Abstract

Adipocypte fatty acid–binding protein-4 (FABP4/adipocyte P2) may play a central role in energy metabolism and inflammation. In animal models, defects of the aP2 gene (aP2–/–) partially protected against the development of obesity-related insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. However, it is unclear whether common genetic variation in FABP4 gene contributes to risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D) or diabetes-related metabolic traits in humans. We comprehensively assess the genetic associations of variants in the FABP4 gene with T2D risk and diabetes-associated biomarkers in a prospective study of 1,529 cases and 2,147 controls among postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years who enrolled in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS). We selected and genotyped a total of 11 haplotype-tagging single-nucleotide polymorphisms (tSNPs) spanning 41.3 kb across FABP4 in all samples. None of the SNPs and their derived haplotypes showed significant association with T2D risk. There were no significant associations between SNPs and plasma levels of inflammatory and endothelial biomarkers, including C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), E-selectin, and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1). Among African-American women, several SNPs were significantly associated with lower levels of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), especially among those with incident T2D. On average, plasma levels of VCAM-1 were significantly lower among carriers of each minor allele at rs1486004(C/T; −1.08 ng/ml, P = 0.01), rs7017115(A/G; −1.07 ng/ml, P = 0.02), and rs2290201(C/T; −1.12 ng/ml, P = 0.002) as compared with the homozygotes of the common allele, respectively. After adjusting for multiple testing, carriers of the rs2290201 minor allele remained significantly associated with decreasing levels of plasma VCAM-1 in these women (P = 0.02). In conclusion, our finding from a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women did not support the notion that common genetic variants in the FABP4 gene may trigger increased risk of T2D. The observed significant association between reduced VCAM-1 levels and FABP4 genotypes in African-American women warrant further confirmation.

INTRODUCTION

Fatty acid–binding protein-4 (FABP4), also known as adipocyte FABP (AFABP) and adipocyte P2, is highly expressed in adipocytes and macrophages. FABP4 is regulated during adipocytes differentiation, and its mRNA is transcriptionally controlled by fatty acids, nuclear hormone receptors, perosisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonists, insulin and liver X receptor (1–4), all of which have been shown to play an important regulatory role in inflammation and energy metabolism. Recently, deficiency of FABP4 has been correlated with plasma lipid levels, especially as a protective factor against atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease risk (5–9). In animal models, a modest increase in insulin sensitivity has been exhibited in obese mice with FABP4 deficiency (10–12). However, little is known about the association between the genetic variants in FABP4 and type 2 diabetes (T2D) risk in human population.

Therefore, we comprehensively assess the genetic associations of variants in the FABP4 gene with T2D risk and diabetes-associated biomarkers in a nested case–control study of postmenopausal women aged between 50 and 79 years who enrolled in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS). We selected and genotyped a total of 11 haplotype-tagging single-nucleotide polymorphisms (tSNPs) spanning 41.3 kb across FABP4 in all samples.

Furthermore, we investigated whether and to what extent the FABP4 variants affect circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) and endothelial adhesion molecules (including E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1)). These data may help to elucidate the relevant metabolic mechanisms underlying the FABP4 gene and T2D (13,14).

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Study participants

The WHI-OS is a longitudinal study designed to examine the association between clinical, socioeconomic, behavioral, and dietary risk factors with subsequent incidence of health outcomes, including cardio vascular disease and diabetes. Details regarding the case–control study design have been described elsewhere (15,16). The study has been reviewed and approved by human subjects review committees at each participating institution, and signed informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Between September 1994 and December 1998, the WHI-OS enrolled 93,676 postmenopausal women aged 50–79, and ~82,069 had no prior history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at baseline. WHI-OS participants were followed by annual mailed self-administered questionnaires and completed annual medical histories. Incident diabetes cases were identified on the basis of clinical cases that were diagnosed during the follow-up, with primary selection from those reporting treatment with hypoglycemic medication (insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents) and hypoglycemic medication confirmed at the clinic visit at the 3rd year of follow-up. Following the principle of risk-set sampling, for each new case, controls were selected randomly from women who remained free of diabetes at the time the case was identified during follow-up. A total of 1,529 cases were matched with 2,147 controls on age (±2.5 years), racial/ethnic group, clinical center (geographic location), time of blood draw (±0.10 h), and length of follow-up. The ethnic groups represented in this study include whites (n = 1,899), African Americans (n = 1,117), Hispanic/Latino Americans (n = 419), and Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders (n = 241). The 1:2 matching ratio was used for minorities to strengthen the power in these smaller samples (16).

Serum marker measurements

Serum inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α receptor 2, IL-6, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) and endothelial adhesion molecules (including E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1) were measured for each participants. The detail of serum marker measurements are described elsewhere (13,14). In brief, the coefficients of variation were 3.5% for TNF-α receptor 2, 7.6% for IL-6, 1.61% for high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, 6.5% for E-selectin, 6.7% for ICAM-1, and 8.9% for VCAM-1.

SNP frequency estimation and tagging SNP selection

As described previously (17), we implemented a two-stage approach to choose tSNPs for genotyping in our large case–control samples. The first stage consists of comprehensive common SNP discovery by genotyping a total of 25 SNPs in 244 samples randomly selected from the WHI-OS source population. The second stage involved selecting the tSNPs on the basis of linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns.

In the first stage, we surveyed common genetic variation using the National Center for Biotechnology Information database SNP supplemented by HapMap database (18). Our goal was to capture an initial set of SNPs with high SNP density covering the FABP4 gene as well as its 30-kbp 5′-upstream and 30-kbp 3′-downstream regions. In total, an initial set of 25 SNPs was selected on the basis of the following criteria: (i) functionality priority: nonsynonymous coding SNPs (cSNPs) and splicing-site SNPs (ssSNPs) were kept in the following order: cSNPs > ssSNPs > 5′-upstream SNPs > 3′-downstream SNPs > intronic SNPs; (ii) minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥5% in at least one ethnic group; and (iii) relatively evenly spaced across the genomic region (19).

