Abstract

We have previously shown that a pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA)-based vaccine containing DNA plasmid encoding the Flt3 ligand (FL) gene (pFL) as a nasal adjuvant prevented nasal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. In this study, we further investigated the safety and efficacy of this nasal vaccine for the induction of PspA-specific antibody (Ab) responses against lung infection with S. pneumoniae. C57BL/6 mice were nasally immunized with recombinant PspA/Rx1 (rPspA) plus pFL three times at weekly intervals. When dynamic translocation of pFL was initially examined, nasal pFL was taken up by nasal dendritic cells (DCs) and epithelial cells (nECs) but not in the central nervous systems, including olfactory nerve and epithelium. Of importance, nasal pFL induced FL protein synthesis with minimum levels of inflammatory cytokines in the nasal washes (NWs) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). NWs and BALF as well as plasma of mice given nasal rPspA plus pFL contained increased levels of rPspA-specific secretory IgA and IgG Ab responses that were correlated with elevated numbers of CD8+ and CD11b+ DCs and interleukin 2 (IL-2)- and IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells in the nasal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (NALT) and cervical lymph nodes (CLNs). The in vivo protection by rPspA-specific Abs was evident in markedly reduced numbers of CFU in the lungs, airway secretions, and blood when mice were nasally challenged with Streptococcus pneumoniae WU2. Our findings show that nasal pFL is a safe and effective mucosal adjuvant for the enhancement of bacterial antigen (Ag) (rPspA)-specific protective immunity through DC-induced Th2-type and IL-2 cytokine responses.

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a leading human pathogen causing diseases ranging from otitis media to pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis. This bacterium, commonly termed the pneumococcus, can result in an estimated 1.6 million deaths per year worldwide, more than half of which are young children in developing countries (2). Although pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide and pneumococcal protein-capsular conjugate vaccines can provide protective immunity against pneumonia and invasive diseases in adults and infants, a strong need still exists for a new generation of effective vaccines for the prevention of all potential S. pneumoniae infections. In this regard, the multivalent polysaccharide vaccines do not provide protection against strains with nonvaccine serotypes (28, 41). Of importance, pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) has been extensively investigated as a candidate vaccine antigen (Ag) to prevent pneumococcal infection (5, 37). For instance, PspA-specific antibody (Ab) enhances bacterial clearance and induces cross-protection against infection with strains of different serotypes (4, 31). Further, previous studies have demonstrated that PspA-specific Abs overcome the anticomplementary effect of PspA, allowing increased complement activation and C3 deposition on PspA-bearing bacteria (27, 30).

Nasal immunization has been shown to preferentially induce Ag-specific Ab responses in the respiratory tract (20) and other mucosal lymphoid tissues (10, 25, 26). To induce maximal levels of Ag-specific immune responses in both mucosal and systemic lymphoid tissue compartments, it is often necessary to use a mucosal adjuvant (16, 22, 39). Although native cholera toxin and related Escherichia coli enterotoxin are potent mucosal adjuvant for enhancement of Ag-specific immune responses, their application for human use is not warranted since they can cause diarrhea or Bell's palsy (6, 23, 29). Moreover, these toxins are known to migrate into and accumulate in the olfactory tissues when given nasally (40). In this regard, our previous studies demonstrated that nasal application of a DNA plasmid (pFL) containing the gene of the Flt3 ligand (FL), which is a kind of cytokine, preferentially expanded CD8+ dendritic cells (DCs) and subsequently induced Ag-specific mucosal immune responses mediated by interleukin 4 (IL-4)-producing CD4+ T cells when mice were nasally administrated ovalbumin with pFL as the mucosal adjuvant (19). Further, a combination of nasal pFL and CpG oligonucleotides as a double DNA adjuvant enhanced mucosal and systemic immune responses via induction of plasmacytoid DCs as well as CD8+ DCs in mucosal compartments (11, 17). Nasal administration of an adenovirus vector encoding FL cDNA also showed enhancement and maintenance of long-term immunity (17, 32).

In this study, we examined the safety and effectiveness of nasal pFL as a mucosal adjuvant for the induction of functional bacterial Ag (recombinant PspA [rPspA])-specific Ab responses for protection against S. pneumoniae infection in the lower respiratory tract. Our findings show that nasal rPspA plus pFL adjuvant successfully elicits protective immunity in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts by enhancing mucosal DC-mediated Th2-type and IL-2 cytokine responses without detectable cytokine-mediated inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Specific-pathogen-free female C57BL/6 mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Japan (Kanagawa, Japan) and used in this study. Upon arrival, these mice were transferred to microisolators, maintained in horizontal laminar flow cabinets, and provided sterile food and water as part of a specific-pathogen-free facility at Osaka University (Suita, Japan), and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by Osaka University. All of the mice used in these assays were free of bacterial and viral pathogens.

rPspA and adjuvants.

Endotoxin-free rPspA was purified by chromatography on a chelating Sepharose 4B column preloaded with Ni+ (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) from Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) carrying pUAB055, which comprised the first 302 of the 588 amino acids of PspA/Rx1, including all of the α-helical region and some of the proline-rich region (3). The plasmid pORF9-mFlt3L (pFL) consists of the pORF9-mcs vector (pORF) plus the full-length murine FL cDNA gene (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). These plasmids were purified using the Gene Elute endotoxin-free plasmid kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (19). The Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) resulted in <0.1 endotoxin unit of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) per 1 μg of plasmids or rPspA.

Nasal immunization and sample collection.

Mice were immunized three times at weekly intervals nasally with 6 μl/nostril phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 μg of rPspA and 50 μg of pFL as a mucosal adjuvant. As controls, mice were immunized nasally with 50 μg of pORF (empty plasmid) and 5 μg of rPspA under anesthesia. In some experiments, mice were administered pFL (50 μg), pORF (50 μg), rPspA (1 μg or 5 μg), native cholera toxin (nCT) (1 μg), or PBS alone under anesthesia. Plasma, nasal washes (NWs), and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were obtained as described previously (36).

Dynamic translocation of pFL.

