Abstract

Context:

Diabetes care is complex, requiring motivated patients, providers, and systems that enable guideline-based preventative care processes, intensive risk-factor control, and positive lifestyle choices. However, care delivery in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) is hindered by a compendium of systemic and personal factors. While electronic medical records (EMR) and computerized clinical decision-support systems (CDSS) have held great promise as interventions that will overcome system-level challenges to improving evidence-based health care delivery, evaluation of these quality improvement interventions for diabetes care in LMICs is lacking.

Objective and Data Sources:

We reviewed the published medical literature (systematic search of MEDLINE database supplemented by manual searches) to assess the quantifiable and qualitative impacts of combined EMR–CDSS tools on physician performance and patient outcomes and their applicability in LMICs.

Study Selection and Data Extraction:

Inclusion criteria prespecified the population (type 1 or 2 diabetes patients), intervention (clinical EMR–CDSS tools with enhanced functionalities), and outcomes (any process, self-care, or patient-level data) of interest. Case, review, or methods reports and studies focused on nondiabetes, nonclinical, or in-patient uses of EMR–CDSS were excluded. Quantitative and qualitative data were extracted from studies by separate single reviewers, respectively, and relevant data were synthesized.

Results:

Thirty-three studies met inclusion criteria, originating exclusively from high-income country settings. Among predominantly experimental study designs, process improvements were consistently observed along with small, variable improvements in risk-factor control, compared with baseline and/or control groups (where applicable). Intervention benefits varied by baseline patient characteristics, features of the EMR–CDSS interventions, motivation and access to technology among patients and providers, and whether EMR–CDSS tools were combined with other quality improvement strategies (e.g., workflow changes, case managers, algorithms, incentives). Patients shared experiences of feeling empowered and benefiting from increased provider attention and feedback but also frustration with technical difficulties of EMR–CDSS tools. Providers reported more efficient and standardized processes plus continuity of care but also role tensions and “mechanization” of care.

Conclusions:

This narrative review supports EMR–CDSS tools as innovative conduits for structuring and standardizing care processes but also highlights setting and selection limitations of the evidence reviewed. In the context of limited resources, individual economic hardships, and lack of structured systems or trained human capital, this review reinforces the need for well-designed investigations evaluating the role and feasibility of technological interventions (customized to each LMIC's locality) in clinical decision making for diabetes care.

Keywords: clinical management, computerized clinical decision-support systems, diabetes mellitus, electronic medical records

Introduction

Diabetes is associated with diminished quality of life,disabling complications, high health care costs, and reduced life expectancy. The International Diabetes Federation currently estimates that 285 million people are affected by diabetes globally.1 Projected growth in diabetes burdens are being driven largely by transitioning sociodemographic, economic, and environmental circum-stances and will be felt most notably in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) that are experiencing these transitions rapidly.

For most chronic noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, the current aggregated evidence from large trials supports combining positive lifestyle choices (appropriate nutritional choices, regular physical exercise, plus tobacco avoidance and/or cessation)2–9 with intensive and multifaceted risk-factor management [i.e., intensively controlling blood pressure (BP) and lipid levels together]10–12 and preventative checks (e.g., annual eye, foot, and urine tests) to identify precursors of progression to complications [cardiovascular disease (CVD), retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease]. Despite robust trial evidence demonstrating efficacy of these measures to prevent and/or delay onset of these disabling and life-threatening complications, implementation of evidence-based interventions is far from optimal worldwide.13–17

Chronic disease care is rooted in complex interactions between providers, patients, and systems for routine health care,18 which necessitates measures that stand-ardize and enforce guideline-driven processes of care and empowered patient self-management. Ideally, clinical care for diabetes would be organized to be accessible, proactive, patient-centered,19 evidence-based,20,21 and comprehensive with embedded continuity and account-ability.22 Instead, there is great variability in LMIC health services—from fragmented, low-resource services to accredited, quality-assured, comprehensive care delivery operations.23 Context-specific and cost-effective models of efficient, integrated, and organized health care delivery are therefore needed in resource-constrained environments to optimize care and break the cycle of health and socioeconomic burdens perpetuated by silent epidemics such as diabetes.24

Health information technology (HIT), mainly comprising electronic medical records (EMR) and computerized clinical decision-support systems (CDSS), has been shown to improve health care quality (defined by adherence to guidelines and decreased errors), safety, and efficiency, and has been proposed as cost saving at the system level for chronic disease prevention and management.25–27 Electronic medical records store health information (including laboratory, imaging, and therapeutic histories and trends) and may be enhanced to varying degrees through the addition of the following complementary functions: (1) link to pharmacies for automated prescription ordering, (2) automated decision support (e.g., reminders and therapeutic prompts), and/or (3) automated admin- istrative processes (e.g., billing).21 In particular, integrating decision-support tools with EMRs provides an opportunity to improve quality of care delivery by linking updated, aggregated, patient-specific data to evidence-based guidelines and computing tailored recommendations at the point of care. These enhancements may elevate care delivery in general practice settings, offsetting disparities between generalist and specialist diabetes care.

Although CDSSs have been shown to improve physician performance, the literature is equivocal with regard to patient outcomes.28 Also, the evidence regarding the external validity (sustainability, cost-effectiveness, acceptability, and scalability)29 of applying these HIT interventions in low- resource settings has not been established.30 In this article, we review and synthesize the literature regarding combined EMR–CDSS tools for diabetes management. To make appropriate recommendations for LMIC settings, we also explore the parallel issues of costs and patient and provider perspectives on performance and implementation of HIT tools for clinical diabetes care.

Methods

We searched the MEDLINE electronic database (using PubMed) for published studies assessing EMR–CDSS for diabetes. We used medical subject heading terms related to diabetes (“diabetes mellitus”) and computerized systems in clinical care (“medical records systems, computerized” or “decision-support systems, clinical” or “decision-support systems, management”). The search was limited to studies published in English and those related to humans. Up to November 30, 2010, our electronic search revealed 389 articles. Specific, standardized criteria were applied during review and selection of studies. We supplemented our search with manual searches of relevant articles.

To be included in this review, studies must have reported on the following:

Adult or child populations with type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus;

Testing integrated EMR–CDSS tools for clinical diabetes care [defined as any “electronic or compu-terized medical record or registry with any enhanced functionalities (reminders, management prompts, automated prescriptions, self-care support, patient report generation, or provider feedback)”]; and

Relevant outcomes, defined as processes of care (regularity of preventative visits and laboratory testing), self-monitoring, medication compliance, patient outcomes (biochemical results, satisfaction, health-related quality of life, costs, or complications), or practice-level considerations (coordination of care, patient–provider interactions).

Predefined exclusion criteria include publications that involved the following:

Participants with gestational, secondary, or rare forms of diabetes;

Studies describing methods or technology designs for upcoming/ongoing studies;

Case studies and reviews regarding EMR–CDSS tools;

Use of EMR–CDSS tools for conditions other than diabetes or in-patient hospital care; and

Utilization of HIT and computerized systems for purposes other than direct clinical patient care (e.g., identification of at-risk individuals from databases).

Study designs such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental designs (pre–post studies, controlled or uncontrolled), observational studies, retrospective audits, and qualitative evaluations were deemed acceptable. There were no limits on setting and timing of study publications included.

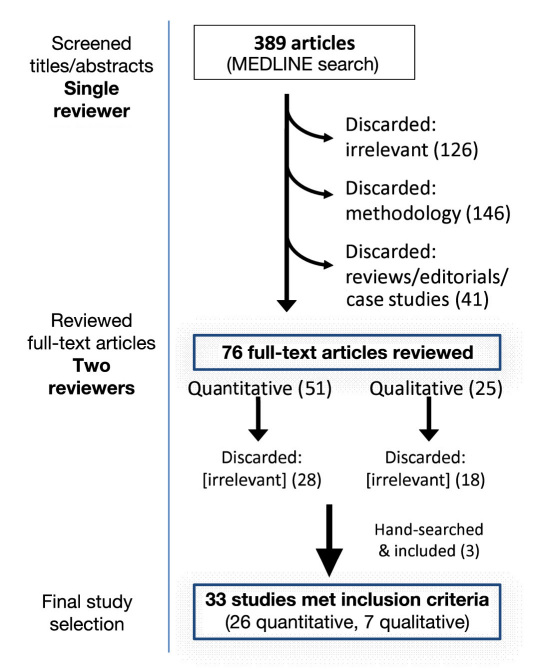

Figure 1 shows the search and study sorting process that led to full-text reviews of 76 study publications and inclusion of 33 studies (26 reporting quantitative indicators and 7 recounting qualitative themes). Studies were most commonly excluded because of a lack of relevance to quality of care or HIT (126), not testing direct outcomes of EMR–CDSS tools (146), or inappropriate scope of HIT use or study type (review, editorial; 41).

