Abstract

The ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE) is associated with increased risk and earlier age at onset in late onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Other factors, such as expression level of apolipoprotein E protein (apoE), have been postulated to modify the APOE related risk of developing AD. Multiple loci in and outside of APOE are associated with a high risk of AD. The aim of this exploratory hypothesis generating investigation was to determine if some of these loci predict cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) apoE levels in healthy non-demented subjects. CSF apoE levels were measured from healthy non-demented subjects 21–87 years of age (n = 134). Backward regression models were used to evaluate the influence of 21 SNPs, within and surrounding APOE, on CSF apoE levels while taking into account age, gender, APOE ε4 and correlation between SNPs (linkage disequilibrium). APOE ε4 genotype does not predict CSF apoE levels. Three SNPs within the TOMM40 gene, one APOE promoter SNP and two SNPs within distal APOE enhancer elements (ME1 and BCR) predict CSF apoE levels. Further investigation of the genetic influence of these loci on apoE expression levels in the central nervous system is likely to provide new insight into apoE regulation as well as AD pathogenesis.

Keywords: Apolipoprotein E gene, apolipoprotein E protein, cerebroshinal fluid, enhancer, promoter, SNP

INTRODUCTION

Apolipoprotein E (apoE) is involved in lipid transport and binds to cell surface receptors to mediate lipoprotein uptake. It is the major apolipoprotein synthesized in the brain [23]. The apoE protein exists in three extensively studied isoforms, E2, E3, and E4 that are the result of two non-synonymous SNPs, rs429358 and rs7412, located in exon 4 of the APOE gene. Structural consequences of the exon 4 APOE haplotype appear to be that the apoE E4 protein binds preferentially to plasma very low density lipids (VLDLs) whereas apoE E2 and E3 bind preferentially to plasma high density lipoproteins (HDLs) [13]. In addition, apoE isoforms appear to influence plasma cholesterol levels [5,11], neuronal growth [15,28,41] and amyloid deposition [9, 27,31].

The APOE ε4 allele, defined by the rs429358 SNP, and age are currently the only risk factors strongly associated with late onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [36]. However, a family history of dementia is associated with an increased risk of AD in the elderly only among APOE ε4 carriers and a large proportion of APOE ε4 carriers who survive into old age remain cognitively normal suggesting other genetic factors besides APOE ε4 play a role in AD [12,14].

Cerebrospinal fluid apoE levels

There is no clear consensus on whether cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) apoE levels are associated with AD. Studies thus far indicate CSF apoE is either lower in AD [4, 17,21] or has no association with AD [20,26]. CSF apoE levels in healthy populations appear to be associated with age, but not with gender [16,20,45] although one study did not find an association with age [20]. In addition, APOE ε4 appears not to be associated with CSF apoE levels in healthy populations or AD [4,17, 20,21,26,45], but is associated with lower apoE plasma levels in healthy subjects [21,37]. Interestingly, Fukumoto et al. report that apoE plasma levels are lower in AD compared to the mildly cognitively impaired [10] and APOE e3/e4 heterozygotes have a higher proportion of the apoE E3 isoform than the E4 in plasma [10]. In contrast, the opposite proportion is present in CSF, suggesting a differential metabolism or regulation of apoE isoforms depending on the biological compartment measured; plasma or CSF [10]. Because plasma apoE is produced by the liver and CSF apoE is secreted by brain glial cells [22,33], it appears that apoE and possibly apoE isoforms may be metabolized or regulated differently in the two compartments.

APOE regulatory elements and apoE expression

AD risk has been reported to be associated with APOE promoter polymorphisms directly upstream of the transcription start site. Characterized APOE promoter polymorphisms include −491, −427, −219 (Th1/E47cs), and +113. Establishing AD risk associated with APOE promoter polymorphisms independent of APOE ε4 has been difficult, with contrasting reports likely due to strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) in the region [3,6,30,34,42].

Regulatory sites distal to APOE have been characterized. Multienhancer 1 and 2 (ME1 and ME2) are homologous regulatory regions are located 3.3 and 15.9 kb distal to APOE and influence APOE regulation in macrophages and adipocytes [24,38]. Two homologous hepatic control regions (HCR1 and HCR2) play a role in APOE regulation in the liver and are located approximately 15 kb and 27 kb distal to APOE [1,39]. Recently, a brain control region (BCR) has been described and is located 41.9 kb distal to APOE between APOC2 and CLPTM1 [47].

The influence of APOE promoter SNPs on apoE levels in plasma and brain has been characterized [18] but, to our knowledge, the influence of APOE promoter SNPs and APOE distal regulatory regions on CSF apoE levels has not been investigated.

APOE region and linkage disequilibrium

Several SNPs within the TOMM40 gene, in a region 15 kb proximal to the APOE promoter, are associated with AD risk, but are also in strong LD with APOE ε4 [25,46]. When these SNPs are entered into a logistic regression model that includes APOE ε4, only the effect of APOE ε4 remains significantly associated with AD [46]. These observations diminish the possibility that loci in the TOMM40 gene, proximal to APOE, have a major effect on AD risk independent of APOE ε4. LD with APOE ε4 exists distal to the APOE gene in a region that contains the regulatory element ME1, but is weak in the region of the HCR2 and does not exist in the BCR, suggesting that the ME1 regulatory element is dependent on the presence or absence of APOE ε4, but HCR2 and BCR may be independent of APOE ε4 [46].

Aim of the investigation

Because SNPs upstream of APOE (proximal), as well as SNPs downstream of APOE (distal) within ME1, HCR2 and BCR, are either within a LD block surrounding the APOE gene or are associated with APOE regulation, we hypothesized that genetic elements in the region proximate to APOE along with the APOE promoter and distal regulatory elements (ME1 and BCR), predict apoE expression in CSF, in a manner that can be dependent or independent of APOE ε4. We further hypothesized that HCR2, a hepatic control region of APOE, would not have an effect on the central nervous system and, thus, would not predict CSF apoE levels.

