Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection is a grave concern in burn-injured patients. We investigated the efficacy of interleukin-18 (IL-18) treatment in postburn MRSA infection. Alternate-day injections of IL-18 into burn-injured C57BL/6 mice significantly increased their survival after MRSA infection and after methicillin-sensitive S. aureus infection. Although IL-18 treatment of burn-injured mice augmented natural IgM production before MRSA infection and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production after MRSA infection, neither IgM nor IFN-γ significantly contributed to the improvement in mouse survival. IL-18 treatment increased/restored the serum tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-17, IL-23, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP-2) levels, as well as the neutrophil count, after MRSA infection of burn-injured mice; it also improved impaired neutrophil functions, phagocytic activity, production of reactive oxygen species, and MRSA-killing activity. However, IL-18 treatment was ineffective against MRSA infection in both burn- and sham-injured neutropenic mice. Enhancement of neutrophil functions by IL-18 was also observed in vitro. Furthermore, when neutrophils from IL-18-treated burn-injured mice were adoptively transferred into nontreated burn-injured mice 2 days after MRSA challenge, survival of the recipient mice increased. NOD-SCID mice that have functionally intact neutrophils and macrophages (but not T, B, or NK cells) were substantially resistant to MRSA infection. IL-18 treatment increased the survival of NOD-SCID mice after burn injury and MRSA infection. An adoptive transfer of neutrophils using NOD-SCID mice also showed a beneficial effect of IL-18-activated neutrophils, similar to that seen in C57BL/6 mice. Thus, although neutrophil functions were impaired in burn-injured mice, IL-18 therapy markedly activated neutrophil functions, thereby increasing survival from postburn MRSA infection.

INTRODUCTION

Host defense against bacterial infections is severely impaired after burn injury, resulting in a high morbidity and mortality of postburn infections (11, 34). We previously demonstrated that burn injury impairs gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-mediated cellular immunity after Escherichia coli challenge in mice, and that interleukin-18 (IL-18) treatment restores the IFN-γ production, thereby improving the survival of burn-injured mice after E. coli infection (1, 22). However, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, not E. coli, are the most common bacteria in postburn infections (11, 34). In contrast to the response to E. coli infection, burn-injured mice retain IFN-γ production against P. aeruginosa infection (23). Nevertheless, they also show poor survival because natural IgM production, which is crucial for preventing P. aeruginosa infection, is suppressed in the mice after burn injury. Interestingly, IL-18 treatment following burn injury also restores the natural IgM production in the liver, thereby improving mouse survival from postburn P. aeruginosa infection (23). IL-18 treatment might thus effectively augment both IFN-γ-mediated cellular and IgM-mediated humoral immunities.

MRSA strains have been detected in approximately 40% of burn wound isolates (11). Moreover, the recent appearance of MRSA strains indicates that they are resistant not only to methicillin but also to other antibiotics such as vancomycin, which is one of the last-resort drugs. The increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant strains raises the specter of untreatable staphylococcal infections, and a novel therapeutic strategy different from antibiotic treatment is required (38).

Neutrophils play an essential role in the host defense against bacteria including S. aureus. Patients who are neutropenic or who have congenital or acquired defects in neutrophil function are susceptible to bacteria infections (16). Nevertheless, some investigators have pointed out the possibility that MRSA may elude a neutrophil-mediated host defense (41). Neutrophils are capable of chemotaxis toward mediators present at the infection site, and their principal roles in inflammatory and immune responses are phagocytosis and killing of bacteria via generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and release of proteolytic enzymes (9, 27). Many investigators have reported neutrophil dysfunctions in burn-injured patients (4, 10, 39), which may contribute to the increased susceptibility to bacterial infections following burn injury (30). Although several investigators recently demonstrated that IL-18 may activate neutrophil function (13, 28, 32, 33), little is known about how such IL-18-activated neutrophils protect mice from bacterial infections in vivo.

In the present study, we found that repeated exogenous IL-18 injections to burn-injured mice strongly activated/restored neutrophil functions, thereby improving survival of mice after MRSA infection. The present findings indicate that IL-18 therapy can be a potent therapeutic tool for postburn MRSA infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board for the Care of Animal Subjects at the National Defense Medical College, Japan.

Mice and burn injury.

Male C57BL/6 mice were studied (8 weeks old, 20 g; Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan). NOD-SCID (nonobese diabetic, severe combined immunodeficiency) mice (8 weeks old, 20 g; Charles River, Inc., Yokohama, Japan) were also used. As we previously described (1, 22, 23), mice were anesthetized using an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with pentobarbital (1 mg/mouse; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Once the mice were fully anesthetized, the dorsa were shaved, and the mice were placed in a plastic mold that exposed 20% of their total body surface area. The mice were then subjected to full-thickness burn injury by pressing a heated brass blade to the skin. Immediately after burn injury, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1 ml/mouse) was administered i.p. for fluid resuscitation. Sham mice only had their backs shaved and received no burn injury.

MRSA, MSSA, and reagents.

MRSA isolated from the clinical specimens of a patient in the National Defense Medical College Hospital was used. MRSA was grown on a brain heart infusion agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) supplemented with oxacillin for 48 h at 37 °C under aerobic conditions. S. aureus 209P (ATCC 6538P), a well-characterized methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strain, was from our laboratory collection. Mouse recombinant IL-18 (MBL, Nagoya, Japan), mouse IgM (PP50; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) collected from normal mouse serum, and anti-IFN-γ antibody ([Ab] R4-6A2, rat IgG1; IBL, Gunma, Japan) were used. Fluoresbrite YG (equivalent to fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]) carboxylate microspheres (750-nm diameter [Polysciences Europe, Eppelheim, Germany]; here called FITC-microspheres) and aminophenyl fluorescein (APF; Daiichi Pure Chemicals Co., Tokyo, Japan), which is a fluorescent reagent for the detection of highly reactive oxygen species (36), were also used.

Bacterial challenge and the collection of blood samples.

