Abstract

PURPOSE

To describe the differential completion rates and cost of sequential methods for a survey of adolescent regional healthcare delivery organization enrollees.

METHODS

4000 randomly selected enrollees were invited to complete a mailed health survey. Techniques used to boost response included: 1) a follow-up mailing 2) varying the appearance of the survey 3) reminder calls 4) phone calls to obtain parent and child consent and administer the survey. We evaluated the outcome and costs of these methods.

RESULTS

783 (20%) enrollees completed the 1st mailed survey, and 521 completed the 2nd, increasing the overall response rate to 33%. Completion was significantly higher for respondents who received only the plain survey than those receiving only the color (p<.001). Reminder calls boosted response by 8%. Switching to phone survey administration boosted response by 20% to 61%. The cost per completed survey was $29 for the first mailing, $26 after both mailings, $42 for mailings and reminder calls, and $48 for adding phone surveys.

CONCLUSIONS

The response to mailings and reminder calls was low and the cost high, with decreasing yield at each step, though some low cost techniques helpful. Results suggest phone surveys may be most effective among similar samples of adolescents.

INTRODUCTION

Response rates in population-based surveys have been declining for several decades, and achieving a response rate high enough for results to be considered valid is challenging given real-world budget constraints (1). Surveying adolescents is especially difficult, given the added logistical challenges and expense of obtaining informed parental consent prior to contacting the adolescent. However, overcoming the challenge of non-response is vital for accurately monitoring the health of this population, as adolescence is a crucial time for health providers and parents to help teenagers establish good health behaviors to prevent future adulthood morbidity and mortality (2).

Healthcare delivery organizations, such as HMOs and insurance providers, have a clear stake in learning more about how to teach adolescents to establish good health behaviors, because success means healthier enrollees and potential cost savings by reducing the number of enrollees who develop chronic conditions that may have been prevented. To do this, healthcare organizations must have the ability to systematically collect data and disseminate findings to be incorporated into the clinical practice of their providers. However, implementing effective survey methodology is difficult and costly. Often postal and electronic questionnaires are the only financially viable option for collecting data from large geographically dispersed populations, but low response rates undermine the validity of the results (3). Telephone interviewing technology has advanced survey research, but increased cell phone and caller ID usage in recent years has made reaching families more difficult, resulting in telephone surveys becoming increasingly more expensive (4).

To date, school-based surveys are the main method health researchers use to measure the health of the U.S. adolescent population (5-7). Data from national school based surveys are routinely used by federal, state and local agencies and nongovernmental organizations to support school health curricula, new legislation, and funding for new health promotion initiatives (2). School-based surveys offer particular advantages—as classrooms offer a “captive” population of adolescents and parents may not be required to give consent prior to the survey (i.e. only passive consent or the ability to opt out may be required depending on school policy) (8). While the importance of these school-based health behavior surveys cannot be underestimated, there are important barriers to obtaining responses to recognize. Most importantly, school-based surveys only apply to youth who attend school, but youth who are either not attending school or are frequently absent may be more likely to engage in high-risk behavior (9, 10). Several large national surveys systematically exclude schools with low response rates, which also leads to underestimates of certain high-risk behaviors (11).

Healthcare delivery organizations are in a unique position to overcome some of the caveats of school-based survey methodology—with access to adolescent enrollees not attending public schools, and contact information (such as cell phone numbers) not publicly available. Also, since parental consent is usually required by law for survey researchers operating outside schools, health care delivery organizations may be in a better position to obtain this consent. Parents are more likely to consent to their child to participating in a survey conducted by an organization they trust than by an entity unknown to them (12).

Despite these potential advantages, survey methodology used by healthcare organizations to capture information about their adolescent populations has rarely been described in the literature. There is an absence of published research findings on surveys conducted among large community based samples of adolescents outside the school setting. The purpose of this paper is to fill a gap in the publicly available literature and describe the differential completion rates and associated costs with sequential mail and telephone methods used to survey adolescents enrolled in a regional healthcare delivery organization in the Pacific Northwest.

METHODS

Study Participants

Group Health is a nonprofit health care system, that provides comprehensive health care to over 600,000 residents of Washington State and Northern Idaho (13). Research study participants were recruited by staff at the Group Health Research Institute for the AdolSCent Health [ASC] Study. As previously described, the purpose of ASC was to examine the clinical and demographic predictors of depression persistence in adolescents and the sample size was chosen to evaluate the performance of a two stage depression screening procedure (14). In stage 1, Group Health staff invited 4000 randomly selected English-speaking enrollees, age 13-17, who had seen a Group Health provider at least 1 time in the last year to participate in a brief survey between September 2007 and June 2008. In stage 2, a subset of youth participating in stage 1, were invited to participate in a follow-up phone interview study, during which more in-depth information was obtained on depressive symptoms, functional impairment, and health behaviors. The focus of this analysis is on Stage 1 methods described below.

