Abstract

α-Cobratoxin (Cbtx), the neurotoxin isolated from the venom of the Thai cobra Naja kaouthia, causes paralysis by preventing acetylcholine (ACh) binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). In the current study, the region of the Cbtx molecule that is directly involved in binding to nAChRs is used as the target for anticobratoxin drug design. The crystal structure (1YI5) of Cbtx in complex with the acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP), a soluble homolog of the extracellular binding domain of nAChRs, was selected to prepare an α-cobratoxin active binding site for docking. The amino acid residues (Ser182-Tyr192) of the AChBP structure, the binding site of Cbtx, were used as the positive control to validate the prepared Cbtx active binding site (root mean square deviation < 1.2 Å). Virtual screening of the National Cancer Institute diversity set, a library of 1990 compounds with nonredundant pharmacophore profiles, using AutoDock against the Cbtx active site, revealed 39 potential inhibitor candidates. The adapted in vitro radioligand competition assays using [3H]epibatidine and [125I]bungarotoxin against the AChBPs from the marine species, Aplysia californica (Ac), and from the freshwater snails, Lymnaea stagnalis (Ls) and Bolinus truncates (Bt), revealed 4 compounds from the list of inhibitor candidates that had micromolar to nanomolar interferences for the toxin binding to AChBPs. Three hits (NSC42258, NSC121865, and NSC134754) can prolong the survival time of the mice if administered 30 min before injection with Cbtx, but only NSC121865 and NSC134754 can prolong the survival time if injected immediately after injection with Cbtx. These inhibitors serve as novel templates/scaffolds for the development of more potent and specific anticobratoxin.

Keywords: α-cobratoxin, virtual screening, docking, neurotoxin, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

INTRODUCTION

Snake envenomation is still a health problem worldwide, especially in tropical countries. It has been estimated that global mortality from snake envenomation is up to 100,000 per year. In many cases, survivors are left with chronic functional disability from the necrotic effects of the venom, resulting in chronic ulceration, chronic renal failure, and neurological sequelae from intracranial hemorrhages and thromboses or even amputation.1-4 Snake venoms contain complex mixtures that consist of several toxic proteins with diverse biological activities. Venom from the Thai cobra Naja kaouthia contains paralytic “neurotoxin” activity, which acts on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors; cytolytic “cardiotoxin” activity, which acts on cell membranes, as well as phospholipase; and D-amino acid oxidase activities.5-7

α-Cobratoxin (Cbtx), a member of the long α-neurotoxin family, is obtained from the venom of Naja kaouthia (previously called Naja naja siamensis). Cbtx has 71 amino acid residues and 5 disulfide bridges.8 It consists of 3 finger-like loops: loops I, II, and III. It blocks nerve transmission by binding to the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) on the postsynaptic membranes of skeletal muscle and/or neurons, causing paralysis by preventing acetylcholine binding to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR).9 nAChR mediates excitatory transmission at the neuromuscular junction and in the central and peripheral nervous systems. The soluble acetylcholine-binding protein (AChBP) from the freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis (Ls) is a structural homologue of the extracellular ligand-binding domain of muscle-type and neuronal nAChRs.10,11 Recently, the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of Cbtx and the crystal structure of a Cbtx-AChBP complex (1YI5) have been reported.12-14 Since this initial discovery, the AChBP molecule has been identified in the marine species Aplysia californica (Ac) and the freshwater species Bolinus truncatus (Bt).15,16

The Thai cobra, N. kaouthia, is the most dangerous cobra in Thailand. It can be found in almost every part of the country. Currently, cobra envenomation is a serious problem for Thai farmers. The only remedy for a cobra bite is a monospecific antivenom produced by the Queen Saovabha Memorial Institute and the Thai Red Cross Society. The horse antivenom against N. kaouthia is very difficult to produce, expensive, and in short supply. Only 20% of the horses immunized with Thai cobra venom produce adequate neutralizing activity for antivenom production. Furthermore, the neutralizing activity considered adequate is in fact quite low.

Virtual screening has been widely used to discover new lead compounds for drug design.17 Successful studies have resulted in the discovery of molecules either resembling the native ligands of the specific targets or novel leads. Therefore, this study aimed to find a novel antidote of cobra venom by preventing α-cobratoxin from binding to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. The findings can aid in the development of new therapeutic treatment of snakebite in Thailand.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Lyophilized N. kaouthia venom was provided by the Queen Saovabha Memorial Institute and the Thai Red Cross Society (Bangkok, Thailand). Binding protein was provided by the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of California, San Diego. Antimouse scintillation proximity assay (SPA) was purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). All other chemicals were of reagent grade and purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). ICR mice were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center at Mahidol University (Salaya, Thailand). The tested 4 hits from virtual Screening were from the National Cancer Institute (NCI; http://dtp.nci.nih.gov).