In the second stage, we identified tSNPs on the basis of LD patterns of those 25 SNPs among 61 women from each ethnic population. Pairwise LD between SNPs was assessed using Lewontin's D′ statistic and the squared correlation statistic r2 (20). The Haploview program was used to calculate the LD coefficient and define haplotype blocks (21,22). We chose all common tSNPs with special focus on African and white American samples. First, we selected tSNPs in the African-American sample using the r2-based Tagger program (23). tSNPs in the African-American sample were chosen by finding the minimum set of SNPs with r2 ≥ 0.80 and MAF ≥5%. We then used backward trimming to reach a minimum set of tSNPs for other ethnic groups to ensure a sufficient, yet nonredundant, parsimonious set of tSNPs. From the initial dense set of 25 SNPs, a total of 10 tSNPs were eventually selected and genotyped in all case–control samples. An additional functional SNP, T87C (8,24,25), was also genotyped in all samples.

SNP genotyping method

For these 11 SNPs, large-scale genotyping was performed using the TaqMan allelic discrimination method. Specific primers and probes were custom designed by Applied Biosystems (ABI, Foster City, CA). Following PCR amplification, end-point fluorescence was read using the ABI Primer 7900 HT instrument, and genotypes were scored using SDS 2.2.2 Allelic Discrimination Software (Applied Biosystems). We genotyped 5% blind duplicated samples randomly selected to evaluate reproducibility. SNPs with higher genotyping discordant rate, higher missing genotype rate or deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium at P < 0.001 level were excluded.

Statistical analysis

We first estimated the MAF in the control samples for each ethnic group. The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test for each of the 11 SNPs was performed using the χ2-test (degrees of freedom = 1). We also tested for heterogeneity of genotype distributions across ethnicities by the χ2 test (degrees of freedom = 3; SAS, version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

In both single-SNP and haplotype-based analyses, we employed conditional multivariable logistic regression to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each genetic variant with T2D risk. We made adjustments for potential confounding variables by matching factors (such as age, clinical center, time of blood drawn, and ethnicity), BMI, cigarette smoking (never, past, and current), alcohol intake (never, past, and current), hormone replacement therapy usage (never, past, and current), and total metabolic equivalent value (the energy expended by a person at rest; 1 metabolic equivalent = 1 kcal/kg body weight/h) from recreational physical activity per week at baseline.

In single-SNP analyses, each SNP was coded as an additive, dominant, or recessive genetic model; in the estimation of allelic association with T2D risk, the likelihood ratio test (LRT) was used to test the interaction effect between the genotypes and ethnicity on T2D risk.

In haplotype-based analyses, the Haploview program was used to define the haplotype block patterns among SNPs (21,22). Only haplotypes with estimated frequencies ≥5% in the combined cases and controls were included for analyses. We tested for ethnic differences in haplotype- associated risks by performing an LRT following the inclusion of an interaction term between the risk haplotypes and ethnicity in the multivariable model. To examine the association between the resulting haplotype/haplotype combinations and T2D risk, the estimate of haplotype dosage was treated as a surrogate variable for the true haplotype. Global LRTs were used to examine whether the frequency distributions of the common haplotypes differed between cases and controls. We also adjusted for covariates that were adjusted in single-SNP association test. To increase the genomic coverage, we employed a sliding-window (window width = 3 SNPs) haplotype-based analysis. For each window, an omnibus LRT was used, which was a χ2 test (degrees of freedom = number of haplotypes in a particular window – 1). The test used a measure derived on the basis of difference of the logarithmic likelihood of two conditional logistic regression models: (i) the reduced model that does not contain the haplotype covariates, and (ii) the full model that contains the haplotype covariates.

In association tests with serum biomarkers analyses, we transformed all serum biomarker levels in log scale to enhance compliance with normality assumption. We then calculated the geometric mean differences and standard error by genotypes. To determine the effect of the genetic variant on each phenotype level, we calculated the geometric mean difference of these phenotype levels by genotypes using general linear models. Because the inheritance model used in the single-SNP analysis was the additive model, the result displayed a geometric mean biomarker-level increase per copy of the minor allele. All the linear models included matching factors and potential confounders (as mentioned previously) as covariates in each of the four ethnic groups. The regression models were performed among cases and controls separately. An LRT was also used to test the interaction effect between the genotypes and ethnicity on serum biomarkers. We also performed some subgroup analyses (biomarker groups) for FABP4-T2D.

To account for potential false-positive due to multiple comparisons in this study, we calculated the false discovery rate by incorporating all P values from multiple tests performed for SNPs and haplotypes in the association tests. The false-discovery-rate statistics were obtained for each P value, and the false-discovery-rate statistics with P ≤ 0.05 were considered as significant (26). Proc Multtest procedure in SAS 9.2 was used to obtain the adjusted P values.

RESULTS

Estimations of MAF and LD structures of 11 tSNPs in the FABP4 gene among controls

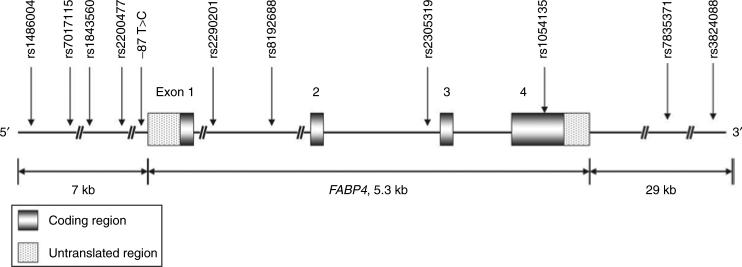

Figure 1 and Table 1 showed the characteristics of the 11 SNPs (one of them did not have an rs number). A total of 4 SNPs (rs2290201, rs8192688, rs2305319, and rs1054135) out of 11 (1 approximately every 1.3 kb) were located within the FABP4 gene (5.3-kbp long). All of the genotyped SNPs did not show statistically significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium at P < 0.001 between white, Hispanic, and Asian-American/Asian-Pacific Islanders controls. In addition, 2 out of 11 SNPs, that is, rs1486004 (5′ flanking region) and T87C (5′ promoter region), showed statistically significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium among African-American controls.