The parents/guardians of all selected enrollees were mailed two copies of a consent form, a survey for their child, and an invitation letter appealing parents to participate and ask their child to participate in a survey about “teen health” to help understand “the needs of our teen patients.” If parents agreed to their child's participation, they were instructed to sign one copy of the consent form and give their consent form and study survey to their child to complete in a private place. The child received a $2 pre-incentive with the first mailed survey and a postage paid envelope for completing the survey and mailing back to Group Health with a copy of the consent form signed by their parent/guardian. Completion of the survey was taken as a form of assent by the child and a phone number for questions was included on all study materials. Additional attempts were made by mail and phone to obtain consent from a parent/guardian for surveys returned without consent forms. All study procedures were approved by the Group Health institutional review board. Participants and their parents/guardians were required to provide either written or verbal consent for participation.

Survey Instrument

The ASC survey consisted of 10 items about age, gender, weight, height, sedentary behaviors, functional impairment and depressive symptoms. Activity related items included questions about the hours and minutes spent on a computer, watching TV, and “exercising or participating in an activity that makes you sweat & breathe hard.” Functional impairment was assessed using 3 items from the Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS) (15), a psychosocial functional impairment scale widely used in youth anxiety and depression studies. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item Depression Scale (PHQ-2) (16), which at the time of this study had not yet been validated to screen adolescent populations for depression. A small pilot study (N=100) was conducted a few months prior to study launch to inform survey design (i.e. layout and formatting decisions).

Procedures Used to Boost Response Rate

Additional attempts were made by mail and phone to boost the initial response rate to the mailed survey. First, non-responders received a second survey approximately 2 weeks later. Next, a portion of non-responders received a reminder call (defined as actual phone contact with a parent or guardian) to complete the survey, and an additional mailed survey was sent upon request.

Two variations of the appearance of the survey were used in these mailings—a color tri-fold and a plain black and white single sheet. The first portion of participants received a color tri-fold version of the survey, but response was lower than expected based on results from the pilot study, so methods were changed to implement the version used in the pilot study—a black & white single sheet survey.

Last, study methods were changed to obtain consent and survey responses via phone from the remaining youth who had not yet received a reminder call, and a portion of youth whose parents stated intent to participate during reminder calls but did not. Interviewers were required to obtain verbal consent from the parents/guardians and assent from the youth before administering the phone survey to the youth. Telephone interviewers used computer-assisted telephone interviewing [CATI] software and were required to record the outcome of all contact attempts.

Analysis of Differential Survey Completion and Cost

Available demographic variables for the survey refusers and non-responders included age and sex. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association between age, sex, timing of the survey invitation and survey completion rate (the independent variables were identified a priori). Age was analyzed as a categorical and continuous variable (data not shown). Adjusted analyses for mail survey completion include the independent variables of interest, as well as type of survey sent and whether or not a reminder call was attempted. Both adjusted and unadjusted analyses are presented.

Since all participants were initially invited to participate by mail, the cost of phone surveying versus mail surveying could not be directly compared. Cost figures include all materials used in the mailings (ie. letterhead, envelopes, reply envelopes, questionnaires); postage (outgoing and incoming); $2 incentive for the first mailing; and personnel--including mailing processing time, data entry time for surveys returned by mail, time for programming the CATI instrument for administering the telephone interviews, and interviewer hours for reminder calls and phone survey administration. Cost estimates do not include leased space costs for the survey personnel or any administrative costs associated with conducting a research study, such as IRB review. Cost of survey administration is presented by calculating how the cost per completed survey changed by adding each incremental survey method (2nd mailing, reminder calls, and survey calls).