Target preparation

A search for α-cobratoxin structures found 3 entries in the Protein Data Bank (PDB).18 1CTX19 and 2CTX20 were unbound α-cobratoxin crystal structures, and 1YI513 was a complex of Cbtx bound to the pentameric AChBP from Ls. The Cbtx from the α-cobratoxin/AChBP complex (1YI5) was selected as the Cbtx template for the validation study. Polar hydrogen atoms were added and Kollman charges were assigned to all atoms. The grid maps representing the Cbtx were calculated with AutoGrid. The dimensions of the grid were 60 × 88 × 86 grid points for 1YI5 and 86 × 60 × 88 for 1CTX and 2CTX, with a spacing of 0.375 Å between the grid points. The grid box was centered on the coordinates 118.056 × 160.484 × 64.991 for 1YI5 and 29.652 × 49.388 × 4.481 for 1CTX and 2CTX. Ser182-Tyr192 of AChBP from 1YI5 was selected to be the positive control because it is a contiguous peptide near the acetylcholine binding site. It was designed to have 9 rotatable bonds from the side chain single bonds of the residues and was redocked to validate the prepared α-cobratoxin active binding sites.

NCI diversity set

The NCI diversity set is a reduced set of 1990 compounds selected from the original NCI-3D structural database for their unique pharmacophores.21 All hydrogens were added and Gasteiger charges were assigned.22 Then the nonpolar hydrogens were merged. The rotatable bonds were assigned via AutoTors.23

Molecular docking

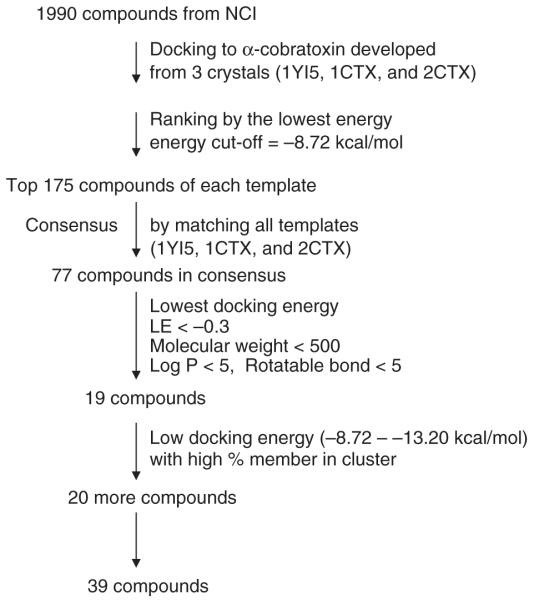

A virtual screening of the 1990 compounds was performed as per Figure 1. The program AutoDock Version 3.0.523 from the Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, CA) uses a Larmarckian genetic algorithm for docking flexible ligands into protein binding sites to explore the full range of ligand conformational flexibility with the rigid protein. The AutoDock run parameters used were as follows: for each compound in the library, the number of GA runs was 100, the population size was set to 150, and the maximum number of energy evaluations was increased to 10,000,000 per run. All other run parameters were kept at their default settings. The jobs were run on a 64-bit 576 processor LINUX cluster at the Scripps Research Institute. Final docked conformations were clustered using a tolerance of 2 Å root mean square deviation (RMSD). The lowest docking energy of the 100 dockings for each α-cobratoxin protein (1YI5, 1CTX, and 2CTX) was ranked. The top 175 compounds with the best docking energies of each protein were ranked and checked for consensus between the proteins and reduced to 77 compounds. The 77 compounds were further reduced to 19 compounds by selecting for ligand efficiency (LE) lower than −0.30 and with “drug-like” properties.24,25 For experimental testing, 20 additional compounds were included in the in vitro evaluation based on their low docking energy and high percent membership in the largest cluster. The total number of compounds in the binding study was 39 (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Virtual screening from in silico.

Table 1.

Selected Hits from Virtual Screening

| Edocking in Highest Clustering, kcal/mol |

%Member in Highest Cluster |

LE |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | NSC Number | MW, Da | Log P | RB | 1YI5 | 2CTX | 1CTX | 1YI5 | 2CTX | 1CTX | 1YI5 |

| 1 | 10458 | 482 | 3.57 | 7 | −9.64 | −9.78 | −10.20 | 28 | 21 | 57 | −0.28 |

| 2 | 12181 | 458 | 5.22 | 5 | −10.50 | −10.10 | −11.41 | 66 | 16 | 74 | −0.24 |

| 3 | 14410 | 444 | 0.35 | 4 | −12.11 | −10.81 | −11.31 | 69 | 43 | 55 | −0.33 |

| 4 | 17245 | 459 | 2.17 | 7 | −9.74 | −9.71 | −10.20 | 26 | 24 | 11 | −0.26 |

| 5 | 18877 | 406 | 4.62 | 4 | −10.89 | −9.56 | −10.5 | 29 | 55 | 26 | −0.32 |

| 6 | 23217 | 405 | 6.50 | 4 | −11.54 | −10.11 | −9.64 | 56 | 26 | 27 | −0.37 |

| 7 | 23904 | 524 | 2.85 | 7 | −11.00 | −6.68 | −10.60 | 28 | 57 | 18 | −0.29 |

| 8 | 36387 | 696 | 3.18 | 4 | −11.10 | −9.34 | −9.64 | 16 | 8 | 25 | −0.20 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 9 | 37245 | 467 | 4.33 | 4 | −11.45 | −9.19 | −11.55 | 54 | 20 | 53 | −0.31 |

| 10 | 42258 | 417 | 3.27 | 4 | −11.23 | −8.27 | −10.69 | 65 | 38 | 58 | −0.38 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 11 | 45583 | 504 | 4.18 | 7 | −10.10 | −9.78 | −10.5 | 23 | 35 | 43 | −0.28 |

