Abstract

Low-income, uninsured immigrants are burdened by poverty and a high prevalence of trauma exposure, and thus are vulnerable to mental health problems. Disparities in access to mental health services highlight the importance of adapting evidence-based interventions in primary care settings that serve this population. In 2005, The Montgomery Cares Behavioral Health Program (MCBHP) began adapting and implementing a collaborative care model for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders in a network of primary care clinics that serve low-income, uninsured residents of Montgomery County, Maryland, the majority of whom are immigrants. In its 6th year now, the program has generated much needed knowledge about the adaptation of this evidence-based model. The current article describes the adaptations to the traditional collaborative care model that were necessitated by patient characteristics and the clinic environment.

Keywords: immigrants, collaborative care, poverty, trauma, primary care clinic, Montgomery Cares Behavioral Health Program

Ana is a 45-year-old recent immigrant from El Salvador. She left her home country to escape an abusive husband, and because she could not afford to support her family on her own. At present, she works two jobs to support herself and her three children. They rent part of a basement and are struggling to get by financially. Ana frequently experiences feelings of sadness and hopelessness. She also reports flashbacks of childhood physical abuse and wartime atrocities that she witnessed in her home country. These concerns came to the attention of her primary care provider when she became tearful during a recent appointment when describing her chronic sleep difficulties [Composite fictitious case].

Immigrants and Mental Health

Immigration is an undeniably stressful experience (Hattar-Pollara, & Meleis, 1995; Levitt, Lane, & Levitt, 2005; Tang, Oatley, & Toner, 2007; Yakhnich, 2008). Immigration may be a dangerous or violent experience, especially if immigrants enter the United States illegally, and it most certainly involves separation from one's primary support system, culture, and way of life (Cavazos-Rehg, Zayas, & Spitznagel, 2007; Hattar-Pollara & Meleis, 1995). Moreover, once in the United States, undocumented immigrants, with low educational levels, low literacy, and language barriers are at even higher risk for all of the additional stressors that accompany poverty, such as food insecurity and hunger, housing instability, and compromised health status (Bassuk & Donelan, 2003). Poverty is also associated with increased risk for trauma and violence and their mental health impact (Bachman, & Saltzman, 1995; Chen et al., 2007; Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 2001; Sorenson, Upchurch & Shen, 1996). Given this accumulation of stressors, it is not surprising that low-income immigrants are at risk for mental illness that severely compromises their ability to function and to develop coping skills for ongoing stress.

The current article describes an adaptation of an evidence-based collaborative care model in primary care clinics serving low-income uninsured immigrants. Specifically, this article will address the following questions: (a) Can a collaborative care model be implemented in these settings? and (b) What adaptations of the model have been made to meet the needs of the primary care settings serving uninsured immigrants?

Effectively Engaging the Population for Treatment

Due to significant disparities in access to, use of, and quality of mental health services (Abe-Kim et al., 2007; Alegria et al., 2006; Cook, McGuire, & Miranda, 2007; Miranda, McGuire, Williams, & Wang, 2008; Stockdale, Lagomasino, Siddique, McGuire, & Miranda, 2008; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001), it is unlikely that an immigrant with a mental health problem, who may also be poor, uninsured, and uninsurable, will easily obtain services from a public or private mental health setting (Jackson et al., 2007; Nadeem et al., 2007; O'Mahony & Donnelly, 2007). Where then, do low-income immigrants tend to seek care, and where do they have access to needed services? In general, only a small proportion of all individuals with a mental health disorder seek care in specialty mental health settings; low-income individuals are even less likely to seek care in these settings. The United States' federally qualified community health centers (FQHCs; Health Center Consolidation Act, Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act) provide primary care services to uninsured and underinsured individuals in a number of locations. Where FQHCs are not established, private organizations, counties, and other municipalities have often developed clinics or mechanisms of funding to provide a basic level of primary care to indigent populations. Low-income uninsured populations, including immigrants, seek care for their health problems in these settings, and it is in these settings that their mental health problems are most likely to be discovered (Lazear, Pires, Isaacs, Chaulk, & Huang, 2008; Schraufnagel, Wagner, Miranda, & Roy-Byrne, 2006).

