Abstract

Inactivation of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), a tumor suppressor gene is often associated with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). VHL inactivation leads to multitude of responses including enhanced growth factor signaling such as bFGF2, SDF-1α and HGF. Here we have identified a novel VHL inducible gene, heparan sulfatase 2 (HSulf-2) that attenuates heparan binding growth factor such as bFGF2 signaling. VHL mediated HIF-1 alpha degradation was essential to restore HSulf-2 expression. Mechanistically, HSulf-2 negatively regulated vimentin expression and knockdown of vimentin abolished cell migration. This study reveals a novel layer of regulation of heparan binding growth factor signaling via modulation of heparan sulfate by HSulf-2 in ccRCC.

Keywords: Heparan Sulfatase 2, growth factor, cell migration, VHL

1. INTRODUCTION

Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans (HSPGs) play vital role in regulating heparan sulfate binding growth factor signaling by acting as co-receptors. HSPG’s are post-translationally modified through sulfation of heparan sulfate. Heparan sulfatase 1 (HSulf-1) and Heparan sulfatase 2 (HSulf-2) are two important 6-O endosulfatases which have been identified to act on heparan 6-O sulfate moieties of HSPGs [1]. Several reports indicate that these enzymes inhibit heparan binding growth factor signaling by altering 6-O-sulfation of HSPGs [2-4]. Heparan sulfate (HS) editing at 6-O sulfate position results in decreased complex between FGFR2-bFGF resulting in decreased signaling [5]. In addition, 6-O-sulfatases have been shown to promote Wnt signaling in mouse myoblasts and pancreatic cancer cells [6,7]. Subsequently it was shown that HSulf-2 can mobilize several heparan binding growth factors [8]. HSulf-1 has been found to be downregulated in ovarian and breast cancers. At the level of gene regulation, a transcription factor, variant of HNF has also been shown as negative regulator of HSulf-1 in ovarian cancer [9]. Previous reports indicate differential role of HSulf-1 and HSulf-2 in tumorigenesis, however, both have a catalytically similar function. While HSulf-1 is considered as a tumor suppressor, HSulf-2 has been reported to be a tumor promoter [10,11] or oncogene in a cell-type dependent manner [7,12]. By modulating sulfation states of heparan sulfate, these enzymes alter the growth factor signaling at cell surface or arising through extracellular matrix [13]. Therefore, altered HS sulfation state that can be targeted by novel therapeutic agents such as sulfated oligosaccharides or heparan sulfate (HS) mimetic compounds (PG545 and PG517)[14]. HS mimetics block the interactions of growth factors to cognate receptors and co-receptors [14] much like high levels of HSulfs and can inhibit heparin binding growth factor-mediated signaling, angiogenesis and migration - thus potentially opening additional novel approaches to treating renal carcinoma.

Von Hippel Lindau is a tumor suppressor multifunctional gene and its inactivation is associated with clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma (ccRCC)[15]. VHL is part of a E3 ligase component including Elongin C, Elongin B, Cullin 2, and ring box involved in the proteolysis of Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF-1α) under oxygenated conditions. In turn, HIF-1α regulates tumor angiogenesis by regulating various target genes. While majority of the genes identified have been found to be upregulated by HIF-1α, only a handful of genes was shown to be inhibited by HIF-1α such as alpha-fetoprotein [16], carbamoyl phosphate synthetase-aspartate carbamoyltransferase-dihydroorotase (CAD) gene [17], CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-alpha [18], hepcidin [19], MutSalpha [19] and Rabaptin-5 [20]. VHL inactivation results in increased CXCR4/SDF, FGFR2/bFGF2 and c-Met/HGF signaling either due to upregulation of their respective receptors at the cell surface, or defective turnover in case of FGFR2 [21-24]. Since all these ligands are also heparan sulfate binding growth factors, we investigated the role of heparan sulfate editing enzymes in RCC because the functional role of heparan sulfate editing enzymes such as HSulf-1 and HSulf-2 in renal carcinogenesis is not known. In the present study, we found that HSulf-2 is negatively regulated by hypoxia in a HIF-1α-dependent manner. Furthermore, HSulf-2 negatively regulates cell migration by downregulating vimentin expression and bFGF2 signaling. Similarly, HS mimetics efficiently attenuated cell migration. Therefore, identification of novel components of VHL pathway will provide a better understanding of the disease and help identify new avenues of therapeutic development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell culture

Renal cancer cell lines Umrc2, Umrc3, 786-O, RCC4, 293T-HEK, A498 as well as HK-2 epithelial cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin). RCC4 (vector alone transfected) and RCC4-VHL (i.e VHL transfected) stable clones were obtained from European Collection of Animal Cell Cultures. 786-O were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (CRL-1932). 786-O cells were stably transfected with the pRC empty vector or pRC-HA-VHL expression vector to generate 786-O-vector and 786- O-VHL stable transfectants, respectively. Cells were exposed to hypoxia in a hypoxia incubator (Thermo electron Corporation). Hypoxia treatment was given to cells by incubating them at 3% oxygen for 16 hours or for indicated time intervals. PG545 and PG517 compounds were obtained from Progen Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Australia.

2.2 Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested in lysis buffer containing 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 350 mM NaCl, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mMdithiothreitol, 1 mM glycerol phosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 30% glycerol with protease inhibitors. Protein was estimated by Bradford Method and separated on SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) at room temperature for 1 h followed by incubation with the indicated antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Blot was then washed in TBST and incubation with either anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody tagged HRP and finally developed using ECL chemiluminescence. Experiments were conducted at least three times.

