Abstract

Little longitudinal research has examined progression to more severe bipolar disorders in individuals with “soft” bipolar spectrum conditions. We examine rates and predictors of progression to bipolar I and II diagnoses in a non-patient sample of college-age participants (n = 201) with high General Behavior Inventory scores and childhood or adolescent onset of “soft” bipolar spectrum disorders followed longitudinally for 4.5 years from the Longitudinal Investigation of Bipolar Spectrum (LIBS) project. Of 57 individuals with initial cyclothymia or bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BiNOS) diagnoses, 42.1% progressed to a bipolar II diagnosis and 10.5% progressed to a bipolar I diagnosis. Of 144 individuals with initial bipolar II diagnoses, 17.4% progressed to a bipolar I diagnosis. Consistent with hypotheses derived from the clinical literature and the Behavioral Approach System (BAS) model of bipolar disorder, and controlling for relevant variables (length of follow-up, initial depressive and hypomanic symptoms, treatment-seeking, and family history), high BAS sensitivity (especially BAS Fun Seeking) predicted a greater likelihood of progression to bipolar II disorder, whereas early age of onset and high impulsivity predicted a greater likelihood of progression to bipolar I (high BAS sensitivity and Fun-Seeking also predicted progression to bipolar I when family history was not controlled). The interaction of high BAS and high Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) sensitivities also predicted greater likelihood of progression to bipolar I. We discuss implications of the findings for the bipolar spectrum concept, the BAS model of bipolar disorder, and early intervention efforts.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, Behavioral Approach System sensitivity, impulsivity

Introduction

Since Kraeplin’s (1921) seminal descriptions of manic-depressive illness, or bipolar disorder, researchers have hypothesized that “soft” bipolar conditions (i.e., bipolar disorder not otherwise specified [BiNOS], cyclothymia, bipolar II disorder) sometimes progress to full-blown bipolar I disorder. Surprisingly, few studies have addressed this hypothesis with longitudinal prospective study designs. Retrospective studies suggest that individuals with bipolar I disorder first experience less severe symptoms on average 12 years prior to being diagnosed (Berk et al., 2007). In contrast, the few existing longitudinal studies suggest that only a minority of individuals with bipolar II disorder develop manic or mixed episodes and convert to bipolar I disorder during prospective follow-up—approximately 5–7.5% of adults (e.g., Coryell et al., 1995) and 20–25% of child/adolescent patients (Birmaher et al., 2006; 2009) with initial bipolar II disorder. It is crucially important to identify predictors of worsening prognosis for the unfortunate minority who progress to bipolar I disorder. The present longitudinal study of a large non-patient sample (i.e., not recruited through clinics) of individuals with BiNOS, cyclothymia and bipolar II disorder attempts to characterize this minority. Specifically, the present study examines whether early age of onset, and/or greater behavioral approach system (BAS) sensitivity and impulsivity increase risk for conversion from BiNOS or cyclothymia and bipolar II to bipolar I disorder and from BiNOS or cyclothymia to bipolar II disorder.

Early Age of Onset as a Risk Factor for Conversion to Bipolar I and II Disorders

Childhood/adolescent bipolar disorder onset is predictive of poor prognosis (Berk et al., 2007; Birmaher et al., 2006; 2009; Lewinsohn et al., 1995; Perlis et al., 2004; Strober et al., 2005). There is also some evidence for greater risk of progression to more severe bipolar conditions for individuals with childhood or adolescent onset of ‘soft’ bipolar disorder. In the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Illness in Youth (COBY) study of bipolar I, bipolar II, and BiNOS patients aged 7 to 17, 25% with bipolar II converted to bipolar I disorder and 38% with BiNOS converted to bipolar I or II disorder during the 4 year follow-up (Birmaher et al., 2009). In another longitudinal study, 80 youth (mean age 12.7) hospitalized for major depression with no history of hypomania/mania were followed for 2–4 years (Kochman, et al., 2005). Kochman et al. found increased rate of conversion to bipolar II disorder for children/adolescents with cyclothymic temperament (63.8%), assessed with a self-report measure, vs. those without this temperament (15.2%) during the follow-up. Interestingly, Beesdo and colleagues (2009) found that onset of major depression prior to age 17 was also associated with greater risk for subsequent development of mania or hypomania.

The rates of conversion from ‘soft’ bipolar conditions to more severe bipolar disorders in adolescents and children seem considerably higher than in adult samples. For example, in 5-year and 10-year follow-ups of adult patients with bipolar II disorder, only 5% and 7.5% converted to bipolar I disorder, respectively (Coryell et al., 1995; Joyce et al., 2004). In the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS), a survey of over 4,000 adults annually assessed for three years, 7.1% of individuals with subthreshold hypomania symptoms and 1% of individuals with subthreshold depressive symptoms subsequently developed bipolar disorder (Regeer et al., 2006).

However, patient samples of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders are likely to be more severe and, thus, the rates of conversion to bipolar I and II disorders may be magnified. To address this potential problem, longitudinal studies of non-patient samples of youth with bipolar spectrum disorders are needed. To date, there is only one such study in the literature. In the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP), a randomly selected community sample of adolescents were followed and, by their early 20’s, 2.1% met diagnostic criteria for bipolar I or II disorder and another 5% had subsyndromal bipolar spectrum disorder (Lewinsohn, Klein, & Seely, 2000). After additional follow-up until age 30, only 2.1% of individuals with subsyndromal bipolar spectrum disorder developed bipolar disorder, whereas 39.3% of these individuals developed major depressive episodes (Lewinsohn, Seely, & Klein, 2003). Thus, unlike longitudinal studies of adolescent and child patients with bipolar II and BiNOS disorders, this longitudinal study of a community sample of adolescents did not find an elevated risk of conversion from subthreshold bipolar disorder to bipolar I disorder compared to adult studies.

There are several possible explanations for these divergent findings. One potential explanation is that the patient studies exaggerated the rates of conversion due to bias towards severe symptomatology in their treated samples. Another potential explanation is that the subsyndromal bipolar spectrum disorder, defined by Lewinsohn and colleagues as presence of a period of manic mood and one other symptom, had too low a threshold even for ‘soft’ bipolar conditions (i.e., it does not fit the DSM-IV criteria for bipolar II disorder or cyclothymia). Another potential explanation for divergent findings may be that Lewinsohn and colleagues had longer assessment intervals (only 4 assessments over the 14-year course of the project) compared to more frequent assessments of patient samples in the above studies, thus potentially missing symptoms of mania and hypomania. Additional longitudinal studies of non-patient samples with ‘soft’ bipolar conditions are needed to address these divergent findings and test whether early age of onset increases risk for conversion to bipolar I (and bipolar II) disorder.

Cyclothymia and BiNOS as Risk Factors for Conversion to Bipolar I and II Disorders

Cyclothymic temperament has been linked to greater severity and worse prognosis in individuals with mood disorders of all ages. During 2–4 years of medication-free follow up of adults with cyclothymia, Akiskal, Djenderedjian, Rosenthal, and Khani (1977) found that 28.26% developed hypomania and major depressive episodes, i.e., switched to bipolar II disorder, and an additional 6.52% developed mania, i.e., converted to bipolar I disorder. A more recent prospective study found that 63.8% of children and adolescents with a history of major depressive episodes coupled with cyclothymic temperament developed bipolar II disorder during 2–4 years of follow-up (Kochman et al., 2005). Similarly, Birmaher and colleagues (2006; 2009) found that 38% of their child/adolescent patients (ages 7 – 18 at outset) converted to a bipolar I or II diagnosis during 4 years of follow-up (Birmaher et al., 2009).

Still, there are important gaps in the existing literature on cyclothymia and BiNOS as risk factors for poorer prognosis in bipolar disorders. Studies with an interview assessment of DSM-IV cyclothymia or BiNOS diagnosis and prospective rates of conversion to bipolar II and bipolar I disorders are lacking. Moreover, all three of the prospective studies of individuals with cyclothymia or BiNOS were based on patient samples; thus, examination of the naturalistic course in non-patient samples is needed. The present study addresses these gaps in the literature.