From a public health perspective, primary care settings offer the most promise for identifying and providing treatment to a significant proportion of the population with mental health problems (Burns, Ryan Wagner, Gaynes, Wells, & Schulberg, 2000; Simon, 2002), as opposed to specialized treatment for a select few in specialty mental health settings. Already, for the general U.S. population, primary care settings have become the de-facto treatment setting for common mental health disorders, with primary care providers delivering the majority of treatment (Regier et al., 1993). Prevalence estimates suggest that 20-25% of primary care patients suffer from depression or an anxiety disorder or both (Mergl et al., 2007), with some studies yielding even higher estimates (Alim et al., 2006; Mauksch et al., 2001; McQuaid, Stein, Laffaye, & McCahill, 1999). The prevalence of current posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in primary care samples is estimated to be between 9-23% (Gillock, Zayfert, Hegel, & Ferguson, 2005; Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan, & Löwe, 2007; Liebschutz et al., 2007; Magruder et al., 2005; McQuaid, Pedrelli, McCahill, & Stein, 2001; Stein, McQuaid, Pedrelli, Lenox, & McCahill, 2000; Walker et al., 2003). PTSD is the most common anxiety disorder (Kroenke et al., 2007), and about one third of depressed patients in primary care also meet criteria for PTSD (Campbell et al., 2007; Gerrity, Corson, & Dobscha, 2007; Green et al., 2006).

Despite the high level of need, treatment for mental health disorders in primary care settings is often inadequate. There are three important junctures at which typical treatment in primary care falls short. First, patients with mental health disorders are frequently not identified (Perez-Stable, Miranda, Muñoz, & Ying, 1990). Despite the ready availability of screening tools to assist in the identification of patients with common mental disorders, they are often not used in the primary care setting (e.g., Muñoz, McQuaid, González, Dimas, & Rosales, 1999). Second, once identified as having a mental health disorder, patients are rarely adequately evaluated and often, a correct diagnosis is not established (Perez-Stable et al., 1990). Establishing the correct diagnosis is essential to determining the right course of treatment. Third, patients rarely receive adequate treatment (Simon, 2002). This is largely because of the inability of most primary care providers (PCPs) to sufficiently monitor patients' adherence and response to treatment and to make changes in treatment when necessary in order to achieve and sustain long-term improvement. Treating mental health disorders in indigent care settings is further complicated by additional challenges including limited access to medications, overburdened staff, and complex patient presentations (National Association of Community Health Centers, 2005).

The Collaborative Care Model

Evidence-based models of care have been developed to treat common mental health disorders in primary care settings and to avoid the common shortcomings of typical mental health treatment in primary care. Collaborative care models, which provide assessment and treatment of depression and anxiety disorders by augmenting and supporting PCPs' capacity to treat common mental health problems in the primary care setting, have considerable empirical support (Hunkeler et al., 2006; Katon, Unützer, & Simon, 2004; Roy-Byrne, Katon, Cowley, & Russo, 2001, Unützer et al. 2002). Typically, a collaborative care model involves the addition of one or more mental health or allied health professionals (e.g., care managers) to the primary care clinic staff to provide auxiliary services (e.g., assessment, psychoeducation, referral, patient tracking). Collaborative care models also include consultation by a psychiatrist who provides caseload supervision and emergency backup (Katon & Seelig, 2008). As the name suggests, collaborative care models are characterized by regular contact and feedback among all individuals involved in the patients' care (Neumeyer-Gromen, Lampert, Stark, & Kallischnigg, 2004), often coordinated by the care manager.

A meta-analysis of 37 randomized controlled trials of collaborative care for depression in primary care showed that collaborative care significantly improved depression outcomes over control conditions, and that these effects were evident for up to five years (Gilbody, Bower, Fletcher, Richards, & Sutton, 2006). In addition to having a significant effect on clinical and functional outcomes, collaborative care models have been shown to be associated with increased patient and provider satisfaction and increased patient adherence to the mental health treatment regimen (Katon & Seelig, 2008; Neumeyer-Gromen et al., 2004). They are also cost efficient (Katon et al., 2005; Katon & Seelig, 2008). Gilbody et al. (2006) concluded that, as of the year 2000, there was sufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of collaborative care and recommended its dissemination.

The majority of the research on collaborative care has been done with insured patient populations who have more resources and greater access to mental and physical health services than is typical of uninsured patient populations. Efforts to disseminate collaborative care have been undertaken by several large, resourced systems of care including the Veterans Administration, Kaiser Permanente, and the Bureau of Primary Care's clinic system (Katon & Unützer, 2006). There have been a limited number of reports of collaborative care models that have been implemented in settings that serve low-income, uninsured populations (V. Little, personal communication, January 7, 2009; Mauksch et al., 2007). Mauksch et al. (2007) completed a review of charts before and after implementation of a collaborative care program in a private, nonprofit primary care clinic that serves low-income, uninsured patients and found that the quality of mental health care improved with the implementation of the collaborative care program. However, there are few reports on the implementation and effectiveness of such models in primary care settings that serve vulnerable populations such as low-income immigrants.