Figure 1.

The schematic presentation shows the position of 11 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that spans the adipocyte P2 (aP2) region genomic. These markers within the aP2 region consisted of one SNP in the 5′-promoter region (−87T>C), one missense SNP (rs1054135), and three intronic SNPs (rs2290201, rs8192688, and rs2305319). The missense SNP was without high linkage disequilibrium with other SNPs.

Table 1.

The location, relative distances, and MAF of 11 SNPs chosen in FABP4 genomic region

| MAF% |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP ID | Locationa | Relative distance (bp)a | Alleleb | White (n = 939) | Black (n = 746) | Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders (n = 165) | Hispanic (n = 279) | Pooled (n = 2,129) | P value for heterogeneity across ethnicityc |

| rs1486004 | 5′ flanking | 0 | C/T | 31.2 | 67.3 | 14.1 | 39.1 | 43.5 | <0.0001 |

| rs7017115 | 5′ flanking | 1,584 | A/G | 30.5 | 43.5 | 13.5 | 35.1 | 34.4 | 0.001 |

| rs1843560 | 5′ flanking | 5,919 | C/G | 31.4 | 56.9 | 14.6 | 38.0 | 39.9 | <0.0001 |

| rs2200477 | 5′ flanking | 6,349 | C/G | 31.6 | 75.8 | 14.1 | 40.4 | 46.9 | <0.0001 |

| T87C | 5′ promoter | 29,811 | T/C | 2.05 | 0.75 | 0 | 1.09 | 1.31 | 0.70 |

| rs2290201 | Intron 1 | 30,645 | C/T | 28.8 | 65.3 | 68.2 | 41.5 | 46.4 | <0.0001 |

| rs8192688 | Intron 1 | 32,498 | C/T | 16.6 | 9.12 | 0.30 | 10.8 | 12.0 | 0.002 |

| rs2305319 | Intron 2 | 33,473 | A/G | 17.0 | 16.6 | 7.01 | 16.6 | 16.0 | 0.17 |

| rs1054135 | Exon 4 | 34,587 | A/G | 6.8 | 24.3 | 11.8 | 9.64 | 13.7 | 0.003 |

| rs7835371 | 3′ UTR | 60,172 | A/T | 17.0 | 30.1 | 67.4 | 29.6 | 27.2 | <0.0001 |

| rs3824088 | 3′ UTR | 64,218 | A/G | 8.7 | 23.0 | 51.6 | 17.2 | 18.2 | <0.0001 |

Location and relative distance between SNPs are based on the contig position of contig NT_008183.18.

Major/minor allele.

P values were estimated by a χ2-test (degrees of freedom = 3) for genotype distribution across the four ethnic groups.

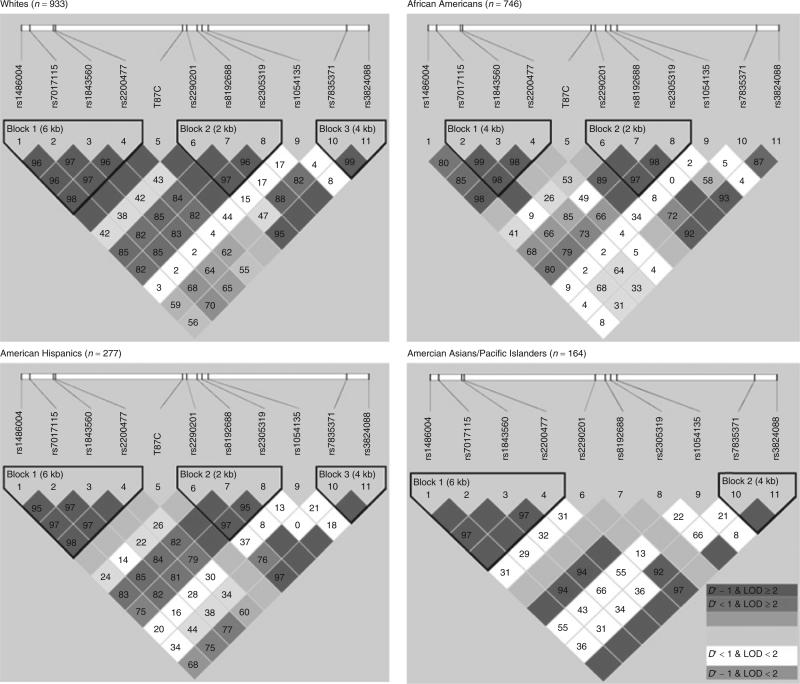

Figure 2 illustrates the LD structure and haplotype blocks, on the basis of 11 SNPs stratified by ethnicity among controls. With the exception of rs1054135, moderate-to-strong, pairwise LD was observed between most of the other genotyped SNPs. The locations and lengths of defined haplotype blocks varied slightly between ethnic groups. This partly reflects the differences in allele frequencies between groups. On the whole, three blocks with slightly different boundaries between four ethnic groups could be readily defined. The LD pattern within Block 1 (rs1486004, rs7017115, rs1843560, and rs2200477) was similar across all ethnic groups; however, the block did not include rs1486004 among African Americans. There was evidence for high LD pattern within Block 2 (rs2290201, rs8192688, and rs2305319), which consisted of SNPs within the FABP4 genomic region. This pattern was similar among whites, African Americans, and American Hispanics. The LD pattern within Block 3 (rs7835371 and rs3824088) was similar between whites, American Hispanics, and Asian Americans/Asian-Pacific Islanders. The following SNPs pairs were almost in perfect LD: rs1486004 and rs1843560 (each 5.92-kbp apart) among all groups (D′ = 0.969–0.976, r2 = 0.895–0.93), excluding African American (D′ = 0.851 and r2 = 0.454); rs1486004 and rs2200477 (each 6.35-kbp apart) among all groups (D′ = 0.982–1.00, r2 = 0.932–1.00), excluding African Americans (D′ = 0.986, r2 = 0.651); rs7017115 and rs1843560 (each 4.34-kbp apart) among all groups (D′ = 0.974–1.00, r2 = 0.851–0.91), excluding African Americans (D′ = 0.992, r2 = 0.577); and rs1843560 and rs2200477 (each 431-bp apart) among all groups (D′ = 0.967–1.00, r2 = 0.903–0.93), excluding African Americans (D′ = 0.994, r2 = 0.418).

