Study took advantage of the hyper-susceptible phenotype of S. aureus ΔdltA against cationic AMPs to investigate the impact of the murine cathelicidin CRAMP to identify its key site of action in neutrophils.

Keywords: CRAMP, NETs, peptide, NADPH oxidase, infection

Abstract

Neutrophils kill invading pathogens by AMPs, including cathelicidins, ROS, and NETs. The human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus exhibits enhanced resistance to neutrophil AMPs, including the murine cathelicidin CRAMP, in part, as a result of alanylation of teichoic acids by the dlt operon. In this study, we took advantage of the hypersusceptible phenotype of S. aureus ΔdltA against cationic AMPs to study the impact of the murine cathelicidin CRAMP on staphylococcal killing and to identify its key site of action in murine neutrophils. We demonstrate that CRAMP remained intracellular during PMN exudation from blood and was secreted upon PMA stimulation. We show first evidence that CRAMP was recruited to phagolysosomes in infected neutrophils and exhibited intracellular activity against S. aureus. Later in infection, neutrophils produced NETs, and immunofluorescence revealed association of CRAMP with S. aureus in NETs, which similarly killed S. aureus wt and ΔdltA, indicating that CRAMP activity was reduced when associated with NETs. Indeed, the presence of DNA reduced the antimicrobial activity of CRAMP, and CRAMP localization in response to S. aureus was independent of the NADPH oxidase, whereas killing was partially dependent on a functional NADPH oxidase. Our study indicates that neutrophils use CRAMP in a timed and locally coordinated manner in defense against S. aureus.

Introduction

The antimicrobial potential of PMN depends on a combination of nonoxidative and oxidative mechanisms involving AMPs, ROS, and NETs. Mammalian AMPs include α-defensins, β-defensins, and cathelicidins that interact with bacteria directly or in concert with other components of the immune system. Human and murine PMN each constitutively express a single cathelicidin: hCAP-18/LL-37 and CRAMP, respectively; both are stored as inactive pro-forms in secondary granules of neutrophils. Proteolytic cleavage of the inactive pro-forms is mediated by proteinase-3 in humans [1] and an unknown protease in mice upon PMN activation and degranulation. Intracellular cleavage and release of the mature peptides into the phagosome seem to be necessary for intracellular killing by PMN but have not yet been described.

Most studies about cathelicidin function have been performed in epithelial cells showing that cathelicidins are strongly induced and secreted after injury or in response to Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in vitro and in vivo [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Lately, the generation of CRAMP-deficient mice made it possible to identify the role of cathelicidins in innate immune defense against invading pathogens [9]. Experimental infection studies in CRAMP-deficient mice have demonstrated a critical role of CRAMP in defense against Streptococcus pyogenes skin infections [10], Escherichia coli urinary tract infections [11], and Neisseria meningitidis bacteremia [3].

Nonoxidative killing by AMPs and oxidative killing by NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS production have long been considered independent of each other. The importance of oxidative killing is evidenced in persons with CGD, who bear inactivating mutations in genes of subunits of the NADPH oxidase and suffer from repeated, life-threatening bacterial and fungal infections [12, 13]. Abnormal pH regulation and ion composition within phagosomes of CGD PMN indicate that the intraphagosomal milieu is tightly regulated by NADPH oxidase and might have a role in microbial killing [14, 15]. The assembled NADPH oxidase transfers electrons into the phagosomal lumen, where they are used to generate superoxide ions, which together with MPO, promote microbial killing [16]. The charge separation by electron transfer is compensated by voltage-gated proton channels and not by the large-conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels described previously [17,18,19,20]. The resulting intraphagosomal pH and ion composition allow the liberation and activation of granule proteases and AMP function [14, 16, 21, 22]. These observations gave evidence that granule proteases and AMPs act in concert with the NADPH oxidase for efficient microbial killing. However, the functional role of NADPH oxidase in AMP processing and activity remains to be clarified.

In addition to active phagocytosis and intracellular killing by AMPs and ROS, NETs provide an extracellular site for microbial killing [23]. In NETs, granule proteases and AMPs are associated with chromatin-DNA and are supposed to kill trapped bacteria by high local concentrations. NETs are released in a specialized form of cell death that depends on the NADPH oxidase [24], providing a new linkage of the NADPH oxidase and AMP function. An extracellular function for CRAMP in NETs can be assumed, as LL-37 has been identified in similar extracellular traps released by mast cells [25].

The major human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus exhibits relative resistance to cationic AMPs as a result of positive-charge modifications to its cell wall, such as peptidoglycan acetylation [26] and teichoic acid D-alanylation [27], the capacity to degrade cationic AMPs with specific proteases [28], and AMP-binding properties of staphylokinase [29]. We had observed previously a reduced virulence of a S. aureus mutant with dealanylated teichoic acids (SA113) ΔdltA in systemic and local infection models [30, 31]. This phenotype was tentatively correlated to an enhanced susceptibility to cathelicidin AMPs [31]. To more fully understand the potential role of CRAMP in the response to S. aureus infection, we investigate the regulation and cellular location of CRAMP expression in murine blood and exudate PMN in this study. We further aimed to specify the role of CRAMP in staphylococcal killing and to identify its key site of action. Particular attention was paid on the contributing roles of NETs and NADPH oxidase to cathelicidin-mediated host defense.

Our results demonstrated an intracellular antimicrobial activity of CRAMP against S. aureus unknown previously. Additional extracellular entrapping and killing of S. aureus by NETs were not mediated by CRAMP, as antimicrobial activity was reduced by binding to DNA; however, NETs may help to protect the host against further bacterial spreading and development of systemic disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains

S. aureus wt (ATCC 35556, SA113 wt) and its isogenic mutants, ΔdltA, Δspa, and Δspa/ΔdltA, were grown overnight in tryptic soy broth (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) at 37°C. For stimulation experiments, a subculture was inoculated 1:100 (v/v) from overnight culture in fresh tryptic soy broth and grown to mid-log phase. Bacteria were washed twice with 0.9% NaCl prior to use.

FITC-labeling of staphylococci

S. aureus subculture was grown to mid-log phase in fresh tryptic soy broth. Bacteria were washed twice with 0.9% NaCl and labeled in 0.1 mg/ml FITC (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS for 1 h at 37°C with shaking. Prior to use, bacteria were washed twice with 0.9% NaCl and resuspended in DPBS with 100 mg/l MgCl2 and 100 mg/l CaCl2 (DPBS++) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Mice and tissue cage model

C57BL/6, CRAMP−/−, and gp91phox−/− mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Animal House of the Department of Biomedicine, University Hospital Basel (Switzerland) and University of California, San Diego (CA, USA), according to the regulations of the Swiss veterinary law and the Veterans Administration of San Diego Committee on Animal Use, respectively. Mice were killed by CO2 or i.p. injection of 500 mg/kg Thiopenthal® (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA).

Female mice (12–14 weeks old) were anesthetized, and sterile Teflon tissue cages were implanted s.c., as described previously [31]. Two weeks after surgery, the sterility of tissue cages was verified. To harvest TCF for isolation of PMN, mice were anesthetized by isofluorane (Minrad Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA), and TCF was percutaneously collected with EDTA.

