaped coil (7-cm wing diameter) using the rapid Magstim 2002 (Magstim). The coil was positioned on the scalp over the left M1 at the optimal site (hot spot) for stimulating the right ECU. At the optimal site, the resting MT, defined as the minimum stimulus intensity to evoke an MEP of >50 μV in at least 5 of 10 trials (Rossini et al. 1994), was determined to the nearest 1% of MSO. The position was marked on the subject's MRI of the brain for future reference using the navigation system Brainsight.

After determining the hot spot and resting MT for the right ECU, rTMS was applied at 90% resting MT (Kobayashi et al. 2004) at 1-Hz frequency for a total of 15 min (900 pulses) to either the left M1 or vertex using the air-cooled figure-of-8 coil (70-mm wing diameter). In a 3rd condition, a sham air-cooled figure-of-8 coil (70-mm wing diameter) was used for left M1 stimulation.

Data Analysis

IHI and SICI.

In 1 subject, data were accidentally not saved and subsequently not available for analysis. Data for the remaining 11 subjects were entered into the analysis. MEP amplitudes were measured offline. Recordings with EMG background activity were excluded from further analysis. For IHI and SICI, MEP amplitudes elicited at different ISIs were calculated as a percentage of the mean test MEP amplitude evoked by TS alone. CS intensities were expressed as percentage of MSO.

Motor task.

ACCURACY.

Correct movements were defined as completion of the movement in the allocated time of 2 s with the cursor display in the target area (defined as the area surrounding the midpoint ± 50% of the distance between midpoint and border of the square). The number of correct movements was expressed as percentage of all movements for the target size. For each subject, target size, intervention, and time point (prior or postintervention), the percentage of hits was calculated. For further statistical analysis, the intervention-related changes in the percentage of hits were expressed as ratio between percentage of hits before and postintervention.

MOVEMENT TIME.

Movement time was defined as the time interval between the onset of the target display and time of button push indicating the successful completion of each trial. Only correct movements were considered for analysis. For each subject, target size, intervention, and time point (before or postintervention), the mean movement time was calculated.

Statistical Methods

The within-group factors of intervention (TMS applied to iM1 or vertex or sham stimulation applied to M1), hand [left (L) and right (R)], and target size [small, medium, large, and extra large (x-large)] were analyzed in a repeated-measures ANOVA. Post hoc analysis was performed using two-tailed paired t-test. Linear regression analysis was calculated to test the relationship between rTMS-related changes in left-hand motor performance for the smallest target size and measures of IHI and SICI and performance.

RESULTS

SICI

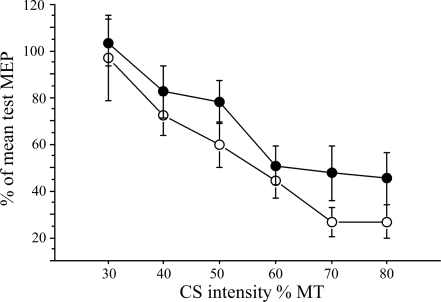

There was a significant effect of the CS on the MEP evoked by the subsequent TS that did not differ between the hemispheres [repeated-measures ANOVA: main effects: CS intensity: F = 15.75, P < 0.0001; hemisphere: not significant (ns), interaction: hemisphere × CS intensity: ns; Fig. 2].

Fig. 2.

Short interval cortical inhibition (SICI): the effect of the conditioning pulse (CS) on the motor evoked potential (MEP) evoked by the test pulse (TS) at an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 2 ms is displayed for right (●) and left (○) M1 stimulation. The effect of the CS on the conditioned MEP is expressed as percentage of the mean test MEP. The intensity of CS differed between 30 and 80% of MT. There was no relationship between SICI at CS intensity of maximum inhibition (80% MT) of the left and right M1 and accuracy of the left-hand motor performance for the smallest target (regression analysis: not significant).