Figure 1.

Literature search and sorting process.

Analysis

Quantitative and qualitative data were extracted from study publications by separate single reviewers, respectively. All relevant data were tabulated and synthesized for reporting. This study was not a comprehensive meta-analysis nor a systematic review. Although formal assess-ments of study quality are not presented, this narrative review broadly examines the characteristics of study interventions, study designs, analytical approaches, and cautiously reports effect sizes.

Results

Studies Reporting Quantitative Outcomes

Detailed descriptions of the interventions, designs, and outcomes of studies reporting predominantly clinical care process indicators or measures of metabolic control among patients can be found in Table 1. Broadly, 22 of 26 studies originated from the United States, 3 were from Europe, and 1 from Canada. Study designs represented in this review included RCTs (9), cluster RCTs (4), quasi-experimental studies (8), retrospective (audit, chart review) comparisons (4), and a single cohort study. With 3 exceptions that were set in specialty diabetes clinics, studies were based in primary health care (PHC) clinics (defined to include internal medicine clinics), and mainly in urban environments. Study durations ranged from cross-sectional comparisons to 6 years of follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in Review (Arranged by Study Type and Year of Publication)a

| First author, country (year) | Setting | Population | Demographic characteristics | Study design | Intervention | Duration | Process outcomes | Intermediate outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MacLean,31 U.S. (2009) | 64 PHC clinics; more rural | 7412 with DM; duration of DM 10–10.4 years; 18–20% insulin users | 62.4–63.5 years; 48–50% males; 97% NHW | Cluster RCT | Vermont Diabetes Information System; provider and patient CDSS (reminders, alerts, quarterly reports) | 32 months | No change in A1C (~55–59%), lipid (71–79%), Cr (80–86%) testing; M-Alb tests ↑ (25–30% to 32–40%) | Mean A1C same (7–7.2); mean LDL ↓ (106.5 to 93.5); A1C <7 same (54–59%); LDL <100 increased (44.5% to 63.5%) |

| Cleveringa,32 Netherlands (2008) | 55 PHC clinics | 3391 T2DM; mean duration 5.4–5.8 years | 65 ± 11 years; 49% males; 97.7% NHW | Cluster RCT | 1 h consultation with nurse; CDSS with diagnostic and treatment algorithm + trimonthly reports | 12 months | — | 7.2% ↑ in A1C ≤7.0; 10.7% ↑ in SBP ≤140; 12.8% ↑ in TC ≤200; 12.4% ↑ in LDL ≤100; 8.6% ↑ in controlling all 3 RFs; controls: 2–7% ↑ in achieving targets |

| Smith,33 U.S. (2008) | 6 PHC clinics (97 PCPs) | 639 (92–94% T2DM); duration of DM 4 years; 32–33% on insulin | 60–62 years; 45–50% males; predominantly NHW | Cluster RCT | E-library of EBM + virtual consultations (specialists review records and send specific advice + EBM via email to PCP) | 21 months | Process score 56–58; aggregate optimal DM score (30 vs 18); more prescriptions of insulin, ACE/ARB, ASA, and statins at trial end | Median A1C ↓ in both arms (-0.6%); ~55% A1C <7%; median LDL ↓ in both arms 10–13 mg/dl; ~50% LDL <100; median SBP and DBP ↓ 1–2 mmHg in both arms; 41–46% BP <130/80 |

| Sequist,34 U.S. (2005) | 20 OP clinics (4 CHCs, 9 hospital-based OPDs, 7 practices; 194 PCPs) | 4529 with DM | 62.4 to 65.3 ± 14 years; 41–46% males; 54–64% NHW, 12–16% black, 9–22% Hispanic | Stratified RCT of clinics | EMR with electronic EBM reminders for DM or CAD care; algorithm searches EMR for results, problems, medications, and appropriately reminds PCPs in intervention arm | 6 months | Compared to controls, more likely to receive annual lipid profile (↑41%), 2 A1C tests/year (↑14%), annual eye exam (↑38%), and prescribed ACE/ARB (↑42%) or statins (↑10%) | — |

| Holbrook,35 Canada (2009) | 46 community-based PHC clinics | 511 T2DM; median duration of DM = 5.9 years; 16.8% taking insulin | 60.7 ± 12.5 years; 50.7% males | RCT | Provider-and-patient-accessed Web-based diabetes tracker (linked to EMR; automated reminders) | 6 months | 61.7% (I) vs 42.6% (C) showed improvement in process score (checks of A1C, LDL, BP, ALB, BMI, feet, exc, smoke); total score ↑ by 1.33 vs 0.06 | Mean A1C ↓ (-0.2 vs +0.2); SBP ↓ (4.7 mmHg vs +0.3); DBP ↓ (2.5 vs +0.7); LDL, no difference; composite score (+0.33 vs -0.16); |

| McCarrier,36 U.S. (2009) | DM specialty clinic | 77 insulin-treated T1DM with A1C >7.0% (≥2 visits in last 12months) | 37.3 ± 8.1 years; 68% male; 96% NHW | RCT | NCM-aided Web-based case management program (improves self-care activities) | 13.6–14 months | Self-efficacy score ↑ (+0.14 ± 0.62 vs -0.16 ± 0.62)b | Δ in A1C (-0.37 vs +0.11%, NS) |

| Ralston,37 U.S. (2009) | University general medicine clinic | 83 T2DM with A1C >7.0% (≥2 visit in last 12 months) | 57.3 years; 49–52% male; 73–89.7% NHW | RCT | NCM-aided Web-based case management program (self-care activities; feedback; patient and provider CDSS) | 12 months | — | Δ A1C (-0.9 vs +0.2%);b A1C <7% (33% vs 11%);b NS difference in SBP, DBP, TC |

| Grant,38 U.S. (2008) | 11 PHC practices (230 PCPs) | 244 with DM (A1C >7%); | 56 ± 12 years vs 59 ± 12; 50–57% male; 67–89% NHW | RCT | DM personal health record with online patient portal | 1.5 years | NS differences in A1C, BP, lipid profile checks | Mean A1C and LDL decreased pre–post; no between-group difference in A1C, BP, lipids |

| Augstein,39 Germany (2007) | 5 OP centers (3 PHC and 2 specialist) | 49 insulin-treated T1DM and T2DM; mean duration 14.2 years | 49.8 ± 11.3 vs 48.4 ± 15.5; 48–62.5% male; European Caucasians | multicenter RCT | Continuous glucose monitoring system ± Karlsburg Diabetes Management System | 3 months | — | Δ A1C (-0.34 vs +0.27%); mean A1C (7.41 vs 7.44); Δ mean sensor glucose (8.43 to 7.59 mmol) |

| Phillips,40 U.S. (2005) | Large public hospital PHC clinic | 4138 DM patients; mean duration 10 years; mean A1C 8.1% | 59 ± 12 years; 94% African American | RCT: 2x2 factorial | Hard copy of computer-generated reminders with patient-specific recommendations or face-to-face feedback (5 min/ 2 weeks) from specialists to residents or both | 15 months | More clinic visits, longer follow-up and interventions positively influenced reaching ADA targets | Mean A1C ↓ (-0.6 vs 0.2%); groups with feedback and both: BP↓ (-3.5 mmHg); all groups: LDL↓ (-15 mg/dl) |