| 12 | 56452 | 378 | 5.02 | 6 | −10.80 | −10.65 | −11.30 | 13 | 37 | 25 | −0.33 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 13 | 60043 | 317 | 3.56 | 4 | −11.12 | −9.70 | −10.10 | 49 | 49 | 23 | −0.41 |

| 14 | 74702 | 549 | 5.95 | 2 | −11.00 | −11.12 | −9.80 | 21 | 17 | 27 | −0.24 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 15 | 81509 | 352 | 1.16 | 5 | −10.80 | −9.20 | −11.74 | 33 | 31 | 16 | −0.35 |

| 16 | 95090 | 582 | 2.02 | 5 | −9.85 | −8.69 | −1.46 | 13 | 12 | 64 | −0.19 |

| 17 | 95926 | 447 | 2.71 | 5 | −11.83 | −10.73 | −10.10 | 61 | 24 | 34 | −0.33 |

| 18 | 99671 | 401 | 1.06 | 4 | −10.64 | −9.30 | −10.10 | 60 | 34 | 12 | −0.34 |

| 19 | 105687 | 379 | 6.01 | 5 | −9.27 | −10.16 | −11.29 | 14 | 36 | 26 | −0.28 |

| 20 | 113491 | 470 | −1.43 | 4 | −12.07 | −10.30 | −10.00 | 74 | 34 | 21 | −0.31 |

| 21 | 116654 | 349 | 2.80 | 6 | −10.50 | −9.85 | −10.2 | 29 | 22 | 25 | −0.29 |

| 22 | 121855 | 435 | 1.10 | 5 | −10.50 | −9.40 | −8.19 | 50 | 29 | 60 | −0.30 |

| 23 | 121865 | 412 | 0.30 | 5 | −11.09 | −9.59 | −9.91 | 72 | 53 | 20 | −0.33 |

| 24 | 127917 | 299 | 0.56 | 5 | −9.71 | −9.45 | −10.96 | 48 | 32 | 29 | −0.40 |

| 25 | 128437 | 477 | 3.90 | 4 | −11.83 | −11.67 | −10.20 | 39 | 33 | 50 | −0.32 |

| 26 | 131547 | 476 | 4.19 | 6 | −11.41 | −9.43 | −10.10 | 16 | 16 | 22 | −0.27 |

| 27 | 134754 | 580 | 3.10 | 5 | −10.20 | −9.84 | −11.00 | 44 | 71 | 22 | −0.29 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 28 | 134755 | 580 | 3.10 | 5 | −10.80 | −9.20 | −9.87 | 41 | 24 | 7 | −0.31 |

| 29 | 163443 | 394 | 6.26 | 5 | −11.41 | −9.51 | −10.10 | 28 | 17 | 13 | −0.32 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 30 | 205511 | 335 | 3.49 | 6 | −9.91 | −10.75 | −10.62 | 31 | 54 | 24 | −0.33 |

| 31 | 282027 | 320 | 2.00 | 5 | −11.01 | −9.66 | −10.20 | 29 | 36 | 21 | −0.40 |

| 32 | 339601 | 415 | 2.62 | 5 | −10.75 | −8.97 | −9.56 | 23 | 12 | 26 | −0.35 |

| 33 | 371884 | 447 | 3.62 | 5 | −13.20 | −9.24 | −12.10 | 17 | 25 | 28 | −0.35 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 34 | 372046 | 493 | 6.89 | 5 | −11.70 | −10.70 | −12.48 | 50 | 58 | 20 | −0.22 |

| 35 | 372280 | 438 | 5.64 | 5 | −10.90 | −11.77 | −9.86 | 54 | 16 | 36 | −0.28 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 36 | 372294 | 454 | 4.54 | 6 | −10.50 | −11.51 | −9.73 | 37 | 16 | 21 | −0.26 |

| 37 | 600067 | 324 | 1.16 | 5 | −11.78 | −10.60 | −11.84 | 77 | 78 | 40 | −0.42 |

| 38 | 659162 | 434 | 4.93 | 5 | −10.50 | −10.21 | −11.31 | 46 | 25 | 28 | −0.31 |

| 39 | 659390 | 417 | 2.80 | 5 | −8.72 | −9.77 | −9.62 | 28 | 42 | 18 | −0.30 |

RB, rotatable bond; MW, molecular weight. LE (ligand efficiency) = ΔG/HA; 39 compounds from the National Cancer Institute diversity set that match all α-cobratoxin templates (1YI5, 1CTX, and 2CTX). Nineteen compounds are in bold, and 4 hits are shaded.

Subsequently, 4 hits from the binding assay (see below) were docked with the AutoDock Version 4.1 program from the Scripps Research Institute.26 The parameters were the same as AutoDock Version 3.0.5 but run on a 64-bit 576 processor LINUX cluster at the Scripps Research Institute. Four hits also docked with AChBP from 1YI5, and the dimensions of the grid were 90 × 80 × 80, with a spacing of 0.375 Å between the grid points. The grid box was centered on the coordinates 112.282 × 166.66 × 66.403. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Binding Energy and Kd of 4 Hits for AChBPs

| Ebinding, kcal/mol |

Kd, nM |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSC Number | Cbtx | AChBP | AChBP | [3H]Epibatidine | [125I]α-Bungarotoxin |

| 36387 | −7.74 | −9.68 | Ls | 20.49 | 13.83 |

| Ac | 78.96 | 241.70 | |||

| Bt | 37.45 | ||||

| 42258 | −6.87 | −10.59 | Ls | 245.70 | 93.43 |

| Ac | 1147.00 | 2913.00 | |||

| Bt | 1890.00 | ||||

| 121865 | −6.10 | −7.97 | Ls | 111.50 | 75.90 |

| Ac | 16.26 | 36.63 | |||

| Bt | 415.30 | ||||

| 134754 | −6.97 | −9.44 | Ls | 792.60 | 404.40 |

| Ac | 2366.00 | 4620.00 | |||

| Bt | 2629.00 | ||||

Ebinding from AutoDock Version 4.1. AChBP, acetylcholine binding protein; Kd, dissociation constant; Ac, Aplysia californica; Ls, Lymnaea stagnalis; Bt, Bolinus truncates.