Thus, the aim of this exploratory investigation was to evaluate the potential influence of multiple genetic loci, within and surrounding the APOE gene, on CSF apoE levels in a cognitively normal population. The first aim was to characterize CSF apoE levels according to age, gender and APOE ε4 status in a sample of cognitively normal subjects. The second aim was to explore the influence of the APOE proximal, promoter and distal region SNPs on CSF apoE levels.

METHODS

Subjects

All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. Subjects were 148 healthy carefully evaluated non-demented adults age 21–87 years. All subjects provided written consent. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores were between 26–30 and Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) scores were 0 as previously described [32]. All 148 subjects were genotyped for 22 SNPs within a 70 kb region within and surrounding the APOE gene. Fourteen subjects lacked complete data for all 22 SNPs leaving 134 subjects to be utilized in the analysis. The mean age, gender ratio, APOE ε4 status, and mean CSF apoE levels are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study Subject Characteristics. Age, APOE ε4 status, and mean CSF apoE levels are described for the entire cognitively normal study sample and for males and females

| All | Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | n = 134 | 66 | 68 |

| Age (mean + SD) | 47 ± 19 | 46 ± 20 | 49 ± 18 |

| APOE ε4 Status (% ε4+) | 37 | 38 | 35 |

| Mean CSF ApoE (mg/dl) | 0.376 ± 0.112 | 0.389 ± 0.09 | 0.363 ± 0.129 |

Cerebrospinal fluid

CSF was collected in the morning after an overnight fast using Sprotte 24-g atraumatic spinal needles as previously described [32]. Samples were frozen immediately on dry ice and stored at −80°C until assay at which time apoE concentrations (mg/dl) were measured using a nephelometer (Dade Behring). Nephelometry is an antibody-based automated method that uses the BN II Nephelometer and a kit from Dade Behring for apoE measurement. Briefly, 10 μls of the CSF sample is used undiluted in a reaction between antigen (apoE) and antibody (human anti-apoE). Antibody positive and negative controls are provided with the kit. Nepholometry is a highly standardized method with an average CSF apoE inter-assay variability of less than 1%. No values with an inter-assay variability of greater than 5% are accepted.

Genotyping, DNA sequencing, SNP selection

Genomic DNAs, 5ng each, were dispensed into individual wells of a 384 plate and air dried overnight. Plates were then covered with adhesive lid tape and stored at 4°C. For TaqMan allelic discrimination detection on the 384 well plates, using a final volume of 3 μl per well. For each reaction; 0.075 μl of 20× SNP TaqMan Assay (Applied Biosystems, CA), 1.5 μl of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA) and 1.425 μl of dH2O were pipetted into each well. PCR reactions were carried out using a 9700 Gene Amp PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA). The PCR profile was 95°C for 10 min and then 50 cycles at 92°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 90 sec. Plates were then subjected to end-point read in a 7900 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA). Twenty one SNPs were genotyped including APOE proximal SNPs, APOE promoter SNPs, SNPs within the APOE gene and APOE distal SNPs (Table 3). The results were first evaluated by cluster variations, the allele calls were then assigned automatically before transferred and integrated into the genotype database, except for the ME1 and HCR2 SNPs.

Table 3.

Backward Linear Regression Models. Two backward linear regression models were utilized to evaluate the influence of APOE region SNPs on CSF apoE levels. CSF apoE level for each cognitively normal individual (n = 134) was entered into a backward linear regression model as the dependent variable and SNPs (n = 21); including the SNP representing APOE ε 4 status, age, and gender were entered as the independent variables. SNPs were entered either as genotype (coded as 1, 2 or 3)

| Condition R2 | 0.19 beta (std error) | p-value | Bonferroni Corrected p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs | |||

| rs11556505 | 0.072 (0.031) | 0.020 | 0.142 |

| n17664883 | −0.075 (0.027) | 0.007 | 0.049 |

| rs157584 | 0.055 (0.019) | 0.004 | 0.028 |

| rs449647 | −0.044 (0.018) | 0.016 | 0.113 |

| n17684509 | −0.053 (0.019) | 0.007 | 0.050 |

| rs7247551 | −0.028 (0.013) | 0.035 | 0.242 |

| Covariates | |||

| Age | 0.002 (0.000) | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| Gender | – | – | – |

| APOE ε 4 | – | – | – |

| (Intercept) | 0.400 (0.064) | 0.000 | 0.000 |

The backward regression model p-value does not correct for multiple comparisons. The Bonferroni corrected p-value shows the p-value after.

The ME1 and HCR2 SNPs are located within a duplicated region, which has extremely high homology with ME2 and HCR1 elements, and thus were first PCR amplified (95°C for 15 min, 30 cycles of 92°C for 20 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 15 min) using primer sets specific to the one region surrounding the SNPs (not the duplication) and then subsequently DNA sequenced to determine the nucleotide content at each SNP site. BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, CA) in a final volume of 10 μl, and the sequence information were collected from an 377 DNA Sequencer (AB). Primer sequences for region-specific PCR and sequencing is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

SNPs were selected in the region surrounding the APOE gene. SNPs included SNPs proximate to the APOE gene that have been previously described [46], SNPs distal to APOE, and SNPs within ME1, HCR2 and BCR. All SNPs are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

