Abstract

Aurora kinase A (AURKA), which is a centrosome-localized serine/threonine kinase crucial for cell cycle control, is critically involved in centrosome maturation and spindle assembly in somatic cells. Active T288 phosphorylated AURKA localizes to the centrosome in the late G2 and also spreads to the minus ends of mitotic spindle microtubules. AURKA activates centrosomal CDC25B and recruits cyclin B1 to centrosomes. We report here functions for AURKA in meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes, which is a model system to study the G2 to M transition. Whereas AURKA is present throughout the entire GV-stage oocyte with a clear accumulation on microtubule organizing centers (MTOC), active AURKA becomes entirely localized to MTOCs shortly before germinal vesicle breakdown. In contrast to somatic cells in which active AURKA is present at the centrosomes and minus ends of microtubules, active AURKA is mainly located on MTOCs at metaphase I (MI) in oocytes. Inhibitor studies using Roscovitine (CDK1 inhibitor), LY-294002 (PI3K inhibitor) and SH-6 (PKB inhibitor) reveal that activation of AURKA localized on MTOCs is independent on PI3K-PKB and CDK1 signaling pathways and MOTC amplification is observed in roscovitine- and SH-6-treated oocytes that fail to undergo nuclear envelope breakdown. Moreover, microinjection of Aurka mRNA into GV-stage oocytes cultured in 3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthine (IBMX)-containing medium to prevent maturation also results in MOTC amplification in the absence of CDK1 activation. Overexpression of AURKA also leads to formation of an abnormal MI spindle, whereas RNAi-mediated reduction of AURKA interferes with resumption of meiosis and spindle assembly. Results of these experiments indicate that AURKA is a critical MTOC-associated component involved in resumption of meiosis, MTOC multiplication, proper spindle formation and the metaphase I-metaphase II transition.

Keywords: aurora-A, MTOC, CDK1, PKB, meiotic maturation, mouse oocytes, spindle formation

Introduction

Aurora kinases, which form a serine/threonine protein kinase family that is conserved from yeast to human, play a crucial role in cell cycle regulation. The vertebrate Aurora family is composed of three members: Aurora-A (AURKA), Aurora-B (AURKB) and Aurora-C (AURKC),1 each of which exhibits a distinct sub-cellular localization and function during the cell cycle.2,3 AURKA was first isolated as a breast tumor amplified kinase,4 is frequently overexpressed in human cancers,3,5 and has been identified as a candidate low penetrance cancer-susceptibility gene.6,7 Tissue specific overexpression induces hyperpaslia in mouse mammary epithelium8 and transforms mammalian fibroblasts, giving rise to aneuploid cells that contain multiple centrosomes and multipolar spindles.9 The resulting genetic instability likely contributes to tumorigenesis.10 Aurka expression as well as AURKA protein accumulation is coupled with cell cycle progression, peaking at the G2/M transition; upon mitotic exit, AURKA protein is degraded by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C).11–13

Threonine phosphorylation in the activation loop (T288 in human AURKA13) is required for AURKA activation.14,15 Centrosomal AURKA activation largely depends on the LIM-domain protein Ajuba16 and p21-activated protein kinase (Pak1)17 but is CDK-independent.16 PAK1 re-localizes to the centrosome during the mitotic phase of the cell cycle where it phosphorylates AURKA at T288 and S342, two sites that are important for AURKA activation. In addition, inhibiting PAK1 delays centrosome maturation.17 Later in mitosis, AURKA activation occurs on microtubules (MT) and involves RAN-GTP that in turn promotes TPX2 association with AURKA, which is essential for both AURKA associating MTs and activation.18–20 Targeting Aurka mRNA with siRNAs indicates that AURKA is required for mitotic entry, centrosome maturation and mitotic spindle assembly.16,21,22

AURKA also regulates the meiotic cell cycle. Both progesterone and insulin-induced maturation of Xenopus oocytes stimulate CPEB-mediated translation of several maternal mRNAs (Mos and Ccnb) and maturation by alleviating GSK3-mediated inhibition of AURKA activity. For insulin, signaling involves PI3K that is essential for AURKA activation.23 In addition, microinjection of a constitutively active membrane-bound form of AURKA (Myr-Aurka) mRNA mobilizes Mos mRNA and activates MPF (a complex of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) and cyclin B24–26), but the oocytes arrest at MI.27 In mouse oocytes, microinjection of an AURKA antibody decreases the rate of GVBD and produces a distorted MI spindle organization.28

In most mammalian species, the meiotic cell cycle is arrested at prophase I in females. Meiotic maturation is characterized by germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) and two successive M phases that occur without an intermediate S phase to produce a haploid gamete. Of note is that meiotic spindle assembly in oocytes occurs in the absence of centrioles.29 Acentrosomal spindle assembly is accomplished by the spontaneous nucleation of MTs around the condensed chromosomes, and by spindle organization in the presence of multiple microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs) that functionally replace centrosomes.30,31 As in the mitotic cell cycle, MPF is a master regulator of oocyte maturation.

A maturation-associated decrease in cAMP, which is likely mediated by phosphodiesterase 3A (PDE3A),32 is essential for resumption of meiosis.33 Protein kinase PKB/Akt is responsible for PDE3A activation.34 PKB is also important for CDK1 activation and is involved in resumption of meiosis.35 cAMP-mediated GV arrest is regulated by PKA, which catalyzes an activating phosphorylation of WEE1B36 and an inhibitory phosphorylation of CDC25,37 in Xenopus oocytes. PKA probably mediates phosphorylation mouse CDC25B;26 cdc25b knock-out mice reveal that CDC25B is essential for CDK1 activation during resumption of meiosis in mouse oocytes.38

Because AURKA is involved both in mitotic entry and mitotic progression,2 we examined the role of AURKA in mouse oocyte maturation. We find that AURKA activation precedes GVBD and is independent of PI3K-PKB signaling pathway and CDK1 activity. AURKA becomes localized to MTOCs and the spindle. Overexpression of AURKA leads to formation of an abnormal MI spindle whereas RNAi-mediated reduction of AURKA interferes with resumption of meiosis and spindle assembly.