Effect of hits on the binding of toxin

An adaptation of an SPA was employed to determine the apparent Kd value.27 AChBP (final concentration ~500 pM binding sites for Ls and Bt, ~1 nM binding sites for Ac), poly-vinyltoluene anti-mouse SPA scintillation beads (0.1 mg/ml), monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody from mouse, and [3H] epibatidine (5 nM final concentration for Ls and Bt, 20 nM for Ac) were combined in a phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0) with fixed concentrations of the competing ligands at 10 μM in a final volume of 100 μL. Total binding was determined in the absence of the competing ligand, and nonspecific binding was measured by adding a saturating concentration (15 μM) of the competitive ligand methyllycaconitine. The resulting mixtures were allowed to equilibrate at room temperature for a minimum of 2 h and measured on an LS 6500 liquid scintillation counter. The result was calculated by the fraction of [3H]epibatidine. The ligand with a fraction of [3H]epibatidine lower than 0.6 was selected for measuring its Kd values via [3H]epibatidine and [125I]α-bungarotoxin with increasing concentrations of the competing ligand in a final volume of 100 μL. The data obtained were normalized, fit to a sigmoidal dose-response curve (variable slope), and the Kd calculated from the observed EC50 value using GraphPad Prism Version 4.02 for Windows (San Diego, CA).

Effect of hits against α-cobratoxin

Male ICR mice weighing 20 to 30 g were used for the determination of lethality of the α-cobratoxin and the effect of selected ligand docking hits against α-cobratoxin (C6903 from Sigma). The Cbtx solutions, in 0.1 mL of sterile water, were prepared for 9 concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 0.14, 0.17, 0.18, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 mg/kg). Each concentration was injected intra-muscularly (IM) to the mice. Six mice were used for each test dose. The control group was injected with only vehicle. The number of deaths occurring within 24 h was recorded and the LD50 calculated from the plot between the concentration of venom and percent death. In the protocol using ligand hits as the protecting agent, the solutions of 3 hits, in 0.05 mL of 0.3% Tween-80, were prepared for 3 concentrations (1, 5, and 10 mg/ kg). Each concentration was injected into the mice intravenously (IV) at the tail vein. The control group was injected with only the vehicle, 0.3% Tween-80. After 30 min, 3LD50 of Cbtx in 0.1 mL of sterile water was injected (IM) into the mice. In the protocol using hits as antitoxin treatment, α-cobratoxin was injected (IM) before the injection of hits (IV) at the 5-mg/kg dose. The number of deaths occurring within 24 h was recorded. The results were expressed as the mean ± SEM of the number of animals used. Statistical comparisons were done using Student’s unpaired t test, with a p value <0.05 indicating significance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Virtual screening and docking results

Molecular docking was carried out to investigate the docking energy and binding mode of compounds to Cbtx using AutoDock program Version 3.0.5.23 Three bound Cbtx structures, 2 NMR structures (1LXG and 1LXH), and 1 crystal structure of a Cbtx-AChBP complex (1YI5) were available. The amino acid sequences of Cbtx and the binding site from the NMR structure12 (1LXG and 1LXH) were the same as in the crystal structure (1YI5) but different in shape. The structures from NMR were short and fat, whereas the structure from the crystal was long and thin. The binding poses of both Cbtx and AChR in the NMR structure were considered dissimilar from the crystal structure. When comparing the poses of both the Cbtx and AChR unit between the NMR structure and crystal structure, the difference in the Cbtx binding poses (RMSD = 5.251 Å) was found to be more than that of AChR (RMSD = 2.665 Å). This resulted from the differences in the environment and the state of Cbtx (solution vs. solid crystal), as well as the difference in the AChR unit between both structures. The bound AChR units in NMR (1LXG and 1LXH) were only the 15-mer peptide from the alpha-1 subunit of AChR (residues 181-198), whereas the AChBP in crystal was composed of 5 subunits and Cbtx bound at the alpha-7 subunit.