SNP description. The 21 SNPs investigated are described including; SNP ID, Gene or gene element, gene region, SNP position, allele, and genotype frequency for the study sample (n = 134)

| No | SNP ID | Gene/Element | Region | Position in NT 011109.15 | Allele | Genotype Frequency in CSF Sample All (n = 134) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs6857 | 5′ TOMM40 | 17660472 | G/a | 0.657_0.321_0.022 | |

| 2 | rs184017 | TOMM40 | Intron 2 | 17663187 | A/c | 0.522_0.410_0.067 |

| 3 | rs157580 | TOMM40 | Intron 2 | 17663484 | A/g | 0.440_0.440_0.119 |

| 4 | rs157581 | TOMM40 | Exon 3 | 17663932 | T/c | 0.522_0.403_0.075 |

| 5 | rs11556505 | TOMM40 | Exon 4 | 17664362 | C/t | 0.679_0.291_0.030 |

| 6 | n17664883* | TOMM40 | Intron 4 | 17664883 | C/a | 0.560_0.396_0.045 |

| 7 | rs157584 | TOMM40 | Intron 4 | 17665117 | A/g | 0.313_0.440_0.246 |

| 8 | rs157588 | TOMM40 | Intron 6 | 17666482 | C/t | 0.328_0.433_0.239 |

| 9 | rs741780 | TOMM40 | Intron 8 | 17672649 | A/g | 0.403_0.410_0.187 |

| 10 | rs10119 | TOMM40 | Exon 10 | 17674891 | G/a | 0.500_0.381_0.119 |

| 11 | rs449647 | APOE −491 | 5′UTR | 17676782 | A/t | 0.716_0.254_0.030 |

| 12 | rs769446 | APOE −427 | 5′UTR | 17676846 | T/c | 0.828_0.172_0.000 |

| 13 | rs405509 | APOE −219 | 5′UTR | 17677054 | T/g | 0.276_0.485_0.239 |

| 14 | rs440446 | APOE +113 | Intron 1 | 17677385 | G/c | 0.433_0.418_0.149 |

| 15 | rs769449 | APOE | Intron 2 | 17678220 | G/a | 0.716_0.261_0.022 |

| 16 | rs429358 | APOE ε4 | Exon 4 | 17680159 | T/c | 0.634_0.343_0.022 |

| 17 | rs483082 | ME1 | 17684396 | G/t | 0.522_0.373_0.105 | |

| 18 | n17684509* | ME1 | 17684509 | C/t | 0.455_0.425_0.119 | |

| 19 | rs584007 | ME1 | 17684696 | G/a | 0.433_0.418_0.149 | |

| 20 | rs35136575 | HCR2 | 17707381 | C/g | 0.590_0.336_0.075 | |

| 21 | rs7247551 | BCR | 17722984 | A/g | 0.269_0.508_0.224 |

novel SNPs.

Statistical analysis

We examined the relationship between CSF apoE levels and APOE region SNPs, gender, and age using backward stepwise linear regression models. One SNP (rs157582) was omitted from all analyses because it was perfectly correlated with another SNP (rs157581) leaving 21 SNPs for the analyses. Except for rs429358, SNP genotypes were coded as 1, 2, or 3 and treated as continuous variables. The contribution of the rs429358 SNP was modeled using APOE ε4 status (coded as 1 or 2, where 2 denotes no ε4 alleles are present).

Backward elimination was performed using a variable selection procedure in which all variables are entered into the equation and then sequentially removed until the stopping criterion is reached [8]. The variable with the smallest partial correlation with the dependent variable was considered first for removal. Variables were removed listwise from the model depending on the significance of the partial F-value (p-value > 0.10). After the first variable was removed, the variable remaining in the equation with the smallest partial correlation was considered next. The procedure stopped when there were no variables in the equation that satisfied the removal criteria (p-value > 0.10). R2 values were determined to assess the proportion of variability in CSF apoE levels that is explained by the predictor variables. The backward regression p-values do not take into account multiple comparisons. Bonferroni multiple comparison corrections were performed (Table 3, Table 5). Backwards regression based on the Akaike Information Criterion was also performed with the same results as the backward regression shown in Table 3 (data not shown) [43].

Table 5.

Haplotype mean CSF apoE levels. Mean CSF apoE levels for haploytype combinations of all six SNPs in Table 3 were evaluated taking into account age. Only those haplotypes that predict (p-value ~ 0.05) CSF apoE levels are shown. Only the variant carrier and non-variant carrier haplotype mean values are shown as they have the lowest and highest CSF apoE levels, respectively. The p-value represents the overall significance of all haplotype combinations within the haplotype group shown

| Region | Allele | Haplotype | n= | ApoE Mean | Std. Error | 95% CI | Haplotype p-value * | Bonferroni p-value * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| TOMM40-APOE | n17664883 | rs449647 | ||||||||||

| Variant | CA, AA | AT, TT | 20 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.39 | |||||

| Non-Variant | CC | AA | 57 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.042 | 0.170 | |||

| APOE-ME1 | rs449647 | n17684509 | ||||||||||

| Variant | AT, TT | CT, TT | 12 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.38 | |||||

| Non-Variant | AA | CC | 35 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.057 | 0.228 | |||

| ME1-BCR | n17684509 | rs7247551 | ||||||||||

| Variant | CT, TT | AG, GG | 55 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.40 | |||||

| Non-Variant | CC | AA | 18 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| APOE-ME1-BCR | rs449647 | n17684509 | rs7247551 | |||||||||

| Variant | AT, TT | CT, TT | AG, GG | 7 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.38 | ||||

| Non-Variant | AA | CC | AA | 12 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.023 | 0.185 | ||

| TOMM40-ME1-BCR | n17664883 | n17684509 | rs7247551 | |||||||||

| Variant | CA, AA | CT, TT | AG, GG | 16 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.40 | ||||

| Non-Variant | CC | CC | AA | 6 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.054 | 0.430 | ||

| TOMM40-APOE-ME1-BCR | n17664883 | rs449647 | n17684509 | rs7247551 | ||||||||

| Variant | CA, AA | AT, TT | CT, TT | AG, GG | 3 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.46 | |||

| Non-Variant | CC | AA | CC | AA | 5 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

p-values are for within haplotype comparisons.

