Abstract

Introduction

Cocaine is a highly addictive drug of abuse for which there are currently no medications. In rats and mice d-cycloserine (DCS), a partial NMDA agonist, accelerates extinction of cocaine seeking behavior. Since cues delay extinction here, we evaluated the effects d-cycloserine in extinction with and without the presence of cues.

Methods

Two doses of DCS (15 and 30 mg/kg) were studied in C57 mice. Mice self-administered cocaine (1 mg/kg) for 2 weeks and then underwent a 20-day extinction period where DCS was administered i.p. immediately following each daily session. Extinction was conducted in some mice with the presence of cocaine-paired cues; while others were in the absence of these cues.

Results

DCS treated mice (either dose) showed significantly reduced lever pressing during extinction with cue exposures when compared with vehicle treated mice. Without cues, animals showed much lower levels of lever pressing but the differences between vehicle and DCS were not significant.

Conclusion

DCS accelerated extinction with the presence of cues, but there were no differences on extinction without cues as compared with vehicle. These findings are consistent with DCS disrupting the memory process associated with the cues. Since drug cues are significantly involved in relapse, these findings support research to assess the therapeutic potential of DCS in cocaine addiction.†

Keywords: D-cycloserine, NMDA, agonist, extinction, cocaine

INTRODUCTION

Several cocaine self-administration models have been developed in rodents to emulate cocaine abuse and addiction in humans (Koob et al., 2004; Koob and Bloom, 1988; Withers, 1995). These models assess various behaviors including conditioning, cocaine self-administration, escalation of cocaine self-administration, extinction, abstinence, and reinstatement or relapse.

The brain builds important associations between the environment and its consequences (appetitive or aversive), and this is typically studied using conditioned place preference (CPP) (Cunningham et al., 2006) or the use of stimulus cues during self-administration (Di Ciano and Everitt, 2004, 2005). Conditioned cues, such as light and tone, that have previously been paired with reward (e.g., food, sucrose, drugs), release dopamine (DA) in striatum, even in the absence of the reward itself (Crombag and Shaham, 2002; Hamlin et al., 2008). These associations can maintain behavior even without the presence of the reward, and are studied using extinction models that assess the time it takes for the drug seeking behavior to extinguish when the cue is no longer followed by the reward. During extinction, there is a progressive decline in the drug seeking behavior (lever responses). These diminished responses may reflect new learning that the cues no longer follow reward (Quirk et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2009). Extinction of an operant response consists of a three-phased learning process: acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval (Quirk, 2008). NMDA receptors play a crucial role in the consolidation phase of posttraining learning and extinction (McDonald et al., 2005; Santini et al., 2001; Suzuki, 2004) through prefrontal striatal pathways (Burgos-Robles et al., 2007; Quirk, 2006, 2008).

D-cycloserine (DCS) is a partial NMDA receptor agonist (Klodzińska and Chojnacka-Wójcik, 2000) that has been shown to accelerate fear extinction through new memory consolidation (Walker et al., 2002). DCS’s effectiveness in promoting extinction of conditioned fear was extended to humans with a conditioned response experiment, including repeated audiovisual stimulus followed by electrical shock (Kalisch et al., 2008). DCS has shown clinical benefits in treating acrophobia (Ressler et al., 2004), obsessive compulsive disorder (Kushner et al., 2007) and social anxiety disorder (Hofmann et al., 2006).

Recently, studies found DCS to be similarly effective in the extinction of cocaine CPP in rats, where DCS treated rats lost preference for the cocaine paired environment in less than half the time compared with vehicle (Botreau, et al., 2006). Similarly in mice, preference for the cocaine paired box was extinguished by the third day of extinction with DCS compared with the sixth day for the vehicle group (Thanos et al., 2009). In these previous studies, DCS (15 and 30 mg/kg) facilitated extinction to cocaine CPP, with cues present.

