Abstract

This paper describes the efforts of the St. Louis Personality and Aging Network (SPAN) team to increase participation by African American men in our study. Initially, African American men were participating at a rate far lower than both European American men and women and African American women. Two years into the study, the SPAN team constructed a letter targeted towards African American men that specifically requested their participation in the study. This letter was mailed to households in various areas of the city heavily populated by African Americans. As a result of this letter and other enhancement strategies, the proportion of men in our African American sample increased from 31% to 43% (71 African American men were recruited in the first two years of the study, compared to 147 recruited in the year-and-a-half after the letter was distributed). Other strategies to recruit and retain African American men in mental health studies are also highlighted.

Keywords: African American men, epidemiology, personality, recruitment, response bias

Recruiting African American men as research participants has been extensively documented (e.g., Freimuth et al., 2001; Milburn et al., 1991; Shavers, Lynch, & Burmeister, 2002; Thompson, Neighbors, Munday, & Jackson, 1996; Woods, Montgomery, Herring, 2004). Given the numerous health disparities affecting the African American community (e.g., access to health care, health outcomes, CDC, 2011), under-recruitment in health studies is of increasing concern (e.g., Murthy et al., 2004). According to a focus group study of African American men, simply being “invited…to participate in a research study” was enough to increase involvement in prostrate cancer prevention research (Woods et al., 2004). Additionally, feeling that their input was valued and that the research staff had a genuine interest in them were factors that would likely increase participation. Both African American men and women focus group attendees recommended a multi-modal consent process (e.g., video and written forms), time to think about participating, and contact information for study staff who would be willing to answer questions about medical research studies (Corbie-Smith et al., 1999).

This paper will describe how a psychological research team responded to the challenge of recruiting a sample of African American men to participate in a community-based study of personality, health, and transitions in middle-age and later life.

WHY IS RECRUITMENT CHALLENGING?

There are many reasons for the difficulties associated with recruiting African American research participants. Perhaps most important is the memory of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in which African American men who were infected with syphilis were recruited to participate in a study where they were told their “bad blood” would be treated. Instead medical doctors studied the “natural course” of the disease in these untreated men against their knowledge (CDC, 2009; Gamble, 1997; Killien et al., 2000). This experimental atrocity has left a lingering fear of research in the minds of many African Americans, especially men (Freimuth et al., 2001).

African Americans also shy away from participating in psychological research because of the stigma associated with mental illness. For many, the idea of being diagnosed with a mental illness or even associated with a study related to mental illness is shameful. This stigma is common across many racial/ethnic groups, but is especially strong within the African American community (Whaley, 2005).

Many African Americans find it difficult to believe that psychological research will provide any benefits to them believing instead that researchers may use them to further their own projects and goals (Thompson, Neighbors, Munday, & Jackson, 1996). By either not contributing to the community in return or not publicizing contributions, researchers unwittingly perpetuate the idea that psychological research holds value (or even applicability) solely to the researchers. While all IRB-approved studies are required to explain benefits and risks as part of their consent process, extra attention may need to be devoted to explaining these factors to populations who are not accustomed to participating in research studies, e.g., African Americans (Sinclair, 2000).

Finally, African American men are thought to exhibit what is known as the “black male health behavior phenomenon” which suggests that they are less likely to participate in health-related-research for the same reasons they may be less likely than other groups to go to doctors’ appointments (Woods et al., 2004).

METHODS

The St. Louis Personality and Aging Network (SPAN) study was designed to explore personality, health and transitions in later life among St. Louis community residents between the ages of 55 and 64 (see Oltmanns & Gleason, 2011 for a detailed description of the study). The original goal of the study was to obtain a sample that was ethnically representative of the metropolitan St. Louis area, city and suburbs combined (total population of approximately 2.8 million people). According to recent population statistics, this could be achieved with a sample composed of 60% European Americans, 30% African Americans, and 2% Hispanics.

