Abstract

Objective

To study the effect of electronic medical record (EMR) implementation on preventive services covered by Ontario’s pay-for-performance program.

Design

Prospective double-cohort study.

Participants

Twenty-seven community-based family physicians.

Setting

Toronto, Ont.

Intervention

Eighteen physicians implemented EMRs, while 9 physicians continued to use paper records.

Main outcome measure

Provision of 4 preventive services affected by pay-for-performance incentives (Papanicolaou tests, screening mammograms, fecal occult blood testing, and influenza vaccinations) in the first 2 years of EMR implementation.

Results

After adjustment, combined preventive services for the EMR group increased by 0.7%, a smaller increase than that seen in the non-EMR group (P = .55, 95% confidence interval −2.8 to 3.9).

Conclusion

When compared with paper records, EMR implementation had no significant effect on the provision of the 4 preventive services studied.

Résumé

Objectif

Vérifier l’effet de la mise en œuvre des dossiers médicaux électroniques (DMÉ) sur les services de prévention couverts par le programme ontarien de rémunération au rendement.

Type d’étude

Étude prospective à double cohorte.

Participants

Vingt-sept médecins de famille pratiquant en milieu communautaire.

Contexte

Toronto, Ontario.

Interventions

Dix-huit médecins avaient adopté les DMÉ alors que les 9 autres continuaient d’utiliser les dossiers papier.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Effet du programme incitatif de rémunération au rendement sur la prestation de 4 services préventifs (tests de Papanicolaou, dépistage par mammographies, recherche du sang occulte dans les selles et vaccination contre la grippe) au cours des 2 ans suivant l’introduction des DMÉ.

Résultats

Après ajustement, l’ensemble des services préventifs pour le groupe DMÉ a augmenté de 0,7 %, une augmentation inférieure à celle observée pour le groupe non DMÉ (P = 0,55, intervalle de confiance à 95 % −2,8 à 3,9).

Conclusion

Par rapport aux dossiers papiers, la mise en œuvre des DMÉ n’a pas eu d’effet significatif sur la prestation des 4 services préventifs étudiés.

Electronic medical records (EMRs) have been identified as critical to quality improvement efforts,1–4 and policies favouring the establishment of EMRs are being implemented in the United States and in most Canadian provinces.2,5,6 In 2005, the Ontario government offered a subsidy to selected primary care physicians for the purchase of EMRs.5 Physicians who were eligible were those who had chosen a blended capitation payment system based largely on the age and sex of patients enrolled in their practices. By the end of the program in 2009, most physicians offered the subsidy had purchased EMRs.7 This provided an opportunity to compare groups of physicians in the same communities implementing and not implementing EMRs.

Although EMRs invite hope for improvement,8 there is still much that is unknown about the effect of EMRs on quality and performance. A recent systematic review found that computerized decision-support systems improved practitioner performance, especially with regard to immunizations.9 However, these systems were not commercial, off-the-shelf EMRs like those commonly found in primary care practices. Several studies have found that EMRs might not improve care10–15 and might even be a source of errors.15–17 Studies of EMR implementation have often been descriptive, with very few evaluating measurable outcomes.16 At present, the effect of EMR implementation on the quality of care in small community-based family practices is unknown.

Electronic medical record systems are complex, and their implementation involves changes to many processes; only some changes can be implemented early on. In this study, we focused on preventive services targeted by Ontario’s pay-for-performance program as markers of early progress in EMR implementation. These services were attached to financial incentives and were perceived as representing good care.17 The pay-for-performance target numbers varied by physician and were based on the percentage of enrolled family practice patients being provided with Papanicolaou smears, mammograms, influenza vaccinations, fecal occult blood screening, and primary vaccinations (in children younger than 2 years).18,19

In order to be eligible for funding in Ontario, an EMR system had to include the ability to manage the provision of such preventive services through point-of-care alerts and reminder letters. Although physicians using paper records were also offered financial incentives and were expected to produce an increase in preventive services, those using EMRs had electronic tools that could lead to a greater increase.

Our objective was to compare the differences in provision of these preventive services between community-based family physicians implementing EMRs and those continuing to use paper-based records.