C57BL/6 mice were given an intravenous (i.v.) inoculation with 5 × 107 CFU of MRSA or MSSA 5 days after either burn or sham injury. Blood samples were obtained from the retro-orbital plexus of the mice, and then the sera were stored at −80 °C until assay. NOD-SCID mice were also inoculated i.v. with 5 × 107 CFU of MRSA 5 days after burn or sham injury.

IL-18 treatment (alternate-day injections), IgM injection, neutralization of IFN-γ, and depletion of NK/NKT cells.

IL-18 treatment was performed by i.p. injection (0.1 μg in 0.5 ml of PBS) on alternate days for 5 days after burn injury, namely, before MRSA or MSSA inoculation (1, 3, and 5 days after injury). This IL-18 treatment was also continued for up to 14 days after the inoculation (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 days after inoculation). Sham treatment was injection with PBS (0.5 ml) in the same manner as the IL-18 treatment. IgM injection (350 μg in 0.5 ml of PBS) or control PBS injection to burn-injured mice was intraperitoneal 1 h before MRSA inoculation. To neutralize IFN-γ, IL-18-treated burn-injured mice were injected i.v. with anti-IFN-γ Ab (500 μg/mouse) or isotype rat IgG1 (500 μg/mouse; Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany) 1 h before MRSA inoculation. To deplete NK1.1-positive (NK1.1+) cells (NK and NKT cells), IL-18-treated burn-injured mice were injected i.v. with anti-NK1.1 Ab (PK136; 200 μg/mouse) twice, at 3 days before and after burn injury, as we previously described (23).

Neutropenic mouse model.

Burn- or sham-injured mice were injected i.p. with anti-Ly-6G Ab (RB6-8C5; 200 μg/mouse) twice, at 1 day before and after MRSA inoculation, to induce a neutropenic condition. Control mice were similarly injected i.p. with isotype rat IgG2b (200 μg/mouse; MBL). In the sham-injured neutropenic mouse model, 5 × 107 CFU of MRSA was inoculated i.v. into the mice in each group. In the burn-injured neutropenic mouse model, 1 × 107 CFU of MRSA was inoculated i.v. in each group. IL-18/PBS treatment was similarly performed as described above.

Isolation of neutrophils or bone marrow cells.

As previously described (24, 29), a blood sample was drawn into a heparinized syringe from the abdominal inferior vena cava under lethal ether anesthesia. Leukocytes were isolated by dextran sedimentation. Thereafter, neutrophils were separated from mononuclear cells by centrifugation using Pancoll for mouse (PAN Biotech GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany), followed by hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes. The resultant cells contained nearly 90% neutrophils, as assessed by microscopy with Wright-Giemsa staining. Isolation of bone marrow cells was also performed as previously described (23). Under deep anesthesia with ether, mice were euthanized to remove their femurs. Bone marrow cells were obtained by injecting 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-RPMI 1640 medium into the femurs using a 1-ml syringe with a 26-gauge needle and then treating the cells with a red blood cell lysing solution.

In vitro IL-18 stimulation to neutrophils.

Neutrophils were obtained from the mice 5 days after burn or sham injury and then were incubated with 5 ng/ml IL-18 for 2 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Determination of microsphere phagocytosis by neutrophils.

Neutrophils were incubated with FITC-microspheres (1 × 108/ml) in 200 ml of 10% FBS-RPMI 1640 medium for 20 min in 5% CO2 at 37°C. After neutrophils were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse Gr-1 monoclonal antibody ([MAb] eBioscience, San Diego, CA), phagocytosis of FITC-microspheres by Gr-1+ neutrophils was analyzed using an Epics XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Miami, FL). FITC fluorescent intensity is dependent on the number of ingested microspheres (14). Peaks of the histogram correspond to neutrophils that contain no ingested microspheres or one (peak 1), two (peak 2), or more (peak ≥3) microspheres, as shown in Fig. 4A.

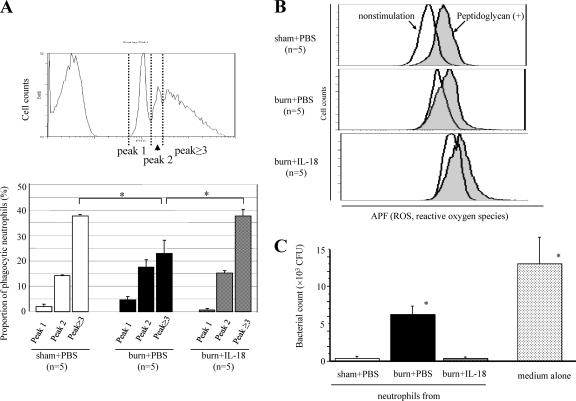

Fig. 4.

(A) The effect of IL-18 treatment on phagocytic activity of mouse neutrophils after MRSA inoculation. Neutrophils were obtained from burn-injured, sham, and IL-18-treated burn-injured mice 3 days after MRSA inoculation to examine their microsphere-phagocytic activity. The percentage of each peak is shown for the three mouse groups in the lower panel. *, P < 0.01. (B) The effect of IL-18 treatment on ROS production by neutrophils after MRSA inoculation. Neutrophils were obtained from the mice 3 days after MRSA inoculation. ROS production by nonstimulated and peptidoglycan-stimulated neutrophils was examined. Data shown are representative of each group. (C) The effect of IL-18 treatment on MRSA-killing activity of neutrophils after MRSA inoculation. Neutrophils were obtained from the mice 3 days after MRSA inoculation and then cultured with MRSA for 6 h. Thereafter, the number of viable bacteria was counted. Data are from three individual experiments with 3 to 5 mice per group. Data in panels A and C are the means ± SE. *, P < 0.01 versus other groups.

Determination of reactive oxygen species production by neutrophils.

Neutrophils were incubated with 1 μl of APF for 20 min in 5% CO2 at 37°C. After incubation with Fc blocker (2.4 G2; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) to prevent nonspecific binding, neutrophils were stained with PE-conjugated Gr-1 MAb. Then, ROS production by Gr-1+ neutrophils, as assessed by FITC fluorescent intensity, was analyzed using an Epics XL flow cytometer. Neutrophils were also stimulated with 10 μg/ml peptidoglycan from S. aureus (Toll-like receptor 2 stimulator) (Sigma-Aldrich) or 1 × 105 CFU of MRSA during APF incubation.