In 2005, The Montgomery Cares Behavioral Health Program (MCBHP) began adapting and implementing a collaborative care model for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders in a network of primary care clinics that serve low-income, uninsured residents of Montgomery County, Maryland, the majority of whom are immigrants. In its sixth year now, the program has generated much needed knowledge about the adaptation of this evidence-based model. The current article addresses two key questions, which have important implications for the adaptation and implementation of evidence based mental health programs in settings that treat vulnerable populations, such as uninsured immigrants. The questions include (a) Can a collaborative care model be implemented in these settings? and (b) What adaptations of the model have been made to meet the needs of the primary care settings serving uninsured immigrants? Although the results presented are primarily descriptive, data is presented when possible. Unless otherwise noted, the data presented is from data captured by the clinics' electronic medical record from July 2009 to June 2010.

Can a Collaborative Care Model be Implemented in Primary Care Settings that Serve Uninsured Immigrants?

Brief History of the MCBHP

In 2005, in coordination with a large expansion of primary care funding for the low-income uninsured population, the Montgomery County (Maryland) Council allocated funding for a behavioral health pilot to treat commonly occurring mental health disorders in the primary care settings serving these patients. The pilot was designed by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), the Primary Care Coalition of Montgomery County, MD, Inc., and the Center for Mental Health Outreach in Georgetown University's Department of Psychiatry. Following approximately 6 months of planning, the program was implemented in the first clinic in December 2005. Subsequent clinics were added in October 2006 and February 2008. The MCBHP expects to expand beyond the current three clinics as funding becomes available.

Essential Elements of Traditional Collaborative Care Retained by the MCBHP

The MCBHP's model of care is designed to support the efforts of the PCPs to efficiently treat common mental health disorders in the indigent care primary care setting. This has been achieved by establishing formal processes and practices to avoid the common pitfalls of typical treatment in primary care related to identification, evaluation, and adequate treatment. Thus, the MCBHP seeks to (a) identify patients with mental health needs, (b) evaluate patients with identified needs to determine the appropriate level of care, and (c) provide appropriate treatment which can include medication, support, social service intervention, supportive intervention such as behavioral activation, a low-intensity psychotherapy (Beck, 1976; Jacobson et al., 1996), or referral to primary psychiatric or substance abuse services.

The MCBHP incorporates the essential components of collaborative care. Traditional collaborative care models seek to identify as many patients as possible with a target mental health diagnosis and treat them with appropriate interventions, without expending a great deal more PCP time and effort in the process. In this model, the primary care provider remains responsible for the medical treatment of mental health disorders. Their capacity to provide this treatment is enhanced by collaboration with a care manager and a consulting psychiatrist. Care managers expand the capacity of the PCP by providing auxiliary services including screening, evaluation, symptom and adherence monitoring, patient education and activation, and, in some cases, psychotherapy (Katon, Unützer, & Simon, 2004; Katon, Von Korff, Lin, & Simon, 2001). The psychiatrist provides consultation to the care manager and primary care providers. Coordination of care is facilitated by frequent communication among the primary care team and the care manager.

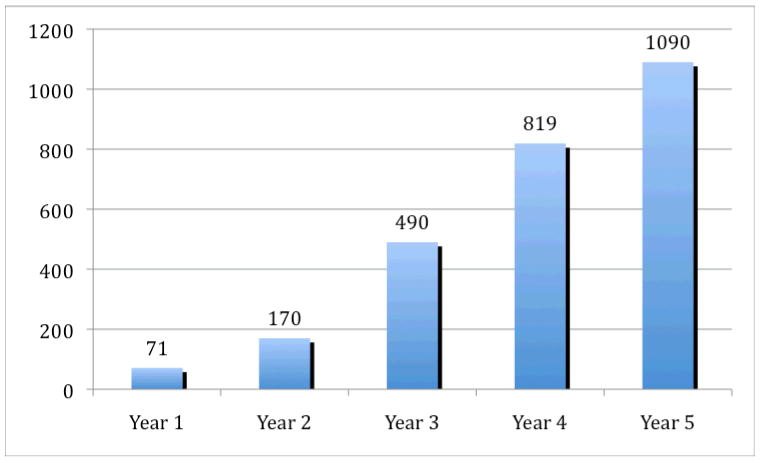

Because of the successful implementation and early expansion of the program, the MCBHP has seen a sharp increase in the number of patients treated (See Figure 1). This increased utilization may also reflect the perceived acceptability of the program among the target population. The collaborative care model utilized by the MCBHP has high fidelity to the core ingredients of traditional collaborative care. However, both the population served and the clinical settings themselves have necessitated important adaptations.

Figure 1.

Number of patients treated by the MCBHP by year of the program.

What Adaptations of the Model Have Been Needed?