Results

AURKA associates with MTOCs and spindle during meiotic maturation

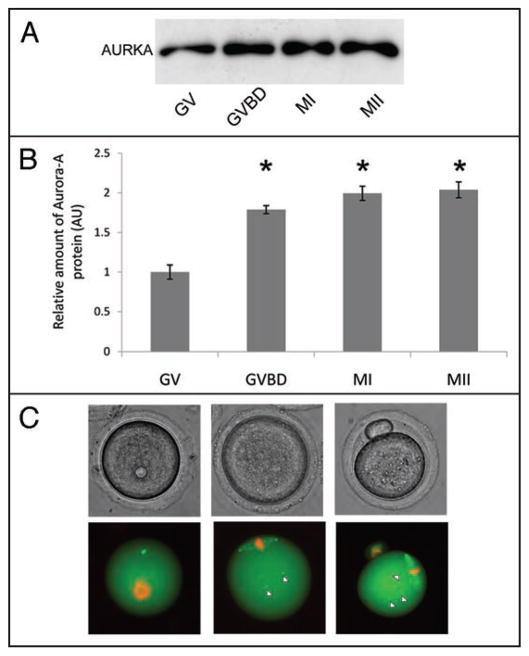

AURKA is present in mammalian oocytes.28,43,44 We first conducted immunoblotting experiments to assay AURKA during oocyte maturation; specificity of the antibody was confirmed using synchronized HeLa cells and NIH 3T3 fibroblast (Fig. S1). AURKA was present in immature (germinal vesicle, GV), maturing (germinal vesicle breakdown, GVBD; metaphase I, MI) and mature oocytes (metaphase II, MII). The amount of AURKA protein increased modestly between GV-and GVBD and then remained essentially constant between MI and MII (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Protein expression and subcellular localization of AURKA during meiotic maturation. (A) Immunoblot blot analysis of AURKA in cumulus-free oocytes (200 oocytes per lane) cultured in vitro to various stages—GV (0 h), GVBD (1 h), MI (7 h), MII (18 h). The amount of AURKA protein increased slightly around GVBD. (B) Quantification of immunoblots. The experiment was performed three times and the data are expressed as mean ±SEM. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) in comparison to GV-stage are marked (*) (C) Phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy images of oocytes after co-injection of Gfp-Aurka mRNA (2–5 pl of 200 ng/μl) and mCherry-H2B (2–5 pl of 25 ng/μl) into GV-stage. Total AURKA was mainly present at MTOC at GV-stage oocytes, at MI and MII AURKA was mainly associated with spindle with a clear concentration on the spindle poles and cytoplasmic MTOCs (arrowheads).

To visualize AURKA subcellular localization during maturation from GV to MII, oocytes were co-injected with Gfp-Aurka and mCherry-H2B mRNA (Fig. 1C). The fluorescent signal of GFP-AURKA was diffusely distributed in the oocyte with a clear accumulation on MTOCs in GV-stage oocytes (Figs. 1C and S2). As oocytes underwent GVBD and the number of MTOCs increaseed, GFP-AURKA was detected on all MTOCs (data not shown). At MI and MII, GFP-AURKA localized to the spindle and mainly to the spindle poles and cytoplasmic MTOCs (Fig. 1C). These results are similar to those reported in somatic cells where AURKA expression is cell cycle dependent, peaking at M-phase and is localized in cytoplasm, as well as on centrosomes and the spindle.45

Activation of AURKA precedes GVBD during the resumption of meiosis

In somatic cells, AURKA activity is regulated by phosphorylation on T288 and S342 where AURKA is localized to centrosomes and the minus ends of spindle MTs.16,19,20,42,45 Accordingly, we examined the spatio-temporal localization of active AURKA in oocytes using an antibody that is specific for AURKA phosphorylated on T288 (Fig. 2A).

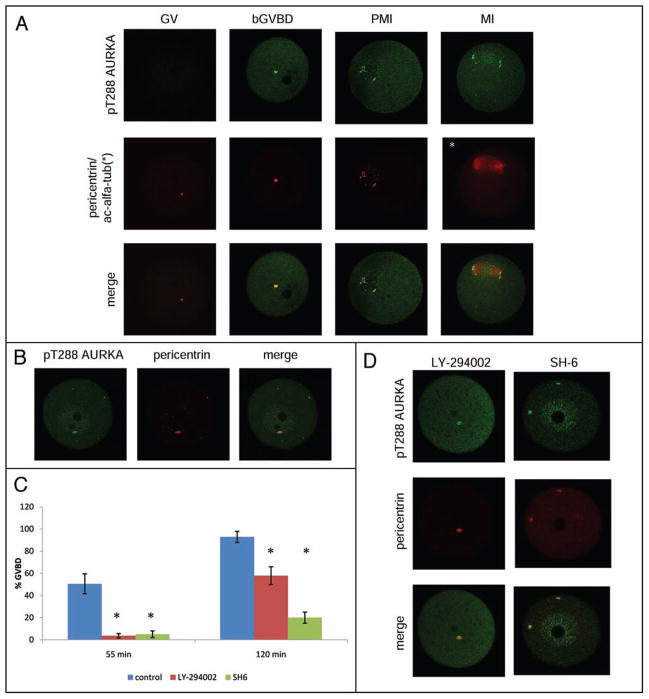

Figure 2.

PI3K-PKB and CDK1 independent AURKA activation precedes resumption of meiosis. Localization of pT288 AURKA (active form) during meiotic maturation (A). MTOC-associated AURKA is phosphorylated on T288 before GVBD (bGVBD), then during prometaphase I (PMI) and metaphase I (MI) pT288 AURKA remains associated with MTOCs. Green—pT288 AURKA, red—pericentrin (MTOCs). (B) Inhibition of CDK1 activity does not prevent activation of AURKA and multiplication of MTOCs. Oocytes, cultured for 90 min in the presence of Roscovitine, showed phosphorylation of AURKA on T288 at amplified MTOCs or within the nucleus. (C) Ability of LY-294002 or SH-6 oocytes to resume meiosis. The experiment was performed four times and around 200 oocytes were counted for each group. Error bars show confidence intervals. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) in comparison to control are marked (*) (D) PI3K-PKB signaling pathway is not involved in AURKA activation. Oocytes were cultured in medium supplemented with LY-294002 or SH-6 for 90 min and then GV-stage oocytes were used for imunofluorescence staining. Inhibition of PI3K or PKB did not block phosphorylation of AURKA, multiplication of MTOC and induced presence of pT288 AURKA within the nucleus.