Previous studies have shown that DCS facilitates stimulus-driven learning at doses of 0.3–10 mg/kg for rats (Monahan et al., 1989) and at slightly higher doses (10–20 mg/kg) for mice (Flood et al., 1992). For cocaine CPP extinction, DCS was shown to be effective at 15 mg/kg for rats (Botreau et al., 2006), and mice (Thanos et al, 2009) as well as at a higher dose of 30 mg/kg in mice (Thanos et al., 2009). Most recently, our laboratory has shown increased extinction of cocaine lever-pressing in rats when treated with 30 mg/kg DCS but not at 15 mg/kg (Thanos et al., 2011). Since there may be differences between rats and mice in terms of different dose sensitivity and efficiency of DCS on lever pressing for cocaine, we chose to test both 15 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg doses. Thus, the present study seeks to extend research on the potential value of DCS by assessing the effects of treatment with these doses of DCS, (15 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg), in extinction of mouse cocaine self-administration behavior with and without the presence of conditioned cues. Previous studies have not explored how cues interact with DCS during mouse cocaine extinction, nor have they evaluated dose effects.

METHODS

Animals

Four-week-old male c57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) (n = 72) were individually housed and maintained in a controlled room (68–72° F and 40–60% humidity) with a 12-h reverse light-dark cycle (lights off at 0600). All experiments were conducted during the animals’ dark cycle. Purina laboratory mouse chow was available ad libitum throughout the experiment, except during the food training phase, where mice were food restricted for 12 h to encourage lever response for food pellets. Water was available ad libitum throughout the experiment. All experiments were conducted in conformity with the National Academy of Sciences Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NAS, NRC, 1996) and Brookhaven National Laboratory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols (IACUC).

Apparatus

Operant chambers (30 × 25 × 30 cm3 Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA), were placed inside sound attenuation cubicles. Each operant chamber contained two nonretractable levers, one paired with a cue light referred to as the active lever, and the other paired with nothing, the inactive “dummy” lever. The active lever was designated the reinforced lever; while the inactive lever was designated the nonreinforced lever during the food and cocaine self-administration phases. Each box was equipped with infrared locomotor sensors that measured activity during each session. A house light remained on during the entire session. The infusion pump for this experiment was set at a fixed rate of 0.050 ml/s for duration of 2 s. All sessions lasted for 60 min. The experimental protocols were programmed using the Graphic State v3.01 software.

Drugs

Cocaine-HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used in the dose of 1 mg/kg during the self-administration phase. DCS (Sigma-Aldrich) was used in a 15 mg/kg dose (1.5 M; 10 ml/kg i.p.) and a 30 mg/kg dose (3 M; 10 ml/kg i.p.) during extinction. Saline (0.9% NaCl) was used (10 ml/kg i.p.) as the vehicle solution.

Procedures

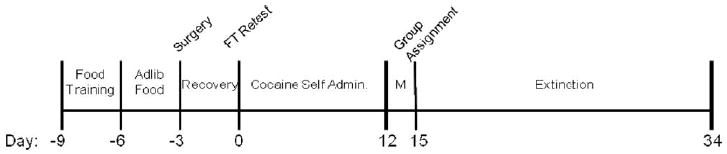

All procedures in this study are illustrated in the timeline Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

DCS extinction experiment timeline. Day numbers are listed and time ranges for each phase are clarified in methods section.

Food training

Mice were trained daily for a minimum of three days using a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule. Pressing the active lever resulted in activation of its associated cue light, as well as the release of a single 20-mg food pellet into the food receptacle. The active cue light was illuminated for 2 s while the food was delivered. After food delivery, the active cue light was turned off for a 30 s “time-out” period during which lever presses and locomotor activity were recorded, but no food pellets could be delivered. The inactive lever had no programmed response. Mice had to meet a criteria of food lever responding as previously described (Larson and Carroll, 2005) of an active/inactive lever press ratio ≥2:1 over three consecutive days. Following this, mice were given food ad libitum for two to three days in their home cage before surgery. Mice underwent surgery to implant a catheter into their jugular vein. After two days of recovery following surgery, the mice were run for one day in the same FR1 food training paradigm to assure they still showed the same active/inactive lever press ratio of ≥2:1 within one session.

Catheterization surgery

The catheterization surgery was similar to and adopted from a previous study (Thanos et al. 2008). Mice were anesthetized with 10/1 mg/kg Ketamine/ Xylazine. A catheter constructed of silastic tubing of ID 0.012” (Plastics One) was implanted into the mouse’s right jugular vein. The catheter was anchored to the vein using 4-0 silk sutures. Successful entry into the jugular vein was confirmed when there was successful drawback of blood into the catheter when slight suction was applied on a syringe connected to the cannula guide. The acrylic portion of the catheter was implanted midscapular on the mouse and closed with a dummy cannula. The mice were allowed to recover for a minimum of two days. Catheter patency was tested 72 h post operatively using a 3.33/1 mg/kg ketamine/xylazine solution. Catheters were deemed patent if the mice lost the “righting reflex” within 3 s of ketamine/xylazine administration. Patency was continually checked every three days during the cocaine self-administration portion of the experiment. Mice were excluded from the study if they did not maintain patency throughout self-administration.