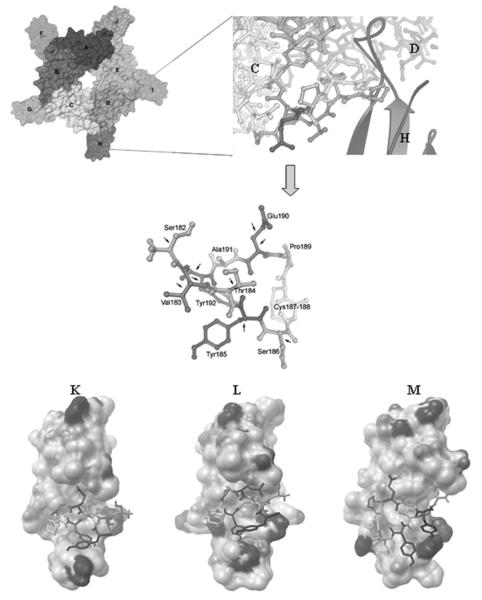

The Cbtx from the Cbtx-AChBP complex (1YI5) is more relevant as the binding mode is from the contribution of all 5 subunits in AchR, and therefore it was selected to prepare the Cbtx template. Among 3 reported crystal structures13,19,20 of the Cbtx from the Naja naja siamensis, 1CTX19 and 2CTX20 were unbound Cbtx crystals, and 1YI513 was a crystal structure of Cbtx bound to the pentameric AChBP. In the unbound Cbtx crystal structure, there were 71 ordered residues seen in the electron density, whereas the bound Cbtx crystal structure showed only 68 residues. These residues at the tip of Cbtx loop III did not contribute to interactions between Cbtx and the AChBP molecule, with their closest distance being 8 Å. Bourne et al.13 state that this 67-71 stretch and residues within loop III weakly contribute to Cbtx binding. In this study, the cobratoxin structures from 1YI5, 1CTX, and 2CTX were used as templates for virtual screening, and the 1YI5 bound region on chain C was used to validate the template of Cbtx as it is the only crystal structure of the complex between Cbtx (chain F-J) and AChBP (chain A-E). Chain H from the crystal structure was selected as the representative Cbtx because it was the most complete among the 5 Cbtx chains in the crystal structure. The Arg68 side chain of chain H was missing in the crystal structure. SwissPDBViewer was used to reconstruct the missing atoms in the side chain in a reasonable conformation. The rebuilt Arg68 side chain conformation was the same as in the 1CTX and 2CTX structures. Ser182-Tyr192 of chain C was selected to be the positive control to validate the Cbtx binding site for docking because it is a contiguous peptide near the acetylcholine binding site. Nine side chain rotatable bonds in the peptide were allowed to rotate in the redocking to validate the prepared α-cobratoxin active binding sites (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

1YI5 from the Protein Data Bank, α-cobratoxin (chain F-J) and acetylcholine receptor (chain A-E). Eleven residues from chain C (Ser182-Tyr192). The arrows show the 9 rotatable bonds used. The docking results are shown between 11 residues and α-cobratoxin, 1YI5 (K), 2CTX (L), and 1CTX (M).

The result shows that 100% of the docked conformations grouped into a single cluster using an RMSD clustering tolerance of 2.0 Å, and the docked orientation is close to that of the crystal structure with an RMSD of 1.1020 Å. The redocking result indicated that the prepared Cbtx protein is a good model for docking studies of the NCI diversity set of 1900 compounds. The docking result between the control peptide in 1YI5 was almost the same as 2CTX (RMSD = 0.311 Å) but a little different in 1CTX (RMSD = 0.617 Å), but they were both located in the binding site (Fig. 2). For virtual screening, after each of 100 docking runs per compound, the conformations that had the lowest docked energy of binding to each Cbtx (1YI5, 1CTX, and 2CTX) were clustered and ranked. Each cluster consisted of conformers that had similar 3D structures (RMSD < 2 Å). The top 175 compounds of each Cbtx with the energy cutoff at −8.72 kcal/mol were ranked. The lowest docking energies for 1YI5, 1CTX, and 2CTX were −13.86, −13.59, and −12.74, respectively, and the highest docking energies were −10.11, −10.12, and −9.52 for 1YI5, 1CTX, and 2CTX, respectively. Seventy-seven compounds matched the 3 Cbtx, but only 19 compounds with the lowest docking energy had a ligand efficiency of less than −0.30, adhering to Lipinski’s rule of 5. For experimental testing, 20 additional compounds were included in the in vitro evaluation based on their good pharmacodynamic properties (low docking energy and high percent membership in the largest cluster). The total number of compounds in the binding study was 39 (Table 1). Although these hit compounds violated Lipinski’s rule-of-5 criteria for pharmacokinetic purposes, these compounds could be modified later in terms of formulation and delivery system. The pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic consideration should be well balanced to increase the success rate. For instance, the 2 leads (NCI36387 and NCI134754) with good pharmacodynamic properties (binding energy < −11 kcal/mol) would have been missed upon the violation of Lipinski’s rule-of-5.