IHI

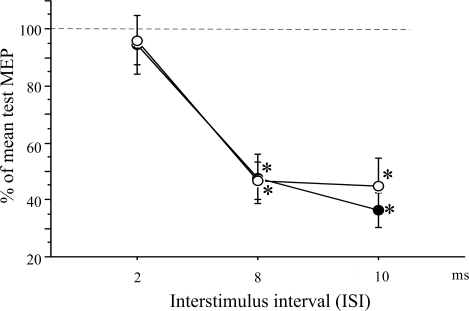

Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time (ISI) on the MEP amplitude evoked by the TS of the corresponding M1 (F = 48.91, P < 0.0001). The effect of side (left vs. right) was not significant (Fig. 3). Post hoc testing with a paired t-test revealed a significant difference between the test MEP amplitude and the conditioned MEP amplitude at ISIs of 8 ms (left: t = 6.11, P = 0.0001; right: t = 8.17, P < 0.0001) and 10 ms (left: t = 10.28, P < 0.0001; right: t = 5.56, P = 0.0002).

Fig. 3.

Interhemispheric inhibition (IHI). At ISIs of 8 and 10 ms, there was a significant inhibitory effect when CS was applied to the left (○) or right (●) M1 on the MEP evoked by the subsequent TS of the corresponding opposite M1. *P < 0.0001. Values are means ± SE.

Behavioral Data

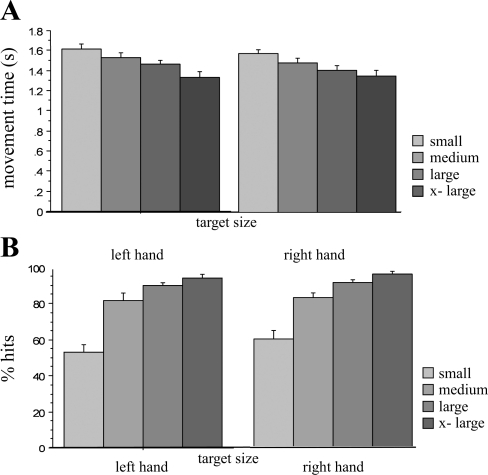

At baseline, the movement time increased linearly with decreasing target size (Fig. 4A; y = 3.529 + 0.167·x; r2 = 0.257, P < 0.0001). Similarly, the number of successful pointing movements (expressed as percentage of hits) decreased linearly as the size of the target decreased (Fig. 4B; linear regression analysis: y = 112.228 − 12.539·x; r2 = 0.578; P < 0.0001). These results confirm that the employed pointing task indeed represents a task with a parametric increase in precision that follows the speed-accuracy trade-off, also known as Fitts' law (Fitts 1954). Further analysis revealed no differences in performance before the different interventions (repeated ANOVA with movement time as dependent variable and different interventions as independent variable: ns) indicating a stable baseline performance and no carry-over effect from previous sessions.

Fig. 4.

Effect of increasing the target size on hand motor performance. Data for baseline performance before iM1 stimulation are shown for both hands. A: movement time increased linearly as the size of the target decreased. B: the number of correct movements (expressed as percentage of hits) decreased linearly as the size of the target decreased [from the largest target (x-large) to the smallest target (small)].

Effect of rTMS Applied to Left M1 on Hand Motor Performance

TMS parameter.

Repetitive TMS was applied at a mean intensity of 56.84 ± 7.31% of MSO, ∼90% of subject's mean MT (63.23 ± 9.40 MSO). Stimulation intensity was kept constant across the different conditions (vertex and sham stimulation).

Accuracy of motor performance (percentage of hits).