On 12 h or 7 days after mice were nasally given pFL (50 μg) alone, mononuclear cells were isolated from nasal mucosa-associated lymphoreticular tissues (NALT) and nasal passages (NPs) as described previously (14, 19), and NALT and NP dendritic cells (DCs) were purified by the AutoMACS cell sorter (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) using anti-CD11c monoclonal Ab (MAb) microbeads (19). Further, nasal epithelial cells (nECs) and olfactory nerves and epithelium (ON/E) were isolated from nasal passages and olfactory bulbs, respectively (14, 40). In brief, cells from the nasal mucosa and olfactory bulb were prepared by gentle teasing through stainless screens and were subjected to discontinuous gradient centrifugation using 40% and 55% Percoll. Cells on the surface of the 40% layer were used as nECs and ON/E. To further confirm the presence of nECs and ON/E, the size and granularity of cells were determined by using flow cytometry. DNA was then extracted from NALT, NP-DCs, nECs, and ON/E, and the ampicillin resistance gene (858 bp) contained in the pFL plasmid was detected by a primer-specific PCR method. The sense primer was 5′-CCA ATG CTT AAT CAG TGA GGC-3′, and the anti-sense primer was 5′-ATG AGT ATT CAA CAT TTC CGT GTC G-3′. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels and visualized by UV light illumination following ethidium bromide (0.5 mg/ml) staining (19).

Analysis of FL protein synthesis.

Twelve hours after nasal administration of pFL (50 μg), empty plasmid (50 μg), rPspA alone, or PBS, DCs from NALT and NPs and nECs and ON/E were purified aseptically as described above and were then cultured for 48 h (2 × 106 cells/ml) in complete medium. The concentrations of FL protein secreted into the medium were determined by FL-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Quantikine M mouse Flt3 ligand ELISA kit; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Mice were next nasally immunized weekly for three consecutive weeks with rPspA (5 μg) plus pFL (50 μg) or pORF (50 μg), rPspA alone (5 μg), or PBS, and 1 week after the last immunization, the FL protein in nasal washes (NWs) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was determined by FL-specific ELISA (R & D Systems).

Detection of inflammatory cytokines in mucosal secretion.

In order to determine inflammatory cytokines by nasal application of pFL, NWs and BALF were collected 5 days after the nasal administration of pFL (50 μg), pORF (50 μg), rPspA (1 μg or 5 μg), or native cholera toxin (1 μg). Next, the mucosal secretion samples were subjected to ELISA specific to IL-1β, IL-6 (R & D Systems), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) according to the manufacturer's instructions (eBioscience, San Diego, CA).

rPspA-specific Ab assays.

In order to examine mucosal and systemic immune responses to Ag, rPspA-specific IgA and IgG antibody (Ab) levels in plasma, NWs, and BALF were determined by ELISA on day 7 after the last immunization, as described previously (18, 19, 32). Briefly, 96-well Falcon microtest assay plates (BD Biosciences, Oxnard, CA) were coated with 1 μg/ml of rPspA in PBS. After incubating serial dilutions of samples, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM, IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, or IgA (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, AL) was added to wells. The color reaction was developed for 15 min at room temperature. Endpoint titers were expressed as the reciprocal log2 of the last dilution that gave an optical density at 415 nm (OD415) of 0.1 greater than the background level. Further, mononuclear cells obtained from spleen, NALT, cervical lymph nodes (CLNs), mediastinal lymph nodes (MeLNs), NPs, and lungs were subjected to an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay in order to determine the numbers of Ag-specific Ab-forming cells (AFCs) (18, 19). In brief, mononuclear cells in the spleen, NALT, CLNs, and MeLNs were isolated aseptically by a mechanical dissociation method using gentle teasing through stainless steel screens as described previously (14). For isolation of mononuclear cells from NPs, a modified dissociation method was used based upon a previously described protocol (18). Mononuclear cells from lungs were isolated by a combination of an enzymatic dissociation procedure with collagenase type IV (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) followed by discontinuous Percoll (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL) gradient centrifugation.

Flow cytometric analysis.

To characterize the phenotype of DCs, aliquots of mononuclear cells (0.2 × 106 to 1.0 × 106 cells) were isolated from various lymphoid compartments 1 week after the last immunization with rPspA plus pFL or pORF. The cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b, CD8, or B220 MAbs (BD Biosciences). In some experiments, mononuclear cells were incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-mouse I-Ab, CD11c, CD40, CD80, or CD86 MAbs (BD Biosciences) and biotinylated anti-mouse CD11c MAbs (BD Biosciences), followed by CyChrome-streptavidin. These samples were then subjected to flow cytometry analysis (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences) for cell subset analysis (19).

rPspA-specific CD4+ T cell responses and cytokine-specific ELISA.

CD4+ T cells from lungs, CLNs, and spleen were purified using an automatic cell sorter (AutoMACS) system (Miltenyi Biotec) as described previously (18, 19). The purified CD4+ T cell fraction (>97% CD4+ and >99% viable) was resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with HEPES buffer (10 mM), l-glutamine (2 mM), nonessential amino acid solution (10 μl/ml), sodium pyruvate (10 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), gentamicin (80 μg/ml), and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (complete medium; 4 × 106 cells/ml) and cultured in the presence of T cell-depleted, complement- and mitomycin-treated splenic Ag-presenting cells taken from nonimmunized, normal mice with or without 2 μg/ml rPspA. To assess rPspA-specific T cell proliferative responses, an aliquot of 0.5 μCi of tritiated [3H]TdR (PerkinElmer Japan Co., Ltd., Japan) was added during the final 18 h of incubation, and the amount of [3H]TdR incorporation was determined by scintillation counting (19). The culture supernatants were collected on day five and analyzed using gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-, IL-2-, IL-4-, IL-5-, IL-6-, and IL-10-specific ELISA kits (eBioscience). The detection limit for each cytokine was as follows: 15 pg/ml for IFN-γ, 2 pg/ml for IL-2, 4 pg/ml for IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6, and 30 pg/ml for IL-10.

Pneumococcal infection.

Mice were nasally challenged with a serotype 3 S. pneumoniae strain (WU2) with a mucoid phenotype at a dose of 1.8 × 107 CFU (20 μl). Forty-eight hours after the bacterial challenge, the lungs were removed aseptically and homogenized in 9 ml of sterile saline per gram of lung tissues. NWs and blood were collected as described above. Bacterial colonies were counted by plating lungs, NWs, and blood (50 μl, respectively) on horse blood agar (BD Biosciences), followed by incubation at 37°C overnight. The detection limit of bacterial culture was 102 CFU/g. The 50% lethal dose was calculated to be 2.5 × 106 CFU.