Figure 2.

The haplotype blocks shown above define the linkage disequilibrium (LD) structures between the 11 tagging single-nucleotide polymorphisms (tSNPs) near or within the aP2 gene from four ethnic groups (whites, African Americans, American Hispanics, Asian Americans/Asian Pacific Islanders). The upper diagram gives the relative physical position of each SNP. The pairwise LD between all tSNPs is indicated by the respective diamonds for each SNP combination (with red illustrating strong LD (D′ > 0.8) and logarithm of odds score (LOD) ≥ 2). LD strength differences between the selected SNPs is determined by the 90% confidence limits of D′ statistics.

Single-marker association analysis

The association of each SNP with T2D risk in each ethnic group or in the pooled samples was investigated under the additive, dominant, and recessive genetic models. (The results under the additive genetic models are shown in Table 2.) No evidence of significant associations between all SNPs and T2D risk were found in all ethnic groups. Similar null associations were observed under either the dominant or the recessive genetic model (data not shown).

Table 2.

Single-SNP association studies of the 11 SNPs in the FABP4 genomic region with T2D risk

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP ID | Allele | White (947/952) | Black (366/751) | Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders (76/165) | Hispanic (140/279) | Pooled (1,529/2,147) |

| rs1486004 | T/C | 0.98 (0.80–1.19) | 0.91 (0.74–1.12) | 0.99 (0.49–1.99) | 0.86 (0.59–1.25) | 0.95 (0.83–1.07) |

| rs7017115 | A/G | 1.01 (0.82–1.24) | 1.07 (0.85–1.35) | 1.39 (0.72–2.67) | 0.84 (0.58–1.24) | 1.01 (0.89–1.16) |

| rs1843560 | G/C | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) | 0.96 (0.77–1.21) | 1.00 (0.51–1.96) | 0.79 (0.54–1.15) | 0.95 (0.83–1.08) |

| rs2200477 | G/C | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.79 (0.62–1.01) | 1.22 (0.64–2.32) | 0.89 (0.62–1.27) | 0.90 (0.79–1.03) |

| T87C | T/C | 1.80 (0.87–3.75) | 0.62 (0.14–2.65) | — b | 0.69 (0.11–4.17) | 1.26 (0.74–2.16) |

| rs2290201 | C/T | 0.95 (0.77–1.17) | 1.04 (0.84–1.30) | 1.46 (0.90–2.38) | 0.98 (0.69–1.40) | 1.02 (0.90–1.16) |

| rs8192688 | C/T | 0.92 (0.72–1.18) | 1.15 (0.80–1.65) | — b | 0.83 (0.46–1.51) | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) |

| rs2305319 | A/G | 1.04 (0.82–1.34) | 1.02 (0.77–1.35) | 1.41 (0.57–3.52) | 0.76 (0.47–1.23) | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) |

| rs1054135 | G/A | 0.85 (0.59–1.24) | 1.07 (0.84–1.37) | 1.26 (0.62–2.55) | 0.67 (0.35–1.27) | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) |

| rs7835371 | T/A | 1.02 (0.79–1.31) | 1.02 (0.81–1.28) | 1.32 (0.82–2.12) | 0.85 (0.55–1.33) | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) |

| rs3824088 | A/G | 1.08 (0.76–1.54) | 0.98 (0.75–1.28) | 1.26 (0.75–2.12) | 1.38 (0.76–2.49) | 1.09 (0.91–1.31) |

Odds ratios are estimated using conditional logistic regression adjusted for age, clinical center, time of blood draw, ethnicity, and other confounders, including HRT use, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, BMI, and physical activity. The numbers of participants (both cases and controls) were included in the parenthesis.

Result is difficult to interpret because of small sample within strata.

Haplotype association analysis

We reconstructed haplotypes on the basis of haplotype block structure in each ethnic group. As shown in Supplementary Table S1 online, haplotypes with all major alleles, that is, all 0, occurs most frequently among the participants. Apart from the haplotype with all the major alleles of four SNPs in Block 1 (rs1486004(C/T)-rs7017115(A/G)-rs1843560(C/G)-rs2200477(C/G)), 1-1-1-1 is the next most frequent among whites (29.6%), African Americans (41.1%), Hispanic Americans (35.5%), and Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders (13.4) in Block 1. In Block 2 (rs2290201(C/T)-rs8192688(C/T)-rs2305319(A/G)), apart from the haplotype with all major alleles, only 1-0-0 had frequency larger than 5%. In Block 3 (rs7835371(A/T)-rs3824088(A/G)), 1-1 is the next most frequent among whites (9.2%), African Americans (21.2%), Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders (52.2%), and Hispanics (17.2%). There was statistical evidence showing frequency difference of haplotype in Block 1 (0-0-0-0 and 1-1-1-1), Block 2 (0-0-0 and 1-0-0), and Block 3 (0-0 and 1-1) between ethnic groups (P < 0.05). Such ethnic differences still showed statistical significance after adjusting for multiple testing.

We used 11 SNPs to deduce the common haplotype within each block with a frequency of ≥5% in the combined data of all controls, in spite of ethnicity. As shown in Table 3, we observed two common haplotypes in Block 1, three common haplotypes in Block 2, and three common haplotypes in Block 3. We first performed global tests to find differences in the overall haplotype frequency between cases and controls among each ethnic group and did not observe statistically significant haplotype effects in all blocks. The haplotypes in the table did not appear to be significantly associated with T2D disease risk. There was also no statistically significant interaction between different ethnic groups.

Table 3.