MTOCs in GV-stage oocytes were completely negative for pT288 AURKA, but active pT288 AURKA was preferentially associated with MTOCs before GVBD and after GVBD (prometaphase I, PMI); this result is consistent with previous data in somatic cells.45 Later in meiosis active pT288 AURKA was almost completely located on the poles of the metaphase spindle in MI oocytes (Fig. 2A) and a weak but significant signal was detected in the area of aligned chromosomes. This localization contrasts to that in somatic cells in which a subpopulation of active pT288 AURKA is observed on the minus ends of spindle MTs.16,19,20,42,45 The localization of pT288 AURKA in the area of aligned chromosomes is consistent with AURKA-dependent phosphorylation of CENP-A.46 These results show that activation of AURKA precedes GVBD in mouse oocytes and occurs specifically on MTOCs, and that its activity at later stages of maturation is essentially restricted mainly to MTOCs.

Activation of AURKA is independent of PI3K-PKB signaling pathway and CDK activity

To explore if any causal relationship exists between AURKA and CDK activation, we analyzed AURKA activation in oocytes in which CDK activity was inhibited by Roscovitine. As anticipated, oocytes did not resume meiosis in the presence of Roscovitine (data not shown). In these oocytes, which contained an intact nuclear membrane, active AURKA was observed in the nucleus and co-localized with 1 or 2 MTOCs (time 55 min, Fig. S3) or alternatively, active AURKA was associated with multiple MTOCs (time 90 min, Fig. 2B). Based on the data in Figures 2A, B and S3 we conclude that activation of AURKA precedes GVBD and it is independent of CDK1 activity.

We previously reported that protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) is involved in CDK1 activation and GVBD in mouse oocytes.35 Full activation of PKB during GVBD is independent of CDK1 activity and requires phosphorylation of T308 and S473 residues shortly before GVBD.35 In Xenopus oocytes, PI3K acts upstream from AURKA during insulin stimulated maturation.23 To assess whether AURKA activity requires the PI3K-PKB signaling pathway, we first determined the time course of phosphorylation of AURKA on T288 and PKB on S473 and T308 prior to GVBD (Fig. S4). Double-staining of pT288 AURKA and pS473 or pT308 PKB indicated that phosphorylation of AURKA and phosphorylation of PKB on S473 on the MTOC occurs within 20 min, whereas PKB phosphorylation on T308 on the MTOC was observed later (by 40 min). Thus, AURKA activation precedes full activation of PKB.

AURKA activation also appears independent of the PI3K-PKB signaling pathway. AURKA activation was assayed in oocytes cultured in medium containing a LY-294002 (an inhibitor of PI3K) or SH-6 (an inhibitor of PKB). Resumption of meiosis was significantly inhibited at 55 min (control 50.5%; LY-294002 3.6%; SH-6 5%) and at 120 min (control 92.9%; LY-294002 57.9%; SH-6 20%) when oocytes were cultured in medium containing either inhibitor (Fig. 2C). Nevertheless, active AURKA was found on 1–3 MTOCs after both LY-294002 and SH-6 treatment and also in nucleus after SH-6 treatment (Fig. 2D and S5).

The fact that not only roscovitine treatment (CDK1 inhibition) but also SH-6 treatment (PKB inhibition) induced pT288 AURKA nuclear accumulation but LY-294002 treatment (PI3K inhibition) did not, probably reflects involvement of PI3K (but not downstream PKB) in pT288 AURKA nuclear accumulation. In summary, activation of MTOC-located AURKA is independent of PI3K-PKB and CDK1 signaling pathways.

Expression of exogenous AURKA induces MTOCs multiplication in the absence of CDK activity in GV-arrested oocytes

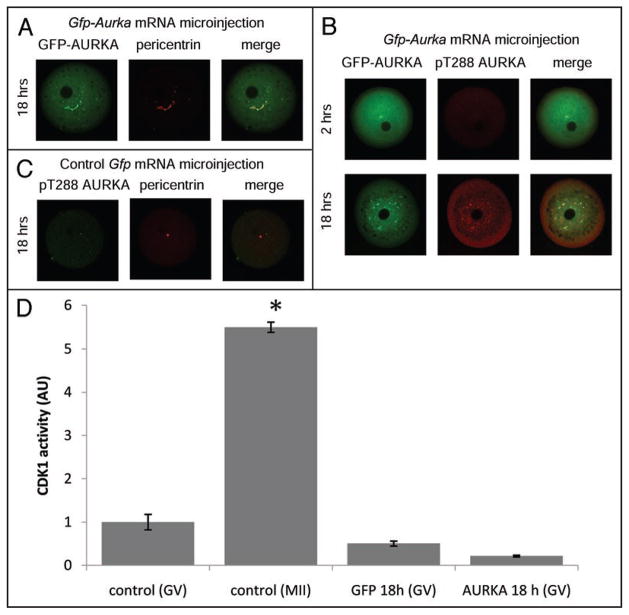

We were initially interested whether overexpression of AURKA in prophase I oocytes would accelerate GVBD or even overcome IBMX-mediated meiotic arrest. Microinjection of GFP-tagged Aurka mRNA (250 ng/ul) was used to overexpress the AURKA protein; a control group was injected with Egfp mRNA. Both groups of oocytes were cultured in the presence of IBMX for 18 h (Fig. 3A–C). A fluorescent signal for the GFP-AURKA protein was detected within 1.5–2 h after microinjection (Fig. 3B). Nevertheless, even 18 h following injection, the oocytes did not resume meiosis, i.e., the retained an intact GV (data not shown). Expression of AURKA, however, triggered amplification of MTOCs in the presence of intact GV (Fig. 3A and B) and in the absence of CDK1 activity (Fig. 3D). GFP-tagged AURKA was located on all MTOCs and initially was inactive 2 h following injection and culture in IBMX-containing medium but was activated by 18 h following injection (Fig. 3B). AURKA activation may be the consequence of AURKA-mediated autophosphorylation.42 These results suggest that although AURKA activation is not sufficient to induce maturation under conditions that maintain inhibitory levels of oocyte cAMP, AURKA activation initiates the process of multiplication of MTOCs independent of CDK1 activity.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of AURKA triggers MTOCs multiplication in GV-arrested oocytes. Gfp-Aurka. mRNA was microinjected into GV-blocked oocytes (2–5 pl of 250 ng/μl); Egfp mRNA was used as a control. (A) Exogenous AURKA caused multiplication of MTOCs in the presence of an intact GV after overnight incubation. GFP-AURKA was located on all MTOCs, (B) but 2 h after injection was non-phosphorylated. Overnight incubation led to phosphorylation of exogenous GFP-AURKA on T288. Pericentrin was used as a MTOC marker. (C) Endogenous AURKA is not phosphorylated during overnight culture in IBMX-containing medium (D) Activity of CDK1 (arbitrary units) was assayed on extracts from 10 oocytes per sample. The experiment was done 3 times and activity is expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical difference (p < 0.05) in comparisons to GV-stage control is marked (*).