Statistical analysis.

Each result is expressed as the mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (SEM). All mouse groups were compared with control mice using an unpaired Mann-Whitney U test by using the Statview software program (Abacus Concepts, Cary, NC), designed for Macintosh computers, with Bonferroni's correction. P values of <0.05 or <0.01 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Tracking plasmid expression and FL protein synthesis.

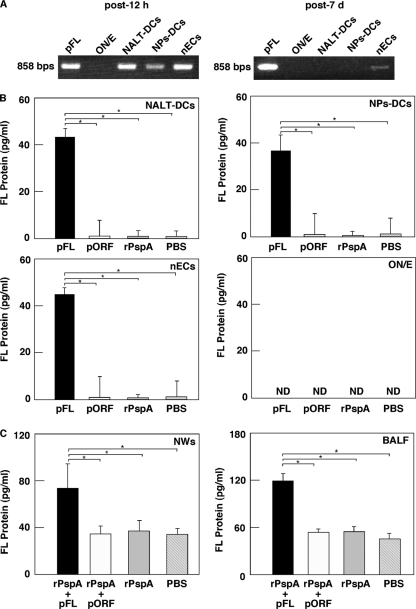

In order to examine safety of pFL for nasal application, we initially traced plasmid-specific ampicillin resistance gene expression by nasal DCs, nECs, and the ON/E. DCs from NALT and NPs, as well as nECs, possessed the ampicillin resistance gene 12 h after nasal administration of pFL (Fig. 1A, left). Of interest, on 7 days after nasal pFL application, the ampicillin resistance gene was detected only in nECs (Fig. 1A, right). Further, NALT-DCs, NP-DCs, and nECs of mice given nasal pFL produced significantly elevated levels of the FL protein compared with those of mice given nasal pORF (empty plasmid), rPspA alone, or PBS (Fig. 1B). In addition, nasal application of the combination of rPspA and pFL resulted in FL protein production comparable to that with nasal application of pFL alone (data not shown). However, FL protein synthesis in mice given nasal rPspA plus pORF was at essentially the same level as that seen in mice given pORF or rPspA alone (data not shown). Thus, NWs and BALF from mice given nasal pFL plus rPspA contained significantly higher levels of FL than those from mice given nasal pORF plus rPspA, rPspA alone, or PBS only (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, of importance, no plasmid-specific genes were essentially detected in the ON/E of mice given nasal pFL (Fig. 1A). Thus, the culture supernatants of ON/E did not contain detectable levels of the FL protein (Fig. 1B). These results show that pFL is largely present in nasal DCs and nECs but not in the ON/E and suggest that pFL on nECs may maintain production of the FL protein.

Fig. 1.

(A to C) Translocation of FL plasmid after nasal administration of pFL (A), FL protein production by nasal DCs and epithelial cells (B), and expression of the FL protein in mucosal secretions (C). (A) Twelve hours (left) or 7 days (right) after nasal application of pFL (50 μg), the DNA samples were extracted from 1.0 × 105 (each) cells of the olfactory nerve and epithelium (ON/E; lane 2), NALT-DCs (lane 3), NPs-DCs (lane 4), and nasal epithelial cells (nECs; lane 5). In order to show the presence of plasmid in these cell populations, the ampicillin resistance gene (858 bp) contained in pFL was detected by PCR using specific primers. pFL (0.1 μg) was employed as a positive control (lane 1). (B) Mice were nasally administered pFL (50 μg; black column), pORF (50 μg; white column), rPspA (5 μg; shaded column), or PBS (hatched column). Twelve hours later, NALT-DCs, NPs-DCs, nECs, and ON/E were isolated and cultured (2 × 106 cells/ml, respectively) for 48 h in complete medium. The concentration of FL protein secreted in medium was measured by FL-specific ELISA. The values shown are the means ± SEM for 30 mice for each group and a total of three experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with results for the mouse group given pORF, rPspA, or PBS. (C) Mice were nasally immunized weekly for three consecutive weeks with rPspA (5 μg) plus pFL (50 μg; black column) or pORF (50 μg; white column), rPspA alone (5 μg; shaded column), or PBS (hatched column). One week after the last immunization, NWs and BALF (100 μl, respectively) were collected and subjected to FL-specific ELISA. The values shown are the means ± SEM of data for 30 mice for each group and a total of three experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with results for mouse group given pORF, rPspA, or PBS.

Nasal pFL induces lower levels of inflammatory cytokines than nCT.

Although pFL was not taken up by the central nervous system, it is important to show that FL produced in the nasal cavity does not induce inflammatory responses. In this regard, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α production in NWs and BALF were examined 5 days after nasal administration with rPspA, pORF, native cholera toxin (nCT), or pFL. The levels of inflammatory cytokine synthesis in NWs and BALF of mice given nasal pFL were essentially the same as or lower than that of mice given nasal rPspA or pORF alone (Fig. 2). Similarly, nasal application of rPspA plus pFL resulted in low levels of inflammatory cytokine production which were similar to those seen in pFL alone (data not shown). Conversely, nasal nCT induced markedly high levels of these inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2). These results show that nasal pFL application does not elicit unnecessary inflammatory responses in the nasal mucosa.

Fig. 2.

Inflammatory cytokine production in NWs (white column) and BALF (black column). Mice were nasally administered native cholera toxin (nCT) (1 μg), rPspA (1 or 5 μg), pORF (50 μg), or pFL (50 μg). Five days later, NWs and BALF were collected and subjected to IL-1β-, IL-6-, and TNF-α-specific ELISA. The values shown are the means ± SEM of data for 30 mice for each group and total of three experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared with results for mouse group given nCT).

Induction of rPspA-specific Ab responses in mucosal and systemic tissues of mice given rPspA plus pFL.