Behavioral Approach System (BAS) Sensitivity and Impulsivity as Risk Factors for Conversion to Bipolar I and II Disorders

To date, research on predictors of progression to a worse diagnosis along the bipolar spectrum has been largely atheoretical, focusing on demographic and clinical predictors of progression. According to the BAS dysregulation model, bipolar spectrum disorders stem from hypersensitivity of a behavioral-motivational system, the Behavioral Approach System (BAS), which facilitates approach to rewards and safety cues in active-avoidance paradigms (Depue et al., 1987; Depue & Iacono, 1989; for review of theory and evidence, see Alloy & Abramson, 2010; Alloy, Abramson, Urosevic, Bender, & Wagner, 2009a; and Urosevic, Abramson, Harmon-Jones, & Alloy, 2008). Individuals with bipolar disorders are hypothesized to be hypersensitive to reward-relevant cues (i.e., both opportunities to gain rewards and negative cues of failure to obtain/loss of rewards). This hypersensitivity leads to extreme shifts in BAS activation, with hypomania/mania reflecting extreme approach behaviors (i.e., BAS hyperactivation) and depression reflecting extreme shutdown of approach behaviors (i.e., BAS hypoactivation). It is important to emphasize that the hypothesized vulnerability to bipolar disorders in this model is a propensity toward excessive BAS activation and deactivation (i.e., BAS hypersensitivity), not the actual activation or deactivation itself, which is considered the more proximal precursor of mood symptoms/episodes.

Consistent with the BAS model, individuals with bipolar I (Meyer, Johnson, & Winters, 2001; Salavert et al., 2007), bipolar II and cyclothymia (Alloy et al., 2008), or prone to bipolar symptoms (Meyer, Johnson, & Carver, 1999) exhibited BAS hypersensitivity, as measured by self-report and greater reward responsiveness on a behavioral task (Hayden et al., 2008). Also consistent with the BAS model, individuals with bipolar spectrum disorders exhibit specific BAS-relevant cognitive styles (Alloy et al., 2009b; Lam, Wright, & Smith, 2004; Scott, Stanton, Garland, & Ferrier, 2000) and greater left frontal cortical activation as assessed by EEG, a neurobiological index of BAS activation (Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1997; Sutton & Davidson, 1997), in response to rewards compared to healthy controls (Harmon-Jones et al., 2008). Finally, in individuals with bipolar I or bipolar spectrum disorders, exposure to BAS activation life events involving goal striving or goal attainment triggers hypomanic and manic episodes (Johnson et al., 2000; 2008; Nusslock, Abramson, Harmon-Jones, Alloy, & Hogan, 2007).

Alloy and colleagues (2006) employed a behavioral high-risk design and found that high BAS sensitivity individuals were more likely to receive a lifetime bipolar spectrum diagnosis (50%) and exhibited greater hypomanic personality and current hypomanic symptoms than moderate BAS sensitivity individuals (8.3%). Moreover, Meyer and colleagues (2001) found that high BAS sensitivity at the time of recovery predicted prospective increases in manic symptoms over six months in a bipolar I sample. Furthermore, Salavert and colleagues (2006) reported that bipolar individuals who experienced a hypomanic/manic relapse over 18 months had higher BAS sensitivity at baseline compared to controls, whereas those who experienced a depressive relapse had a nonsignificant trend towards lower BAS sensitivity compared to controls. These findings support the BAS model of bipolar spectrum disorders.

Although there is growing support for the BAS model of bipolar disorders, one of the key hypotheses of this model has not been tested. Namely, among individuals with ‘soft’ bipolar conditions, are those with greater BAS sensitivity more likely to develop more severe conditions, i.e., bipolar II and bipolar I disorder, over time (Urosevic et al., 2008)? If corroborated, this would not only provide further support for the BAS model of bipolar disorders, but also for the construct of a bipolar spectrum—a set of disorders with the same underlying vulnerability and psychopathology that differs in degree of severity across the spectrum. Thus, the present study can address the debate about whether bipolar spectrum disorders constitute a clinically relevant dimension (for criticism of this spectrum concept, see Baldessarini, 2000).

Levels of Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) sensitivity may also interact with BAS sensitivity to predict progression to bipolar I disorder. Gray (1991) hypothesized that manic individuals would be characterized by high BAS and low BIS sensitivities. According to Gray’s model, then, the combination of high BAS and low BIS should predict conversion to bipolar I disorder (i.e., mania); thus, we also tested this hypothesis in the present study.

Impulsivity, defined as a tendency toward rash, unplanned behavior without reflection, is also elevated in bipolar disorders and stable across mood episodes (Swann et al., 2004). High impulsivity has been associated with disinhibited psychopathology in general (e.g., externalizing disorders) and with poorer adjustment, lower academic achievement, greater suicidality, and greater substance abuse among individuals with bipolar spectrum disorders in particular (Alloy et al., 2009c; Kwapil et al., 2000; Nusslock, Alloy, Abramson, Harmon-Jones, & Hogan, 2008; Swann et al., 2005; 2007). Consequently, trait impulsivity might also predict progression along the bipolar spectrum to a more severe diagnosis, particularly to bipolar I disorder. Indeed, given that mania (bipolar I) is largely differentiated from hypomania (BiNOS, cyclothymia, and bipolar II) by the presence of impairment rather than by differences in the types of symptoms, and impulsivity is predictive of greater impairment and more risky behaviors (Akiskal, Hantouche, & Allilaire, 2003; Alloy et al., 2009c; Dawe, Gullo, & Loxton, 2004; Nusslock et al., 2008), high impulsivity may be especially relevant to prediction of conversion to bipolar I disorder among individuals with “soft” bipolar conditions.

Overview of the Present Study

In summary, only a minority of individuals with ‘soft’ bipolar conditions progress to more severe bipolar disorders, but prior work does not adequately characterize this minority. Preliminary research indicates some candidates for progression to more severe bipolar disorders: early age of onset, presence of cyclothymia or BiNOS, and possibly, BAS hypersensitivity and impulsivity. However, no longitudinal studies have examined all these risk factors to test whether they predict conversion to bipolar I or II disorder in a non-patient sample of individuals with adolescent/childhood onset of bipolar disorders. The present longitudinal study addresses this gap.

This study also expands on the only existing longitudinal community study of adolescents (Lewinsohn et al., 1995, 2000, 2003). Compared with Lewinsohn and colleagues (1995, 2000), we identified a much larger sample (201 vs. 18 in the OADP) of 18 – 24 year old individuals with bipolar II, cyclothymia or BiNOS diagnoses providing adequate power for determining rates of conversion to bipolar I disorder. In addition, this study is the first to prospectively follow individuals into their late 20’s with semi-structured diagnostic interviews at 4-month intervals. The follow-up into young adulthood is important given findings of three peaks of bipolar disorder onset, with two of these peaks occurring prior to the late 20’s (e.g., Bellivier et al., 2001, 2003). Significantly shorter assessment intervals in this study (i.e., 4-month vs. the OADP’s 1-year and 8-year follow-ups) allow us to capture hypomanic and manic symptoms with greater sensitivity throughout this crucial vulnerability period. Importantly, unlike the OADP, the prospective symptom assessments were conducted using the same semi-structured interviews for all assessments, thus ensuring that progression to more severe bipolar diagnoses is not due to differences in assessment methods.