Haplotype-based associations between FABP4 common haplotypes and T2D risk

| Haplotype specific OR(95% CI)a,b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype | White (947/952) | Black (366/751) | Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders (76/165) | Hispanic (140/279) | Pooled (1,529/2,147) | P value for ethnic interaction |

| Block 1 | ||||||

| rs1486004(C/T)-rs7017115(A/G)-rs1843560(C/G)-rs2200477(C/G) | ||||||

| 0-0-0-0 | 1.04 (0.85–1.27) | 1.21 (0.96–1.53) | 0.77 (0.42–1.41) | 1.13 (0.79–1.62) | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 0.61 |

| 1-1-1-1 | 1.01 (0.82–1.24) | 1.07 (0.86–1.33) | 1.09 (0.55–2.17) | 0.85 (0.58–1.24) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | 0.61 |

| P values for global testing | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 0.53 | ||

| Block 2 | ||||||

| rs2290201(C/T)-rs8192688(C/T)-rs12305319(A/G) | ||||||

| 0-0-0 | 1.05 (0.86–1.29) | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 0.76 (0.47–1.21) | 1.04 (0.73–1.48) | 0.99 (0.87–1.13) | 0.84 |

| 1-0-0 | 0.90 (0.66–1.22) | 1.02 (0.83–1.25) | 1.18 (0.76–1.83) | 1.18 (0.77–1.81) | 1.04 (0.90–1.20) | 0.65 |

| 1-1-1 | 0.98 (0.76–1.26) | 1.16 (0.81–1.67) | — b | 0.79 (0.43–1.45) | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) | 0.54 |

| P values for global testing | 0.54 | 0.89 | 0.37 | 0.80 | ||

| Block 3 | ||||||

| rs7835371(A/T)-rs3824088(A/G) | ||||||

| 0-0 | 0.96 (0.75–1.23) | 0.98 (0.78–1.22) | 0.77 (0.48–1.23) | 1.17 (0.75–1.83) | 0.96 (0.83–1.11) | 0.86 |

| 1-1 | 1.07 (0.77–1.49) | 1.06 (0.82–1.38) | 1.29 (0.77–2.15) | 1.20 (0.70–2.06) | 1.11 (0.93–1.32) | 0.89 |

| 1-0 | 1.01 (0.70–1.47) | 0.92 (0.62–1.38) | 1.12 (0.56–2.22) | 0.58 (0.30–1.10) | 0.91 (0.73–1.15) | 0.36 |

| P values for global testing | 0.45 | 0.95 | 0.23 | 0.15 | ||

Odds ratios are estimated using conditional logistic regression adjusted for age, clinical center, time of blood draw, and other confounders, including HRT use, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, BMI, and physical activity.

Result is difficult to interpret because of small sample within strata.

We also assessed the associations between ethnicity-specific haplotypes of the gene and T2D risk. As shown in Supplementary Table S2 online, all odds ratios were not statistically significant among each ethnic group, with the exception of a marginally decreased T2D risk of the 1-0 haplotype (odds ratio: 0.53, 95% confidence interval: 0.27–1.06, P = 0.07). This exception was observed for all carriers vs. all others in Block 3 (rs7835371(A/T)-rs3824088(A/G)) among Hispanics Americans. Matching-adjusted models were also analyzed, and the results were similar to the models adjusted for other covariates, as shown in the Supplementary Table S2 online.

In addition to the previous analyses, the sliding window (with window width = 3 SNPs) was used to analyze haplotype–disease associations. The 11 SNPs generated a total of 9 window frames. No significant association was found between the haplotypes and T2D risk.

Serum biomarkers

We also analyzed the genotype associations with inflammatory and endothelial biomarkers (including TNF-α receptor 2, IL-6, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) and endothelial adhesion molecules (including E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1). With the exception of VCAM-1, none of the inflammatory and endothelial biomarkers showed consistently significant associations. Tables 4–6 show the geometric mean differences in VCAM-1 levels according to the FABP4 genotype in each ethnic group for cases and controls separately. After controlling for the covariates (age, clinical center, time of blood draw, ethnicity, and other confounders, including hormone replacement therapy use, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, BMI, physical activity), we studied the genetic and lifestyle predictors of T2D.

Table 4.

Geometric mean differencesa in Vascular cell adhesion molecule levels according to tagged SNPs and ethnicity among cases

| SNP | Mean difference (s.e.) | P for trend | Mean difference (s.e.) | P for trendb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 947) | Black (n = 366) | |||

| rs1486004 | 1.03 (1.02) | 0.15 | –1.08 (1.03) | 0.01 |

| rs7017115 | 1.02 (1.02) | 0.38 | –1.07 (1.03) | 0.03 |

| rs1843560 | 1.02(1.02) | 0.35 | –1.07 (1.03) | 0.05 |

| rs2200477 | 1.02 (1.02) | 0.29 | –1.09 (1.04) | 0.02 |

| T87C | –1.04 (1.05) | 0.46 | 1.20 (1.26) | 0.43 |

| rs2290201 | 1.01 (1.02) | 0.76 | –1.12 (1.04) | 0.002* |

| rs8192688 | 1.01 (1.02) | 0.55 | 1.00 (1.06) | 0.95 |

| rs2305319 | 1.01 (1.02) | 0.76 | –1.04 (1.05) | 0.41 |

| rs1054135 | 1.01 (1.03) | 0.87 | 1.01(1.04) | 0.76 |

| rs7835371 | –1.02 (1.02) | 0.37 | 1.01 (1.04) | 0.84 |

| rs3824088 | –1.00 (1.03) | 0.99 | –1.05 (1.04) | 0.23 |

| Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders (n = 76) | Hispanic (n = 140) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1486004 | –1.15 (1.09) | 0.09 | 1.01 (1.06) | 0.80 |

| rs7017115 | –1.08 (1.08) | 0.34 | –1.04 (1.06) | 0.48 |

| rs1843560 | –1.09 (1.08) | 0.31 | –1.02 (1.06) | 0.77 |

| rs2200477 | –1.06 (1.08) | 0.43 | 1.02 (1.05) | 0.64 |

| T87C | — c | –1.45 (1.50) | 0.37 | |

| rs2290201 | 1.03 (1.06) | 0.67 | 1.01 (1.06) | 0.80 |

| rs8192688 | — c | –1.04 (1.10) | 0.66 | |

| rs2305319 | –1.10 (1.14) | 0.49 | 1.04 (1.08) | 0.62 |

| rs1054135 | –1.04 (1.09) | 0.61 | 1.07 (1.11) | 0.50 |

| rs7835371 | 1.04 (1.06) | 0.48 | 1.01 (1.07) | 0.84 |

| rs3824088 | 1.07 (1.06) | 0.23 | –1.02 (1.10) | 0.82 |

Geometric mean difference (s.e.) for each SNP was calculated using general linear regression models with adjustment for matching factors (age, clinical center, and time of blood draw) and other confounders, including cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, hormone replacement therapy, and physical activity. Negative sign indicates decreasing level of plasma VCAM-1 with additional copy of risk allele in the corresponding SNP.