Participants-Targeted Recruitment

Participants in the study were contacted using listed home phone numbers and the accompanying addresses (purchased from a sampling firm) of randomly selected households believed on the basis of recent census data to have at least one resident within our age range. These phone numbers were selected without regard to whether they were listed in a man’s or a woman’s name. Initial contact with participants was made via an official letter describing the goals and methods of the study. Next participants were called on the telephone for a thorough explanation of the study and to set up an appointment time if they agreed to participate. If more than one person in the household was in the designated age range, the Kish Method (1949) was used to identify the participant. Participants were offered $60 for their participation in the baseline assessment. All participants signed an informed consent statement.

Two years after the study began, it became clear that the participation rate was rather low for African American men. Among European American participants, 46% were men, but only 31% of our African American participants were men. In the St. Louis metropolitan area, 48% of the European American population are men and 42% of the African American population are men. Despite these ratio differences it was still necessary to increase the participation of African American men to approach population estimates (Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, 2011). Therefore we developed a more targeted approach for recruiting African American men which would run parallel with our general recruiting procedure. This new effort was aimed at households in areas of St. Louis known to have a high concentration of African Americans (based on census data provided by the sampling firm from which phone numbers were purchased). Ten zip codes were identified with percentages of African Americans ranging from 78–100%. Because this effort was designed to oversample African American men, only households in which the phone number was listed in a man’s name were selected.

Instruments

A letter was crafted geared towards African American men requesting their participation in the study. This letter was designed by lab staff with the help of an Emeritus professor of Psychology and African American Studies. The letter was simple in its description of the study and very similar to the letter mailed out in the initial recruitment phase. The last two sentences of the introductory paragraph in the targeted letter read “It is important that we collect information from all kinds of people. In particular we are concerned with including African American men.” Additionally, instead of indicating that a “household” had been selected for participation, the targeted letter stated that “your name was selected.” These sentences were the only direct appeal to the target population. The letters were mailed out in groups of 300 to households fitting the qualifications previously described. In total, 900 households received this letter. Mailings went out in June and September of 2009 and June of 2010.

As we began the targeted phase of recruitment, we placed a poster of full-time staff members, graduate students, undergraduate research assistants, and the principal investigator -including names and photographs- in the main entrance area of the lab offices. Our intention was to help participants see with whom they could expect to work while in the study, and also to display the cultural diversity of lab members. Permanent lab members include two African American women, two European American men, one Indian-American woman, and five European American women. There are also many undergraduate research assistants working in the lab at any given time, who are primarily European American but include several Asian and African American students as well.

Phone Calls

As in the project’s standard recruitment procedures, interested persons were asked to return a postcard or contact the SPAN lab at a phone number provided in the introductory letter. Anyone who did not return the card or call was called by lab staff for recruitment. If the person did not answer his phone after 12 calls had been placed a second letter was mailed, again asking him to return the postcard or call the lab. When a potential participant did answer the phone a lab staff member described the study, answered questions about study procedures, and scheduled appointments for interested persons. Whenever possible these calls were made by African American staff members or student research assistants.

RESULTS

The SPAN lab received 45 calls as a result of the targeted letters (5% positive response); 26 of these calls resulted in a scheduled appointment on the first phone call. The results of phone calls to all 900 households (including the 45 that initiated contact with us) can be found in Table 1. Overall 220 persons were never reached, 196 were ineligible (e.g., deceased, seriously ill, outside of age range), 194 declined participation, and 122 scheduled and completed appointments. As a result of this process, we also contacted some European American men who lived in the targeted areas. Eighteen of these men agreed to participate and were included in the study.

Table 1.