Antibody generation

Two New Zealand White rabbits were immunized by repetitive s.c. injections of 150 μg synthetic CRAMP peptide (GL Biochem Shangai, China) in adjuvant (MPL®+TDM+CWS adjuvant system, Sigma Chemical Co.) at monthly intervals. The titer of the antiserum was estimated by immunoblotting. The IgG fraction from the polyclonal antiserum was isolated on a protein-G sepharose (Amersham Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) column and affinity-purified further via affinity chromatography over a sepharose column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) conjugated with a synthetic CRAMP peptide used as an immunogen. Bound antibody was eluted with 0.1 M glycin (0.002% sodium azide, pH 2.5) and dialyzed against PBS. A portion of the affinity-purified antibody was biotinylated as described previously [32], dialyzed against PBS, and stored at –20°C. To demonstrate specificity, affinity-purified antibody was used to detect native 18 kDa CRAMP from murine bPMN lysates. Affinity-purified anti-CRAMP antibody was specific for one band of ∼18 kDa, corresponding to the predicted size of pro-CRAMP (see Fig. 2A).

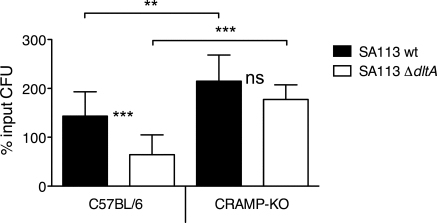

Figure 1.

Bactericidal activity of TCF-PMN from C57BL/6 and CRAMP−/−[knockout (KO)] mice. CFU of viable SA113 wt (solid bars) and SA113 ΔdltA (open bars) after 2 h of incubation with TCF-PMN in vitro are expressed as percentage of the initial inoculum. Data are mean ± sd of three independent experiments. Significant differences are indicated by **, P < 0.01, and ***, P < 0.001. ns, Not significant.

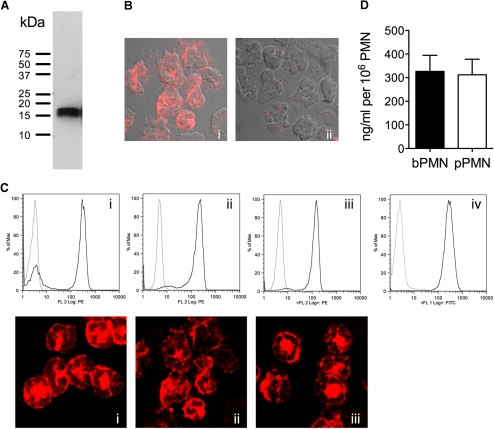

Figure 2.

Intracellular CRAMP expression in blood and exudate PMN. (A) Western blot analysis of bPMN lysates using affinity-purified rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody. (B) Intracellular staining of pPMN with rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (i) and identical staining performed with antibody preincubated with excess of synthetic CRAMP peptide (ii). (C, Upper) PMN purified from blood (i), peritoneal exudate (ii), and TCF (iii) from C57BL/6 mice were stained intracellularly with biotinylated rabbit anti-CRAMP (black lines) or isotype control (gray lines) antibody, followed by RPE-conjugated Streptavidin and analyzed by flow cytometry. (iv) Purified TCF-PMN stained with the neutrophil marker NIMP-R14 (black line) or isotype control (gray line) antibody followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat antibody. Graphs are representative of two to five independent experiments. (C, Lower) bPMN (i), pPMN (ii), and TCF-PMN (iii) were immunolabeled with rabbit anti-CRAMP or isotype control (not shown) antibody, followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody and examined by confocal microscopy. Isotype controls showed no detectable staining. Fluorescence micrographs (original magnification, ×100) are representatives of three independent experiments. FL 2, Fluorescence 2. (D) Total intracellular CRAMP in lysates of bPMN and pPMN of at least three C57BL/6 mice was determined by ELISA.

PMN isolation

For peripheral bPMN, mouse blood was harvested by intracardiac puncture in EDTA. bPMN were isolated as described previously for human PMN [33] but using a modified density gradient centrifugation on a discontinuous Percoll gradient with 59% and 67% Percoll (Amersham Biotech) in PBS. bPMN were collected at the interface of the two Percoll layers.

For pPMN, 1 ml 3% thioglycollate (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) were injected i.p. After 6 h, pPMN were collected by peritoneal lavage with 5 ml RPMI-1640 complete medium (5% FBS, 2 mM glutamate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1.5 mM HEPES, nonessential amino acids) and pelleted by centrifugation.

For TCF-PMN, TCF was collected in EDTA and pelleted by centrifugation.

Where mentioned, bPMN, pPMN, and TCF-PMN were purified over a Percoll gradient as described above to a purity of >97% (NIMP-R14 staining), and viability of PMN was 99% as assessed by trypan blue staining.

Stimulation of PMN for flow cytometry and immunofluorescence

After isolation from blood, peritoneum, or TCF, erythrocytes were lysed in water, and PMN were resuspended in DPBS++ at 1–2 × 106 cells/ml. PMN were incubated with 1 μg/ml PMA, unlabeled (for flow cytometry) or FITC-labeled (for immunofluorescence) SA113 Δspa and SA113 Δspa/ΔdltA for 15 and 30 min at 37°C, 200 rpm. Stimulation was stopped on ice, and PMN were collected by centrifugation for further use in flow cytometry or immunofluorescence. Supernatants were collected, and released CRAMP was measured by ELISA.

Immunofluorescence

After stimulation, cells were spun onto glass coverslips and fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. After permeabilization with 0.2% saponin for 30 min at room temperature and 5 min in methanol, cells were blocked with 2% NGS or normal donkey serum for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were stained with affinity-purified rabbit anti-CRAMP (1 μg/ml), biotinylated rabbit anti-CRAMP (5 μg/ml), goat anti-cathepsin D (10 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and rabbit anti-LAMP-1 (10 μg/ml, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) antibodies, followed by donkey anti-rabbit/goat IgG-Cy3 antibody (7.5 μg/ml, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) or Streptavidin-Alexa647 (10 μg/ml, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Isotype-matched antibody served as negative controls. To confirm specificity of antibody binding, parallel slides were treated identically with affinity-purified rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody that had been preincubated for 1 h at room temperature with 20 μg/ml synthetic CRAMP peptide, which abolished staining (see Fig. 2B). Specimens were analyzed with a Zeiss Axiovert 100 M microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Germany) using the confocal system LSM 510 META with LSM 510 v3.2 SP2 software (Carl Zeiss AG).

Flow cytometry

Cells were blocked with 2% NGS, fixed with 4% PFA, and permeabilized for intracellular staining with 0.1% saponin. Rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) has been used to block FcR binding of IgG. After Fc-blocking, cells were stained sequentially with biotinylated rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody (1 μg/ml) and Streptavidin-RPE (0.25 μg/ml), RPE-conjugated rat anti-CD11b or the neutrophil marker rat anti-mouse NIMP-R14 (10 μg/ml, own hybridoma), and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat antibody (7.5 μg/ml, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Biotinylated rabbit IgG and rat IgG2a (PharMingen) were used as isotype controls.

PMN killing assay

TCF-PMN were resuspended in DPBS++ (with 10% pooled mouse plasma), and 2 × 105 PMN were incubated with SA113 wt or ΔdltA at a MOI of 1 and incubated at 37°C, 200 rpm. After 2 h, samples were diluted in H2O (pH 11) to lyse PMN, and serial dilutions were plated on MHA to enumerate surviving intra- and extracellular bacteria. As bacteria proliferate during time of incubation, CFU of viable bacteria after 2 h are expressed as percentage of the initial inoculum.

Intracellular killing assay

pPMN were resuspended at 1 × 106 PMN in RPMI 1640 (10 mM HEPES, 2% pooled mouse plasma), seeded into 24-well plates, and allowed to adhere for 1 h. PMN were infected with SA113 wt and ΔdltA at a MOI of 1, centrifuged at 800 g for 5 min to synchronize phagocytosis, and incubated further at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 10 min. Lysostaphin (50 U) was added for 10 min to kill extracellular bacteria. Immediately (0 min) and 30 min after lysostaphin treatment, PMN were lysed with H2O (pH 11), and serial dilutions were plated on MHA to assess surviving intracellular bacteria. Intracellular killing was calculated as the percentage of intracellular bacteria at 30 min versus 0 min.