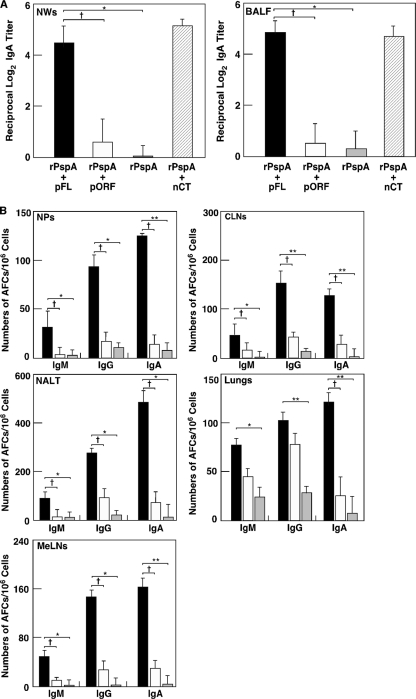

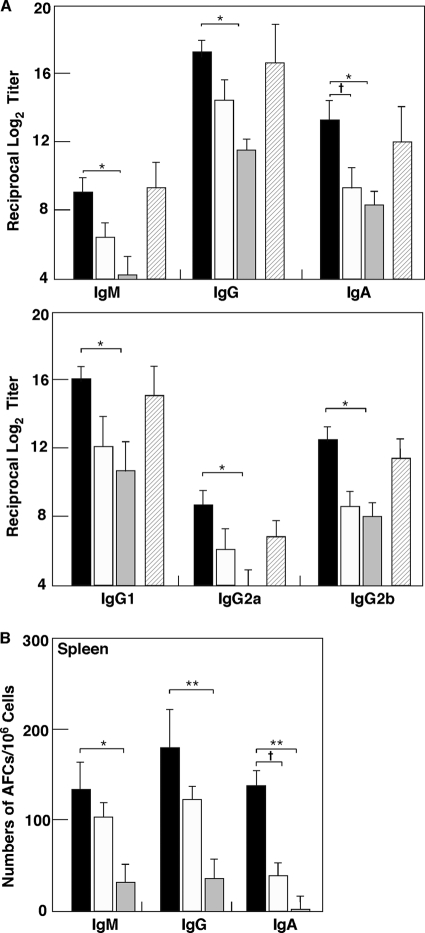

We next examined whether nasal administration of pFL as a mucosal adjuvant would enhance rPspA-specific Ab responses. Giving mice nasal rPspA plus pFL resulted in significantly increased levels of rPspA-specific IgA Ab responses in NWs and BALF compared with results for mice given nasal rPspA plus pORF or rPspA Ag alone (Fig. 3A). The levels of rPspA-specific IgA Ab responses for mice given rPspA plus pFL were comparable to those seen for mice given nasal nCT vaccination (Fig. 3A). To further support these findings, elevated numbers of PspA-specific IgA AFCs were detected in NPs, CLNs, NALT, lungs, and MeLNs of mice given nasal rPspA and pFL (Fig. 3B). In addition, significantly higher numbers of rPspA-specific IgG and/or IgM AFCs were seen for mice given pFL as a nasal adjuvant than for mice given nasal pORF or rPspA alone (Fig. 3B). These results clearly show that pFL as a nasal adjuvant effectively elicits rPsp-specific Ab responses in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues in the respiratory tract. Since nasal immunization is known to induce systemic immunity in addition to the mucosa, rPspA-specific Ab responses in plasma and spleen were examined. Nasal pFL as a mucosal adjuvant successfully enhanced rPspA-specific IgG and IgA Ab responses in plasma which are comparable to those responses seen in mice given nasal rPspA plus nCT (Fig. 4A). Thus, significantly increased numbers of rPspA-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA AFCs were seen in spleen of mice given pFL as a nasal adjuvant (Fig. 4B). When the levels of rPspA-specific IgG subclass Ab responses were examined, increased levels of anti-rPspA IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b Abs were noted for mice given nasal rPspA plus pFL compared with those Ab responses for mice given rPspA plus pORF or rPspA alone (Fig. 4A). Essentially no IgG3 Ab response against rPspA was detected. Taken together, pFL as a nasal adjuvant effectively induces rPspA-specific Ab responses in both mucosal and systemic immune compartments.

Fig. 3.

Mucosal immune responses to rPspA in external secretions and mucosal lymphoid tissues. C57BL/6 mice were nasally immunized three times at weekly intervals with rPspA (5 μg) plus pFL (50 μg; black column) or pORF (50 μg; white column), rPspA alone (shaded column), or rPspA (5 μg) plus nCT (1 μg; hatched column). (A) Seven days after the last immunization, the levels of rPspA-specific IgA Abs in NWs and BALF were determined by rPspA-specific ELISA. (B) Seven days after the last immunization, mononuclear cells isolated from NPs, CLNs, NALT, lungs, and MeLNs were subjected to ELISPOT assay to determine the numbers of Ag-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA Ab-forming cells (AFCs). The values shown are the means ± SEM (n = 20). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared with mouse group given rPspA alone). †, P < 0.05 (compared with mouse group given rPspA plus pORF).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of rPspA-specific Ab responses in plasma and spleen cells of mice given nasal rPspA plus pFL (black column) or pORF (white column), rPspA alone (shaded column), or rPspA plus nCT (hatched column). Each mouse group was nasally immunized weekly for three consecutive weeks. (A) Seven days after the last immunization, rPspA-specific IgM, IgG, IgA, and IgG subclass Ab responses in plasma were determined by Ag-specific ELISA. An rPspA-specific IgG3 Ab response was not detected. (B) Seven days after the last immunization, mononuclear cells were isolated from spleens and were then subjected to ELISPOT assay to determine numbers of rPspA-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA AFCs. The values shown are the means ± SEM (n = 20). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared with results for mouse group given rPspA alone). †, P < 0.05 (compared with results for mouse group given rPspA plus pORF).

Nasal rPspA plus pFL leads CD11b+ and CD8+ DCs.