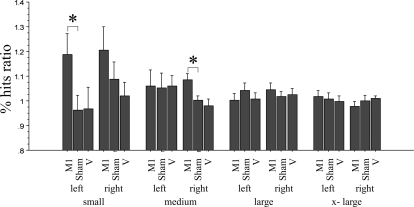

All subjects completed the three different interventions. Repeated-measures ANOVA with intervention (TMS applied to iM1 or vertex or sham stimulation applied to iM1), hand (L and R), and target size (small, medium, large, and x-large) as within-group variables revealed a significant main effect for target size (F = 3.65, P = 0.02) on the dependent variable, which was the percentage of hits ratio. There was a trend for intervention (F = 2.20, P = 0.13), whereas hand had no effect. Interaction between target size and intervention was significant (F = 2.58, P = 0.03). Other interactions were not significant (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of the different interventions on the accuracy of motor performance. Changes in accuracy are expressed as ratio (percentage of hits ratio = percentage of hits postintervention/percentage of hits preintervention). M1 stimulation resulted in a significant improvement in the accuracy of highly skilled level performance (small target) of the left hand and a tendency to improve right-hand performance. This was not seen with sham stimulation (sham) or TMS of the vertex (V). The target size is indicated by the labels small, medium, large, and x-large. left, Left hand; right, right hand. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

For the left hand, post hoc testing revealed that for the large and medium sized targets (medium, large, and x-large in Fig. 5), performance remained similar across time, regardless of intervention (paired t-test, ns). In contrast, for the small target size (Fig. 5), M1 stimulation resulted in a statistically significant improvement in accuracy for the left hand (before: 52.98 ± 16.21%, after: 59.99 ± 15.64%; t-test: t = −2.37, P = 0.038).

For the right hand, there was a tendency for improved accuracy for the small target (before: 59.48 ± 16.16%, after: 67.85 ± 12.36%; t-test: ns). This improvement reached statistical significance for the medium-sized target (before: 82.89 ± 9.94%, after: 89.22 ± 6.38%; t-test: t = −3.29, P = 0.007). There was no effect on the two larger-sized targets (large and x-large in Fig. 5; t-test: ns).

Speed of motor performance.

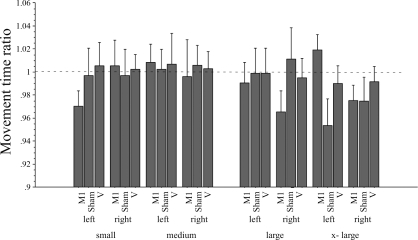

At times, subjects failed to indicate a completed movement by pushing the button located on the top of the joystick. A minimum of 5 trials per target size was required to be entered into group analysis. In 2 subjects, the movement times of 1 experimental condition (rTMS of vertex in 1 subject and rTMS of M1 in the 2nd subject) were completely missing due to the subject's failure to indicate the completion of the movement. Their information did not enter further analysis. Consequently, data pertaining to the movement time are less robust. As indicated in Fig. 6, there was a tendency toward decreased movement times following the rTMS of M1. However, repeated-measures ANOVA with intervention (TMS applied to M1 or vertex or sham stimulation applied to M1), hand (L and R), and target size (small, medium, large, and x-large) as within-group variable revealed no significant main effects or interactions of the different variables. Post hoc testing with paired t-test revealed no significant differences between the different interventions.

Fig. 6.

Effect of the different interventions on the movement time. Changes in movement time are expressed as a ratio (movement time postintervention/movement time preintervention). M1 stimulation resulted in a shortened movement time for the target requiring more precision (small target) of the left hand. This did not reach significance in the right hand or with sham stimulation or TMS of the vertex. The target size is indicated by the labels small, medium, large, and x-large. Values are means ± SE.

Exploring the Effect of M1 Priming in a Post Hoc Analysis

In the present study, left M1 stimulation resulted in improved accuracy of performance for both the left and right hands on the small and/or medium targets (Fig. 5). A left M1 stimulation-related enhancing effect on motor performance of both hands has not been reported before. This effect was specific for the location and the intervention, as rTMS applied to the vertex and sham stimulation to M1 did not reveal any effect on performance. In a post hoc analysis, we explored the possibility that the improved performance of the right hand was due to a rTMS-related priming of left motor cortex with subsequent motor learning during the execution of the pointing task (Iyer et al. 2003; Siebner et al. 2004). Measurements of accuracy were obtained in 3 blocks of 28 trials (with 7 trials for each target size; see materials and methods). We would argue that if M1 stimulation resulted in priming of the stimulated motor cortex and subsequent motor learning of the pointing task during the measurements, one would expect an increasingly improved performance over the three blocks with the best performance in the last block and the least accurate performance in the first block. A regression analysis revealed no linear increase of performance with left or right hand over the three blocks when measured for the small and medium target sizes.

