Abstract

Elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms of protein folding and function is a very exciting and active research area, but poses significant challenges. This is due in part to the fact that existing experimental techniques are incapable of capturing snapshots along the ‘reaction coordinate’ in question with both sufficient spatial and temporal resolutions. In this regard, recent years have seen increased interests and efforts in development and employment of site-specific probes to enhance the structural sensitivity of spectroscopic techniques in conformational and dynamical studies of biological molecules. In particular, the spectroscopic and chemical properties of nitriles, thiocyanates, and azides render these groups attractive for the interrogation of complex biochemical constructs and processes. Here, we review their signatures in vibrational, fluorescence and NMR spectra and their utility in the context of elucidating chemical structure and dynamics of protein and DNA molecules.

Keywords: Infrared probe, unnatural amino acid, nitrile stretching vibration, azide stretching vibration, spectral modeling

The free energy landscape of biomolecules, such as proteins, is a function of a large number of degrees of freedom. Thus, elucidating the structural dynamics of any protein with high spatial and temporal resolution is a difficult enterprise. In this regard, recent years have seen an increased interest in the utilization of various extrinsic molecular probes that can be incorporated into biomolecules in a site-specific manner to monitor, for example, the local electrostatics and dynamics of proteins and DNA. Herein, we offer our perspectives on this fast-growing field, with a focus on the recent development of unnatural amino acids as infrared (IR) environmental and/or structural reporters of proteins, especially those containing a nitrile, thiocyanate, or azide group. While other site-specific IR probes, such as those based on isotopic labeling, are also very useful in protein folding and conformational studies, they have been discussed and reviewed elsewhere.1-7 One of the advantages of using unnatural amino acid spectroscopic probes is that they often induce minimal perturbation to the protein structure in question and can be incorporated into the polypeptide sequence of interest using either in vitro or in vivo methods.8,9 Although the development of incorporation methods itself is a very active field, an extensive review of the recent advances in selectively and site-specifically incorporating unnatural amino acids into proteins is beyond the scope of this Perspective. Briefly, besides standard solid phase peptide synthesis or semi-synthesis methods,10,11 other in vitro methods include those via post-translational modification of a specific amino acid sidechain, such as cysteine,12-15 arginine,16 lysine,17 and tyrosine,18 whereas in vivo methods generally involve direct subcloning (e.g., green fluorescent protein fusions),19 suppressor tRNA modifications,20,21 and amino acid replacement techniques.22-24

Site-Specific Vibrational Probes

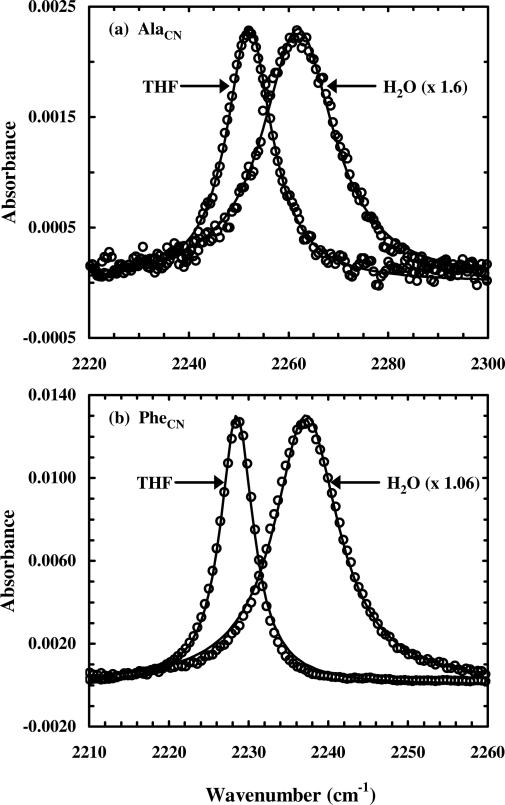

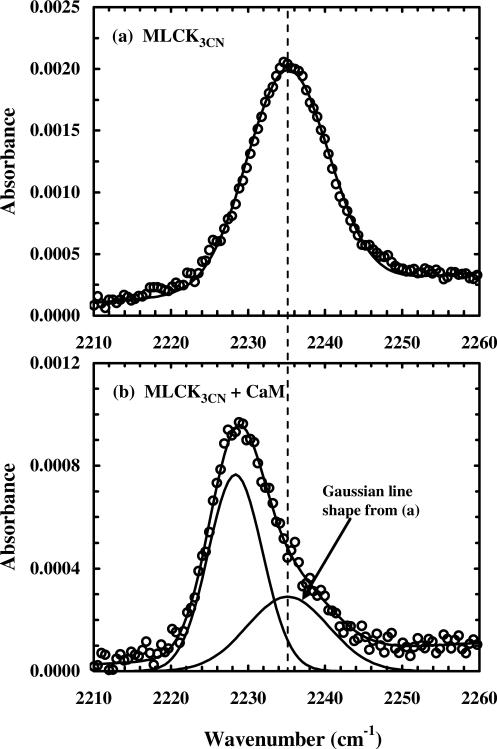

Vibrational transitions in condensed phases typically occur on ultrafast (fs−ps) timescales.25 Thus, time-resolved vibrational spectroscopy is capable of offering high temporal resolution in protein conformational studies. However, without introduction of a suitable and site-specific vibrational reporter, this technique is often limited to low structural resolutions. To overcome this limitation, many strategies have been developed to achieve site-specificity. One such strategy, which recently is becoming more widely used, is to employ unnatural amino acids that contain an environmentally (and hence structurally) sensitive and relatively strong vibrator (compared to the peak extinction coefficient of the amide I transition, 720 M-1cm-1). As pointed out by Getahun et al.,26 for a vibrational mode to be useful as a monitor of the local environment of proteins it should be a simple transition, largely decoupled from the rest of the molecule, and it should also have a relatively intense, narrow absorption band that is separated from other absorption bands of the molecule. An additional requirement, perhaps a more important one, is that the extrinsic vibrational probe should minimally perturb the conformation of the protein in question. Nitrile (C≡N) and azide (N3) moieties largely meet these criteria as their stretching vibrations not only have relatively high extinction coefficients, but are also well separated from other vibrational modes of proteins. In addition, these groups can serve as an atomic substitution within an amino acid sidechain (Table 1), thus minimizing any perturbative effects. For example, Getahun et al.26 have shown that nitrile-derivatized amino acids could be used as local IR environmental probes of proteins (Figures 1 and 2). Below, we will first discuss experimental investigations and theoretical modeling of the vibrational transitions of these probes, and then review specific examples of their applications in several representative biological and biophysical studies.

Table 1.

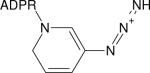

Overview of nitrile and azido probes.

| Name (Abbreviation) | Structure | Band Position (cm-1) (Band Width) | Intensity (M-1 cm-1)a (Solvent, Ref.) | Application (Ref.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | THF | ||||

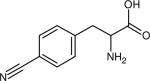

| Para-cyanophenylalanine (p-PheCN) |

|

2237.2 (9.8) | 2228.5b (5.0) | ~220 (THF, 26) | IR (26,146,147) Raman (144) Fluorescence (124,129) |

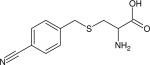

| Para-cyanobenzylcysteine (p-CysBCN) |

|

2236.6 (11.8) | 2228.5 (7.4) | 210 ± 60 (H2O, 15) | IR (15) |

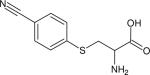

| Para-cyanophenylcysteine (p-CysPCN) |

|

2233.7 (11.2) | 2226.8 (6.1) | 240 ± 60 (H2O, 15) | IR (15) |

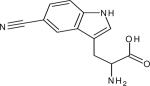

| 5 -cyanotryptophan (5-TrpCN) |

|

2224.6c (15.6) | 2220.4 (9.3) | ~450 (2-MeTHF at 74K, 57)d | IR (132) Fluorescence (132) |