METHODS

Participants

We followed 2 cohorts of physicians: a group of 18 physicians implementing EMRs and a group of 9 physicians using paper records (the non-EMR cohort). Physicians in both cohorts were community-based, were affiliated with a local hospital, and were located in the Toronto area. All were members of the same local after-hours clinic. Physicians were signed out to the clinic and took turns providing walk-in care at a single location on evenings and weekends. No preventive services were offered at the clinic and no clinic data were included in the study.

The physicians in the EMR cohort had previously participated in a pay-for-performance study,20 so data on their characteristics were already available. They switched to the blended capitation model at the end of 2004 and began EMR implementation in the first 4 months of 2006 using the same EMR software. We studied the change in preventive services in the first 2 years of EMR implementation (2006 and 2007). The principal investigator was also a participant in this study (M.G.).

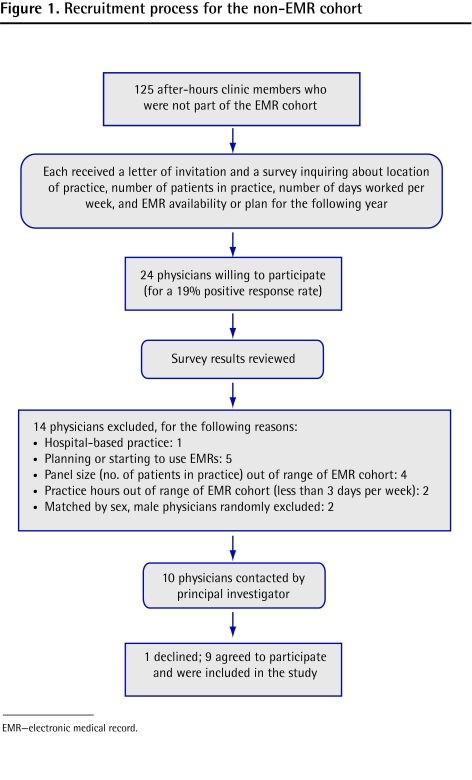

We recruited the non-EMR physicians through a letter of invitation and brief survey sent to all members of the after-hours clinic who were not part of the EMR cohort (125 physicians). These physicians were not eligible for the EMR subsidy. The recruitment process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Recruitment process for the non-EMR cohort

EMR—electronic medical record.

Data sources

The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care provides family physicians with a list of patients in their practices who are eligible for each of the 4 preventive care services. We selected charts from these lists, using a random numbers table, from which we recorded the following: each patient’s age and sex, the presence or absence of a service within the required time period, and any record that a reminder letter had been sent to patients overdue for a service. We entered the data into an Epi Info database.21

We examined information on factors possibly associated with the provision of preventive services.22–32 Data were obtained through a questionnaire administered to all physicians. Following the methods of Glazier et al,33 practice-level data were also derived from linked administrative databases at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). Income quintiles were derived from 2001 census data linked to patient postal codes. Neighbourhood income quintiles and recent immigration status were derived using published methods.33,34 Morbidity and comorbidity (adjusted diagnosis groups and resource utilization bands) were derived using the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups software,35 available from ICES, which has been described elsewhere.36–43 Numbers and percentages of patients with chronic diseases were obtained from linked ICES health databases.38–44

We audited paper charts for physicians in the non-EMR cohort and obtained data from EMR charts for physicians in the EMR cohort. When data were unavailable in the EMR, we retrieved and obtained data from the paper chart.

Five data auditors abstracted data from both paper charts and EMRs. The research coordinator initially audited 10 charts for each service in 2 practices and reviewed this with the principal investigator (M.G.). The coordinator then trained each data auditor, and reviewed at least 10 charts for each service from each auditor. The data were collected on paper forms and entered in the Epi Info database by 2 data entry clerks. Each clerk entered data from a training sample of at least 10 charts for each service. A randomly selected 10% data sample for each service, each year, and each physician was re-audited and entered in the database; we used the κ statistic to compare the 2 audits.