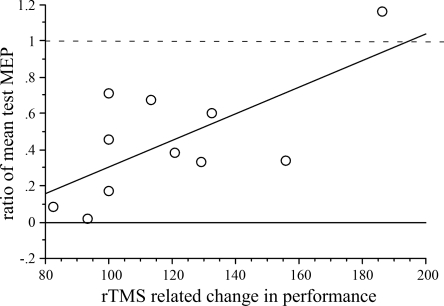

Relationship Between rTMS-Related Effects on Left-Hand Performance and Baseline SICI and IHI

As level of intracortical excitability (specifically, SICI) (Daskalakis et al. 2006) and IHI (Gilio et al. 2003) are implicated to predict or mediate rTMS-related effects on stimulated M1 and nonstimulated M1, we also explored the relationship between the IHI from the stimulated to the nonstimulated M1 (left on right M1 at the ISIs of 8 and 10 ms) and rTMS-related improvement in the accuracy of hand motor performance. For the left hand, there was a significant correlation between rTMS-related increases in accuracy of performance on the small targets and magnitude of IHI at ISI of 10 ms, with greater increases in accuracy seen in subjects with less IHI from the stimulated to the nonstimulated M1 (r2 = 0.47, F = 7.81, P = 0.02; Fig. 7). This was not seen for the ISI of 8 ms. For the right hand, there was no correlation between IHI at 8 or 10 ms and rTMS-related increases in the accuracy of performance on the small or medium targets. There was no relationship between baseline SICI and improved performance of either side.

Fig. 7.

Relationship between IHI of left to right M1 and left-hand performance. IHI at ISI of 10 ms is plotted against rTMS-related improvement of left-hand performance on the smallest target. Performance is expressed as percentage of improvement over baseline following rTMS of left M1.

DISCUSSION

The two main findings of the present study were, first, that the rTMS-related effects on accuracy of motor performance were dependent on the level of precision required for the completion of the motor task and, second, that rTMS applied to the left M1 improves accuracy in motor performance of both hands.

As demonstrated by the increasing movement time and decreasing accuracy as a function of target size, the employed pointing task was effective in shifting motor performance level along a continuum as a function of target size (Fig. 4). It was therefore a valid motor task to determine whether the effect of low-frequency rTMS of left M1 on motor performance of the hand was dependent on the level of task difficulty as indicated by the target size. We found that low-frequency rTMS of left M1 improved accuracy and speed for smaller targets, whereas performance on the larger targets remained unaffected. This effect was specific for rTMS of left M1, as it was not seen with vertex stimulation or sham stimulation of left M1. This suggests that the effect of rTMS on hand motor performance is a function of task difficulty, in this case as indicated by the increasing demand for precision. As indicated by the tendency of rTMS-related shortening of movement times in Fig. 6, the improved precision did not occur at the expense of time (accuracy speed trade-off).

This effect cannot be explained by carry-over effects, as the order of experiments was randomized, and analysis of the baseline performance (performance before the different interventions) revealed similar results across conditions. However, the accuracy of pointing to the largest target was close to 100% and raises the question of whether the lack of rTMS-related improvement was related to a ceiling effect. This possibility cannot be completely excluded for the performance of the right hand. However, there was no rTMS-related improvement in the medium- and large-sized targets for the left hand, where accuracy was at about 80 and 90%. This would support the specificity of rTMS-related effects for motor performance with high demands on precision. Similar to the rTMS-related effects on accuracy, the rTMS-related improvement in speed was restricted to the smaller target sizes, further supporting the results of a task difficulty-related effect of rTMS.