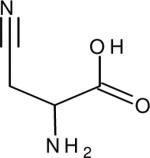

| Beta-cyanoalanine (β-AlaCN) |

|

2261.9 (18.2) | 2252.1b (11.0) | 32.2 (H2O, 26) | IR (26) |

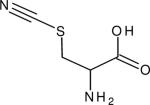

| Beta-Thiocyanatoalanine (β-AlaSCN) |

|

2162.0 (12.8) | ~2158 | 153.8 (H2O, 67) | IR (14,148,149) NMR (117) |

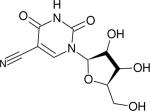

| 5 -Cyano-2’ deoxyuridine (dUCN) |

|

2241.9 (~11.5) | 2232.7 (8) | 332 (2-MeTHF at 74 K, 150) | IR (106,150) |

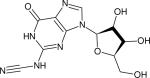

| N2-nitrile-2’-deoxyguanosine (dGCN) |

|

n.a. | 2170 (29)e | 412 (2-MeTHF at 74 K, 150) | IR (150) |

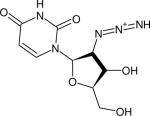

| 2’-Azido-2’-deoxyuridine (N3-dU) |

|

2124 (22) | 2110 (18) | 1160 ± 150 (H2O, 77) | IR (77,134) NMR (134) |

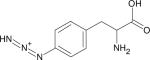

| Para-Azidophenylalanine (p-PheN3) |

|

~2128.6 | ~2115.5f | n.a. | IR (123,151) |

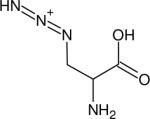

| Beta-Azidoalanine (β-AlaN3) |

|

2118.4 (27.8) | 2104.6 (25.6)g | 414 (H2O, 152) | IR (152,153) |

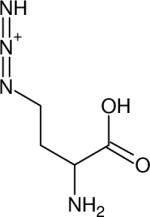

| Azidohomoalanine (Aha) |

|

2115 (~38) | 2098 (~38)h | 1570 (H2O, 127) | IR (127) |

| Azido-NAD+ |

|

2140 (33) | 2138 (26)i | 250 (H2O, 135) | IR (135,154) |

Peak extinction coefficient was estimated based on reported values of concentration and optical pathlength. The reader might find it useful to compare the coefficients with the one for the amide I vibration of 720 M-1cm-1 (Ref. 152)

measurements in THF were performed with the corresponding Fmoc-versions of the amino acids

measurements in water were performed in 95:5 mixture of water/methanol on 5-cyanoindole

5-cyanoindole

measured in 2-MeTHF

measured in isopropanol

measured in DMSO

measured in DMF

measured on FDH-azido-NAD+ complex in H2O.

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra (in the C≡N stretching region) of β-AlaCN and p-PheCN in H2O and Fmoc-β-AlaCN and Fmoc-p-PheCN in THF, as indicated (reproduced from Ref. 26 with permission).

Figure 2.

The C≡N stretching bands of a calmodulin (CaM) binding peptide (MLCK3CN) in the presence and absence of CaM, showing the sensitivity of this vibration to its environment (reproduced from Ref. 26 with permission).

Properties of the C≡N stretching mode of nitriles

The nitrile stretching band of a variety of nitrile compounds have been extensively studied in the gas27-31 and condensed32-63 phases. In particular, the solvent,41,43-45,47,48,50-52,59,60,62,63 temperature,44,45,49 pressure,32,51 electrostatic field,55-57 or complexation33,34,36-40,46,64,65 induced vibrational frequency shifts from a reference value and intensity changes of this normal mode have been the focus of many previous investigations. For example, the nitrile stretching band of acetonitrile (CH3CN), which is partly affected by a Fermi resonance50,54 between this mode and the combination band of the CC stretch and the symmetric CH3 bend, as well as a hot band (ν2 + ν8 – ν8),27-31,45,54 has been studied in the neat liquid,42,44,45,49,51,54 under dilute conditions in a large number of solvents,47,48,50,52,54 at air/liquid interfaces,53,58 as well as in solid matrices.55-57 While a theoretical model that can quantitatively predict the frequency shift of the C≡N stretching vibration for any ‘solvent’ condition is still lacking,54 the corresponding frequency-solvent relationship is well understood at a semi-quantitative level. When dissolved in most solvents, the peak position of the C≡N stretching band of acetonitrile is found to red-shift from its gas phase value of 2266.5 cm-1,27-31 except when dissolved in fluorinated alcohols, for which small blue-shifts are observed.48,52,54 Specifically, the solvent acceptor number, as a quantitative measure of Lewis acidity, was found to be a qualitative reporter of the magnitude of the solvent-induced red-shift with a relation that a larger solvent acceptor number corresponds to a smaller red-shift.50,52 This observation is attributed to an increasingly stronger coordination bond between the nitrogen of the nitrile group and a stronger Lewis acid, as stronger coordination was found to increase the C≡N bond strength.64,65 However, it has been shown that Lewis acidity alone is incapable of quantifying all solvent induced frequency shifts.48,52,54 This observation was interpreted as a complex interplay between non-specific and specific interactions between acetonitrile and the solvent.54 Generally, the solvatochromatic shift of the C≡N stretching band, ν, may be expressed as54

| (1) |

Here, ΔνNS and ΔνS refer to the solvent-induced shifts by non-specific and specific interactions, respectively. The non-specific contribution component can be further decomposed into three independent terms: Upon solvation, the centrifugal distortion of the acetonitrile molecule due to free rotation in the gas phase is reduced, resulting in a red-shift of ΔνC = –0.5 cm-1,51,54 whereas the short-range repulsive forces, which arise from collisions of acetonitrile with solvent molecules, were estimated to give rise to a blue-shift of ΔνR = +4.2 cm-1.51 Thus, the observed red-shifts arise mainly from attractive forces, i.e. dispersive and dipole-dipole interactions between the solvent and solute molecules,51,54 namely,

| (2) |

where D and P are the dielectric strength and polarizability of the solvent, respectively. Reimers and Hall54 estimated the relative contributions of the terms in Eq. (1) by setting ΔνC and ΔνR to the aforementioned values and by fitting the non-specific component of Eq. (1), i.e. ΔνNS = ΔνC + ΔνR + ΔνA, to the frequency shifts of C≡N stretching band of acetonitrile obtained in 33 solvents using Aε and Aα as fitting parameters. They found that whereas PAα falls within the range of –8.2 to –15.1 cm-1, making the largest contribution to ΔνA, the PAε term, which was found to be between –1.5 to –6.5 cm-1, also contributes significantly to the observed red-shifts. The difference between this fit and the experimentally observed shift for a given solvent was then taken to be the specific contribution of this solvent to Δν (i.e., ΔνS). Their findings indicate that the specific contribution term can vary greatly from solvent to solvent. For example, the ΔνS was found to be –0.8 cm-1 for benzene, but +6.7 cm-1 for water and +15.4 cm-1 for trifluoroethanol.

The oscillator strength of the C≡N vibrational transition was also found to be strongly dependent on solvent47,48 or coordination partner.33,34,36,37,39 In particular, previous studies have shown that the C≡N band of acetonitrile is significantly smaller in aprotic solvents than in protic solvents,47,48 due to an increased polarization of the nitrile group upon interaction of the nitrogen-lone pair with a Lewis acid. This can be understood by the following simple theoretical line of argument. If the dipole moment of the C≡N group is thought of as arising from two partial atomic charges ±δq, then, upon displacement δr Thus, an increase in the from the equilibrium C≡N bond length re, the dipole is μ = reδq + δrδq.66 magnitude of the partial charges ±δq results in a larger vibrational transition dipole moment, i.e.

| (3) |

where v0 and v1 are the wavefunctions of the vibrational levels involved in the transition.

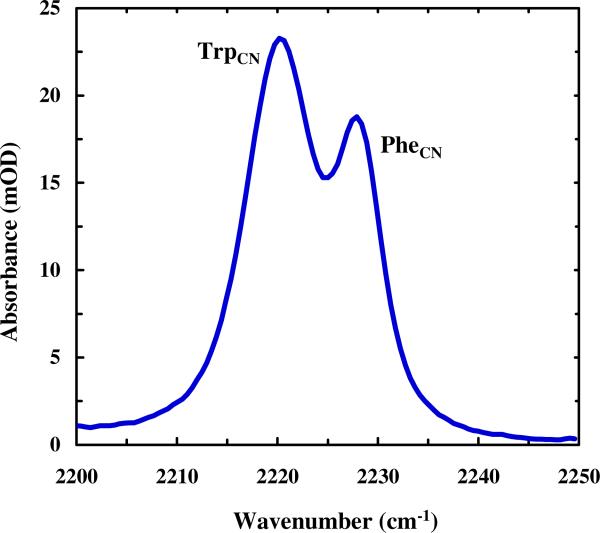

Moreover, it was found that aryl nitriles typically have larger vibrational transition dipole strengths than alkyl nitriles, although the exact value depends on the structure of the aromatic ring (Figure 3).35,36,55,63 For example, whereas the transition dipole of p-tolunitrile was found to be approximately a factor of 1.6 times larger than that of benzonitrile, the oscillator strengths of o-nitrobenzonitrile and m-nitrobenzonitrile were found to be about 6 and 3 times smaller, respectively.36 Similarly, Andrews and Boxer55 found a correlation between the Hammett number and the transition dipole strength of substituted benzonitriles. Cho and co-workers63 found that the extinction coefficient of 4-cyanophenol is smaller than that of 4-cyanophenoxide by a factor of two. These observations can be understood in terms of Eq. (3) as a greater electron donation group to the aromatic ring is expected to result in a larger partial charge on the nitrile moiety.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectrum of the peptide PheCN-Ala-TrpCN in THF at 20 °C, showing that the intensity of the C≡N stretching band of TrpCN is larger than that of PheCN.