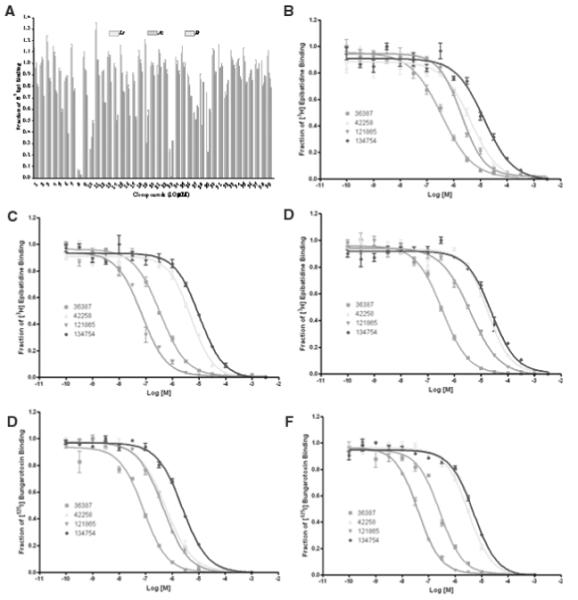

Effect of hits on the binding of toxin

Thirty-nine compounds from virtual screening were further investigated for their binding capability. The radioligand competition assay was adapted to determine whether the hits interfered with the binding of toxin to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Prior to the binding analysis, 10 μM of each compound was screened for its ability to compete or interfere with the binding of [3H]epibatidine to the 3 AChBPs (Ls, Ac, and Bt), as measured by a scintillation proximity assay (Fig. 3). Four hits (compounds 8, 10, 23, and 27) showed significant interference for the binding of [3H]epibatidine to the binding proteins. These potential hits and their Kd values were measured by competing with [3H]epibatidine and [125I]α-bungarotoxin (Fig. 3). Their chemical structures, NSC numbers, molecular weights, LE, binding energies, and Kd values are listed in Tables 2 and 3. A measured fraction greater than 1.0 is possibly due to a variation in number of AChBP molecules binding to the beads.

FIG. 3.

Screening test for the ability to displace the binding of (B-D) [3H]epibatidine and (E, F) [125I]α-bungarotoxin on (B, E) Lymnaea stagnalis (Ls), (C, F) Aplysia californica (Ac), and (D) Bulinus truncatus (Bt). The quick screen (A) with 4 hits; NSC36387, NSC42258, NSC121865, and NSC134754 are compounds 8, 10, 23, and 27, respectively. X-axis is the log concentration of the 4 hits in molar, the concentration of [3H] epibatidine was 5 nM for Ls and Bt and 20 nM for Ac, and [125I]α-bungarotoxin was 5 nM for Ls and 20 nM for Ac.

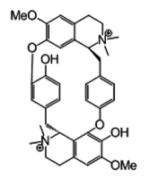

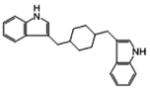

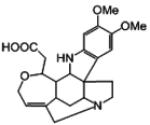

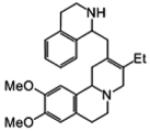

Table 3.

NCI Diversity Set Identified from Virtual Screening

| Chemical Structure | NSC Number | MW, Da | RB | Cluster (% Lowest Energy Clustering) | EdocUng, kcal/mol | LE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

36387 | 696 | 4 | 4 (16) | −11.10 | −0.20 |

|

42258 | 417 | 4 | 1 (65) | −11.23 | −0.38 |

|

121865 | 412 | 5 | 1 (72) | −11.09 | −0.33 |

|

134754 | 580 | 5 | 7 (44) | −10.20 | −0.29 |

RB, rotatable bond; MW, molecular weight. LE (ligand efficiency) = ΔG/HA.

In the assay, the 4 hits competitively displaced the antagonist ([125I]α-bungarotoxin) and the agonist ([3H]epibatidine) from their mutually exclusive binding sites on Lymnaea, Aplysia, and Bulinus AChBPs, with the concentrations from micromolar to nanomolar (Fig. 3 and Table 3). The compound that binds more strongly to the binding proteins has a lower Kd value. On [3H]epibatidine, NSC36387 (compound 8) was the most potent for binding with Ls and Bt, whereas NSC121865 (compound 23) was most potent in binding with Ac. On [125I] α-bungarotoxin, NSC36387 was the most potent in binding with Ls, whereas NSC121865 was most potent in binding with Ac. Furthermore, NSC36387, d-tubocurarine, is a well-known neuromuscular blocker and the active ingredient in curare. It is a plant-based alkaloid isolated from Chondodenron tomentosum. The results showed, by the graph shifting to the left (Fig. 3), that the activity for interfering with [3H]epibatidine and [125I]α-bungarotoxin for NSC121865 was better than NSC42258 (compound 10) and NSC134754 (compound 27), respectively. AutoDock4.1 results showed that 4 hits docked with AChBP better than Cbtx. NSC121865 was the most potent lead compound, with its mechanism of action either being competition or interference of the toxin’s ability to bind to the acetylcholine receptor.

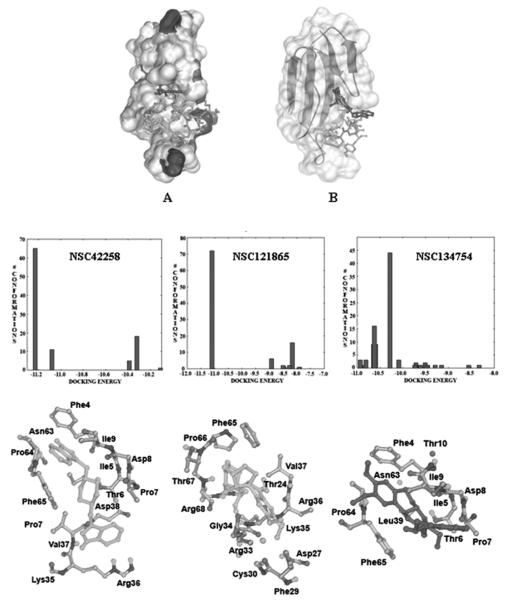

Compounds NSC42258 and NSC121865 are more drug like because each has a molecular weight less than 500, log P less than 5, and less than 5 rotatable bonds (i.e., they each obey Lipinski’s rules). LE24 is calculated by using binding free energy (ΔG) and number of heavy atoms (HA), LE = ΔG/HA. Compound NSC42258 had 65% clustering in the lowest energy dockings with a good LE value of −0.38. Compound NSC121865 had 72% clustering in the lowest energy dockings, with a good LE value of −0.33. The dockings of the 3 hits clustered by similarity of 3D structures (RMSD < 2 Å) and their interactions with amino acid residues of Cbtx are shown in Figure 4. The active binding site of Cbtx is occupied between loop I and II in the presence of the hits, and consequently, the Cbtx cannot bind to the acetylcholine receptor.