Modifications were made to the traditional collaborative care model by the MCBHP during its first 3 years, 2005-2008. These modifications were shaped by two major factors: (a) the characteristics of the population served and (b) the characteristics of the clinic environment. Some of these modifications were envisioned at the outset of the program, and others have been made over the course of the program in order to maximize clinical processes and outcomes. The adaptations were informed by multiple theories and conceptual approaches including Maslow's hierarchy of needs, trauma theory, and the framework of public health. Briefly, Maslow's hierarchy of needs suggests that deficiencies in lower level needs (e.g., physiological) must be mitigated prior to addressing higher needs (love/belonging, esteem; Maslow, 1943). Trauma theory describes the profound and multifaceted impact of the exposure to trauma and violence (Herman, 1992; McCann & Pearlman, 1990). Finally, a public health framework stresses the importance of prevention and the treatment of the largest number of individuals possible utilizing cost-efficient strategies (e.g., Brulde, 2008; Robles, 2004; Schneider, 2006). A description of the population served by the MCBHP clinics and the population-related changes, as well as a description of the clinic contexts and the context-related changes follows.

Population Served

Description of the population served

From July 2009 - June 2010, the MCBHP treated 1090 unique patients. Seventy-eight percent were female and 78% percent were Latino. Eighty-nine percent reported being foreign born and were primarily documented or non-documented immigrants. A small minority of U.S. citizens was seen by the clinics as a stop-gap measure while public benefits were being accessed. The immigrants represented more than 50 different countries of origin with the most frequent being El Salvador (34.5%), Peru (10.6%), Honduras (7.2%), and Guatemala (5.6%). Although Spanish-speaking immigrants predominated the clinic populations at each of the three clinics, there was some interclinic variability in the proportion of nonimmigrants and immigrants from outside of Central and South America. By definition of being eligible for services at the clinics, all patients were low-income and did not have or were not eligible for health insurance by virtue of their legal status in the US. Trauma exposure among this patient population was high.1 Alterations to the evidence-based model of collaborative care were necessitated by characteristics of the target population including their high degree of poverty and high prevalence of trauma exposure. These adaptations impacted program staffing, selection of target diagnoses, and interventions offered.

Impact of patient population on program staffing

Information specific to the target patient population was used to determine the staff needed for the MCBHP. During the initial phase of the project, it was evident that it would be necessary to address basic social needs (e.g., food, clothing, shelter, employment) in addition to mental health needs. Consistent with Maslow's hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1943), it was expected that without addressing basic physiological and safety needs, it would be difficult to address mental health needs. Although not included in the evidence-based collaborative care model, a family support worker was added to the staffing plan at each clinic. The family support worker is responsible for identifying social service needs and connecting patients to needed resources. From July 2009 - June 2010, the MCBHP documented 357 social service interventions across the three clinics. This included referrals for food, employment, housing, legal services, clothing, and education or language services.

The target population also shaped other requirements of the staff hired by the program. Early on, it became clear that different skill sets and knowledge would be important. First, staff needed to be fluent in Spanish to work effectively with the patient population. Second, staff needed to understand the care management model and be comfortable working in the primary care setting. Third, staff needed to have an understanding of the evaluation and treatment of mental disorders. After several waves of hiring, it became clear that language fluency and an understanding of care management and comfort in primary care settings were vital. Although knowledge of mental health would seem to be crucial, this was recognized as secondary and more easily taught.

The care manager positions were initially intended to be filled by nurses; however, given the shortage of bilingual nurses, the program broadened the position to include bilingual social workers. The social workers have been able to meet the demands of the care manager role and add the benefit of being able to provide psychotherapy.

High prevalence of trauma

It was also recognized early on that because of the high level of poverty and the high number of immigrants from war-torn regions (e.g., Central America), there would be a high prevalence of trauma exposure related to both interpersonal and political violence among the patient population, which also included a number of torture survivors. This affected strategic decisions about both target diagnoses and treatment. Typical collaborative care programs address one diagnosis (e.g., depression). This was deemed not feasible for the MCBHP, in large part because of the expected high levels of trauma. Because trauma has multiple potential clinical outcomes (e.g., Ford, Stockton, Kaltman & Green, 2006; Grant, Beck, Marques, Palyo, & Clapp, 2008; Neria et al., 2008), having multiple diagnostic targets was more consistent with the needs of the patient population. Thus, the MCBHP was designed with four diagnostic targets: (a) depression, (b) generalized anxiety disorder, (c) PTSD, and (d) panic disorder. In further support of multiple diagnostic targets, evidence suggests that patients with comorbid depression and PTSD may take longer to improve and may continue to have residual symptoms (Green et al., 2006; Hegel et al., 2005), suggesting the need to track multiple disorders.

In addition to support, monitoring, and behavioral activation, the principal intervention of the program was pharmacological intervention. However, many patients with trauma requested psychotherapy. This request was consistent with the observations of the team that many patients with trauma histories continued to experience functional disturbances (e.g., disrupted relationships) even in the context of improved symptomatology. The social worker care managers offered limited psychotherapy to these patients. Whenever possible, the MCBHP also developed relationships with other organizations that provided psychotherapy at low or no charge, including torture survivor clinics and victims' assistance programs. In the future, the MCBHP also plans to implement a psychoeducation or support group for women with trauma exposure.