Outcome measures

The study’s end point was whether or not a preventive service was provided and documented within a required time period for each eligible patient. The target patient population consisted of all eligible patients enrolled in the participating practices. Documentation that the patient received the service through another health care provider was acceptable. Information on services is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria, exclusion criteria, and required period for preventive service provision in a pay-for-performance family practice setting

| SERVICE | ELIGIBLE POPULATION | EXCLUSION CRITERIA | REQUIRED PERIOD FOR SERVICE PROVISION* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Papanicolaou smear | Enrolled women aged 35 to 69 y | Previous hysterectomy | Documented service within the past 30 mo before March 31 |

| Screening mammograms | Enrolled women aged 50 to 69 y | History of breast cancer | Documented service within the past 30 mo before March 31 |

| Influenza vaccination | Enrolled patients aged 65 y or older | None | Documented service from October 1st to December 31st of previous y |

| Fecal occult blood test | Enrolled patients aged 50 to 74 y | History of colorectal cancer; history of inflammatory bowel disease; colonoscopy within the past 5 y | Documented service in the past 30 mo before March 31 |

| 5 completed primary immunizations (4 diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccinations and 1 MMR vaccination)† | Enrolled children age 30 to 42 mo as of March 31 | None | Documented completion of vaccinations within the past 12 mo before March 31 |

MMR—measles, mumps, and rubella.

The fiscal year end in Ontario’s health care system is March 31; therefore, March 31, 2007, would be considered the 2006 year end and March 31, 2008, would be the 2007 year end.

Children’s vaccination scores were ultimately excluded from this study as lists of eligible children for 2006 could not be obtained in the non-EMR cohort.

We calculated a composite process score44 by using the total number of charts audited for eligible patients for each service per physician as the denominator and the total number of services documented in the audits as the numerator. We could not obtain lists of eligible children for 2006 in the non-EMR cohort. As a result, children’s vaccinations were excluded from the composite score.

We compared the change in the proportion of patients who received preventive services between the EMR and non-EMR cohorts during EMR implementation. A 5% increase was considered the minimum clinically important difference.

Sample size calculation

We calculated the sample size required to have an 80% power to detect a clinically important increase in service provision of 5% or higher20 in the first 2 years of EMR implementation (assuming relatively stable rates in the non-EMR cohort and with rates of influenza vaccination ranging from 83% to 88%) using an α level of .05, and determined that 40 charts per service per provider would be required. To further increase statistical power, we audited 50 charts per year per service per physician. Physicians who practise in groups might influence one another; this would reduce the variation in practice and might inflate the observed effect.45 Based on our previous pay-for-performance study,20 the estimated intraclass correlation coefficient46 due to clustering of physicians within practices was 0.01. If we assume that, on average, the recruited physicians were clustered within groups of 4 physicians, and that the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.01, the inflation factor would be 1.03 ([1 + (4 - 1) × 0.01]), which should have a negligible effect on the sample size required.

Analysis

We compared unadjusted percentages using χ2 tests and compared adjusted percentages using multivariate logistic regression analysis. We used generalized estimating equations to adjust for the clustering structure of the data in regression models. When comparing the 2 groups, we adjusted for patient age for each individual patient,47 physician sex,20 years since each physician’s medical school graduation,22 and Certification in Family Medicine (ie, CCFP) status26 using multivariate logistic regression analysis. Administrative data could not be used for adjustment, as these data were not available to us at the patient level. Percentage of fecal occult blood tests provided might have been different from the other services provided; the provincial provision rate was low and there was a concurrent public health campaign in 2007.48,49 As a result, we re-analyzed the 2 cohorts with this screen excluded.

As the principal investigator was also a participant in the study, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding her practice data.

We performed analyses with SAS software, version 9.1. All tests were 2-sided using an α level of .05. The study was approved by the University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board; the Sunnybrook Research Institute’s Research Ethics Board approved the use of ICES data. All participating physicians provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the EMR and non-EMR physicians and their practice populations are presented in Table 2 and Table 3,22, 34–43 respectively. Physician characteristics between the 2 cohorts were similar. Patients in the EMR cohort were slightly younger and had lower levels of morbidity and comorbidity.

Table 2.