2.3 Determination of Glycosylation

Renal cancer cell lines protein lysates were treated with 500 and 1000U each of Endo H (Endoglycosidase, NEB) and PNGase F (Peptide:N-Glycosidase F, NEB) respectively for 1 h at 37°C according to manufacturer’s protocol (New England Biolabs). The reaction was terminated using Laemelli buffer and samples were subjected to Western immunoblot analysis using HSulf-2 and anti-clusterin antibodies. All experiments were conducted at least three times.

2.4 Lentiviral shRNA

Short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) cloned into the lentivirus vector pLKO.1-puro were chosen from the human library (MISSION TRC-Hs 1.0) and purchased as glycerol stock from Sigma. The control shRNA (non-target shRNA vector, Sigma) contains a hairpin insert that will generate siRNAs but contains five base pair mismatches to any known human gene. shRNA for HIF-1α was purchased from Open Biosystems. GFP-lentivirus vector encodes GFP when infected. Lentivirus particles were produced by transient transfection of pLKO.1-HSulf-2, pLKO.1 NTC, pLKO.1 HIF-1α, pLKO.1 HIF-2α, pZIP-vimentin along with packaging vectors (pVSV-G and pGag/pol) in 293T cells. Individual target gene sequences have been described in Table 1. The lentiviral supernatant stocks were collected 48 hours after transduction, filtered with 0.45μm filter and either used for infection or stored at −80°C. Vector titers were determined by transducing cells with serial dilutions of concentrated lentivirus, in complete growth medium containing 8μg/ml polybrene (Invitrogen). After day 4, growth medium was supplemented with puromycin (2μg/ml). The numbers of surviving colonies were counted under the microscope and titer of lentiviral stocks was calculated using the formula: Transducing units=number of colonies × lentiviral dilution. All lentiviral stocks used in the study were selected at a multiplicity of infection of 10.

Table:1.

ShRNA Target Sequences.

| shRNA target sequence for HIF-1α |

| HL718:CCTAAAGCAGTCTATTTATATT |

| shRNA target sequence for HSulf-2 |

| HW11: CAAGGGTTACAAGCAGTGTAA |

| HW13 : CCACAACACCTACACCAACAA |

| shRNA target sequence for HIF-2α |

| HB17: GCGCAAATGTACCCAATGATA |

| shRNA target sequence for Vimentin |

| V46: CGCCAGATGCGTGAAATGGAA |

| V49: CCGACACTCCTACAAGATTTA |

2.5 Real time PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared using TRIZOL reagent, reverse-transcribed with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Invitrogen) and the cDNA was amplified using SYBR-Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) using specific primers for human vimentin and ribosomal 18S subunit (Applied Biosystems) in a Light Cycler (BioRad Chromo 4). Normalization across samples was performed using the average of the constitutive gene human 18S and/or β-actin primers and calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method [25]. Binding efficiencies of primers sets for both target and reference genes were similar. All experiments were conducted at least three times.

2.6 Cell migration assays

Transwell chamber (Millipore; 8-μm pore size) assays were performed using 15,000 cells per insert seeded into the upper chamber in serum free medium. Non target clones and batch clones were trypsinized and cells were added to upper chambers. Complete growth medium was added only to lower chamber. bFGF2 was added in lower chamber in serum free medium where indicated. Cells were allowed to migrate for 16 hours followed by commassie blue staining and were counted in 8 different fields. All samples were analyzed in triplicate wells. Experiments were conducted at least three times. Results were analyzed using Student’s t test.

3. RESULTS

3.1 VHL positively regulates HSulf-2 expression in renal carcinoma cells

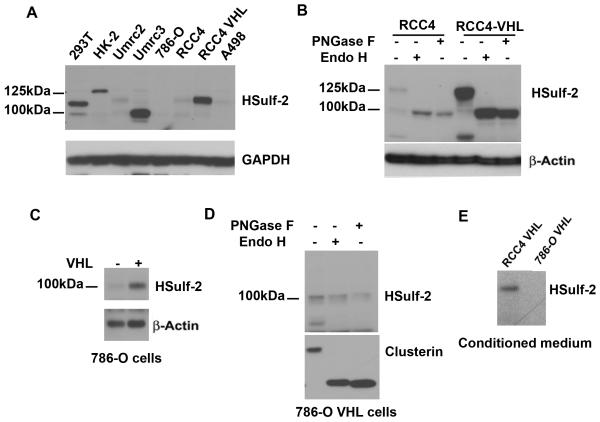

To analyze HSulf-2 expression, we utilized panel of renal cancer cell lines. Immunoblot analysis in RCC cell lines showed high levels of HSulf-2 in 293T, HK-2 cells and Umrc3 cells lines and very low levels in Umrc2, 786-O, RCC4 and A498 cells (Fig 1A). All these four cell lines and Umrc3 cells are reported to carry VHL mutation (24). Notably, cell lines expressed a 97kDa and the full length isoform at 125kDa, which could be attributed to post-translational modifications such as glycosylation.

FIGURE 1. Decreased HSulf-2 expression in VHL null or mutated renal cancer cells lines.

