Abstract

Distinguishing drug-induced liver injury (DILI) from idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) can be challenging. We performed a standardized histologic evaluation to explore potential hallmarks to differentiate AIH vs. DILI. Biopsies from patients with clinically well-characterized DILI (n=35, including 19 hepatocellular injury [HC] and 16 cholestatic/mixed injury [CS]) and AIH (n=28) were evaluated for Ishak scores, prominent inflammatory cell types in portal and intra-acinar areas, presence or absence of emperipolesis, rosette formation and cholestasis in a blinded fashion by 4 experienced hepatopathologists. Histologic diagnosis was concordant with clinical diagnosis in 65% of cases; but full agreement on final diagnosis among the 4 pathologists was complete in only 46% of cases. Interface hepatitis, focal necrosis and portal inflammation were present in all the evaluated cases but were more severe in AIH (p<0.05) than DILI (HC). Portal and intra-acinar plasma cells, rosette formation, and emperiopolesis were features that favored AIH (p<0.02). A model combining portal inflammation, portal plasma cells, intra-acinar lymphocytes and eosinophils, rosette formation, and canalicular cholestasis yielded an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.90 in predicting DILI (HC) vs. AIH. All Ishak inflammation scores were more severe in AIH than DILI (CS) (p≤0.05). The 4 AIH-favoring features listed above were consistently more prevalent in AIH while portal neutrophils and intracellular (hepatocellular) cholestasis were more prevalent in DILI (CS) (p<0.02). The combination of portal inflammation, fibrosis, portal neutrophils and plasma cells, and intracellular (hepatocellular) cholestasis yielded an AUC of 0.91 in predicting DILI (CS) vs. AIH.

Conclusion

While overlap of histologic findings exists for AIH and DILI, sufficient differences exist so that pathologists can use the pattern of injury to suggest the correct diagnosis.

Keywords: drug-induced liver injury, hepatocellular damage, cholestatic damage, autoimmune hepatitis, drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis, histology, Ishak scores, rosette formation, portal inflammation

BACKGROUND

Clinical diagnoses of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and drug-induced liver injury (DILI) are challenging since both conditions have heterogeneous disease manifestations clinically as well as histopathologically. These conditions are mediated by immunological reactions and thus show considerable resemblance in clinical and histopathologic features (e.g., autoantibodies, plasma cells and eosinophils). Manifestations of DILI can significantly vary even among cases caused by a single agent. For instance, some drugs (e.g., statins, minocycline, nitrofurantoin, infliximab) can cause idiosyncratic hepatocellular or cholestatic liver injury in some patients and autoimmune hepatitis - accompanied by evident autoimmunity and/or HLA haplotypes – in others.1–3 Further, it is often difficult to differentiate idiopathic AIH from AIH triggered by drugs in a clinical setting. Since it is practically impossible to exclude potential drug involvement in some cases, the differential diagnosis of idiopathic AIH vs. DI-AIH can be extremely difficult. On the other hand, timely diagnosis and proper management are critical in both conditions.4–7 Early immunosuppressive therapy typically contains disease activity in patients with idiopathic AIH and can lead to disease remission.6, 7 Similarly, prompt identification and discontinuation of offending drugs halts ongoing liver injury in cases with DILI.4 Failure to properly treat AIH and DILI could result in clinically devastating acute or chronic outcomes.4, 5

While AIH has some typical histologic patterns of injury, DILI may mimic any non-DILI pattern of injury. Currently, the role of liver biopsy evaluation in differentiating AIH from DILI remains uncertain. The histologic classification of DILI has been reported recently along with detailed descriptions of histologic features and corresponding differential diagnosis for each injury pattern.8 Characteristic histologic features of AIH have been also well documented in the literature.9, 10 Interface hepatitis, lymphocytic/lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates in portal tracts extending into the lobule, emperipolesis (presence of an intact lymphocyte within cytoplasm of a hepatocyte), and hepatocyte rosette formation are considered as common findings of AIH and are used in the recently published simplified criteria for the diagnosis of AIH.11 However, there is no individual histologic feature that is absolutely indicative of either DILI or AIH; thus, the evaluation of liver biopsy in determining AIH vs. DILI may be a significant challenge. Previous histologic evaluations have been independently done on either DILI or AIH, but the relative frequency and/or degree of each histologic feature between the two entities remain unexplored. A better understanding of the spectrum of histologic features and/or the severity of the features might be helpful in distinguishing AIH from DILI.