Characteristics of physicians in the EMR and non-EMR cohorts

| VARIABLE | NON-EMR COHORT (N = 9) | EMR COHORT (N = 18) |

|---|---|---|

| Year of graduation,* median (range) | 1984 (1966 to 1993) | 1977 (1964 to 1992) |

| Men,* n (%) | 6 (66) | 10 (56) |

| CCFP,* n (%) | 7 (77) | 11 (61) |

| No. of medical doctors per practice,* median (range) | 4 (1 to 6) | 3 (1 to 6) |

| No. of hours worked per week,* median (range) | 44 (28 to 80) | 42 (30 to 60) |

| No. of patients per physician,* median (range) | 1200 (850 to 1600) | 1206 (630 to 2200) |

| No. of Canadian graduates† | 8 | 16 |

CCFP—Certification in Family Medicine, EMR—electronic medical record.

Obtained from self-reports.

Obtained from administrative databases.

Table 3.

Comparison of patient characteristics between the EMR and non-EMR cohort practice populations as of August 31, 2007

| PATIENT VARIABLE* | NON-EMR COHORT (N = 9) | EMR COHORT (N = 18) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, N (mean per physician) | 10 591 (1177) | 23 514 (1306) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 47 (31 to 63) | 45 (27 to 60) |

| Men, n (%) | 4 767 (45.0) | 10 106 (43.0) |

| Neighbourhood income quintile,22 n (%) | ||

| • Unknown | 31 (0.3) | 51 (0.2) |

| • 1 (lowest) | 1594 (15.1) | 3084 (13.1) |

| • 2 | 1438 (13.6) | 3643 (15.5) |

| • 3 | 1951 (18.4) | 4345 (18.5) |

| • 4 | 2414 (22.8) | 5 091 (21.7) |

| • 5 (highest) | 3163 (29.9) | 7300 (31.0) |

| Recent immigrant,22 n (%) | 1148 (10.8) | 1398 (5.9) |

| Comprehensiveness of care,22,34 mean (SD)† | 0.50 (0.34) | 0.54 (0.35) |

| Overall morbidity (resource utilization bands),35,36 mean (SD)‡ | 2.81 (1.14) | 2.73 (1.02) |

| • 0 (lowest), n (%) | 657 (6.2) | 1 047 (4.5) |

| • 1, n (%) | 616 (5.8) | 1 480 (6.3) |

| • 2, n (%) | 1 720 (16.2) | 4778 (20.3) |

| • 3, n (%) | 5 344 (50.5) | 12 567 (53.4) |

| • 4, n (%) | 1 614 (15.2) | 2783 (11.8) |

| • 5 (highest), n (%) | 640 (6.0) | 859 (3.7) |

| Overall comorbidity (adjusted diagnosis groups),35,36 mean (SD)§ | 5.43 (3.48) | 4.77 (3.04) |

| • 0 (lowest level of comorbidity), n (%) | 657 (6.2) | 1046 (4.4) |

| • 1–4, n (%) | 3962 (37.4) | 11 189 (47.6) |

| • 5–9, n (%) | 4615 (43.6) | 9502 (40.4) |

| • ≥ 10 (highest level of comorbidity), n (%) | 1357 (12.8) | 1777 (7.6) |

| Common comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| • Diabetes37 | 1041 (9.8) | 1934 (8.2) |

| • CHF40 | 300 (2.8) | 386 (1.6) |

| • Hypertension38 | 2823 (26.7) | 5594 (23.8) |

| • MI39 | 193 (1.8) | 311 (1.3) |

| • Asthma41 | 1500 (14.2) | 3143 (13.4) |

| • COPD42 | 626 (5.9) | 1120 (4.8) |

| • Mental health issues43 | 2391 (22.6) | 4937 (21.0) |

CHF—congestive heart failure, COPD—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, EMR—electronic medical record, IQR—interquartile range, MI—myocardial infarction, SD—standard deviation.

Obtained from administrative databases.

Comprehensiveness of care was determined by measuring the percentage of bills for 21 common services that were provided by the patients’ own family physicians.

Resource utilization bands indicate morbidity and expected health care system use, from 0 (lowest) to 5 (highest).