Besides alkyl and aryl nitriles, thiocyanates (R-S-C≡N) and cyanates (R-O-C≡N) have also been studied in detail. For example, Londergan and co-workers67 have studied the shape, peak position and extinction coefficient of the nitrile stretching band of methyl thiocyanate in nine solvents. Their results show that the line shape of the C≡N stretching band is symmetric in all solvents studied, except in fluorinated alcohols, which was attributed to the existence of two or more distinct populations of hydrogen-bonded complexes formed between the solvent and solute. Organic cyanates (R-O-C≡N) are also interesting candidates to serve as vibrational probes due to the comparatively large extinction coefficient of the O-C≡N asymmetric stretching mode.68,69 A recent study on phenyl cyanate found that the IR spectrum of this compound exhibits a complex band shape in the O-C≡N stretching region due to the involvement of this vibrational mode in at least two Fermi resonances with overtones,69 rendering derivatives of phenyl cyanate less likely to be useful as vibrational probes in conventional IR studies.

Finally, for experiments in which the chemical dynamics of a system are of interest, the vibrational lifetime of the probe is of great importance as it determines the time window in which the dynamics can be followed. The vibrational lifetimes of a few nitriles have been measured and they typically range from ~1 to 5 ps in water.62,63,70,71

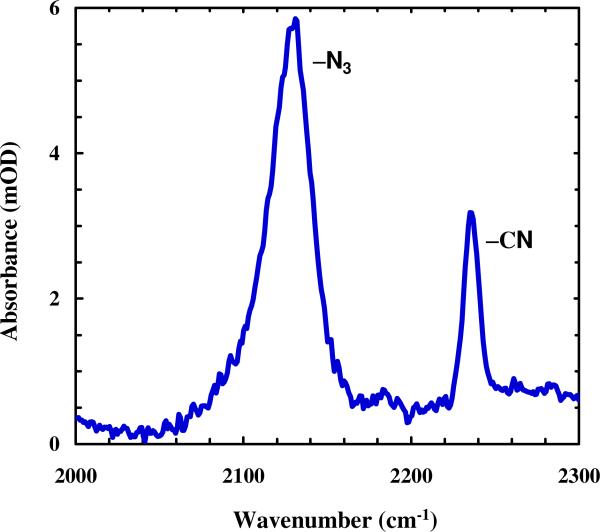

Properties of the asymmetric stretching mode of organic azides (R-N3)

The asymmetric stretching vibration of alkyl and aryl azides (R-N3) are also attractive candidates as vibrational probes of biomolecules as their vibrational transition dipole moments are typically stronger than that of C≡N stretching modes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

FTIR spectrum of the peptide PheCN-Ala-PheN3 in water at 20 °C, showing the relative oscillator strengths of nitrile and azide. The peptide concentration was ~2 mM and the optical pathlength was ~70 μm.

Unfortunately, contrary to the IR spectra of most nitrile compounds, which typically show a single, sharp band (Δν = 6−15 cm-1) in the C≡N stretching region, the band of the N3 asymmetric stretch of organic azides is much broader (Δν = 25−40 cm-1) and typically convolved with one or more bands in the same region. The origin of this complexity has been the topic of various studies.72-75 Early studies tentatively attributed the band structure to mixing between a combination tone of low frequency vibrations and the N3 asymmetric stretch due to anharmonic coupling.72,74 For example, in a systematic study of the vibrational spectra of various aromatic acid azides (R-CON3), Lieber and coworkers72 found that the IR spectra of all aryl acid azides have two peaks in the N3 asymmetric stretching region (around 2200 cm-1), except those whose CON3 group is separated from the aromatic phenyl ring by one or more methylene groups. They interpreted this splitting as the result of a Fermi resonance between a combination band and the N3 asymmetric stretching band. The combination band was thought to arise from the combination of the N3 symmetric stretch (~1200 cm-1) and a band at ~1000 cm-1, which was tentatively attributed to one of the aromatic ring modes. Similarly, the study of Dyall and Kemp74 on a series of aryl azides also suggested that the complex band structure is more likely to arise from a Fermi resonance than from hot bands. In a more recent experiment, Cheatum and coworkers75 found direct evidence of a Fermi resonance interaction between the N3 asymmetric stretch and a combination or overtone state in the form of cross-peaks in the 2D-IR spectrum of 3-azidopyridine at early delay times.

The presence of a Fermi resonance will certainly complicate the interpretation of the experimental results as those vibrations involved in the resonance are expected to be affected differently by the corresponding environmental changes. In several instances, however, Brewer and coworkers have demonstrated that such Fermi resonances can be eliminated by isotope editing of the azide group.76 In addition, in support of the interpretations provided in earlier studies,72 Hochstrasser and coworkers77 found that the IR spectrum of the non-aromatic compound 2'-azido-2'-deoxyuridine in the N3 asymmetric stretch region exhibits a single, sharp peak.

Theoretical modeling of vibrational lineshapes of nitriles, thiocyanates, and azides

In order to facilitate a quantitative, structurally-based interpretation of any experimentally determined vibrational spectra, it is highly desirable to model such spectra via molecular simulations. To this end, many theoretical and computational studies haven been carried out. In particular, for the calculation of nitrile stretching frequencies and vibrational lineshapes, two empirical approaches have gained popularity. The first approach originated in the groups of Cho78-84 and Skinner,85 while the second was recently introduced by Corcelli and coworkers.86-88 Both methods rely on a robust classical molecular mechanical (MM) or quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) simulation of the system of interest. In the first approach,78-85 QM harmonic or anharmonic frequency analyses of the vibrational transition of interest are performed on a large number (tens to thousands) of solute-solvent clusters, which are randomly chosen from the trajectory, resulting in a set of distinct ab initio frequencies to which the following equation is fit:

| (4) |

where φi and Ei,j are the electrostatic potential and Cartesian electric field component j at position i, arising from the solvent environment, and the constants of proportionality α and β are determined by fitting the model to the ab initio determined vibrational frequencies of the probe-solvent clusters, assuming the appropriate gas phase frequency ωgas of the probe. Once the parameters α and β are determined, the fluctuation of the frequency along the molecular dynamics (MM or QM/MM) trajectory may be easily calculated via Eq. (4) by summing over all solvent partial charges. Using a related method, we recently showed that the broadening of the nitrile band of 5-cyanoindole upon hydration is partly due to interactions between water and the aromatic indole ring and does not only arise from direct interactions between water and the nitrile moiety.89

The second approach, developed by Corcelli and coworkers,86-88 is based on the PM3 semi-empirical method, which was optimized to reproduce the C≡N vibrational frequencies of acetonitrile-water clusters. Using the single set of parameters obtained via this optimization procedure, they found quantitative agreement between the experimental and the calculated C≡N vibrational bandwidths of acetonitrile in both water and tetrahydrofuran (THF). Furthermore, they correctly predicted the solvent-induced frequency shift when going from THF to water,87 indicating that the method is “solvent transferable”. As the purpose of using a site-specific spectroscopic reporter is, in many cases, to probe the heterogeneous environment found in biomolecular systems, solvent transferability of a method for lineshape calculation is, therefore, of paramount importance. Though the former method based on Eq. (4) typically provides good agreement between experimental and calculated lineshapes,78-85,89 it is not entirely clear to what extent the resulting frequency-frequency map is solvent transferable. However, some evidence for transferability can be found in the literature.79,90-92

Force field parameters are currently available for a range of model compounds of the aforementioned probes,81,87,89,93-96 but not all of those may be entirely compatible with commonly used force fields in molecular dynamics simulations, as they were derived by procedures that are different from those typically employed for a particular force field. To ensure the integrity of a molecular dynamics simulation of a more complex system containing a specific vibrational probe, it would be beneficial to have parameters available that were derived using the standard procedures for a given force field.

Specific Examples

Taken together, results emerging from previous studies on simple nitrile, thiocyanate, cyanate and azide compounds indicated that the stretching vibration of some diatomic and/or triatomic moieties such as C≡N and N3 are sensitive vibrational probes of their local environment. However, to be applicable in biological studies, such probes need to be first incorporated into the biological molecules of interest. The most common practice is to incorporate these probes into polypeptides or nucleic acid strands in the format of unnatural amino acids or nuclei acids. As summarized in Table 1, a large number of unnatural amino and nucleic acids have been tested as site-specific spectroscopic probes of the local environment and/or conformation of biological systems. Below we highlight a few specific examples, showing how such unnatural vibrational reporters could be used to provide new insight into biological and/or biophysical problems of interest. Unfortunately, the entire body of deserving studies cannot be reviewed in this section and the interested reader may find other very interesting applications of these probes in the references cited.97-113

Probing local electrostatics

Because of the relatively large Stark tuning rate of the nitrile stretching vibration, one of its applications is to measure the local electric field in chemical and biological systems. For example, by incorporating β-AlaSCN into the active site pocket of the enzyme ketosteroid isomerase (KSI) and using the nitrile stretching mode as a vibrational Stark probe, Boxer, Herschlag, and coworkers114 studied the changes in the local electrostatic field associated with substrate binding and steroid isomerization induced charge localization. Based on the estimate that the steroid will displace 8−10 water molecules, they found a surprisingly small change in the electrostatic character of the active site of ~0.6 MV/cm along the C≡N axis upon binding. On the contrary, they found that binding of a transition-state analogue, equilenin, whose negative charge is localized on the carbonyl, lead to a more significant change in the local electrostatic field (~3 MV/cm). In a similar study using β-AlaSCN as an IR electrostatic reporter, Webb and coworkers115 investigated how the local electrostatic field at the interface of the Ras binding domain of the protein Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator (RalGDS) changes upon binding of the protein Rap or Ras. Their results showed that the stretching frequencies of the S-C≡N reporter obtained with eleven RalGDS mutants are weakly correlated with the solvent accessible surface areas (SASAs) of the mutational sites. This observation suggests that the stretching frequency of the S-C≡N group provides a direct, site-specific experimental measure of the SASA. In addition, their results indicated that this IR reporter could be used to identify residues that are responsible for binding. In a more recent study, Webb and coworkers116 employed Stark spectroscopy and p-PheCN as a local electrostatic probe to directly assess the dipole electric field in bicelle model membranes by inserting a p-PheCN-labeled trans-membrane helix into the bilayer. Their results provided an estimate of this electric field, which extends from the intermediate region near the lipid headgroup to the center of the lipid bilayer and is about −6 MV/cm.