Thus, the present study investigates rates of conversion from cyclothymia or BiNOS to bipolar II and from cyclothymia/BiNOS and bipolar II to bipolar I disorder over 4.5 years of follow-up in a non-patient sample of 18–24 year olds. In addition, we assess whether earlier age of onset, greater BAS sensitivity, and impulsivity predict increased rates of conversion to more severe bipolar conditions. Finally, we examined whether the interaction of BAS and BIS sensitivities predicted conversion to bipolar I disorder.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited for the Longitudinal Investigation of Bipolar Spectrum Disorders (LIBS) Project using a two-stage screening procedure. In Stage I, approximately 20,500 Temple University (TU) and University of Wisconsin (UW) students, ages 18 – 24, completed the revised General Behavior Inventory (GBI; Depue, Krauss, Spoont, & Arbisi, 1989), to identify individuals prone to ‘soft’ bipolar conditions. A subset of participants who met the GBI cutoff criteria: 1) for bipolar spectrum conditions (Hypomania-Biphasic [HB] score > 13 and Depression [D] score > 11), or 2) for the absence of affective psychopathology (HB < 13 and D < 11), as specified by Depue et al. (1989), were identified. Participants from these two groups were chosen to be similar on demographics (sex, age, and race) and invited to the next stage. In Stage II, 1,730 participants were administered an expanded Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia--Lifetime diagnostic interview (exp-SADS-L; Endicott & Spitzer, 1978). The exp-SADS-L interview was modified to allow for derivation of both DSM-IV-TR (2000) and Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC; Spitzer, Endicott, & Robins, 1978) diagnoses.

Exclusion criteria based on the exp-SADS-L were: 1) current or past DSM-IV and/or RDC Manic Episode diagnoses (i.e., bipolar I disorder); 2) current or past DSM-IV and/or RDC diagnoses of primary psychiatric disorder other than bipolar spectrum disorder (e.g., anxiety); and 3) bipolar disorder secondary to current physical illness (e.g., endocrinopathies). However, for the bipolar spectrum group, individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorder secondary to bipolar spectrum disorder (e.g., comorbid alcohol abuse) and, for the control group, individuals with only Specific Phobia diagnoses were included.1 Finally, based on this two-stage screening procedure, two groups of individuals were identified and invited to participate in the longitudinal project: 1) individuals who met both the GBI cutoff criteria for bipolar spectrum conditions and the DSM-IV and/or RDC criteria for cyclothymia, BiNOS, or bipolar II disorder (i.e., the bipolar spectrum group); and 2) individuals who met both the GBI cutoff criteria for absence of affective psychopathology and the DSM-IV and/or RDC criteria for no lifetime diagnosis of psychopathology (i.e., control group). The longitudinal sample consisted of 414 participants (165 men, 249 women)—206 in the bipolar spectrum group (57 cyclothymia or BiNOS, 149 bipolar II disorder) and 208 in the control group. The bipolar spectrum and control groups did not differ on age, sex, or ethnicity (see Alloy et al., 2008). The longitudinal sample was representative of the Stage I screening sample on demographics and did not differ from Stage II eligible individuals who did not participate on demographics, diagnosis, treatment history, and GBI scores (see Alloy et al., 2008).

Given that the aims of the current study were to examine predictors of conversion to more severe diagnoses in the bipolar spectrum, only participants in the bipolar spectrum group were included in the present analyses. The ethnic composition of the bipolar spectrum group was 68.9% Caucasian, 13.1% African-American, 5.1% Hispanic, 3.6% Asian, 0.5% Native American, and 8.2% Other. Five bipolar spectrum participants (who did not differ from the remaining bipolar participants on demographics, clinical variables, or GBI scores) were excluded from the present analyses because they had too much missing data. This left 201 bipolar spectrum participants (43 Cyclothymia, 14 BiNOS, 144 bipolar II) in the present analyses.

Procedure

Participants in the longitudinal study completed a Time 1 assessment and then were assessed every 4 months using questionnaires and semi-structured diagnostic interviews for an average of 4.54 years (SD = 2.74 years). At Time 1, participants completed measures of BAS and BIS sensitivities and impulsivity, as well as initial assessments of their mood symptoms. Diagnostic interviewers were blind to participants’ Stage I and II screening information, including the bipolar spectrum vs. control group status based on the DSM-IV and RDC diagnoses. Conversion to bipolar II disorder was defined as first onset of a major depressive episode (MDE) in participants with past history of a hypomanic episode or first onset of both an MDE and hypomanic episode in participants with no prior history of hypomania. Conversion to bipolar I disorder was defined as the first onset of a DSM-IV-TR manic or mixed episode with or without a history of MDE’s.

Measures

Revised General Behavior Inventory (GBI)

The revised GBI (Depue et al., 1981; 1989) assesses chronic affective disorders in the general population. It contains 73 items measuring the frequency, intensity, and duration of core bipolar experiences on two subscales: Depression (D) and Hypomania and Biphasic (HB) items combined. As recommended by Depue et al. (1989), we used the case-scoring method to identify potential bipolar spectrum and control participants at the Stage I screening. Only items rated a “3” (“often”) or “4” (“very often or almost constantly”) on the GBI 4-point frequency scale counted toward the score on each subscale. Based on Depue et al.’s (1989) recommended cutoffs, participants who scored ≥ 11 on the D scale and ≥ 13 on the HB scale were identified as potential bipolar spectrum participants, whereas those who scored below these cutoffs formed a potential healthy control group. These criteria were based on Depue et al.’s findings (1989) and a pilot study for the LIBS Project in which these cutoffs were validated against diagnoses derived from exp-SADS-L interviews. The GBI has good internal consistency (αs = .90–.96), retest reliability (rs = .71–.74), adequate sensitivity (.78), and high specificity (.99) for bipolar spectrum conditions (Depue et al., 1981; 1989). It has been validated extensively in college, psychiatric outpatient, and offspring of bipolar I patient samples (Depue et al., 1981; 1989). In the LIBS Project Stage II sample, the GBI had α’s = .95 and .87 for the D and HB scales, respectively, and high sensitivity (.93), but low specificity (.41).

Expanded SADS-L diagnostic interview

The exp-SADS-L (Endicott & Spitzer, 1978) is a semistructured diagnostic interview that assesses current and lifetime history of Axis I disorders. It was administered at Stage 2 screening by interviewers blind to participants’ Stage I GBI scores. The original SADS-L was expanded in several ways for the LIBS Project: 1) probes were added to allow for DSM-IV-TR as well as RDC diagnoses; 2) questions were added to better capture the frequency and duration of symptoms for depression, hypomania, mania, and cyclothymia sections; 3) probes were expanded to assess whether participants’ behavioral changes were observable by others; 4) questions’ order was changed to increase the interview’s efficiency and comprehension; and 5) sections were added to assess eating disorders, ADHD, and acute stress disorder, additional probes were added in the anxiety disorders section, and organic rule-out and medical history sections were appended. To gain further specificity than provided by DSM-IV-TR, diagnosis of cyclothymia was operationalized as fulfilling all DSM-IV-TR criteria plus: 1) at least two ≥ 2-day episodes of hypomanic mood with at least two hypomanic symptoms per year; 2) at least two ≥ 2-day episodes of depressed mood with at least two depressive symptoms per year; 3) presence of hypomanic and depressed mood for at least 50% of the day during the respective mood episodes; and 4) presence of this pattern for at least two years if > age 18 or at least one year if < age 18. A diagnosis of BiNOS was given when individuals exhibited: 1) diagnosable hypomanic episodes without diagnosable depressive episodes; 2) a cyclothymic pattern but with hypomanic and depressive periods that did not meet minimum 2-day duration criteria for hypomanic and depressive episodes in cyclothymia (i.e., they exhibited 1-day hypomanic and depressive periods); and 3) hypomanic and depressive periods that were not frequent enough to qualify for cyclothymia (i.e., one hypomanic and depressive period per year).

The exp-SADS-L (and exp-SADS-C described below) interviews were conducted by postdoctoral fellows, Ph.D. students, MAs in clinical psychology, and post-BA salaried research assistants unaware of participants’ Stage I GBI scores. Training consisted of approximately 200 hours of reading and didactic instruction, watching videotaped interviews, role playing, discussing case vignettes, and extensive practice conducting live interviews with supervision and feedback. DSM-IV-TR and RDC diagnoses were determined by a 3-tiered standardized diagnostic review procedure involving project interviewers, senior diagnosticians, and an expert consultant psychiatrist. Final diagnoses were based on consensus of individuals from all 3 tiers. An inter-rater reliability study based on 105 jointly rated exp-SADS-L interviews yielded κs ≥ .96 for bipolar spectrum diagnoses. Inter-rater reliability with the expert psychiatric diagnostic consultant based on 100 exp-SADS-L interviews was κ = .86.