Determination of MRSA-killing activity by neutrophils.

Neutrophils (5 × 105/200 μl of medium without antibiotic) were cultured with 1 × 103 CFU of MRSA for 6 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Thereafter, culture medium was serially diluted 10-fold with PBS, placed using a spiral platter on brain heart infusion agar plates, and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The number of viable bacteria was then counted according to the observed colonies on the agar plates.

Analysis of IL-18R or CD11b expression on neutrophils and Gr-1 expression on bone marrow cells.

After incubation with Fc blocker, neutrophils were incubated with anti-mouse IL-18 receptor α (IL-18Rα) Ab (goat IgG) (R&D Systems, Inc., Abingdon, England) for 15 min and stained with PE-conjugated anti-goat IgG (R&D Systems) and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse Gr-1 MAb (eBioscience). Expression of IL-18 receptor on Gr-1+ neutrophils was analyzed using an Epics XL flow cytometer. Neutrophils were also stained with PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b MAb (eBioscience) and FITC-conjugated Gr-1 MAb. Then, CD11b expression on Gr-1+ neutrophils was analyzed. Bone marrow cells were stained with PE-conjugated Gr-1 MAb after incubation with Fc blocker, and their Gr-1 expression levels were analyzed. Neutrophils differentiate mainly in the bone marrow and can be classified into populations of myelocytes (and metamyelocytes) expressing low levels of Gr-1 (Gr-1dim) and mature neutrophils expressing high levels of Gr-1 (Gr-1bright), that is, Gr-1+ neutrophils (see Fig. 6C) (12).

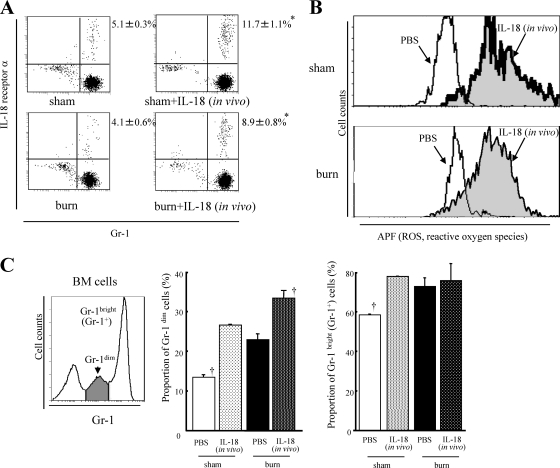

Fig. 6.

(A) The effect of IL-18 treatment on the expression of IL-18 receptor α on neutrophils from the burn- or sham-injured mice. Burn- or sham-injured mice were treated with IL-18/PBS. Neutrophils were obtained from the mice 5 days after injury. The percentages for the upper right quadrants represent IL-18 receptor α-expressing neutrophils. (B) The effect of IL-18 treatment on ROS production in neutrophils. Neutrophils obtained from the treated mice 5 days after burn/sham injury were in vitro stimulated with MRSA. (C) The effect of IL-18 treatment on neutrophil maturation/differentiation in the bone marrow (BM). Bone marrow cells were obtained from the treated mice 5 days after burn/sham injury. All data are pooled from three individual experiments with 3 to 5 mice per group. In panels A and B, representative data are shown for each group. Data are the means ± SE. *, P < 0.01 versus the respective burn and sham groups; †, P < 0.01 versus other groups.

Measurements of neutrophil count and serum cytokine and IgM levels.

Blood leukocytes were counted using a PEC-170 hematology analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). The neutrophil percentage in the leukocytes was also determined using a smear stained by Wright-Giemsa. Neutrophil count was then determined as the leukocyte count multiplied by the neutrophil percentage (23). Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-17, IL-23, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), and IgM were measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (for IL-23, R&D Systems; for IgM, Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX; for all others, Endogen, Woburn, MA).

Viable bacterial counts in the blood, lung, and liver.

Blood samples (1 ml) were aseptically drawn from the abdominal vena cava. The liver and lungs (bilateral) were also aseptically removed and homogenized into a PBS suspension. The bacterial suspensions were serially diluted 10-fold with PBS, placed using a spiral platter on brain heart infusion agar plates, and incubated at 37°C for 24 h to count the number of viable bacteria.

Adoptive transfer of neutrophils to the MRSA-inoculated burned mice.

Adoptive transfer of neutrophils was performed using C57BL/6 mice or NOD-SCID mice. Blood samples were obtained from the abdominal inferior vena cava in burn-injured, sham, and IL-18-treated burn-injured mice 2 days after MRSA inoculation. Subsequently, neutrophils were isolated from the blood samples in each mouse group and were injected i.v. into recipient burn-injured mice (1 × 107 neutrophils in 0.2 ml of PBS) at 2 days after their MRSA inoculation.

Statistical analysis.

The data are presented as mean values ± standard errors (SE). Statistical analyses were performed using an iMac computer (Apple, Cupertino, CA) and the Stat View, version 4.02J, software package (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). The survival rates were compared using a Wilcoxon rank test, and any other statistical evaluations were compared using standard one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferoni posthoc test. A P value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

RESULTS

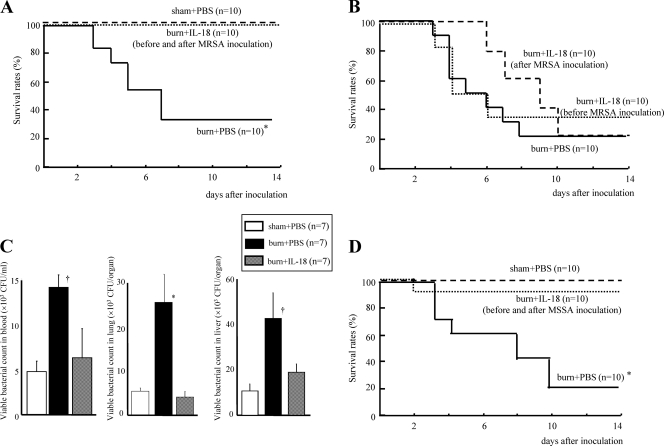

IL-18 treatment before and after MRSA inoculation increases the survival from postburn infection.