Since our previous studies reported that nasal pFL plus ovalbumin as an Ag elicited expansion of CD8-expressing lymphoid-type CD11c+ DCs (19), we next characterized CD11c+ DCs in the various mucosal tissues of mice given rPspA plus pFL or pORF. Nasal immunization of rPspA plus pFL significantly increased the frequency of CD11c+ cells in both mucosal and systemic tissues compared with results for mice given rPspA plus pORF (Table 1). Interestingly, the numbers of CD8+ DCs were increased in all tissues of mice given pFL as a nasal adjuvant compared with those numbers for mice given nasal pORF. In addition, increased frequencies of CD11b+ DCs were noted in NALT, NPs, CLNs, and spleen. In contrast, increased frequencies of B220+ DCs were seen only in CLNs (Table 1). Further, higher expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II), CD40, CD80, and CD86 was seen on CD11c+ DCs (Table 1). CD8+ and CD11b+ DCs from NALT, lungs, and NPs were also examined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for expression of costimulatory molecules. Our results showed increased frequencies of costimulatory molecule expression by CD8+ and CD11b+ DCs in the tissues of mice given nasal pFL compared with those in control groups (Table 2). Taken together, these results indicate that nasal administration of rPspA plus pFL preferentially expands the numbers of CD8+ and CD11b+ DC populations which express elevated levels of costimulatory molecules.

Table 1.

Frequencies of CD11c+ DCs and CD8, CD11b, B220, and costimulatory molecule expression by CD11c+ DCs of mucosal effector and inductive tissues of mice given nasal rPspA with pFL or pORFa,e

| Tissue source | Adjuvant given with nasal rPspA | % CD11c+ total lymphocytesb | % CD11c+ DCs expressing: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8c | CD11bc | B220c | CD40d | CD80d | CD86d | MHC IId | |||

| NALT | pFL | *6.6 ± 1.7 | *23.5 ± 3.7 | *23.1 ± 3.1 | 56.5 ± 6.2 | **3.1 ± 0.7 | 10.9 ± 4.5 | *19.3 ± 4.8 | **68.9 ± 8.2 |

| pORF | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 12.1 ± 1.6 | 12.3 ± 3.9 | 50.4 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 8.9 ± 2.6 | 45.9 ± 1.9 | |

| Lungs | pFL | *5.7 ± 1.3 | *12.4 ± 2.4 | 68.6 ± 4.1 | 24.8 ± 3.5 | *4.6 ± 1.1 | *15.2 ± 5.6 | *20.8 ± 3.6 | *51.5 ± 9.6 |

| pORF | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 7.7 ± 0.9 | 63.9 ± 3.9 | 20.6 ± 4.7 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 6.9 ± 2.4 | 9.5 ± 7.9 | 39.1 ± 0.7 | |

| NPs | pFL | *10.1 ± 2.4 | *22.1 ± 2.3 | *60.1 ± 6.9 | 19.3 ± 3.7 | *11.1 ± 3.3 | *23.8 ± 3.5 | 25.9 ± 6.2 | 38.5 ± 4.2 |

| pORF | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 14.8 ± 3.8 | 31.1 ± 6.0 | 20.6 ± 4.7 | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 17.8 ± 0.1 | 23.1 ± 7.6 | 33.3 ± 1.9 | |

| CLNs | pFL | *2.3 ± 0.4 | *32.8 ± 3.6 | *31.8 ± 3.6 | *45.4 ± 4.1 | **3.1 ± 0.2 | **24.7 ± 1.0 | *43.3 ± 2.9 | 87.4 ± 5.9 |

| pORF | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 21.1 ± 3.6 | 24.8 ± 3.2 | 33.3 ± 4.5 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 10.6 ± 1.3 | 28.5 ± 8.5 | 85.3 ± 0.6 | |

| Spleen | pFL | *2.4 ± 0.7 | *21.7 ± 2.2 | *33.4 ± 5.1 | 44.6 ± 3.5 | *4.3 ± 2.0 | 20.3 ± 6.4 | **26.4 ± 5.3 | **87.5 ± 1.5 |

| pORF | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 18.2 ± 0.9 | 25.2 ± 3.4 | 39.9 ± 3.5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 12.9 ± 0.6 | 11.4 ± 2.8 | 75.0 ± 4.2 | |

Mononuclear cells from NALT, lungs, NPs, CLNs, and spleens of mice immunized with rPspA plus pFL or pORF were stained with a combination of anti-CD11c and the respective MAb and subjected to FACSCalibur flow cytometry analysis.

Mononuclear cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD11c MAb and subjected to flow cytometry analysis.

Mononuclear cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD8α, -CD11b, and -B220 MAb and PE-labeled anti-CD11c.

Mononuclear cells were stained with PE-labeled anti-CD40, -CD80, -CD86 or I-A and biotinylated anti-mouse CD11c MAb followed by CyChrome-streptavidin.

*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared with those of mice immunized with rPspA plus pORF).

Table 2.

Frequencies of costimulatory molecule expression on CD8 or CD11b DCs in mucosal effector and inductive tissues of mice given nasal rPspA with pFL or pORFa

| Tissue source | Adjuvant given with nasal rPspA | % CD11c+ DCs |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ DCs |

CD11b+ DCs |

||||||||

| CD40 | CD80 | CD86 | MHC II | CD40 | CD80 | CD86 | MHC II | ||

| NALT | pFL | **1.4 ± 0.1 | *4.4 ± 0.6 | *9.5 ± 1.4 | **34.5 ± 2.2 | **1.3 ± 0.1 | *4.1 ± 0.3 | *8.5 ± 1.7 | *27.3 ± 4.2 |

| pORF | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 12.4 ± 1.3 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 14.6 ± 1.5 | |

| Lungs | pFL | *1.7 ± 0.2 | **7.7 ± 0.3 | **7.5 ± 0.4 | **18.7 ± 3.1 | *1.4 ± 0.2 | *6.6 ± 0.9 | *8.0 ± 0.8 | *30.5 ± 3.8 |

| pORF | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 14.5 ± 5.7 | |

| NPs | pFL | *5.8 ± 0.4 | *8.2 ± 1.7 | *9.8 ± 1.5 | *14.8 ± 2.4 | *4.5 ± 1.1 | *13.1 ± 2.0 | 11.5 ± 3.3 | *20.6 ± 3.5 |

| pORF | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 7.3 ± 1.9 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 8.7 ± 2.0 | 12.0 ± 2.2 | |

CD11c-positive DCs from NALT, lungs, and NPs of mice immunized with rPspA plus pFL or pORF were purified from mononuclear cells by using the automatic cell sorter system AutoMacs and were stained with a combination of FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD8α MAb or anti-mouse CD11b MAb and PE-labeled anti-CD40, -CD80, -CD86, or I-A and subjected to FACSCalibur flow cytometry analysis. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared with those of mice immunized with rPspA plus pORF).