Status of households contacted in targeted phase of recruitment

| STATUS | HOUSEHOLDS (n=900) |

|---|---|

| Answering Machine | 24.4% |

| Not interested | 21.5% |

| Appointment completed | 13.5% |

| Disconnect phone | 12.5% |

| Not eligible | 21.7% |

| Missed Appointment (no-show) | 2% |

| Interested call back | 2% |

| Not African American | 2% |

| Appointment scheduled but not yet completed | 0.1% |

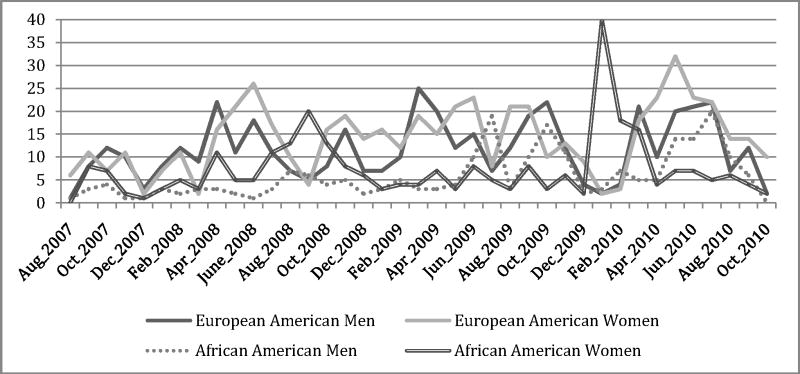

At the conclusion of baseline data collection, the SPAN study had enrolled approximately 1000 European Americans (45% men) and about 500 African Americans (43% men). The overall result of the targeted recruitment process was a substantial increase in the number of African American men recruited each month to the study. As can be seen in Figure 1, prior to the targeted phase of recruitment African American men were participating at a rate far lower than African American women, European American women, and European American men. After the targeted letter was mailed in June 2009, the average number of African American men recruited each month increased substantially from 3 to 8 per month.

Figure 1.

Monthly recruitment of SPAN study participants

DISCUSSION and CONCLUSIONS

This recruitment effort appeared to work because it addressed many of the concerns raised by previous investigators (e.g., Corbie-Smith et al.,1999;Woods et al., 2004). One involves the quality of the invitation to participate. The project’s standard recruitment letter is quite general and could have been interpreted by skeptical community residents as being less sincere. By altering a few sentences, we were able to make a direct appeal to the targeted population which seemed to be received as a more genuine invitation.

Focus group participants in other studies have indicated that it is important to feel a genuine interest from the study team. The SPAN team works hard to make each participant feel equally important. This is accomplished in several ways: meeting participants in the parking lot with a parking pass and walking them to the lab, offering refreshments throughout the assessment, encouraging participants to ask questions about the study at any time, and working with only one participant at a time, thus providing them with our undivided attention. Because each member of the SPAN team has achieved success using this approach to working with participants, we have not found it necessary to attempt matching African American interviewers with African American participants. Other researchers have found that obtaining a racial match between participant and interviewer is not particularly important to the comfort of the participant as long as the other efforts (e.g., demonstrate genuine interest) are in place (Freimuth et al., 2001; Woods et al., 2004).

In another attempt to be sensitive to the values of African American participants, phone callers were trained to refer to them by their last names (e.g., Mr./Mrs. Jones) until given permission to use their first names. This cultural difference is important and denotes respect for elders, which is a major component of African American culture.

One of the goals of a project like the SPAN study is to recruit a sample that accurately reflects the diversity of the community. Criticism leveled at community-based studies often suggests that the participants include people who are easy to reach and generally inclined to participate in research studies. The SPAN team has countered this argument within one demographic group: African American men. We were able to recruit persons who do not necessarily readily volunteer to be in research studies.