(A) Various renal cancer cell lines were grown and cell lysates were subjected to Western immunobloting with anti-HSulf-2 antibody. VHL defective cell lines Umrc2, 786-O, RCC4 and A498 express low levels of HSulf-2, whereas VHL supplemented RCC4 cell line express HSulf-2 protein. Equal loading was confirmed by GAPDH expression using anti-GAPDH antibody in the above samples. (B) RCC4 and RCC4-VHL were subjected to N-Glycosidases (Endo H and PNGase F) treatment as indicated in materials and methods. Samples were then subjected to Western immunoblot analysis using anti-HSulf-2 antibody. Equal loading was confirmed by anti- β actin antibody. (C) 786-O and 786-O VHL cells were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-HSulf-2 and anti-β actin antibodies. (D) 786-O VHL cells were subjected to N-Glycosidases (Endo H and PNGase F) treatment as indicated in materials and methods and subjected to Western blot analysis with indicated antibodies. (E) Secretory proteins from conditioned medium of RCC4 VHL and 786-O VHL cells were precipitated with tricholoroacetic acid treatment and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-HSulf-2 antibody. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

Since the majority of the cell lines with lower level of HSulf-2 expressions have VHL mutations, we next determined whether VHL regulates HSulf-2 expression. Western immunoblot analysis with anti-HSulf-2 antibody in VHL deficient RCC4, 786-Ocells and stably reconstituted RCC4-VHL and 786-O-VHL cells indicated low levels of HSulf-2 in RCC4 and 786-O cells whereas RCC-VHL and 786-O-VHL cells express significantly high levels of HSulf-2 (Fig 1B and 1C). Notably the RCC-VHL cells expressed the 125kDa protein, while 786-O-VHL cells expressed only the 100 kDa protein.

Since differential glycosylation could account for the differences in the molecular size, we treated RCC4 and 786-O cell lysates with N-glycosidases such as PNGase F and EndoH. Western immunoblot analysis revealed that the 125kDa HSulf-2 protein was glycosylated in RCC4-VHL cells as treatment with two different glycosidases resulted in a mobility shift to a 100kDa protein (Fig 1B). In contrast, 786-O cells did not show any change in the mobility of HSulf-2 protein upon treatment with N-glycosidases (Fig 1D). To exclude the possibility that 786-O cells are defective or deficient in N-glycosylation, we probed the same membrane with an antibody to clusterin, a well known N-glycosylated secretory protein [26]. Results shown in Figure 1D clearly shows that clusterin is glycosylated, whereas, HSulf-2 is not glycosylated. Since HSulf-2 is an extracellular sulfatase that is secreted, we next determined the extent of HSulf-2 secretion in RCC4-VHL and 786-O-VHL cells. Western blot analysis of conditioned medium from both the cell lines revealed that while, HSulf-2 was secreted in RCC4–VHL cells, HSulf-2 was not detected in the conditioned medium from 786-O VHL cells (Fig 1E).

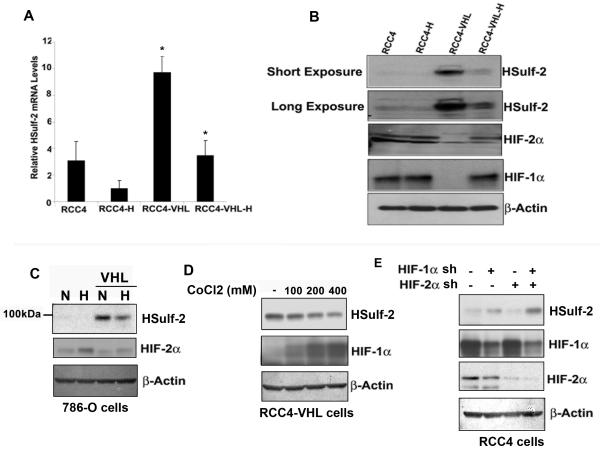

3.2 Hypoxia downregulates HSulf-2 expression in renal carcinoma cells

Since HIF proteins are targets of VHL mediated degradation and are stabilized under hypoxic conditions, we surmised that HSulf-2 expression in RCC could be regulated by hypoxia-HIF-pathway. RCC4 cells lack functional VHL and constitutively express HIF-proteins. RCC4 and RCC4-VHL cells were exposed to hypoxia (3%, 16 hours). Real time analysis was performed to evaluate HSulf-2 mRNA expression. Consistent with our Western blot analysis, RCC4 stably expressing VHL showed significantly high levels of HSulf-2 mRNA compared to RCC4 cells without VHL. Furthermore, real-time PCR analysis showed that hypoxic exposure of RCC4-VHL cells resulted in the downregulation of HSulf-2 mRNA (Fig. 2A). Data suggest that hypoxia negatively regulated HSulf-2 mRNA levels. Subsequently, Immunoblot analysis validated the HSulf-2 downregulation at the protein level (Fig. 2B). As shown in Figure 2B, while HSulf-2 expression was undetectable in RCC4 cells that constitutive express HIF-1α and HIF-2α under normoxic conditions, HSulf-2 was upregulated in RCC-VHL cells under normoxic conditions (Figs 1A, 2B, panels 3 and 4). However, hypoxia exposure of RCC4-VHL cells showed stabilization of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α and downregulation of HSulf-2 expression (Fig. 2B, lane 4). These data suggest that hypoxia could negatively regulate HSulf-2 expression at protein and RNA level. We further examined the effect of hypoxia on 786-O cells. Immunoblot analysis show that supplementation of 786-O cells with VHL upregulates HSulf-2 and exposure to 786-O VHL cells with hypoxia downregulated HSulf-2 expression (Fig 2C).

FIGURE 2. Hypoxia and hypoxia mimetic downregulate HSulf-2.