Adjusted P value = 0.02 after FDR.

Result is difficult to interpret because of small sample within strata.

Table 6.

Geometric mean differences in VCAM levels according to specific haplotype among black cases (n = 417)

| Haplotype specific geometric mean difference (95% CI)b |

||

|---|---|---|

| Haplotypea | Mean differenceb,c | P for trend |

| rs1486004(C/T)-rs7017115(A/G)-rs1843560(C/G)-rs2200477(C/G) | ||

| 0-0-0-0 | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | 0.01* |

| 0-0-0-1 | –1.02 (–1.20 to –0.87) | 0.78 |

| 1-0-0-1 | –1.00 (–1.11 to –0.90) | 0.95 |

| 1-0-1-1 | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 0.97 |

| 1-1-1-1 | –1.08 (–1.15 to –1.02) | 0.01* |

Haplotype observed with ≥ 0.05 frequency in this ethnic group (0 = major allele, 1 = minor allele).

Geometric mean difference (95% CI) for each SNP was calculated using general linear regression models with adjustment for matching factors (age, clinical center, and time of blood draw) and other confounders, including cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, hormone replacement therapy, and physical activity.

Negative sign indicates decreasing level of plasma VCAM-1 in the corresponding haplotype.

Adjusted P value < 0.05 after FDR.

Among incident cases of the African-American group, plasma VCAM-1 level were −1.08 ng/ml (s.e. = 1.03 ng/ml, P = 0.01) lower in subjects with SNP rs1486004 T allele, −1.07 ng/ml (s.e. = 1.03 ng/ml, P = 0.03) lower in subjects with rs7017115 G allele, −1.07 ng/ml (s.e. = 1.03 ng/ml, P = 0.05) lower in subjects with rs1843560 G allele, −1.09 ng/ml (s.e. = 1.04 ng/ml, P = 0.02) lower in subjects with rs2200477 G allele, and −1.12 ng/ml (s.e. = 1.04 ng/ml, P = 0.002) lower in subjects with rs2290201 T allele. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, rs2290201 still showed a significant decreasing trend in the geometric mean differences of plasma VCAM-1 level (adjusted P = 0.02). Among African-American controls, plasma VCAM-1 level were −1.05 ng/ml (s.e. = 1.02 ng/ml, P = 0.02) in SNP rs2200477. However, this decreasing trend was no longer significant after adjusting for multiple testing (Table 5). The interaction between SNP and VCAM-1 levels was significant (P < 0.05) for both cases and controls, even after multiple testing adjustment.

Table 5.

Geometric mean differencesa in vascular cell adhesion molecule levels according to tagged SNPs and ethnicity among controls

| SNP | mean difference (s.e.) | P for trend | Mean difference (s.e.) | P for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 952) | Black (n = 751) | |||

| rs1486004 | 1.01 (1.02) | 0.54 | –1.03 (1.02) | 0.10 |

| rs7017115 | 1.00 (1.02) | 0.83 | –1.01 (1.02) | 0.55 |

| rs1843560 | 1.01 (1.02) | 0.75 | –1.03 (1.02) | 0.11 |

| rs2200477 | 1.02 (1.02) | 0.18 | –1.05 (1.02) | 0.02b |

| T87C | –1.02 (1.05) | 0.68 | 1.02 (1.12) | 0.89 |

| rs2290201 | 1.01 (1.02) | 0.42 | 1.00 (1.02) | 0.91 |

| rs8192688 | –1.01 (1.02) | 0.78 | –1.01 (1.04) | 0.81 |

| rs2305319 | –1.00 (1.02) | 0.83 | –1.01 (1.03) | 0.81 |

| rs1054135 | 1.06 (1.03) | 0.07 | 1.02 (1.02) | 0.36 |

| rs7835371 | 1.02 (1.02) | 0.41 | 1.03 (1.02) | 0.19 |

| rs3824088 | 1.01 (1.03) | 0.62 | 1.02 (1.03) | 0.38 |

| Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders (n = 165) | Hispanic (n = 279) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1486004 | –1.01 (1.06) | 0.90 | –1.02 (1.04) | 0.55 |

| rs7017115 | –1.02 (1.06) | 0.70 | –1.02 (1.04) | 0.56 |

| rs1843560 | –1.05 (1.06) | 0.34 | –1.01 (1.04) | 0.74 |

| rs2200477 | –1.01 (1.06) | 0.88 | –1.02 (1.04) | 0.66 |

| T87C | — c | –1.20 (1.23) | 0.37 | |

| rs2290201 | 1.00 (1.04) | 0.93 | 1.05 (1.04) | 0.17 |

| rs8192688 | –1.38 (1.39) | 0.33 | 1.01 (1.06) | 0.80 |

| rs2305319 | –1.03 (1.08) | 0.72 | 1.01 (1.05) | 0.87 |

| rs1054135 | 1.02 (1.07) | 0.72 | 1.03 (1.06) | 0.65 |

| rs7835371 | 1.02 (1.04) | 0.67 | 1.07 (1.04) | 0.10 |

| rs3824088 | –1.00 (1.04) | 0.90 | 1.07 (1.05) | 0.15 |

Geometric mean difference (s.e.) for each SNP was calculated using general linear regression models with adjustment for matching factors (age, clinical center, and time of blood draw) and other confounders, including cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, hormone replacement therapy, and physical activity. Negative sign indicates decreasing level of plasma VCAM-1 with additional copy of risk allele in the corresponding SNP.