Adjusted diagnosis groups indicate comorbidity, from 0 groups (lowest level of comorbidity) to 10 or more groups (highest level).

Results for individual services are presented in Table 4. Nine hundred charts were audited for each service for each year in the EMR cohort and 450 charts were audited in the non-EMR cohort. The number of Pap smears and mammograms increased more in the EMR cohort, while the rate of influenza vaccinations and fecal occult blood testing increased more in the non-EMR cohort. Composite process scores are shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Service provision for individual services in the EMR and non-EMR cohorts before and after EMR implementation

| SERVICE | COHORT | 2006, % | 2007, % | DIFFERENCE, % | DIFFERENCE IN CHANGE BETWEEN EMR AND NON-EMR GROUPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza vaccine | EMR | 70.7 | 69.8 | −0.9 | −8.3% in EMR cohort |

| Non-EMR | 59.2 | 66.5 | 7.4 | ||

| Papanicolaou smear | EMR | 76.1 | 79.7 | 3.6 | +1.1% in EMR cohort |

| Non-EMR | 75.6 | 78.1 | 2.5 | ||

| Fecal occult blood test | EMR | 28.7 | 32.1 | 3.4 | −1.4% in EMR cohort |

| Non-EMR | 41.1 | 45.9 | 4.8 | ||

| Mammogram | EMR | 75.2 | 80.9 | 5.7 | +6.3% in EMR cohort |

| Non-EMR | 78.3 | 77.7 | −0.6 |

EMR—electronic medical record.

Table 5.

Changes in composite process scores for the provision of preventive services between EMR and non-EMR cohorts

| PROVISION OF PREVENTIVE SERVICES* | EMR COHORT | NON-EMR COHORT | DIFFERENCE | ADJUSTED DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE GROUPS† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Including fecal occult blood testing | ||||

| • Composite process score in 2006, % | 63.0 | 63.6 | 0.6 | NA |

| • Composite process score in 2007, % | 65.7 | 67.1 | 1.4 | NA |

| • Difference (95% CI) | 2.7 (0.6 to 5.0) | 3.5 (0.5 to 6.6) | 0.8 (−3.0 to 4.6) | 0.7 (−2.8 to 3.9)‡ |

| Excluding fecal occult blood testing | ||||

| • Composite process score in 2006, % | 74.0 | 71.0 | 3.0 | NA |

| • Composite process score in 2007, % | 76.8 | 74.1 | 2.7 | NA |

| • Difference (95% CI) | 2.8 (0.5 to 5.1) | 3.1 (−0.2 to −6.4) | 0.3 (−3.7 to 4.4) | 0.3 (−3.0 to 3.6)§ |

CCFP—Certification in Family Medicine, CI—confidence interval, EMR—electronic medical record, NA—not applicable.

Preventive services also include Papanicolaou smear tests, influenza vaccination, and screening mammograms.

Adjusted for physician sex, CCFP status, number of years since graduation from medical school, and patient age.

P = .55.

P = .53.

Female physician sex and younger patient age were positively correlated with the likelihood of receiving a service. There was no correlation with years since medical school graduation or Certification status. There was no significant difference in the change in service provision between the 2 groups; differences and confidence intervals were less than 5%. The results were not affected by the exclusion of fecal occult blood screening data.

Physicians in the EMR cohort mailed letters to 23 patients overdue for services in 2005, 265 patients in 2006, and 677 patients in 2007. Physicians in the non-EMR cohort mailed 1 letter in 2006 and none in 2007.

The results were unaffected by the exclusion of the principal investigator’s data. The κ statistic for the 10% of charts that were re-audited was 0.954, consistent with an acceptable level of agreement.

DISCUSSION

We found no statistically significant or clinically important difference in the change in preventive service provision between physicians implementing EMRs and those continuing to use paper records. Other studies have found no difference in the change in care of diabetes between EMR- and paper-based practices11 and no improvement when additional experience with EMR accrues over time.11,13,15

The EMR system we studied included elements that have been associated with an increase in the provision of preventive services, such as point-of-care alerts9,50,51 and the ability to generate reminder letters to patients.52 However, studies have shown that alerts or patient reminders for overdue services, even if available, might not be consistently implemented in practice.11,15,53,54 We found evidence of reminder letter mailings in the EMR cohort, but this did not appear to have had an effect on service uptake.