(A) RCC4 and RCC4-VHL cells were either left untreated or exposed to hypoxia (3%, 16 hours) and subjected to real time analysis with HSulf-2 and 18S primers as described in the materials and methods section *p value <0.05 and (B) Western immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-HSulf-2, HIF-1α, HIF-2α and β-actin antibodies respectively. (C) 786-O and 786-O VHL cells were either left untreated or exposed to hypoxia (3%, 16 hours) and subjected to Western immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-HSulf-2, HIF-2α and β-actin antibodies respectively. (D) RCC4-VHL cells were exposed to hypoxia mimetic agent, cobalt chloride at indicated concentrations for 24 hours. Cells were harvested and subjected to Western immunoblot analysis using anti-HSulf-2, anti-HIF-1α and anti-β-actin antibodies. (E) RCC4 cells were transduced with NTC, HIF-1α, HIF-2α and both (-1α and HIF-2α) for 48 hours followed by puromycin (2μ g/ml) treatment for 72 hours. Cells were harvested and subjected to Western immunoblot analysis using anti-HSulf-2, HIF-1α, HIF-2α and β-actin antibodies. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

Similar to hypoxia, hypoxia mimetic compounds also stabilize HIF-1α [27], therefore we next tested the effect of hypoxia mimetic compounds such as cobalt chloride (CoCl2) on HSulf-2 expression. RCC4-VHL cells were treated with various concentrations of CoCl2. Western blot analysis shows that CoCl2 can stabilize HIF-1α in a dose dependent manner resulting in the downregulation of HSulf-2 (Fig 2D). Further, to directly asses the role of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in HSulf-2 suppression, we stably knocked down HIF-1α and HIF-2α in RCC4 cells by lentiviral mediated shRNA and monitored HSulf-2 expression by western blot analysis. Our analysis shows more than 60% knockdown of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α (Fig 2E). While knockdown of HIF-1α resulted in upregulation of HSulf-2 expression in RCC4 cells, knockdown of HIF-2α alone had minimal effect. However, knockdown of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α resulted in a higher degree of HSulf-2 expression (Fig 2E, lane 4). Collectively these data suggest that HIFs negatively regulate HSulf-2 expression in ccRCC cells.

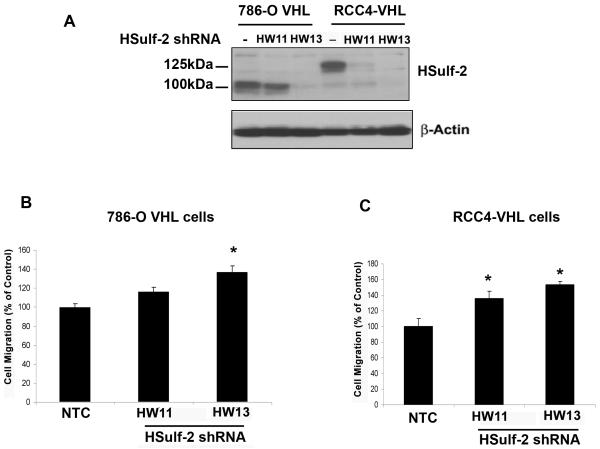

3.3 HSulf-2 knockdown in RCC-VHL cells results in increased cell migration

To determine the contribution of HSulf-2 in regulating cell migration and invasion, we generated HSulf-2 downregulated stable batch clones in RCC4-VHL cells and 786-O-VHL cells by lentiviral mediated two different shRNAs HW11 and HW13 as described in materials and methods. Western immunoblot indicated efficient downregulation of HSulf-2 by two independent shRNAs (Fig 3). Transwell migration assays showed (Figures 3B and C) that HSulf-2 depleted clones in both renal carcinoma cell lines stably expressing VHL exhibited enhanced cell migration. However, HSulf-2 knockdown did not affect cell proliferation (data not shown). These data suggest that HSulf-2 downregulation promotes cell migration.

FIGURE 3. HSulf-2 knockdown promotes cell migration.

(A) 786-O-VHL and RCC4-VHL cells were grown and transduced with non target control (NTC) and two different shRNA against HSulf-2 (HW11 and HW13). Batch clones were generated by selection under puromycin. Cells were harvested and subjected to Western immuoblot analysis using anti-HSulf-2 and β-actin antibodies. Of note, 786-O cells express 100kDa HSulf-2. (B) Batch clones of 786-O-VHL-NTC and HSulf-2 downregulated clones HW11 and HW13 were subjected to cell migration using transwell migration assay as described in materials and methods. *p value<0.05 (C) RCC4-VHL-NTC and HSulf-2 downregulated clones HW11and HW13 were subjected to cell migration using transwell migration assay as described in materials and methods. *p value =<0.05. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