Information regarding age of onset of bipolar spectrum diagnoses was obtained from the exp-SADS-L and was operationalized as the earliest age at which the participant met criteria for either an MDE or hypomanic episode (for those with bipolar II diagnoses) or the earliest age at which the participant exhibited at least one depressive and at least one hypomanic period within a 1-year period (for those with cyclothymia or BiNOS diagnoses). Information regarding family history of bipolar disorders was also obtained from the exp-SADS-L using the family history method and the Family History – Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC; Andreason, Endicott, Spitzer, & Winokur, 1977). Insofar as the FH-RDC have been found to be reliable, family history was not a major focus of the LIBS Project, and the family study method would have been too costly, the family history approach was considered adequate. Given that family history of bipolar disorder is a known risk factor for the occurrence of bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives (McGuffin et al., 2003; Merikangas et al., 2002), we controlled for family history of bipolar disorders in some of our analyses when examining age at onset, BAS sensitivity, and impulsivity as predictors of conversion to bipolar I and II diagnoses (see Data Analysis Approach section).

Expanded SADS-Change (exp-SADS-C; Spitzer & Endicott, 1978)

Prospective onsets of mood episodes were assessed with the exp-SADS-C diagnostic interview administered face-to-face approximately every 4 months during the follow-up; 87.3% of the 4-month assessments occurred on schedule. Interviews that could not be completed face-to-face were completed by phone (approximately 15% were completed by phone). The exp-SADS-C is a semistructured diagnostic interview that assesses prospective changes in severity, duration, and number of clinical symptoms and allows for diagnosis of onsets, remissions, relapses, and recurrences of disorders covered by the interview. It was expanded in the same ways as the exp-SADS-L. In addition, features of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE II; Shapiro & Keller, 1979) were added to the exp-SADS-C to systematically track the course of symptoms and episodes during follow-up. However, the exp-SADS-C inquired about the presence of each symptom of depression and hypomania/mania more frequently (daily) than does the LIFE II (weekly) during the 4-month interval. Exp-SADS-C interviewers were blind to participants’ diagnostic information at the Stage II screening, family history, age at onset, and BAS and impulsivity scores. Like the exp-SADS-L interviews, exp-SADS-C diagnoses were based on consensus of interviewers and senior diagnosticians. In addition, all ambiguous exp-SADS-C interviews and a random 10% of other interviews were reviewed by the expert psychiatric diagnostic consultant. Joint ratings of 60 exp-SADS-C interviews for the LIBS Project yielded good inter-rater reliability (for Bipolar I, κ = 1.0, for Bipolar II, κ = .92, for Cyclothymia/BiNOS, κ = .88). Inter-rater reliability for individual symptom ratings were r’s = .93 for both hypomanic and depressive symptoms. Moreover, a validity study indicated that interviewers dated symptoms on the exp-SADS-C with at least 70% accuracy compared to participants’ daily symptom ratings made over a 4-month interval (Alloy et al., 2008). The exp-SADS-C also provided information about participants’ treatment seeking (medication or psychotherapy) during each 4-month interval since the previous assessment.

Manic and mixed episodes met relevant DSM-IV-TR criteria, including number and duration of symptoms. All manic and mixed episodes were characterized by either hospitalization, presence of psychotic symptoms, and/or grave impairment (e.g., serious legal consequences stemming from risky behavior during manic episode). Details of the criteria used to diagnose bipolar mood episodes on the exp-SADS-C interviews are provided in the appendix.

Self-report symptom measures

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) was used to assess initial levels of depressive symptoms. The BDI has been validated in student samples and the internal and retest reliabilities are good in both clinical and non-patient samples (Beck, Steer & Garbin, 1988). Initial levels of hypomanic/manic symptoms were assessed with the Halberstadt Mania Inventory (HMI; Alloy et al., 1999; Halberstadt & Abramson, 1998), modeled after the BDI, and assessing the affective, cognitive, motivational, and somatic symptoms of hypomania/mania. Like the BDI, the HMI asks participants to choose one of 4 statements graded in severity that best describes their experience. The HMI has good internal consistency (α = .82), convergent validity with the MMPI-Mania scale (r = .32, p < .001), and discriminant validity with the MMPI-Depression scale (r = −.26, p < .001) and BDI (r = −.12, p < .001) (Alloy et al., 1999). The HMI also correlated (r = .46) with hypomanic symptoms rated from exp-SADS-C interviews in the LIBS Project (Alloy et al., 2008) and had an internal consistency of α = .78. Finally, the HMI also shows expected changes as cyclothymic individuals cycle through hypomanic, euthymic, and depressed mood states (Alloy et al., 1999).

BAS and BIS Sensitivities

The BIS/BAS Scales (Carver & White, 1994) were used to assess individual differences in sensitivity of the BAS and BIS. They consist of the BIS scale and BAS scale composed of three subscales—Drive (D), Fun Seeking (FS), and Reward Responsiveness (RR). The four D subscale items (e.g., “When I want something, I usually go all-out to get it”) assess vigor and persistence in reward pursuit, and have an α of .76 and retest reliability of .66 (Carver & White, 1994). The four FS subscale items (e.g., “I will often do things for no other reason than that they might be fun”) assess willingness to approach rewards and novel stimuli on impulse, with an α = .66 and retest reliability = .69 (Carver & White, 1994). Finally, the five RR subscale items (e.g., “When I get something I want, I feel excited and energized.”) assess positive responses to reward stimuli, with an α of .73 and retest reliability of .59. Scores on the BAS subscales can be examined separately or combined as a BAS-Total score. The seven BIS scale items (e.g., “If I think something unpleasant is going to happen, I usually get pretty “worked up”) assess sensitivity to and concern about the possibility of punishment, and have an α of .74 and retest reliability of .66 (Carver & White, 1994). Numerous empirical findings support the construct validity of the BIS/BAS scales (e.g., Carver & White, 1994; Diego, Field, & Hernandez-Reif, 2001; Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1997; Sutton & Davidson, 1997). In this study, α’s = .74 for BIS, .72 for BAS-D, .65 for BAS-FS, .71 for RR, and .81 for BAS-Total. Retest reliabilities over an average of 1.8 months were r’s = .81 and .82, and stabilities over an average of 8.8 months were r’s = .70 and .60, for BIS and BAS-T, respectively.

Impulsivity

The Impulsive Nonconformity Scale (IN; Chapman et al., 1984) consists of 51 true/false items that tap impulsive behavior. Items include, “When I want something, delays are unbearable” and “I avoid trouble whenever I can” (reverse-scored). The IN scale has good internal consistency (αs = .79–.84; Alloy et al., 2006; Chapman et al., 1984) and 6-week retest reliability (r = .84; Chapman et al., 1984). In this study, α = .86. Chapman et al. (1984) found that high scorers on the IN were more likely to endorse antisocial, psychotic, depressive, and hypomanic/manic symptoms than a control group. Moreover, higher IN scores predicted prospective substance abuse problems in individuals with bipolar spectrum disorders and mediated bipolar disorder – substance abuse comorbidity (Alloy et al., 2009c) and a greater likelihood of arrests among bipolar II participants (Akiskal et al., 2003). Finally, Nusslock et al. (2008) found that higher IN scores combined with higher BAS sensitivity scores predicted greater academic impairment among individuals with bipolar spectrum disorders. In the LIBS Project sample, IN scores correlated r = .41 (p < .001) with BAS-Total scores, corresponding to 16.81% shared variance (Alloy et al., 2009c). Thus, BAS and IN appear to measure sufficiently distinct constructs.

Data Analysis Approach

Initial descriptive analyses were conducted to determine the mean and median age at onset of participants’ bipolar spectrum disorders, the proportion with a positive family history of bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives, the proportion who sought treatment for mood symptoms during the 4.5 year follow-up, and their means and standard deviations (SDs) on BIS, BAS, and IN. Rates of conversion to bipolar I disorder were also calculated among the entire bipolar spectrum group, and rates of conversion to bipolar II disorder were calculated for the 57 participants with initial cyclothymia or BiNOS diagnoses.