RESULTS

Survey Response

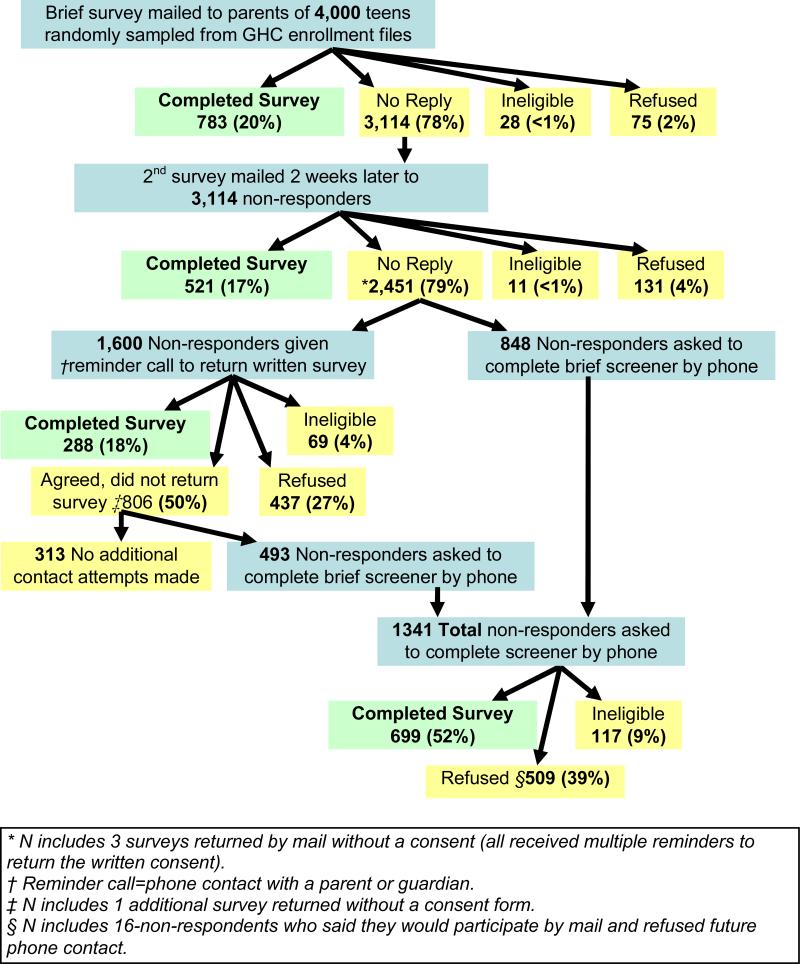

Of 4000 Group Health teens mailed the first survey, 3114 (78%) did not reply, 783 (20%) completed the survey, 75 (2%) actively refused study participation (by mail or phone), and 28 (<1%) were ineligible (no longer a Group Health enrollee, cognitively or physically not able to participate, or survey was undeliverable) (Figure1). Of the 3114 mailed the 2nd survey, 2451 (79%) did not reply, 521 (17%) completed the survey, 131 (4%) refused and 11 (<1%) were ineligible. Less than <1% of completed surveys were returned without the consent form and additional mail and phone attempts to obtain consent were successful in all but 4 cases when a parent or guardian could not be reached (see Figure 1 footnote).

Figure1.

Response Rate by Contact Method

When survey formatting was varied among participants 28% received a color tri-fold for both mailings, 35% received the tri-fold followed by a plain black & white single sheet, and 38% received the plain black and white for both mailings. The completion rate was significantly higher for respondents who received only the plain black & white survey compared to those who received the color tri-fold for both mailings (p <.001) (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcome of Varied Survey Appearance

| Total Invited | Completed Survey | Did Not Complete Survey | OR | 95% CI | p-value | *A-OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trifold | 1087 | 313 (29%) | 774 (71%) | 1.0 | 1.00 | ||||

| Trifold & Plain | 1385 | 428 (31%) | 957 (69%) | 1.11 | [.93, 1.32] | .256 | 1.11 | [0.93, 1.32] | .244 |

| Plain | 1498 | 563 (38%) | 926 (62%) | 1.50 | [1.27, 1.78] | <.001 | 1.51 | [1.28, 1.79] | <.001 |

Odds Ratio for survey completion versus refusal or non-response, adjusted for sex and age.

Of the 1,600 participants (65% of the 2451 remaining non-responders) given a reminder telephone call to return the written survey 1,094 (68%) agreed to return the survey, but only 288 (18%) actually returned the completed survey. After survey methods were changed, of the 1341 non-responders who were asked to complete the survey by phone 699 (52%) agreed and 509 (32%) refused.