FIG. 4.

(A, B) The docked orientations of NSC42258 (turquoise/light gray), NSC121865 (light green /off white), NSC134754 (purple /black), and control peptide (purple /dark gray). The clusters of docked hits in the same 3D structure (RMSD of 2 Å), docking energy (kcal/mol), and the amino acid residues of α-cobratoxin interaction with the 3 hits are shown.

Effect of hits against α-cobratoxin

An in vivo test was carried out to investigate the effect of the 3 compound hits against Cbtx. The LD50 of Cbtx was determined. Cbtx is very potent, with an LD50 of 0.175 mg/kg (IM). The dose of Cbtx used in the experiment was 3LD50 instead of 4LD50 because Cbtx has a narrow therapeutic window. The toxic doses of the 3 hits were not determined due to their limited available quantity. However, the acute toxicity test of the 3 hits was conducted, and all mice survived after 24 h at the 10-mg/kg dose (IV bolus). All mice were observed for 1 more week and found to be normal. When the hit compounds were injected (IV) 30 min before Cbtx (3LD50) (IM), the survival time was prolonged significantly. The results show that all hits can prolong the survival time of the mice (Table 4). The hits at 10 mg/kg could not prolong the survival time of the mice more than the hits at 5 mg/kg (data not shown). Dixon’s Q test was used to discard the outliers from the data.28 The Qexp values of the highest numbers (> 24 h and 111 min) at 5 mg/kg (NSC42298 and NSC121865) were higher than Qcrit (95% confidence level [CL]). Therefore, these 2 numbers were discarded as outliers. For antitoxin activity, the hits at 5 mg/kg could protect the mice from the Cbtx when they were injected after the Cbtx (Table 4). The survival time was 45.2 ± 5.2 and 53.7 ± 15.6 min for NSC121865 and NSC134754, respectively. The survival time between NSC121865 and NSC134754 was not significantly different. Three hits could prolong the survival time of the mice if injected 30 min before injection with Cbtx. Two hits (NSC121865 and NSC134754) prolonged the survival time of the mice when Cbtx was injected before injection of hits. NSC121865 is the most promising candidate as it has both protection activity and antitoxin activity. This experiment supported the in vitro and in silico results.

Table 4.

Protective Effect and Antitoxin of the 3 Hits against α-Cobratoxin-Treated Mice

| Group | Dose, mg/kg, IV |

Survival Time, min | Average, Mean ± SEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protectiona | |||

| Control | 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 | 28.2 ± 1.0 | |

| 42258 | 5 | 37, 44, 50, 58, 59, >24 hb | 49.6 ± 4.2c |

| 1 | 35, 37, 39, 45, 49, 50 | 42.5 ± 2.6c | |

| 121865 | 5 | 44, 47, 52, 54, 56, 111b | 50.6 ± 2.2c |

| 1 | 35, 36, 38, 51, 52, 54 | 44.3 ± 3.6c | |

| 134754 | 5 | 31, 37, 47, 48, 51, 53 | 44.5 ± 3.5c |

| 1 | 40, 40, 42, 44, 53, 60 | 46.5 ± 3.3c | |

| Antitoxind | |||

| Control | 28, 31, 37, 38, 42, 45 | 36.8 ± 2.6 | |

| 42258 | 5 | 34, 34, 36, 42, 46, 56 | 41.3 ± 3.5 |

| 121865 | 5 | 38, 41, 44, 48, 48, 52 | 45.2 ± 2.1c |

| 134754 | 5 | 40, 41, 45, 55, 60, 81 | 53.7 ± 6.3c |

Hits were injected (intravenously [IV]) 30 min before injection of Cbtx (3LD50, intramuscularly [IM]), n = 6.

The outliers (Dixon’s Q test).

p < 0.05.

Hits were injected (IV) immediately after injection of Cbtx (3LD50, IM), n = 6.