To examine predictors of conversion to more severe diagnoses, we conducted a series of hierarchical logistic regression analyses with either conversion (yes/no) to bipolar I disorder (onset of a manic/mixed episode) among the entire bipolar group or conversion (yes/no) to bipolar II disorder (onset of an MDE and hypomanic episode) among the initially cyclothymic/BiNOS participants as the dependent variables. In each logistic regression, length of follow-up (in days) was entered in Step 1 to control for opportunity to convert to a more severe diagnosis, baseline depressive (BDI) and hypomanic (HMI) symptoms were entered in Step 2 to account for any effects of baseline symptomatology on the prospective occurrence of mood episodes, treatment-seeking status during follow-up (yes/no) was entered in Step 3 to control for the possibility that treatment might affect the likelihood of progression to a more severe diagnosis, and a predictor of interest (e.g., age at onset, BAS score, IN score) was entered in Step 4. Whenever BAS-Total scores predicted conversion to bipolar I or II disorder, we examined the three BAS subscales separately to determine which were most responsible for the predictive association. For significant predictors of progression to a more severe diagnosis, we re-ran the hierarchical logistic regression analysis also including family history of bipolar disorder as a fifth covariate to provide an even more conservative test of the hypotheses. Finally, we also tested whether the interaction between BIS and BAS sensitivities predicted conversion to bipolar I disorder, by including the BIS × BAS interaction in the last step of the bipolar I logistic regression analysis.

Results

Descriptive Findings

The mean age of first onset of bipolar spectrum disorder (i.e., bipolar II, cyclothymia, or BiNOS) for the entire bipolar spectrum group was 13.0 (SD = 4.5 years; median age = 14.0). Forty-four (21.9%) of the 201 bipolar spectrum participants had a positive family history of bipolar spectrum disorders among first-degree relatives, and 142 (70.6%) sought treatment for mood symptoms at some time during the 4.5 year follow-up. Means and SDs of BIS/BAS and IN scores for the bipolar spectrum group were: BIS (M = 20.83, SD = 3.85), BAS-T (M = 40.64, SD = 5.18), and IN (M = 17.43, SD = 8.30).

Conversion Rates

Of 57 participants with cyclothymia or BiNOS at project outset, 24 (42.1%) converted to a bipolar II diagnosis over the follow-up, whereas 6 (10.5%) converted to a bipolar I diagnosis. Of 144 participants with bipolar II at project outset, 25 (17.4%) converted to a bipolar I diagnosis over the follow-up. Combining the cyclothymia/BiNOS and bipolar II participants, 31 out of 201 (15.4%) converted to a bipolar I diagnosis (28 with manic episode; 3 with mixed episode) during the follow-up. Of the 31 participants who converted to bipolar I, 4 were hospitalized for mania, 22 exhibited psychotic symptoms (including the 4 hospitalized), and another 9 showed other evidence of grave impairment (e.g., 3-year prison sentence, arrested and/or jailed, serious fights causing physical injury, spontaneous trip far away with no clothes or money, $12,000 shopping spree). For comparison, none of the healthy controls developed either bipolar I or II disorder over the follow-up and only 4 of 208 (1.9%) had an onset of a hypomanic episode during the follow-up.

Predictors of Conversion to Bipolar II Disorder

Table 1 summarizes the hierarchical logistic regression findings for predictors of progression to bipolar II disorder among participants with cyclothymia or BiNOS diagnoses at project outset. The number of days followed in the study (p = .338), baseline depressive symptoms (BDI scores, p = .508), baseline hypomanic symptoms (HMI scores, p = .197), and treatment-seeking status (p = .180) did not predict the likelihood of conversion to bipolar II disorder significantly. Controlling for these 4 covariates, neither age at onset nor family history of bipolar spectrum disorders predicted conversion to bipolar II significantly (see Table 1). Similarly, neither BIS sensitivity nor impulsivity predicted conversion to bipolar II disorder (see Table 1). However, higher BAS sensitivity (BAS-T scores) showed a nonsignificant trend to predict conversion to bipolar II disorder, controlling for days in study, BDI and HMI scores, and treatment-seeking (Wald = 3.445, p = .063, OR = 1.119, 95% CI = 0.994 – 1.261). This was primarily attributable to the Fun-Seeking subscale, as this was the only BAS subscale that significantly predicted conversion to bipolar II disorder, controlling for the covariates (Wald = 5.345, p = .021, OR = 1.401, 95% CI = 1.053 – 1.865). When family history of bipolar spectrum disorders was added as a fifth covariate, higher BAS-Total (Wald = 5.011, p = .025, OR = 1.163, 95% CI = 1.019 – 1.326) and higher Fun-Seeking (Wald = 5.866, p = .015, OR = 1.441, 95% CI = 1.072 – 1.938) predicted a greater likelihood of conversion to bipolar II disorder significantly.

Table 1.

Hierarchical Logistic Regressions Predicting Likelihood of Conversion to Bipolar II Disorder Among Participants with Cyclothymia or BiNOS (n = 57) Controlling for Length of Follow-up, Initial Depressive and Hypomanic/Manic Symptoms, and Treatment-Seeking Status

| Predictor | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Onset | 0.001 | .974 | 1.002 | 0.894 – 1.122 |

| Fam Hx BSD | 1.610 | .204 | 2.987 | 0.551 – 16.191 |

| BIS | 0.208 | .649 | 1.037 | 0.888 – 1.210 |

| BAS-T | 3.445 | .063 | 1.119 | 0.994 – 1.261 |

| BAS-Drive | 0.943 | .331 | 1.131 | 0.882 – 1.451 |

| BAS-FS | 5.345 | .021 | 1.401 | 1.053 – 1.865 |

| BAS-RR | 1.486 | .223 | 1.211 | 0.890 – 1.649 |

| IN | 0.909 | .340 | 1.052 | 0.947 – 1.169 |

Odds ratios (OR) less than 1.0 indicate a negative association between the predictor and conversion to bipolar II disorder. CI = Confidence Interval; Fam Hx BSD = family history of bipolar spectrum disorder; BIS = Behavioral Inhibition System scores; BAS-T = Behavioral Approach System – Total scores; BAS-Drive = BAS Drive subscale; BAS-FS = BAS Fun-Seeking subscale; BAS-RR = BAS Reward Responsiveness subscale; IN = Impulsive Nonconformity Scale.

Predictors of Conversion to Bipolar I Disorder

Table 2 provides a summary of the hierarchical logistic regression results for predictors of progression to bipolar I disorder among the entire bipolar spectrum group. Although baseline HMI scores (p = .245) and treatment-seeking status (p = .446) did not predict conversion to bipolar I disorder, more days followed in the study (Wald = 5.410, p = .020, OR = 1.001, 95% CI = 1.000 – 1.002) and higher BDI scores (Wald = 5.386, p = .020, OR = 1.049, 95% CI = 1.007 – 1.092) both significantly predicted a greater likelihood of conversion to bipolar I disorder. As shown in Table 2, controlling for these 4 covariates, earlier age at onset of bipolar spectrum disorder significantly predicted conversion to bipolar I (Wald = 12.579, p = .000, OR = .835, 95% CI = .756 – .923), whereas family history of bipolar spectrum disorders did not (p = .775). Earlier age of onset continued to predict conversion to bipolar I with family history of bipolar spectrum disorder added as a fifth covariate (Wald = 7.984, p = .005, OR = .859, 95% CI = .773 – .954).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Logistic Regressions Predicting Likelihood of Conversion to Bipolar I Disorder Among Participants with Bipolar II, Cyclothymia, or BiNOS (n = 201) Controlling for Length of Follow-up, Initial Depressive and Hypomanic/Manic Symptoms, and Treatment-Seeking Status

| Predictor | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Onset | 12.579 | .000 | 0.835 | 0.756 – 0.923 |

| Fam Hx BSD | 0.082 | .775 | 1.181 | 0.378 – 3.688 |

| BIS | 1.368 | .242 | 0.934 | 0.833 – 1.047 |

| BAS-T | 4.228 | .040 | 1.097 | 1.004 – 1.199 |

| BAS-Drive | 2.193 | .139 | 1.154 | 0.955 – 1.395 |

| BAS-FS | 4.273 | .039 | 1.244 | 1.011 – 1.530 |

| BAS-RR | 0.992 | .319 | 1.122 | 0.894 – 1.409 |

| IN | 6.310 | .012 | 1.080 | 1.017 – 1.148 |

| BIS × BAS | 4.292 | .038 | 1.024 | 1.001 – 1.048 |

Odds ratios (OR) less than 1.0 indicate a negative association between the predictor and conversion to bipolar I disorder. CI = Confidence Interval; Fam Hx BSD = family history of bipolar spectrum disorder; BIS = Behavioral Inhibition System scores; BAS-T = Behavioral Approach System – Total scores; BAS-Drive = BAS Drive subscale; BAS-FS = BAS Fun-Seeking subscale; BAS-RR = BAS Reward Responsiveness subscale; IN = Impulsive Nonconformity Scale.