In this study, we performed a detailed, blinded histologic evaluation on liver biopsies from clinically well characterized cases of AIH and DILI in a standardized manner. Our specific aims were 1) to characterize the histologic features in comparison of AIH vs. DILI, 2) to explore potential histologic hallmarks (or combination of histologic features) to differentiate AIH vs. DILI, and 3) to evaluate a diagnostic value of liver biopsy in this differential diagnosis. We also performed a subgroup analysis to compare the histologic features of DI-AIH vs. AIH to explore potential histologic hallmarks for DI-AIH vs. AIH.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study materials

We evaluated 63 liver biopsies of clinically well-characterized cases of AIH and DILI. Cases of AIH (N=28) were obtained from the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA. The diagnosis of AIH was made by experienced hepatologists based on the presence of autoantibodies and/or gamma globulins with compatible histology and exclusion of competing etiologies. The clinical information and histologic data were collected at the time of their first AIH diagnosis via medical chart review. Cases of DILI (N=35) were obtained from the Spanish DILI registry (Málaga, Spain), Hospital Clinic (Barcelona, Spain), and Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA). The diagnosis of DILI was made at each site using a standardized causality assessment, Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) and/or based on clinical judgment by experienced hepatologists. When the RUCAM was used, only cases assessed as highly probable or probable were included for this study. DILI cases were then sub-classified into two categories using the criteria of the International Consensus Meeting for Liver Injury applied to the laboratory data at their first visit with liver injury events12: ‘hepatocellular injury (HC)’ (n=19) and ‘cholestatic injury (CS)’ (n=16). Cases with mixed injury were included in the category of ‘cholestatic injury (CS)’. The 35 DILI cases included 7 cases (6 HC cases and 1 CS case) of DI-AIH. The diagnosis of DI-AIH was made based on the international criteria and/or the recent simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis (probable or definite).11, 13 Relevant clinical information at the time of diagnosis was collected from each site. The study was approved by the Mayo institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients for participation in medical research.

Histologic evaluation

The 63 biopsy slides were evaluated concomitantly by 4 experienced hepatopathologists (EMB, DEK, RM, TCS) blinded to the clinical information using a standardized histologic scoring sheet. Scoring was done by consensus, but the final diagnostic categorization (DILI, AIH or indeterminate) was recorded individually. The features listed in Table 1 were scored and recorded in the standardized scoring sheets. The presence or absence of chronic hepatitic patterns and acute hepatitic patterns was recorded to characterize the cases based on their necroinflammatory patterns.8 The degree of inflammation and fibrosis was graded according to the Ishak scoring system.14 The AIH typical histological findings (rosettes, emperipolesis) were also recorded.11 To assess the character of the inflammatory cell types (i.e., neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells), prominent infiltrates were those that were readily noted on low power examination. On higher power evaluation, the type and extent of each inflammatory cell type was confirmed and the more prominent cell types were recorded separately for portal tracts and parenchyma.

Table 1.

Histologic features evaluated in this study

| Histologic features | |

|---|---|

| Chronic hepatitis pattern | Yes or no |

| Acute hepatitis pattern | Yes or no |

| Ishak scores | |

| Interface hepatitis | 0 to 4 |

| Confluent necrosis | 0 to 6 |

| Focal necrosis | 0 to 4 |

| Portal inflammation | 0 to 4 |

| Fibrosis | 0 to 6 |

| Prominent inflammatory cell types in portal area* | |

| Neutrophils | Yes or no |

| Eosinophils | Yes or no |

| Lymphocytes | Yes or no |

| Plasma cells | Yes or no |

| Other cells | Yes or no |

| Prominent inflammatory cell types in intra-acinar areas* | |

| Neutrophils | Yes or no |

| Eosinophils | Yes or no |

| Lymphocytes | Yes or no |

| Plasma cells | Yes or no |

| Other cells | Yes or no |

| Emperipolesis | Yes or no |

| Rosette formation | Yes or no |

| Cholestasis | Yes or no |

| Intracellular (hepatocellular) | Yes or no |

| Canalicular | Yes or no |

| Cholangiolar | Yes or no |

| Bile duct injury | Yes or no |

| Endophlebitis | Yes or no |

| Epithelioid granulomas | Yes or no |

| Steatohepatitis | Yes or no |

Prominent infiltrates were defined as those that were readily noted on low power examination.