CONCLUSIONS

Virtual screening is increasingly gaining acceptance in the pharmaceutical industry as a cost-effective and timely strategy for analyzing very large chemical data sets for potential interactions with therapeutic targets. Although the number of therapeutic targets that have been fully characterized by crystallography is currently limited, this situation is changing significantly as structural genomics initiatives begin to yield fruit. Accordingly, the work involved to validate all these potential targets, to demonstrate their therapeutic relevance, and to find effective ligands will become more dependent on the new high-throughput screening technologies. Molecular docking was used to investigate the binding of more than 1990 compounds to α-cobratoxin. This procedure is computationally intensive for analyzing a large database but provides the most detailed basis for determining which compounds are likely to be potent ligands. NSC121865 showed good competitive activity in interfering with the binding of [3H]epibatidine or [125I]α-bungarotoxin to the 3 AChBPs. Three hits (NSC42258, NSC121865, and NSC134754) have been shown to prolong the survival time of the mice if injected 30 min prior to injection with Cbtx, and 2 of these, NSC121865 and NSC134754, have been shown to prolong the survival time if injected immediately after injection with Cbtx. The mechanism of action is either a competition with or interference of the toxin’s ability to bind to the acetylcholine receptor caused by the compound binding to either the binding protein or the Cbtx. In clinical applications, NSC121865 (compound 23) would be a very useful potential lead in the development of a new treatment for snakebite victims.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank William “Lindy” Lindstrom, Garrett M. Morris, and Rodney Harris for valuable suggestions and discussions. This work was funded by the Office of the Higher Education Commission, Royal Golden Jubilee Project, Thailand Research Fund, Mahidol University Research fund. Computer modeling resources were provided by the Molecular Graphics Laboratory at the Scripps Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raweerith R, Ratanabanangkoon K. Immunochemical and biochemical comparisons of equine monovalent and polyvalent snake venoms. Toxicon. 2005;45:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong LV, Khoo HE, Quyen LK, Gopalakrishnakone P. Optimal immunoassay for snake venom detection. Biosensors Bioelectron. 2004;19:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernheim A, Lorenzetti E, Licht A, Markwalder K, Schneemann M. Three cases of severe neurotoxicity after cobra bite (Naja kaouthia) Swiss Med Wkly. 2001;131:227–228. doi: 10.4414/smw.2001.09731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chanhome L, Wongtongkam N, Khow O, Pakmanee N, Omari-Satoh T, Sitprija V. Genus specific neutralization of Bungarus snake venoms by Thai red cross banded krait antivenom. J Nat Toxins. 1999;8:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byeon W, Weisblum B. Affinity adsorbent based on combinatorial phage display peptides that bind α-cobratoxin. J Chromatogr B. 2004;805:361–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogay Y, Rzhevsky DI, Murashev AN, Tsetlin VI, Utkin YN. Weak neurotoxin from Naja kaouthia cobra venom affects haemodynamic regulation by acting on acetylcholine receptors. Toxicon. 2005;45:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doley R, King GF, Mukherjee AK. Differential hydrolysis of erythrocyte and mitochondrial membrane phospholipids by two phospholipase A2 isoenzymes (NK-PLA2-I and NK-PLA2-II) from the venom of the Indian monocled cobra Naja kaouthia. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;425:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walkinshaw MD, Saenger W, Maelicke A. Three-dimensional structure of the “long” neurotoxin from cobra venom. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2400–2404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.TseTlin V. Snake venom α-neurotoxins and other ‘three-finger’ proteins. Eur J Biochem. 1999;264:281–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Klaassen RV, Schuurmans M, van Der Oost J, Smith AB, et al. Crystal structure of an Ach-binding protein reveals the ligand binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411:269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smit B, Syed NI, Schaap D, van Minnen J, Kits KS, Lodder H, et al. Acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP), a novel glia-derived acetylcholine-receptor-like modulator of cholinergic synaptic transmission. Nature. 2001;411:261–268. doi: 10.1038/35077000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng H, Hawrot E. NMR-based binding screen and structural analysis of the complex formed between α-cobratoxin and an 18-mer cognate peptide derived from the α1 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor from Torpedo californica. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37439–37445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourne Y, Talley TT, Hansen SB, Taylor P, Marchot P. Crystal structure of a Cbtx-AChBP complex reveals essential interactions between snake alpha-neurotoxin and nicotinic receptors. EMBO J. 2005;24:1512–1522. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atassi MZ. Handbook of Natural Toxins. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celie PH, Klassen RV, van Rossum-Fikkert SE, van Elk R, van Nierop P, Smith AB, et al. Crystal structure of acetylcholine-binding protein from Bolinus truncatus reveals the conserved structural scaffold and sites of variation in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26457–26466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen SB, Talley TT, Radic Z, Taylor P. Structural and ligand recognition characteristics of an acetylcholine-binding protein from Aplysia californica. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24197–24202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402452200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waszkowycz B, Perkins TDJ, Sykes RA, Li J. Large-scale virtual screening for discovering leads in the postgenomic era. IBM Systems J. 2001;40:360–376. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Protein Data Bank . A Resource for Studying Macromolecules. http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walkinshaw MD, Saenger W, Maelicke A. Three-dimensional structure of the long neurotoxin from cobra venom. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2400–2404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betzel C, Lange G, Pal GP, Wilson KS, Maelicke A, Saenger W. The refined crystal structure of α-cobratoxin from N.n. siamensis at 2.4-Ao resolution. J Bio Chem. 1991;266:21530–21536. doi: 10.2210/pdb2ctx/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Repositories . First Diversity Set Information. http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/dscb/diversity_explanation.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasteiger J, Marsili M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electro-negativity: a rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:3219–3228. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Haliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, et al. Automated docking using a Larmarckian genetic algorithm and empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopkins AL, Groom CR, Alex A. Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:430–431. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Doodsell DS, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009 Apr 27; doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hibbs RE, Talley TT, Taylor P. Acrylodan-conjugated cysteine side chains reveal conformational state and ligand site locations of the acetylcholine-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28483–28491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dixon’s Q-Test . Detection of a Single Outlier. http://www.chem.uoa.gr/applets/AppletQtest/Text_Qtest2.htm. [Google Scholar]