As discussed above, the vibrational frequency of a nitrile or azide can be affected by both electric field and hydrogen bonding interactions. Thus, it is imperative to separately determine these two effects when using such vibrational reporters as local electrostatic probes of biological molecules. Recently, Boxer and coworkers117 proposed a method for decomposing the apparent vibrational frequency shifts into hydrogen bonding- and electrostatic field-induced components.

Characterization of amyloid formation and intrinsically disordered proteins

Recently, Raleigh, Zanni, and coworkers118 and the groups of Decatur and Kirschner119 demonstrated that the nitrile stretching vibration is a useful probe of the kinetics and mechanism of amyloid formation. For example, by using p-PheCN as a site-specific IR and fluorescence probe Marek et al.118 were able to characterize the transient species that are populated in the lag-phase of amyloid formation of human islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP). By combining fluorescence and IR measurements on p-PheCN labeled fibrils, they further demonstrated that the aromatic residues are exposed to different extents in the fibrils of IAPP. In a different application, utilizing the S-C≡N reporter, Londergan and coworkers120 mapped the disorder-to-order transition of the intrinsically disordered C-terminal domain of the measles virus nucleoprotein (NTAIL) upon binding to another protein, which triggers structure formation in NTAIL. They demonstrated that the observed vibrational shifts report on both the local gain in secondary structure and on changes in the hydrophobicity of the microenvironment in the vicinity of the probe upon transition from the disordered to the ordered state.

Probing the structure and orientation of membrane-bound peptides

Using a series of p-PheCN-derivatized mutants of a membrane-binding peptide (i.e., mastoparan ×) in conjunction with IR polarization measurements, Tucker et al.121 demonstrated that the nitrile stretching band could be used to report on the location and structure of membrane-bound helical peptides. The successful implementation of this application is based on the notion that in an α-helix the orientations of individual sidechains follow a specific pattern and thus, by measuring the linear dichroic ratio of the C≡N stretching band of representative peptide mutants, it is possible to provide a highly quantitative structural description of the membrane-bound peptide of interest. Similarly, using p-PheCN as an IR environmental reporter Mukherjee et al.122 studied how mastoparan × interacts with another model membrane system, AOT reverse micelles (RMs). Their results indicated that in low water loading RMs mastoparan × forms an α-helix with both the backbone and hydrophobic sidechains mostly dehydrated, and more interestingly, that the α-helix orients itself in such a manner that its hydrophobic face is directed towards the water pool.

Probing light-induced conformational changes in membrane proteins

Using the azido stretching vibration as an IR probe, Ye et al.123 studied the conformational changes of rhodopsin induced by retinal photoisomerization. This process is known to trigger a cascade of protein conformational events from the dark state involving discrete and spectroscopically distinguishable states, including the inactive states Lumi and Meta I, as well as the active state Meta II (for rhodopsin). They found that the azido stretching frequency of p-PheN3, which was incorporated at position 250 on helix 6 (H6), does not show any detectable changes between the dark and Lumi states, but shows a red-shift when the Meta I state is populated. Combined with results obtained with other azido-derivatized versions of the protein, they concluded that H6 in the Meta I is rotated from its original alignment in the dark state, which brings the azido group from a hydrophilic to a hydrophobic environment. This study highlights the usefulness of nitrile and azide based probes in the study and understanding of the structure-dynamics-function relationship of proteins.

Other Spectroscopic Applications

Some of the aforementioned vibrational probes also find interesting applications in other forms of spectroscopy, an added advantage that most probes do not offer. Below we summarize the relevant fluorescence and NMR applications.

Fluorescence and FRET applications

Besides its application as a vibrational probe, p-PheCN can also be used as a fluorescent probe due to its appreciable quantum yield of ~0.11 in water.124,125 Tucker et al.124 found that the fluorescence intensity of p-PheCN is very sensitive to solvent environment and can be selectively excited in the presence of other aromatic amino acids. For example, they found that the fluorescence intensity of p-PheCN is about ten times lower in acetonitrile than in water and hence could be used to determine the binding constant of peptide-protein or protein-protein complexes. Recently, the photophysics of p-PheCN was investigated in more detail by Serrano et al.125 as well as Raleigh and coworkers.126,127 Utilizing p-PheCN fluorescence, Tang et al.128 probed the folding dynamics of the membrane binding peptide anti-αIIb. Following rapid mixing of anti-αIIb with model membranes using stopped-flow, they found three distinct phases in the observed fluorescence signal, which were attributed to the kinetic steps of binding, insertion, and dimerization of the peptide in the membrane. Interestingly, they found that the helix-helix association process occurs on the order of a few seconds, which is substantially slower compared to the folding of the coiled-coil motif in solution as well as orders of magnitudes slower than that expected for a diffusion limited reaction, suggesting that the helix-helix association rate is determined by the actual process itself, which requires proper backbone orientations and well-defined intermolecular side chain-side chain interactions.

Moreover, Tucker et al.129 demonstrated that p-PheCN can be used as a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) donor to tryptophan (Trp). With a Förster radius of approximately 16.0 Å, this FRET pair is ideally suited to probe distances within small proteins and peptides and has been used to probe the conformational distribution of unstructured peptides as well as protein unfolding.130,131 More recently, Rogers et al.131 expanded the FRET application of p-PheCN by including FRET acceptors consisting of other unnatural aromatic amino acids, such as 5-hydroxytryptophan and 7-azatryptophan, showing the possibility of performing more sophisticated (e.g., three-step) FRET measurements using unnatural amino acid FRET pairs. The studies of Taskent-Sezgin et al. and Waegele et al. indicated that tyrosine126 and 5-TrpCN132 are also effective quenchers of the fluorescence of p-PheCN, further expanding the potential applications of this versatile spectroscopic probe.

NMR applications

The chemical shift of the carbon atom (13C) in nitriles is located in an uncongested region of the NMR spectrum of proteins and is sensitive to its environment.133 Similarly, the chemical shift of the nitrile nitrogen (15N) is found to be sensitive to solvent,47,48 with the relation that the chemical shift decreases with increasing solvent acceptor number. In addition, Brewer and coworkers134 have recently shown, using 15N-labeled 2'-azido-2'-deoxyuridine as an example, that the chemical shift of azide is also sensitive to its environment. Taken together, these previous studies indicate that both nitrile and azide groups could serve as site-specific NMR probes of the local environment of biomolecules. For example, Waldman et al.12 and Doherty et al.13 have both used 13C cyanylated cysteines to qualitatively examine how ligand binding affects the environment of protein binding sites, while Boxer and workers117 have used nitrile NMR chemical shifts to facilitate a quantitative assessment of changes in the electrostatic field of the binding pocket of ketosteroid isomerase upon ligand association.

Potential Structural and Energetic Perturbations

Despite their small sizes, incorporation of nitrile, thiocyanate, or azide probes into proteins will lead to unavoidable perturbations of the native properties of the system of interest, such as the structure, stability and enzymatic activity. To address this concern, several studies have been carried out to characterize the degree of structural and energetic perturbations of various nitrile and/or azide probes in detail.127,135-137 For example, Raleigh and coworkers127 investigated how azidohomoalanine affects the folding stability of the protein NTL9 and found that its destabilizing effect (20−40%) is dependent on the position of the probe. Similarly, Romesberg and coworkers137 investigated the energetic and structural perturbations of p-PheCN on cytochrome c, while Boxer and coworkers136 showed that incorporation of β-AlaSCN into RNase results in only small decreases in both Km and kcat, as well as minor perturbations to the global and local structures of the protein as judged by crystallographic data. Taken together, these previous studies indicate that incorporation of a nitrile or azide probe into proteins, when in the form of an unnatural amino acid, causes context dependent structural and energetic perturbations that could be minimized.

Summary and Outlook

Nitriles, thiocyanates and azides represent powerful spectroscopic probes for the investigation of structure and dynamics of a range of biological and biochemical systems. Each of the presented probes has intrinsic advantages and disadvantages and the best choice for a specific probe depends on the particular system of interest and application. In addition, previous works have mostly focused on testing the applicability of these probes, rather than elucidating specific questions. Therefore, we expect an increase in application of these probes to a wide range of biological and biophysical questions. Below we offer some potential future areas of interest in this rapidly expanding field.