Following the histologic evaluation, agreement/disagreement among the 4 pathologists was recorded for histologic diagnosis (DILI, AIH, or indeterminate) and the rate of concordance was calculated as number of pathologists in agreement divided by 4. The final histopathologic diagnosis was determined based on the diagnosis agreed on with the highest number of pathologists.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SD for continuous variables or proportion of patients with a condition. We described the concordance rate between clinicopathologic diagnosis and histologic diagnosis and rate of agreement on histologic diagnosis among the 4 pathologists in three groups, AIH, DILI (HC), and DILI (CS), and one sub-group (DI-AIH). Ishak scores and other histologic features were compared between 1) AIH vs. DILI-HC, 2) AIH vs. DILI-CS, and 3) AIH vs. DI- AIH, using Wilcoxon-rank sum test, Chi-square tests, or Fisher’s exact tests.

Multiple logistic regression models to predict 1) DILI (HC) cases vs. AIH and 2) DILI (CS) cases vs. AIH were developed. Variables associated with p<0.2 in the univariate analyses were considered in the models. When significant co-linearity (r>0.5) existed between variables, one of the variables was included in the model at a time. The final models were determined by backward elimination. Performance of the prediction models was assessed by an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC)

For analyses, we used JMP statistical software version 7.0 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC) and considered differences statistically significant when the p-values were less than 0.05. All P values presented are two-sided and have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Clinical characteristics of patients with AIH and DILI are summarized in Table 2a and 2b. Mean age and female gender of the AIH vs. DILI population were 49±18 years vs. 52±18 years (p=0.516) and 71% female vs. 49% female (p=0.07). Incriminated drugs in the 35 DILI cases are also listed in Table 2b. Median duration of exposure to the incriminated drugs was 29 days, ranging from less than 24 hours to 4 years. Among the 28 AIH cases, 15 (53.6%) had serum bilirubin levels greater than 3.0 mg/dl at baseline.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of a) AIH cases and b) DILI cases

| (a) AIH cases | Summary statistics (n=28) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 49 ± 18 |

| Female, % | 71% (20) |

| Histology, compatible/typical % | 96% (27)/ 4% (1) |

| Baseline ALT, IU/L | 1061 (708,1597)# |

| Baseline AST, IU/L | 1021 (536,1629)# |

| Baseline ALP, IU/L | 286 (182,512)# |

| Baseline total Bilirubin, mg/dl | 3.6 (1.1,15.0)# |

| (b) DILI cases | Summary statistics (n=35) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 52 ± 18 |

| Female, % | 49% (17) |

| Hepatocellular injury (HC) | 54% (19) |

| Cholestatic/mixed (CS) | 46% (16) |

| DI- AIH* | 20% (7) |

| Median duration of treatments, days | 29 (6,141)# |

| Incriminated drugs HC cases |

Amoxicillin (1), Bentazepam (1), Ebrotidine(3), Ecstasy (1), Fluvastatin(2), Ibuprofen (1), Infliximab (1), isonia- zid (1), Irbesartan (1), Levofloxacin (1), meloxicam (1), Metformin (1), Niacin(1), Nitrofurantoin (1), Omepra- zole (1), Aesculus Hippocastanum (Varicid®)(1) |

| CS cases | Amoxicillin (4), Atrovastatin (1), Cassia angustifolia (1), Efalizumab (1), Fenofibrate (1), Flunarizina (1), Fluvas-tatin(1), Indomethacin (1), Levetiracetam (1), Niacin(1), Salazopirina (1), telmisartan (1), Valaciclovir (1) |

| DI-AIH cases | Efalizumab (1), Fluvastatin(2), Infliximab (1), Irbesartan (1), meloxicam (1), Nitrofurantoin (1), |

Reference ranges of serum ALT, AST, and total bilirubin were: 7–55 U/L (males) and 7–45 U/L(females) for ALT, 8–48 U/L(males) and 8–43 U/L(females) for AST, and 0.1–1.0 mg/dL for total bilirubin. ALP reference range is age- and gender- dependent, and not provided.

Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: 6 cases were HC, while one case was CS.