| McMahon,41 U.S. (2005) | Boston Veteran's Affairs Center | 104 with DM, A1C ≥9% | ≥18 years | RCT | Given a laptop, glucose and BP monitoring devices, and access to Website with support; both groups took a DM education class | 12 months | — | Mean A1C↓ (-1.9 vs -1.4%); HDL↑ (3 vs 1 mg/dl); SBP↓ (-7 vs -10 mmHg); DBP↓(-6 vs -5 mmHg) |

| Meigs,27 U.S. (2003) | University PHC improvement project (26 providers) | 598 T2DM | — | RCT (physicians randomized) | Web-based diabetes disease management application for patients | 13 months | More A1C (+0.3 vs -0.04) and LDL (+0.2 vs +0.01) tests/year; more foot (+9.8 vs -0.7) exams/year | A1C (-0.23 vs +0.14); 1.4%↑ in BP ≤130/85; TC (-14.7 vs -9.4 mg/dl); LDL <100 ↑ (+20.3 vs 10.5%) |

| Lobach,42 U.S. (1994) | University family practice (and training) clinic | 359 with DM | — | RCT (physicians randomized) | Physician-accessed computer-assisted management protocol integrated with EMR and customized process guidelines based on patient data | 6 months | Median compliance scores (32.0% vs 15.6%) better in intervention group | — |

| O'Connor,43 U.S. (2005) | 2 PHC clinics | 122 with DM (identified from clinic records) | 60.6 vs 59.4; 54.4–58.5% males | CCT | EMR with automated prescriptions, linked laboratory data, prompts, reminders | 4 years | ↑ in ≥2 A1C/year (+31.5% vs no change); ↑ ≥1 LDL/year (+42.1% vs +26%) | No improvement in mean A1C level (control group improved) |

| Albisser,44 U.S. (1996) | 2 specialty clinics (HMO and private practice) | 204 T1DM and T2DM; “difficult-to-manage” cases (baseline A1C 8.9–10.1) | — | CCT, beta-testing study | 24 h voice-interactive electronic information system accessed by telephone, patient and physician accessed | 6 months | 55–69% of registrants were active users; 38,450 (HMO) and 22,257 (PP) calls | A1C ↓ by 1.0–1.3%; no change in metabolic control in nonusing participants; hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic crises fell 3-fold |

| Hunt,45 U.S. (2009) | PHC network (13 clinics, 71 providers) | 4265 continuously enrolled DM patients; A1C at baseline 7.11; 20% on insulin | 62 ± 15 years; 44% male | Pre–post | Implementation of EMR–CDSS (reminders, prompts, feedback) | 24 months | 7% ↑ A1C/year (83% to 90%); 1% ↑ BP/year (95% to 96%); 16% ↑ lipids/year (70 to 86%); 20% ↑ eye (to 59%) and 53% ↑ foot exams/year (to 79%); 5–14% ↑ in intensified glucose meds; 22%, 15%, and 34%↑ in statins, ACE/ARB, and aspirin use, respectively | Mean A1C same; 3% ↑ in A1C ≤7.0 (to 50%); BP↓ (-5/3 mmHg); 22% ↑ in BP ≤130/80 (~52%) 24% ↑ in LDL ≤100 (~56%); mean LDL ↓ (-13 mg/dl) |

| Ciemins,46 U.S. (2009) | 3 PHC clinics (28 PCPs) | 495 DM patients selected from registry; 83% had HTN, 70% had dyslipidemia | 64 ± 12 years; 45% males | Pre–post (2 phase) | “low dose” = targeted education for clinic staff + patients; “high dose” = fully functional EMR (registry, provider alerting, documenting, trend reports) | 6 years | 15.6% ↑ lipid profiles/year; 31.8% ↑ in eye exams/year; 43.5%↑ in foot exams/year; 32.5% ↑ in renal screens/year; 34.9% ↑ receiving all 3 | 18.3%↑ A1C <7.0%; 23.5%↑LDL <100 mg/dl; 17% ↑ BP <130/80; 27.4% ↑ in ≥ 2 RF control |

| Pollard,47 U.S. (2009) | 6 rural health centers (Medicaid, Medicare, state subsidies) | 661 DM (95% T2DM) | 60.2 years; 38% male | QE controlled, pre–post | Chronic disease electronic management system (same as WA state); classified by low/medium/high frequency registry use | 12 months | 0–16% ↑ ≥1 A1C test /year; 0–19%↑ ≥1 lipid profile/year; 18–20% ↑ in foot checks; 12–19% ↑ in eye checks; 10–60% ↑ nutrition advice | 2–3% more achieved A1C control; 8–35% more achieved LDL control, 0–19% more achieved optimal HDL and TG levels |

| Welch,48 U.S. (2007) | 4 CHC practices (1 PHC, 3 multi-specialty), and 50 comparison practices of national HMO | 6790–8022 | 4 populations (CAD, DM, HTN, dyslipidemia) | QE controlled, pre–post | 3 practices had EMRs integrated with laboratories, imaging, and decision support (1 did not) | 12 months | 5% ↑ (to 12%) in ≥2 A1C/year compared to -1% in control; 5% ↓ (to 35%) in ≥1 M-Alb check/year compared to +8%; 9% ↓ (to 36%) in eye exams/year compared to -2%; +29% ↑ in guideline adherence (vs ~5%) | 2% ↑ (to 59%) in self-monitoring compared to -4% in controls; 2% ↓ (to 64%) in those taking ACE/ARB compared to -10%) |

| McCulloch,49 U.S. (1998) | 25 PHC clinics of non-profit HMO | 1000 yearly with DM | — | Pre–post (60 practices selected randomly out of 227) | Modified system of care (Diabetes Roadmap): registry with summary reports, provider feedback, specialist team visits, online guidelines, self-management support | 3 years | 19% ↑ ≥1 A1C/year (to ~92%); 15% ↑ eye exam/year (~70%); 64% ↑ foot exam/year (~82%); 50% ↑ M-Alb/year (to ~68%) | Mean A1C ↓ (-0.5% over 2 years); 68% A1C ≤8.0 |

| Club Diabete Sicili,50 Italy (2008) | 22 DM OP clinics | 12,000 with DM | 65 ± 12 years; 49.0% male | Cohort | EMR system (EuroTouch) with enhanced functionalities | 4.8 years | 19.5% ↑ ≥1 A1C test/year; 6.6% ↑ in ≥1 BP test/year; 24.1% ↑ ≥1 lipid profile/year; 23.6% ↑ in M-Alb checks | Mean A1C (-0.5%); 16.6% ↑ in A1C ≤7.0; 10.7%↑ in BP ≤130/85; 24.7% ↑ in LDL ≤100 |

| Weber,51 U.S. (2007) | 38 PHC clinics | 18,511–19,494 with DM (selected from registry) | 63 years; 42.2% male | Database query | EMR-based registry with CDSS, audits, feedback; physicians incentivized with bonuses | — | 5% ↑ A1C tests/6 months; 7% ↑ LDL tests/6 months; 29% ↑ M-Alb tests; 15% and 24% ↑ in influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations/year | 2.6% ↑ in A1C ≤7.0; 4.2% ↑ in BP ≤130/80 |

| Smith,52 U.S. (1998) | Specialty DM clinic (19 endocrinologists + 1 NCM) | 82 T1DM (17%) and T2DM (83%) | 60–62.4 ± 12–17 years; 20–25% male | Comparative chart review | Diabetes Electronic Management System | — | BP checks (3.6 vs 2.7);b ≥1 A1C/year (76.9 vs 51.2%);b ≥1 lipid/year (71.8% vs 65.1%); foot exams (2.9 vs 1.8);c eye exams (64.1% vs 65.1%); urine M-Alb (30.8% vs 27.9%) | Mean A1C (9.7% vs 10.2%); mean DBP (80.6 vs 93.6);b mean SBP (138.3 vs 140.9 mmHg) |

| Domurat,53 U.S. (1999) | Managed care practice | 1399 high-risk DM cases | 57.0 ± 15.9 to 62.9 ± 10.6; 40–52% male | Comparative retrospective | Computer-supported team management | — | ≥1 A1C/year (84% vs 51%);c ≥1 lipids/year (75% vs 49%);c urine M-Alb (51% vs 7%)c | A1C in goal (42.4%); mean BP (139/76 vs 146/82 mmHg)c |

| East,54 U.S. (2003) | Free community clinic | 145 with DM | 18–62 years; 33–43% male; 61–79% Hispanic | Comparative retrospective chart review | Cardiovascular/Diabetes Electronic Management System | 6 months | ≥1 A1C/year (79.3% vs 87.3%);b ≥1 lipids/year (74.4% vs 74.6%); foot (26.8% vs 20.6%);c eye exams (56.1% vs 49.2%) | — |

| Friedman,55 U.S. (1998) | Managed care PHC setting | 1457 DM patients, health plan members | 31–64 years | Database query | Lovelace Diabetes Episodes of Care Program (multifaceted: team, practice guidelines, reminders, performance feedback) | 2 years | ≥1 A1C/year ↑ 12% (to 90%); ≥1 eye exam/year ↑ 5.3% (to 52.6%) over 2 years | A1C reduced (-1.8%) from 12.2% to 10.4% over 2 years |