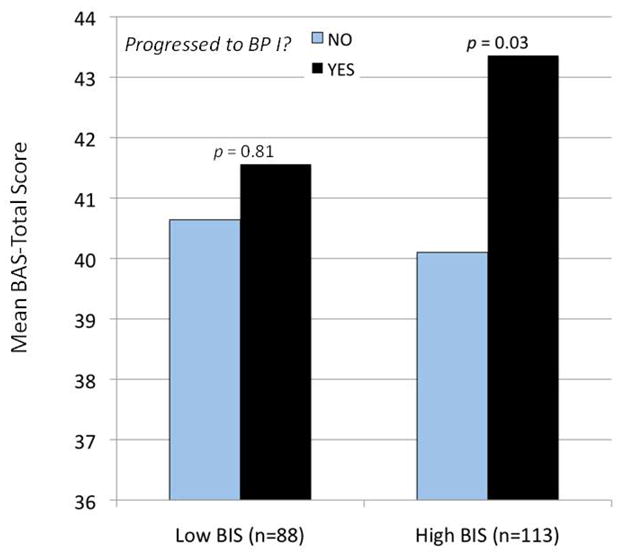

With respect to the personality variables, BIS sensitivity did not predict conversion to bipolar I significantly (p = .242), but higher BAS sensitivity (BAS-T scores) and higher impulsivity (IN scores) did predict progression to bipolar I controlling for the covariates (Wald = 4.228, p = .040, OR = 1.097, 95% CI = 1.004 – 1.199 for BAS-T; Wald = 6.310, p = .012; OR = 1.080, 95% CI = 1.017 – 1.148 for IN). The BAS sensitivity effect again was primarily attributable to the Fun-Seeking subscale, which predicted progression to bipolar I significantly (Wald = 4.273, p = .039, OR = 1.244, 95% CI = 1.011 – 1.530), whereas BAS Drive and Reward Responsiveness did not predict significantly (see Table 2). With family history added as a fifth covariate, impulsivity continued to predict conversion to bipolar I significantly (Wald = 7.100, p = .008, OR = 1.101, 95% CI = 1.026 – 1.182), but BAS-T and Fun-Seeking no longer predicted (p’s < .220). Finally, when added on the final step of the regression analysis, the BIS × BAS-T interaction did significantly predict progression to bipolar I disorder (Wald = 4.292, p < .038, OR = 1.024, 95% CI = 1.001 – 1.048). Figure 1 shows the pattern of this interaction. The influence of high BAS sensitivity on progression to a bipolar I diagnosis was more pronounced among bipolar spectrum individuals who also exhibited high levels of BIS sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Likelihood of progression to bipolar I disorder (yes = black bars; no = gray bars) as a function of BAS-Total (BAS-T) scores and low versus high (based on a median split) BIS scores.

Discussion

The present prospective, longitudinal study examined rates of conversion to more severe bipolar diagnoses (bipolar II and I disorder) among college-age individuals with “soft” bipolar conditions and high GBI scores. We also examined age of onset, BAS and BIS sensitivities, and impulsivity as predictors of conversion to more severe diagnoses in this large, non-patient sample of adolescents and young adults with childhood or adolescent onset of bipolar spectrum disorders. We found that 42.1% of individuals with cyclothymia or BiNOS progressed to a bipolar II diagnosis (had an onset of at least one MDE and one hypomanic episode) and 10.5% progressed to a bipolar I diagnosis (had an onset of at least one manic or mixed episode) over 4.5 years of follow-up. Among participants with a bipolar II diagnosis at the outset, 17.4% progressed to bipolar I over the follow-up. Our rates of conversion to bipolar I disorder among our bipolar II participants are more consistent with Birmaher et al.’s (2006 (2009) conversion rates (20–25%) to bipolar I disorder among youth with bipolar II disorder than they are with the lower rates of conversion to bipolar I disorder among adults with bipolar II (5 – 7.5%; Coryell et al., 1995; Joyce et al., 2004; Regeer et al., 2006). Similarly, our rates of conversion to bipolar II disorder among our cyclothymic and BiNOS participants (42.1%) were also generally consistent with rates of conversion to bipolar II disorder in the Kochman et al. (2005) study of youth (63.8%) and to bipolar II and I disorders in the Birmaher et al. (2009) study of youth with BiNOS diagnoses (38%). The general consistency of our conversion rates with those of studies of youth with “soft” bipolar conditions may be related to the fact that our sample of bipolar spectrum participants also had childhood or adolescent onset of their “soft” bipolar disorders (mean age of onset = 13; SD = 4.5 years) and were late adolescents/early adults at the outset of our study. Our conversion rates to more severe bipolar disorders may be higher than those of Lewinsohn et al’s (2000 (2003) community sample of adolescents for three reasons: We included participants with high GBI scores who may have been at higher risk for bipolar disorders, we used a higher threshold for identifying participants with bipolar spectrum diagnoses, and we had more frequent (every 4 months) prospective assessments of bipolar symptomatology and episodes than did Lewinsohn and colleagues, allowing for greater sensitivity in detecting onsets of MD and manic episodes signaling conversion to a more severe diagnosis.

That rates of conversion to more severe bipolar diagnoses in our sample and other samples of youth with “soft” bipolar disorders appear to be higher than those of adult samples with “soft” bipolar conditions suggests that early age of onset of bipolar spectrum disorders is a risk factor for a worse prognosis and higher rates of progression to more severe diagnoses (Beesdo et al., 2009; Birmaher et al., 2006; 2009; Kochman et al., 2005). Consistent with this possibility, we found that even among our participants with childhood or adolescent onset of bipolar spectrum disorders, an earlier age of onset was a significant predictor of higher rates of conversion to bipolar I (but not bipolar II) disorder (onset of a manic or mixed episode) in our sample, controlling for length of follow-up, baseline depressive and hypomanic symptoms, and treatment-seeking. Moreover, earlier age of onset remained a significant predictor of higher likelihood of conversion to bipolar I when family history of bipolar spectrum disorders was also controlled in the analyses. This suggests that the association between earlier age of onset and progression to bipolar I disorder is not simply attributable to early age of onset representing a proxy for greater familial loading for bipolar disorder. Perhaps, instead, early age of onset reflects a more severe underlying bipolar psychopathology, which leads both to earlier initial appearance of bipolar symptoms and greater likelihood of progressing to full-blown bipolar I.