Using two unnatural IR probes to infer distance

The study of Zanni and coworkers102 suggested that coupling between vibrational dipoles of two nearby nitriles might be used to probe short distances in biomolecules. However, further nonlinear experiments that can directly probe vibrational couplings138 of nitriles are required to substantiate the utility of this method. Recently, using model compounds, Rubtsov and coworkers61 have shown that vibrational energy transfer via through-bond relaxation could be used to infer distances between vibrators whose separation is beyond the length scale for which appreciable direct anharmonic coupling occurs. Thus, another direction worth exploring is to determine the feasibility of this technique for protein conformational studies using, for example, peptide systems that contain either two nitriles (Figure 3) or one nitrile and one azide group (Figures 4).

Probing local dynamics and dynamic heterogeneity of proteins

Several recent time-resolved studies137,139-141 have shown that nitrile and azide probes are extremely useful in revealing the heterogeneity of local protein dynamics or the dynamics of interfacial water molecules. Thus, it is expected that application of these probes in conjunction with various linear and nonlinear IR methods will continue to provide new insights into the relation between structure, dynamics and function of proteins. In this context, however, new challenges arise. Obtaining reliable spectroscopic signals from some of the probes presented here in photon echo experiments and also time-resolved linear vibrational spectroscopies has proven to be difficult owing to their comparatively low extinction coefficients. Utilization of azide reporters with larger extinction coefficients should mitigate this problem (Table 1). However, a larger extinction coefficient comes at the expense of a larger dipole moment (Eq. 3), which in turn may give rise to a larger perturbation of the system. Thus, a trade-off exists between signal strength and energetic and structural perturbation. We anticipate that these considerations will become increasingly more important as the field is moving towards the investigation of more complex systems.

Developing new probes and applications

While the aforementioned probes are useful in many applications, they cannot possibly meet all needs. Thus, we expect that the pool of site-specific spectroscopic probes142 will continue to expand. For example, it would be very beneficial to develop a site-specific IR reporter of protein backbones. Among the potential strategies, amide to ester backbone mutations143 are especially worth pursuing because the CO stretching vibration of esters has a large molar absorption coefficient and is centered in the range of 1700–1800 cm-1 where other functional groups do not absorb. Another interesting direction we believe is worth exploring is to quantitatively examine the factors that control the signature of the Fermi resonance of aryl azides. While in many spectroscopic applications Fermi resonances often pose a nuisance, their signatures could be a very useful probe of protein structure and environment. Furthermore, Spiro and coworkers144 have shown that p-PheCN also exhibits strong Raman scattering, suggesting that the vibrational probes discussed above are expected to find important Raman applications, especially in cases where IR measurements are not feasible (e.g., in solids or strongly scattering samples and surfaces).

Developing new computational and theoretical methods

We can also expect that continued effort will be made to refine existing computational methods and/or develop more advanced methods for easy and accurate calculation of the vibrational property of the probe of interest, which would facilitate a more detailed interpretation of experiments.92 Further exploration of the mechanistic origins64,65,145 of vibrational frequency shifts will also be helpful in both refining computational methods and interpreting experimental results.

QUOTES

One of the advantages of using unnatural amino acid spectroscopic probes is that they often induce minimal perturbation to the protein structure in question and can be incorporated into the polypeptide sequence of interest using either in vitro or in vivo methods.

Nitriles, thiocyanates and azides represent powerful spectroscopic probes for the investigation of structure and dynamics of a range of biological and biochemical systems. Each of the presented probes has intrinsic advantages and disadvantages and the best choice for a specific probe depends on the particular system of interest and application.

In addition, previous works have mostly focused on testing the applicability of these probes, rather than elucidating specific questions. Therefore, we expect an increase in application of these probes to a wide range of biological and biophysical questions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM-065978, RR01348 and GM-008275) for funding. R.M.C. is a Structural Biology Training Grant Fellow.

Biography

Matthias M. Waegele obtained his Ph.D. degree in Physical Chemistry from the University of Pennsylvania in 2011. He is currently a postdoctoral fellow at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, where he investigates the mechanism of the water oxidation reaction on photo-driven transition metal oxide catalyst surfaces.

Robert M. Culik is a Ph.D. candidate in the graduate group of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics at the University of Pennsylvania. He graduated with a B.S. in Molecular Biology from the University of Pittsburgh in 2008. His research interests include developing new methods for studying complex folding dynamics.

Feng Gai is a Professor of Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania. His current research interests focus on protein folding, structure-dynamic-function relationship, as well as the development of new spectroscopic probes and methods. http://gailab4.chem.upenn.edu/