Clinic Environment

Description of the clinics

The three clinics in which the MCBHP is implemented vary widely in their structure, funding mechanism, and staffing. The first clinic is a freestanding 501(c)3 corporation that began as a county-funded minority health initiative. This is one of the largest clinics serving uninsured patients in the county and offers evening and weekend hours. Health care is provided by paid and volunteer PCPs and specialists. The majority of the patients seen at this clinic are immigrants from Central and South America. The clinic treats approximately 4,400 patients per year. The second clinic is a hospital-based clinic, primarily staffed by paid professionals. This clinic was founded to provide a medical home for frequent utilizers of the hospital's emergency room and uninsured hospital discharges. Although the majority of patients are Latino immigrants, this clinic sees a more diverse immigrant population. The clinic treats approximately 4000 patients per year. The third clinic is an independent, 501(c)3 corporation that was established by a Catholic parish and based on the traditional “free clinic” model. There is a small paid administrative and support staff. Health care is provided by volunteer PCPs and specialists and a volunteer medical director. The clinic operates 3 days a week and, although regularly staffed by volunteer physicians, lacks continuity of care between patient and provider. The majority of the patients seen at this clinic are immigrants from Central and South America. The clinic treats approximately 2,200 patients per year. In their broader context, the clinics also function within a larger community that has limited mental health resources for the uninsured population. These characteristics of the clinics and their broader context have led to important adaptations of the intervention model.

Clinic structure

The initial intention of the MCBHP was to implement the same program in each clinic. This proved to be impossible given the varying clinic structures and highlighted the importance of flexibility in the treatment model. Collaborative care models are dependent upon having a stable set of PCPs. Without this, the varying level of training and comfort in treating mental health problems among the PCPs can be problematic. One of the clinics in which the MCBHP was implemented had significant PCP turnover and, at one point, this left almost no PCPs to work with the program. To address this deficit, the MCBHP identified a PCP to temporarily hold weekly clinics in which she saw all of the MCBHP patients. This stop-gap measure allowed the MCBHP to continue treating patients. The model returned to its typical format when more stability in the PCP staffing returned. Another clinic is staffed almost exclusively by volunteer PCPs, who work regularly but often infrequently. This made training and PCP engagement very challenging. To overcome this limitation, the MCBHP contracted with a resident psychiatrist who, as part of his training, staffed the clinic and saw the MCBHP patients during the acute phase of care. Although the resident managed the patient's mental health needs during the acute phase of care, all notes were provided to the PCPs and the PCPs took over care beyond the typically brief, acute phase of treatment. Having a resident on-site also allowed for additional resources for evaluation and treatment of more complex patients.

Expanded focus

The MCBHP clinics are situated in a community with extremely limited mental health resources for the uninsured immigrant population. Thus, the program expanded its focus beyond that of a typical collaborative care model, which focuses only on disorders that are easily treated within the primary care setting. The MCBHP takes more of a public health approach, providing mental health services to as many patients as possible, given that for most patients the MCBHP provides their only opportunity to receive services. This model expansion led to a procedure whereby patients were evaluated and then placed in one of three different treatment groups. The treatment group assignment then directed the interventions that are offered.

Briefly, the first group included patients who met diagnostic criteria for depression, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, or panic disorder and who are appropriately treated in the primary care setting. This group was the largest group of patients treated and was closest to the typical target population of collaborative care models. The second group included patients who had subthreshold levels of symptoms or possibly no symptoms but had social service or support needs. These patients were offered supportive and social service interventions. This group was an important focus of the MCBHP because it was hoped that intervening with these patients would prevent their symptoms from increasing into the diagnostic range. The third group included patients with serious mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) or an alcohol or substance use disorder that were not appropriately treated in the primary care setting. These patients were referred to primary mental health or substance abuse services or both. However, because there were limited services available to the uninsured immigrant population, the MCBHP expended considerable effort on this group of patients. In addition to working with local treatment programs to identify an appropriate treatment setting, these patients were also offered social service interventions and, at times, stop-gap treatment of their mental disorder. Approximately 60% of patients fell within the group of patients who were offered treatment for a mental disorder in addition to supportive and social service interventions. Among these patients, comorbidity of diagnoses is common.2 Twenty-five percent of patients fell within the subthreshold group who were offered only supportive and social service interventions and 15% fell within the serious mental illness group.

Discussion

Mental health treatment programs in primary care settings have the potential both to offer effective treatments to a large segment of the population and, importantly, to mitigate disparities in access to mental health care for low-income, minority patients. Low-income, uninsured immigrants may represent a group at particular risk for mental disorders because of poverty and a high prevalence of trauma exposure. Given the multiple barriers to accessing mental health services for this population, programs such as the Montgomery Cares Behavioral Health Program (MCBHP) are an extremely important resource. Without them, low-income, uninsured immigrant populations will have almost no access to needed mental health care. Therefore, research on the adaptation and implementation of cost-efficient evidence-based practices in settings such as primary care that serve these populations is vital.