Although burn injury greatly decreased mouse survival after MRSA inoculation, IL-18 given both before and after MRSA inoculation dramatically improved the survival of burn-injured mice (100% survival) (Fig. 1A). However, IL-18 treatment either only before or only after MRSA inoculation did not improve their survival (Fig. 1B). IL-18 treatment given before and after MRSA inoculation significantly decreased the number of viable bacteria in the blood, lungs, and liver of the burn-injured mice 3 days after MRSA infection (Fig. 1C). IL-18 treatment was also significantly effective against MSSA infection in the burn-injured mice (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

(A) The effect of IL-18 treatment on the survival of burn-injured mice after MRSA inoculation. The burn- or sham-injured mice were treated with IL-18 or PBS before and after MRSA inoculation and were inoculated with MRSA 5 days after injury. (B) The effect of IL-18 treatment either only before or only after MRSA inoculation. Burn-injured mice were treated with IL-18 or PBS either only before MRSA inoculation or only after inoculation. MRSA inoculation was 5 days after injury. (C) The effect of IL-18 treatment on the number of viable bacteria in the blood, lungs, and liver in the MRSA-inoculated burn-injured mice. The blood, lungs, and liver were obtained from the IL-18/PBS-treated mice 72 h after MRSA inoculation. Data are the means ± SE. (D) The effect of IL-18 treatment on the survival of burn-injured mice after MSSA inoculation. The injured mice were treated with IL-18/PBS before and after MSSA inoculation that was performed 5 days after injury. *, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.05 (versus other groups).

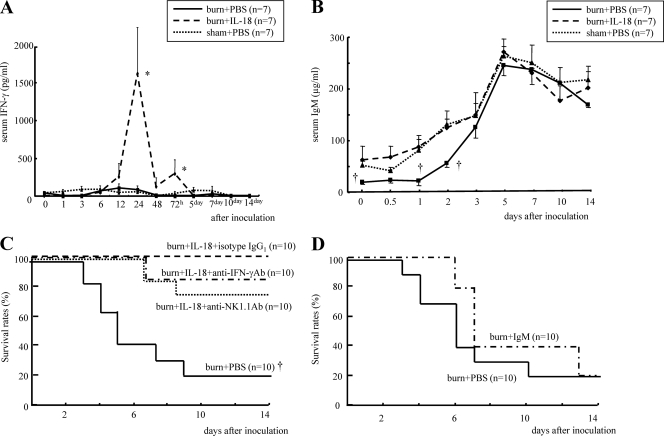

Neither IL-18-induced IFN-γ nor IgM improves survival of postburn MRSA infection.

IL-18 treatment remarkably increased serum IFN-γ levels after MRSA inoculation in burn-injured mice although neither burn- nor sham-injured mice showed significant IFN-γ elevations (Fig. 2 A). IL-18 treatment also significantly restored serum IgM levels in burn-injured mice until 2 days after MRSA inoculation although no difference was observed in the peak of serum IgM at 5 days among three groups (Fig. 2B). Neither neutralization of IFN-γ nor depletion of NK1.1+ cells (NK and NKT cells), which are the main IFN-γ-producing cells, significantly affected survival after MRSA inoculation of IL-18-treated burn-injured mice (Fig. 2C). Injection with IgM collected from normal mouse serum also did not significantly affect the survival of the burn-injured mice (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

The effect of IL-18 treatment on serum IFN-γ (A) and IgM (B) levels after MRSA inoculation in burn-injured mice. Mice were treated with IL-18 or PBS after burn/sham injury and then inoculated with MRSA 5 days after injury. (C) The effect of neutralization of IFN-γ or depletion of NK/NKT cells on survival after MRSA inoculation in IL-18-treated burn-injured mice. Such mice were treated with anti-IFN-γ neutralizing Ab, anti-NK1.1 Ab, or rat IgG1, as described in Materials and Methods. These mice were inoculated with MRSA 5 days after burn injury. PBS-treated burn-injured mice were also similarly inoculated with MRSA. (D) The effect of IgM injection on the survival of burn-injured mice after MRSA inoculation. Burn-injured mice were pretreated with IgM or PBS injection 1 h before MRSA inoculation that was performed 5 days after injury. Data in panels A and B are the means ± SE. *, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.05 (versus other groups).

IL-18 treatment effect on neutrophil counts and serum cytokine levels.

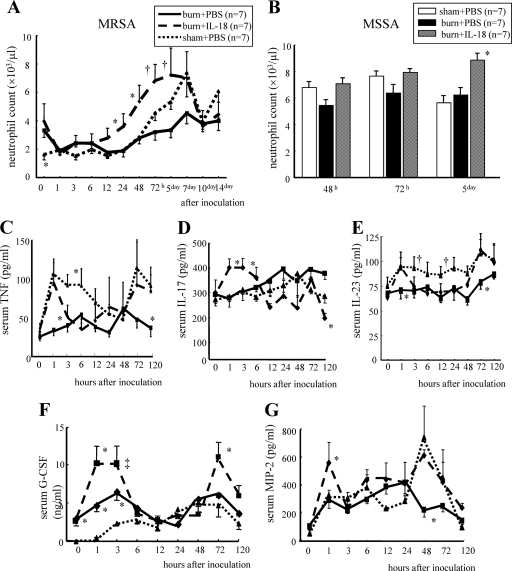

IL-18 treatment significantly increased neutrophil counts in response to MRSA inoculation in burn-injured mice (Fig. 3 A). IL-18 treatment also increased neutrophil counts 5 days after MSSA inoculation (Fig. 3B), suggesting an effect of IL-18 on neutrophils similar to that of MRSA infection. Regarding MRSA infection, IL-18 treatment restored the elevation of serum TNF levels 1 h after inoculation in burn-injured mice (Fig. 3C). It also significantly increased serum IL-17 levels at 1 to 3 h in burn-injured mice although burn injury itself did not significantly affect the IL-17 level (Fig. 3D). IL-18 treatment elevated serum IL-23 levels at 1 h and 3 days in burn-injured mice although burn-injured mice showed lower serum IL-23 levels after MRSA inoculation (Fig. 3E). Burn-injured mice showed significantly higher serum G-CSF levels than sham mice both before MRSA inoculation and 1 to 3 h after inoculation, while IL-18 treatment further increased the G-CSF levels 1 h and 3 days after inoculation in burn-injured mice (Fig. 3F). IL-18 treatment significantly increased serum MIP-2 levels at 1 h and also restored its peak at 2 days after infection in burn-injured mice (Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