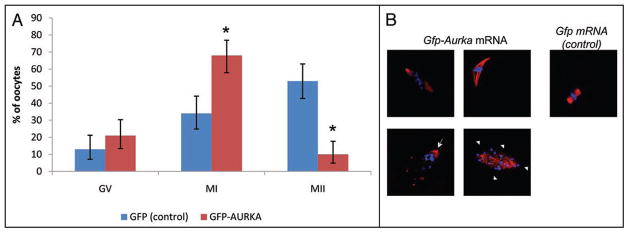

Overexpression and downregulation of AURKA perturbs meiotic progression

As documented above, overexpression of AURKA in the presence of high level of cAMP results in multiplication of MTOCs. We injected Gfp-Aurka mRNA in GV oocytes and after 2 h in the presence of IBMX inhibitor, the oocytes were transferred to IBMX-free culture medium to initiate resumption of meiosis and then cultured for 18 h, by which time control oocytes reached and were arrested at MII (Fig. 4). Overexpression of AURKA led to a significant reduction (p = 0.0000) in the percentage of oocytes extruding the first polar body (10% MII) in comparison to control EGFP overexpressing oocytes (53% MII) (Fig. 4A). This was due to the failure of the oocytes to complete the first meiotic division, as the percentage of oocytes remaining arrested at the GV stage was similar (p = 0.0921) in both AURKA and control EGFP groups (22%; control 13%). To determine how AURKA overexpression perturbed the first meiotic division, we used DAPI and acetylated α-tubulin antibody for immunostaining. In control oocytes injected with Egfp, a spindle of a normal size was initially formed after 7 h of culture in IBMX free medium. However, overexpression of AURKA resulted in distortion of MTs or formation of an unusually long spindle stretching from one side of the oocyte to the other (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

MI spindle defects induced by AURKA overexpression. (A) Aurka mRNA (2–5 pl, 350 ng/ul) injected oocytes, cultured for 18 h, were evaluated. Overexpression of AURKA blocks oocytes in PMI/MI. Altogether 100 GFP (control) and 99 GFP-AURKA oocytes were evaluated in three independent experiments. Error bars show confidence intervals. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) in individual cell cycle stages (MI and MII) are marked (*), difference in GV stage is not significant (B) Morphological defects such as formation of abnormally long spindle, absence of congression of tetrads or formation of unipolar (arrow) and multipolar spindles (arrowheads) were analyzed by immunocytochemistry. The 83 injected oocytes from three independent experiments were evaluated and morphologically analyzed. Red—acetylated α-tubulin, blue—DAPI.

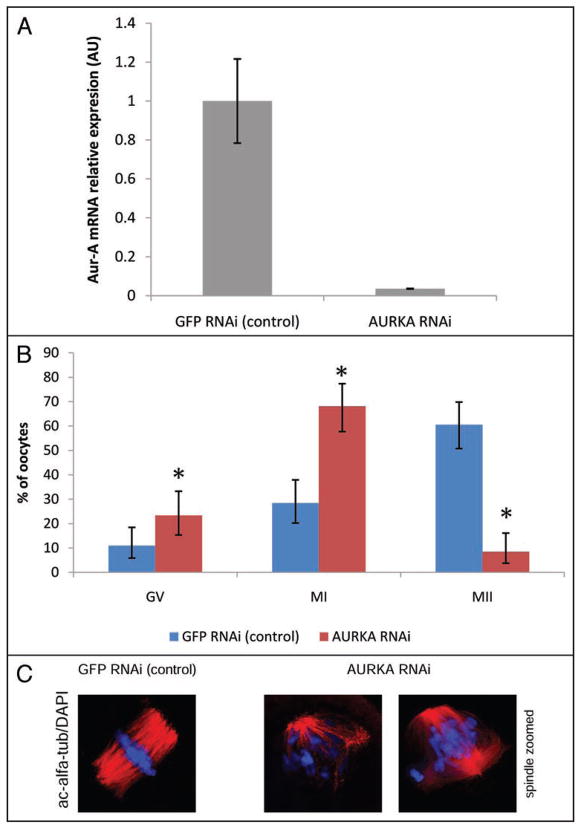

We used RNAi to assess loss-of-the function of AURKA during meiotic maturation. Long Aurka dsRNAs was injected into GV-intact oocytes. The oocytes were then cultured for 24 h in IBMX-supplemented culture medium to inhibit maturation and permit time for RNAi-mediated targeting of Aurka mRNA, which was assayed by real time qPCR. As expected, Aurka mRNA level was significantly decreased (Fig. 5A). The oocytes then transferred to IBMX-free medium and evaluated after 18 h in culture for resumption of meiosis and MII progression. We found that both resumption of meiosis and the ability to reach MII were inhibited (Fig. 5B). The differences between the control Egfp RNAi group and Aurka RNAi group in the ability to resume meiosis were significant (p = 0.0234; 11% GV at Egfp RNAi, 23% GV at Aurka RNAi). Moreover, the oocytes with depleted AURKA failed to reach MII (p = 0.0000; 9% MII at Aurka dsRNA, 61% MII at control Egfp dsRNA). In contrast to a normal MI spindle in control oocytes injected with Egfp dsRNA (Fig. 5C), the Aurka mRNA depleted oocytes had readily apparent spindle defects in MI that comprised problems with bipolar spindle formation and chromosomes alignment (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Downregulation of AURKA leads to incorrect spindle assembly and PMI/MI arrest. Oocytes injected with Aurka dsRNA or with Egfp dsRNA as a control were cultured for 24 h in IBMX-supplemented medium. (A) Aurka mRNA level in relative arbitrary units after RNAi mediated knockdown in GV-arrested oocytes. Total RNA was subsequently isolated and used for real-time PCR to quantify the level of Aurka mRNA. Egfp was used as an external standard. The decrease in the amount of Aurka mRNA was significant (p < 0.05). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. (B) Meiotic maturation of dsRNA injected oocytes. Oocytes after microinjection of Aurka dsRNA are arrested PMI/MI, when evaluated 18 h after IBMX release. 109 GFP RNAi and 94 AURKA RNAi oocytes were analyzed in three experiments. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) in individual cell cycle stages (GV, MI and MII) are marked (*) (C) Phenotypes of AURKA knockdown in mouse oocytes. Representative images of three experiments (approx. 100 oocytes) showing contol MI phase spindle of oocytes injected with Egfp (left) and oocytes injected with Aurka dsRNA (right) at the time 7 h after their transfer to IBMX-free medium. Red—acetylated α-tubulin, blue—DAPI for DNA staining.