In addition to examining cyclothymia/BiNOS diagnoses and early age of onset as risk factors for progression to more severe bipolar diagnoses, this study was the first to examine the theory-derived predictors of high BAS sensitivity and impulsivity as potential predictors of conversion to more severe bipolar diagnoses. According to the BAS model of bipolar spectrum disorders (Alloy & Abramson, 2010; Alloy et al., 2009a; Urosevic et al., 2008), high BAS sensitivity is a vulnerability for both initial onset and a more severe course of bipolar disorder. Consistent with the BAS model, we found that higher BAS sensitivity predicted greater likelihood of conversion to bipolar I diagnoses and showed a nonsignificant trend to predict to bipolar II diagnoses, controlling for length of follow-up, baseline depressive and hypomanic symptoms, and treatment-seeking. Given that the odds ratios for BAS sensitivity’s prediction of conversion to bipolar II and bipolar I diagnoses were very similar in magnitude, the trend association between BAS sensitivity and conversion to bipolar II disorder may be due to low statistical power in predicting progression to bipolar II in the much smaller cyclothymic/BiNOS group. When family history of bipolar spectrum disorders was included as a fifth covariate, BAS sensitivity predicted conversion to bipolar II disorder significantly, but no longer predicted conversion to bipolar I disorder. It is important to note that controlling for family history of bipolar disorder in addition to length of follow-up, treatment-seeking, and baseline mood symptoms is a very conservative test of the BAS sensitivity hypothesis. Thus, our results partially support the hypothesis that high BAS sensitivity is a risk factor for a worsening course of bipolar spectrum disorder, with a greater likelihood of progression to a more severe diagnosis. As such, our findings also support the concept of a bipolar spectrum – a set of disorders with similar underlying vulnerability and psychopathology that differ in severity.

In particular, the Fun-Seeking subscale was primarily responsible for the predictive association of BAS sensitivity with progression to both bipolar II and bipolar I diagnoses. Whereas BAS Drive assesses persistence in goal striving and BAS Reward Responsiveness assesses responsiveness to obtained rewards (or consummatory, postgoal positive affect), the BAS Fun-Seeking subscale assesses the component of BAS sensitivity relating to willingness to approach new and potentially rewarding experiences (e.g., “I’m always willing to try something new if I think it will be fun” and “I crave excitement and new sensations”). It is the subscale most related to impulsivity. In this regard, BAS Fun-Seeking’s predictive association with progression to more severe bipolar disorders is also consistent with our finding that impulsivity as measured by the Impulsive Nonconformity (IN) Scale also predicted conversion to bipolar I disorder significantly, controlling for all the covariates including family history of bipolar spectrum disorders. The BAS Fun-Seeking scale emphasizes the fun, reward-seeking subcomponent of impulsivity, whereas the IN scale assesses the broader concept of impulsivity, including the non-conforming, maladaptive component of impulsivity (e.g., “I break rules just for the hell of it” and “I always let people know how I feel about them, even if it hurts them a little”). Thus, it may not be surprising that IN predicts only to conversion to bipolar I disorder (onset of mania), and not to bipolar II (onset of major depression and hypomania). As suggested in the introduction, mania is primarily differentiated from hypomania by the presence of impairment, and nonconforming impulsivity may be especially relevant to predicting risky, impairing behaviors seen in mania.

We also found that the interaction of BIS and BAS sensitivities predicted progression to bipolar I disorder, such that the effect of high BAS sensitivity was more pronounced among bipolar spectrum individuals who were also high in BIS sensitivity. This finding is inconsistent with Gray’s (1991) hypothesis that mania (bipolar I) is characterized by high BAS plus low BIS. Instead, we found that bipolar spectrum individuals high in both motivational traits were most likely to progress to bipolar I. Given that high BIS sensitivity has been related to proneness to depression (e.g., Johnson, Turner & Iwata, 2003; Kasch, Rottenberg, Arnow, & Gotlib, 2002; Meyer et al., 1999; 2001) and high BAS sensitivity to mania, perhaps individuals in the bipolar spectrum high in both BIS and BAS sensitivities are particularly vulnerable to severe bipolar disorder (i.e., bipolar I). This finding will need to be replicated in future longitudinal studies of progression to bipolar I disorder.

Our findings have important clinical implications. They suggest that early age of onset, high BAS sensitivity, and high impulsivity may be indicators of a more severe course of bipolar disorder, with increased likelihood of progression to more severe diagnoses in the spectrum. As such, assessment of these predictors may be warranted with accompanying early intervention efforts when these predictors are present.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This investigation has several significant strengths. These include the inclusion of a large non-patient sample of individuals with “soft” bipolar spectrum disorders, a prospective longitudinal design, use of standardized diagnostic interviews and criteria, prospective diagnostic interviewers blind to the predictors of interest, frequent assessment intervals providing sufficient sensitivity for assessing depressive, hypomanic, and manic symptoms, and highly conservative statistical tests of the study hypotheses. Moreover, this is one of very few studies of predictors of progression along the bipolar spectrum to more severe disorders.

Despite these strengths, it is important to acknowledge this study’s limitations as well. First, although our study sample was a non-patient sample, it included university students, who, although ethnically and socioeconomically diverse, may not be representative of all non-patient samples. Further studies examining predictors of progression to more severe bipolar disorders are needed in other non-patient samples of individuals with “soft” bipolar conditions. Second, age of onset was assessed retrospectively and family history of bipolar spectrum disorders was assessed via the family history method rather than the more accurate family study method involving direct interviews of relatives. Third, we only assessed BAS sensitivity (the trait-like propensity to experience BAS activation and deactivation) and not changes in levels of BAS activation and deactivation themselves. Future studies should also examine the role of changes in BAS activation in predicting progression to more severe bipolar disorders. Fourth, BIS and BAS sensitivities and impulsivity were assessed with self-report instruments only. Although the self-report measures are reliable and valid assessments of these constructs, future tests of predictors of progression to more severe disorders in the bipolar spectrum may benefit from behavioral and psychophysiological (e.g., EEG) assessments of these constructs as well.

Conclusions

In summary, this study is one of the few longitudinal studies of rates and predictors of progression to more severe bipolar diagnoses in a large, non-patient sample of individuals with childhood or adolescent onset of “soft” bipolar conditions, and it is the only study to examine the theoretically-derived predictors of BAS sensitivity and impulsivity. Our findings support the concept of a bipolar spectrum in that a sizable proportion of participants with “soft” bipolar conditions converted to more severe bipolar I and II diagnoses during an average of 4.5 years of follow-up, with conversion rates consistent with previous studies of samples of children and adolescents with “soft” bipolar conditions. Moreover, our findings provide some support for the BAS model of bipolar disorders (Alloy & Abramson, 2010; Alloy et al., 2009a, b, c; Urosevic et al., 2008) and suggest that high BAS sensitivity and impulsivity may be an important part of the vulnerability that underlies the entire bipolar spectrum.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH52617 and MH77908 to Lauren B. Alloy and MH52662 to Lyn Y. Abramson.

Footnotes

Decisions about whether another comorbid disorder was primary or secondary to a bipolar disorder were made in consensus meetings with senior diagnosticians and psychiatrist consultation based on all available information including: whether the bipolar disorder or other disorder had an earlier age of onset; the number of bipolar symptoms not explainable by the other disorder, and behavioral evidence of the bipolar symptoms in the participant’s life.

Contributor Information

Lauren B. Alloy, Temple University

Snežana Urošević, University of Minnesota.

Lyn Y. Abramson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Shari Jager-Hyman, Temple University.

Robin Nusslock, Northwestern University.