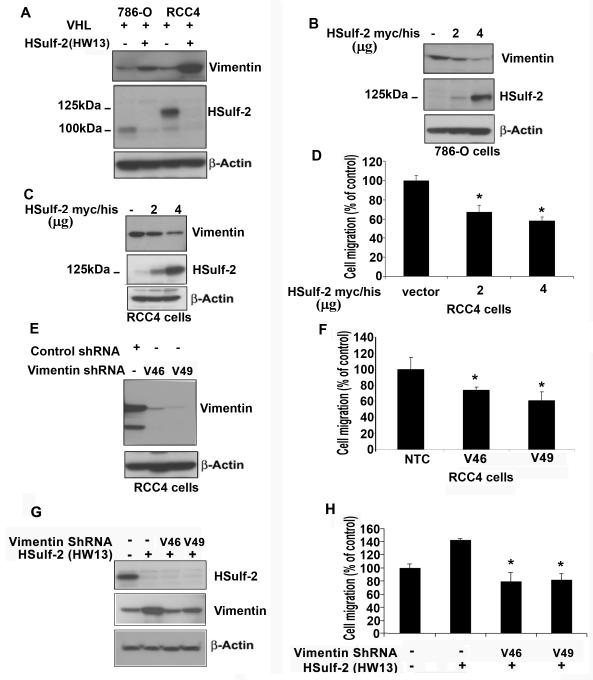

3.4 Knockdown of HSulf-2 upregulates vimentin in renal carcinoma cells

To determine the mechanism by which HSulf-2 regulates cell migration and invasion, we analyzed the effect of HSulf-2 knockdown on several proteins involved incell migration including vimentin and fibronectin. While HSulf-2 knockdown clone in 786-O-VHL and RCC4-VHL showed increase in vimentin expression (Fig 4A), whereas there was no difference in fibronectin as determined by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). We next determined the impact of HSulf-2 overexpression on vimentin expression in 786-O and RCC4 cells. 786-O and RCC4 cells which express minimal levels of HSulf-2, were transiently transfected with pcDNA 3.1 HSulf-2 myc/his plasmid and were subjected Western blot analysis. Western blot analysis revealed increased expression of HSulf-2 in both 786-O and RCC4 cells resulted in decreased vimentin expression (Fig 4B, C). Data suggest that HSulf-2 inhibited vimentin expression. Subsequently, we evaluated effect of HSulf-2 overexpression in RCC4 cells on cell migration. Transwell migration assay revealed that HSulf-2 overexpression significantly inhibited cell migration (Fig 4D). Finally, we tested the role of vimentin in cell migration in RCC4 VHL cells by downregulating vimentin using two different lentiviral shRNA against vimentin. Western blot analysis using anti-vimentin antibody shows marked knockdown of vimentin in the batch clones (Fig 4E). NTC and vimentin downregulated clones HW11 and HW13 in RCC4 cells were then subjected to cell migration as described in materials and methods. Data suggest that vimentin knockdown significantly inhibited cell migration (Fig 4F). Furthermore, vimentin downregulation in HSulf-2 depleted cells also attenuated cell migration (Fig 4G). These results show that HSulf-2 downregulates vimentin and cell migration.

FIGURE 4. HSulf-2 knockdown in 786-O-VHL and RCC4-VHL cells upregulates vimentin expression.

(A) Batch clones of 786-O-VHL and RCC4-VHL cells were transduced with NTC, HSulf-2 shRNA-HW13 were harvested and subjected to Western immubnoblot analysis using anti-vimentin, HSulf-2, and β-actin antibodies. (B) 786-O cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 HSulf-2 myc/his plasmid for 36 hours and cells were harvested and subjected with Western immunoblot analysis using anti-vimentin, HSulf-2 and anti-β-actin antibodies. (C) RCC4 cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 HSulf-2 myc/his plasmid for 36 hours and cells were harvested and subjected with Western immunoblot analysis using anti-vimentin, HSulf-2 and anti-β-actin antibodies. (D) RCC4 cells transfected with pcDNA 3.1 HSulf-2 myc/his plasmid for 36 hours and cells were harvested and subjected to transwell migration assay as described in materials and methods. *p value =<0.05. (E) RCC4 cells were transduced with NTC and two different shRNAs against vimentin (V46 and V49) and batch clones were generated. Cells were harvested and subjected with Western immunoblot analysis using anti-vimentin and anti--β-actin antibodies. (F) NTC and vimentin downregulated clones were subjected to transwell cell migration assay as described in materials and methods.(G) RCC4-VHL-HW13 cells were transduced with two different shRNAs against vimentin, V46 and V49 followed by Western blot analysis to detect HSulf-2, vimentin and β-actin levels, and (H) RCC4-VHL-HW13 and vimentin downregulated RCC4 VHL HW13 clones were subjected to transwell migration assay. *p value= =<0.05. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

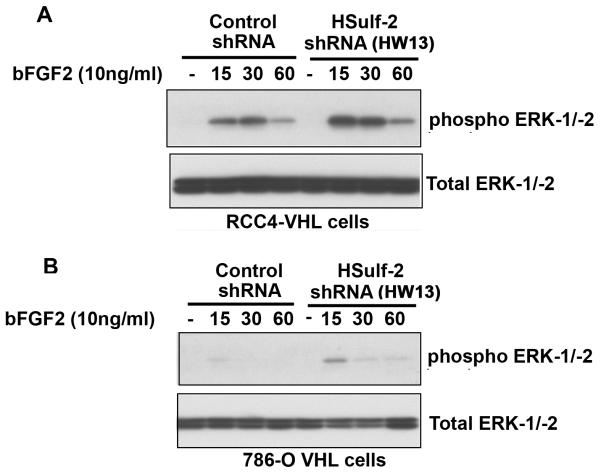

3.5 HSulf-2 knockdown enhanced bFGF2 signaling

Previous reports have indicated that HSulf-2 either negatively or positively regulate bFGF2 signaling [28,29]. Therefore, we next analyzed the effect of HSulf-2 depletion on bFGF2 signaling. Non-target control RCC4-VHL cells and HSulf-2 depleted batch clones were treated with bFGF2 (10ng/ml) for indicated intervals and downstream activation of ERK was monitored by using anti-phopshorylated ERK-1/-2 antibody by Western blot analysis. Figure 5A shows bFGF2 stimulation resulted in ERK-1/-2 activation, however in HSulf-2 depleted clones this activation was enhanced, indicating that HSulf-2 negatively regulates bFGF2 signaling. Similarly, HSulf-2 depletion in 786-O VHL cells resulted in enhanced bFGF2 signalling (Fig 5B). These data suggest that HSulf-2 knockdown promotes heparan binding growth factor signaling such as bFGF2.

FIGURE 5. HSulf-2 knockdown promotes bFGF2 signaling.