RESULTS

APOE ε4 genotype, gender, age and CSF apoE levels

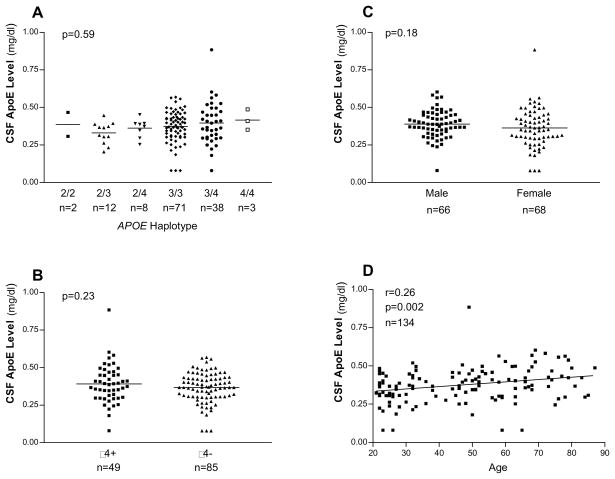

To determine if CSF apoE levels in our study sample (n = 134) are consistent with previous studies in which CSF apoE levels were not found to be associated with APOE ε4 [4,17,20,21,26]or gender but were associated with age [16,20,45], CSF apoE levels were stratified by APOE genotype, the presence or absence APOE ε4, gender and age (Fig. 1). No significant difference in CSF apoE levels between APOE genotypes (p = 0.59 in ε2/ε3/ε4 genotype and p = 0.23 in ε4 allele, Fig. 1, panel A and panel B) and gender (p = 0.18, Fig. 1, panel C) was found. In contrast, a significant increase in CSF apoE levels with increasing age was observed (p = 0.002, Fig. 1, panel D).

Fig. 1. APOE ε4, gender, age and CSF apoE levels.

There is no significant difference in CSF apoE levels between APOE genotypes (Panel A) or between the presence or absence of APOE ε4 (Panel B). There is not a significant difference in CSF apoE levels between genders (Panel C). There is a significant increase in CSF apoE with increasing age (Panel D).

APOE regional SNPs and correlations with APOE ε4

SNPs (Table 2) were selected either on the basis of our previous study that found most of these SNPs to be in LD with APOE ε4 as well as associated with AD risk [46], or on the basis of their position within ME1, HCR2 or BCR. These SNPs (n = 21) span approximately 70 kb and range from a proximal SNP (rs6857) located 5′ of the TOMM40 gene, to a distal SNP (rs7247551) within the APOE BCR.

All SNPs (n = 21) are in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (data not shown). In addition, we determined the LD structure, (utilizing D′ and R2), within this study sample and found it to be similar to our previous findings (Table 4) [46]. These results suggest the presence of LD across the region, which is consistent with our previous observation [46].

Table 4.

Linkage Disequilibrium Surrounding the APOE gene. A 70 kb region from the 5′ proximal region at rs6857 to the 3′ distal region at rs7247551. Measures of linkage disequilibrium including D′ and R2

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs6857 | rs184017 | rs157580 | rs157581 | rsl1556505 | n17664883 | rs157584 | rs157588 | rs741780 | rs10119 | rs449647 | rs769446 | rs405509 | rs440446 | rs769449 | rs429358 | rs483082 | n17684509 | rs584007 | rs35136575 | rs7247551 | |||

| 1 | rs6857 | — | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1 |

| 2 | rs184017 | 1.00 | — | 0.23 | 0.95 | 0.38 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 2 |

| 3 | rs157580 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 3 |

| 4 | rs157581 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 4 |

| 5 | rs11556505 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.71 | 0.95 | — | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 5 |

| 6 | n17664883 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.93 | — | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 6 |

| 7 | rs157584 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.22 | — | 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 7 |

| 8 | rs157588 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.10 | 0.91 | 0.20 | 1.00 | — | 0.66 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 8 |

| 9 | rs741780 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 9 |

| 10 | rs10119 | 0.90 | 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.94 | — | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 10 |

| 11 | rs449647 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.50 | — | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 11 |

| 12 | rs769446 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 1.00 | — | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 12 |

| 13 | rs405509 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.00 | — | 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 13 |

| 14 | rs440446 | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 0.54 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.97 | — | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.69 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 14 |

| 15 | rs769449 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 15 |

| 16 | rs429358 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | 0.49 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 16 |

| 17 | rs483082 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.61 | 0.23 | 0.50 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.96 | — | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 17 |

| 18 | n17684509 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 18 |

| 19 | rs584007 | 0.19 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | 0.18 | 0.00 | 19 |

| 20 | rs35136575 | 0.04 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.58 | — | 0.03 | 20 |

| 21 | rs7247551 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.30 | — | 21 |

| D′ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | ||

APOE region SNPs predict CSF apoE levels

We applied backward regression models to assess the effects of the 21 SNPs on CSF apoE levels (Table 3) while taking into account APOE ε4 status, gender and age. The models show that six SNPs may predict CSF apoE levels, including three SNPs in the proximal region (rs11556506, n17664883, rs157584), one in the promoter (rs449647; −491), and two in the distal region (n17684509; ME1 and rs7247551; BCR) of APOE. The proportion of variance explained by the model, as calculated by R2, is 19%. Backward regression models based on the Akaike Information Criterion gave similar results where the same six SNPs predicted CSF apoE levels (data not shown).

In models in which only age and each of the six SNPs are entered alone, without other SNPs, into a linear regression model, either with or without APOE ε4 present in the model, only rs449647, independent of APOE ε4, and n17664883, in the presence of APOE ε4, predict CSF apoE levels (data not shown).