Cocaine self-administration

Mice were run daily for 14 days in the operant boxes with each session 60 min in length and under FR1 parameters, where a reinforced active lever press resulted in i.v. infusion of 1 mg/kg cocaine. At each session’s conclusion, animals were immediately removed from the operant chamber, flushed with a heparin locking solution through their catheter, and returned to their home cages.

Extinction

After the 14th day of self-administration, mice were randomly assigned into six extinction groups (n = 12/group): (1) high dose (30 mg/kg) DCS treatment with cues; (2) high dose (30 mg/kg) DCS treatment without cues; (3) low dose (15 mg/kg) DCS treatment with cues; (4) low dose (15 mg/kg) DCS treatment without cues; (5) vehicle treatment with cues, and (6) vehicle treatment without cues.

During the extinction phase, cues included both auditory (infusion pump) and visual (cue light) cues, and were identical to those present during the cocaine self-administration phase. Extinction without cues was also examined in a similar 60-min protocol but cues were absent. DCS was prepared fresh for each session and administered i.p. immediately after removing the animal from the operant chamber. The extinction phase lasted for 20 sessions (Days 15–34) for mice in all groups.

Statistical analysis

All data points were recorded daily, and each subject’s daily totals were analyzed. Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were performed to analyze active and inactive lever presses and locomotor activity with regard to time (extinction session) and DCS dose. Multiple pair-wise comparisons were performed (Holm-Sidak method) with significance set at unadjusted P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaPlot 11.0. Extinction of the operant response was reported as occurring on days in which animals responded significantly less than they did during cocaine maintenance. The maintenance (M) data were determined as the average of responses from Days 12 to 14 (the final three days of cocaine self-administration).

RESULTS

After the 14 days of self-administration, mice were randomly assigned into the various extinction groups. The mean data is shown for the last three days of self-administration for active and inactive lever presses, as well as locomotor activity. Extinction of the operant response is reported as occurring on days in which animals responded significantly less than they did during cocaine maintenance.

Extinction with cues

Active lever response

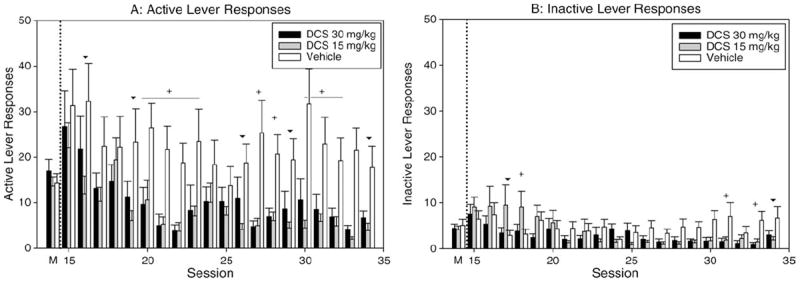

The ANOVA revealed significant main effects of treatment—(DCS) [F(2755) = 7.563; P = 0.002] and time [F(20,755) = 4.972; P < 0.001] on active lever presses (Fig. 2A); but the interaction of treatment by time was not significant [F(40,754) = 1.053; P > 0.05]. Holm-Sidak pairwise comparisons revealed that compared to the vehicle-treated mice, both the low dose DCS (t = 3.629; P < 0.001) and the high dose DCS treated mice showed significantly fewer active lever presses (t = 3.023; P = 0.005). Table I reports results for the pairwise comparisons over time that showed for comparisons with vehicle lower active lever pressing for the low dose DCS on Day 16 and from Day 19 through most of the remaining study days and for high dose on Days 20–23, 27–28, and 30–33.

Fig. 2.