Median (25th, 75 th)

Concordance rate of clinicopathologic vs. histologic diagnosis

The data are summarized in Table 3. Overall 65% of the cases (41) were concordantly diagnosed: 71.4% (20) of AIH cases and 60.0% (21) of DILI cases. There was no significant difference in the concordance rate for AIH cases vs. that for DILI cases (Chi-square test, p=0.45). In contrast, 22 cases (35%) were diagnosed as indeterminate or were suspected of being something other than AIH or DILI. Three (15.8%) DILI (HC) cases and 2 (12.5%) DILI (CS) were diagnosed as AIH. No AIH cases were diagnosed as DILI.

Table 3.

Agreement between clinical and histological diagnosis for AIH, DILI (HC), and DILI (CS)

| Clinicopathologic diagnosis | N | Histological diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIH | DILI | Indeterminate | ||

| AIH | 28 | 71.4% (20) | 0% (0) | 28.6% (8) |

| DILI (HC) | 19 | 15.8% (3) | 57.9% (11) | 26.3% (5) |

| DILI (CS) | 16 | 12.5% (2) | 62.5% (10) | 25.0% (4) |

| DI-AIH* | 7 | 57.1%(4) | 28.6%(2) | 14.3%(1) |

7 cases, 6 DILI (HC) and 1 DILI (CS), were separately analyzed as a subgroup.

In the subgroup of DI-AIH cases (N=7), 4 (57.1%) were histologically diagnosed as AIH, while 2 (28.6%) and 1(14.3%) were diagnosed as DILI and indeterminate respectively.

Agreement among the pathologists on histologic diagnosis

Overall complete agreement on histologic diagnosis among the 4 pathologists was found in 46% (29 of the 63 cases). Individually, complete agreement in AIH cases, DILI (HC) cases, and DILI (CS) cases were 46.4%, 42.1% and 50.0%, respectively, and no significant difference was noted among the three groups (Chi-square test, p=0.89).

In the sub-group of DI-AIH, there was complete agreement on the histologic diagnosis in 2 of 7 cases. The rate of complete agreement in DI-AIH cases was lower than that in non-autoimmune DILI (n=28) cases although it did not reach statistical significance (28.6% vs. 50.0%, Fisher’s exact test, p=0.42).