Because of their extensive empirical support and evidence of cost efficiency (Gilbody et al., 2006; Katon & Seelig, 2008; Neumeyer-Gromen et al., 2004), the MCBHP chose to utilize a collaborative care model for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders when given the funds to conduct a pilot to treat common mental disorders in the primary care setting. To date, the MCBHP has implemented an adapted collaborative care model in three primary care clinics which serve a low-income, uninsured, and largely immigrant population. The collaborative care model was implemented with high fidelity to the core, active components of the traditional collaborative care model (Katon and Seelig, 2008), including a team-based approach, allied health professionals that coordinate care, frequent symptom monitoring of patients with objective assessments, and intensive care management to identify problems in adherence and to maintain treatment engagement. The MCBHP has steadily increased the number of patients it has treated during the 6 years of the program.

The patient population targeted by the MCBHP and the clinical settings in which the MCBHP operates necessitated several initial modifications to the collaborative care model as well as flexibility to meet the changing needs of the dynamic clinic environment. Modifications made were in response to the poverty and the high level of trauma exposure that characterized the patient population. The poverty experienced by the patient population suggested that an emphasis on social service provision in addition to mental health treatment would be essential. To accommodate this, the collaborative care team was expanded to include a family support worker at each clinic to focus on meeting the social service needs of the patients served by the program. This modification was crucial in terms of meeting the priorities of the patients, which often related to basic needs rather than mental health treatment, and also in terms of engaging patients in the program who might otherwise have been reluctant to seek mental health care. The high prevalence of trauma among the patient population also led the program to choose multiple target diagnoses, instead of just one as in most traditional collaborative care models. It was deemed essential to identify and monitor PTSD, for example, as multiple studies have shown that patients with comorbid PTSD and depression may take longer to achieve symptom reduction and may be more likely to have residual symptoms following treatment as compared to patients with depression alone (Green et al., 2006; Hegel et al., 2005). Addressing needs associated with poverty, as well as the impact of trauma exposure, will be essential for any program that works with a similar patient population.

The clinic environments and their larger context within the county led to additional adaptations. Changes in the staffing of the collaborative care teams, as well as shifts in the treatment model, have been made in response to clinic needs. One clinic underwent such significant PCP turnover that the MCBHP had to identify its own PCP to maintain patients on their treatment while the clinic resolved its staffing issues. For this brief period of time, the program acted as a mental health clinic within a primary care clinic until the staffing issues were resolved and the collaborative care approach was reinstituted. Without this flexibility, many patients would have been stranded without care and the MCBHP's relationship with that clinic might have been irreparably damaged. Another clinic's all volunteer PCP team presented additional challenges. Because of the difficulty of engaging this large and sporadically working team of PCPs in training, education, and practice modification, the MCBHP eventually hired a resident psychiatrist to join the collaborative care team. The resident treated the MCBHP patients during the acute phase of care before transferring patients back to the PCP for maintenance care, while also training the PCPs in an ongoing way through modeling, consultation, and frequent communication.

Finally, the lack of community-based mental health care for the MCBHP's patient population encouraged the program to reframe the scope of the services it provides much more broadly than a traditional collaborative care model program. As a result, the MCBHP provides not only the traditional collaborative care services to patients with specific diagnoses, but also provides intervention to patients with subthreshold symptoms and provides assessment and limited interventions for patients with serious mental illness. Although the MCBHP expends most of its efforts on patients with diagnosable depression or anxiety disorders, taking this public health approach was deemed necessary as many patients would otherwise not receive any services. The experience of the MCBHP is likely to be common among groups that seek to transport evidence-based models into real world clinic settings that do not resemble the clinical environments in which the interventions were developed and tested. Thus, this type of flexibility in stretching and changing the model will likely be essential in future efforts.

Implications for Policy

A critical concern for the widespread dissemination of any effective program or intervention is assuring that patients can have access to those programs. Specifically, for patients without insurance and with limited resources, there are significant barriers to both mental and physical health care. Implementation of collaborative care models has been limited in large part because of the presence and structure of mental health financing. Mental health care is largely funded through carved out insurance programs, which separate care for mental and physical health care. This separation has lead to difficulties receiving mental health care outside of the specialty mental health setting. Thus, addressing these access barriers is a key challenge for policy makers. The MCBHP was funded in the same way that health care is funded for these patients within the county, via a direct appropriation, and thus did not have to resolve these financing barriers at the outset. However, the program has brought to light a critical lack of basic mental health services for individuals who are not citizens. One of the most compelling findings of this program is that with appropriate sustained financing, patients can receive access to care. In other settings, addressing the issue of sustainability becomes the rate-limiting factor to the provision of care and requires addressing health care financing, privacy and regulatory concerns before a care system can be implemented. Having the support of lawmakers and policy makers contributed significantly to the success of this program.