Because we were unable to find an antibody that was suitable to measure total AURKA by immunocytochemistry (data not shown), the effectiveness of RNAi on the protein level was verified by microinjection of GV-arrested oocytes in the two steps: (1) injection of GFP-tagged AurkaA mRNA to allow development of a fluorescent signal and (2) then injection of Aurka dsRNA. In these oocytes, the fluorescent signal was significantly depleted after 24 h of culture in IBMX-containing medium, although a very weak MTOC-associated signal from the remaining GFP-AURKA could be detected (Fig. S6). These results strongly suggest that endogenous AURKA protein was markedly reduced by the RNAi approach.

Results of these experiments implicate AURKA in both in resumption of meiosis and in spindle assembly and that perturbing the normal amount of AURKA by either overexpression or RNAi-mediated downregulation leads to PMI/MI arrest.

Discussion

Consistent with previous reports documenting the presence of AURKA in mammalian oocytes (mouse, porcine and bovines28,43,44) we also detect by immunoblotting AURKA in mouse oocytes. Moreover, we find a modest maturation-associated increase in the amount of AURKA during GVBD; the amount of AURKA then remains essentially constant until MII. This finding contrasts with Yao et al., who reported that the amount of AURKA was higher in GV-intact oocytes and MII-arrested eggs than at intervening stages of maturation. This difference may be resolved by our finding that when we used the same antibody as that described in Yao et al., (a rabbit polyclonal from Cell Signaling Technology), the band detected had an electrophoretic mobility that didn’t correspond to that of AURKA. We confirmed the specificity of the mouse monoclonal antibody used in our studies (see Fig. S1); antibody specificity was not confirmed in the Yao et al., report.

Phosphorylation of T288 within the activation loop of AURKA is critical for AURKA activation.42 We find that only MTOC-located AURKA is phosphorylated on T288 and this phosphorylation precedes the activation of CDK1 and GVBD. At MI, active pT288 AURKA is observed mainly at spindle poles, in contrast to somatic cells, where active AURKA staining remains intense at the spindle poles and also minus-end of spindle MTs.16,19,20,45 Enrichment of centrosomes for active AURKA in somatic cells16,17,45,47 and MTOCs in oocytes (present results) support the current view that AURKA plays a key role in centrosome3,21 or MTOCs maturation.

We have previously shown that PKB activation associated with PKB phosphorylation on S473 and T308 precedes CDK1 activation and is involved in resumption of meiosis.35 In Xenopus oocytes, insulin stimulated AURKA activation during resumption of meiosis depends on PI3K.23 We report here that activation of AURKA precedes the full phosphorylation of MTOC-associated PKB on the two key residues, suggesting that AURKA activation is a very early event during resumption of meiosis. Moreover, results of our inhibitor studies indicate that AURKA activation is independent of both PI3K-PKB a CDK1 signaling.

Functional studies provide clues that AURKA is essential for MTOC maturation and resumption of meiosis. In contrast to Xenopus oocytes,27 our results show that overexpression of AURKA per se does not allow resumption of meiosis in the presence of high cAMP level (due to the presence of IBMX in the culture medium). This difference could be explained by a different Aurka constructs used the two studies. We used a wild-type AURKA, whereas study using Xenopus oocytes employed a constitutively active membrane bound myr-AURKA. The non-physiological localization of the membrane bound form of AURKA could serve as the basis for the observed differences. We noted that exogenously expressed AURKA is phosphorylated on T288 (a marker of activity) but still is not able to induce GVBD when oocytes are cultured in IBMX-containing medium. Interestingly, we observe multiplication of MTOCs in spite of presence of an intact GV and no increase in CDK1 activity. Although the mechanism of MTOC multiplication is still unknown, we have shown that the process is not associated with CDK1 activity but it may be triggered by AURKA activity in mouse oocytes. This finding is consistent with the effect of centrosome amplification caused by AURKA overexpression in mouse fibroblasts and several cancer cells.2,48,49

RNA-mediated reduction in AURKA reveals a role for AURKA in resumption of meiosis and defects in MI spindle formation, i.e., fewer oocytes resumed meiosis, and those that did, MI spindle defects were commonly found. The observation that a significant fraction of treated oocytes resumed meiosis likely reflects that the RNAi-mediated knockdown is incomplete and that the remaining active AURKA associated with the MTOCs is sufficient to support maturation, but not proper spindle formation. Oocyte-specific ablation of AURKA using transgenic models (e.g., transgenic RNAi or oocyte specific knock-out) could result in a more robust depletion of AURKA in oocytes and therefore define more precisely a role for AURKA in maturation.

Understanding how MTs reorganize during the cell cycle to assemble into a bipolar spindle is a classic problem of cell biology. Mitotic and meiotic spindles are highly dynamic structures, which assemble around chromosomes or sister chromatids and then distribute the chromosomes equally to each daughter cell. Therefore, it is essential that the centrosomes of the bipolar mitotic spindles generate astral MTs that continuously search for chromosomes.50

In mouse oocytes (as the model of acentrosomal spindle assembly) MTs nucleate around condensing chromosomes and the spindle self-organizes in the presence of multiple MTOCs.31,51 AURKA likely facilitates centrosome maturation in MT nucleation by recruiting and/or phosphorylating centrosomal components sequentially and thereby contributes to mitotic spindle assembly.3,21,52,53 RNAi-mediated reduction of AURKA strongly implicates an essential role for AURKA for formation of a normal spindle with properly aligned chromosomes. This finding is consistent with a similar function of AURKA in mitotic cells.21 On the other hand overexpressing AURKA produces mainly MI-arrested oocytes with extremely elongated spindles. A similar elongation of the metaphase I spindle was previously reported Dumon et al.,51 after expressing a constitutively active form of Ran-GTP (RanQ69L). Thus, AURKA and Ran-GTP may participate in the same pathway during meiosis and responsible for spindle elongation. Nevertheless, expression of RanQ69L does not compromise polar body extrusion and chromosome segregation, but increasing AURKA activity significantly induces MI arrest. Ongoing studies are examining whether upregulation of AURKA in mouse oocytes indirectly induces activation of spindle-assembly checkpoint (SAC) during MI or whether AURKA directly regulates SAC activity.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that AURKA plays multiple roles crucial for proper meiotic maturation in mouse oocytes. AURKA is involved in regulation of MTOCs multiplication/maturation, resumption of meiosis, spindle microtubule dynamics, and organization of the metaphase spindle. The signaling pathways in which AURKA is included and its real activators during meiotic maturation in mammalian oocytes will be the subject of future investigations.