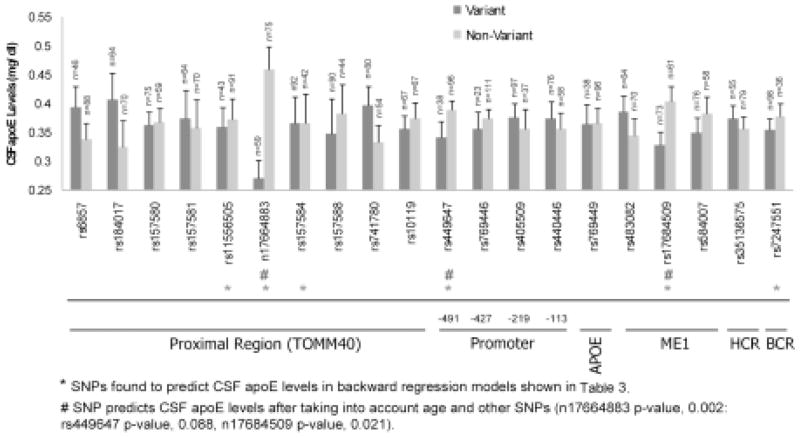

To determine if carriers of the more rare alleles (minor-allele-homozygoteplus heterozygote) have low CSF apoE levels, each SNP was collapsed into “non-variant” group (with major-allele-homozygote only) and “variant” group (with minor-allele-homozygote plus heterozygote) and linear regression was performed while taking into account age but not APOE ε4. In this model n17664883 (p-value, 0.002) and n17684509 (p-value, 0.021) predict CSF apoE levels while rs449647 marginally predicts CSF apoE levels (p-value, 0.088) (Fig. 2). However, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, only n17664883 remains significant (p-value, 0.030). Mean CSF apoE levels for SNP variant carriers compared to non-variant carriers while taking into account age are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. CSF apoE mean levels.

Bars represent CSF apoE means for variant or non-variant carrier groups for each SNP after taking into account age. Error bars represent standard error and n equals the number of individuals within the group analyzed. SNPs found to predict CSF apoE levels in backward regression models shown in Table 3 are designated with a *. SNPs found to predict CSF apoE levels after taking into account age and other SNPs (n17664883 p-value, 0.002: rs449647 p-value, 0.088, n17684509 p-value, 0.021) are designated with a #.

To further address the question of whether a combination of SNPs may contribute to CSF apoE levels the six positive SNPs identified in the backward regression models were analyzed for their ability to predict CSF apoE levels. All possible combinations of these six SNPs were analyzed. Five haplotypes were found to predict CSF apoE levels while taking into account age and while taking into account all the haplotype combinations within the haplotype tested (Table 5: see haplotype p-values). After correcting for multiple comparisons only two of these haplotypes predict CSF apoE levels (see Bonferroni p-values for haplotype: n17684509, rs7247551 and haplotype: n17664883, rs449647, n17684509, rs7247551) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Because APOE ε4 and age are important AD risk factors, the characterization of regulatory elements surrounding the APOE gene that may predict the level of apoE E4 protein, is vital in understanding AD pathogenesis. The influence of APOE promoter SNPs on apoE levels in plasma and brain has been studied [18, 19] but, to our knowledge, the influence of APOE promoter SNPs or APOE distal regulatory regions on CSF apoE levels has not been characterized. In a previous investigation, SNPs proximal to APOE were found to be associated with AD risk [46] leading us to wonder if SNPs in the region proximal to APOE lay within an un-characterized APOE regulatory element. Thus, in this investigation we evaluated the differences in healthy subjects CSF apoE levels while taking into account age, gender and APOE ε4 status, as well as associations with 21 SNPs in a large 70 kb region surrounding the APOE gene. This study was an exploratory investigation to test the hypothesis that multiple genetic loci surrounding APOE can predict CSF apoE levels. The results indicate that in addition to the APOE promoter, SNPs in the TOMM40 gene, the ME1 and the BCR regions may also predict CSF apoE levels.

Consistent with the previous reports, CSF apoE levels increased with increasing age (Fig. 1, Panel D); and the levels were not associated with APOE ε4 genotype (Fig. 1, Panel A) or allele (Fig. 1, Panel B) or gender (Fig. 1, Panel C) [4,16,17,20,21,26,45].

Backward linear regression models indicate that out of the 21 SNPs entered into the models, six SNPs may predict CSF apoE levels (three SNPs within TOMM40; rs11556505, n17664883, rs157584, one APOE promoter SNP, rs449647, one SNP within ME1; n17684509, and one SNP within the BCR; rs7247551; Table 3). Of these six SNPs only two SNPs predict CSF apoE levels either with APOE ε4 (n17664883) or without APOE ε4 (rs449647) present in the model (data not shown).

Interestingly, previous reports indicate that the APOE −491 promoter polymorphism (rs449647) is associated with AD risk, although it is unclear whether LD is obscuring these results [6,30,42]. In our investigation the non-variant (AA genotype) carriers of −491 polymorphism appeared to have higher CSF apoE levels than the variant (AT and TT genotypes) carriers both alone and as part of a haplotype (Fig. 2; Table 5) which is consistent with previous reports by Laws et al. where higher brain apoE levels [18] and plasma apoE levels [19] are associated with the −491 AA genotype. To our knowledge this is the first investigation of the association between CSF apoE levels and APOE promoter SNPs. These results reported here, along with previous reports, implicate the −491 promoter polymorphism as an important regulator of apoE levels.

The association with the novel proximal SNP, n17664883, suggests that an APOE regulatory element exists in the region distantly proximal to APOE that may predict CSF apoE levels. This region within intron 4 of the TOMM40 gene, may contain a regulatory element that contributes to high CSF apoE levels when the major homozygote genotype (non-variant) is present (Fig. 2, Table 5). Whereas the minor homozygote or the heterozygotes (variant) may contribute to lower CSF apoE levels (Fig. 2, Table 5). Alternatively, CSF apoE levels may be consequences of TOMM40 gene action. The TOMM40 gene encodes the TOM40 protein which is the pore subunit of the mitochondrial outer membrane protein translocator [35]. Currently, there is no evidence of protein-protein interaction between TOM40 and apoE. However, recent reports suggest that AβPP may be targeted to the mitochondria and translocated across the mitochondrial membrane via the TOM40 protein [2]; additionally, the translocation arrest of AβPP in the TOM40 pore may lead to mitochondria dysfunction and neuronal loss in AD [7]. Therefore, it is possible that variants of TOM40 may be more susceptible to the translocation arrest of AβPP and may lead to more profound decline of mitochondrial function and neuronal damage. The biological feedback mechanism would then be activated and produce more apoE for the neuronal repair or regeneration, a well-known function of apoE.