NET-dependent killing assay

pPMN were resuspended at 2 × 106 PMN in RPMI 1640 (10 mM HEPES, 2% pooled mouse plasma), seeded into 24-well plates, and activated with 50 nM PMA for 4 h. The medium was replaced carefully with medium containing cytochalasin D (10 μM), with or without 50 U DNase1 to degrade NETs. Samples were infected with SA113 wt and ΔdltA at a MOI of 0.01, centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min, and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 30 min. Wells were scraped thoroughly, and serial dilutions were plated on MHA to assess surviving bacteria. NET-dependent killing was calculated as percentage of bacteria incubated without neutrophils.

Immunofluorescence of NETs

bPMN or pPMN (2×105) were seeded in poly-L-lysine-covered 16-well glass chamber slides, allowed to settle, and treated with PMA (50 nM), SA113 Δspa, and SA113 Δspa/ΔdltA at a MOI of 10 or left unstimulated for 4 h. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA, blocked with 2% NGS, and stained with affinity-purified rabbit anti-CRAMP (1 μg/ml) and donkey anti-rabbit IgG-Cy3 (7.5 μg/ml) antibody. Controls were done with isotype-matched antibody. For labeling of DNA, SYTOX® Green (1 μM, Molecular Probes) or DAPI (1 μg/mL, Sigma Chemical Co.) was used. Specimens were analyzed as described above in immunofluorescence.

Bacterial killing assay

2×105 CFU of SA113 wt and ΔdltA were incubated in the presence of or absence of 10 μM synthetic CRAMP for 2 h at 37°C. To test the effect of DNA on the antimicrobial activity of CRAMP, 10 μg/ml eukaryotic DNA (from salmon sperm, Sigma Chemical Co.) was added. At indicated time-points, aliquots were taken, and serial dilutions were plated on MHA to assess surviving bacteria.

ELISA

An ELISA for CRAMP was developed using 96-well flat-bottom immunoplates (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA). Plates were coated overnight with 1 μg/ml affinity-purified rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody in 1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 4°C. After blocking with 1% casein in PBS, samples and standards were added and incubated for 2 h. Biotinylated anti-CRAMP antibody (400 ng/ml) was added for 1 h and incubated further with Streptavidin-HRP (Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA). After incubation for 30 min with tetramethylbenzidine substrate (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA), reaction was stopped with 1 M H2SO4, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Between each step, plates were washed four times with PBS (0.05% Tween-20). All incubations were carried out at room temperature.

Immunoblot analysis

pPMN (1×106) were stimulated for 15 min with PMA, SA113 wt, or left unstimulated. Cells were then lysed in 0.9% NaCl containing 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), which were blotted with affinity-purified rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody (1 μg/ml), followed by HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (0.16 μg/ml), and were visualized with ECL (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on films (Kodak).

Statistical analysis

PMN and NET-dependent killing assays were analyzed with one-way ANOVA. Flow cytometry data were analyzed with Wilcoxon signed rank test; intracellular killing assays were analyzed with paired Student’s t-test. Statistical analysis was done with Prism 5.0a (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

PMN-derived CRAMP is active against S. aureus

D-alanylation of teichoic acids by the dlt operon renders S. aureus resistant to cationic AMPs [27]. A staphylococcal ΔdltA mutant described previously was found hypersusceptible to cationic AMPs such as α-defensins and cathelicidins, whereas being normally resistant to oxygen-dependent neutrophil killing [27, 28, 30]. Here, we sought to exploit the differential sensitivity of S. aureus SA113 wt and its isogenic ΔdltA mutant to better understand the regulation, cellular localization, and function of neutrophil-derived CRAMP. We used exudate PMN from tissue cages (TCF-PMN) to investigate CRAMP activity on S. aureus by a PMN population similar to that encountered in vivo. TCF-PMN from C57BL/6 mice exhibited significantly increased bactericidal activity against SA113 ΔdltA compared with wt in vitro (Fig. 1), confirming the ΔdltA phenotype found in the presence of human PMN [30]. In contrast, TCF-PMN from CRAMP−/− mice showed similar bactericidal activity against SA113 wt and ΔdltA. In addition, the bactericidal activity of CRAMP−/− TCF-PMN against SA113 wt was significantly lower than of C57BL/6 PMN (Fig. 1). The susceptibility of SA113 ΔdltA to CRAMP−/− TCF-PMN was abolished, demonstrating that neutrophil-dependent killing of SA113 ΔdltA is mediated predominantly by CRAMP. This finding allows the ΔdltA mutant to serve as a powerful tool to study CRAMP function and activity. Furthermore, the decreased bactericidal activity of CRAMP−/− PMN implies that the expression of CRAMP in PMN is indeed important for the defense against S. aureus in vivo, despite the apparent resistance of the bacterium to the isolated AMP in vitro.

Degranulation of CRAMP does not occur during PMN migration

First, the specificity of affinity-purified rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody was tested by immunoblot analysis of bPMN lysates. The antibody recognized a single band at ∼18 kDa, corresponding to the predicted size of the CRAMP pro-form (Fig. 2A). The anti-CRAMP antibody was also specific for CRAMP in immunofluorescence, as preincubation of the anti-CRAMP antibody with excess synthetic CRAMP abolished staining on pPMN (Fig. 2B). Next, we studied the location and the site of action of CRAMP by investigating intracellular CRAMP expression by flow cytometry in C57BL/6 PMN. To exclude that exudation from the bloodstream itself affects CRAMP expression, PMN purified from TCF and peritoneal exudates were compared with peripheral bPMN. CRAMP was expressed intracellularly in PMN from all sites (Fig. 2C, i–iii, upper row). MFI was similar in all purified PMN, and total CRAMP content from pPMN was comparable with bPMN (Fig. 2D), indicating no detectable loss of CRAMP during exudation from blood. Purified PMN were >97% positive for the granulocyte marker NIMP-R14 antibody, as shown for TCF-PMN in Fig. 2C, iv (upper row). Using fluorescence microscopy, we showed that CRAMP is distributed in a granular pattern in PMN from blood, peritoneal cavity, and TCF (Fig. 2C, i–iii, lower row). These results indicate that CRAMP-containing granules are not released during recruitment of PMN, such that full antimicrobial activity can be exerted at the site of infection.