Materials and Methods

Oocyte collection, culture and RNA microinjection

Mouse ovaries were obtained from 3–4 week-old PMSG-primed (C57BL/6J X BALB/c) F1 hybrid female mice. Ovaries were transferred to bicarbonate-free minimal essential medium (Earle salt; E7510, Sigma) supplemented with 3 mg/ml of polyvinylalcohol (PVA), 0.23 mM pyruvic acid and 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.3); the medium was at 37°C. Resumption of meiosis (GVBD) was inhibited by adding 0.1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methyl-xanthine (IBMX) to the isolation and culture media. Oocytes were cultured in M-16 medium (M7292, Sigma) at 37.5°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere.

For inhibitor studies, Roscovitine, as a specific CDK1 inhibitor, was used at 25 μM, the working concentration for LY-294002, a specific PI3K inhibitor, was 100 μM,35 and SH-6, a specific PKB inhibitor was used as 50 μM.39,40 Oocytes were first cultured in M16 containing the inhibitor and 100 μM IBMX for 1 h. The oocytes were then washed and transferred to IBMX-free medium containing the inhibitor and then cultured for different lengths of time as indicated in the figure legend.

Oocytes were microinjected with 2–5 pl of an RNA solution using a MIS-5000 micromanipulator (Burleigh, Exfo Life Sciences, USA) and PM 2000B4 microinjector (MicroData Instrument, USA). Oocytes were injected in Whitten’s medium supplemented with 15 mM Hepes (pH 7.3) and 0.1 mM IBMX. Pipettes for microinjection were made using p97 Pipette Puller (Sutter Instrument Company, USA).

In vitro mRNA and dsRNA production for microinjection

Full-length mouse Aurka cDNA was purchased from RZPD (GI:15928465, MGC:11471, IMAGE:3968835) in a pCMV-SPORT6 plasmid.

Polyadenylated and capped mRNA for microinjection was produced by in vitro transcription using mMESSAGE mMACHINE® T3 Kit (Ambion, #1348). To generate the template for transcription, full-length mouse Aurka cDNA was cloned into the SpeI site (for N-terminal GFP tags) of the pBluscript-GFP vector containing a T3-promoter and the Xenopus globin 5′UTR, 3′UTR and Kozak’s sequences for high mRNA stability and efficient translation initiation, respectively. This vector was obtained from Martin Anger, University of Oxford, UK, and will be described elsewhere. For in vitro transcription, the vectors were linearized with AscI. After in vitro transcription, mRNAs were immediately polyadenylated using the Poly(A) Tailing Kit (Ambion, #AM1350). mRNAs were purified using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, #74104). Egfp mRNA for control microinjection was transcribed from an empty pBluscript-GFP vector.

dsRNA was used to downregulate Aurka mRNA in mouse oocytes. The plasmid bought from RZPD was also used for amplification of DNA template for dsRNA synthesis using PCR strategy. Following primers were used for Aurka: AGGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACTGCCAGTGTTCCTCGAC, ACTCGAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACTGGTTGGCTCTTTGCTAGT; for control Egfp AGGATCCTAATACGACTAACTATAGGGAGAATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGA and ACTCGAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCGGCCGCTTTACTTGTACA. The length of dsRNA product was 952 bp for Aurka and 712 bp for Egfp.

Both mRNA and dsRNA, in nuclease free water (Ambion; #AM9939), were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until used for micro-injection.

Total RNA isolation and mRNA quantification

Total RNA from 15 or 25 oocytes was isolated using Absolutely RNA® Microprep Kit (Stratagene) and eluted with 42 μl of elution buffer. External Egfp mRNA (0.04 pg Egfp mRNA per oocyte) was added to lysed oocytes to serve as a control for quantifying RNA recovery and normalizing the RT-PCR data to the exogenously added Egfp mRNA. The eluted total RNA (3 μl) was used in a 10 μl reaction volume using one-step QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit Qiagen, #204243,). Aurka primers were purchased (QuantiTect Primer Assay QT00145950, Qiagen); Egfp primers were TTCAAGATCCGCCACAAC and GACTGGGTGCTCAGGTAG. One-step real-time RT-qPCR was done using a Chromo4 Real-Time PCR detection System (Biorad), and passive ROX reference was used for reaction volume correction. The following one-step real-time qRT-PCR protocols were used, Aurka: (1) 50°C 30 min, (2) 95°C 15 min, (3) 94°C 15 sec, (4) 55°C 30 sec, (5) 72°C 30 sec, (6) plate reading, (7) go to step 3 for 50 additional cycles; Egfp: (1) 50°C 30 min, (2) 95°C 15 min, (3) 94°C 15 sec, (4) 50°C 30 sec, (5) 72°C 30 sec, (6) plate reading, (7) go to step 3 for 50 additional cycles.

Following quantification of the PCR reaction product, the Tm of product was determined and the expected size of product was verified by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel. The product sizes and Tm’s were: Aurka, 135 bp, Tm = 77.5°C; and Egfp, 122 bp, Tm = 85°C. Raw data, without smoothening and with a global minimum base line correction, were imported into Excel, where they were resized for amplitude normalization. The data were fit to a sigmoid curve using NCSS200 statistical software (NCSS, Utah, USA) and initial amount of mRNA was calculated.41 Aurka mRNA expression was normalized to Egfp mRNA and is expressed in relative arbitrary units.