We also assessed whether the APOE distal regulatory elements (HCR, ME and BCR) can predict CSF apoE levels. Because evidence suggests that the HCR is primarily active in the liver [1,39], we hypothesized that only the SNPs within the ME1 (rs483082, n17684509, rs584007) and BCR (rs7247551) but not HCR2 (rs35136575), would predict apoE expression in CSF. Indeed, in our analyses the HCR2 SNP did not have an effect on CSF apoE levels, but SNPs from both ME1 and BCR did (Table 3, Fig. 2, Table 5). Interestingly, only one of the three SNPs within ME1, a small region which spans 620 bp, is predicted to be associated with CSF apoE levels (Table 3). This result may be attributed to high correlation of other SNPs in the model with SNPs in the ME1 region, thus, leading to the elimination of other ME1 SNPs from the regression model. This result does not necessarily reflect a lack of a biological influence on CSF apoE levels by the other ME1 SNPs.

The hypothesis generated by these results is that there may be additional regulators of APOE in the proximal region as far upstream as 15 kb. The proximal region may act in combination with regulatory elements in the distal region, such as the ME1 and the BCR to increase the activity of the APOE promoter. An example of distant proximal enhancers can be demonstrated by the APOB gene, which has a cis-element enhancer located 54 to 62 kilobases 5′ to the structural gene [29]. Further support of our hypothesis is demonstrated by our finding whereby multiple loci together have effects on CSF apoE levels (Table 3, Fig. 2, Table 5) implicating an influence on CSF apoE levels by a large haplotype. Such a concept is in line with studies suggesting that promoter haplotypes of APOE can influence plasma apoE levels [40,44]. But, our study goes beyond previous studies by investigating contributions by distal regulatory regions, such as ME1, HCR2 and BCR, on CSF apoE levels.

There were limitations of this exploratory investigation. First, our study sample size (n = 134) may be too small to detect small effects contributed by a few of the SNPs tested that have low minor allele frequencies. Even though we required all minor allele frequencies to be equal to or greater than 2%, and collapsed genotypes into variant and non-variant groups, some of the haplotype numbers were low (Table 5). Second, the statistical results should be approached with caution because stepwise linear regression models do not take into account multiple comparisons so that p-values do not represent true significance until corrected for multiple comparisons (Table 3). Thus, it is important to note that this is an exploratory investigation intended to generate further hypotheses.

In summary, linear regression models were used to search for APOE regulatory SNPs that predict CSF apoE levels. These SNPs are located within a large region surrounding the APOE gene. Six SNPs were found to predict CSF apoE levels; three TOMM40 SNPs (rs11556505, n17664883, rs157584), one APOE promoter SNP (rs449647; −491) and two APOE distal SNPs (ME1; n17684509, BCR; rs7247551). For two of these SNPs, the novel SNP within the TOMM40 gene (n17664883) and the APOE promoter SNP (rs449647; −491), there is a significant difference in CSF apoE levels between genotypes and these two SNPs also appear to contribute to haplotype CSF apoE levels. These results support the hypothesis that modestly penetrant SNPs within APOE regulatory elements may explain part of the variation in CSF apoE protein levels. Our data indicate that a multigenetic approach may be more powerful in explaining the variation in apoE levels than a monogenetic approach. However, the total contribution of several SNPs together was modest, with a large proportion of the variation remaining unaccounted for (R2 value, 0.19; Table 3), which may suggest that future evaluation of molecular haplotypes in the APOE gene region in a larger study population is required to explain more specifically the variation in apoE levels. In addition, given that APOE proximal SNPs within the TOMM40 gene predict CSF apoE levels, a possible independent influence on CSF apoE levels by the TOM40 protein may exist.

The mechanism whereby APOE ε4 increases the risk of AD is uncertain. APOE ε4 carriers show substantial variance for age at onset of AD. Some individuals who are ε4 homozygotes may be spared from AD even if they live into their 9th or 10th decade [12,14]. Factors that alter apoE protein expression, such as an APOE ε4 haplotype that includes proximal and distal regulatory elements, may help to explain this variance. In addition to aging, we have now shown that certain SNPs appear to be associated with levels of apoE protein in CSF in cognitively normal individuals. If these SNPs are also associated with younger age of onset in AD, this would implicate levels of apoE as a factor in AD pathogenesis. An extension of this study would be an investigation of familial AD cases to evaluate the influence of family history of AD on AD age-at-onset and associations between SNPs within and around APOE, APOE ε4 status, CSF apoE levels as well as other AD biomarkers such as CSF Aβ40, Aβ42, and tau.

In conclusion, this exploratory investigation has generated further hypotheses regarding the possible influence on CSF apoE levels by multiple genetic loci within and surrounding the APOE gene suggesting that the actual effect is likely to be determined by these loci’s haplotype structure.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Alzheimer’s Association (IIRG-03-4750), NIA (R21 AG24486-01), Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research Development Merit Review (ID1127558), Ruth L Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NR-SA) (5T32AG000258-07), NINDS (R01 NS48595), VISN20 MIRECC, NIA (AG05136), NIH P01HL30086, Alzheimer’s Center Grant (AG08017), National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, Friends of Alzheimer’s Research, Alzheimer’s Association of Western and Central Washington, an anonymous foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Kaye is on the advisory board of Myriad Pharmaceuticals and receives grant support from the Intel Corporation. Dr. Farlow is a consultant for Abbott Labs, Accera Inc., Adamas Pharm, Cephalon Inc., Comentis, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Medivation, Inc., Memory Pharm, Merck and Co., Neurochem, Novartis, OctaPharma, Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, Shering Plough, Takada Pharmaceuticals, Talecris Biotherapeutics, and Worldwide Clinical Trials. Additionally, Dr. Farlow receives grant support from Ono Pharmanet, Eli Lilly and Co., Wyeth, and Elan Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Quinn is a member of the speaker’s bureau of Pfizer and Forest.