The effect of IL-18 treatment on neutrophil count after MRSA (A) or MSSA (B) inoculation in burn-injured mice and also on the serum TNF (C), IL-17 (D), IL-23 (E), G-CSF (F), and MIP-2 (G) levels after MRSA inoculation. The burn-injured, sham, and IL-18-treated burn-injured mice were inoculated with MRSA or MSSA 5 days after injury. Data are the means ± SE. *, P < 0.05 versus other groups; †, P < 0.05 versus PBS-treated burn-injured group; ‡, P < 0.01 versus PBS-treated sham group.

IL-18 treatment restores phagocytosis and MRSA-killing activities by neutrophils.

Although burn injury significantly decreased the proportion of neutrophils having potent phagocytic activities (Fig. 4 A, peak ≥3) 3 days after MRSA inoculation, IL-18 treatment significantly restored these activities of neutrophils in burn-injured mice (Fig. 4A). Burn injury increased ROS production by neutrophils 3 days after MRSA inoculation both under nonstimulative and peptidoglycan-stimulative conditions, while IL-18 treatment following burn injury further enhanced ROS production by neutrophils under both conditions (Fig. 4B). Although burn injury markedly impaired the MRSA-killing activity of neutrophils 3 days after MRSA inoculation, IL-18 treatment significantly restored the killing activity of neutrophils in burn-injured mice (Fig. 4C).

IL-18 treatment against MRSA infection in neutropenic mice.

Anti-Ly-6G Ab-treated mice showed a severe neutropenia 12 h after inoculation with 5 × 107 CFU of MRSA relative to the isotype IgG2b-treated mice (circulating neutrophil count, 86 ± 19 versus 1,511 ± 179/μl; P < 0.01), and these neutropenic mice were markedly susceptible to MRSA infection (Fig. 5 A). However, IL-18 treatment did not increase their survival (Fig. 5A). Next, we inoculated burn-injured mice with 1 × 107 CFU of MRSA and then confirmed that their survival rates were 70% (Fig. 5B). Nevertheless, no neutropenic mice receiving burn injury survived this dose of MRSA (Fig. 5B). IL-18 treatment was also ineffective against this postburn MRSA infection in neutropenic mice (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

The effect of IL-18 treatment on survival after MRSA inoculation in sham-injured or burn-injured neutropenic mice. (A) A neutropenic mouse model was made using anti-Ly-6G Ab, as described in Materials and Methods. These mice received IL-18 or PBS treatment following sham injury and were then inoculated with 5 × 107 CFU of MRSA 5 days after injury. (B) Neutropenic mice also received IL-18/PBS treatment after burn injury and then were inoculated with 1 × 107 CFU of MRSA 5 days after injury. *, P < 0.01 versus other groups.

Multiple IL-18 injections significantly enhance other neutrophil functions.

A few neutrophils (4 to 5%) in both burn- and sham-injured mice 5 days after injury expressed IL-18 receptor α; IL-18 treatment increased the expression in both groups of mice (Fig. 6 A). These increases were not large but were statistically significant (sham-injured mice, 5.1% to 11.7%; burn-injured mice, 4.1% to 8.9%). Although burn injury reduced the microsphere phagocytic activity of neutrophils, multiple IL-18 injections remarkably augmented neutrophil phagocytosis in not only sham- but also burn-injured mice (data not shown). This phagocytic activity of mouse neutrophils was most severely impaired 5 days after burn injury relative to that at 1 or 7 days (data not shown). Consistently, the burn-injured mice had the worst survival rate when they were inoculated with MRSA 5 days after burn injury (data not shown). Neutrophils from burn-injured mice 5 days after injury increased ROS production by in vitro MRSA stimulation relative to those from sham mice, while multiple IL-18 injections further enhanced ROS production by neutrophils in both burn- and sham-injured mice (Fig. 6B). Although burn injury reduced MRSA-killing activity of neutrophils 5 days after injury, multiple IL-18 injections markedly augmented that activity in both burn- and sham-injured mice (data not shown). Multiple IL-18 injections significantly increased the proportions of both Gr-1dim myelocytes and Gr-1bright neutrophils in the bone marrow of sham mice (Fig. 6C). Burn injury also increased both Gr-1dim and Gr-1bright cells in the mouse bone marrow, while multiple IL-18 injections further increased Gr-1dim myelocytes but not Gr-1bright neutrophils in burn-injured mice (Fig. 6C), suggesting that IL-18 treatment affects Gr-1dim myelocytes in the bone marrow even after burn injury.

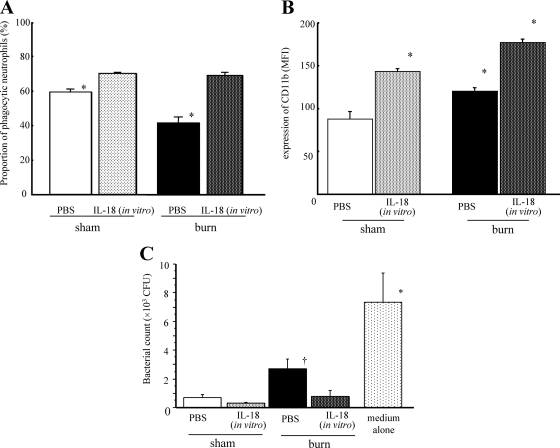

In vitro stimulation with IL-18 activates neutrophil functions.