Conclusion

In summary, because of significant mental health care disparities, an understanding of how best to adapt and implement evidence-based strategies for treating the mental health problems of low-income, uninsured immigrants in primary care settings is extremely important. The MCBHP has demonstrated that it is possible to implement a cost-efficient and evidence-based treatment model. Although adaptations and flexibility in the model were essential, the key components of traditional collaborative care were preserved. It is hoped that the experience of the MCBHP can be used to inform the adaptation and implementation of similar programs that treat low-income, uninsured patients. Without such programs, the needs of these multiply burdened patients will go unmet.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors wish to acknowledge Junfeng Sun, who performed statistical analyses that were part of an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Although not systematically captured by the electronic medical record, data from a 2007-2008 program evaluation suggested that 63% (overall) or 55%-74% (by clinic) of the patients served reported trauma exposure on a brief trauma screen.

Data from a 2007-2008 program evaluation suggested that 55% of patients met criteria for more than one target disorder.

Contributor Information

Stacey Kaltman, Georgetown University Medical Center.

Jennifer Pauk, Primary Care Coalition of Montgomery County, MD Inc..

Carol L. Alter, Georgetown University Hospital

References

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer MS, Alegria M. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Cao Z, McGuire TG, Ojeda VD, Sribney B, Woo M, Takeuchi D. Health insurance coverage for vulnerable populations: Contrasting Asian American and Latinos in the United States. Inquiry. 2006;43:231–254. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_43.3.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alim T, Graves E, Mellman TA, Aigbogun N, Gray E, Lawson W, Charney DS. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in an African American primary care population. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98:1630–1636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman R, Saltzman LE. Violence against women: Estimates from the redesigned survey (NCJ 154348) Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Donelan B. Social deprivation. In: Green BL, Friedman MJ, de Jong JTVM, Solomon SD, Keane TM, Fairbank JA, Donelan B, Frey-Wouters E, editors. Trauma interventions in war and peace. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Brulde B. Inequity, inequality, and the distributive goals of public health. International Journal of Public Health. 2008;53:5–6. doi: 10.1007/s00038-007-0234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Ryan Wagner H, Gaynes BN, Wells KB, Schulberg HC. General medical and specialty mental health service use for major depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2000;30:127–143. doi: 10.2190/TLXJ-YXLX-F4YA-6PHA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu CF, Yano EM, Kirchner JE, Chan D, Chaney EF. Prevalence of depression PTSD comorbidity: Implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:711–718. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Zayas LH, Spitznagel EL. Legal status, emotional well-being and subjective health status of Latino immigrants. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99:1126–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Keith VM, Leong KJ, Airriess C, Li W, Chung KY, Lee CC. Hurricane Katrina: Prior trauma, poverty and health among Vietnamese-American survivors. International Nursing Review. 2007;54:324–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, McGuire T, Miranda J. Measuring trends in mental health care disparities, 2000-2004. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1533–1540. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark C, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: A multilevel analysis. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Stockton P, Kaltman S, Green BL. Disorders of extreme stress (DESNOS) symptoms are associated with type and severity of interpersonal trauma exposure in a sample of healthy young women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1399–1416. doi: 10.1177/0886260506292992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrity M, Corson K, Dobscha SK. Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in VA primary care patients with depression symptoms. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:1321–1324. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0290-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: A cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillock KL, Zayfert C, Hegel MT, Ferguson RJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care: Prevalence and relationships with physical symptoms and medical utilization. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2005;27:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant DM, Beck JG, Marques L, Paylo SA, Clapp JD. The structure of distress following trauma: Posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:662–672. doi: 10.1037/a0012591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Krupnick JL, Chung J, Siddique J, Krause ED, Revicki D, Miranda J. Impact of PTSD comorbidity on one-year outcomes in a depression trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:815–835. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattar-Pollara M, Meleis AI. The stress of immigration and the daily lived experiences of Jordanian immigrant women in the United States. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1995;17:521–539. doi: 10.1177/019394599501700505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegel MT, Unützer J, Tang L, Areán PA, Katon W, Noël PH, Lin EH. Impact of comorbid panic and posttraumatic stress disorder on outcomes of collaborative care for late-life depression in primary care. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:48–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JL. Trauma and recovery. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, Williams JW, Kroenke K, Lin EH, Unützer J. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. British Medical Journal. 2006;332:259–263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Martin LA, Wiliams DR, Baser R. Use of mental health services and subjective satisfaction with treatment among Black Caribbean immigrants: Results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:60–67. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, Addis ME, Koerner K, Gollan JK, Prince SE. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Schoenbaum M, Fan MY, Callahan CM, Williams J, Jr, Hunkeler E, Unützer J. Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1313–1320. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Seelig M. Population-based care of depression: Team care approaches to improving outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2008;50:459–467. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318168efb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Unützer J. Collaborative care models for depression: Time to move from evidence to practice. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:2304–2306. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Unützer J, Simon G. Treatment of depression in primary care: Where we are, where we can go. Medical Care. 2004;42:1153–1157. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G. Rethinking practitioner roles in chronic Illness: The specialist, primary care physician, and the practice nurse. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2001;23:138–144. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazear KJ, Pires SA, Isaacs MR, Chaulk P, Huang L. Depression among low-income women of color: Qualitative findings from cross-cultural focus groups. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2008;10:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt MJ, Lane J, Levitt J. Immigration stress, social support, and adjustment in the first postmigration year: An intergenerational analysis. Research in Human Development. 2005;2:159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Liebschutz J, Saitz R, Brower V, Keane TM, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Averbuch T, Samet JH. PTSD in urban primary care: High prevalence and low physician recognition. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:719–726. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0161-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Davis L, Hamner MB, Martin RH, Arana GW. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2005;27:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50:370–396. [Google Scholar]