Extinction with cues. A: Active lever responses by treatment during cocaine maintenance and extinction sessions with cues. “M” indicates the average of Days 12–14, the final three days of cocaine maintenance. (+) indicates significant difference between both DCS treated groups and vehicle control by pairwise comparison within time, P < 0.05. (▼) indicates significant differences between low dose DCS and control by pairwise comparison within time, P < 0.05. B: Inactive lever responses by treatment during cocaine maintenance and extinction sessions with cues. (+) indicates significant difference between both DCS-treated groups values and vehicle control by pairwise comparison within time, P < 0.05. (▼) indicates significant differences between low dose DCS and control by pairwise comparison within time, P < 0.05. C: Locomotor beam breaks by treatment during cocaine maintenance and extinction sessions with cues.

TABLE 1.

Table of values indicate results of pairwise comparison of active and inactive lever responses between treatment groups with cues on the extinction day indicated

| Day: | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extinction Session: | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |||

| Cues | Active Lever | Vehicle vs Low DCS | t | 3.289 | 2.802 | 2.585 | 2.667 | 2.436 | 2.667 | 2.369 | 3.303 | 2.369 | 2.423 | 4.413 | 2.761 | 2.328 | 3.161 | 2.247 | ||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| P | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.026 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vehicle vs High DCS | t | 2.734 | 2.707 | 2.423 | 2.276 | 3.343 | 2.233 | 3.425 | 2.328 | 2.017 | 2.815 | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| P | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.027 | <0.001 | 0.021 | 0.045 | 0.005 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Inactive Lever | Vehicle vs Low DCS | t | 2.153 | 1.976 | 2.011 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| P | 0.032 | 0.049 | 0.045 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vehicle vs High DCS | t | 1.976 | 2.294 | 2.188 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| P | 0.049 | 0.022 | 0.029 | |||||||||||||||||||

P and t values reported for sessions where maintenance responses were greater than the indicated day of extinction, with unadjusted P < 0.05. “Day” indicates experiment day.

Inactive lever response

The ANOVA indicated no significant main effects of treatment (DCS) [F(2755) = 1.178; P > 0.05] but significant effects of time [F(20,755) = 3.493; P < 0.001] (Fig. 2B) on inactive lever presses, with an interaction effect [F(40,755) = 1.666; P = 0.007]. Pairwise comparisons revealed that low-dose DCS mice showed significantly lower inactive lever presses compared with vehicle mice on Days 31, 33, and 34 and high-dose DCS mice on Days 30, 31, and 33 (Table I).

Locomotor activity

The ANOVA showed a significant main effect of time on locomotor activity [F(20,755) = 1.645; P = 0.038], but not of treatment [F(2755) = 1.210; P > 0.05] or interaction effects.

Extinction without cues

Active lever response

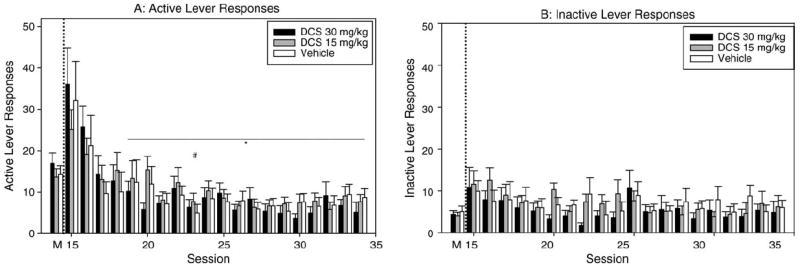

The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time [F(20,755) = 14.817; P < 0.001] (Fig. 3A); but no treatment [F(2755) = 0.0258; P > 0.05] or interaction effects.

Fig. 3.

Extinction without cues. A: Active lever responses by treatment during cocaine maintenance and extinction sessions without cues. (*) indicates significant difference between high dose DCS values for M and given day by pairwise comparison within treatment, P < 0.05. (#) indicates significant difference between vehicle values for M and given day by pairwise comparison within treatment, P < 0.05. Specific P and t values for each day are found in Table I. B: Inactive lever presses by treatment during cocaine maintenance and extinction sessions without cues. C: Locomotor beam breaks by treatment during cocaine maintenance and extinction sessions without cues.

Inactive lever response

The repeated measures ANOVA did not reveal significant main effects of treatment [F(2755) = 0.259; P > 0.05], but showed significant effects of time [F(20,755) = 2.459; P < 0.001], and no interaction effect (Fig. 3B).

Locomotor activity

The ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of treatment [F(2755) = 0.995; P > 0.05], time [F(20,755) 51.189; P > 0.05] or any interaction.