Immunological methods, antibodies and kinase assays

Immunoblot and imunofluorescence methods were used as previously described.35 For AURKA immunoblotting, mouse monoclonal IAK1/AURKA antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories, #610939) was used. For microtubule visualization using immunocytochemistry, mouse monoclonal anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibody (Sigma, T7451) was used. pT288 AURKA was detected by immunocytochemistry using a rabbit anti-phosphorylated T288 AURKA antibody (Novus Biological, NB100-2371) or an anti-phospho-T288 monoclonal AURKA antibody42 for double-staining with phospho-PKB. pS473 PKB was detected by a rabbit polyclonal antibody pAkt-Ser473 (Santa Cruz, SC-7985) and pT308 PKB by a rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-Akt/PKB [pT308] (BioSource, 44-6026). Histone H1 and MAPK assays were performed as previously described.35

Image acquisition and analysis

Live oocytes expressing GFP-AURKA and/or mCHERRYH2B constructs (Figs. 1C and S5) were imaged on inverted fluorescent microscope Olympus IX70 equipped with CCD camera, imunoflurescent images (fixed oocytes) were scanned on Leica TCS2 confocal microscope (Microcope Facility, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Charles University, Praha). Image analysis (profiling) was done using ImageJ software (NIH).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was performed in the frame of IRP IAPG No. AV0Z50450515. It was supported by the GACR grant No. 305/06/1413 and grant ME08030 (Czech-US scientific cooperation program) and HD22681 to R.M.S. A.Š. was also supported by the grant 204/05/H023, V.B. was also supported by VEGA 2/6176/26. We thank to Karel Zvara (Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University in Prague) for help with statistics analysis.

Abbreviations

- AURKA

aurora-A kinase

- GV

germinal vesicle

- GVBD

germinal vesicle breakdown

- IF

immunofluorescence

- MT

microtubule

- MTOC

microtubule-organizing center

- RNAi

RNA interference

Footnotes

Note

Supplementary materials can be found at: www.landesbioscience.com/supplement/SaskovaCC7-15-Sup.pdf