Footnotes

Communicated by Thomas Montine

References

- 1.Allan CM, Walker D, Taylor JM. Evolutionary duplication of a hepatic control region in the human apolipoprotein E gene locus. Identification of a second region that confers high level and liver-specific expression of the human apolipoprotein E gene in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anandatheerthavarada HK, Biswas G, Robin MA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial targeting and a novel transmembrane arrest of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein impairs mitochondrial function in neuronal cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Artiga MJ, Bullido MJ, Sastre I, Recuero M, Garcia MA, Aldudo J, Vazquez J, Valdivieso F. Allelic polymorphisms in the transcriptional regulatory region of apolipoprotein E gene. FEBS Lett. 1998;421:105. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blennow K, Hesse C, Fredman P. Cerebrospinal fluid apolipoprotein E is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport. 1994;5:2534. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boerwinkle E, Utermann G. Simultaneous effects of the apolipoprotein E polymorphism on apolipoprotein E, apolipoprotein B, and cholesterol metabolism. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;42:104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullido MJ, Artiga MJ, Recuero M, Sastre I, Garcia MA, Aldudo J, Lendon C, Han SW, Morris JC, Frank A, Vazquez J, Goate A, Valdivieso F. A polymorphism in the regulatory region of APOE associated with risk for Alzheimer’s dementia. Nat Genet. 1998;18:69. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devi BM, Prabhu, Galati DF, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK. Accumulation of amyloid precursor protein in the mitochondrial import channels of human Alzheimer’s disease brain is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9057. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1469-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Draper NR, Smith H. Applied Regression Analysis. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ezra Y, Oron L, Moskovich L, Roses AD, Beni SM, Shohami E, Michaelson DM. Apolipoprotein E4 decreases whereas apolipoprotein E3 increases the level of secreted amyloid precursor protein after closed head injury. Neuroscience. 2003;121:315. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukumoto H, Ingelsson M, Garevik N, Wahlund LO, Nukina N, Yaguchi Y, Shibata M, Hyman BT, Rebeck GW, Irizarry MC. APOE epsilon 3/epsilon 4 heterozygotes have an elevated proportion of apolipoprotein E4 in cerebrospinal fluid relative to plasma, independent of Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Exp Neurol. 2003;183:249. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gronroos P, Raitakari OT, Kahonen M, Hutri-Kahonen N, Marniemi J, Viikari J, Lehtimaki T. Influence of apolipoprotein E polymorphism on serum lipid and lipoprotein changes: a 21-year follow-up study from childhood to adulthood. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:592. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang W, Qiu C, von Strauss E, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. APOE genotype, family history of dementia, and Alzheimer disease risk: a 6-year follow-up study. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1930. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.12.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Weisgraber KH, Mucke L, Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E: diversity of cellular origins, structural and biophysical properties, and effects in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;23:189. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:3:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyman BT, Gomez-Isla T, Rebeck GW, Briggs M, Chung H, West HL, Greenberg S, Mui S, Nichols S, Wallace R, Growdon JH. Epidemiological, clinical, and neuropathological study of apolipoprotein E genotype in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;802:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb32592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji Y, Gong Y, Gan W, Beach T, Holtzman DM, Wisniewski T. Apolipoprotein E isoform-specific regulation of dendritic spine morphology in apolipoprotein E transgenic mice and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neuroscience. 2003;122:305. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunicki S, Richardson J, Mehta PD, Kim KS, Zorychta E. The effects of age, apolipoprotein E phenotype and gender on the concentration of amyloid-beta (A beta) 40, A beta 4242, apolipoprotein E and transthyretin in human cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Biochem. 1998;31:409. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(98)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landen M, Hesse C, Fredman P, Regland B, Wallin A, Blennow K. Apolipoprotein E in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia is reduced but without any correlation to the apoE4 isoform. Dementia. 1995;7:273. doi: 10.1159/000106892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laws SM, Hone E, Taddei K, Harper C, Dean B, Mc-Clean C, Masters C, Lautenschlager N, Gandy SE, Martins RN. Variation at the APOE −491 promoter locus is associated with altered brain levels of apolipoprotein E. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:886. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laws SM, Taddei K, Martins G, Paton A, Fisher C, Clarnette R, Hallmayer J, Brooks WS, Gandy SE, Martins RN. The −491AA polymorphism in the APOE gene is associated with increased plasma apoE levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport. 1999;10:879. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199903170-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefranc D, Vermersch P, Dallongeville J, Daems-Monpeurt C, Petit H, Delacourte A. Relevance of the quantification of apolipoprotein E in the cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1996;212:91. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12774-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehtimaki T, Pirttila T, Mehta PD, Wisniewski HM, Frey H, Nikkari T. Apolipoprotein E (apoE) polymorphism and its influence on ApoE concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid in Finnish patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Genet. 1995;95:39. doi: 10.1007/BF00225071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linton MF, Gish R, Hubl ST, Butler E, Esquivel C, Bry WI, Boyles JK, Wardell MR, Young SG. Phenotypes of apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein E after liver transplantation. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:270. doi: 10.1172/JCI115288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E4: a causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600549103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mak PA, Laffitte BA, Desrumaux C, Joseph SB, Curtiss LK, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P, Edwards PA. Regulated expression of the apolipoprotein E/C-I/C-IV/C-II gene cluster in murine and human macrophages. A critical role for nuclear liver X receptors alpha and beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin ER, Lai EH, Gilbert JR, Rogala AR, Afshari AJ, Riley J, Finch KL, Stevens JF, Livak KJ, Slotterbeck BD, Slifer SH, Warren LL, Conneally PM, Schmechel DE, Purvis I, Pericak-Vance MA, Roses AD, Vance JM. SNPing away at complex diseases: analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms around APOE in Alzheimer disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:383. doi: 10.1086/303003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulder M, Ravid R, Swaab DF, de Kloet ER, Haasdijk ED, Julk J, van der Boom JJ, Havekes LM. Reduced levels of cholesterol, phospholipids, and fatty acids in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer disease patients are not related to apolipoprotein E4. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1998;12:198. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199809000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myllykangas L, Polvikoski T, Reunanen K, Wavrant-De Vrieze F, Ellis C, Hernandez D, Sulkava R, Kontula K, Verkkoniemi A, Notkola IL, Hardy J, Perez-Tur J, Haltia MJ, Tienari PJ. ApoE epsilon3-haplotype modulates Alzheimer beta-amyloid deposition in the brain. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:288. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nathan BP, Jiang Y, Wong GK, Shen F, Brewer GJ, Struble RG. Apolipoprotein E4 inhibits, and apolipoprotein E3 promotes neurite outgrowth in cultured adult mouse cortical neurons through the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Brain Res. 2002;928:96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen LB, Kahn D, Duell T, Weier HU, Taylor S, Young SG. Apolipoprotein B gene expression in a series of human apolipoprotein B transgenic mice generated with recA-assisted restriction endonuclease cleavage-modified bacterial artificial chromosomes. An intestine-specific enhancer element is located between 54 and 62 kilobases 5′ to the structural gene. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker GR, Cathcart HM, Huang R, Lanham IS, Corder EH, Poduslo SE. Apolipoprotein gene E4 allele promoter polymorphisms as risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatr Genet. 2005;15:271. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200512000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Permanne B, Perez C, Soto C, Frangione B, Wisniewski T. Detection of apolipoprotein E/dimeric soluble amyloid beta complexes in Alzheimer’s disease brain supernatants. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:715. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peskind ER, Li G, Shofer J, Quinn JF, Kaye JA, Clark CM, Farlow MR, DeCarli C, Raskind MA, Schellenberg GD, Lee VM, Galasko DR. Age and apolipoprotein E*4 allele effects on cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42 in adults with normal cognition. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:936. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitas RE, Boyles JK, Lee SH, Foss D, Mahley RW. Astrocytes synthesize apolipoprotein E and metabolize apolipoprotein E-containing lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;917:148. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(87)90295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos MC, Matias S, Artiga MJ, Pozueta J, Sastre I, Valdivieso F, Bullido MJ. Neuronal specific regulatory elements in apolipoprotein E gene proximal promoter. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1027. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200506210-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapaport D. How does the TOM complex mediate insertion of precursor proteins into the mitochondrial outer membrane? J Cell Biol. 2005;171:419. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schellenberg GD, D’Souza I, Poorkaj P. The genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2:158. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0061-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiele F, De Bacquer D, Vincent-Viry M, Beisiegel U, Ehnholm C, Evans A, Kafatos A, Martins MC, Sans S, Sass C, Visvikis S, De Backer G, Siest G. Apolipoprotein E serum concentration and polymorphism in six European countries: the ApoEurope Project. Atherosclerosis. 2000;152:475. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shih SJ, Allan C, Grehan S, Tse E, Moran C, Taylor JM. Duplicated downstream enhancers control expression of the human apolipoprotein E gene in macrophages and adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005468200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simonet WS, Bucay N, Lauer SJ, Taylor JM. A far-downstream hepatocyte-specific control region directs expression of the linked human apolipoprotein E and C-I genes in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stengard JH, Clark AG, Weiss KM, Kardia S, Nickerson DA, Salomaa V, Ehnholm C, Boerwinkle E, Sing CF. Contributions of 18 additional DNA sequence variations in the gene encoding apolipoprotein E to explaining variation in quantitative measures of lipid metabolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:501. doi: 10.1086/342217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teter B, Xu PT, Gilbert JR, Roses AD, Galasko D, Cole GM. Defective neuronal sprouting by human apolipoprotein E4 is a gain-of-negative function. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68:331. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Town T, Paris D, Fallin D, Duara R, Barker W, Gold M, Crawford F, Mullan M. The −491A/T apolipoprotein E promoter polymorphism association with Alzheimer’s disease: independent risk and linkage disequilibrium with the known APOE polymorphism. Neurosci Lett. 1998;252:95. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viiri LE, Raitakari OT, Huhtala H, Kahonen M, Rontu R, Juonala M, Hutri-Kahonen N, Marniemi J, Viikari JS, Karhunen PJ, Lehtimaki T. Relations of APOE promoter polymorphisms to LDL cholesterol and markers of subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1298. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600033-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wahrle SE, Shah AR, Fagan AM, Smemo S, Kauwe JS, Grupe A, Hinrichs A, Mayo K, Jiang H, Thal LJ, Goate AM, Holtzman DM. Apolipoprotein E levels in cerebrospinal fluid and the effects of ABCA1 polymorphisms. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu CE, Seltman H, Peskind ER, Galloway N, Zhou PX, Rosenthal E, Wijsman EM, Tsuang DW, Devlin B, Schellenberg GD. Comprehensive analysis of APOE and selected proximate markers for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: Patterns of linkage disequilibrium and disease/marker association. Genomics. 2007;89:655. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng P, Pennacchio LA, Le Goff W, Rubin EM, Smith JD. Identification of a novel enhancer of brain expression near the apoE gene cluster by comparative genomics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1676:41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]