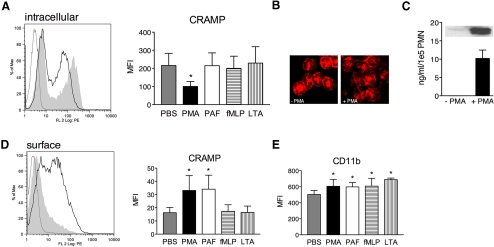

PMN release CRAMP after PKC activation

Degranulation of secondary granules in human PMN was shown to be dependent on PKC [34]. The signaling pathways promoting release of CRAMP after stimulation of murine PMN are unknown. We first investigated the intrinsic ability of C57BL/6 pPMN to secrete CRAMP in response to the PKC activator PMA (10−6–10−8 M) by flow cytometry. Unpurified pPMN were used to avoid preactivation of PMN by Percoll purification. Therefore, two populations with bright and dim fluorescence are seen in the histograms, which were identified as PMN (62.29±9.18%) and monocytes (30.29±9.46%) by Wright’s stain (data not shown). As shown in Figure 2C, ii, PMN correspond with the bright CRAMP-expressing population. The fluorescence histogram of PMA-stimulated versus nontreated cells shows a reduction in intracellular MFI. Intracellular CRAMP was decreased significantly after PMA stimulation at all tested concentrations, as illustrated in the bar graph for 10−6 M PMA (Fig. 3A). To identify the physiological conditions required for CRAMP secretion, we stimulated PMN further with agonists occurring during infection. We tested the host factor PAF (10−5–10−7 M) as well as different known MAMPs, namely fMLP (10−6–10−8 M), S. aureus LTA (10−5–10−7 g/ml; Fig. 3A), synthetic lipopeptide palmitoyl-3-cysteine-serine-lysine-4 (10−5 g/ml), and Salmonella abortus equis LPS (10−6–10−7 g/ml; data not shown). Surprisingly, none of the tested stimuli induced a detectable change of intracellular CRAMP. Using fluorescence microscopy, we confirmed that PMN stimulated with 10−6 M PMA had less intracellular CRAMP, and its distribution was more disperse than in nontreated cells (Fig. 3B). Analysis of supernatants from stimulated PMN by ELISA and immunoblot (Fig. 3C, inset) confirmed that CRAMP was released after PMA stimulation (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Stimulation-induced intracellular decrease and surface translocation of CRAMP. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of unpurified pPMN from C57BL/6 mice stimulated for 15 min with PMA (black line) or left untreated (shaded area) and subsequently stained intracellularly with biotinylated rabbit anti-CRAMP or isotype control (gray line) antibody, followed by RPE-conjugated Streptavidin. Bar graph shows MFI of nontreated or pPMN treated with different stimuli. (B) Immunofluorescence of nontreated and PMA-stimulated bPMN stained with rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody, followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody. Fluorescence micrographs (original magnification, ×100) are representatives of three independent experiments. (C) Released CRAMP from bPMN nonstimulated or stimulated with PMA detected by ELISA and Western blot analysis (inset). (D) Nonpermeabilized cells stained for surface-associated CRAMP as described in A. Bar graph shows MFI of nontreated or pPMN treated with different stimuli. (E) MFI of nontreated or pPMN treated with different stimuli stained with RPE-conjugated rat anti-CD11b antibody. Representative histograms of three independent experiments are shown. Data are mean ± sd of three independent experiments with two to three mice/group. Significant differences are indicated by *, P < 0.05.

It was shown previously that during secondary granule release, lactoferrin and LL-37 transiently locate to the cell surface [35, 36]. Thus, we examined surface translocation of CRAMP as readout for secretion in response to stimulation. Nontreated cells had no detectable CRAMP on their surface, whereas cells stimulated with all concentrations of PMA (10−6 M shown) and 10−5 M PAF showed surface localization of CRAMP with significantly increased MFI compared with nontreated cells (Fig. 3D). All other stimuli did not induce surface translocation of CRAMP at any concentration tested (Fig. 3D).

As a control for degranulation of secretory vesicles and gelatinase granules, we investigated surface localization of CD11b on stimulated PMN. Surface CD11b was increased on PMN after all stimuli compared with nontreated cells at all tested concentrations (Fig. 3E, representative concentrations). Taken together, these results indicate that secretory vesicles and gelatinase granules are more readily exocytosed than secondary granules under the tested conditions.

Our results give evidence that significant amounts of CRAMP can be released from granules into the extracellular space but most probably not under conditions encountered in bacterial infection.

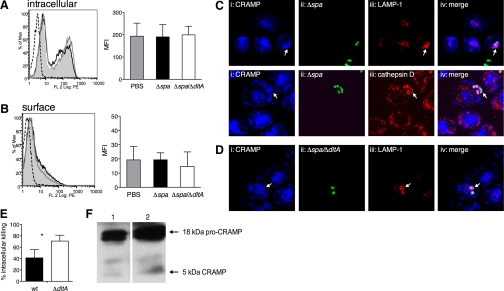

CRAMP is recruited to the phagosome and kills S. aureus intracellularly

The inability of PMN to secrete CRAMP after exposure to bacterial components raised the question of whether viable S. aureus induce the release of CRAMP. In the following experiments, we used the spa deletion mutants SA113 Δspa and Δspa/ΔdltA instead of SA113 wt and ΔdltA to avoid the confounding factor of unspecific IgG binding to Protein A. pPMN were infected with SA113 Δspa and Δspa/ΔdltA for 15 min, and intracellular CRAMP expression and surface localization were studied by flow cytometry. In pPMN, infected with SA113 Δspa and Δspa/ΔdltA, intracellular and surface localization of CRAMP remained unaltered compared with nontreated cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Interestingly, confocal microscopy revealed that CRAMP localized with internalized S. aureus strains after infection (Fig. 4, C and D, arrows). We hypothesized that this localization of CRAMP is the result of granule fusion with S. aureus-containing phagosomes. Indeed, the phagosomal marker LAMP-1 colocalized with CRAMP at the site of S. aureus-containing phagosomes (Fig. 4C, upper, and D, arrows). Granule fusion to the phagosome was also confirmed by colocalization of CRAMP with cathepsin D (Fig. 4C, lower). No differences in localization of CRAMP toward the resistant SA113 Δspa and the CRAMP-susceptible Δspa/ΔdltA mutant were observed. Secretion of CRAMP into the extracellular space after 30 min of infection with both strains was not detectable by ELISA (data not shown). Although PMN are able to secrete CRAMP after soluble stimuli, these data point toward a preferential, intracellular retention of CRAMP in infection to kill S. aureus in phagolysosomes.

Figure 4.

Intracellular localization and activity of CRAMP in S. aureus infection. (A and B) Flow cytometric analysis of pPMN from C57BL/6 mice infected for 15 min with SA113 Δspa (black lines) and SA113 Δspa/ΔdltA (gray lines) or left untreated (shaded areas), stained with biotinylated rabbit anti-CRAMP or isotype control (dotted lines) antibody, followed by RPE-conjugated Streptavidin. (A) Permeabilized cells stained for intracellular CRAMP and (B) nonpermeabilized cells stained for surface-associated CRAMP. Bar graphs show MFI of nontreated (gray bars), SA113 Δspa-infected (solid bars), and SA113 Δspa/ΔdltA-infected (open bars) PMN. Representative histograms of three independent experiments are shown. Data are mean ± sd of three independent experiments with two mice/group. (C and D) Immunofluorescence of bPMN infected for 30 min with FITC-labeled SA113 Δspa and Δspa/ΔdltA (MOI 1). Colocalization of CRAMP, FITC-labeled S. aureus, LAMP-1, and cathepsin D: (i) immunostaining of CRAMP with biotinylated rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody followed by Streptavidin-Alexa647, (ii) FITC-labeled SA113 Δspa and Δspa/ΔdltA, (iii) immunostaining of LAMP-1 with rabbit anti-LAMP-1 or cathepsin D with goat anti-cathepsin D antibody followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit/goat antibody, and (iv) overlay of i–iii. Arrows indicate colocalization of markers with S. aureus. Fluorescence micrographs (original magnification, ×150) are representatives of three independent experiments. (E) Intracellular killing of SA113 wt (solid bar) and ΔdltA (open bar; MOI, 1) by pPMN of C57BL/6 mice 30 min after infection. Data are mean ± sem of three independent experiments. Significant differences are indicated by *, P < 0.05. (F) Immunoblotting of PMN lysates. pPMN (1×106) of C57BL/6 mice were lysed, and cell lysates were run on SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-CRAMP or isotype control antibodies. Lysates of untreated PMN (Lane 1) and PMN infected with SA113 wt (Lane 2).

Consequently, we performed an intracellular killing assay using S. aureus-infected pPMN to evaluate whether CRAMP is not only recruited but also active in phagolysosomes. SA113 wt and ΔdltA were killed intracellularly to 41.2% and 70.77%, respectively (Fig. 4E). SA113 ΔdltA was significantly more susceptible to such intracellular killing. From this finding, we conclude that the active form of CRAMP is present in phagolysosomes.