Correlates of Mail Versus Phone Survey Completion

After adjusting for confounding, there were no significant differences in age, timing of initial contact (Sept, Oct or Nov) or sex for youth who completed the mail survey as compared to those who either refused or did not respond (see Table 2). In contrast, youth who completed the phone survey were significantly older (p=.048) and more likely to complete the survey when contacted in April versus January (p=.009) than those who either refused or did not respond (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Correlates of Mail Survey Completion

| *Total Invited N=3892 | Completed Survey N=1592 (40%) | Did Not Complete Survey N=2300 (60%) | OR | 95% CI | p-value | †A-OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | 1852 | 783 (42%) | 1069 (58%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Boys | 2040 | 809 (40%) | 1231 (60%) | 0.90 | [.79, 1.02] | 0.097 | .95 | [0.82, 1.10] | 0.478 |

| Age 13-14 | 1579 | 665 (42%) | 914 (58%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Age 15-17 | 2313 | 927 (40%) | 1386 (60%) | 0.92 | [.71, 1.05] | 0.204 | 0.93 | [0.80, 1.09] | 0.370 |

| Sept | 1541 | 645 (42%) | 896 (58%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Oct | 1854 | 782 (42%) | 1072 (58%) | 1.01 | [.88, 1.16] | 0.849 | 1.10 | [.82, 1.48] | 0.53 |

| Nov | 497 | 165 (33%) | 332 (67%) | 0.69 | [0.56, 0.85] | 0.001 | .082 | [0.56, 1.19] | 0.29 |

Total invited not including ineligible

OR Adjusted for respective covariates, including sex, age, initial mail month, the type of survey sent and whether or not reminder call attempted.

Table 3.

Correlates of Phone Survey Completion

| *Total Invited N=3892 | Completed Survey N=1592 (40%) | Did Not Complete Survey N=2300 (60%) | OR | 95% CI | p-value | †A-OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | 592 | 350 (59%) | 242 (41%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Boys | 632 | 349 (55%) | 283 (45%) | 0.85 | [.68, 1.07] | 0.17 | .84 | [.67, 1.06] | 0.148 |

| Age 13-14 | 503 | 271 (54%) | 232 (46%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Age 15-17 | 721 | 428 (59%) | 293 (41%) | 1.25 | [0.99, 1.57] | 1.26 | [1.00, 1.59] | 0.048 | |

| January | 769 | 417 (54%) | 352 (46%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| April | 455 | 282 (62%) | 173 (38%) | 1.38 | [1.09, 1.74] | 0.008 | 1.37 | [1.08, 1.74] | 0.009 |

Total invited not including ineligible

OR Adjusted for respective covariates, including sex, age, initial phone attempt month.

Among the parents or guardians who received a reminder call to ask their child to complete the survey, there were no differences in the child's age or sex among those who returned and completed survey and those who said they would but did not (data not shown).