REFERENCES

- 1.Tadesse L, Nazarbaghi R, Walters L. Isotopically Enhanced Infrared-Spectroscopy – A Novel Method for Examining Secondary Structure at Specific Sites in Conformationally Heterogeneous Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7036–7037. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decatur SM, Antonic J. Isotope-Edited Infrared Spectroscopy of Helical Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11914–11915. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang CY, Getahun Z, Wang T, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Time-Resolved Infrared Study of the Helix-Coil Transition Using C-13-Labeled Helical Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12111–12112. doi: 10.1021/ja016631q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decatur SM. Elucidation of Residue-Level Structure and Dynamics of Polypeptides via Isotope-Edited Infrared Spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:169–175. doi: 10.1021/ar050135f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thielges MC, Case DA, Romesberg FE. Carbon-Deuterium Bonds as Probes of Dihydrofolate Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6597–6603. doi: 10.1021/ja0779607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller CS, Ploetz EA, Cremeens ME, Corcelli SA. Carbon-Deuterium Vibrational Probes of Peptide Conformation: Alanine Dipeptide and Glycine Dipeptide. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:125103. doi: 10.1063/1.3100185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann J, Thielges MC, Yu W, Dawson PE, Romesberg FE. Carbon-Deuterium Bonds as Site-Specific and Nonperturbative Probes for Time-Resolved Studies of Protein Dynamics and Folding. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:412–416. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendel D, Cornish VW, Schultz PG. Site-Directed Mutagenesis with an Expanded Genetic Code. Annu. Rev. of Biophys. Biom. 1995;24:435–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor RE, Tirrell DA. Non-Canonical Amino Acids in Protein Polymer Design. Polym. Rev. 2007;47:9–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayers B, Blaschke UK, Camarero JA, Cotton GJ, Holford M, Muir TW. Introduction of Unnatural Amino Acids into Proteins Using Expressed Protein Ligation. Biopolymers. 1999;51:343–354. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1999)51:5<343::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotton GJ, Muir TW. Generation of a Dual-labeled Fluorescence Biosensor for Crk-II Phosphorylation using Solid-phase Expressed Protein Ligation. Chem. Biol. 2000;7:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waldman ADB, Birdsall B, Roberts GCK, Holbrook JJ. 13C NMR and Transient Kinetic Studies on Lactate Dehydrogenase [Cys(13CN)165]. Direct Measurement of a Rate-Limiting Rearrangement in Protein Structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1986;870:102–111. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doherty GM, Motherway R, Mayhew SG, Malthouse JPG. 13C NMR of Cyanylated Flavodoxin from Megasphaera Elsdenii and of Thiocyanate Model Compounds. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7922–7930. doi: 10.1021/bi00149a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fafarman AT, Webb LJ, Chuang JI, Boxer SG. Site-Specific Conversion of Cysteine Thiols into Thiocyanate Creates an IR Probe for Electric Fields in Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13356–13357. doi: 10.1021/ja0650403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jo H, Culik RM, Korendovych IV, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Selective Incorporation of Nitrile-Based Infrared Probes into Proteins via Cysteine Alkylation. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10354–10356. doi: 10.1021/bi101711a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baburaj K, Azam N, Udgaonkar D, Durani S. HOCGO and DMACGO – 2 Coumarin Derived Alpha-Dicarbonyls Suitable as pH and Polarity Sensitive Fluorescent Reporters for Proteins that can be Targeted at Reactive Arginines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1199:253–265. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuda T, Kaya S, Funatsu H, Hayashi Y, Taniguchi K. Fluorescein 5’-Isothiocyanate-Modified Na+,K+-ATPase, at Lys-501 of the α-Chain, Accepts ATP Independent of Pyridoxal 5’-Diphospho-5’-Adenosine Modification at Lys-480. J. Biochem. 1998;123:169–174. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson MA, Colman RF. Resonance Energy Transfer between the Adenosine 5’-Diphosphate Site of Glutamate Dehydrogenase and a Guanosine 5’-Triphosphate Site Containing a Tyrosine Labeled with 5’-[p-(Fluorosulfonyl)benzoyl]-1,N6-ethenoadenosine. Biochemistry. 1983;22:4247–4257. doi: 10.1021/bi00287a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heim R, Prasher DC, Tsien RY. Wavelength mutations and posttranslational autooxidation of green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:12501–12504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furter R. Expansion of the genetic code: Site-directed p-fluoro-phenylalanine incorporation in E. coli. Prot. Sci. 1998;7:419–426. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Brock A, Herberich B, Schultz PG. Expanding the genetic code of E. coli. Science. 2001;292:498–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1060077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowie DB, Cohen GN. Biosynthesis by E. coli of Active Altered Proteins Containing Selenium instead of Sulfur. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1957;26:252–261. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brawerman G, Ycas M. Incorporation of the Amino Acid Analog Tryptazan into the Proteins of E. coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1957;68:112–117. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(57)90331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munier R, Cohen GN. Incorporation of Structural Analogues of Amino Acid into the Bacterial Proteins during their Synthesis in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1959;31:378–391. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owrutsky JC, Raftery D, Hochstrasser RM. Vibrational Relaxation Dynamics in Solutions. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1994;45:519–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pc.45.100194.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Getahun Z, Huang CY, Wang T, DeLeon B, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Using Nitrile-Derivatized Amino Acids as Infrared Probes of Local Environment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:405–411. doi: 10.1021/ja0285262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkateswarlu P. The Rotation-Vibration Spectrum of Methyl Cyanide in the Region 1.6μ-20μ. J. Chem. Phys. 1951;19:293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson HW, Williams RL. The Infra-Red Spectra of Methyl Cyanide and Methyl Isocyanide. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1952;48:502–513. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker FW, Nielsen AH, Fletcher WH. The Infrared Absorption Spectrum of Methyl Cyanide Vapor. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1957;1:107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakagawa I, Shimanouchi T. Rotation-Vibration Spectra and Rotational, Coriolis Coupling, Centrifugal Distortion and Potential Constants of Methyl Cyanide. Spectrochim. Acta. 1962;18:513–539. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki I, Nakagawa J, Fujiyama T. Vibration-rotation Spectrum of Methyl Cyanide - Analyses of ν2 and ν3 + ν4 Bands. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A. 1977;33:689–698. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiederkehr RR, Drickamer HG. Effect of Pressure on Cyanide and Carbonyl Spectra in Solution. J. Chem. Phys. 1958;28:311–316. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coerver HJ, Curran C. Infrared Absorption by the C≡N Bond in Addition Compounds of Nitriles with Some Inorganic Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958;80:3522–3523. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerrard W, Lappert MF, Pyszora H, Wallis JW. Infrared Spectra of Nitriles and their Complexes with Boron Trichloride. J. Chem. Soc. 1960:2182–2186. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown TL. A Molecular Orbital Model for Infrared Band Intensities: Functional Group Intensities in Aromatic Compounds. J. Phys. Chem. 1960;64:1798–1804. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown TL, Kubota M. Molecular Addition Compounds of Tin(IV) Chloride. 2. Frequency and Intensity of Infrared Nitrile Absorption in Benzonitrile Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961;83:4175–4177. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Augdahl E, Klaboe P. Spectrocopic Studies of Charge Transfer Complexes. 6. Nitriles and Iodine Monochloride. Spectrochim. Acta. 1963;19:1665–1673. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans JC, Lo GYS. Raman and Infrared Studies of Acetonitrile Complexed with Zinc Chloride. Spectrochim. Acta. 1965;21:1033–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brewer DG, Wong PTT. Studies of Metal Complexes of Pyridine Derivatives. Effects of Coordination upon Infrared Intensity of Functional Group in β-Cyanopyridine. Can. J. Chem. 1966;44:1407–1419. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawai K, Kanesaka I. Infrared Spectra of Addition Compounds of Hydrogen and Deuterium Cyanides with Some Inorganic Chlorides. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A. 1969;25:1265–1273. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas BH, Orvillet WJ. Molecular Parameters and Bond Structure. 8. Environmental Effects on ν(C≡N) Bond Stretching Frequencies. J. Mol. Struct. 1969;3:191–206. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothschild WG. Molecular Motion in Liquids: Rotational and Vibrational Relaxation in Highly Polar and Strongly Associated Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1972;57:991–12. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breuillard-Alliot C, Soussen-Jacob J. Etude des mouvements moleculaires en milieu liquide a partir du profil des bandes de vibration dans l'infrarouge et des fonctions de correlation. Mol. Phys. 1974;28:905–920. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loewenschuss A, Yellin N. Secondary Structure of Some Acetonitrile Vibrational Bands. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A. 1975;31:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fini G, Mirone P. Secondary Structure of Some Vibrational Bands of Acetonitrile. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A. 1976;32:439–440. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawano Y, Hase Y, Sala O. Vibrational-Spectra of Adducts of Acetonitrile with Titanium and Tin Tetrachloride. J. Mol. Struct. 1976;30:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eaton G, Penanunez AS, Symons MCR, Ferrario M, McDonald IR. Spectroscopic and Molecular-Dynamics Studies of Solvation of Cyanomethane and Cyanide Ions. Faraday Discuss. 1988;85:237–253. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eaton G, Penanunez a. S., Symons MCR. Solvation of Cyanoalkanes [CH3CN] and [(CH3)3CCN] - an Infrared and Nuclear Magnetic-Resonance Study. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. I. 1988;84:2181–2193. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashimoto S, Ohba T, Ikawa S-I. Infrared and Molecular Dynamics Study of Reorientational Relaxation of Liquid Acetonitrile. Chem. Phys. 1989;138:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nyquist RA. Solvent-Induced Nitrile Frequency-Shifts - Acetonitrile and Benzonitrile. Appl. Spectrosc. 1990;44:1405–1407. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benamotz D, Lee MR, Cho SY, List DJ. Solvent and Pressure-Induced Perturbations of the Vibrational Potential Surface of Acetonitrile. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;96:8781–8792. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fawcett WR, Liu GJ, Kessler TE. Solvent-Induced Frequency-Shifts in the Infrared-Spectrum of Acetonitrile in Organic-Solvents. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:9293–9298. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang H, Borguet E, Yan ECY, Zhang D, Gutow J, Eisenthal KB. Molecules at Liquid and Solid Surfaces. Langmuir. 1998;14:1472–1477. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reimers JR, Hall LE. The Solvation of Acetonitrile. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:3730–3744. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andrews SS, Boxer SG. Vibrational Stark Effects of Nitriles I. Methods and Experimental Results. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2000;104:11853–11863. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andrews SS, Boxer SG. Vibrational Stark Effects of Nitriles II. Physical Origins of Stark Effects from Experiment and Perturbation Models. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:469–477. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suydam IT, Boxer SG. Vibrational Stark Effects Calibrate the Sensitivity of Vibrational Probes for Electric Fields in Proteins. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12050–12055. doi: 10.1021/bi0352926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao Y, Comstock M, Eisenthal KB. Absolute Orientation of Molecules at Interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:1727–1732. doi: 10.1021/jp055340r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aschaffenburg DJ, Moog RS. Probing Hydrogen Bonding Environments: Solvatochromic Effects on the CN Vibration of Benzonitrile. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:12736–12743. doi: 10.1021/jp905802a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim YS, Hochstrasser RM. Chemical Exchange 2D IR of Hydrogen-Bond Making and Breaking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:11185–11190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504865102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kurochkin DV, Naraharisetty SRG, Rubtsov IV. A Relaxation-Assisted 2D IR Spectroscopy Method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:14209–14214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700560104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghosh A, Remorino A, Tucker MJ, Hochstrasser RM. 2D IR Photon Echo Spectroscopy Reveals Hydrogen Bond Dynamics of Aromatic Nitriles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009;469:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2008.12.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ha J-H, Lee K-K, Park K-H, Choi J-H, Jeon S-J, Cho M. Integrated and Dispersed Photon Echo Studies of Nitrile Stretching Vibration of 4-Cyanophenol in Methanol. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:204509–9. doi: 10.1063/1.3140402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Purcell KF, Drago RS. Studies of Bonding in Acetonitrile Adducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966;88:919–924. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beattie IR, Gilson T. Normal Co-ordinate Analysis of MeCNBX3 and its Relevance to Thermodynamic Stability of Co-ordination Compounds. J. Chem. Soc. 1964:2292–2295. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Atkins P, de Paula J. Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maienschein-Cline MG, Londergan CH. The CN Stretching Band of Aliphatic Thiocyanate is Sensitive to Solvent Dynamics and Specific Solvation. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2007;111:10020–10025. doi: 10.1021/jp0761158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Groving N, Holm A. Alkyl Cyanates. 4. Infrared and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra. Acta Chem. Scand. 1965;19:443–450. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tucker MJ, Kim YS, Hochstrasser RM. 2D IR Photon Echo Study of the Anharmonic Coupling in the OCN Region of Phenyl Cyanate. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009;470:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurochkin DV, Naraharisetty SRG, Rubtsov IV. Dual-Frequency 2D IR on Interaction of Weak and Strong IR Modes. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2005;109:10799–10802. doi: 10.1021/jp055811+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fang C, Bauman JD, Das K, Remorino A, Arnold E, Hochstrasser RM. Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectra Reveal Relaxation of the Nonnucleoside Inhibitor TMC278 Complexed with HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:1472–1477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709320104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lieber E, Rao CNR, Thomas AE, Oftedahl E, Minnis R, Nambury CVN. Infrared Spectra of Acides, Carbamyl Azides and Other Azido Derivatives - Anomalous Splittings of the N3 Stretching Bands. Spectrochim. Acta. 1963;19:1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sheinker YN, Senyavin LB, Zheltova VN. Position and Intensity of Absorption Band Due to Antisymmetric Valence Vibration of N3 Group in Infra-Red Spectra of Organic Azides. Dokl. Akad. Nauk. 1965;160:1339. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dyall LK, Kemp JE. Infrared Spectra of Aryl Azides. Aust. J. Chem. 1967;20:1395–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nydegger MW, Dutta S, Cheatum CM. Two-Dimensional Infrared Study of 3-Azidopyridine as a Potential Spectroscopic Reporter of Protonation State. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;133:134506–8. doi: 10.1063/1.3483688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lipkin JS, Song R, Fenlon EE, Brewer SH. Modulating Accidental Fermi Resonance: What a Difference a Neutron Makes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:1672–1676. doi: 10.1021/jz2006447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tucker MJ, Gai XS, Fenlon EE, Brewer SH, Hochstrasser RM. 2D IR photon echo of azido-probes for biomolecular dynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:2237–2241. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01625j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ham S, Kim JH, Lee H, Cho MH. Correlation between Electronic and Molecular Structure Distortions and Vibrational Properties. II. Amide I Modes of NMA-nD2O Complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:3491–3498. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kwac K, Lee H, Cho MH. Non-Gaussian Statistics of Amide I Mode Frequency Fluctuation of N-Methylacetamide in Methanol Solution: Linear and Nonlinear Vibrational Spectra. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:1477–1490. doi: 10.1063/1.1633549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Choi JH, Oh KI, Cho MH. Azido-Derivatized Compounds as IR Probes of Local Electrostatic Environment: Theoretical Studies. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:174512. doi: 10.1063/1.3001915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oh K-I, Choi J-H, Lee J-H, Han J-B, Lee H, Cho M. Nitrile and Thiocyanate IR Probes: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:154504–10. doi: 10.1063/1.2904558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Choi J-H, Oh K-I, Lee H, Lee C, Cho M. Nitrile and Thiocyanate IR Probes: Quantum Chemistry Calculation Studies and Multivariate Least-Square Fitting Analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:134506–8. doi: 10.1063/1.2844787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cho M. Vibrational Solvatochromism and Electrochromism: Coarse-Grained Models and Their Relationships. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:094505–15. doi: 10.1063/1.3079609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee H, Choi J-H, Cho M. Vibrational Solvatochromism and Electrochromism of Cyanide, Thiocyanate, and Azide Anions in Water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010;12:12658–12669. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00214c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Corcelli SA, Lawrence CP, Skinner JL. Combined Electronic Structure/Molecular Dynamics Approach for Ultrafast Infrared Spectroscopy of Dilute HOD in Liquid H2O and D2O. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:8107–8117. doi: 10.1063/1.1683072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lindquist BA, Corcelli SA. Nitrile Groups as Vibrational Probes: Calculations of the C≡N Infrared Absorption Line Shape of Acetonitrile in Water and Tetrahydrofuran. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:6301–6303. doi: 10.1021/jp802039e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lindquist BA, Haws RT, Corcelli SA. Optimized Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics Strategies for Nitrile Vibrational Probes: Acetonitrile and para-Tolunitrile in Water and Tetrahydrofuran. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:13991–14001. doi: 10.1021/jp804900u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lindquist BA, Furse KE, Corcelli SA. Nitrile Groups as Vibrational Probes of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics: An Overview. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:8119–32. doi: 10.1039/b908588b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Waegele MM, Gai F. Computational Modeling of the Nitrile Stretching Vibration of 5-Cyanoindole in Water. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:781–786. doi: 10.1021/jz900429z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.DeCamp MF, DeFlores L, McCracken JM, Tokmakoff A, Kwac K, Cho M. Amide I Vibrational Dynamics of N-Methylacetamide in Polar Solvents: The Role of Electrostatic Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:11016–11026. doi: 10.1021/jp050257p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jansen TL, Knoester J. A Transferable Electrostatic Map for Solvation Effects on Amide I Vibrations and its Application to Linear and Two-Dimensional Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:044502. doi: 10.1063/1.2148409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Choi J-H, Raleigh D, Cho M. Azido Homoalanine is a Useful Infrared Probe for Monitoring Local Electrostatistics and Side-Chain Solvation in Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:2158–2162. doi: 10.1021/jz200980g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bohm HJ, McDonald IR, Madden PA. An Effective Pair Potential for Liquid Acetonitrile. Mol. Phys. 1983;49:347–360. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yin D. PhD Thesis. University of Maryland; Baltimore, MD: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grabuleda X, Jaime C, Kollman PA. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies of Liquid Acetonitrile: New Six-Site Model. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:901–908. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gee PJ, van Gunsteren WF. Acetonitrile Revisited: A Molecular Dynamics Study of the Liquid Phase. Mol. Phys. 2006;104:477–483. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Callahan BP, Bell AF, Tonge PJ, Wolfenden R. A Raman-active Competitive Inhibitor of OMP Decarboxylase. Bioorg. Chem. 2006;34:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Suydam IT, Snow CD, Pande VS, Boxer SG. Electric Fields at the Active Site of an Enzyme: Direct Comparison of Experiment with Theory. Science. 2006;313:200–204. doi: 10.1126/science.1127159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Aprilakis KN, Taskent H, Raleigh DP. Use of the Novel Fluorescent Amino Acid p-Cyanophenylalanine Offers a Direct Probe of Hydrophobic Core Formation during the Folding of the N-terminal Domain of the Ribosomal Protein L9 and Provides Evidence for Two-state Folding. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12308–12313. doi: 10.1021/bi7010674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kuo CH, Hochstrasser RM. Two Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy and Relaxation of Aqueous Cyanide. Chem. Phys. 2007;341:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kuo CH, Vorobyev DY, Chen JX, Hochstrasser RM. Correlation of the Vibrations of the Aqueous Azide ion with the O-H Modes of Bound Water Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:14028–14033. doi: 10.1021/jp076503+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Krummel AT, Zanni MT. Evidence for Coupling between Nitrile Groups using DNA Templates: A Promising new Method for Monitoring Structures with Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:1336–1338. doi: 10.1021/jp711558a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Naraharisetty SRG, Kasyanenko VM, Rubtsov IV. Bond Connectivity Measured via Relaxation-assisted Two-dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:104502–104508. doi: 10.1063/1.2842071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Niaura G, Kuprionis Z, Ignatjev I, Kazemekaite M, Valincius G, Talaikyte Z, Razumas V, Svendsen A. Probing of Lipase Activity at Air/Water Interface by Sum-frequency Generation Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:4094–4101. doi: 10.1021/jp075950m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Marek P, Gupta R, Raleigh DP. The Fluorescent Amino Acid p-Cyanophenylalanine Provides an Intrinsic Probe of Amyloid Formation. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:1372–1374. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Watson MD, Gai XS, Gillies AT, Brewer SH, Fenlon EE. A Vibrational Probe for Local Nucleic Acid Environments: 5-Cyano-2 '-deoxyuridine. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:13188–13192. doi: 10.1021/jp8067238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu J, Strzalka J, Tronin A, Johansson JS, Blasie JK. Mechanism of Interaction between the General Anesthetic Halothane and a Model Ion Channel Protein, II: Fluorescence and Vibrational Spectroscopy Using a Cyanophenylalanine Probe. Biophys. J. 2009;96:4176–4187. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Miyake-Stoner SJ, Miller AM, Hammill JT, Peeler JC, Hess KR, Mehl RA, Brewer SH. Probing Protein Folding Using Site-Specifically Encoded Unnatural Amino Acids as FRET Donors with Tryptophan. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5953–5962. doi: 10.1021/bi900426d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Taskent-Sezgin H, Chung J, Patsalo V, Miyake-Stoner SJ, Miller AM, Brewer SH, Mehl RA, Green DF, Raleigh DP, Carrico I. Interpretation of p-Cyanophenylalanine Fluorescence in Proteins in Terms of Solvent Exposure and Contribution of Side-Chain Quenchers: A Combined Fluorescence, IR and Molecular Dynamics Study. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9040–9046. doi: 10.1021/bi900938z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee KK, Park KH, Choi JH, Ha JH, Jeon SJ, Cho M. Ultrafast Vibrational Spectroscopy of Cyanophenols. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010;114:2757–2767. doi: 10.1021/jp908696k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gillies AT, Gai XS, Buckwalter BL, Fenlon EE, Brewer SH. (15)N NMR Studies of a Nitrile-Modified Nucleoside. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:17136–17141. doi: 10.1021/jp106493t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gai XS, Coutifaris BA, Brewer SH, Fenlon EE. A direct comparison of azide and nitrile vibrational probes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:5926–5930. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02774j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Smith EE, Linderman BY, Luskin AC, Brewer SH. Probing Local Environments with the Infrared Probe: L-4-Nitrophenylalanine. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:2380–2385. doi: 10.1021/jp109288j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sigala PA, Fafarman AT, Bogard PE, Boxer SG, Herschlag D. Do Ligand Binding and Solvent Exclusion Alter the Electrostatic Character within the Oxyanion Hole of an Enzymatic Active Site?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12104–12105. doi: 10.1021/ja075605a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stafford AJ, Ensign DL, Webb LJ. Vibrational Stark Effect Spectroscopy at the Interface of Ras and Rap1A Bound to the Ras Binding Domain of RalGDS Reveals an Electrostatic Mechanism for Protein-Protein Interaction. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:15331–15344. doi: 10.1021/jp106974e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hu W, Webb LJ. Direct Measurement of the Membrane Dipole Field in Bicelles Using Vibrational Stark Effect Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:1925–1930. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fafarman AT, Sigala PA, Herschlag D, Boxer SG. Decomposition of Vibrational Shifts of Nitriles into Electrostatic and Hydrogen-Bonding Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12811–12813. doi: 10.1021/ja104573b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Marek P, Mukherjee S, Zanni MT, Raleigh DP. Residue-Specific, Real-Time Characterization of Lag-Phase Species and Fibril Growth During Amyloid Formation: A Combined Fluorescence and IR Study of p-Cyanophenylalanine Analogs of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;400:878–888. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Inouye H, Gleason KA, Zhang D, Decatur SM, Kirschner DA. Differential Effects of Phe19 and Phe20 on Fibril Formation by Amyloidogenic Peptide Aβ16-22 (Ac-KLVFFAE-NH2). Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2010;78:2306–2321. doi: 10.1002/prot.22743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bischak CG, Longhi S, Snead DM, Costanzo S, Terrer E, Londergan CH. Probing Structural Transitions in the Intrinsically Disordered C-Terminal Domain of the Measles Virus Nucleoprotein by Vibrational Spectroscopy of Cyanylated Cysteines. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1676–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tucker MJ, Getahun Z, Nanda V, DeGrado WF, Gai F. A New Method for Determining the Local Environment and Orientation of Individual Side Chains of Membrane-Binding Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5078–5079. doi: 10.1021/ja032015d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mukherjee S, Chowdhury P, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Site-Specific Hydration Status of an Amphipathic Peptide in AOT Reverse Micelles. Langmuir. 2007;23:11174–11179. doi: 10.1021/la701686g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ye S, Zaitseva E, Caltabiano G, Schertler GFX, Sakmar TP, Deupi X, Vogel R. Tracking G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Activation Using Genetically Encoded Infrared Probes. Nature. 2010;464:1386–1389. doi: 10.1038/nature08948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tucker MJ, Oyola R, Gai F. A Novel Fluorescent Probe for Protein Binding and Folding Studies: p-Cyano-Phenylalanine. Biopolymers. 2006;83:571–576. doi: 10.1002/bip.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Serrano AL, Troxler T, Tucker MJ, Gai F. Photophysics of a Fluorescent Non-Natural Amino Acid: p-Cyanophenylalanine. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010;487:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Taskent-Sezgin H, Marek P, Thomas R, Goldberg D, Chung J, Carrico I, Raleigh DP. Modulation of p-Cyanophenylalanine Fluorescence by Amino Acid Side Chains and Rational Design of Fluorescence Probes of Alpha-Helix Formation. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6290–6295. doi: 10.1021/bi100932p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Taskent-Sezgin H, Chung J, Banerjee PS, Nagarajan S, Dyer RB, Carrico I, Raleigh DP. Azidohomoalanine: A Conformationally Sensitive IR Probe of Protein Folding, Protein Structure, and Electrostatics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:7473–7475. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tang J, Yin H, Qiu J, Tucker MJ, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Using Two Fluorescent Probes to Dissect the Binding, Insertion, and Dimerization Kinetics of a Model Membrane Peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3816–3817. doi: 10.1021/ja809007f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tucker MJ, Oyola R, Gai F. Conformational Distribution of a 14-Residue Peptide in Solution: A Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:4788–4795. doi: 10.1021/jp044347q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Glasscock JM, Zhu Y, Chowdhury P, Tang J, Gai F. Using an Amino Acid Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Pair to Probe Protein Unfolding: Application to the Villin Headpiece Subdomain and the LysM Domain. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11070–11076. doi: 10.1021/bi8012406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rogers JMG, Lippert LG, Gai F. Non-Natural Amino Acid Fluorophores for One- and Two-Step Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Applications. Anal. Biochem. 2010;399:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Waegele MM, Tucker MJ, Gai F. 5-Cyanotryptophan as an Infrared Probe of Local Hydration Status of Proteins. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009;478:249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Barfield M, Kao LF, Hall HK, Snow LG. Nitrile Function as a Probe of cis/trans Stereochemistry - 13C NMR-Studies of Poly(Bicyclobutane-1-Carbonitrile) and Related Model Compounds. Macromol. 1984;17:240–248. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gai XS, Fenlon EE, Brewer SH. A Sensitive Multispectroscopic Probe for Nucleic Acids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7958–7966. doi: 10.1021/jp101367s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Dutta S, Cook RJ, Houtman JCD, Kohen A, Cheatum CM. Characterization of Azido-NAD+ to Assess Its Potential as a Two-Dimensional Infrared Probe of Enzyme Dynamics. Anal. Biochem. 2010;407:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Fafarman AT, Boxer SG. Nitrile Bonds as Infrared Probes of Electrostatics in Ribonuclease S. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:13536–13544. doi: 10.1021/jp106406p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zimmermann J, Thielges MC, Seo YJ, Dawson PE, Romesberg FE. Cyano Groups as Probes of Protein Microenvironments and Dynamics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:8333–8337. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kim YS, Hochstrasser RM. Applications of 2D IR Spectroscopy to Peptides, Proteins, and Hydrogen-Bond Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:8231–8251. doi: 10.1021/jp8113978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Urbanek DC, Vorobyev DY, Serrano AL, Gai F, Hochstrasser RM. The Two-Dimensional Vibrational Echo of a Nitrile Probe of the Villin HP35 Protein. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:3311–3315. doi: 10.1021/jz101367d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Chung JK, Thielges MC, Fayer MD. Dynamics of the folded and unfolded villin headpiece (HP35) measured with ultrafast 2D IR vibrational echo spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:3578–3583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100587108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Thielges MC, Axup JY, Wong DB, Lee H, Chung JK, Schultz PG, Fayer MD. 2D IR Spectroscopy of Protein Dynamics Using Two Vibrational Labels - a Site-Specific Genetically Encoded Unnatural Amino Acid and an Active Site Ligand. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011 doi: 10.1021/jp206986v. DOI: 10.1021/jp206986v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zheng ML, Zheng DC, Wang J. Non-Native Side Chain IR Probe in Peptides: Ab Initio Computation and 1D and 2D IR Spectral Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:2327–2336. doi: 10.1021/jp912062c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Bunagan MR, Gao J, Kelly JW, Gai F. Probing the Folding Transition State Structure of the Villin Headpiece Subdomain via Side Chain and Backbone Mutagenesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7470–7476. doi: 10.1021/ja901860f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Weeks CL, Polishchuk A, Getahun Z, DeGrado WF, Spiro TG. Investigation of an Unnatural Amino Acid for Use as a Resonance Raman Probe: Detection Limits and Solvent and Temperature Dependence of the ν(C≡N) Band of 4-Cyanophenylalanine. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2008;39:1606–1613. doi: 10.1002/jrs.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Morales MM, Thompson WH. Molecular-level Mechanisms of Vibrational Frequency Shifts in a Polar Liquid. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:7597–7605. doi: 10.1021/jp201591c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Huang CY, Wang T, Gai F. Temperature Dependence of the CN Stretching Vibration of a Nitrile-Derivatized Phenylalanine in Water. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003;371:731–738. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Schultz KC, Supekova L, Ryu Y, Xie J, Perera R, Schultz PG. A Genetically Encoded Infrared Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13984–13985. doi: 10.1021/ja0636690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.McMahon HA, Alfieri KN, Clark CAA, Londergan CH. Cyanylated Cysteine: A Covalently Attached Vibrational Probe of Protein-Lipid Contacts. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:850–855. doi: 10.1021/jz1000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Edelstein L, Stetz MA, McMahon HA, Londergan CH. The Effects of α-Helical Structure and Cyanylated Cysteine on Each Other. J .Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:4931–4936. doi: 10.1021/jp101447r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Silverman LN, Pitzer ME, Ankomah PO, Boxer SG, Fenlon EE. Vibrational Stark Effect Probes for Nucleic Acids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:11611–11613. doi: 10.1021/jp0750912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ye S, Huber T, Vogel R, Sakmar TP. FTIR Analysis of GPCR Activation Using Azido Probes. Nature Chem. Biol. 2009;5:397–399. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Oh K-I, Lee J-H, Joo C, Han H, Cho M. β-Azidoalanine as an IR Probe: Application to Amyloid Aβ (16-22) Aggregation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:10352–10357. doi: 10.1021/jp801558k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Oh K-I, Kim W, Joo C, Yoo D-G, Han H, Hwang G-S, Cho M. Azido Gauche Effect on the Backbone Conformation of β-Azidoalanine Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:13021–13029. doi: 10.1021/jp107359m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Dutta S, Rock W, Cook RJ, Kohen A, Cheatum CM. Two-dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy of Azido-nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide in Water. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;135:055106–5. doi: 10.1063/1.3623418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]