Comparison of Histologic Features between AIH and DILI cases

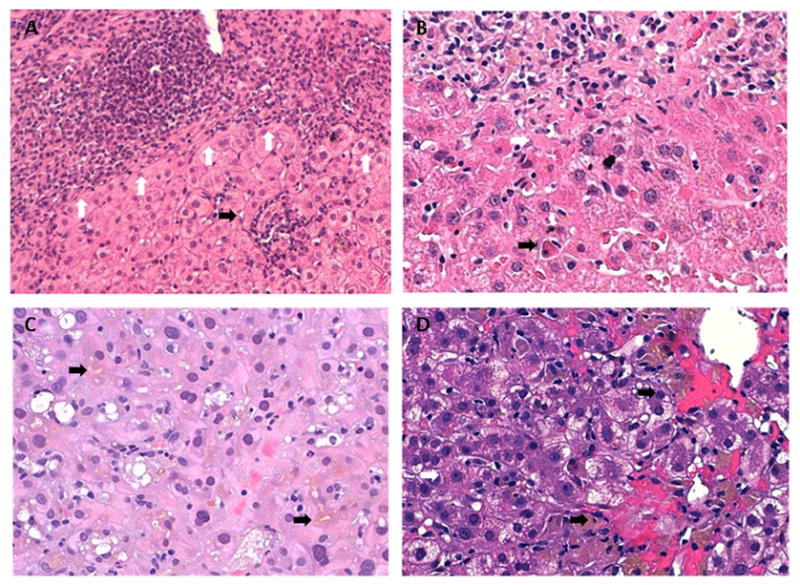

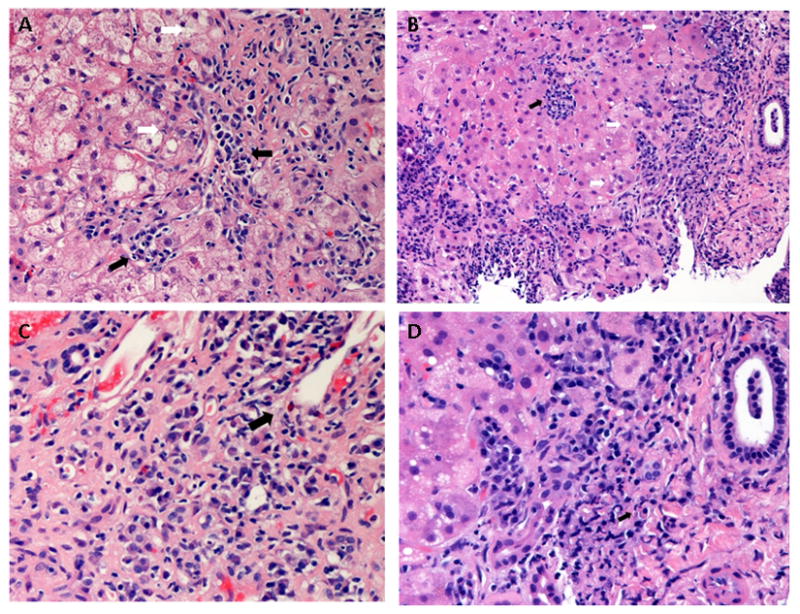

The data of the comparison between AIH vs. DILI (HC) and DILI (CS) are summarized in Table 4. Histologic pictures of representative cases are shown in Figure 1 and 2. Significant overlap of histologic findings was observed for AIH and DILI (HC). Interface hepatitis, focal necrosis and portal inflammation were present in all cases of AIH and DILI (HC), but were more severe in AIH (p<0.05). Portal and intra-acinar plasma cells, rosette formation, and emperiopolesis were features that favored AIH (p<0.05) (Table 4). Prominent intra-acinar eosinophils tended to be more frequent in AIH (p=0.086).

Table 4.

Comparison of Histologic features/scores between AIH vs. DILI (HC)

| AIH | DILI (HC) | DILI (CS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histological findings | (N=28) | (N=19) | P-value vs. AIH | (N=16) | P-value vs. AIH |