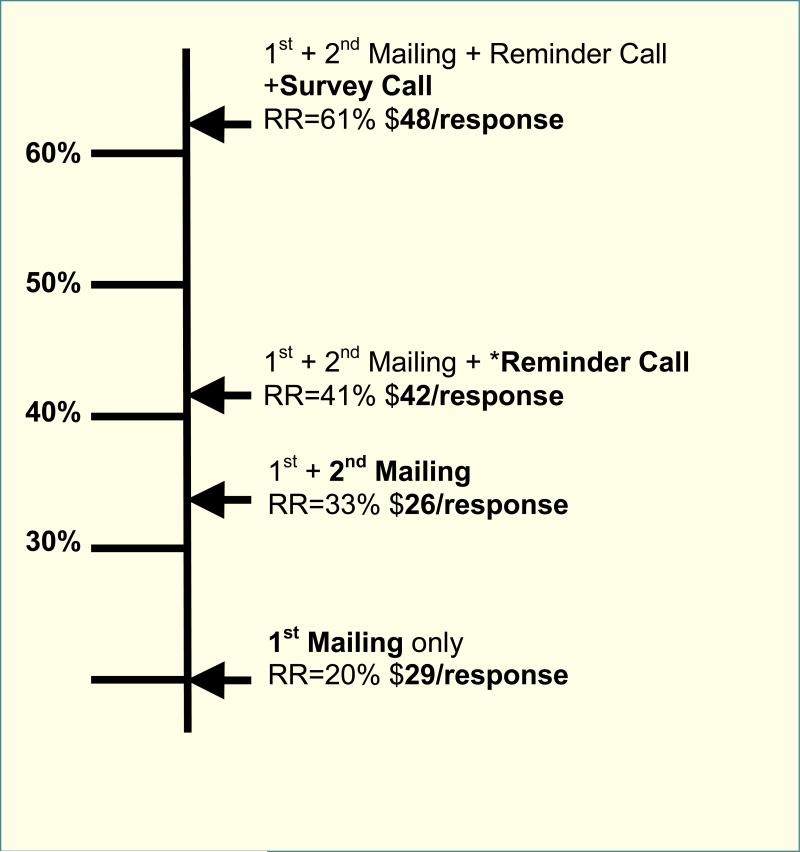

Cost Per Completed Survey

Cost of the initial mailing resulting in a 20% response rate was $29 per response, and adding the follow-up mailing to non-responders decreased the overall cost per response to $26 dollars. Adding the reminder calls resulted in an 8% response rate increase, but at a higher price of $42 per response. Altering recruitment methods to complete the survey by phone increased the cost to $48 per response and resulted in boosting the overall response rate to 61%.

DISCUSSION

Multiple survey methods were used with varying success to achieve a 61% response rate from adolescents enrolled in a regional healthcare delivery organization. The initial mailing resulted in only a 20% response rate at the price of $29/response. Subsequent mailings and reminder calls resulted in a modest response rate increase, but the most success came after survey methods were substantially changed to conduct the consent process and survey with remaining non-responders by phone.

The results of this study suggest some low cost techniques may be useful for boosting survey response rate. Though the follow-up mailing resulted in a modest additional response rate (increasing the total response to 31%), this increase was enough to lower the overall cost of survey administration to $26/response. Varying the appearance of the survey was another relatively successful low cost technique, as the plain black & white single sheet of paper was more successful than the color tri-fold initially mailed to adolescents. To date, few experimental studies of the effect of colored questionnaires have been published, and a recent meta-analysis shows results of these studies have been mixed (17). In this study, color and survey format were altered at the same time so cannot be examined separately, but the plain formatting was significantly more successful. The reason for this is unknown, but it is possible the plain formatting made survey more apparent while the tri-fold may have been mistaken for a brochure and discarded. The same cover letter was included with both versions of the survey and included a broad appeal for parents to ask their children to participate in a study to help understand “the health needs of our teen patient” and it is possible that a different appeal may have increased response. However, our appeal was designed to be consistent with a previous finding that letters clearly indicating the purpose of the survey is to serve the interest of a valued group increase survey participation (18).

The reminder calls conducted among a subset of the non-responders were particularly unsuccessful in this study, and a good illustration of what people say they will do is often much different from what they will actually do. Though 68% of enrollees who received a reminder call agreed to return the written survey, only 18% actually did so, resulting in a small overall response rate increase (to 41%), but at a higher price per response ($42).

Conducting the phone survey with a subset of non-responders resulted in the highest response rate (52%). The cost per response to the phone surveys was also the highest at $48/response, but includes all the previous contact attempts by phone and phone, so it is likely that this price would be much lower without the initial mail and reminder calls attempts. The phone surveys were conducted among the most difficult to reach population in this study (those that had not responded to all previous contact attempts), so the response rate would likely have been even higher among a randomly selected population of adolescents. Most importantly, the phone surveys boosted the overall response by 20% resulting in a final response rate of 61%, substantially improving the validity of the overall study results.

This study was not designed to directly compare the outcome of different survey administration techniques, and the sequential nature of the methods used prevents direct cost comparisons. Rather, the purpose of this paper was to describe a real-world example of a study utilizing multiple sequential methods to increase response to a threshold high enough for survey results to be valid and accepted for publication.

These analyses do not directly address the effects of mixing survey modes (the data from the self-administered written surveys and interviewer administered telephone surveys), though variables possibly associated with differential survey completion were analyzed. In this study, there were no differences in the age group, sex, or contact month of those who completed the survey by mail; but the phone survey completers were slightly older and more likely to complete if they were contacted in April versus January. There is a lack of empirical studies among adolescents about the effects of mode-mixing on self-reported health, but recent studies show the effect of both mode (19) and survey setting (home versus school) (20) can affect the results of health surveys conducted among populations of adolescents. Experienced survey researchers also understand mode mixing may often be unavoidable in today's data collection environment, and that potential biases mode mixing may introduce must be overcome through better understanding and survey design (21).