Th1- and Th2-type cytokine responses by PspA-specific CD4+ T cells.

We next assessed rPspA-specific CD4+ T cell responses induced by pFL as a mucosal adjuvant. rPspA-stimulated CD4+ T cells from lungs, CLNs, and spleen of mice given nasal rPspA plus pFL showed significantly higher proliferative responses than did those from mice nasally immunized with rPspA plus pORF (Table 3). In this regard, when Th1- and Th2-type cytokine profiles were examined, PspA-stimulated CD4+ T cells from mice given pFL as a nasal adjuvant exhibited higher levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6 production than those in control mice. On the other hand, levels of IFN-γ production by PspA-stimulated CD4+ T cells were essentially the same between mice given pFL or pORF (Table 3). Intracellular IL-17 analysis revealed that no significant increase in the frequency of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells was seen in CLNs and spleen of mice given nasal pFL compared with results for mice given empty plasmid as a nasal adjuvant (data not shown). These results show that pFL as a nasal adjuvant preferentially induces Th2-type dominant cytokine responses in the lower respiratory mucosa when rPspA is used as an Ag for nasal vaccination.

Table 3.

CD4+ Th1- and Th2-type cytokine responses after in vitro restimulation with rPspAa

| Tissue | Nasal adjuvant | Stimulation indexb | Production of Th1- or Th2-type cytokinec |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ (ng/ml) | IL-2 (pg/ml) | IL-4 (pg/ml) | IL-5 (pg/ml) | IL-6 (ng/ml) | IL-10 (ng/ml) | |||

| Lungs | pFL | *5.5 ± 1.8 | 2.03 ± 0.40 | *249.8 ± 48.8 | *56.7 ± 9.4 | *255.7 ± 76.9 | *1.80 ± 0.49 | 1.19 ± 0.32 |

| pORF | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 1.48 ± 0.24 | 130.1 ± 35.7 | 21.2 ± 4.4 | 86.6 ± 22.0 | 0.78 ± 0.29 | 0.89 ± 0.34 | |

| CLNs | pFL | *6.1 ± 1.3 | 1.63 ± 0.24 | *201.3 ± 55.3 | *55.6 ± 14.9 | *314.5 ± 66.6 | 1.51 ± 0.68 | 1.43 ± 0.41 |

| pORF | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 1.13 ± 0.18 | 78.8 ± 13.6 | 18.8 ± 5.40 | 66.5 ± 28.8 | 0.72 ± 0.34 | 1.21 ± 0.47 | |

| Spleen | pFL | *4.8 ± 1.4 | 1.65 ± 0.47 | *391.1 ± 68.9 | *45.1 ± 10.5 | *286.8 ± 53.4 | *1.33 ± 0.50 | 1.57 ± 0.39 |

| pORF | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.22 ± 0.39 | 53.3 ± 19.1 | 16.1 ± 6.20 | 57.7 ± 15.1 | 0.89 ± 0.42 | 1.40 ± 0.24 | |

The CD4+ T cells (4 × 106 cells/ml) from lungs, CLNs, and spleen were isolated 7 days after the last immunization with rPspA (5 μg) and pFL or pORF as a mucosal adjuvant and cultured with T cell depleted feeder cells (8 × 106 cells/ml). Values are presented as means ± SEM of data from 30 mice for each group and a total of three experiments. *, P < 0.05 when compared with mice given rPspA plus pORF.

Proliferative responses of CD4+ T cells from mice nasally immunized with rPspA plus pFL or pORF as a mucosal adjuvant were represented as the stimulation index by measuring counts per minute (cpm) of wells with or without rPspA (control). The levels of [3H]TdR incorporation for each control well were between 500 and 1,000 cpm. The results show the individual values from these separate experiments of 30 mice per experimental group.

The culture supernatant were harvested after 48 h of incubation and subjected to the respective cytokine ELISAs.

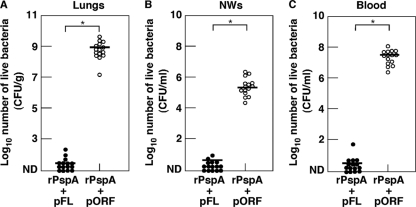

Protection against S. pneumoniae infection by nasal vaccination with rPspA plus pFL.

In order to determine the functional properties of nasal vaccination with rPspA plus pFL, mice were challenged with S. pneumoniae strain WU2 (1.8 × 107 CFU/20 μl) 1 week after the last vaccination. When the bacterial densities in the lungs, NWs, and blood were examined 48 h after nasal challenge, mice given nasal rPspA plus pFL showed significantly lower bacterial density. Conversely, lungs, NWs, and blood of mice given rPspA plus pORF contained high numbers of S. pneumoniae bacteria (Fig. 5). These results show that nasal rPspA plus pFL provides effective protection against S. pneumoniae infection at the lung and nasal mucosa.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of protective effects against S. pneumoniae infection with nasal pFL-based rPspA vaccine. One week after the last immunization with rPspA plus pFL (closed circle) or pORF (open circle), mice were challenged with 1.8 × 107 CFU of the WU2 strain. (A) Forty-eight hours after bacterial challenge, the lungs were removed aseptically and homogenized in 9 ml of sterile saline per gram of lung tissue for the culture. (B) NWs were harvested aseptically by flushing with 1 ml of PBS and cultured on agar medium. (C) Blood samples were plated on agar medium from the culture. The detection limit of bacterial cultures was 102 CFU/g. The values shown are the means ± SEM (n = 15). Each line represents the median log10 CFU/mouse. *, P < 0.05, compared with mouse group given rPspA plus pORF.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have investigated whether nasal pFL as a mucosal adjuvant elicits functional bacterial Ag (rPspA)-specific Ab responses for protection against S. pneumoniae infection. Our results clearly showed that nasal vaccination with rPspA plus pFL elicited DC-mediated Th2-type and IL-2 cytokine responses and subsequent anti-rPspA Abs for protection against pneumococcal infection at the pulmonary mucosa. Since a risk of central nervous system toxicity is one of the major issues for nasal vaccine development (6, 9, 29), we also examined pFL uptake and inflammatory cytokine synthesis in the nasal mucosa. Our results indicated that nasal pFL was taken up only by NALT and NP DCs, as well as nECs, but not by ON/E. Further, minimal levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α production were induced in NWs of mice given pFL. Taken together, the current study is the first to show that nasal pFL is a safe mucosal adjuvant that effectively elicits bacterial Ag (PspA)-specific functional Ab responses that are potent for the prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia and bacteremia.