| Chronic hepatitic pattern | 80.8% | 79.0% | 1.000* | 92.9% | 0.307 |

| Acute hepatitic pattern | 59.3% | 52.6% | 0.655 | 18.8% | 0.010 |

| Ishak scores | |||||

| Interface hepatitis | 3.6±0.7 | 2.8±1.3 | 0.030 | 1.9±1.6 | 0.0002 |

| Confluent necrosis | 2.8±2.8 | 2.1±2.6 | 0.383 | 0.6±1.5 | 0.006 |

| Focal necrosis | 3.6±0.7 | 3.1±1.0 | 0.049 | 2.4±1.4 | 0.002 |

| Portal inflammation | 2.1±0.8 | 1.6±0.5 | 0.030 | 1.4±0.6 | 0.007 |

| Fibrosis | 1.9±1.4 | 1.6±1.3 | 0.378 | 1.1±1.3 | 0.052 |

| AIH typical findings | |||||

| Interface hepatitis | 100% | 100% | - | 75% | 0.014* |

| Emperipolesis | 75.0% | 36.8% | 0.009 | 31.3% | 0.005 |

| Rosette formation | 75.0% | 41.1% | 0.023 | 37.5% | 0.014 |

| AIH compatible features | 100% | 94.4% | 0.409* | 57.1% | 0.0008* |

| Prominent cell type | |||||

| -Portal | |||||

| Neutrophils | 3.6% | 15.8% | 0.289* | 31.3% | 0.019* |

| Lymphocytes | 53.6% | 73.7% | 0.164 | 68.8% | 0.325 |

| Plasma cells | 85.7% | 31.6% | 0.0002 | 25.0% | 0.0001 |

| Eosinophils | 60.7% | 41.2% | 0.210 | 37.5% | 0.138 |

| -Intra-acinar | |||||

| Neutrophils | 3.6% | 5.3% | 1.000* | 12.5% | 0.543* |

| Lymphocytes | 60.7% | 79.0% | 0.188 | 75.0% | 0.336 |

| Plasma cells | 67.9% | 21.1% | 0.002 | 18.8% | 0.002 |

| Eosinophils | 32.1% | 10.5% | 0.086 | 18.8% | 0.487* |

| Cholestasis | 10.7% | 31.6% | 0.129* | 37.5% | 0.054* |

| Intracellular | 7.1% | 15.8% | 0.381* | 37.5% | 0.019* |

| Canalicular | 10.7% | 31.6% | 0.129* | 31.3% | 0.118* |

| Cholangiolar | 3.6% | 5.3% | 1.000* | 0.0% | 1.000* |

| Others | |||||

| Bile duct injury | 57.1% | 52.9% | 0.761 | 56.3% | 0.954 |

| Endophlebitis | 25.0% | 10.5% | 0.278* | 12.5% | 0.451 |

| Epithelioid granulomas | 3.6% | 5.9% | 1.000* | 0.0% | 1.000* |

| Steatohepatitis | 3.6% | 0.0% | 1.000* | 0.0% | 1.000* |

P-values are from Chi-square tests (or Fisher’s exact tests*) or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

Figure 1.

Drug Induced Liver Injury. (A) A markedly expanded portal tract (upper) with marked, plasma cell rich inflammation and interface activity (white arrows). There are scattered foci of inflammation in the lobules (black arrow), but hepatocyte rosettes are not seen. (B) The portal tract (upper) has mixed chronic inflammation predominated by plasma cells. There is interface activity and foci of spotty necrosis (white arrow) within the lobules adjacent to the portal tract. A single acidophil body (apoptotic body) is also seen near the center lower portion of the field (black arrow). (C) In this field, the hepatocytes are swollen and have densely eosinophilic cytoplasm and marked anisonucleosis. There is lobular disarray and canalicular cholestasis (black arrows). A mild inflammatory infiltrate is seen; it is predominantly characterized by polymorphonuclear leukocytes in small aggregates. Scattered macrovesicular steatosis is noted. (D) The perivenular hepatocytes are swollen and some have reticulated cytoplasm. Some of the hepatocytes are forming rosettes (white arrow). There is hemorrhage around the terminal hepatic venule (black arrows). Numerous pigmented Kupffer cells are noted in the sinusoids, either in groups or as single cells. In addition, inflammatory cells appear to be within the sinusoids, including plasma cells.

Figure 2. Autoimmune hepatitis.

(A) Marked interface activity with disruption of the limiting plate (middle, white arrows). Adjacent hepatocytes are swollen, suggesting hepatocyte injury. The interface activity is dominated by plasma cells (black arrows). (B) An expanded portal tract (right) with marked interface activity (white arrows). There is spotty lobular inflammation composed mainly of lymphocytes (black arrow). Prominent plasma cell infiltration is present. (C) Massive portal expansion and severe interface activity with prominent plasma cell infiltration. Scattered eosinophils are also noted (black arrow). (D) Higher magnification shows the involvement of plasma cells in the interface activity. Russell bodies are seen in some plasma cells (black arrow).

Significant overlap of histologic findings was also noted in the comparison of AIH vs. DILI (CS) (Table 4). However, AIH was more frequently had an ‘acute hepatitic pattern’ of injury and was associated with higher scores of interface hepatitis, confluent necrosis, focal necrosis, and portal inflammation (all p≤0.05). Interface hepatitis (p=0.014), rosette formation (p=0.005), emperiopolesis (p=0.014), portal plasma cells (p=0.0001), and intra-acinar plasma cells (p=0.002) were more prevalent in AIH. Portal neutrophils (p=0.019) and hepatocellular cholestasis (p=0.019) were more prevalent in DILI (CS).

Combinations of the histologic features in predicting DILI vs. AIH

Prediction models using combinations of the histologic features were developed as described before and are shown in Table 5. A model combining portal inflammation, portal plasma cells, intra-acinar lymphocytes and eosinophils, rosette formation, and canalicular cholestasis yielded an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.90 in predicting DILI (HC) vs. AIH. The presence of prominent intra-acinar lymphocytes and canalicular cholestasis favored the diagnosis of DILI, while more severe portal inflammation, portal plasma cells, intra-acinar eosinophils, and rosette formation favored the diagnosis of AIH. On the other hand, a model combining portal inflammation, focal necrosis, fibrosis, portal neutrophils, and intracellular (hepatocellular) cholestasis yielded an AUC of 0.90 in predicting DILI (CS) vs. AIH, while a model replacing focal necrosis with the presence of prominent portal plasma cells yielded an AUC of 0.91. In these models, portal neutrophils and intracellular (hepatocellular) cholestasis favored the diagnosis of DILI (CS) while all other features favored the diagnosis of AIH.