(A) RCC4-VHL-NTC and RCC4-VHL HSulf-2 shRNA HW13 , (B) 786-O-VHL NTC and 786-O-VHL HSulf-2 shRNA HW13 batch clones were serum starved for 16 hours and stimulated with bFGF2 (10ng/ml) for indicated time intervals. Cells were harvested and subjected with Western immunoblot analysis using anti-phosphoERK-1/-2 and total ERK-1-2 antibodies. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

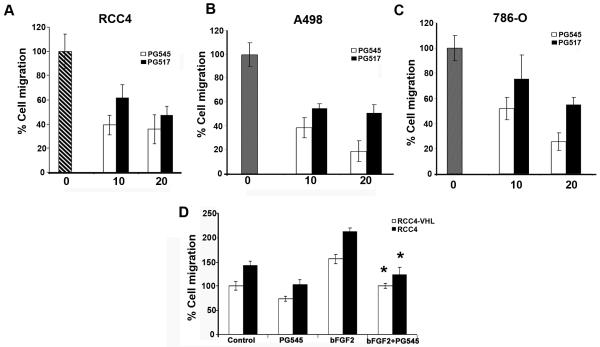

3.6 Sulfated oligosaccharides or heparan sulfate (HS) mimetic compounds (PG545 and PG517) compounds attenuate renal cancer cell migration

PG545 and PG517 sequester heparan binding growth factors and simultaneously inhibit heparanase activity with acceptable toxicological and pharmacokinetic profile in vivo [14]. We propose that, by affecting growth factor mediated signaling directly, HS mimetics may mimic Sulf activities in addition to inhibiting heparanase. Effect of PG545 and PG517 HS mimetics at (10μM and 20μM) were tested on cell migration in response to serum in RCC4, A498 and 786-O cells (Fig. 6A) by transwell migration assay as described in materials and methods. Upper chamber contained serum free medium with cells and lower chamber contained growth medium with serum. PG545 and PG517 were added in both chambers to inhibit heparanase in cells and sequester growth factors. Subsequently, we evaluated the efficacy of these compounds on cell migration of RCC4-VHL and RCC4 cells in presence or absence of bFGF2. Data indicate that bFGF2 enhanced the cell migration in RCC4 cells significantly as compared to RCC4-VHL cells. Similarly, HS mimetic compound PG545 attenuated cell migration induced by bFGF2 in both RCC4 and RCC4-VHL cells (Fig 6B). Collectively, these data shows that PG series of compounds effectively inhibited renal cancer cell migration in response to serum and bFGF2.

FIGURE 6. HS mimetic compounds (PG545 and PG517) compounds attenuate renal cancer cell migration.

Effect of HS mimetic compounds at indicated concentrations on cell migration of (A) RCC4, (B) A498 and (C) 786-O cells for 24 hours as described in materials and methods. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments. (D) RCC4 and RCC4-VHL cells were subjected to transwell cell migration assay in presence or absence of bFGF2 (10ng/ml) and PG545 (10μM) as indicated. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent mean±SD. *p value =<0.05.

4. Discussion

Very little is known about the role of heparan endosulfatases, HSulf-1 and -2 in renal cell carcinomas. While there are several reports on the altered expression of these two enzymes in various tumor types, there is scant information on the regulation of these enzymes. In the present report, we demonstrate that tumor suppressor VHL gene positively regulates heparan sulfatase 2 in renal carcinoma cell lines via degradation of HIF’s. We show that hypoxia mimetic compounds CoCl2 and low oxygen conditions downregulates HSulf-2 mRNA and protein. Conversely, HIF-1α knockdown in RCC4 cells restored HSulf-2 expression even in the absence of VHL. These data indicate that low oxygen condition, a prevalent condition in tumor microenvironment can downregulate HSulf-2 in a HIF dependent manner. Mechanistically, how HIF-α proteins regulate HSulf-2 has not been identified, however we speculate several possibilities such as by transcriptional inhibition (given the presence of hypoxia response element (HRE) such as CACGTG on HSulf-2 promoter), mRNA degradation or through regulation of other proteins which in turn regulate HSulf-2. HRE sequences has been found in many HIF-1α target genes [30]. Extracellular endosulfatases HSulf-2 in turn attenuate heparan binding growth factor such as bFGF2 signaling. Our data also articulated role of HSulf-2 in cell migration in renal cancer cell lines deficient of VHL. Overexpression of HSulf-2 significantly inhibited cell migration in renal cell carcinoma cell lines lacking HSulf-2 expression such as 786-O and RCC4. Knockdown of HSulf-2 in RCC4-VHL cells promoted bFGF2 signaling and upregulated vimentin expression leading towards increased cell migration. Upregulation of FGFR2 and vimentin expression both have been observed in clear cell renal cell carcinoma [31-34]. More specifically vimentin was identified as VHL repressible gene in RCC4 and 786-O cells [35].