Beyond the problem of failing to obtain a desired sample are the issues of generalizability and increasing research on ethnic minorities (Yancey et al., 2006). Research samples that only include one group of people produce results that can only be applied to that same group. The lack of research relevant to ethnic minorities has been extensively documented (e.g., Iwamasa et al., 2000; Sue, 1999). Limiting data collection to samples of convenience and those that are recruited with minimal effort further contributes to the lack of good psychological science related to these populations. Because of the many health disparities affecting the African American community, it is imperative to increase their participation in research studies to learn more about this population.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This paper is concerned with recruitment of African American men to participate in a psychological research study. Because the SPAN study is longitudinal we are also concerned with effective retention strategies. Study staff makes sincere efforts to make all participants feel comfortable and valued (e.g., birthday and holiday cards are sent to participants each year.) While we have yet to devise specific retention strategies for African American men, we believe that our current efforts at engagement and transparency may suffice. Going forward, similar efforts may be required for other underrepresented groups (e.g., Hispanics and Asians).

While focus groups were not used in this study, other researchers have benefited from their use in the planning stages of their research projects. Talking openly about common recruitment challenges and gauging community interest promotes cultural sensitivity in research staff and begins to establish trust within the targeted community. In future research projects it may be helpful to organize focus groups at the outset to eliminate the need for a reorganization of recruitment efforts after the study has already begun.

Finally, our primary recruitment strategy involved speaking with participants on the telephone. Given that this study began in 2007, the increased reliance on cell phones as opposed to landlines may have impacted our ability to contact some persons. Based on sampling data provided by Genesys Sampling Systems, 98% of St. Louis residents in our age range have working landline telephones. Attempting contact via cell phones may prove useful in the future, although this is a less of a concern in this age range (Genesys Sampling Systems, personal communication, 2006).

Acknowledgments

We thank Merlyn Rodrigues, Amber Wilson, Rickey Louis, Andy Shields, Josh Oltmanns, several graduate students (Abby Powers, Erin Lawton, and Krystle Disney) and dozens of undergraduate volunteers. We also want to thank Robert Williams and Linda Cottler for their invaluable advice regarding recruitment procedures. Finally, we are especially grateful to hundreds of St. Louis residents who have given us hours of their time and shared their personal stories with us. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (RO-1 MH077840).

References

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14:537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. public health service syphilis study at Tuskegee. Retrieved June. 2009;13:2009. from www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.

- Freimuth VS, Quinn SC, Thomas SB, Cole G, Zook E, Duncan T. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee syphilis study. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:797–808. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamasa GY, Sorocco KH, Koonce DA. Ethnicity and clinical psychology: A content analysis of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:931–944. doi: 10.1016/SO272-7538(02)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killien M, Bigby JA, Champion V, Fernandez-Repollet E, Jackson RD, Kagawa-Singer M, Kidd K, Naughton MJ, Prout M. Involving minority and underrepresented women in clinical trials: The national centers of excellence in women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 2000;9:1061–1070. doi: 10.1089/152460900445974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1949;44:380–87. doi: 10.2307/2280236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn NG, Gary LE, Booth JA, Brown DR. Conducting epidemiologic research in a minority community: Methodological considerations. Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:3–12. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199101)19:1<3:AD-JCOP2290190102>3.0.C);2-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. Population mica. 2011 Table created and retrieved from http://dhss.mo.gov/data/mica/mica/population.php.

- Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;29:2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Gleason MEJ. Personality, health, and social adjustment in later life. In: Cottler LB, editor. Mental health in public health: The next 100 years. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12:248–256. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S. Recruiting African Americans for health studies: Lessons from the drew-rand center on health and aging. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2000;6:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. Science, ethnicity, and bias: Where have we gone wrong? American Psychologist. 1999;54:1070–1077. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.12.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EE, Neighbors HW, Munday C, Jackson JS. Recruitment and retention of African American patients for clinical research: An exploration of response rates in an urban psychiatric hospital. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:861–867. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and mortality weekly report: CDC health disparities and inequalities report-United States 2011. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/Mmwr/pdf/other/su6001.pdf.

- Whaley AL. Racial self-designation and disorder in african american psychiatric patients. Journal of Black Psychology. 2005;31:87–104. doi: 10.1177/0095798404270871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Herring RP. Recruiting black/African American men for research on prostate cancer prevention. American Cancer Society. 2004;5:1017–1025. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]