PCP, primary care provider; OP, outpatient; CHC, community health clinic; OPD, outpatient department; DM, diabetes mellitus; HMO, health management organization; EBM, evidence-based messages; I, intervention arm; C, control arm; NHW, non-Hispanic white; CCT, controlled clinical trial; QE, quasi-experimental study (pre–post, controlled or uncontrolled); T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; CAD, coronary artery disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; M-Alb, microalbuminuria; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ↓, decrease(d); ↑, increase(d); Δ, change; NS, nonsignificant; ADA, American Diabetes Association; BMI, body mass index; RF, risk factor; exc, exercise; Cr, serum creatinin; h, hour; -, not reported.

Statistically significant, p < .05.

Highly statistically significant, p < .001.

Seven studies evaluated EMR–CDSS tools with combined patient and provider access portals. A total of 10 studies tested quality improvement strategies [EMR–CDSS with complementary quality improvement components (e.g., nurse case managers (NCMs), clinic workflow changes, specialist consultations, and/or physician incentives)].

Processes of Care and Clinical Outcomes

A total of 21 studies reported any clinical care process indicators [either proportions achieving process targets or mean number of biochemical (regular BP, lipid, glycemic control, or hemoglobin A1c [A1C] checks) and preventative examinations (annual foot, eye, urine examinations) or used process scoring] and reported either pre- and post-intervention or between-group (intensive and control) levels. Studies reported either proportions of participants achieving biochemical risk-factor control targets or the mean achieved risk-factor levels, with only 5 reporting neither.

Improvements in process outcomes associated with EMR–CDSS implementation ranged from no difference to approximately 30% increases in percentage receiving annual A1C, BP, lipid, foot, urine, and eye examinations between groups or pre- and post-intervention. Changes in glycemic control varied from no difference to 1.8% point reduction from baseline (with varied reporting and levels of statistical significance). The vast majority of studies demonstrated A1C reductions in the order of 0.3–0.9% points over the duration of a year. Also, up to a 20% greater achievement of A1C targets was noted either post-intervention or in those allocated to intervention groups. During follow-up, BP control among participants ranged from no change up to either a 10/13 mm Hg reduction in BP from baseline or 22% increases in proportion of participants achieving BP goals. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) reductions were observed up to 15 mg/dl along with 8–35% more participants achieving LDL <100 mg/dl. Very few studies reported changes in high-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, or triglyceride levels.

Impacts: Clinical Endpoints and Costs

No studies reported hard clinical endpoints (CVD events, diabetes-related complications, or mortality). One single report tallied the number of hypoglycemic or hyper-glycemic crises.

A total of five studies reported data related to costs and/or savings associated with interventions used, out of which one contained estimates from the mid 1990s. Themes that emerged from these studies are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Themes Emerging from Studies Reporting Cost Data

| • | Initial resource inputs to implement EMR–CDSS and associated disruptions impose high upfront costs. |

| • | Longer-term use of EMR–CDSS may be associated with cost savings (reduced staff plus infrastructure needs)48 or increased costs for complementary services (e.g., NCMs used average of 4 h per week to update patient care plans based on CDSS prompts).37 |

| • | EMR–CDSS may contribute to decreased health service utilization (6.6% less outpatient and 23% less specialist visits with 17% less hospital admissions and 10% shorter in-patient stays reported in a multifaceted quality improvement strategy using EMR–CDSS)49 and costs ($288 lower outpatient costs and $2311 lower overall costs, despite increased short-term pharmacy costs where participants adhere to regimen-intensifying prompts and end up purchasing more therapies and services).33 |

Studies Reporting Qualitative Assessments

Descriptions of qualitative assessments of EMR–CDSS use in clinical diabetes care are reported in Table 3. Of seven studies examined, four were United States-based, two were conducted in the United Kingdom, and one in Canada. Except for one mailed, self-administered questionnaire, all other studies were based in PHC clinics. Study types and methods included case studies (inter-views, process observation, document review), pre–post evaluations (interviews and focus groups), and other one-time comparative observation or questionnaire studies.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Studies Included in Qualitative (Including Mixed Methods) Study Reviewa

| First author, country, (year) | Setting | Focus of assessment(s) | Sample characteristics | Methods | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MacPhail,56 U.S. (2009) | 4 Kaiser Permanente medical centers with different models of care | Role of comprehensive, integrated electronic health record in care coordination | 46 physicians and staff, 65 adult patients with DM (46% male, 55.8% college educated) | Case studies of 4 sites with different care delivery models using semistructured in-person interviews with a total of 46 physicians/staff and telephone interviews with 65 adult patients with DM | Site A: PCPs and RN–CDEs, team-based, diabetes-specific care; site B: PCPs with offsite regional disease management program; site C: PCPs and RNs, team-based, multiple chronic disease care; site D: family practice PCPs, IM PCPs with NCM or Endo RN. Across all models, physicians/staff acted sequentially and EMRs enabled continuity to coordinate care (i.e., secure message feature and chart notes avoided need to track down staff). 94% of providers were highly satisfied with availability of patient information, and 89% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with care coordination. Reports of uncoordinated care by 6/65 patients and 5/12 PCPs were attributed to differences of opinion, conflicting staff role expectations, and discipline-specific views of patient needs. | Multidisciplinary teams help address coordination challenges. Longitudinal care planning and structured communications points may address gaps in coordination. |

| Hess,57 U.S. (2007) | University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, ambulatory setting (3 University of Pittsburgh Medical Center pilot practices) | University of Pittsburgh Medical Center HealthTrak: Web-based patient portal to assist patients with DM self-management, connects patient and physicians | 39 T2DM patients; 51% male, 54 ± 12 years; 28% nonwhite; >80% college educated | 10 (5 pre, 5 post) focus groups to assess reactions to University of Pittsburgh Medical Center HealthTrak. Topics: living with DM, information access, patient–provider communication; Sep 2004–Jan 2007 | HealthTrak functionalities include secure, electronic communication, preventive health care reminders, and disease-specific information. During study, no significant change in number of patient encounters or telephone calls received in clinic, but number of HealthTrak messages increased. Participants appreciated communication outside of clinic hours, tracking tools (i.e., monitoring of blood glucose values), remote access to laboratory tests, and reminders. Patients frustrated when tests not released, messages not answered. Education resources not used frequently. | Integrated Web-based portals for patients can be beneficial. |

| Green,58 Canada (2006) | Vancouver Island Health Authority chronic disease management (CDM) collaborative | To identify critical success factors enabling effective and efficient chronic care management (with Web-based CDM flow sheets) | 30 community-based physicians of Vancouver Island Health Authority CDM Collaborative | Prospective case study of successful diabetes management models using key informant interviews with physicians, process observation, document review | Web-based CDM “toolkit” was a direct critical success factor that improved PCP practices by tracking patient care processes using evidence-based clinical practice guideline-based flow sheets. IT factor was one of a set of seven direct components, including health delivery system enhancements, organizational partnerships, funding mechanisms, project management, practice models, and formal knowledge translation practices. Indirect factors also identified. | Successful implementation of IT tools requires interrelated system factors. Improvement of CDM in PHC entails monitoring quality indicators over time, practices, patients. |