To show whether CRAMP is processed from the pro-form to the active form in the phagosomes, pPMN were stimulated with SA113 wt and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. In untreated and infected cells, the pro-form of CRAMP appeared as two bands at 18 kDa. The active 5-kDa form of CRAMP was increased after infection with SA113 wt (Fig. 4F), indicating intracellular processing of CRAMP during infection. Unexpectedly, a faint band of active CRAMP was found in uninfected cells.

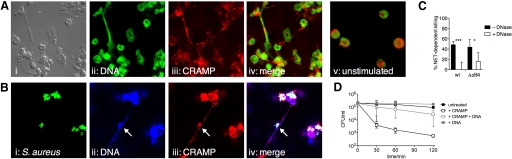

CRAMP is present in NETs, but DNA binding reduces CRAMP activity

Besides their phagocytic activity, human neutrophils were recently found to entrap and kill S. aureus extracellularly by forming NETs when phagocytic killing is exhausted [23]. Proteases and AMPs are associated with NETs, comprising an extracellular site of bactericidal action of granule contents [37]. Therefore, we first investigated NETs induction in murine PMN following stimulation with the potent activator PMA and with viable S. aureus SA113 Δspa as a biologically relevant stimulus. Following both stimuli, NET formation was induced within 4 h in bPMN (Fig. 5, A and B) and pPMN (not shown); unstimulated cells did not release DNA (Fig. 5A, v). Under the conditions tested, PMA induced more NETs than S. aureus, and interestingly, not all PMN formed NETs. In PMA-induced NETs, CRAMP was associated with extracellular DNA (Fig. 5A, iv). In NETs induced by S. aureus, CRAMP colocalized with entrapped bacteria (Fig. 5B, i–iv, arrows), but most of the S. aureus-infected PMN died after phagocytosis (own observation). Nevertheless, these results raised the possibility that association within NETs represents an extracellular site of action for CRAMP. To investigate the antibacterial activity of NETs, PMA-activated pPMN were incubated with SA113 wt and ΔdltA in the presence of cytochalasin D to inhibit phagocytic uptake. SA113 wt and ΔdltA were killed with similar efficiency in the presence of NETs (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, when NETs were degraded with DNase, the killing of SA113 wt was abolished completely, and ΔdltA remained partially susceptible (Fig. 5C). DNase itself did not affect the viability of SA113 wt and ΔdltA (data not shown). From the similar susceptibility of SA113 ΔdltA and wt to NET-dependent killing, we concluded that CRAMP, although present, is not the only important effector in the antimicrobial activity of NETs against S. aureus. Tight association of the cationic AMP with anionic DNA may reduce access of the peptide to the microbial cell surface. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the bactericidal activity of 10 μM synthetic CRAMP on SA113 ΔdltA in the presence and absence of eukaryotic DNA. Indeed, the bactericidal activity of CRAMP against SA113 ΔdltA was abolished in the presence of DNA (Fig. 5D); the presence of DNA alone had no effect on the growth of SA113 ΔdltA. This data demonstrate that NET-associated CRAMP has reduced antimicrobial activity against S. aureus.

Figure 5.

Induction of NETs and antimicrobial activity against S. aureus. (A and B) Immunofluorescence of bPMN activated for 4 h with PMA (A, i–iv) and SA113 Δspa (B, i–iv). (A) Colocalization of DNA and CRAMP: (i) bright field, (ii) SYTOX® Green-labeled DNA, (iii) immunostaining of CRAMP with rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody, followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody, and (iv) merge of i–iii. (v) Immunofluorescence of unstimulated bPMN, indicating no NETs formation after 4 h. (B) Colocalization of DNA, CRAMP, and S. aureus: (i) FITC-labeled SA113 Δspa, (ii) DAPI-labeled DNA, (iii) immunostaining of CRAMP with rabbit anti-CRAMP antibody, followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody, and (iv) merge of i–iii. Arrows indicate colocalization of markers with S. aureus. Fluorescence micrographs (original magnification, ×150) are representatives of three independent experiments. (C) NET-dependent killing of SA113 wt and ΔdltA (MOI, 0.01). NETs were treated with (open bar) or without (solid bars) DNase before infection to distinguish the contribution of DNA and the other NETs components to the killing. (D) Antimicrobial activity of synthetic CRAMP against SA113 ΔdltA in the presence or absence of eukaryotic DNA. Data are mean ± sd of three independent experiments. Significant differences are indicated by *, P < 0.05, and ***, P < 0.001.

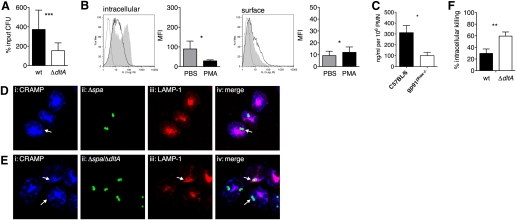

NADPH oxidase is a weak contributor to CRAMP expression and response

Following NADPH oxidase activation, the resulting changes of intraphagosomal pH and ionic milieu were proposed to be essential for liberating granule enzymes into the phagosome [16, 21, 22]. These granule enzymes are likely necessary for cleavage of CRAMP into its active form, raising the question of whether NADPH oxidase-dependent liberation of granule enzymes might affect the processing and activity of CRAMP. We hence investigated function and phagosome translocation of CRAMP in gp91phox−/− mice lacking a functional NADPH oxidase. We assessed the bactericidal activity of gp91phox−/− TCF-PMN toward SA113 wt and ΔdltA in vitro. gp91phox−/− TCF-PMN were highly impaired in the killing of both strains compared with C57BL/6 TCF-PMN (Fig. 6A, compared with Fig. 1). The persistent, increased susceptibility of SA113 ΔdltA in gp91phox−/− TCF-PMN suggests that they still possess active CRAMP.

Figure 6.

Contribution of NADPH oxidase to CRAMP function. (A) Bactericidal activity of TCF-PMN from gp91phox−/− mice. CFU of viable SA113 wt (solid bar) and SA113 ΔdltA (open bar) after 2 h of incubation with TCF-PMN are expressed as percentage of the initial inoculum. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of pPMN from gp91phox−/− mice stimulated for 15 min with PMA (black lines) or left untreated (shaded areas) and stained with biontinylated rabbit anti-CRAMP or isotype control (gray lines) antibody, followed by RPE-conjugated Streptavidin. (Left) Permeabilized cells stained for intracellular CRAMP and (right) nonpermeabilized cells stained for surface-associated CRAMP. Bar graphs show MFI of nontreated (shaded bars) and PMA-stimulated (solid bars) pPMN. Representative histograms of three independent experiments are shown. Data are mean ± sd of three independent experiments. (C) Total intracellular CRAMP in lysates of 106 pPMN from C57BL/6 (solid bar) and gp91phox−/− mice (open bar) was determined by ELISA. (D and E) Immunofluorescence of bPMN of gp91phox−/− mice infected for 30 min with FITC-labeled SA113 Δspa (D) and Δspa/ΔdltA (E; MOI, 1). Colocalization of CRAMP, FITC-labeled S. aureus, and LAMP-1: (i) immunostaining of CRAMP with biotinylated anti-CRAMP antibody, followed by Streptavidin-Alexa647, (ii) FITC-labeled SA113 Δspa and Δspa/ΔdltA, (iii) immunostaining of LAMP-1 with rabbit anti-LAMP-1 antibody, followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody, and (iv) merge of i–iii. Arrows indicate colocalization of markers with S. aureus. Fluorescence micrographs (original magnification, ×150) are representatives of two independent experiments. (F) Intracellular killing of SA113 wt (solid bar) and ΔdltA (open bar; MOI, 1) by pPMN of gp91phox−/− mice 30 min after infection. Data are mean ± sem of three independent experiments. Significant differences are indicated by *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, and ***, P < 0.001.