DISCUSSION

While none of the cue-receiving mice met the criteria for extinction, DCS-treated mice did show significantly reduced active lever presses relative to the vehicle mice. The effect of DCS was not significant throughout all the days of extinction (See Fig. 2 and Table I). For instance the effect of low dose DCS was significant for 15/19 extinction days tested while the effect of the high dose DCS was significant for 10/19 days extinction days examined. Thus, further research into the temporal pattern of DCS doses and efficacy in extinction of active lever presses is important.

Our findings were in agreement with recent data showing that DCS (30 mg/kg), administered immediately following CSA extinction sessions (with cues present) significantly decreased lever responses in rats (Nic Dhonnchadha et al., 2010; Thanos et al., 2009). Furthermore, our findings were consistent with previous data which showed DCS to be effective in attenuating operant responses for alcohol during extinction (Vengeliene et al., 2008). The decrease in operant responses during extinction suggests a decrease in cocaine seeking behavior by DCS compared to vehicle mice (with the presence of cues). While these studies were in rats, our present findings in mice provide additional support of the efficacy of DCS in extinction, and this was also consistent with one recent study in mice which treated with DCS (15 and 30 mg/kg) immediately following extinction and showed attenuated lever pressing for food pellets as compared to vehicle treated mice (Shaw et al., 2009). The effect of DCS in extinction with cues also is supported by the Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) literature (Thanos et al., 2011).

At the onset of the extinction phase, all mice showed a spike in inactive lever pressing, presumably due to anxiety and cocaine seeking behavior (Myers and Carlezon, 2010). This may be indicative of more erratic cocaine seeking behavior in the presence of strong drug-paired cues. The increase in inactive lever responses, however, quickly declined for both DCS groups as extinction progressed, but the vehicle group continued to press significantly more than either DCS treatment group. Reduced inactive lever pressing relative to vehicle suggests a decrease in cocaine seeking behavior.

DCS did not have an effect on locomotor activity. Locomotor activity during extinction, regardless of treatment, was only affected by time, which is in agreement with previous studies in rats (Thanos et al., 2011). Mice showed an initial increase in locomotor activity during cocaine extinction, but this effect was eliminated with time, regardless of treatment.

Therefore, our results support that DCS when cues are present, significantly facilitates the rate of extinction. This agrees with previous data showing that DCS must be used in conjunction with the extinction session and cannot take place of formal extinction learning (Torregrossa et al., 2010). Further, DCS-mediated reduction of cocaine seeking behavior was shown to persist even when the drug-reward was reinstated in a novel environment. Rats exposed to cues that are no longer reinforcing will eventually learn and extinguish their behavior, and DCS may expedite this learning process.

Stimulation from cues during extinction may be facilitated by DCS, which may have supported creating new associations between lever pressing and cocaine. Previous studies on the mechanism of DCS suggest that moderate stimulation facilitates the activity of DCS through glucocorticoid and corticosterone release, which in moderate doses helps memory consolidation (Nic Dhonnchadha et al., 2010). Recently, it was found that NMDA receptors on striatal neurons were necessary for acquiring environmental cue associations (Agatsuma et al., 2010), and empirical evidence has shown that the basolateral amygdala is required for expression of conditioned responses to drug paired cues. The nucleus accumbens and dorso-medial prefrontal cortex are also implicated in response to drug cues (Myers and Carlezon, 2010; Torregrossa et al., 2010). For DCS to have its effect, it must then work on the same brain circuitry that is associated with addiction with environmental cues, or on brain regions that modulate these brain regions.

In conclusion, we have shown that the environment in which an animal experiences extinction-training will affect the outcome of DCS treatment. More specifically, with cues present there will be a decrease in cocaine-seeking with DCS that is independent of dose, and without cues there is not a significant medication effect. Clinical research is needed to assess how DCS treatment can help drug abusers by forming new nondrug associations and inhibiting the responses to various drug-related cues that lead to relapse. Our study has shown that DCS will help eliminate drug-paired responses to cue stimuli when received postsession, as opposed to increasing response activation as seen when DCS is administered presession (Price et al., 2009).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joshua Stamos for his help with animal handling in this study.

Contract grant sponsors: NIDA, NIAAA (Intramural Research Program, LNI)

Footnotes

This article is a US government work and, as such, is in the public domain in the United States of America.