| Rhodes,59 U.K. (2006) | 9 general practices of varied models | Effects of nurse using computerized checklist on nurse–patient interaction during visit | 25 T2DM patients; 4 doctors and 9 nurses | Video-taped consultations between nurse and patient; preconsultation semistructured patient interviews (topics: DM history, current care, concerns, expectations) | Nurses' use of computerized checklist imposes a mechanical structure to visits, socializing the patient to a routine format and limiting patient-centered care. During consultations, nurses spent much time gazing at computer screen, questions dictated by checklist were out of context (not natural conversation flow), cutting patients' questions short to move onto other items, deviation from checklist discouraged. | Use of computerized checklist in routinization is important for quality assurance and improving efficiency. Yet a focus on biomedical audit risks dominated the agenda, giving little opportunity for patients to raise concerns and tailor therapy; may counteract empowerment of patients for optimal diabetes care. |

| Ralston,60 U.S. (2004) | University of Washington general medicine clinic (8 internists, case manager) | Pilot of Diabetes Care Model: Living with Diabetes program (Web-based patient management module) | 9 patients aged 45–65 years enrolled in the Living with Diabetes program | Pre- and post- interviews (semistructured) with patients at their homes (Oct 2001–Dec 2002); 3rd round of interviews with 6/9 patients to clarify themes | Six themes emerged: feeling that nonacute concerns are uniquely valued (normally delayed/not addressed well in office/phone), enhanced sense of security about health and care (more frequent attention from providers), frustration with unmet expectations (IT issues and communication with provider after data uploaded), feeling more able to manage, valuing feedback, and difficulty fitting program into activities of daily life. First 3 themes relevant for design of Web-based tools for DM/chronic diseases care. | Web-based programs provide patients with access to their records and promote convenient continuity of care outside of the clinic. Better patient–provider communication regarding expectations are required. |

| Rinkus,61 U.S. (2003) | University of Texas Houston Health Sciences Center, ambulatory medical clinic | Comparison of cognitive task analyses of record-keeping of nursing tasks using paper records versus electronic records | 2 nurse researchers in ambulatory setting | Task assessment of 2 nurses entering data of a fictitious patient case (to document patient teaching and adherence assessment of insulin administration) in paper and EMRs. | No difference between 2 groups for time–space analysis, because either task could only be performed at the same time/same place or different time/same place (i.e., during and after patient visit at clinic). Patterns in hierarchical; goals, operators, methods, selection; and work flow analyses generally highlighted benefits of EMR versus paper records: standardized template structure with prompts, improved legibility, accessible remotely, data easily aggregated and analyzed; overall less time to use EMR with exception of novice users. | In an integrated clinical information system, EMRs help nurse documentation by decreasing redundancy, improving accuracy, and accessibility to other team members. |

| Thompson,62 Ireland (2002) | U.K., British Diabetic Association members | Recordkeeping types and functionality in clinical settings | 545 British DNS (70% response rate); 25% hospital based, 6% community based, 69% both | Cross-sectional questionnaire (semistructured, postal); topics: practice details, computerized record systems, manual recordkeeping (specific, shared, patient held), good practice | Recordkeeping by DNS: 65% manual profession-specific record keeping, 21% shared/integrated (one set used by all, stored in patient records department), 13% computerized, 0.7% patient held. 66% of those using computerized systems agreed they are efficient versus 28% using profession-specific versus 26% using manual shared. 66% felt “seamless care” hindered by communication problems among providers (information not documented properly or shared, e.g., referrals/discharges/admissions/treatment changes/diagnoses. 80% using manual systems wanted improvements versus 52% of those using computerized systems. | Computerized recordkeeping is useful in bridging primary and secondary care, but other components are required, including multidisciplinary team involvement. |

PCP, primary care provider; RN, registered nurse; CDE, certified diabetes educator; IM, internal medicine; IT, information technology; DM, diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; CDM, chronic disease management; DNS, diabetic nurse specialists.

Interventions with patient-accessed EMR–CDSS portals were well received by patients. Patients reported feeling that their concerns were valued, feeling empowered (tracking laboratory values themselves), and benefiting from more provider attention and feedback, resulting in enhanced security about their health. Frustrations included difficulties with HIT and not receiving prompt responses from providers, as well as difficulties fitting programs into daily activities. Moreover, patient-accessed EMR–CDSS was associated with increased Web-message communications but no fewer patient visits or phone calls.

Outpatient providers adopting clinic-based EMR–CDSS tools found improved efficiency and standardization of patient care processes over paper records and better informational continuity among and between providers (improving care coordination overall). Difficulties included differences in provider opinions regarding patient needs, conflicting role expectations, and communication gaps where information was not properly documented or shared. One study highlighted poor patient–provider interactions during visits on account of EMR–CDSS prompts making consultations mechanical and reducing patient-centeredness.

Discussion

This review reveals a number of key themes regarding the impact and performance of EMR–CDSS for diabetes and its applicability in LMICs. However, it is important to consider the limitations of this review when inter- preting these findings. First, this compilation of studies includes vastly heterogeneous study designs, interventions, analytical methods, outcome indicators, and reporting. Second, the studies included were conducted exclusively in North America and Western Europe and may not offer generalizability for LMICs. Finally, searches were limited to a single database, which may have decreased the yield of relevant publications. To counteract this, we applied a comprehensive search strategy, utilized the leading medical literature database, and supplemented findings with manually searched articles.

Scope of Interventions

In this evaluation of computerized systems to support clinical decision-making, the authors noted that adoption of EMR–CDSS was associated with decreased interclinic or interprovider variability in processes and outcomes. Studies with multifaceted clinical care strategies [NCMs, workflow changes, enabling tools (patient information sheets, algorithms), financial incentives] had noticeably larger quantitative and qualitative effect sizes than those using isolated interventions, and we postulate that these better outcomes are related to targeting multiple levels (patients and providers). Our findings were consistent with other studies and guidelines that support structured, multifaceted diabetes management.63,64 The independent effects associated with each component intervention are unknown, as studies reviewed did not disaggregate the multifaceted interventions. In addition, decision-support tools with a greater number of features, interactive aspects, and patient-accessible portals were also associated with better outcomes.

Outcomes

Almost all studies reported key performance indicators that are accepted, evidence-based indicators reflecting care quality.64–66 However, differences in reporting (percentage achieving process or control targets versus mean levels) prevented an aggregated quantitative data synthesis. The lack of studies reporting hard clinical endpoints most likely reflects insufficient sample sizes or duration of follow-up observed. Also, the lack of estimates of anticipated reductions in complications also explains the dearth of cost-effectiveness or cost-savings assessments.

On balance, among the studies reviewed, there were more consistent associations between EMR–CDSS adoption and improvements in clinical care processes than improved risk-factor control, consistent with a previous review of computerized interventions for diabetes care.67 Most authors acknowledge that improved processes do not necessarily equate with reduced cardiometabolic risk. The studies reviewed allude to improvements in health service utilization and risk-factor control among those with poorer baseline risk profiles, suggesting that quality improvement interventions may have greater benefit where there is still room for improvement. Conversely, in systems where guideline adherence is near optimal, further improvements are not observed with EMR–CDSS interventions.47,68 Lastly, a third of studies meeting inclusion criteria did not report both care process measures and laboratory outcomes, which highlights a need for standard evaluation metrics to compare HIT interventions and assess key implementation and maintenance factors (e.g., cost, reach, implementation).25

Analysis of Studies

Study design has a profound bearing on inferences that can be derived from research data. In particular, the studies in this review represent a mix of designs: uncontrolled pre–post studies and controlled trials with groups not receiving the intervention also experiencing process and control improvements. Taken together, these points allude to an overestimated effect size associated with the core intervention because these changes could conceivably be related to general improvements in awareness and care delivery over time. However, these criticisms may be counterbalanced by dilution of the intervention's effects where contamination was present (i.e., minimizing the aggregate differences observed between intensive and control groups because of contact between individuals in each arm). Also, individual effect sizes may be underestimates when derived from study populations in cluster RCTs, as randomization is at the clinic level while outcomes are measured for individual participants.