To exclude a defect in granule release, we stimulated gp91phox−/− pPMN with PMA for 15 min and studied intracellular CRAMP expression and surface localization by flow cytometry. Intracellular CRAMP was decreased significantly after PMA stimulation, as shown in the fluorescence histogram and bar graph in Figure 6B (left panels). PMA-stimulated cells showed more surface localization of CRAMP than nontreated cells with significantly increased MFI (Fig. 6B, right panels). Thus, we found no defect of degranulation in gp91phox−/− pPMN. However, the MFI of intracellular CRAMP (Figs. 6B vs. 4A) and total intracellular CRAMP (Fig. 6C) of nontreated gp91phox−/− pPMN was lower than in pPMN of C57BL/6 mice, indicating a reduced basal intracellular CRAMP level. Further, we infected gp91phox−/− PMN with SA113 Δspa and Δspa/ΔdltA strains and observed that CRAMP was still recruited to internalized bacteria, but LAMP-1 was only partially colocalizing (Fig. 6, D and E, arrows). Intracellular killing assays revealed that gp91phox−/− PMN are impaired significantly in intracellular clearance of SA113 wt (P=0.0109) and ΔdltA (P=0.0392) compared with C57BL/6 PMN. SA113 ΔdltA remained more susceptible than wt (Fig. 6F), suggesting the existence of active CRAMP in these PMN. We could not detect active CRAMP in lysates of infected PMN by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). An explanation for this might be the overall reduced presence of the CRAMP pro-form, which leads to undetectable, low amounts of the active form after infection.

Besides the establishment of an antibacterial milieu in the phagosome, NADPH oxidase activity was also described to be required for the formation of NETs [24]. Indeed, PMN from gp91phox−/− mice were unable to induce NETs (data not shown). Taken together, our data showed that the NADPH oxidase is only a weak contributor to the antimicrobial function of CRAMP.

DISCUSSION

Since the original discovery of CRAMP in murine PMN [9], most studies have been performed on CRAMP expression and function in keratinocytes and other epithelial cells. As a result of a lack of α-defensins, CRAMP is among the major cationic AMPs in murine PMN [38]. In this study, we provide evidence that PMN-derived CRAMP confers antimicrobial activity against the pre-eminent human pathogen S. aureus. Furthermore, we identified two different sites of action of CRAMP: intracellularly in the phagolysosome and extracellularly associated in NETs, accentuated by DNA degradation.

Our data show that PMN-derived CRAMP is active against S. aureus, despite its high resistance against AMPs in vitro. This result is consistent with a previous study showing that bPMN from C57BL/6, but not from CRAMP−/− mice, blocked the proliferation of Group A Streptococcus, another major Gram-positive pathogen with several well-defined, cathelicidin-resistance mechanisms [10, 39]. To study CRAMP function, we made use of the S. aureus mutant ΔdltA, which was shown previously to have a hypersusceptible phenotype to cationic AMPs in vitro and in a local murine infection model [31]. Here, we demonstrated that the susceptibility of SA113 ΔdltA to murine PMN was mediated selectively by CRAMP using CRAMP−/− PMN. This finding is strengthened by a previous study using human PMN, which showed that killing of SA113 ΔdltA is mediated predominantly by α-defensins, the major cationic AMPs in human PMN, and does not depend on oxygen-dependent killing mechanisms [30]. The susceptibility of SA113 ΔdltA to other PMN-derived AMPs (e.g., lactoferrin, lysozyme) was found to be less pronounced than for CRAMP [40, 41], and major contributions to that resistance are provided by other staphylococcal virulence determinants; i.e., resistance to lysozyme is associated with acetylation of peptidoglycan [26], and resistance against lactoferrin [42] and lipocalin [43] is governed by multiple iron uptake systems in S. aureus, which might not be affected in the ΔdltA phenotype. Although we cannot exclude that in addition to increased susceptibility to AMPs, pleiotropic effects of dltA deletion contribute to the observed phenotype. On the other hand, an additional defect in killing mechanisms of CRAMP−/− mice is rather unlikely, as CRAMP−/− mice have normal phagocytic and oxidative burst activity and show similar protease activity as wild-type mice [8, 10].

Most studies about PMN activation and degranulation have been performed using PMN isolated from peripheral blood. As PMN exert their antimicrobial function, mainly after exudation from blood, the question arose as to whether CRAMP is retained during migration. The comparison of PMN migrated to tissue cages and the peritoneal cavity with bPMN showed that CRAMP is not released extensively during exudation. This is in agreement with a study of granule mobilization during in vivo exudation of human PMN [44]. The authors showed that blood and exudate PMN have similar total content of lactoferrin and MPO in secondary and primary granules, respectively [44]. Nevertheless, our result for TCF-PMN contrasts with a previous study showing that TCF-PMN from guinea pigs have reduced MPO and lysozyme content compared with peritoneal exudate PMN [45]. The retention of secondary and also primary granules, which harbor the most potent AMPs, including CRAMP, during extravasation, may be crucial for efficient microbial killing at the site of infection.

As little is known about extra- or intracellular activity of CRAMP, we focused on the identification of its site of action. Although we found degranulation of CRAMP after strong activation of PMN with PMA and PAF, soluble MAMPs and more importantly, live S. aureus did not induce secretion of CRAMP to the extracellular space. Surface expression of CD11b, however, was increased with all stimuli even at the lowest concentrations tested. Our findings indicate that degranulation of secondary granules for extracellular antimicrobial activity does not occur in infection, and up-regulation of surface receptors from gelatinase granules and secretory vesicles might improve the uptake of invading pathogens. The human cathelicidin hCAP-18 was shown to accumulate at the PMN surface following stimulation by fMLP [36]. In contrast, fMLP did not lead to surface translocation of CRAMP in pPMN, which might be explained by different reactivities of human blood and murine pPMN. Nevertheless, surface-translocated CRAMP might contribute to the killing of bacteria during their phagocytosis. The signaling pathways that link ligation of surface receptors or activation of PKC to degranulation of secondary granules include phospholipids, the MAPK p38, Ca2+, and the Src kinase Fgr, Rab GTPases, and SNARE molecules [34]. Their respective roles for CRAMP mobilization are the subject of further investigation.

CRAMP was recruited to S. aureus-containing phagosomes, where it exerted intracellular antimicrobial activity on S. aureus, consistent with the work of Sorenson et al. [1], showing that hCAP-18 is recruited to phagosomes after internalization of latex beads by human PMN. Cathelicidins are inactive without further processing after PMN activation. By the increased intracellular killing of the hypersusceptible SA113 ΔdltA mutant and immunoblots of infected PMN, we demonstrated the intracellular presence and activity of CRAMP. Cleavage of CRAMP is possibly mediated by cathepsins and neutrophil elastase, which are recruited to the phagosome as shown for cathepsin D. Interestingly, intracellular CRAMP was mainly present as a pro-form. Similar results were found for hCAP-18, which was mainly present as the pro-form in phagosomes of human PMN [1]. The presence of active CRAMP in uninfected PMN might be an artifact of thioglycollate-induced attraction of PMN. Staphylococcal infection increased the expression of active CRAMP, but still only low amounts were detectable. This finding was contradictory to our high intracellular killing of SA113 ΔdltA. An explanation for the low detectable amounts might be the interaction of active CRAMP with negatively charged macromolecules (e.g., DNA), as shown for LL-37 [46, 47] or the bacterial membrane. In summary, our data showed that the main function of CRAMP seems to be intracellular.