References

- Agatsuma S, Dang MT, et al. N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors on striatal neurons are essential for cocaine cue reactivity in mice Biological Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.023. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botreau F, Paolone G, et al. d-Cycloserine facilitates extinction of a cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Behav Brain Res. 2006;172:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Robles A, V-G I, Santini E, Quirk GJ. Consolidation of fear extinction requires NMDA receptor dependent bursting in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2007;53:871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag HS, Shaham Y. Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:169–173. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, et al. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat Protocols. 2006;1:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Conditioned reinforcing properties of stimuli paired with self-administered cocaine, heroin or sucrose: Implications for the persistence of addictive behaviour. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Suppl 1):202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Neuropsychopharmacology of drug seeking: Insights from studies with second-order schedules of drug reinforcement. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526(1-3):186–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood JF, Morley JE, et al. Effect on memory processing by D-cycloserine, an agonist of the NMDA/glycine receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;221(2-3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90709-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin AS, Clemens KJ, et al. Renewal of extinguished cocaine-seeking. Neuroscience. 2008;151(3):659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Meuret AE, et al. Augmentation of exposure therapy with D-cycloserine for social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:298–304. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch R, Petrovic P, De Martino B, Kloppel S, Buchel C, Dolan RJ. The NMDA agonist d-cycloserine facilitates fear memory consolidation in humans. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;19:187–196. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klodzińska A, Chojnacka-Wójcik E. Anticonflict effect of the glycineB receptor partial agonist, D-cycloserine, in rats. Pharmacological analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;152:224–228. doi: 10.1007/s002130000547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Ahmed SH, et al. Neurobiological mechanisms in the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Bloom FE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science. 1988;242:715–723. doi: 10.1126/science.2903550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Kim SW, et al. D-cycloserine augmented exposure therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:835–838. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson EB, Carroll ME. Wheel running as a predictor of cocaine self-administration and reinstatement in female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RJ, Craig LA, Holahan MR, Louis M, Muller RU. NMDA-receptor blockade by CPP impairs post-training consolidation of a rapidly acquired spatial representation in rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1201–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan JB, Handelmann GE, et al. D-cycloserine, a positive modulator of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, enhances performance of learning tasks in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;34:649–653. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Carlezon WA., Jr Extinction of drug- and withdrawal-paired cues in animal models: Relevance to the treatment of addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAS, NRC. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nic Dhonnchadha BA, Szalay JJ, et al. D-cycloserine deters reacquisition of cocaine self-administration by augmenting extinction learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:357–367. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price KL, McRae-Clark AL, et al. D-cycloserine and cocaine cue reactivity: preliminary findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:434–438. doi: 10.3109/00952990903384332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Gonzalez-Lima F. Prefrontal mechanisms in extinction of conditioned fear. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, M D. Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:56–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, et al. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: Use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1136–1144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E, Muller RU, et al. Consolidation of extinction learning involves transfer from NMDA-independent to NMDA-dependent memory. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9009–9017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-09009.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Norwood K, et al. Facilitation of extinction of operant behaviour in mice by d-cycloserine. Psychopharmacology. 2009;202:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Frankland PW, Masushige S, Silva AJ, Kida S. Memory reconsolidation and extinction have distinct temporal and biochemical signatures. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4787–4795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JR, Olausson P, et al. Targeting extinction and reconsolidation mechanisms to combat the impact of drug cues on addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Bermeo C, et al. D-cycloserine facilitates extinction of cocaine self administration in rats. Synapse. 2011 doi: 10.1002/syn. 20922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Bermeo C, et al. D-cycloserine accelerates the extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in C57bL/c mice. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Michaelides M, et al. D2R DNA transfer into the nucleus accumbens attentuates cocaine self administration in rats. Synapse. 2008;62:481–486. doi: 10.1002/syn.20523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa MM, Sanchez H, et al. D-cycloserine reduces the context specificity of pavlovian extinction of cocaine cues through actions in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10526–10533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2523-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengeliene V, Kiefer F, et al. D-cycloserine facilitates extinction of conditioned alcohol-seeking behaviour in rats. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:626–629. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Lu KT, Davis M. Facilitation of conditioned fear extinction by systemic administration or intra-amygdala infusions of d-cycloserine as assessed with fear-potentiated startle in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2343–2351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers NWM, Pulvirenti, Luigi MD, Koob GF, Gillin J, Christian MD. Cocaine abuse and dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;15:63–78. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]