- Mauksch LB, Reitz R, Tucker S, Hurd St, Russo J, Katon WJ. Improving quality of care for mental illness in an uninsured, low-income primary care population. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauksch LB, Tucker SM, Katon WJ, Russo J, Cameron J, Walker E, Spitzer R. Mental illness, functional impairment, and patient preferences for collaborative care in an uninsured, primary care population. Journal of Family Practice. 2001;50:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann IL, Pearlman LA. Psychological trauma and the adult survivor: Theory, therapy, and transformation. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, McCahill ME, Stein MB. Reported trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression among primary care patients. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1249–1257. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid JR, Stein MB, Laffaye C, McCahill ME. Depression in a primary care clinic: The prevalence and impact of an unrecognized disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;55:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergl R, Seidscheck I, Allgaier AK, Moller HJ, Hegerl U, Henkel V. Depressive, anxiety, and somatoform disorders in primary care: Prevalence and recognition. Depression and Anxiety. 2007;24:185–195. doi: 10.1002/da.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, McGuire TG, Williams DR, Wang P. Mental health in the context of health disparities. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1102–1108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz RF, McQuaid JR, González GM, Dimas J, Rosales VA. Depression screening in a women's clinic: Using automated Spanish- and English-language voice recognition. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, Miranda J. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S.-born Black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1547–1554. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Community Health Centers. The Safety Net on the Edge. Washington, DC: National Association of Community Health Centers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Wickramaratne P, Gross R, Pilowsky DJ, Weissman MM. The mental health consequences of disaster-related loss: Findings from primary care one year after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Psychiatry. 2008;71:339–348. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumeyer-Gromen A, Lampert T, Stark K, Kallischnigg G. Disease management programs for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medical Care. 2004;42:1211–1221. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Mahony JM, Donnelly TT. The influences of culture on immigrant women's mental health care experiences from the perspectives of health care providers. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2007;28:453–471. doi: 10.1080/01612840701344464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Stable EJ, Miranda J, Muñoz RF, Ying YW. Depression in medical outpatients: Underrecognition and misdiagnosis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1990;150:1083–1088. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1990.00390170113024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles SC. A public health framework for chronic disease prevention and control. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2004;25:194–199. doi: 10.1177/156482650402500213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P, Katon W, Cowley DS, Russo J. A randomized effectiveness trial of collaborative care for patients with panic disorder in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:869–876. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MJ. Introduction to public health. 2nd. Boston, MA: Jones & Bartlett; Publishers: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schraufnagel TJ, Wagner AW, Miranda J, Roy-Byrne PP. Treating minority patients with depression and anxiety: What does the evidence tell us? General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE. Evidence review: Efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2002;24:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson S, Upchurch D, Shen H. Violence and injury in marital arguments: Risk patterns and gender differences. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:35–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care setting. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2000;22:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale SE, Lagomasino IT, Siddique J, McGuire T, Miranda J. Racial and ethnic disparities in detection and treatment of depression and anxiety among psychiatric and primary health care visits, 1995-2005. Medical Care. 2008;46:668–677. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181789496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TN, Oatley K, Toner BB. Impact of life events and difficulties on the mental health of Chinese immigrant women. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9:281–290. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity, supplement to mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, NIMH, NIH; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L Impact Investigators. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medial Association. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Katon W, Russo J, Ciechanowski P, Newman E, Wagner AW. Health care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:369–374. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakhnich L. Immigration as a multiple-stressor situation: Stress and coping among immigrants from the form Soviet Union in Israel. International Journal of Stress Management. 2008;15:252–268. [Google Scholar]