A bilateral effect of left M1 subthreshold low-frequency rTMS on hand motor performance was unexpected, as it has not been reported before. In previous studies, rTMS-related improvement of movement execution time for a sequential key-pressing and finger-tapping task were restricted to the hand ipsilateral to the stimulated M1 (Dafotakis et al. 2008; Kobayashi et al. 2004). As rTMS protocols differed in respect to the intensity [100% MT in the study by Dafotakis et al. (2008)] and number of applied stimuli [600 stimuli in the studies by Dafotakis et al. (2008) and Kobayashi et al. (2004)], the lack of a bilateral effect in these previous studies could be explained by the differences in the rTMS protocols. Furthermore, because of age-related effect on brain activity during performance of motor tasks (Mattay et al. 2002; Ward and Frackowiak 2003), the considerable older age of our subjects compared with the subjects in these previous studies (mean ages 27 ± 6 and 29.6 ± 3.6 yr, respectively) could account for the differences in the findings.

One may argue that the measurement of the pointing task may represent motor practice and could therefore result in changes in the homeostasis of motor cortices, an effect referred to as priming of M1. Practicing a motor task leads to increases in M1 excitability (Butefisch et al. 2000). If indeed the execution of the pointing task induced increased M1 excitability, the suppressive effect of low-frequency rTMS on M1 excitability may have been augmented (Iyer et al. 2003; Siebner et al. 2004). This was not tested in the present study. However, an increase in the nonstimulated cM1 excitability was demonstrated using 1-Hz rTMS at an intensity of 90% MT (Kobayashi et al. 2004). These measurements were obtained after motor practice of button presses (15-min training of 760 warm-up trials before the experiment and 5 min of 240 trials in each hand before rTMS). This exposure to motor training is comparable with our paradigm. Furthermore, we did not find any rTMS-related learning effect during the execution of the pointing task in our post hoc analysis. This would argue against a priming effect of rTMS on motor cortex and related improved performance.

Considering the low intensity of rTMS and the small figure-of-eight coil, the cortical area activated by rTMS is relatively focal. Although we did not measure the effect of rTMS on M1 excitability in the present study, decreased excitability of the stimulated M1 was demonstrated previously by several investigators using a similar protocol (Maeda et al. 2000a,b; Sommer et al. 2002). This effect seems to be more prominent with higher intensities (Chen et al. 1997). Furthermore, Di Lazzaro et al. (2008) demonstrated an association between reduced amplitude of MEPs and suppressed amplitudes of later I-waves, thereby confirming the cortical origin of 1-Hz rTMS-related effects on MEPs. However, as rTMS-related effects on M1 are not consistently reported in the literature (Fitzgerald et al. 2006), we cannot comment on the effects on M1 excitability in the present study.

Furthermore, TMS applied to one area of the brain can also modulate neural circuits in nearby or remote, connected brain regions, both within and between the two hemispheres. Specifically, reducing the excitability of one motor cortex has an effect on the motor cortex of the other hemisphere. There is substantial evidence that each M1 exerts reciprocal influences on homonymous motor representations in the opposite M1 via the corpus callosum (Butefisch et al. 2008; Daskalakis et al. 2002; Di Lazzaro et al. 1999; Ferbert et al. 1992; Meyer et al. 1995; Murase et al. 2004).

The effects of M1 stimulation on excitability of the nonstimulated M1 have been inconsistent, as summarized in a recent review by Daskalakis et al. (2006). For example, suprathreshold 1-Hz stimulation (900 stimuli) of left M1 resulted in an increase of MEP amplitude in the nonstimulated right M1 (Gilio et al. 2003; Schambra et al. 2003), whereas measures of SICI and intracortical facilitation remained unaffected (Gilio et al. 2003). Conversely, rTMS of left M1 at intensities at resting MT resulted in a decrease of MEP amplitudes (Wassermann et al. 1998). It was suggested that these different findings in rTMS-related effects might be due to differences in the intensities of the rTMS (Gilio et al. 2003). Whereas intensities in the studies by Gilio et al. (2003) and Schambra et al. (2003) were set at about 115–120% of MT, sufficient to activate interhemispheric inhibitory effects, Wassermann et al. (1998) used intensities at resting MT. However, this notion is not supported by more recent reports of increases in MEP amplitudes with subthreshold rTMS at 1 Hz (Kobayashi et al. 2004) and decreases in MEP amplitudes with suprathreshold stimulation (Plewnia et al. 2003).