Adjusted P value = 0.23 after FDR.

Result is difficult to interpret because of small sample within strata.

Data from Tables 4 and 5 showed that only four SNPs in Block 1 (rs1486004(C/T)-rs7017115(A/G)-rs1843560(C/G)-rs2200477(C/G)) were significantly associated with lower VCAM-1 levels among African-American women. We further performed a haplotype–VCAM-1 association analysis in this group (Table 6). The plasma VCAM-1 level was elevated by 1.09 ng/ml (s.e. = 1.04 ng/ml, P = 0.01) in haplotype 0-0-0-0, and the level was lowered by −1.08 ng/ml (s.e. = 1.03 ng/ml, P = 0.01) in haplotype 1-1-1-1. After adjusting for multiple testing, both trends remained significant (adjusted P = 0.04).

DISCUSSION

Based on association tests in 1,529 T2D cases and 2,147 matched controls from a multiethnic cohort of American post-menopausal women, there were little evidence supporting the influence of the FABP4 gene on T2D risk. None of the geno-typed SNPs located near/within the FABP4 gene showed any significant association with T2D. Further, our haplotype-based analyses, as well as sliding-window haplotype analysis did not reveal any significant findings. These null results were consistent across different ethnic groups, including whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders, which results strongly suggest that common genetic variants in FABP4 may not confer a susceptibility to T2D.

The SNPs genotyped in our study covered 7-kbp upstream and 29-kbp downstream region around the FABP4 gene. We may not have enough coverage to detect functional variants around the FABP4 genomic region. We selected the common variant on the basis of available genetic information, and we may not be able to identify potentially function variants, especially rare variants with relatively low frequencies (<5%) that were also not in high LD with any chosen in our study. Sample sizes were relatively small in Hispanic Americans and Asian American/Asian Pacific Islanders , which may not afford sufficient power to detect any moderate association for the FABP4 variants and T2D risk (27,28).

In addition to T2D, the variants in FABP4 have been associated with diseases (obesity (1,7,29), atherosclerosis, (3,9) and cardiovascular disorders (30)) that share some metabolic traits (e.g., insulin resistance) and molecular pathways (e.g., inflammatory activity and macrophage cholesterol trafficking) that also lead to T2D (1,2). Biological data, mainly from animal models, highlight adipocyte P2 in several key pathways in the pathogenesis of T2D, such as lipolytic response, lipolysis-associated insulin secretion (10,11), plasma glucose and insulin level (12), and cytokine secretion (2). Nevertheless, we should interpret these results cautiously because different cell types, experimental conditions, and quantitative methods were adopted in previous studies. The human FABP4 gene, located on chromosome 8q21, encodes a 131 amino-acid precursor protein, including at least two different isoforms regarding alternative translation or splicing processes (31). It is possible that specific FABP4 protein isoform may function as a tissue-specific metabolic modulator.

In the literature, most studies regarding the association between FABP4 and T2D in humans have focused on the serum AFABP rather than its genotype. FABP4 plasma concentrations were reported to be increased with the early presence of metabolic syndrome (MS) components, inflammation, as well as oxidation markers in Spanish and white T2D individuals (6,32). Serum AFABP has also been found to be associated with glucose dysregulation and predictive of T2D development in a Chinese cohort study (24). One study reported a promoter polymorphism, T87C, of the AFABP gene. It reduced adipose tissue AFABP mRNA expression and was associated with lower risk for T2D and cardiovascular disease (25). However, limited investigation has been done on the direct association of the FABP4 gene with T2D. Our findings on T87C were not consistent with previous studies (25). This is likely due to limited sample size, especially after stratifying according to ethnic group. Our large multiethnic case–control study of postmenopausal women showed some suggestive evidence for the relation of the FABP4 genotype and an intermediate phenotype, such as VCAM-1 levels. Endothelial activation, as indicated by elevated levels of soluble adhesion molecules, has been associated with T2D (33). In a prospective analysis with the same source population, high circulating levels of endothelial biomarkers, including VCAM-1, were significantly associated with risk of T2D (14). In the present study, we found that T2D cases with polymorphisms at SNPs (rs1486004, rs7017115, rs1843560, rs2200477, and rs2290201) showed significantly lower VCAM-1 levels among African Americans alone. Consistent results were also shown in the haplotype analysis. The polymorphism at SNP rs2200477 showed significantly lower VCAM-1 level among African-American controls as well. However, because the SNPs are intronic SNPs, it is likely that they are in LD with the nearby causal SNPs and also may simply represent false-positive associations because of multiple testing. Most P values for significant SNP and haplotype associations were above 5% after performing a false-discovery rate for multiple testing. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings (27).

Our study demonstrated substantial heterogeneity in the frequencies of both the alleles and haplotypes in the FABP4 gene among different ethnic groups. Participants from different geographic locations might have different T2D risk, mainly due to their different environmental exposures or different genetic background. Ethnicity may contribute to the FABP4 genetic variants, affecting T2D risk differently. Thus, it has been suggested that population stratification may lead to false-positive results (17,34). We have cautiously selected the control women to be representative of the WHI-OS source population. We have also conducted stratified analyses on the basis of ethnicity, in order to address the potential bias from population stratification. However, at the same time, these ethnicity- stratified analyses lack the power to detect potential associations for the FABP4 SNPs and haplotypes with T2D. Due to the comprehensive screening of SNPs, this may be the first study to determine the haplotype structure of FABP4.

We performed our comprehensive association analyses of informative SNPs (MAF ≥5%), as well as haplotypes based on the LD patterns in each ethnic group constructed from the HapMap database. The analyses provided powerful evidence against a main-effect association between the overall risk of T2D and variants in FABP4 that are common among the four ethnic groups, although the lack of association between FABP4 variants and T2D may also be due to insufficient power and inability to detect changes in phenotypes. If the effect size of each FABP4 variant or haplotype is modest, it would require very large samples to achieve sufficient power for detection. Further studies, like large-scale association and genome-wide association studies, will be necessary to confirm the null association between genetic variants of FABP4 and T2D risk and examine the potential effect modification from biomarkers.