References

- 1.Nigg EA. Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:21–32. doi: 10.1038/35048096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu J, Bian M, Jiang Q, Zhang C. Roles of Aurora kinases in mitosis and tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:1–10. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marumoto T, Zhang D, Saya H. Aurora-A—a guardian of poles. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:42–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen S, Zhou H, White RA. A putative serine/threonine kinase encoding gene BTAK on chromosome 20q13 is amplified and overexpressed in human breast cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 1997;14:2195–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giet R, Petretti C, Prigent C. Aurora kinases, aneuploidy and cancer, a coincidence or a real link? Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:241–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewart-Toland A, Briassouli P, de Koning JP, Mao JH, Yuan J, Chan F, MacCarthy-Morrogh L, Ponder BA, Nagase H, Burn J, Ball S, Almeida M, Linardopoulos S, Balmain A. Identification of Stk6/STK15 as a candidate low-penetrance tumor-susceptibility gene in mouse and human. Nat Genet. 2003;34:403–12. doi: 10.1038/ng1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ewart-Toland A, Dai Q, Gao YT, Nagase H, Dunlop MG, Farrington SM, Barnetson RA, Anton-Culver H, Peel D, Ziogas A, Lin D, Miao X, Sun T, Ostrander EA, Stanford JL, Langlois M, Chan JM, Yuan J, Harris CC, Bowman ED, Clayman GL, Lippman SM, Lee JJ, Zheng W, Balmain A. Aurora-A/STK15 T + 91A is a general low penetrance cancer susceptibility gene: a meta-analysis of multiple cancer types. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1368–73. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang D, Hirota T, Marumoto T, Shimizu M, Kunitoku N, Sasayama T, Arima Y, Feng L, Suzuki M, Takeya M, Saya H. Cre-loxP-controlled periodic Aurora-A overexpression induces mitotic abnormalities and hyperplasia in mammary glands of mouse models. Oncogene. 2004;23:8720–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bischoff JR, Anderson L, Zhu Y, Mossie K, Ng L, Souza B, Schryver B, Flanagan P, Clairvoyant F, Ginther C, Chan CS, Novotny M, Slamon DJ, Plowman GD. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 1998;17:3052–65. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrington EA, Bebbington D, Moore J, Rasmussen RK, Ajose-Adeogun AO, Nakayama T, Graham JA, Demur C, Hercend T, Diu-Hercend A, Su M, Golec JM, Miller KM. VX-680, a potent and selective small-molecule inhibitor of the Aurora kinases, suppresses tumor growth in vivo. Nat Med. 2004;10:262–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda K, Mihara H, Kato Y, Yamaguchi A, Tanaka H, Yasuda H, Furukawa K, Urano T. Degradation of human Aurora2 protein kinase by the anaphase-promoting complex-ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Oncogene. 2000;19:2812–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro A, Arlot-Bonnemains Y, Vigneron S, Labbe JC, Prigent C, Lorca T. APC/Fizzy-Related targets Aurora-A kinase for proteolysis. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:457–62. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crane R, Kloepfer A, Ruderman JV. Requirements for the destruction of human Aurora-A. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5975–83. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter AO, Seghezzi W, Korver W, Sheung J, Lees E. The mitotic serine/threonine kinase Aurora2/AIK is regulated by phosphorylation and degradation. Oncogene. 2000;19:4906–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katayama H, Zhou H, Li Q, Tatsuka M, Sen S. Interaction and feedback regulation between STK15/BTAK/Aurora-A kinase and protein phosphatase 1 through mitotic cell division cycle. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46219–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirota T, Kunitoku N, Sasayama T, Marumoto T, Zhang D, Nitta M, Hatakeyama K, Saya H. Aurora-A and an interacting activator, the LIM protein Ajuba, are required for mitotic commitment in human cells. Cell. 2003;114:585–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao ZS, Lim JP, Ng YW, Lim L, Manser E. The GIT-associated kinase PAK targets to the centrosome and regulates Aurora-A. Mol Cell. 2005;20:237–49. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kufer TA, Sillje HH, Korner R, Gruss OJ, Meraldi P, Nigg EA. Human TPX2 is required for targeting Aurora-A kinase to the spindle. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:617–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trieselmann N, Armstrong S, Rauw J, Wilde A. Ran modulates spindle assembly by regulating a subset of TPX2 and Kid activities including Aurora A activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4791–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai MY, Wiese C, Cao K, Martin O, Donovan P, Ruderman J, Prigent C, Zheng Y. A Ran signalling pathway mediated by the mitotic kinase Aurora A in spindle assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:242–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marumoto T, Honda S, Hara T, Nitta M, Hirota T, Kohmura E, Saya H. Aurora-A kinase maintains the fidelity of early and late mitotic events in HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51786–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du J, Hannon GJ. Suppression of p160ROCK bypasses cell cycle arrest after Aurora-A/STK15 depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8975–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308484101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkissian M, Mendez R, Richter JD. Progesterone and insulin stimulation of CPEB-dependent polyadenylation is regulated by Aurora A and glycogen synthase kinase-3. Genes Dev. 2004;18:48–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.1136004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motlik J, Kubelka M. Cell cycle aspects of growth and maturation of mammalian oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 1990;27:366–75. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080270411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishimoto T. Cell cycle control during meiotic maturation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:654–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han SJ, Conti M. New pathways from PKA to the Cdc2/cyclin B complex in oocytes: Wee1B as a potential PKA substrate. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:227–31. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.3.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma C, Cummings C, Liu XJ. Biphasic activation of Aurora-A kinase during the meiosis I–meiosis II transition in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1703–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1703-1716.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao LJ, Zhong ZS, Zhang LS, Chen DY, Schatten H, Sun QY. Aurora-A is a critical regulator of microtubule assembly and nuclear activity in mouse oocytes, fertilized eggs and early embryos. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1392–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.025155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szollosi D, Calarco P, Donahue RP. Absence of centrioles in the first and second meiotic spindles of mouse oocytes. J Cell Sci. 1972;11:521–41. doi: 10.1242/jcs.11.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manandhar G, Schatten H, Sutovsky P. Centrosome reduction during gametogenesis and its significance. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:2–13. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.031245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuh M, Ellenberg J. Self-organization of MTOCs replaces centrosome function during acentrosomal spindle assembly in live mouse oocytes. Cell. 2007;130:484–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masciarelli S, Horner K, Liu C, Park SH, Hinckley M, Hockman S, Nedachi T, Jin C, Conti M, Manganiello V. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 3A-deficient mice as a model of female infertility. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:196–205. doi: 10.1172/JCI21804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schultz RM, Montgomery RR, Belanoff JR. Regulation of mouse oocyte meiotic maturation: implication of a decrease in oocyte cAMP and protein dephosphorylation in commitment to resume meiosis. Dev Biol. 1983;97:264–73. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han SJ, Vaccari S, Nedachi T, Andersen CB, Kovacina KS, Roth RA, Conti M. Protein kinase B/Akt phosphorylation of PDE3A and its role in mammalian oocyte maturation. EMBO J. 2006;25:5716–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalous J, Solc P, Baran V, Kubelka M, Schultz RM, Motlik J. PKB/AKT is involved in resumption of meiosis in mouse oocytes. Biol Cell. 2006;98:111–23. doi: 10.1042/BC20050020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han SJ, Chen R, Paronetto MP, Conti M. Wee1B is an oocyte-specific kinase involved in the control of meiotic arrest in the mouse. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1670–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duckworth BC, Weaver JS, Ruderman JV. G2 arrest in Xenopus oocytes depends on phosphorylation of cdc25 by protein kinase A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16794–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222661299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lincoln AJ, Wickramasinghe D, Stein P, Schultz RM, Palko ME, De Miguel MP, Tessarollo L, Donovan PJ. Cdc25b phosphatase is required for resumption of meiosis during oocyte maturation. Nat Genet. 2002;30:446–9. doi: 10.1038/ng856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozikowski AP, Sun H, Brognard J, Dennis PA. Novel PI analogues selectively block activation of the pro-survival serine/threonine kinase Akt. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1144–5. doi: 10.1021/ja0285159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomek W, Smiljakovic T. Activation of Akt (protein kinase B) stimulates metaphase I to metaphase II transition in bovine oocytes. Reproduction. 2005;130:423–30. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu W, Saint DA. Validation of a quantitative method for real time PCR kinetics. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:347–53. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohashi S, Sakashita G, Ban R, Nagasawa M, Matsuzaki H, Murata Y, Taniguchi H, Shima H, Furukawa K, Urano T. Phospho-regulation of human protein kinase Aurora-A: analysis using anti-phospho-Thr288 monoclonal antibodies. Oncogene. 2006;25:7691–702. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao LJ, Sun QY. Characterization of aurora-a in porcine oocytes and early embryos implies its functional roles in the regulation of meiotic maturation, fertilization and cleavage. Zygote. 2005;13:23–30. doi: 10.1017/s0967199405003059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uzbekova S, Arlot-Bonnemains Y, Dupont J, Dalbies-Tran R, Papillier P, Pennetier S, Thelie A, Perreau C, Mermillod P, Prigent C, Uzbekov R. Spatio-Temporal Expression Patterns of Aurora Kinases A, B and C and Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation-Element-Binding Protein in Bovine Oocytes During Meiotic Maturation. Biol Reprod. 2007 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.061036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dutertre S, Cazales M, Quaranta M, Froment C, Trabut V, Dozier C, Mirey G, Bouche JP, Theis-Febvre N, Schmitt E, Monsarrat B, Prigent C, Ducommun B. Phosphorylation of CDC25B by Aurora-A at the centrosome contributes to the G2-M transition. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2523–31. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunitoku N, Sasayama T, Marumoto T, Zhang D, Honda S, Kobayashi O, Hatakeyama K, Ushio Y, Saya H, Hirota T. CENP-A phosphorylation by Aurora-A in prophase is required for enrichment of Aurora-B at inner centromeres and for kinetochore function. Dev Cell. 2003;5:853–64. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cazales M, Schmitt E, Montembault E, Dozier C, Prigent C, Ducommun B. CDC25B phosphorylation by Aurora-A occurs at the G2/M transition and is inhibited by DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1233–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou H, Kuang J, Zhong L, Kuo WL, Gray JW, Sahin A, Brinkley BR, Sen S. Tumour amplified kinase STK15/BTAK induces centrosome amplification, aneuploidy and transformation. Nat Genet. 1998;20:189–93. doi: 10.1038/2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meraldi P, Honda R, Nigg EA. Aurora-A overexpression reveals tetraploidization as a major route to centrosome amplification in p53−/− cells. EMBO J. 2002;21:483–92. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirschner MW, Mitchison T. Microtubule dynamics. Nature. 1986;324:621. doi: 10.1038/324621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dumont J, Petri S, Pellegrin F, Terret ME, Bohnsack MT, Rassinier P, Georget V, Kalab P, Gruss OJ, Verlhac MH. A centriole- and RanGTP-independent spindle assembly pathway in meiosis I of vertebrate oocytes. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:295–305. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glover DM, Leibowitz MH, McLean DA, Parry H. Mutations in aurora prevent centrosome separation leading to the formation of monopolar spindles. Cell. 1995;81:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mori D, Yano Y, Toyo-oka K, Yoshida N, Yamada M, Muramatsu M, Zhang D, Saya H, Toyoshima YY, Kinoshita K, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hirotsune S. NDEL1 phosphorylation by Aurora-A kinase is essential for centrosomal maturation, separation and TACC3 recruitment. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:352–67. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.