Several cell lines deficient of functional VHL exhibited weak or low levels of HSulf-2 expression. Weak expression of HSulf-2 was detected in both RCC4 and 786-O cells, whereas VHL supplemented 786-O cells exhibited increased HSulf-2 expression albeit to a lesser extent as compared to VHL supplemented RCC4 cells. In contrast to RCC4 cells, we saw a non-glycosylated 100kDa form of HSulf-2 in 786-O cells. 786-O cells exclusively express HIF-2α whereas RCC4 express both HIF-1α and HIF-2α forms [36]. Whether HIF’s can regulate HSulf-2 glycosylation is an important question. However, we believe it is unlikely to be the case because we observed a 125kDa protein following overexpression of HSulf-2 construct in 786-O cells (Fig 4B) and not the endogenous 100kDa form of HSulf-2 (Fig.3A). Our data also suggests that although VHL promotes HSulf-2 expression in RCC4 cells and 786-O cells by upregulating HSulf-2 mRNA, we cannot rule out the possibility that there could be additional mechanisms(post-translational modifications) independent of VHL/HIF-1α pathway that could play a role in regulating HSulf-2 expression in 786-O and Umrc3 renal cancer cells. One such mechanism may be by post-translational regulation of HSulf-2 glycosylation. This is not surprising since glycosylation plays an important role in protein folding, stability and its secretion. Consistent with these finding HSulf-2 is not secreted in the conditioned medium of 786-O cells. In contrast, RCC4 cells secreted HSulf-2 into conditioned medium. Furthermore, non-glycosylated form of HSulf-2 in 786-O was less effective in mediating the observed effects on bFGF2 signaling and vimentin expression as compared to glycosylated HSulf-2 in RCC4 cells. Thus, limited upregulation of vimentin and bFGF2 signaling was achieved in 786-O-VHL cells compared to RCC4-VHL cells indicating decreased activity of non-glycosylated form of HSulf-2. Supporting this notion, previous report proposed that glycosylation of exogenous QSulf1 is essential for its enzymatic activity, membrane targeting and secretion [37]. Overall, we hypothesize that hypoxia via stabilizing HIF-1α acts to limit HSulf-2 expression in renal cancer cell lines. However, whether such inverse relationship is maintained in human renal cancer derived tissues remains to be determined. Therefore, further studies using mouse models and human renal cancer tissues are warranted to determine the contribution of HSulf-2 in renal cancer in vivo.

Finally, both positive and negative roles of HSulf-2 are reported in different cancer types. Tumor promoter role of HSulf-2 has been described to be dependent on its ability to activate wnt signaling whereas tumor suppressor role has been attributed to its ability to inhibit FGF2 signaling ([38,39]. More recently, HSulf-2 was found to have tumor suppressor function in breast cancer metastasis [40] and a tumor promoter activity in pancreatic, breast, and lung cancers [7,12,38]. Thus differential roles of HSulf-2 can be attributed to distinct tumor types.

Diminished HSulf’s caused increased cell migration in response to chemokines and growth factors. Novel agents such as HS mimetics can attenuate growth factor interaction with their cognate receptor, in addition to inhibiting heparanase. Our data show that these agents inhibit cell migration of renal cancer cells. Therefore, testing of HS mimetics as therapeutic compounds is of translational importance (PG545 is now entering Phase I clinical trials for advanced cancer) and on this evidence, might have utility for cancers with VHL mutation and /or loss.

Our study suggest an additional mechanism whereby enhanced heparan sulfate sulfation state as a result of HSulf-2 downregulation leads to high responsiveness towards heparan binding growth factor signaling and cell migration. In conclusion, this is the first report documenting negative regulation of heparan sulfatase 2 by HIFs in renal carcinoma cell lines. This study highlights a novel layer of regulation of heparan binding growth factor signaling by VHL/HIF-1α by potentially altering sulfation states of heparan sulfate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank members of Shridhar’s lab for insightful discussions and Dr. Dev Mukhopadhyay (Mayo Clinic) for providing us with 786-O cells with and without VHL.

This work was supported by grants from the NCI, National Institutes of Health (CA106954-04), Mayo Clinic College of Medicine (to V.S.).