Factors that may contribute to these conflicting results are differences in the baseline neurophysiological characteristics of subjects. Relationships between the effect of rTMS and baseline neurophysiological characteristics of subjects, e.g., measures of SICI, were previously reported (Bagnato et al. 2005; Daskalakis et al. 2006). In the present study, a relationship between baseline SICI and rTMS-related improvement was not found, whereas baseline IHI from the left M1 to right M1 was related to the effect of rTMS on M1 on left-hand motor performance. Specifically, in subjects with low-level IHI, rTMS of left M1 resulted in a greater improvement in accuracy in the pointing task compared with subjects with a high level of IHI. However, in further experiments, these findings need to be confirmed, and the direct effect of rTMS on IHI and SICI needs to be tested.

In the present study, it is likely that both local and remote effects of TMS contributed to the TMS-induced behavioral changes. The finding of a bilateral effect of left M1 rTMS could be explained by modulation of M1 circuitry that exerts effects ipsilaterally but also projects to the motor cortex of the other hemisphere. It is well-known that input of multiple areas including posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and dorsal prefrontal cortex project to iM1 and that these areas also connect either directly or indirectly to cM1. It was demonstrated that PPC connects either directly or indirectly to cM1. One proposed indirect connection between PPC and cM1 involves the projection to iM1 and via corpus callosum to the homologous area of cM1 (Koch et al. 2009). Modulating the excitability of one M1 could therefore affect the cM1 in various aspects that could carry behavioral implications. Specifically, in the present study, improved accuracy in the pointing task requiring high precision could be explained by improved processing or integrating of PPC input to iM1 with subsequent projection to cM1. The data are consistent with the notion of left hemispheric dominance in motor programming and are similar to the results from an earlier study by Terao and colleagues (2005). In their choice reaction time task, TMS applied to left M1 produced bilateral effects for hand performance, whereas TMS applied to right M1 produced effects for the right hand only. Additional experiments with rTMS applied to the right M1 would further support this notion.

In conclusion, we found subthreshold rTMS of left M1-related behavioral effects that were dependent on the level of precision required for the completion of the motor task and evident in an improved accuracy in motor performance of both hands. The finding is consistent with reports of left hemispheric dominance in motor programming where left M1 disruption produces bilateral behavioral effects. Alternatively, interhemispheric projections of nonprimary motor areas via left M1 may account for some of the bilateral effects on accuracy of performance. The results would also support the notion that M1 functions at a higher level in motor control by integrating afferent input from nonprimary motor area and then generating a descending motor command that defines the kinematics of the movement (for review, see Kalaska 2009). Further experiments are needed to verify left hemispheric dominance in motor programming and to define further the rTMS-related effects on M1 excitability of both hemispheres and IHI.

GRANTS

This research was supported by a West Virginia University Research Development Grant and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01-NS-060830.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our subjects for their participation in the study. We thank Drs. Robert Chen and Leonardo Cohen for critical discussion of the results and Dr. Sebastian Buetefisch for technical support.