The strengths of our study include the well-established T2D incidence ascertainment methods, which employed standard protocols to define cases and controls following the principle of risk-set sampling; excluded all the prevalent cases from the original case–control sampling set; and matched each case–control pair on age, ethnicity, clinical center, time of blood draw, as well as follow-up time. Finally, our findings may be generalizable to women of similar age and ethnically diverse background because our study included ethnically diverse women from 40 states in the United States.

In conclusion, our large, multiethnic, case–control study of postmenopausal women did not provide evidence to support the notion that common genetic variants in FABP4 may contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of T2D. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of a modest genetic effect as well as genotype–phenotype association. There is some suggestive evidence for an association between the FABP4 geno-types and VCAM-1 levels in African-American women alone, although further replication studies are warranted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services through contracts N01WH2210, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221. This ancillary study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) R01 grant DK062290 from the National Institutes of Health. Y.S. is supported by a grant (K01-DK078846) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institutes of Health. We would like to acknowledge all WHI centers and their principal investigators for their participation in this study. We are indebted to all dedicated and committed participants of the WHIOs. A list of WHI investigators is available in Supplementary Appendix online.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/oby

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Furuhashi M, Hotamisligil GS. Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:489–503. doi: 10.1038/nrd2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makowski L, Brittingham KC, Reynolds JM, Suttles J, Hotamisligil GS. The fatty acid-binding protein, aP2, coordinates macrophage cholesterol trafficking and inflammatory activity. Macrophage expression of aP2 impacts peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and IkappaB kinase activities. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12888–12895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makowski L, Hotamisligil GS. The role of fatty acid binding proteins in metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:543–548. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000180166.08196.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapsys NM, Kriketos AD, Lim-Fraser M, et al. Expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism correlate with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression in human skeletal muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4293–4297. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boord JB, Fazio S, Linton MF. Cytoplasmic fatty acid-binding proteins: emerging roles in metabolism and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:141–147. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabré A, Lázaro I, Girona J, et al. Fatty acid binding protein 4 is increased in metabolic syndrome and with thiazolidinedione treatment in diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:e150–e158. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda K, Cao H, Kono K, et al. Adipocyte/macrophage fatty acid binding proteins control integrated metabolic responses in obesity and diabetes. Cell Metab. 2005;1:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ordovas JM. Identification of a functional polymorphism at the adipose fatty acid binding protein gene (FABP4) and demonstration of its association with cardiovascular disease: a path to follow. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:130–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeung DC, Xu A, Cheung CW, et al. Serum adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein levels were independently associated with carotid atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1796–1802. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.146274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotamisligil GS, Johnson RS, Distel RJ, et al. Uncoupling of obesity from insulin resistance through a targeted mutation in aP2, the adipocyte fatty acid binding protein. Science. 1996;274:1377–1379. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheja L, Makowski L, Uysal KT, et al. Altered insulin secretion associated with reduced lipolytic efficiency in aP2-/- mice. Diabetes. 1999;48:1987–1994. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.10.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uysal KT, Scheja L, Wiesbrock SM, Bonner-Weir S, Hotamisligil GS. Improved glucose and lipid metabolism in genetically obese mice lacking aP2. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3388–3396. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.9.7637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Tinker L, Song Y, et al. A prospective study of inflammatory cytokines and diabetes mellitus in a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1676–1685. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song Y, Manson JE, Tinker L, et al. Circulating levels of endothelial adhesion molecules and risk of diabetes in an ethnically diverse cohort of women. Diabetes. 2007;56:1898–1904. doi: 10.2337/db07-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Women's Health Initiative Study Group Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson GL, Manson J, Wallace R, et al. Implementation of the Women's Health Initiative study design. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S5–17. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu YH, Niu T, Song Y, et al. Genetic variants in the UCP2-UCP3 gene cluster and risk of diabetes in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Diabetes. 2008;57:1101–1107. doi: 10.2337/db07-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Liu S, Niu T, Xu X. SNPHunter: a bioinformatic software for single nucleotide polymorphism data acquisition and management. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CC, You NC, Song Y, et al. Relation of genetic variation in the gene coding for C-reactive protein with its plasma protein concentrations: findings from the Women's Health Initiative Observational Cohort. Clin Chem. 2009;55:351–360. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.117176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe'er I, et al. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/ng1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tso AW, Xu A, Sham PC, et al. Serum adipocyte fatty acid binding protein as a new biomarker predicting the development of type 2 diabetes: a 10-year prospective study in a Chinese cohort. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2667–2672. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuncman G, Erbay E, Hom X, et al. A genetic variant at the fatty acid-binding protein aP2 locus reduces the risk for hypertriglyceridemia, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6970–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602178103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song Y, You NC, Hsu YH, et al. Common genetic variation in calpain-10 gene (CAPN10) and diabetes risk in a multi-ethnic cohort of American postmenopausal women. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2960–2971. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song Y, Hsu YH, Niu T, et al. Common genetic variants of the ion channel transient receptor potential membrane melastatin 6 and 7 (TRPM6 and TRPM7), magnesium intake, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1111–1119. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu A, Wang Y, Xu JY, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein is a plasma biomarker closely associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Clin Chem. 2006;52:405–413. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.062463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prinsen CF, de Bruijn DR, Merkx GF, Veerkamp JH. Assignment of the human adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein gene (FABP4) to chromosome 8q21 using somatic cell hybrid and fluorescence in situ hybridization techniques. Genomics. 1997;40:207–209. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stejskal D, Karpisek M. Adipocyte fatty acid binding protein in a Caucasian population: a new marker of metabolic syndrome? Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:621–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boulbou MS, Koukoulis GN, Makri ED, et al. Circulating adhesion molecules levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2005;98:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lander ES, Schork NJ. Genetic dissection of complex traits. Science. 1994;265:2037–2048. doi: 10.1126/science.8091226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.