We demonstrated that murine PMN are able to form NETs after activation by PMA and viable S. aureus in vitro in a manner similar to human PMN. Interestingly, not all PMN in culture made NETs, and this effect was more apparent when PMN were stimulated with S. aureus. This observation suggests that not all PMN form NETs at a given time after infection and that age or other mechanisms may regulate which PMN form NETs after phagocytosis. Although CRAMP colocalized with entrapped S. aureus in NETs, CRAMP activity could not fully explain NET-mediated killing of S. aureus, as SA113 wt and ΔdltA were killed to a similar extent. Extracellular killing of S. aureus therefore requires contributions from additional antimicrobial components of NETs, including histones. This is consistent with the finding that human NETs pretreated with antibodies against histones show reduced killing of S. aureus and Shigella flexneri [23]. In contrast, D-alanylation of teichoic acids enhances resistance against NET-dependent killing in nonencapsulated but not encapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae [48]. Unlike S. aureus and other pathogens, pneumococci are not killed by the antimicrobial components in NETs [49]. The bactericidal activity of CRAMP was impaired when associated with NETs, and release of soluble CRAMP after degradation of the DNA backbone of NETs restored bactericidal activity against SA113 ΔdltA. Our study provides first evidence that NET-associated AMPs may be in a state of reduced activity; this idea is supported by the fact that the antimicrobial activity of LL-37 [47] and CRAMP was inactivated in the presence of DNA. We hypothesize that NETs may serve as a storage site of antimicrobial active peptides and enzymes to combat bacteria that are freed during NET breakdown or following DNase expression by certain pathogens.

The proposed dependence of granular protease liberation on the NADPH oxidase activity [16, 21, 22] let us hypothesize an impaired processing of CRAMP in gp91phox−/− mice. Although we found reduced killing of S. aureus wt and ΔdltA by PMN from gp91phox−/− mice, the function of NADPH oxidase could not be linked to CRAMP activity, as SA113 ΔdltA remained significantly more susceptible to killing by gp91phox−/− PMN than the wt. However, total intracellular CRAMP was reduced in the absence of a functional NADPH oxidase, as determined by ELISA. In CGD patients and gp91phox−/− mice with mutations in the gp91phox or p22phox genes, both membrane subunits of the NADPH oxidase are absent [50, 51]. As CRAMP and the membrane subunits of NADPH oxidase are localized in the same granule [52], a lack of the NADPH oxidase membrane complex might alter membrane integrity and thereby lead to reduced granular content. Another explanation for the reduced intracellular CRAMP level might be augmented degranulation, as described previously for primary granules in CGD neutrophils, resulting in decreased levels of human α-defensins [53].

The results of our study provide first evidence that PMN-derived CRAMP exhibits direct intracellular activity, ensuring rapid initial protection from invading pathogens. NETs harboring CRAMP during prolonged infection may serve for storing AMPs, which might be freed during DNase expression by certain pathogens.

AUTHORSHIP

N. J. J., M. S., K. A. R., and S. A. K. performed experiments. N. J. J., M. S., and S. A. K. analyzed the results and made figures. N. J. J., R. G., V. N., A. P., and R. L. designed the research and wrote the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by The Swiss National Foundation, SNF nos. 3100A0-104259/1 and /2 and SNF No. 3100A0-120617. We thank Dr. Gabriela Kuster Pfister (University Hospital Basel) and Prof. Dr. Wolf-Dietrich Hardt (ETH Zürich) for providing gp91phox–/– mice. We also thank Prof. Dr. Friedrich Götz for providing the isogenic SA113 spa-deletion mutants. We thank Fabrizia Ferracin, Zarko Rajacic, and Beat Erne for technical support.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AMP=antimicrobial peptide, bPMN=blood PMN, CGD=chronic granulomatous disease, CRAMP=cathelin-related AMP, ΔdltA=mutant deficient in D-alanyl-lipoteichoid acid, DAPI=4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, DPBS++=Dulbecco’s PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+, hCAP-18=human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide 18, LAMP-1=lysosome-associated membrane protein-1, LSM=laser-scanning microscope, LTA=lipoteichoic acid, MAMP=microbe-associated molecular pattern, MFI=mean fluorescence intensity, MHA=Mueller-Hinton agar, MOI=multiplicity of infection, MPO=myeloperoxidase, NET=neutrophil extracellular trap, NGS=normal goat serum, PAF=platelet-activating factor, PFA=paraformaldehyde, PKC=protein kinase C, PMN=polymorphonuclear neutrophil(s), pPMN=peritoneal PMN, ROS=reactive oxygen species, RPE=R-Phycoerythrin, spa=staphylococcal protein A, TCF=tissue cage fluid, wt=wild-type