Wayne G. Whitehouse, Temple University

Michael Hogan, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

- Akiskal HS, Djenderedjian AH, Rosenthal RH, Khani MK. Cyclothymic disorder: Validating criteria for inclusion in the bipolar affective group. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1977;134:1227–1233. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.11.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiskal HS, Hantouche EG, Allilaire JF. Bipolar II with and without cyclothymic temperament: “dark” and “sunny” expressions of soft bipolarity. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;73:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY. The role of the Behavioral Approach System (BAS) in Bipolar spectrum disorders. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:189–194. doi: 10.1177/0963721410370292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Urosevic S, Bender RE, Wagner CA. Longitudinal predictors of bipolar spectrum disorders: A Behavioral Approach System (BAS) perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009a;16:206–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Gerstein RK, Keyser JD, Whitehouse WG, et al. Behavioral Approach System (BAS) – relevant cognitive styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Concurrent and prospective associations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009b;118:459–471. doi: 10.1037/a0016604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Bender RE, Wagner CA, Whitehouse WG, Abramson LY, Hogan ME, et al. Bipolar spectrum – substance use co-occurrence: Behavioral Approach System (BAS) sensitivity and impulsiveness as shared personality vulnerabilities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009c;97:549–565. doi: 10.1037/a0016061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Cogswell A, Grandin LD, Hughes ME, et al. Behavioral Approach System and Behavioral Inhibition System sensitivities: Prospective prediction of bipolar mood episodes. Bipolar Disorders. 2008;10:310–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Cogswell A, Smith J, Hughes M, et al. Behavioral Approach System (BAS) sensitivity and bipolar spectrum disorders: A retrospective and concurrent behavioral high-risk design. Motivation and Emotion. 2006;30:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Reilly-Harrington NA, Fresco DM, Whitehouse WG, Zechmeister JS. Cognitive styles and life events in subsyndromal unipolar and bipolar mood disorders: Stability and prospective prediction of depressive and hypomanic mood swings. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 1999;13:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual. 4. Washington, D.C.: Author; 2000. Text Revised. [Google Scholar]

- Andreason N, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria: Reliability and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1977;34:1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini RJ. A plea for integrity of the bipolar disorder concept. Bipolar Disorders. 2000;2:3–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Hofler M, Leibenluft E, Lieb R, Bauer M, Pfenning A. Mood episodes and mood disorders: Patterns of incidence and conversion in the three decades of life. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11:637–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellivier F, Golmard J, Henry C, Leboyer M, Schurhoff F. Admixture analysis of age at onset in bipolar I affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:510–512. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellivier F, Golmard J, Rietschel M, Schulze TG, Malafosse A, Preisig M, et al. Age of onset in bipolar I affective disorder: Further evidence for three subgroups. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:999–1001. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Dodd S, Callaly P, Berk L, Fitzgerald P, de Castella AR, et al. History of illness prior to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;103:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, Strober M, Gill MK, Hunt J, et al. Four- year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: The Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:795–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:175–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Numbers JS, Edell WS, Carpenter BN, Beckfield D. Impulsive nonconformity as a trait contributing to the prediction of psychotic-like and schizotypal symptoms. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1984;172:681–691. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198411000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, Keller MB, Leon AC, Akiskal HS. Long-term stability of polarity distinctions in the affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:385–390. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Gullo MJ, Loxton NJ. Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: Implications for substance misuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1389–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Iacono WG. Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Reviews in Psychology. 1989;40:457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Krauss S, Spoont MR. A two-dimensional threshold model of seasonal bipolar affective disorder. In: Magnusson D, Ohman A, editors. Psychopathology: An interactional perspective. New York: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Krauss S, Spoont MR, Arbisi P. General behavioral inventory identification of unipolar and bipolar affective conditions in a nonclinical university population. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:117–126. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Slater J, Wolfstetter-Kausch H, Klein D, Goplerud E, Farr D. A behavioral paradigm for identifying persons at risk for bipolar depressive disorder: A conceptual framework and five validation studies (Monograph) Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90:381–437. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.5.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M. BIS/BAS scores are correlated with frontal EEG asymmetry in intrusive and withdrawn depressed mothers. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:665–675. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: The schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Neural systems, emotion and personality. In: Madden J, editor. Neurobiology of learning, emotion, and affect. New York: Raven Press; 1991. pp. 273–306. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt LJ, Abramson LY. The Halberstadt Mania Inventory (HMI): A self-report measure of manic/hypomanic symptomatology. University of Wisconsin; 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Abramson LY, Nusslock R, Sigelman JD, Urosevic S, Turonie LD, et al. Effect of bipolar disorder on left frontal cortical responses to goals differing in valence and task difficulty. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:693–698. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Allen JJB. Behavioral activation sensitivity and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: Covariation of putative indicators related to risk for mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:159–163. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden EP, Bodkins M, Brenner C, Shekhar A, Nurnberger JI, O’Donnell BF, et al. A multimethod investigation of the Behavioral Activation System in bipolar disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:164–170. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Cueller AK, Ruggero C, Winett-Perlman C, Goodnick P, White R, et al. Life events as predictors of mania and depression in bipolar I disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:268–277. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Sandrow D, Meyer B, Winters R, Miller I, Solomon D, et al. Increases in manic symptoms after life events involving goal attainment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:721–727. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Turner RJ, Iwata N. BIS/BAS levels and psychiatric disorder: An epidemiological study. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavior Assessment. 2003;25:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce PR, Luty SE, McKenzie JM, Mulder RT, McIntosh VV, Carter FA, Bulik CM, Sullivan PF. Bipolar II disorder: Personality and outcome in two clinical samples. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;38:433–438. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, Gotlib IH. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:589–597. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochman FJ, Hantouche EG, Ferrari P, Lancrenon S, Bayart D, Akiskal HS. Cyclothymic temperament as a prospective predictor of bipolarity and suicidality in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;85:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. Edinburgh, Scotland: Livingstone; 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Kwapil TR, Miller MB, Zisner MC, Chapman LJ, Chapman J, Eckblad M. A longitudinal study of high scorers on the Hypomanic Personality Scale. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Wright K, Smith N. Dysfunctional assumptions in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;79:193–199. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: Prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:454–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorder during adolescence and young adulthood in a community sample. Bipolar Disorders. 2000;2:281–293. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Klein DN. Bipolar disorder during adolescence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108(Suppl 418):47–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, Sham P, Katz R, Cardno A. The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:497–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Chakravarti A, Moldin SO, Araj H, Blangero JC, Burmeister M, et al. Future of genetics of mood disorders research. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:457–477. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, Johnson SL, Carver CS. Exploring behavioral activation and inhibition sensitivities among college students at risk for bipolar spectrum symptomatology. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1999;21:275–292. doi: 10.1023/A:1022119414440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, Johnson SL, Winters R. Responsiveness to threat and incentive in bipolar disorder: Relations of the BIS/BAS scales with symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23:133–143. doi: 10.1023/A:1010929402770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslock R, Abramson LY, Harmon-Jones E, Alloy LB, Hogan ME. A goal-striving life event and the onset of bipolar episodes: Perspective from the Behavioral Approach System (BAS) dysregulation theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:105–115. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslock R, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Harmon-Jones E, Hogan ME. Impairment in the achievement domain in bipolar spectrum disorders: Role of Behavioral Approach System (BAS) hypersensitivity and impulsivity. Minerva Pediatrica. 2008;60:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Ostacher M, DelBello MP, et al. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: Data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeger EJ, Krabbendam L, De Graaf R, Ten Have M, Nolen WA, Van Os J. A prospective study of the transition rates of subthreshold (hypo)mania and depression in the general population. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:619–627. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salavert J, Caseras X, Torrubia R, Furest S, Arranz B, Duenas R, et al. The functioning of the Behavioral Activation and Inhibition Systems in bipolar I euthymic patients and its influence in subsequent episodes over an 18-month period. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:1323–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Stanton B, Garland A, Ferrier IN. Cognitive vulnerability in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:467–472. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J. Biometrics Research. New York: State Psychiatric Institute; 1978. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia – Change Version. [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Schmidt-Lackner S, Freeman R, Bower S, Lampert C, DeAntonio M. Recovery and relapse in adolescents with bipolar affective illness: A five-year naturalistic, prospective follow-up. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:724–731. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton SK, Davidson RJ. Prefrontal brain asymmetry: A biological subtrate of the behavioral approach and inhibition systems. Psychological Science. 1997;8:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Dougherty DM, Pazzaglia P, Pham M, Moeller FG. Impulsivity: A Link between bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:204–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Dougherty DM, Pazzaglia P, Pham M, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG. Increased impulsivity associated with severity of suicide attempt history in patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1680–1687. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Moeller FG, Steinberg JL, Schneider L, Barrat ES, Dougherty DM. Manic symptoms and impulsivity during bipolar depressive episodes. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9:206–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urošević S, Abramson LY, Harmon-Jones E, Alloy LB. Dysregulation of the behavioral approach system (BAS) in bipolar spectrum disorders: Review of theory and evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1188–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.