The generalizability that can be drawn from these findings is strongly associated with selection of participating individuals and/or clinics. Participants in all but one study (with type 1 diabetes patients) had mean age between 55 and 65 years, were predominantly of non-Hispanic White origin, and generally represented populations with access to health services and technology (insured, educated, regular computer/Internet users). Also, practitioners in these studies were more motivated (practices self-selected into some studies); other studies only analyzed data from participants with sufficient follow-ups (isolating those who exhibit high compliance); and very few studies employed intention-to-treat analyses or reported loss-to-follow-up. Also, performance-based financial incentives used in some studies may encourage both positive and negative provider behaviors—either enhancing care practices for the duration that incentives are available or, alternatively, “selecting” patients with more favorable profiles to accrue more compensation. Other reviews on HIT in diabetes care have found similar limitations.67,69 Lastly, some authors skeptically note that the effects observed may simply reflect better documentation by providers, with no real improvement in processes; however, this critique does not account for real observed reductions in risk-factor levels.

Applicability to Low- and Middle-Income Country Settings

Considering the escalating diabetes burden and suboptimal adherence to management guidelines globally,13,15,70–72 there are several areas where EMR–CDSS implementation may provide value in LMICs:21,28,73

Structuring services and standardizing care processes (e.g., standard patient visit record format);

Emphasis on comprehensive multifactorial risk reduction (e.g., guideline-based patient-tailored prompts to physicians to consider all risks and/or intensify treatments);

Enhancing continuity (access to complete current and past patient data) and integration of clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic information (e.g., medi-cation history, drug interactions, allergies) among different providers in different settings, potentially reducing unnecessary costs of repeated diagnostic examinations;

Empowering patients (e.g., accessible health infor-mation resources and computerized reminders for follow-ups); and

Computerized administration of processes (e.g., billing, scheduling).

As in previous reviews of general and diabetes-specific utilization of HIT, our review also found that most published research has occurred in high-resource settings.25,74,75 However, experience from diabetes clinical trials conducted in LMICs (e.g., ADVANCE trial in India) show similar outcomes as high-income country trials. As such, extrapolation of high-income setting findings to LMIC settings seems reasonable, provided that there is understanding of the local context.

Low- and middle-income countries face major cost and organizational challenges—health care systems are complex with convoluted financing mechanics and systemic frailties (e.g., deficiencies of structure, referral linkages, and trained manpower). In these contexts, implementing and maintaining HIT interventions represents high capital cost and delayed returns (although this may not be the case for private practices). Some LMIC regions may also have inadequate informatics-trained human resources to design, implement, and maintain such systems.30 Poor infrastructure (e.g., unreliable power supply and high-speed Internet connections), scarce HIT literacy, and culture-specific customs and perceptions regarding health and illness (e.g., it is unclear whether people in some settings will be amenable to undertaking intensive and costly treatment regimens to manage diabetes, a largely asymptomatic condition until onset of severe complications) may all impede adoption of HIT.76 Equally, care prompts need not always be intensive. Trials have shown that elderly patients with multiple comorbidities may not tolerate such therapeutic changes.77 The challenge in LMICs, therefore, is in the adaptation of HIT such that there is a balance between standardized, generic prompts and physician flexibility/discretion to make decisions that are most suitable for individual patients.

General considerations, even for high-resource settings, must include provisions to address privacy and/or security breaches associated with using HIT, maintaining HIT content, developing organizational/technical capabi-lities for managing HIT, and incorporating technologies seamlessly into clinic workflow to ensure communication and coordination of care without sacrificing patient focus.75,78–80

There are successful examples of EMR–CDSS utilization and health informatics capacity-building in LMICs, mostly for conditions other than diabetes. Examples can be found in sub-Saharan African countries81 (in particular Kenya,82,83 Cameroon,84 Mozambique,85 Rwanda,86,87 Uganda, and Malawi88) as well as Peru,89 Haiti,90 Brazil,89 Indonesia,91 and India.92 There may also be others that were not found in the mainstream academic literature.30,89,93,94 For example, a 2010 conference abstract describes a diabetes telemanagement system in Kerala, India, that integrates mobile phone and information technology tools and shows promise in enhancing self-management of blood glucose.93 With an enabling environment, implementing and sustaining EMR–CDSS in LMICs is possible94 and could have tangible benefits for diabetes care.95 In fact, similar to the current ubiquitous use of cell phone technology in lieu of landline telephone services, EMR–CDSS tools offer opportunities to leapfrog many infrastructural deficits in LMICs.96,97

Systematic reviews of diabetes management highlight the utility of HIT for improving patient care in the context of an integrated model.93,98 This is a key point that also emerged from our findings—organizing and delivering care for people with diabetes and other chronic diseases potentially requires more than just HIT. Complementary personnel or workflow changes are “enabling”—they have a significant role in motivating patient self-management, augmenting the effectiveness of EMR–CDSS tools. From our experiences in India where physicians indicate preference for paper-based consultation records, auxiliary health personnel offer a complementary role, adopting responsibility for data entry and managing software applications, freeing physicians of these duties, but also prompting physicians with computer-generated recommendation printouts.

Scalability and sustainability of these HIT interventions, which are still considered cost intensive, will depend on accumulation of more evidence accounting for health care delivery design, which varies across and within LMICs. For example, large nationalized health systems or insurance-based health care delivery schemes focus on metrics evaluating population-level benefits (reduction in complications, hospitalizations, and mortality); meanwhile, individuals paying out-of-pocket for enhanced technology-based care at private providers will evaluate tradeoffs differently. In either case, potential models of care need to be rigorously tested in LMIC settings, using appropriate study designs and factoring in appropriate duration of follow-up, minimization of biases, and cost-effectiveness evaluations.99 Lastly, generic HIT tools may not be appropriate for heterogeneous settings, so customizing tools to suit context-specific cultural variation, physician practices, and organizational norms may enhance adoption and implementation,100 while assessments of patient acceptability may identify the key features that promote successful self-care adherence.

Conclusions

Our review is based on studies among populations in fundamentally different countries and contexts than the range of cultures, settings, and circumstances that are pervasive across all LMICs. Broadly, EMR–CDSS offers important process benefits (accountability, reduced fragmentation) at the provider and clinic level, with modest improvements in terms of risk-factor control and acceptability among patients. Although models of care centered on EMR–CDSS may be replicable in LMIC settings, we recommend exercising caution and considering appropriate customization of solutions to fit contexts. For example, although our review points to using fully functional, interactive, and patient-accessible EMR–CDSS, it is not clear from these studies what level of functionality will be acceptable or even accessible by providers and patients in LMICs. We therefore advocate testing customized interventions that can be easily integrated without major infrastructural overhaul. Also, due to the “digital divide” (whereby access to Internet and computer technology is limited to highest socioeconomic strata patients), we recommend complementary inter-ventions in the form of trained nonphysician health workers to facilitate clinical care instead of patient-accessed portals for patient feedback.

We described the quality of studies and key characteristics that differentiate the interventions in these studies with a view to helping readers draw appropriate inferences from this evidence regarding technical efficiency of intervention delivery as well as identifying key gaps in the evidence accumulated to date. Although we reiterate the frailty of extrapolating from studies conducted entirely in high-income country settings, our hope is that this piece will have macrolevel benefits by stimulating greater investments in translation research of scalable strategies for high-quality diabetes care in LMICs.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (award no. HHSN268200900026C) and Fogarty International Center (award no.5R24TW00798) at the US National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- (BP)

blood pressure

- (CDSS)

computerized clinical decision-support system

- (CVD)

cardiovascular disease

- (EMR)

electronic medical record

- (A1C)

glycated hemoglobin

- (HIT)

health information technology

- (LDL)

low-density lipoprotein

- (LMIC)

low- and middle-income country

- (NCM)

nurse case manager

- (PHC)

primary health care

- (RCT)

randomized controlled trial

References:

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. 4th ed. 2009. Diabetes atlas. www.diabetesatlas.org. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manley SE, Stratton IM, Cull CA, Frighi V, Eeley EA, Matthews DR, Holman RR, Turner RC, Neil HA; United Kingdom Prospective Diabets Study Group. Effects of three months' diet after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes on plasma lipids and lipoproteins (UKPDS 45) Diabet Med. 2000;17(7):518–523. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kris-Etherton P, Eckel RH, Howard BV, St Jeor S, Bazzarre TL; Nutrition Committee Population Science Committee, Clinical Science Committee of the American Heart Association. AHA Science Advisory: Lyon Diet Heart Study. Benefits of a Mediterranean-style, National Cholesterol Education Program/American Heart Association Step I Dietary pattern on cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2001;103(13):1823–1825. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher GF, Balady GJ, Amsterdam EA, Chaitman B, Eckel R, Fleg J, Froelicher VF, Leon AS, Piña IL, Rodney R, Simons-Morton DA, Williams MA, Bazzarre T. Exercise standards for testing and training: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001;104(14):1694–1740. doi: 10.1161/hc3901.095960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA, Finkel T. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(7):593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner N, Kosiol S, Schiegl T, Ahlers P, Walenta K, Link A, Böhm M, Nickenig G. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(10):999–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laufs U, Werner N, Link A, Endres M, Wassmann S, Jürgens K, Miche E, Böhm M, Nickenig G. Physical training increases endothelial progenitor cells, inhibits neointima formation, and enhances angiogenesis. Circulation. 2004;109(2):220–226. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109141.48980.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohiuddin SM, Mooss AN, Hunter CB, Grollmes TL, Cloutier DA, Hilleman DE. Intensive smoking cessation intervention reduces mortality in high-risk smokers with cardiovascular disease. Chest. 2007;131(2):446–452. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Critchley JA, Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;290(1):86–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kempler P. Learning from large cardiovascular clinical trials: classical cardiovascular risk factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;68(Suppl 1):S43–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srikanth S, Deedwania P. Comprehensive risk reduction of cardiovascular risk factors in the diabetic patient: an integrated approach. Cardiol Clin. 2005;23(2):193–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnett AH. The importance of treating cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2008;5(1):9–14. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2008.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saaddine JB, Engelgau MM, Beckles GL, Gregg EW, Thompson TJ, Narayan KM. A diabetes report card for the United States: quality of care in the 1990s. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(8):565–574. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-8-200204160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckles GL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM, Herman WH, Aubert RE, Williamson DF. Population-based assessment of the level of care among adults with diabetes in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(9):1432–1438. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saydah SH, Fradkin J, Cowie CC. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA. 2004;291(3):335–342. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savage PJ. Treatment of diabetes mellitus to reduce its chronic cardiovascular complications. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1998;13(2):131–138. doi: 10.1097/00001573-199803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EUROASPIRE II Study Group. Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries; principal results from EUROASPIRE II Euro Heart Survey Programme. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(7):554–572. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayan KM, Benjamin E, Gregg EW, Norris SL, Engelgau MM. Diabetes translation research: where are we and where do we want to be? Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(11):958–963. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA. Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1611–1625. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betancourt JR. Improving quality and achieving equity: the role of cultural competence in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in health care. The Commonwealth Fund. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. http://books.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10027#toc. Accessed February 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gwatkin DR, Bhuiya A, Victora CG. Making health systems more equitable. Lancet. 2004;364(9441):1273–1280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Directorate for Employment, Labour, and Social Affairs. Policy note: health policy in Mexico. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/51/60/38120478.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2010.