References

- Sorensen O. E., Follin P., Johnsen A. H., Calafat J., Tjabringa G. S., Hiemstra P. S., Borregaard N. Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3. Blood. 2001;97:3951–3959. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorschner R. A., Pestonjamasp V. K., Tamakuwala S., Ohtake T., Rudisill J., Nizet V., Agerberth B., Gudmundsson G. H., Gallo R. L. Cutaneous injury induces the release of cathelicidin anti-microbial peptides active against group A Streptococcus. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:91–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman P., Johansson L., Wan H., Jones A., Gallo R. L., Gudmundsson G. H., Hokfelt T., Jonsson A. B., Agerberth B. Induction of the antimicrobial peptide CRAMP in the blood-brain barrier and meninges after meningococcal infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6982–6991. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01043-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L., Thulin P., Sendi P., Hertzen E., Linder A., Akesson P., Low D. E., Agerberth B., Norrby-Teglund A. Cathelicidin LL-37 in severe Streptococcus pyogenes soft tissue infections in humans. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3399–3404. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01392-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsuzawa H., Ouhara K., Yamada S., Fujiwara T., Sayama K., Hashimoto K., Sugai M. Innate defenses against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection. J Pathol. 2006;208:249–260. doi: 10.1002/path.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Santiago B., Hernandez-Pando R., Carranza C., Juarez E., Contreras J. L., Aguilar-Leon D., Torres M., Sada E. Expression of cathelicidin LL-37 during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in human alveolar macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2008;76:935–941. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01218-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Martinez S., Cancino-Diaz M. E., Cancino-Diaz J. C. Expression of CRAMP via PGN-TLR-2 and of α-defensin-3 via CpG-ODN-TLR-9 in corneal fibroblasts. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:378–382. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger C. M., Gallo R. L., Finlay B. B. Interplay between antibacterial effectors: a macrophage antimicrobial peptide impairs intracellular Salmonella replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2422–2427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304455101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo R. L., Kim K. J., Bernfield M., Kozak C. A., Zanetti M., Merluzzi L., Gennaro R. Identification of CRAMP, a cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide expressed in the embryonic and adult mouse. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13088–13093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizet V., Ohtake T., Lauth X., Trowbridge J., Rudisill J., Dorschner R. A., Pestonjamasp V., Piraino J., Huttner K., Gallo R. L. Innate antimicrobial peptide protects the skin from invasive bacterial infection. Nature. 2001;414:454–457. doi: 10.1038/35106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chromek M., Slamova Z., Bergman P., Kovacs L., Podracka L., Ehren I., Hokfelt T., Gudmundsson G. H., Gallo R. L., Agerberth B., Brauner A. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin protects the urinary tract against invasive bacterial infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:636–641. doi: 10.1681/01.asn.0000926856.92699.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M. The respiratory burst oxidase. Curr Opin Hematol. 1995;2:55–60. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199502010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curnutte J. T. Chronic granulomatous disease: the solving of a clinical riddle at the molecular level. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;67:S2–S15. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiszt M., Kapus A., Ligeti E. Chronic granulomatous disease: more than the lack of superoxide? J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal A. W., Geisow M., Garcia R., Harper A., Miller R. The respiratory burst of phagocytic cells is associated with a rise in vacuolar pH. Nature. 1981;290:406–409. doi: 10.1038/290406a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal A. W. The function of the NADPH oxidase of phagocytes and its relationship to other NOXs in plants, invertebrates, and mammals. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:604–618. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia J., Tinker A., Clapp L. H., Duchen M. R., Abramov A. Y., Pope S., Nobles M., Segal A. W. The large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel is essential for innate immunity. Nature. 2004;427:853–858. doi: 10.1038/nature02356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Essin K., Gollasch M., Rolle S., Weissgerber P., Sausbier M., Bohn E., Autenrieth I. B., Ruth P., Luft F. C., Nauseef W. M., Kettritz R. BK channels in innate immune functions of neutrophils and macrophages. Blood. 2009;113:1326–1331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-166660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essin K., Salanova B., Kettritz R., Sausbier M., Luft F. C., Kraus D., Bohn E., Autenrieth I. B., Peschel A., Ruth P., Gollasch M. Large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel activity is absent in human and mouse neutrophils and is not required for innate immunity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C45–C54. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00450.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Femling J. K., Cherny V. V., Morgan D., Rada B., Davis A. P., Czirjak G., Enyedi P., England S. K., Moreland J. G., Ligeti E., Nauseef W. M., DeCoursey T. E. The antibacterial activity of human neutrophils and eosinophils requires proton channels but not BK channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:659–672. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves E. P., Lu H., Jacobs H. L., Messina C. G., Bolsover S., Gabella G., Potma E. O., Warley A., Roes J., Segal A. W. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ flux. Nature. 2002;416:291–297. doi: 10.1038/416291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal A. W. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V., Reichard U., Goosmann C., Fauler B., Uhlemann Y., Weiss D. S., Weinrauch Y., Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs T. A., Abed U., Goosmann C., Hurwitz R., Schulze I., Wahn V., Weinrauch Y., Brinkmann V., Zychlinsky A. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:231–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kockritz-Blickwede M., Goldmann O., Thulin P., Heinemann K., Norrby-Teglund A., Rohde M., Medina E. Phagocytosis-independent antimicrobial activity of mast cells by means of extracellular trap formation. Blood. 2008;111:3070–3080. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera A., Herbert S., Jakob A., Vollmer W., Götz F. Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant? The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:778–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschel A., Otto M., Jack R. W., Kalbacher H., Jung G., Götz F. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8405–8410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschel A., Collins L. V. Staphylococcal resistance to antimicrobial peptides of mammalian and bacterial origin. Peptides. 2001;22:1651–1659. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T., Bokarewa M., Foster T., Mitchell J., Higgins J., Tarkowski A. Staphylococcus aureus resists human defensins by production of staphylokinase, a novel bacterial evasion mechanism. J Immunol. 2004;172:1169–1176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L. V., Kristian S. A., Weidenmaier C., Faigle M., Van Kessel K. P., Van Strijp J. A., Gotz F., Neumeister B., Peschel A. Staphylococcus aureus strains lacking D-alanine modifications of teichoic acids are highly susceptible to human neutrophil killing and are virulence attenuated in mice. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:214–219. doi: 10.1086/341454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristian S. A., Lauth X., Nizet V., Goetz F., Neumeister B., Peschel A., Landmann R. Alanylation of teichoic acids protects Staphylococcus aureus against Toll-like receptor 2-dependent host defense in a mouse tissue cage infection model. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:414–423. doi: 10.1086/376533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer E. A., Wilchek M. Protein biotinylation. Methods Enzymol. 1990;184:138–160. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)84268-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth R., Jonsson A. K., Vretblad P. A rapid method for purification of human granulocytes using percoll A comparison with dextran sedimentation. J Immunol Methods. 1981;43:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(81)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy P., Eitzen G. Control of granule exocytosis in neutrophils. Front Biosci. 2008;13:5559–5570. doi: 10.2741/3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain S. D., Jutila K. L., Quinn M. T. Cell-surface lactoferrin as a marker for degranulation of specific granules in bovine neutrophils. Am J Vet Res. 2000;61:29–37. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2000.61.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stie J., Jesaitis A. V., Lord C. I., Gripentrog J. M., Taylor R. M., Burritt J. B., Jesaitis A. J. Localization of hCAP-18 on the surface of chemoattractant-stimulated human granulocytes: analysis using two novel hCAP-18-specific monoclonal antibodies. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:161–172. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0906586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartha F., Beiter K., Normark S., Henriques-Normark B. Neutrophil extracellular traps: casting the NET over pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer P. B., Lehrer R. I. Mouse neutrophils lack defensins. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3446–3447. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3446-3447.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo R. L., Nizet V. Innate barriers against skin infection and associated disorders. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2008;5:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmec.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert S., Bera A., Nerz C., Kraus D., Peschel A., Goerke C., Meehl M., Cheung A., Gotz F. Molecular basis of resistance to muramidase and cationic antimicrobial peptide activity of lysozyme in staphylococci. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenmaier C., Kokai-Kun J. F., Kristian S. A., Chanturiya T., Kalbacher H., Gross M., Nicholson G., Neumeister B., Mond J. J., Peschel A. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat Med. 2004;10:243–245. doi: 10.1038/nm991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillen C., McInnes I. B., Vaughan D. M., Kommajosyula S., Van Berkel P. H., Leung B. P., Aguila A., Brock J. H. Enhanced Th1 response to Staphylococcus aureus infection in human lactoferrin-transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:3950–3957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger T., Togawa A., Duncan G. S., Elia A. J., You-Ten A., Wakeham A., Fong H. E., Cheung C. C., Mak T. W. Lipocalin 2-deficient mice exhibit increased sensitivity to Escherichia coli infection but not to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1834–1839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510847103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengelov H., Follin P., Kjeldsen L., Lollike K., Dahlgren C., Borregaard N. Mobilization of granules and secretory vesicles during in vivo exudation of human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1995;154:4157–4165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W., Lew P. D., Waldvogel F. A. Pathogenesis of foreign body infection Evidence for a local granulocyte defect. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:1191–1200. doi: 10.1172/JCI111305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranska-Rybak W., Sonesson A., Nowicki R., Schmidtchen A. Glycosaminoglycans inhibit the antibacterial activity of LL-37 in biological fluids. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:260–265. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner D. J., Bucki R., Janmey P. A. The antimicrobial activity of the cathelicidin LL37 is inhibited by F-actin bundles and restored by gelsolin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:738–745. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0191OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartha F., Beiter K., Albiger B., Fernebro J., Zychlinsky A., Normark S., Henriques-Normark B. Capsule and D-alanylated lipoteichoic acids protect Streptococcus pneumoniae against neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1162–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiter K., Wartha F., Albiger B., Normark S., Zychlinsky A., Henriques-Normark B. An endonuclease allows Streptococcus pneumoniae to escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol. 2006;16:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinauer M. C. The respiratory burst oxidase and the molecular genetics of chronic granulomatous disease. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1993;30:329–369. doi: 10.3109/10408369309082591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock J. D., Williams D. A., Gifford M. A., Li L. L., Du X., Fisherman J., Orkin S. H., Doerschuk C. M., Dinauer M. C. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat Genet. 1995;9:202–209. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faurschou M., Borregaard N. Neutrophil granules and secretory vesicles in inflammation. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak V., Budikhina A., Pashenkov M., Pinegin B. Neutrophil activity in chronic granulomatous disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;601:69–74. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]