In vitro IL-18 stimulation also markedly restored/augmented microsphere-phagocytic activity in neutrophils from both burn- and sham-injured mice 5 days after injury (Fig. 7 A) and upregulated ROS production in neutrophils in both groups of mice (data not shown), suggesting direct effects of IL-18 on neutrophils in vitro. Burn injury upregulated CD11b expression on mouse neutrophils (Fig. 7B), while in vitro IL-18 stimulation significantly enhanced CD11b expression on neutrophils in both burn- and sham-injured mice (Fig. 7B). Although burn injury reduced the MRSA-killing activity of neutrophils, in vitro IL-18 stimulation also augmented the killing activity of neutrophils from the burn-injured mice (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

The effect of in vitro IL-18 stimulation on neutrophil functions in burn- or sham-injured mice. Neutrophils obtained from the mice 5 days after burn/sham injury were incubated with IL-18/PBS for 2 h. Thereafter, the proportion of neutrophils with potent phagocytic activity (peak ≥ 3) (Fig. 4A) (A), CD11b expression levels (B), and MRSA-killing activity (6-h assay) (C) were examined. All data are pooled from three individual experiments with 3 to 5 mice per group. Data are the means ± SE. *, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.05 (versus other groups).

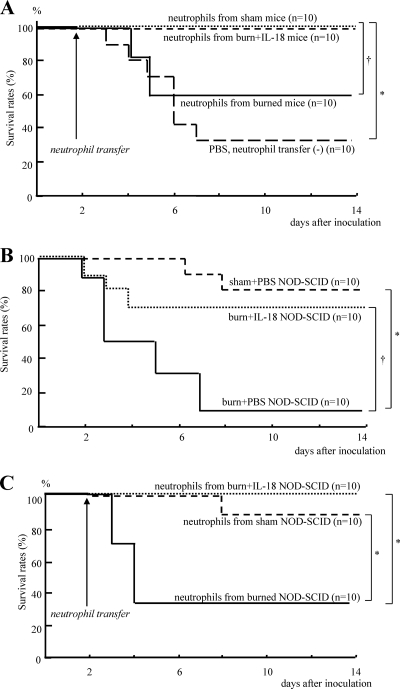

Adoptive transfer of neutrophils in C57BL/6 mice.

Neutrophils were obtained from the burn-injured, sham, and IL-18-treated burn-injured mice 2 days after MRSA inoculation. Thereafter, neutrophils (1 × 107) were transferred into recipient burn-injured mice 2 days after their MRSA inoculation. The transfer of neutrophils from IL-18-treated burn-injured mice, as well as from sham mice, greatly increased the survival of recipient burn-injured mice relative to transfer from untreated burn-injured mice (Fig. 8 A).

Fig. 8.

(A) The effect of adoptive transfer of neutrophils on survival after MRSA inoculation of the burn-injured C57BL/6 mice. Neutrophils were obtained from the burn-injured, sham, and IL-18-treated burn-injured mice 2 days after MRSA inoculation and then were transferred to recipient burn-injured mice 2 days after their MRSA infection. Similarly, PBS was also administered alone to the recipient burn-injured mice. (B) The effect of IL-18 treatment on the survival of burn-injured NOD-SCID mice after MRSA inoculation. The burn- or sham-injured NOD-SCID mice were treated with IL-18/PBS before and after MRSA inoculation and were inoculated with MRSA 5 days after injury. (C) The effect of adoptive transfer of neutrophils on survival after MRSA inoculation of the burn-injured NOD-SCID mice. Adoptive transfer of neutrophils was similarly performed using NOD-SCID mice, as described for panel A. *, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.05.

IL-18 treatment against postburn MRSA infection in NOD-SCID mice and adoptive transfer of neutrophils.

Sham-injured NOD-SCID mice that lack T and B cells and have functionally deficient NK cells (but intact macrophages and neutrophils) (37) have resistance to 5 × 107 CFU of MRSA infection (80% survival) (Fig. 8B). Although burn injury significantly decreased the survival of NOD-SCID mice after MRSA infection, IL-18 treatment improved their survival (Fig. 8B).

Neutrophils were similarly obtained from burn-injured, sham-treated, and IL-18-treated burn-injured NOD-SCID mice and were then transferred into recipient burn-injured NOD-SCID mice 2 days after MRSA inoculation. Such transfer of neutrophils from IL-18-treated burn-injured NOD-SCID mice, as well as from sham-treated NOD-SCID mice, significantly increased the survival of recipient burn-injured NOD-SCID mice (Fig. 8C).

DISCUSSION

Our previous and present studies have demonstrated that multiple IL-18 injections to mice upregulate the IFN-γ-mediated cellular immune response, IgM-mediated humoral immune response, and neutrophil-mediated immune response (1, 22, 23, 25). IL-18 is thus a multipotential and pleiotropic cytokine. Burn injury renders the host severely immunocompromised. In burn-injured mice, IFN-γ production by NK cells, natural IgM production by hepatic B1 cells, and phagocytic activity by neutrophils are all impaired (1, 22, 23, 25), resulting in a susceptibility to bacterial infections.

Neither IFN-γ-mediated cellular immunity nor IgM-mediated humoral immunity augmented by IL-18 therapy was effective against postburn MRSA infection (Fig. 2C and D) although such factors induced by IL-18 are crucial for the defense of immunocompromised hosts (for example, burn-injured or splenectomized) against bacterial infections by P. aeruginosa, E. coli, or Streptococcus pneumoniae (1, 22, 23, 25). Even though IL-18 treatment might increase IFN-γ and IgM production, it could not improve the outcome of a mouse MRSA infection. However, it is noteworthy that IL-18 enhanced neutrophil functions, including bactericidal activity, and markedly increased mouse survival following postburn MRSA infection. Furthermore, IL-18-activated neutrophils directly inhibited MRSA infection, as evidenced by adoptive transfer experiments (Fig. 8A and C). IL-18 therapy can thus be a potent therapeutic tool against various kinds of bacterial infections following burn injury.