To frame and explain our results, a qualitative study presented in an accompanying article55 explores the context of this EMR implementation. Similar studies could help to determine what aspects of EMR implementation are associated with improved quality of care.

Limitations

This study was limited to a group of selected physicians in Toronto. However, all physicians in this study were practising in community-based settings, similar to most family physician settings in Ontario.56 Physicians in our cohorts were similar to their colleagues in capitated and reformed fee–for-service models in Ontario urban centres.33

Nineteen percent of physicians using paper records responded to the study invitation; we do not know if their characteristics differed from those of the nonresponders. The participating physicians provided preventive services to a large proportion of their patients. Increases might have been limited by ceiling effects. Also, we studied a single EMR system; results might differ for physicians using other EMR systems.

This was an observational cohort study, and is therefore subject to both measured and unmeasured confounders. In this study, we measured confounders that have been reported in the literature to affect preventive services22–32,47,57,58 and used statistical adjustments to adjust for these factors. There were differences between our 2 cohorts in terms of physician funding mechanisms. However, a recent study using administrative data did not find any consistent difference in the provision of preventive services between Ontario physicians in capitated or reformed fee-for-service groups.59

Conclusion

Among the family physician practices studied, the first 2 years of EMR implementation were not associated with an increase in the provision of preventive services targeted by Ontario’s pay-for-performance program when compared with the continued use of paper records. It should not be assumed that EMR implementation improves care.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a research grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Health System Strategy Division (grant no. 020709) and was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care or the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

One of the drivers of electronic medical record (EMR) implementation is the hope that EMRs can improve quality of care for patients.

The authors examined preventive services with pay-for-performance incentives that should have improved with EMR use owing to electronic tools that assist in timely service provision (eg, alerts, automated reminders).

There was no difference in service provision between physicians using EMRs and those continuing to use paper records (in the first 2 years of EMR implementation).

It should not be assumed that EMR implementation improves care.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Une des raisons qui incitent à adopter les dossiers médicaux électroniques (DMÉ) est l’espoir qu’ils peuvent améliorer la qualité des soins.

Les auteurs ont examiné les services préventifs qui, avec une rémunération au rendement comme mesure incitative, auraient dû s’améliorer avec les DMÉ grâce aux outils électroniques qui facilitent la prestation de ces services en temps opportun (p. ex. signaux d’alerte, rappels automatisés).

Il n’y avait pas de différence de prestation des services entre les médecins utilisant les DMÉ et ceux qui continuaient d’utiliser les dossiers papiers (durant les 2 ans suivant l’introduction des DMÉ).

On ne devrait pas présumer que la mise en œuvre des DMÉ améliore les soins.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study. Drs Greiver and Barnsley contributed to the data gathering. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results and the preparation of the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Canada Health Infoway . Annual report 2007–2008. The evolution of health care: making a difference. Toronto, ON: Canada Health Infoway; 2008. Available from: www2.infoway-inforoute.ca/Documents/Infoway_Annual_Report_2007-2008_Eng.pdf. Accessed 2011 Sep 9. [Google Scholar]

- 2. American recovery and reinvestment act of 2009, Pub L No. 111-5, 123 Stat 115-531. Available from: www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ5/pdf/PLAW-111publ5.pdf. Accessed 2011 Sep 9.

- 3.The health of Canadians—the federal role. Final report. Volume 6: recommendations for reform. Ottawa, ON: Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2002. Available from: www.parl.gc.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/372/soci/rep/repoct02vol6-e.htm. Accessed 2011 Sep 9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romanow RJ. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Commission of the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. Available from: http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/CP32-85-2002E.pdf. Accessed 2011 Sep 9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care . Family Health Network agreement. Toronto, ON: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2005. IT appendix. Physician IT program. [Google Scholar]