REFERENCES

- Bagnato S, Currà A, Modugno N, Gilio F, Quartarone A, Rizzo V, Girlanda P, Inghilleri M, Berardelli A. One-hertz subthreshold rTMS increases the threshold for evoking inhibition in the human motor cortex. Exp Brain Res 160: 368–374, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butefisch CM, Davis BC, Wise SP, Sawaki L, Kopylev L, Classen J, Cohen LG. Mechanisms of use-dependent plasticity in the human motor cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 3661–3665, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butefisch CM, Kleiser R, Korber B, Muller K, Wittsack HJ, Homberg V, Seitz RJ. Recruitment of contralesional motor cortex in stroke patients with recovery of hand function. Neurology 64: 1067–1069, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butefisch CM, Netz J, Wessling M, Seitz RJ, Homberg V. Remote changes in cortical excitability after stroke. Brain 126: 470–481, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butefisch CM, Wessling M, Netz J, Seitz RJ, Homberg V. Relationship between interhemispheric inhibition and motor cortex excitability in subacute stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 22: 4–21, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan MJ, Honda M, Weeks RA, Cohen LG, Hallett M. The functional neuroanatomy of simple and complex sequential finger movements: a PET study. Brain 121: 253–264, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Classen J, Gerloff C, Celnik P, Wassermann EM, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Depression of motor cortex excitability by low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology 48: 1398–1403, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Tam A, Butefisch C, Corwell B, Ziemann U, Rothwell JC, Cohen LG. Intracortical inhibition and facilitation in different representations of the human motor cortex. J Neurophysiol 80: 2870–2881, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafotakis M, Grefkes C, Wang L, Fink GR, Nowak DA. The effects of 1 Hz rTMS over the hand area of M1 on movement kinematics of the ipsilateral hand. J Neural Transm 115: 1269–1274, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis ZJ, Christensen BK, Fitzgerald PB, Roshan L, Chen R. The mechanisms of interhemispheric inhibition in the human motor cortex. J Physiol 543: 317–326, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis ZJ, Moller B, Christensen BK, Fitzgerald PB, Gunraj C, Chen R. The effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cortical inhibition in healthy human subjects. Exp Brain Res 174: 403–412, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Oliviero A, Profice P, Insola A, Mazzone P, Tonali P, Rothwell JC. Direct demonstration of interhemispheric inhibition of the human motor cortex produced by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Exp Brain Res 124: 520–524, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Pilato F, Dileone M, Profice P, Oliviero A, Mazzone P, Insola A, Ranieri F, Tonali PA, Rothwell JC. Low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation suppresses specific excitatory circuits in the human motor cortex. J Physiol 586: 4481–4487, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbert A, Priori A, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Colebatch JG, Marsden CD. Interhemispheric inhibition of the human motor cortex. J Physiol 453: 525–546, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts PM. The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. J Exp Psychol 47: 381–391, 1954 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PB, Fountain S, Daskalakis ZJ. A comprehensive review of the effects of rTMS on motor cortical excitability and inhibition. Clin Neurophysiol 117: 2584–2596, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilio F, Rizzo V, Siebner HR, Rothwell JC. Effects on the right motor hand-area excitability produced by low-frequency rTMS over human contralateral homologous cortex. J Physiol 551: 563–573, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel FC, Celnik P, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F, Byblow WD, Buetefisch CM, Rothwell J, Cohen LG, Gerloff C. Controversy: noninvasive and invasive cortical stimulation show efficacy in treating stroke patients. Brain Stimul 1: 370–382, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel F, Kirsammer R, Gerloff C. Ipsilateral cortical activation during finger sequences of increasing complexity: representation of movement difficulty or memory load? Clin Neurophysiol 114: 605–613, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer MB, Schleper N, Wassermann EM. Priming stimulation enhances the depressant effect of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neurosci 23: 10867–10872, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaska JF. From intention to action: motor cortex and the control of reaching movements. Adv Exp Med Biol 629: 139–178, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Hutchinson S, Schlaug G, Pascual-Leone A. Ipsilateral motor cortex activation on functional magnetic resonance imaging during unilateral hand movements is related to interhemispheric interactions. Neuroimage 20: 2259–2270, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Hutchinson S, Theoret H, Schlaug G, Pascual-Leone A. Repetitive TMS of the motor cortex improves ipsilateral sequential simple finger movements. Neurology 62: 