MRSA is a persistent human pathogen that has great adaptability for developing antibiotic resistance. It is also a serious endemic pathogen in many hospitals and burn units, accounting for significant hospital morbidity and mortality (8, 34). MRSA infection in burn-injured mice was indeed more resistant to IL-18 therapy than P. aeruginosa or E. coli infection. IL-18 therapy applied only before MRSA inoculation did not improve mouse survival of postburn MRSA infection (Fig. 1B), whereas such IL-18 therapy before infection significantly improved the survival of postburn infections with either P. aeruginosa or E. coli inoculation (1, 22, 23). Repeated IL-18 injections both before and after bacterial inoculation were required to improve mouse survival of postburn MRSA infection (Fig. 1A). Such pernicious biological characteristics may be one of the major reasons why MRSA causes widespread and refractory infections in humans.

Recent studies have reported a novel IL-17-producing T helper subset distinct from Th1 and Th2 lineages; these are termed Th17 cells (2, 43). IL-17 can induce granulopoiesis via G-CSF production (2, 35), and it induces neutrophil recruitment via C-X-C chemokines, such as MIP-2, in the organs (26). IL-17 is also involved in TNF production from macrophages (15). IL-23 plays important roles to maintain Th17 function although it is not directly involved in Th17 differentiation by itself (17). These findings are consistent with the results in this study. IL-18 may have a potential to regulate not only Th1 and Th2 responses but also other immune responses (including Th17), all of which are important for host defense against microbial infections. However, IL-18 is a potent inducer of IFN-γ (in the presence of IL-12) that can inhibit IL-17 production (43). In line with this, IL-18 is likely to have an inhibitory effect on Th17 response. Further study is required to clarify how IL-18 affects the Th17 response. Macrophages have a potent capability to produce TNF, IL-23, G-CSF, and MIP-2 within a few hours in response to bacterial stimuli, and they also express an IL-18 receptor on their surfaces (19, 31), indicating that IL-18 treatment may stimulate macrophages to produce these cytokines in response to MRSA inoculation.

A burn injury stimulated mouse neutrophils to enhance ROS production (Fig. 6B) and CD11b expression (Fig. 7B). It also augmented neutrophil maturation/differentiation in mouse bone marrow (Fig. 6C). Burn injury thus activates neutrophils, leading to remote tissue damage and multiorgan dysfunctions (5, 42). Activated neutrophils are involved in the occurrence of acute lung injury following burn injury (3). We previously demonstrated that burn injury augments superoxide production by neutrophils (29) and also demonstrated that activated neutrophils cause acute lung injury (20, 21). However, burn injury also reduced the phagocytic and bactericidal activities of neutrophils (Fig. 7A and C). Thus, burn injury might abrogate beneficial functions of neutrophils that are crucial to eliminating bacterial pathogens and might induce functionally abnormal activation of neutrophils, resulting in organ damage/dysfunction. However, it is noteworthy that IL-18 treatment restored neutrophil phagocytic and MRSA-killing activities in burn-injured mice (Fig. 7A and C) and further upregulated ROS production (Fig. 6B). IL-18 might thus induce functionally effective activation in neutrophils.

NOD-SCID mice have functionally intact neutrophils and macrophages but do not have T, B, or intact NK cells. These mice were substantially resistant to MRSA infection (Fig. 8B) while neutropenic mice were extremely susceptible (Fig. 5A), suggesting that neutrophils play a crucial role against MRSA infection. Interestingly, IL-18 therapy was effective against postburn MRSA infection in the NOD-SCID mice (Fig. 8B) while it was ineffective in the neutropenic mice (Fig. 5B). These findings suggest that neutrophils activated by IL-18 therapy contribute to the defense against the postburn MRSA infection in mice. Furthermore, adoptive transfer experiments of neutrophils using both C57BL/6 mice and NOD-SCID mice (Fig. 8A and C) demonstrated that IL-18-activated neutrophils indeed improved survival after postburn MRSA infection. Macrophages as well as neutrophils might play an important role against postburn MRSA infection. Katakura et al. have demonstrated the crucial role of macrophages against postburn MRSA infection although these investigators have also described a certain role of neutrophils against this infection (18). Further study of the role of IL-18-stimulated macrophages against postburn MRSA infection is needed.

Although circulating neutrophils are usually short-lived, their life span increases significantly once they migrate out of the circulation and into the inflammatory tissue sites, where they encounter various proinflammatory mediators (6, 7, 40). In the present study, neutrophils might be substantially activated by various proinflammatory mediators at the time of their adoptive transfer because these neutrophils were obtained from the MRSA-inoculated mice, especially from IL-18-treated mice. After adoptive transfer, activated neutrophils presumably migrate into infectious sites in the recipient mice and also might encounter additional proinflammatory mediators there because the recipient mice were inoculated with MRSA 2 days before. Therefore, transferred neutrophils may increase their life span in the recipient mice and eliminate MRSA, thereby increasing the survival of recipient mice, in particular, when neutrophils from sham or IL-18-treated burn-injured mice are transferred (Fig. 8A and C).