- 6.CanadianEMR [website] Provincial programs. Vancouver, BC: CanadianEMR; 2010. Available from www.canadianemr.ca/index.aspx?PID=50. Accessed 2011 Sep 9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toronto, ON: OntarioMD Inc; 2011. EMR Advisor [website] Available from: www.emradvisor.ca. Accessed 2011 Sep 12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilo CM. Transforming care: medical practice design and information technology. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(5):1296–301. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1223–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eccles M, McColl E, Steen N, Rousseau N, Grimshaw J, Parkin D, et al. Effect of computerised evidence based guidelines on management of asthma and angina in adults in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):941. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor PJ, Crain AL, Rush WA, Sperl-Hillen JM, Gutenkauf JJ, Duncan JE. Impact of an electronic medical record on diabetes quality of care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(4):300–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linder JA, Ma J, Bates DW, Middleton B, Stafford RS. Electronic health record use and the quality of ambulatory care in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(13):1400–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou L, Soran CS, Jenter CA, Volk LA, Orav EJ, Bates DW, et al. The relationship between electronic health record use and quality of care over time. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(4):457–64. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3128. Epub 2009 Apr 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon JR, Wahls T, Carlos RC, Pipinos II, Rosenthal GE, Cram P. Failure to recognize newly identified aortic dilations in a health care system with an advanced electronic medical record. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):21–7. W5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crosson JC, Ohman-Strickland PA, Hahn KA, DiCicco-Bloom B, Shaw E, Orzano AJ, et al. Electronic medical records and diabetes quality of care: results from a sample of family medicine practices. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(3):209–15. doi: 10.1370/afm.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell E, Sullivan F. A descriptive feast but an evaluative famine: systematic review of published articles on primary care computing during 1980–97. BMJ. 2001;322(7281):279–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm. A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Available from: www.nap.edu/html/quality_chasm/reportbrief.pdf. Accessed 2011 Sep 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Family Health Network, Ministry of Health and Long Term Care . General blended payment template. Family Health Network agreement. Toronto, ON: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Family Health Network, Ministry of Health and Long Term Care . General blended payment template. Family Health Network agreement. Toronto, ON: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasperski J, Greiver M, Barnsley J, Rachlis V. Measuring quality improvements in preventive care services in the first two family health networks in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto, ON: Ontario College of Family Physicians; 2006. Grant no. G03-05567. Available from: www.ocfp.on.ca/docs/research-projects/2011/04/18/preventive-care-services-in-fhns-project.pdf. Accessed 2011 Sep 14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. Epi Info [computer program]. Version 3.32. Available from: wwwn.cdc.gov/epiinfo. Accessed 2011 Sep 12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):260–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franks P, Clancy CM. Physician gender bias in clinical decisionmaking: screening for cancer in primary care. Med Care. 1993;31(3):213–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lurie N, Slater J, McGovern P, Ekstrum J, Quam L, Margolis K. Preventive care for women. Does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;329(7):478–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308123290707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thind A, Feightner J, Stewart M, Thorpe C, Burt A. Who delivers preventive care as recommended? Analysis of physician and practice characteristics. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1574–5.e1-5. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/54/11/1574.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2011 Sep 15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norton PG, Dunn EV, Soberman L. What factors affect quality of care? Using the Peer Assessment Program in Ontario family practices. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:1739–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zyzanski SJ, Stange KC, Langa D, Flocke SA. Trade-offs in high-volume primary care practice. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkerton PH, Wagner EH, Smith DG, Straley HL. Effect of part-time practice on patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):717–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McIsaac WJ, Fuller-Thomson E, Talbot Y. Does having regular care by a family physician improve preventive care? Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:70–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkelstein MM. Preventive screening. What factors influence testing? Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:1494–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lofters A, Glazier RH, Agha MM, Creatore MI, Moineddin R. Inadequacy of cervical cancer screening among urban recent immigrants: a population-based study of physician and laboratory claims in Toronto, Canada. Prev Med. 2007;44(6):536–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.02.019. Epub 2007 Mar 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walter LC, Lindquist K, Nugent S, Schult T, Lee SJ, Casadei MA, et al. Impact of age and comorbidity on colorectal cancer screening among older veterans. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(7):465–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-7-200904070-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glazier RH, Klein-Geltink J, Kopp A, Sibley LM. Capitation and enhanced fee-for-service models for primary care reform: a population-based evaluation. CMAJ. 2009;180(11):E72–81. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shortell SM. Continuity of medical care: conceptualization and measurement. Med Care. 1976;14(5):377–91. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Johns Hopkins University ACG Case-Mix Adjustment System [computer program] Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Johns Hopkins University ACG System . About the ACG system. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health; 2009. Available from: www.acg.jhsph.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=46&Itemid=61. Accessed 2011 Sep 15. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):512–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, Cauch-Dudek KJ, McAlister FA. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med. 2007;1(1):e18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackevicius CA, Li P, Tu JV. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(8):1028–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ko DT, Alter DA, Austin PC, You JJ, Lee DS, Qiu F, et al. Life expectancy after an index hospitalization for patients with heart failure: a population-based study. Am Heart J. 2008;155(2):324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying patients with physician-diagnosed asthma in health administrative databases. Can Respir J. 2009;16(6):183–8. doi: 10.1155/2009/963098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying individuals with physician diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6(5):388–94. doi: 10.1080/15412550903140865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E, Evans M. Using administrative data to measure ambulatory mental health service provision in primary care. Med Care. 2004;42(10):960–5. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200410000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, Rothberg MB, Benjamin EM, Ma A, et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):486–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064964. Epub 2007 Jan 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ukoumunne OC, Gulliford MC, Chinn S, Sterne JA, Burney PG, Donner A. Methods in health service research. Evaluation of health interventions at area and organisation level. BMJ. 1999;319(7206):376–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7206.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asch SM, Kerr EA, Keesey J, Adams JL, Setodji CM, Malik S, et al. Who is at greatest risk for receiving poor-quality health care? N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1147–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa044464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilkins K, Shields M. Colorectal cancer testing in Canada—2008. Health Rep. 2009;20(3):21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ColonCancerCheck [website] Toronto, ON: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care of Ontario; 2007. Available from: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/coloncancercheck. Accessed 2011 Sep 12. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Balas EA, Weingarten S, Garb CT, Blumenthal D, Boren SA, Brown GD. Improving preventive care by prompting physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(3):301–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Craig TJ, Perlin JB, Fleming BB. Self-reported performance improvement strategies of highly successful Veterans Health Administration facilities. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22(6):438–44. doi: 10.1177/1062860607304928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szilagyi PG, Bordley C, Vann JC, Chelminski A, Kraus RM, Margolis PA, et al. Effect of patient reminder/recall interventions on immunization rates: a review. JAMA. 2000;284(14):1820–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.14.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griffin S, Kinmonth AL. Diabetes care: the effectiveness of systems for routine surveillance for people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000541. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welch WP, Bazarko D, Ritten K, Burgess Y, Harmon R, Sandy LG. Electronic health records in four community physician practices: impact on quality and cost of care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(3):320–8. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2125. Epub 2007 Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greiver M, Barnsley J, Glazier RH, Moineddin R, Harvey BJ. Implementation of electronic medical records. Theory-informed qualitative study. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:e390–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schultz SE, Guttmann A, Jaakkimainen L. Chapter 11. Characteristics of primary care practice. In: Jaakkimainen LUR, Klein-Geltink JE, Leong A, Maaten S, Schultz SE, Wang L, editors. Primary care in Ontario: ICES atlas. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. Available from: www.ices.on.ca/file/PC_atlas_chapter11.pdf. Accessed 2011 Sep 12. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snider J, Beauvais J, Levy I, Villeneuve P, Pennock J. Trends in mammography and Pap smear utilization in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 1996;17(3–4):108–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glazier RH, Creatore MI, Gozdyra P, Matheson FI, Steele LS, Boyle E, et al. Geographic methods for understanding and responding to disparities in mammography use in Toronto, Canada. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(9):952–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jaakkimainen L, Barnsley J, Klein-Geltink J, Kopp A, Glazier R, Sibley L. Performance measures amongst primary care groups in Ontario. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2009. Available from: www.f2fe.com/CAHSPR/2009/docs/A6/a6c%20Liisa%20Jaakkimainen.pdf. Accessed 2011 Sep 12. [Google Scholar]