91–98, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G, Fernandez Del Olmo M, Cheeran B, Schippling S, Caltagirone C, Driver J, Rothwell JC. Functional interplay between posterior parietal and ipsilateral motor cortex revealed by twin-coil transcranial magnetic stimulation during reach planning toward contralateral space. J Neurosci 28: 5944–5953, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G, Ruge D, Cheeran B, Fernandez Del Olmo M, Pecchioli C, Marconi B, Versace V, Lo Gerfo E, Torriero S, Oliveri M, Caltagirone C, Rothwell JC. TMS activation of interhemispheric pathways between the posterior parietal cortex and the contralateral motor cortex. J Physiol 587: 4281–4292, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze M, Markert J, Sauseng P, Hoppe J, Plewnia C, Gerloff C. The role of multiple contralesional motor areas for complex hand movements after internal capsular lesion. J Neurosci 26: 6096–6102, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda F, Keenan JP, Tormos JM, Topka H, Pascual-Leone A. Interindividual variability of the modulatory effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cortical excitability. Exp Brain Res 133: 425–430, 2000a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda F, Keenan JP, Tormos JM, Topka H, Pascual-Leone A. Modulation of corticospinal excitability by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 111: 800–805, 2000b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattay VS, Fera F, Tessitore A, Hariri AR, Das S, Callicott JH, Weinberger DR. Neurophysiological correlates of age-related changes in human motor function. Neurology 58: 630–635, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BU, Roricht S, Grafin von Einsiedel H, Kruggel F, Weindl A. Inhibitory and excitatory interhemispheric transfers between motor cortical areas in normal humans and patients with abnormalities of the corpus callosum. Brain 118: 429–440, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase N, Duque J, Mazzocchio R, Cohen LG. Influence of interhemispheric interactions on motor function in chronic stroke. Ann Neurol 55: 400–409, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9: 97–113, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plewnia C, Lotze M, Gerloff C. Disinhibition of the contralateral motor cortex by low-frequency rTMS. Neuroreport 14: 609–612, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossini PM, Barker AT, Berardelli A, Caramia MD, Caruso G, Cracco RQ, Dimitrijević MR, Hallett M, Katayama Y, Lücking CH, Maertens de Noordhout A, Marsden CD, Murray NM, Rothwell J, Swash M, Tomberg C. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application. Report of an IFCN committee. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 91: 79–92, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer M, Biesecker JC, Schulze-Bonhage A, Ferbert A. Transcranial magnetic double stimulation: influence of the intensity of the conditioning stimulus. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 105: 462–469, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schambra HM, Sawaki L, Cohen LG. Modulation of excitability of human motor cortex (M1) by 1 Hz transcranial magnetic stimulation of the contralateral M1. Clin Neurophysiol 114: 130–133, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler RD, Noll DC, Thiers G. Feedforward and feedback processes in motor control. Neuroimage 22: 1775–1783, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebner HR, Lang N, Rizzo V, Nitsche MA, Paulus W, Lemon RN, Rothwell JC. Preconditioning of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation with transcranial direct current stimulation: evidence for homeostatic plasticity in the human motor cortex. J Neurosci 24: 3379–3385, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M, Lang N, Tergau F, Paulus W. Neuronal tissue polarization induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation? Neuroreport 13: 809–811, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strens LH, Oliviero A, Bloem BR, Gerschlager W, Rothwell JC, Brown P. The effects of subthreshold 1 Hz repetitive TMS on cortico-cortical and interhemispheric coherence. Clin Neurophysiol 113: 1279–1285, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terao Y, Furubayashi T, Okabe S, Arai N, Mochizuki H, Kobayashi S, Yumoto M, Nishikawa M, Iwata NK, Ugawa Y. Interhemispheric transmission of visuomotor information for motor implementation. Cereb Cortex 15: 1025–1036, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstynen T, Diedrichsen J, Albert N, Aparicio P, Ivry RB. Ipsilateral motor cortex activity during unimanual hand movements relates to task complexity. J Neurophysiol 93: 1209–1222, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward NS, Frackowiak RS. Age-related changes in the neural correlates of motor performance. Brain 126: 873–888, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassermann EM, Wedegaertner FR, Ziemann U, George MS, Chen R. Crossed reduction of human motor cortex excitability by 1-Hz transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurosci Lett 250: 141–144, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstein CJ, Grafton ST, Pohl PS. Motor task difficulty and brain activity: investigation of goal-directed reciprocal aiming using positron emission tomography. J Neurophysiol 77: 1581–1594, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]