We recently showed that pFL as a nasal adjuvant elicited PspA-specific S-IgA Ab responses in the nasal cavity to prevent nasal carriage of S. pneumoniae (12). Although the recent study clearly indicated the potential of pFL as a nasal adjuvant for a pneumococcal vaccine, it still remained to be elucidated whether pFL can induce protection in the lower respiratory mucosa, including the lungs. In this regard, nasal pFL elicited functional rPspA-specific S-IgA Ab responses in the BALF and lungs when mice given nasal rPspA plus pFL were nasally challenged with a large amount (20 μl; 1.8 × 107 CFU) of WU2 (invasive strain), allowing bacterial exposure to the lungs. Thus, mice given nasal rPspA plus pFL showed a significantly lower number of bacteria in the BALF after being challenged fatally with WU2 than did mice given empty plasmid as a nasal adjuvant. Based upon our previous studies and those of others (12, 42), we expected that nasal immunization with rPspA plus pFL induced Ag-specific functional S-IgA Ab responses in the nasal cavity. Indeed, a remarkable anti-rPspA S-IgA Ab induction and the inhibition of bacterial growth were seen in NWs after bacterial challenge. Thus, it is possible that an effective inhibition of nasopharyngeal bacterial colonization might lead to drastic reduction of bacterial growth in the lungs and prevention of subsequent bacteremia. In any case, the presence of anti-PspA IgA Abs in the lower and upper respiratory mucosa is the fundamental factor to prevent bacterial invasion of the hosts.

The FL protein is known as a synergistic hematopoietic growth factor that has emerged as a potential immunomodulator (8, 21, 38) and can expand DC populations and enhance antigen-presenting cell (APC) activity (13, 24). In addition, it was recently reported that percutaneous administration of the FL protein regulated migration and Ag uptake of lung DCs (34, 35). In this regard, our previous studies showed that nasal pFL increases the frequency of CD8+ DCs in various mucosal and systemic lymphoid tissues (11, 19). Our present study showed increased numbers of CD8+ DCs, which agrees with these previous findings even though a bacterial Ag was used as a component of the nasal vaccine. Since a recent study indicated that induction of CD8+ DCs promoted protection against respiratory infection (7), it is possible that induction of CD8+ DCs in the mucosal and systemic compartments contributes to S. pneumoniae clearance in the respiratory tract and blood. Further, increased frequencies of CD11b+ DCs were also seen in mice given nasal rPspA plus pFL. Recent reports showed that the interactions between CD4+ T cells and DCs play a key role in the induction of pulmonary immunity (1) and that DCs polarize initial CD4+ T cell activation toward Th2-type immune responses (33). Further, our previous and present studies showed that nasal pFL elicited CD8+ DC-mediated Th2-type responses. In this regard, it is possible that CD11b+ DCs play a role in the downregulation of Th2-prone cytokine responses for the maintenance of mucosal homeostasis. Indeed, it was suggested that FL treatment induced Th2-suppressive lung CD11b+ DCs (15, 35). Further, nasal application of FL-expressing adenovirus as a mucosal adjuvant preferentially expands CD11b+ DCs to produce a balanced Th1- and Th2-type cytokine response (32). The actual immunoregulatory functions of CD11b+ DCs induced by nasal pFL are currently being tested in our laboratory.

In summary, the present study shows that pFL as a nasal adjuvant induces enhanced PspA-specific immunity in the nasal-pulmonary mucosa via CD8+ and CD11b+ DC subset-mediated Th2-type cytokines responses. Importantly, nasal vaccination with rPspA plus pFL inhibits bacterial growth in the lungs and nasal cavities of mice in order to prevent the early phases of pneumococcal pneumonia without CNS toxicity or inflammation. These findings suggest that pFL is a safe nasal adjuvant for use in the future development of vaccines that can induce enhanced specific immunity against bacterial and viral Ags.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jerry R. McGhee and Rebekah S. Gilbert for scientific discussion, critiques, and editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