- 24.Ali MK, Narayan KM, Mohan V. Innovative research for equitable diabetes care in India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;86(3):155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillestad R, Bigelow J, Bower A, Girosi F, Meili R, Scoville R, Taylor R. Can electronic medical record systems transform health care? Potential health benefits, savings, and costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(5):1103–1117. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meigs JB, Cagliero E, Dubey A, Murphy-Sheehy P, Gildesgame C, Chueh H, Barry MJ, Singer DE, Nathan DM. A controlled trial of web-based diabetes disease management: the MGH diabetes primary care improvement project. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):750–757. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, Sam J, Haynes RB. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1223–1238. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalkidou K, Levine R, Dillon A. Helping poorer countries make locally informed health decisions. BMJ. 2010;341:c3651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams F, Boren SA. The role of the electronic medical record (EMR) in care delivery development in developing countries: a systematic review. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16(2):139–145. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v16i2.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maclean CD, Gagnon M, Callas P, Littenberg B. The Vermont diabetes information system: a cluster randomized trial of a population based decision support system. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1303–1310. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1147-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cleveringa FG, Gorter KJ, van den Donk M, Rutten GE. Combined task delegation, computerized decision support, and feedback improve cardiovascular risk for type 2 diabetic patients: a cluster randomized trial in primary care. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2273–2275. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SA, Shah ND, Bryant SC, Christianson TJ, Bjornsen SS, Giesler PD, Krause K, Erwin PJ, Montori VM; Evidens Research Group. Chronic care model and shared care in diabetes: randomized trial of an electronic decision support system. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(7):747–757. doi: 10.4065/83.7.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sequist TD, Gandhi TK, Karson AS, Fiskio JM, Bugbee D, Sperling M, Cook EF, Orav EJ, Fairchild DG, Bates DW. A randomized trial of electronic clinical reminders to improve quality of care for diabetes and coronary artery disease. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(4):431–437. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holbrook A, Thabane L, Keshavjee K, Dolovich L, Bernstein B, Chan D, Troyan S, Foster G, Gerstein H; COMPETE II Investigators. Individualized electronic decision support and reminders to improve diabetes care in the community: COMPETE II randomized trial. CMAJ. 2009;181(1-2):37–44. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarrier KP, Ralston JD, Hirsch IB, Lewis G, Martin DP, Zimmerman FJ, Goldberg HI. Web-based collaborative care for type 1 diabetes: a pilot randomized trial. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11(4):211–217. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ralston JD, Hirsch IB, Hoath J, Mullen M, Cheadle A, Goldberg HI. Web-based collaborative care for type 2 diabetes: a pilot randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):234–239. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant RW, Wald JS, Schnipper JL, Gandhi TK, Poon EG, Orav EJ, Williams DH, Volk LA, Middleton B. Practice-linked online personal health records for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1776–1782. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Augstein P, Vogt L, Kohnert KD, Freyse EJ, Heinke P, Salzsieder E. Outpatient assessment of Karlsburg Diabetes Management System-based decision support. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(7):1704–1708. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips LS, Ziemer DC, Doyle JP, Barnes CS, Kolm P, Branch WT, Caudle JM, Cook CB, Dunbar VG, El-Kebbi IM, Gallina DL, Hayes RP, Miller CD, Rhee MK, Thompson DM, Watkins C. An endocrinologist-supported intervention aimed at providers improves diabetes management in a primary care site: improving primary care of African Americans with diabetes (IPCAAD) 7. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(10):2352–2360. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McMahon GT, Gomes HE, Hickson Hohne S, Hu TM, Levine BA, Conlin PR. Web-based care management in patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(7):1624–1629. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lobach DF, Hammond WE. Development and evaluation of a Computer-Assisted Management Protocol (CAMP): improved compliance with care guidelines for diabetes mellitus. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1994:787–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Connor PJ, Crain AL, Rush WA, Sperl-Hillen JM, Gutenkauf JJ, Duncan JE. Impact of an electronic medical record on diabetes quality of care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(4):300–306. doi: 10.1370/afm.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albisser AM, Harris RI, Sakkal S, Parson ID, Chao SC. Diabetes intervention in the information age. Med Inform (Lond) 1996;21(4):297–316. doi: 10.3109/14639239608999291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunt JS, Siemienczuk J, Gillanders W, LeBlanc BH, Rozenfeld Y, Bonin K, Pape G. The impact of a physician-directed health information technology system on diabetes outcomes in primary care: a pre- and post-implementation study. Inform Prim Care. 2009;17(3):165–174. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v17i3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ciemins EL, Coon PJ, Fowles JB, Min SJ. Beyond health information technology: critical factors necessary for effective diabetes disease management. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(3):452–460. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollard C, Bailey KA, Petitte T, Baus A, Swim M, Hendryx M. Electronic patient registries improve diabetes care and clinical outcomes in rural community health centers. J Rural Health. 2009;25(1):77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welch WP, Bazarko D, Ritten K, Burgess Y, Harmon R, Sandy LG. Electronic health records in four community physician practices: impact on quality and cost of care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(3):320–328. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCulloch DK, Price MJ, Hindmarsh M, Wagner EH. A population-based approach to diabetes management in a primary care setting: early results and lessons learned. Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Club Diabete Sicili. Five-year impact of a continuous quality improvement effort implemented by a network of diabetes outpatient clinics. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(1):57–62. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber V, Bloom F, Pierdon S, Wood C. Employing the electronic health record to improve diabetes care: a multifaceted intervention in an integrated delivery system. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):379–382. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0439-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith SA, Murphy ME, Huschka TR, Dinneen SF, Gorman CA, Zimmerman BR, Rizza RA, Naessens JM. Impact of a diabetes electronic management system on the care of patients seen in a subspecialty diabetes clinic. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(6):972–976. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.6.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Domurat ES. Diabetes managed care and clinical outcomes: the Harbor City, California Kaiser Permanente diabetes care system. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(10):1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.East J, Krishnamurthy P, Freed B, Nosovitski G. Impact of a diabetes electronic management system on patient care in a community clinic. Am J Med Qual. 2003;18(4):150–154. doi: 10.1177/106286060301800404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedman NM, Gleeson JM, Kent MJ, Foris M, Rodriguez DJ, Cypress M. Management of diabetes mellitus in the Lovelace Health Systems' EPISODES OF CARE program. Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacPhail LH, Neuwirth EB, Bellows J. Coordination of diabetes care in four delivery models using an electronic health record. Med Care. 2009;47(9):993–999. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819e1ffe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hess R, Bryce CL, Paone S, Fischer G, McTigue KM, Olshansky E, Zickmund S, Fitzgerald K, Siminerio L. Exploring challenges and potentials of personal health records in diabetes self-management: implementation and initial assessment. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13(5):509–517. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green CJ, Fortin P, Maclure M, Macgregor A, Robinson S. Information system support as a critical success factor for chronic disease management: necessary but not sufficient. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75(12):818–828. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rhodes P, Langdon M, Rowley E, Wright J, Small N. What does the use of a computerized checklist mean for patient-centered care? The example of a routine diabetes review. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(3):353–376. doi: 10.1177/1049732305282396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ralston JD, Revere D, Robins LS, Goldberg HI. Patients' experience with a diabetes support programme based on an interactive electronic medical record: qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7449):1159. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rinkus SM, Chitwood A. Cognitive analyses of a paper medical record and electronic medical record on the documentation of two nursing tasks: patient education and adherence assessment of insulin administration. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:657–661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thompson KA, Coates VE, McConnell CJ, Moles K. Documenting diabetes care: the diabetes nurse specialists' perspective. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(6):763–772. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, Wagner EH, Eijk JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD001481. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fleming BB, Greenfield S, Engelgau MM, Pogach LM, Clauser SB, Parrott MA. The Diabetes Quality Improvement Project: moving science into health policy to gain an edge on the diabetes epidemic. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1815–1820. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicolucci A, Greenfield S, Mattke S. Selecting indicators for the quality of diabetes care at the health systems level in OECD countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(Suppl 1):26–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Balas EA, Krishna S, Kretschmer RA, Cheek TR, Lobach DF, Boren SA. Computerized knowledge management in diabetes care. Med Care. 2004;42(6):610–621. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000128008.12117.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frijling BD, Lobo CM, Hulscher ME, Akkermans RP, Braspenning JC, Prins A, van der Wouden JC, Grol RP. Multifaceted support to improve clinical decision making in diabetes care: a randomized controlled trial in general practice. Diabet Med. 2002;19(10):836–842. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jackson CL, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Batts-Turner ML, Gary TL. A systematic review of interactive computer-assisted technology in diabetes care. Interactive information technology in diabetes care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(2):105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nagpal J, Bhartia A. Quality of diabetes care in the middle- and high-income group populace: the Delhi Diabetes Community (DEDICOM) survey. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2341–2348. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mohamed M; Diabcare-Asia 2003 Study Group. An audit on diabetes management in Asian patients treated by specialists: the Diabcare-Asia 1998 and 2003 studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(2):507–514. doi: 10.1185/030079908x261131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raheja BS, Kapur A, Bhoraskar A, Sathe SR, Jorgensen LN, Moorthi SR, Pendsey S, Sahay BK. DiabCare Asia–India Study: diabetes care in India–current status. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:717–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38398.500764.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baig AA, Wilkes AE, Davis AM, Peek ME, Huang ES, Bell DS, Chin MH. The use of quality improvement and health information technology approaches to improve diabetes outcomes in African American and Hispanic patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(5 Suppl):163S–197S. doi: 10.1177/1077558710374621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tomasi E, Facchini LA, Maia MF. Health information technology in primary health care in developing countries: a literature review. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):867–874. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nyamwaya D, Nordberg E, Oduol E. Socio-cultural information in support of local health planning: conclusions from a survey in rural Kenya. Int J Health Plann Manage. 1998;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1751(199801/03)13:1<27::AID-HPM498>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ali MK, Narayan KM, Tandon N. Diabetes & coronary heart disease: current perspectives. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132(5):584–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104–112. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ludwick DA, Doucette J. Adopting electronic medical records in primary care: lessons learned from health information systems implementation experience in seven countries. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McDonald CJ. The barriers to electronic medical record systems and how to overcome them. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(3):213–221. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1997.0040213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nucita A, Bernava GM, Bartolo M, Masi FD, Giglio P, Peroni M, Pizzimenti G, Palombi L. A global approach to the management of EMR (electronic medical records) of patients with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: the experience of DREAM software. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tierney WM, Rotich JK, Hannan TJ, Siika AM, Biondich PG, Mamlin BW, Nyandiko WM, Kimaiyo S, Wools-Kaloustian K, Sidle JE, Simiyu C, Kigotho E, Musick B, Mamlin JJ, Einterz RM. The AMPATH medical record system: creating, implementing, and sustaining an electronic medical record system to support HIV/AIDS care in western Kenya. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129(Pt 1):372–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hannan TJ, Tierney WM, Rotich JK, Odero WW, Smith F, Mamlin JJ, Einterz RM. The MOSORIOT medical record system (MMRS) phase I to phase II implementation: an outpatient computer-based medical record system in rural Kenya. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001;84(Pt 1):619–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kamadjeu RM, Tapang EM, Moluh RN. Designing and implementing an electronic health record system in primary care practice in sub-Saharan Africa: a case study from Cameroon. Inform Prim Care. 2005;13(3):179–186. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v13i3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Manders EJ, José E, Solis M, Burlison J, Nhampossa JL, Moon T. Implementing OpenMRS for patient monitoring in an HIV/AIDS care and treatment program in rural Mozambique. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;160(Pt 1):411–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Allen C, Jazayeri D, Miranda J, Biondich PG, Mamlin BW, Wolfe BA, Seebregts C, Lesh N, Tierney WM, Fraser HS. Experience in implementing the OpenMRS medical record system to support HIV treatment in Rwanda. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129(Pt 1):382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seymour RP, Tang A, DeRiggi J, Munyaburanga C, Cuckovitch R, Nyirishema P, Fraser HS. Training software developers for electronic medical records in Rwanda. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;160(Pt 1):585–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Douglas GP, Deula RA, Connor SE. The Lilongwe Central Hospital Patient Management Information System: a success in computer-based order entry where one might least expect it. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fraser HS, Biondich P, Moodley D, Choi S, Mamlin BW, Szolovits P. Implementing electronic medical record systems in developing countries. Inform Prim Care. 2005;13(2):83–95. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v13i2.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fraser HS, Jazayeri D, Nevil P, Karacaoglu Y, Farmer PE, Lyon E, Fawzi MK, Leandre F, Choi SS, Mukherjee JS. An information system and medical record to support HIV treatment in rural Haiti. BMJ. 2004;329(7475):1142–1146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pambudi IT, Hayasaka T, Tsubota K, Wada S, Yamaguchi T. Patient Record Information System (PaRIS) for primary health care centers in Indonesia. Technol Health Care. 2004;12(4):347–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anantraman V, Mikkelsen T, Khilnani R, Kumar VS, Pentland A, Ohno-Machado L. Open source handheld-based EMR for paramedics working in rural areas. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:12–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]