The abbreviations used are

- HSulf-2

heparan sulfatase 2

- HSPG

heparan sulfate proteoglycans

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha

- VHL

von Hippel Lindau

- ERK-1/-2

Extracellular regulated kinases

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

5. REFERENCES

- 1.Morimoto-Tomita M, Uchimura K, Werb Z, Hemmerich S, Rosen SD. Cloning and characterization of two extracellular heparin-degrading endosulfatases in mice and humans. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277(51):49175–49185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205131200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai J, Chien J, Staub J, et al. Loss of HSulf-1 up-regulates heparin-binding growth factor signaling in cancer. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278(25):23107–23117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai JP, Chien J, Strome SE, et al. HSulf-1 modulates HGF-mediated tumor cell invasion and signaling in head and neck squamous carcinoma. Oncogene. 2004;23(7):1439–1447. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narita K, Chien J, Mullany SA, et al. Loss of HSulf-1 expression enhances autocrine signaling mediated by amphiregulin in breast cancer. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282(19):14413–14420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narita K, Staub J, Chien J, et al. HSulf-1 inhibits angiogenesis and tumorigenesis in vivo. Cancer research. 2006;66(12):6025–6032. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ai X, Do AT, Lozynska O, Kusche-Gullberg M, Lindahl U, Emerson CP., Jr. QSulf1 remodels the 6-O sulfation states of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans to promote Wnt signaling. The Journal of cell biology. 2003;162(2):341–351. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nawroth R, van Zante A, Cervantes S, McManus M, Hebrok M, Rosen SD. Extracellular sulfatases, elements of the Wnt signaling pathway, positively regulate growth and tumorigenicity of human pancreatic cancer cells. PloS one. 2007;2(4):e392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchimura K, Morimoto-Tomita M, Bistrup A, et al. HSulf-2, an extracellular endoglucosamine-6-sulfatase, selectively mobilizes heparin-bound growth factors and chemokines: effects on VEGF, FGF-1, and SDF-1. BMC biochemistry. 2006;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu P, Khurana A, Rattan R, et al. Regulation of HSulf-1 expression by variant hepatic nuclear factor 1 in ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 2009;69(11):4843–4850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai JP, Oseini AM, Moser CD, et al. The oncogenic effect of sulfatase 2 in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated in part by glypican 3-dependent Wnt activation. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md. doi: 10.1002/hep.23848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai Y, Yang Y, MacLeod V, et al. HSulf-1 and HSulf-2 are potent inhibitors of myeloma tumor growth in vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280(48):40066–40073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morimoto-Tomita M, Uchimura K, Bistrup A, et al. Sulf-2, a proangiogenic heparan sulfate endosulfatase, is upregulated in breast cancer. Neoplasia (New York, NY. 2005;7(11):1001–1010. doi: 10.1593/neo.05496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishop JR, Schuksz M, Esko JD. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature. 2007;446(7139):1030–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature05817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dredge K, Hammond E, Davis K, et al. The PG500 series: novel heparan sulfate mimetics as potent angiogenesis and heparanase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Investigational new drugs. 28(3):276–283. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science (New York, NY. 1993;260(5112):1317–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.8493574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazure NM, Chauvet C, Bois-Joyeux B, Bernard MA, Nacer-Cherif H, Danan JL. Repression of alpha-fetoprotein gene expression under hypoxic conditions in human hepatoma cells: characterization of a negative hypoxia response element that mediates opposite effects of hypoxia inducible factor-1 and c-Myc. Cancer research. 2002;62(4):1158–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen KF, Lai YY, Sun HS, Tsai SJ. Transcriptional repression of human cad gene by hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33(16):5190–5198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seifeddine R, Dreiem A, Blanc E, et al. Hypoxia down-regulates CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-alpha expression in breast cancer cells. Cancer research. 2008;68(7):2158–2165. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peyssonnaux C, Zinkernagel AS, Schuepbach RA, et al. Regulation of iron homeostasis by the hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs) The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117(7):1926–1932. doi: 10.1172/JCI31370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Roche O, Yan MS, et al. Regulation of endocytosis via the oxygen-sensing pathway. Nature medicine. 2009;15(3):319–324. doi: 10.1038/nm.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staller P, Sulitkova J, Lisztwan J, Moch H, Oakeley EJ, Krek W. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 downregulated by von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor pVHL. Nature. 2003;425(6955):307–311. doi: 10.1038/nature01874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakaigawa N, Yao M, Baba M, et al. Inactivation of von Hippel-Lindau gene induces constitutive phosphorylation of MET protein in clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer research. 2006;66(7):3699–3705. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koochekpour S, Jeffers M, Wang PH, et al. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene inhibits hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-induced invasion and branching morphogenesis in renal carcinoma cells. Molecular and cellular biology. 1999;19(9):5902–5912. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu T, Adereth Y, Kose N, Dammai V. Endocytic function of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein regulates surface localization of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and cell motility. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281(17):12069–12080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511621200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhasarathy A, Kajita M, Wade PA. The transcription factor snail mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transitions by repression of estrogen receptor-alpha. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md. 2007;21(12):2907–2918. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart EM, Aquilina JA, Easterbrook-Smith SB, et al. Effects of glycosylation on the structure and function of the extracellular chaperone clusterin. Biochemistry. 2007;46(5):1412–1422. doi: 10.1021/bi062082v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Triantafyllou A, Liakos P, Tsakalof A, Georgatsou E, Simos G, Bonanou S. Cobalt induces hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) in HeLa cells by an iron-independent, but ROS-, PI-3K- and MAPK-dependent mechanism. Free radical research. 2006;40(8):847–856. doi: 10.1080/10715760600730810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holst CR, Bou-Reslan H, Gore BB, et al. Secreted sulfatases Sulf1 and Sulf2 have overlapping yet essential roles in mouse neonatal survival. PloS one. 2007;2(6):e575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai JP, Sandhu DS, Yu C, et al. Sulfatase 2 up-regulates glypican 3, promotes fibroblast growth factor signaling, and decreases survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md. 2008;47(4):1211–1222. doi: 10.1002/hep.22202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wenger RH, Stiehl DP, Camenisch G. Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Sci STKE. 2005;2005(306):re12. doi: 10.1126/stke.3062005re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Champion KJ, Guinea M, Dammai V, Hsu T. Endothelial function of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene: control of fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling. Cancer research. 2008;68(12):4649–4657. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L, Qian J, Singh H, Meiers I, Zhou X, Bostwick DG. Immunohistochemical analysis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, renal oncocytoma, and clear cell carcinoma: an optimal and practical panel for differential diagnosis. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2007;131(8):1290–1297. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-1290-IAOCRC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams AA, Higgins JP, Zhao H, Ljunberg B, Brooks JD. CD 9 and vimentin distinguish clear cell from chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. BMC clinical pathology. 2009;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6890-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tun HW, Marlow LA, von Roemeling CA, et al. Pathway signature and cellular differentiation in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PloS one. 5(5):e10696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maxwell PH, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ. Identification of novel hypoxia dependent and independent target genes of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumour suppressor by mRNA differential expression profiling. Oncogene. 2000;19(54):6297–6305. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, et al. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399(6733):271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ambasta RK, Ai X, Emerson CP., Jr. Quail Sulf1 function requires asparagine-linked glycosylation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282(47):34492–34499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706744200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lemjabbar-Alaoui H, van Zante A, Singer MS, et al. Sulf-2, a heparan sulfate endosulfatase, promotes human lung carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 29(5):635–646. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamanna WC, Frese MA, Balleininger M, Dierks T. Sulf loss influences N-, 2-O-, and 6-O-sulfation of multiple heparan sulfate proteoglycans and modulates fibroblast growth factor signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283(41):27724–27735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peterson SM, Iskenderian A, Cook L, et al. Human Sulfatase 2 inhibits in vivo tumor growth of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer xenografts. BMC cancer. 10:427. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]