This work is supported by NIH grants AG 025873 and DE 012242 and a Grant-in Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (22659383) and grant B-23390481 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Scholarship of the Fujii-Otsuka Foundation for International Research, as well as the Biomedical Cluster Kansai project, which is promoted by the Regional Innovation Cluster Program, subsidized by the Japanese Government and the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NIBIO).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bakocevic N., Worbs T., Davalos-Misslitz A., Forster R. 2010. T cell-dendritic cell interaction dynamics during the induction of respiratory tolerance and immunity. J. Immunol. 184:1317–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bogaert D., de Groot R., Hermans P. W. M. 2004. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4:144–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Briles D. E., et al. 2000. Intranasal immunization of mice with a mixture of the pneumococcal proteins PsaA and PspA is highly protective adjuvant nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 68:796–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Briles D. E., et al. 2000. Immunization of human recombinant pneumococcal surface protein A (rPspA) elicits antibodies that passively protect mice from fatal infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae bearing heterologous PspA. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1694–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Briles D. E., et al. 1996. Systemic and mucosal protective immunity to pneumococcal surface protein A. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 797:118–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Couch R. B. 2004. Nasal vaccination, Escherichia coli enterotoxin, and Bell's palsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:860–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunne P. J., Moran B., Cummins R. C., Mills K. H. G. 2009. CD11c+ CD8+ dendritic cells promote protective immunity to respiratory infection with Bordetella pertussis. J. Immunol. 183:400–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edwan J. H., Perry G., Talmadge J. E., Agrawal D. K. 2004. Flt-3 ligand reverses late allergic response and airway hyper-responsiveness in a mouse model of allergic inflammation. J. Immunol. 172:5016–5023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fujihashi K., Koga T., van Ginkel F., Hagiwara Y., McGhee J. R. 2002. A dilemma for mucosal vaccination: efficacy versus toxicity using enterotoxin- based adjuvants. Vaccine 20:2431–2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fujihashi K., et al. 1996. gamma/delta T cell-deficient mice have impaired mucosal IgA responses. J. Exp. Med. 183:1929–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fukuiwa T., et al. 2008. A recombination of Flt3 ligand cDNA and CpG ODN as nasal adjuvant elicits NALT dendritic cells for prolonged mucosal immunity. Vaccine 26:4849–4859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fukuyama Y., et al. 2010. Secretory-IgA antibodies play an important role in the immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Immunol. 185:1755–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gilliland D. G., Griffin J. D. 2002. The roles of FLT3 in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Blood 100:1532–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hagiwara H., et al. 2006. A second generation of double mutant cholera toxin adjuvants: enhanced immunity without intracellular trafficking. J. Immunol. 177:3045–3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hammad H., et al. 2004. Differential capacity of CD8a+ or CD8a− dendritic cell subsets to prime for eosinophilic airway inflammation in the T-helper type 2-prone milieu of the lung. Clin. Exp. Allergy 34:1834–1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Imaoka K., et al. 1998. Nasal immunization of nonhuman primates with simian immunodeficiency virus p55 gag and cholera toxin adjuvant induces Th1/Th2 help for virus-specific immune responses in reproductive tissues. J. Immunol. 161:5952–5958 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kataoka K., Fujihashi K. 2009. Dendritic cell-targeting DNA-based mucosal adjuvants for the development of mucosal vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 8:1183–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kataoka K., et al. 2007. Nasal cholera toxin elicits IL-5 and IL-5 receptor a-chain expressing B-1a B cells for innate mucosal IgA antibody responses. J. Immunol. 178:6058–6065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kataoka K., et al. 2004. Nasal Flt3 ligand cDNA elicits CD11c+ CD8+ dendritic cells for enhanced mucosal immunity. J. Immunol. 172:3612–3619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kurono Y., et al. 1999. Nasal immunization induces Haemophilus influenzae-specific Th1 and Th2 responses with mucosal IgA and systemic IgG antibodies for protective immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 180:122–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kutzler M. A., Weiner D. B. 2004. Developing DNA vaccines that call to dendritic cells. J. Clin. Invest. 114:1241–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Langermann S., Palaszynsky S., Sadzience A., Stover C., Koenig S. 1994. Systemic and mucosal immunity induced by BCG vector expressing outer-surface protein A of Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 372:552–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lewis D. J. M., et al. 2009. Transient facial nerve paralysis (Bell's palsy) following intranasal delivery of a genetically detoxified mutant of Escherichia coli heat labile toxin. PLoS One. 4(9):e6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maraskovsky E., et al. 1996. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J. Exp. Med. 184:1953–1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGhee J. R., et al. 1992. The mucosal immune system: from fundamental concepts to vaccine development. Vaccine 10:75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mestecky J., Blumberg R. S., Kiyono H., McGhee J. R. 2003. The mucosal immune system, p. 965–1020 In Paul W. E. (ed.), Fundamental immunology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moreno A. T., et al. 2010. Immunization of mice with single PspA fragments induces antibodies capable of mediating complement deposition on different pneumococcal strains and cross-protection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:439–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Musher D. M., Rueda A. M., Nahm M. H., Gravis E. A., Rodriguez-Barradas M. C. 2008. Initial and subsequent response to pneumococcal polysaccharide and protein-conjugate vaccines administered sequentially in adults who have recovered from pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 198:1019–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mutsch M., et al. 2004. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell's palsy in Switzerland. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:896–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ren B. A., Szalai J., Hollingshead S. K., Briles D. E. 2004. Effects of PspA and antibodies to PspA on activation and deposition of complement on the pneumococcal surface. Infect. Immun. 72:114–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roche A. M., Weiser J. N. 2010. Identification of the targets of cross-reactive antibodies induced by Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization. Infect. Immun. 78:2231–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sekine S., et al. 2008. A novel adenovirus expressing Flt3 ligand enhances mucosal immunity by inducing mature nasopharyngeal-associated lymphoreticular tissue dendritic cell migration. J. Immunol. 180:8126–8134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sen D., Forrest L., Kepler T. B., Parker I., Cahalan M. D. 2010. Selective and site-specific mobilization of dermal dendritic cells and langerhans cells by Th1- and Th2-polarizing adjuvants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:8334–8339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shao Z., Bharadwaj A. S., McGee H. S., Makinde T. L., Agrawal D. K. 2009. Flt-3 ligand increases a lung dendritic cell subset with regulatory properties in allergic airway inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123:917–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shao Z., Makinde T. O., McGee H. S., Wang X., Agrawal D. K. 2009. Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand regulates migratory pattern and antigen uptake of lung dendritic cell subsets in a murine model of allergic airway inflammation. J. Immunol. 183:7531–7538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Takahashi E., et al. 2010. Attenuation of inducible respiratory immune responses by oseltamivir treatment in mice infected with influenza A virus. Microbes Infect. 12:778–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tart R. C., McDaniel L. S., Ralph B. A., Briles D. E. 1996. Truncated Streptococcus pneumoniae PspA molecules elicit cross-protective immunity against pneumococcal challenge in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 173:380–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Triccas J. A., et al. 2007. Effects of DNA- and Mycobacterium bovis BCG-based delivery of the Flt3 ligand on protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 75:5368–5375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vadolas J., Davies J. K., Wright P. J., Strugnell R. A. 1995. Intranasal immunization with liposomes induces strong mucosal immune responses in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:969–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Ginkel F. W., Jackson R. J., Yuki Y., McGhee J. R. 2000. Cutting edge: the mucosal adjuvant cholera toxin redirects vaccine proteins into olfactory tissues. J. Immunol. 165:4778–4782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vitharsson G., Jonsdottir I., Jonsson S., Valdimarsson H. 1994. Opsonization and antibodies to capsular and cell wall polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 170:592–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu H. Y., Nahm M. H., Guo Y., Russell M. W., Briles D. E. 1997. Intranasal immunization of mice with PspA (pneumococcal surface protein A) can prevent intranasal carriage, pulmonary infection, and sepsis with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 175:839–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]