This study adds to the existing survey methodology literature to help future health researchers use cost-effective solutions to improve survey response. High response rates are one of several goals for health researchers, and must be balanced with goals of maximizing data quality and generalizability. Previous studies have shown that sending advance mailings prior to conducting phone surveys (18, 22) and token cash incentives for adolescents (23) are cost-effective solutions to increasing participation in telephone surveys. Additional research designed to directly compare the cost of mailed versus phone survey methodology among adolescent populations could be a helpful addition to the existing literature, but in our experience, mailed surveys alone will not generate a high enough response to reach the minimum threshold (generally 60%) for results to be accepted for publication, limiting the ability of researchers to disseminate results from surveys with low response rates. The results from this study suggest that phone surveys are more effective than mailed surveys for healthcare delivery organizations to achieve a high enough response rate for valid results among community samples of adolescents.

Figure 2.

Cost per Completed Survey

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Supported by the following grants: NIH/NIMH 1 K23MH069814, University of Washington Royalty Research Fund #3862, Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center Steering Committee Award #24536-UW01, and the Group Health Community Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None of the authors have conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Groves RM, Couper M. Nonresponse in household interview surveys. Wiley; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, Lowry R, McManus T, Chyen D, Lim C, Brener ND, Wechsler H. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008 Jun 6;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R, Kwan I, Cooper R. Methods to increase response rates to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):MR000008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000008.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kempf AM, Remington PL. New challenges for telephone survey research in the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:113–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AddHealth: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. University of North Carolina: The Carolina Population Center; 2003. [2008 July 9]. Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2008: Overview . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. [2008 June 11]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/overviewbrochure_0708.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen SA, Grunbaum JA, Whalen L, Eaton D, Hawkins J, Ross JG. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004 Sep 24;53(RR-12):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton DK, Lowry R, Brener ND, Grunbaum JA, Kann L. Passive versus active parental permission in school-based survey research: does the type of permission affect prevalence estimates of risk behaviors? Eval Rev. 2004 Dec;28(6):564–77. doi: 10.1177/0193841X04265651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC Health Risk Behaviors Among Adolescents Who Do and Do Not Attend School --United States. 1992 MMWR [serial on the Internet] 1994;43(08) Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00025174.htm. [PubMed]

- 10.Guttmacher S, Weitzman BC, Kapadia F, Weinberg SL. Classroom-based surveys of adolescent risk-taking behaviors: reducing the bias of absenteeism. Am J Public Health. 2002 Feb;92(2):235–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weitzman BC, Guttmacher S, Weinberg S, Kapadia F. Low response rate schools in surveys of adolescent risk taking behaviours: possible biases, possible solutions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003 Jan;57(1):63–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodgate RL, Edwards M. Children in health research: a matter of trust. J Med Ethics. 2010 Apr;36(4):211–6. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.031609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GHC. Group Health Overview [2009 January 7];GHC. 2010 Available from: http://www.ghc.org/about_gh/co-op_overview/index.jhtml.

- 14.Richardson LP, Rockhill C, Russo JE, Grossman DC, Richards J, McCarty C, McCauley E, Katon W. Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a Brief Screen for Detecting Major Depression Among Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010 Apr 5; doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bird HR, Andrews H, Schwab-Stone ME, Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS) Global measures of impairment for epidemiologic and clinical use with children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1996 Jan;6:295–307. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003 Nov;41(11):1284–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etter JF, Cucherat M, Perneger TV. Questionnaire color and response rates to mailed surveys. A randomized trial and a meta-analysis. Eval Health Prof. 2002 Jun;25(2):185–99. doi: 10.1177/01678702025002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camburn D, Lavrakas P, Battaglia M, Massey J, Wright R. Using Advance Respondent Letters in Random-Digit-Dialing Telephone Surveys. American Statistical Association Proceedings: Section on Survey Research Methods. 1995:969–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erhart M, Wetzel RM, Krugel A, Ravens-Sieberer U. Effects of phone versus mail survey methods on the measurement of health-related quality of life and emotional and behavioural problems in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brener ND, Eaton DK, Kann L, Grunbaum JA, Gross LA, Kyle TM, Ross JG. The Association of Survey Setting and Mode with Self-Reported Health Risk Behaviors among High School Students. Public Opin Q2006. 2006 September 1;70(3):354–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillman DA. Why choice of survey mode makes a difference. Public Health Rep. 2006 Jan-Feb;121(1):11–3. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hembroff LA, Rusz D, Rafferty A, McGee H, Ehrlich N. The Cost-Effectiveness of Alternative Advance Mailings in a Telephone Survey. Public Opin Q2005. 2005 January 1;69(2):232–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinson BC, Lazovich D, Lando HA, Perry CL, McGovern PG, Boyle RG. Effectiveness of monetary incentives for recruiting adolescents to an intervention trial to reduce smoking. Prev Med. 2000 Dec;31(6):706–13. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]