Taking these results together, IL-18 might enhance not only cellular immunity (IFN-γ) and humoral immunity (IgM) but also neutrophil function, and it may confer resistance to the immunocompromised hosts against various bacterial infections, including E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. pneumoniae, and MRSA (1, 22, 23, 25).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ami K., et al. 2002. IFN-gamma production from liver mononuclear cells of mice in burn injury as well as in postburn bacterial infection models and the therapeutic effect of IL-18. J. Immunol. 169:4437–4442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bi Y., Liu G., Yang R. 2007. Th17 cell induction and immune regulatory effects. J. Cell. Physiol. 211:273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Craig A., Mai J., Cai S., Jeyaseelan S. 2009. Neutrophil recruitment to the lungs during bacterial pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 77:568–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davis J. M., Dineen P., Gallin J. I. 1980. Neutrophil degranulation and abnormal chemotaxis after thermal injury. J. Immunol. 124:1467–1471 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Demling R. H. 1985. Burns. N. Engl. J. Med. 313:1389–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dibbert B., et al. 1999. Cytokine-mediated Bax deficiency and consequent delayed neutrophil apoptosis: a general mechanism to accumulate effector cells in inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:13330–13335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elbim C., Estaquier J. 2010. Cytokines modulate neutrophil death. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 21:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haddadin A. S., Fappiano S. A., Lipsett P. A. 2002. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the intensive care unit. Postgrad. Med. J. 78:385–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hampton M. B., Kettle A. J., Winterbourn C. C. 1996. Involvement of superoxide and myeloperoxidase in oxygen-dependent killing of Staphylococcus aureus by neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 64:3512–3517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heck E. L., Browne L., Curreri P. W., Baxter C. R. 1975. Evaluation of leukocyte function in burned individuals by in vitro oxygen consumption. J. Trauma 15:486–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heggers J. P., et al. 1988. The epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a burn center. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 9:610–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hestdal K., et al. 1991. Characterization and regulation of RB6-8C5 antigen expression on murine bone marrow cells. J. Immunol. 147:22–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hirata J., et al. 2008. A role for IL-18 in human neutrophil apoptosis. Shock 30:628–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inatsu A., et al. 2009. Novel mechanism of C-reactive protein for enhancing mouse liver innate immunity. Hepatology 49:2044–2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jovanovic D. V., et al. 1998. IL-17 stimulates the production and expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-beta and TNF-alpha, by human macrophages. J. Immunol. 160:3513–3521 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanamaru A., Tatsumi Y. 2004. Microbiological data for patients with febrile neutropenia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39(Suppl. 1):S7–S10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kastelein R. A., Hunter C. A., Cua D. J. 2007. Discovery and biology of IL-23 and IL-27: related but functionally distinct regulators of inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25:221–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katakura T., Yoshida T., Kobayashi M., Herndon D. N., Suzuki F. 2005. Immunological control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in an immunodeficient murine model of thermal injuries. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 142:419–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kataoka T. R., Komazawa N., Oboki K., Morii E., Nakano T. 2005. Reduced expression of IL-12 receptor β2 and IL-18 receptor α genes in natural killer cells and macrophages derived from B6-mi/mi mice. Lab. Invest. 85:146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kinoshita M., Mochizuki H., Ono S. 1999. Pulmonary neutrophil accumulation following human endotoxemia. Chest 116:1709–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kinoshita M., Ono S., Mochizuki H. 2000. Neutrophils mediate acute lung injury in rabbits: role of neutrophil elastase. Eur. Surg. Res. 32:337–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kinoshita M., Seki S., Ono S., Shinomiya N., Hiraide H. 2004. Paradoxical effect of IL-18 therapy on the severe and mild Escherichia coli infections in burn-injured mice. Ann. Surg. 240:313–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kinoshita M., et al. 2006. Restoration of natural IgM production from liver B cells by exogenous IL-18 improves the survival of burn-injured mice infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Immunol. 177:4627–4635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kinoshita M., et al. 2005. Opposite effects of enhanced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production from Kupffer cells by gadolinium chloride on liver injury/mortality in endotoxemia of normal and partially hepatectomized mice. Shock 23:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuranaga N., et al. 2006. Interleukin-18 protects splenectomized mice from lethal Streptococcus pneumoniae sepsis independent of interferon-gamma by inducing IgM production. J. Infect. Dis. 194:993–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laan M., et al. 1999. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J. Immunol. 162:2347–2352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee A., Whyte M. K., Haslett C. 1993. Inhibition of apoptosis and prolongation of neutrophil functional longevity by inflammatory mediators. J. Leukoc. Biol. 54:283–288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leung B. P., et al. 2001. A role for IL-18 in neutrophil activation. J. Immunol. 167:2879–2886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Masuda Y., Kinoshita M., Ono S., Tsujimoto H., Mochizuki H. 2006. Diverse enhancement of superoxide production from Kupffer cells and neutrophils after burn injury or septicemia. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 38:25–32 [Google Scholar]

- 30. McEuen D. D., Gerber G. C., Blair P., Eurenius K. 1976. Granulocyte function and Pseudomonas burn wound infection. Infect. Immun. 14:399–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakanishi K., Yoshimoto T., Tsutsui H., Okamura H. 2001. Interleukin-18 regulates both Th1 and Th2 responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:423–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Netea M. G., et al. 2000. Neutralization of IL-18 reduces neutrophil tissue accumulation and protects mice against lethal Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium endotoxemia. J. Immunol. 164:2644–2649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rana S. N., Li X., Chaudry I. H., Bland K. I., Choudhry M. A. 2005. Inhibition of IL-18 reduces myeloperoxidase activity and prevents edema in intestine following alcohol and burn injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77:719–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ransjo U., Malm M., Hambraeus A., Artursson G., Hedlund A. 1989. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in two burn units: clinical significance and epidemiological control. J. Hosp. Infect. 13:355–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwarzenberger P., et al. 2000. Requirement of endogenous stem cell factor and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor for IL-17-mediated granulopoiesis. J. Immunol. 164:4783–4789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Setsukinai K., Urano Y., Kakinuma K., Majima H. J., Nagano T. 2003. Development of novel fluorescence probes that can reliably detect reactive oxygen species and distinguish specific species. J. Biol. Chem. 278:3170–3175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shultz L. D., Ishikawa F., Greiner D. L. 2007. Humanized mice in translational biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7:118–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sieradzki K., Roberts R. B., Haber S. W., Tomasz A. 1999. The development of vancomycin resistance in a patient with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Solomkin J. S., Nelson R. D., Chenoweth D. E., Solem L. D., Simmons R. L. 1984. Regulation of neutrophil migratory function in burn injury by complement activation products. Ann. Surg. 200:742–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taneja R., et al. 2004. Delayed neutrophil apoptosis in sepsis is associated with maintenance of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and reduced caspase-9 activity. Crit. Care Med. 32:1460–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tsuda Y., et al. 2004. Three different neutrophil subsets exhibited in mice with different susceptibilities to infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity 21:215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weiss S. J. 1989. Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N. Engl. J. Med. 320:365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wynn T. A. 2005. TH-17: a giant step from TH1 and TH2. Nat. Immunol. 6:1069–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]