Table 5.

Models to predict a) DILI (HC) vs. AIH and b) DILI (CS) vs. AIH

| Model for DILI (HC) vs. AIH | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AUROC = 0.90 | |||

| Estimates | SE | p-value | |

| Intercept | 1.304 | 1.510 | 0.388 |

| Portal inflammation* | −0.939 | 1.080 | 0.384 |

| Prominent intra-acinar lymphocytes | 1.832 | 1.116 | 0.101 |

| Prominent intra-acinar eosinophils | −1.871 | 1.358 | 0.168 |

| Cholestasis-canalicular | 1.700 | 1.051 | 0.106 |

| Prominent portal-plasma cells | −2.177 | 0.891 | 0.015 |

| Rosette formation | −1.659 | 0.895 | 0.064 |

| Models for DILI (CS) vs. AIH | |||

| Model 1 | AUROC = 0.90 | ||

| Estimates | SE | p-value | |

| Intercept | 2.193 | 1.510 | 0.147 |

| Portal inflammation* | −1.773 | 1.112 | 0.111 |

| Fibrosis** | −1.951 | 1.270 | 0.124 |

| Prominent portal-neutrophils | 2.291 | 1.388 | 0.099 |

| CS-intracellular | 2.709 | 1.490 | 0.069 |

| Focal necrosis*** | −1.738 | 1.233 | 0.159 |

| Model 2 | AUROC = 0.91 | ||

| Estimates | SE | p-value | |

| Intercept | 3.844 | 2.189 | 0.079 |

| Portal inflammation* | −2.402 | 1.413 | 0.089 |

| Fibrosis** | −2.376 | 1.518 | 0.118 |

| Prominent portal-neutrophils | 2.500 | 1.389 | 0.072 |

| CS-intracellular | 3.474 | 1.853 | 0.061 |

| Prominent portal-plasma cells | −3.220 | 1.309 | 0.014 |

Ishak scores of portal inflammation were dichotomized in the models (>=2, yes or no).

Ishak scores of fibrosis were dichotomized in the model (>=1, yes or no).

Ishak scores of focal necrosis were dichotomized in the model (>=4, yes or no).

Subgroup analysis of autoimmune hepatitis vs. drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis

We analyzed the 7 cases of DI-AIH vs. AIH to characterize potential discriminating histologic features (Supplemental Table). This small sub-group analysis showed that severity of inflammation and fibrosis (Ishak scores) and frequency of AIH-specific findings were comparable between AIH and DI-AIH. However, marked bridging fibrosis (Ishak score ≥ 4) was only observed in AIH cases (14.8%). Prominent intra-acinar lymphocyte infiltration tended to be more frequently observed in DI-AIH (17/28 vs. 7/7, Fisher’s Exact test, p=0.07). Canalicular/intracellular (hepatocellular) cholestasis was observed in some of the AIH cases (3/28 and 2/28, respectively).

DISCUSSION

We performed a standardized, detailed histologic evaluation of well-characterized idiopathic AIH and DILI cases in a blinded manner to delineate discriminating histologic features and determine the role of histologic evaluation in this differential diagnosis. While there is overlap of histologic findings for AIH and DILI, we show that pathologists can utilize combinations of features to suggest the correct diagnosis even in the absence of clinical information. Further, the results of our preliminary modeling effort suggested that, once independently validated in a larger study, models using the combined information may assist histologic differential diagnosis and provide a simple and standardized way to calculate an evidence-based probability for each disease.

We documented the daunting histologic overlap between AIH and DILI. Not surprisingly, a chronic hepatitic pattern, as opposed to an acute hepatitis pattern, was commonly seen in AIH. But, as previously suggested,8 a chronic hepatitic pattern was also more frequent than an acute pattern in both types of DILI (HC and CS). Similarly, histologic findings often cited as “typical” of AIH were also observed in a significant proportion of DILI cases, including interface hepatitis (89%), emperipolesis (34%), and rosette formation (40%). Thus, while some findings are typical of AIH,11 they are clearly not pathognomonic.

In the comparison of AIH vs. DILI (HC), the main findings of chronic hepatitic pattern, interface hepatitis and portal inflammation were present in all cases with AIH and DILI (HC) but generally more severe in AIH. Prominent eosinophil infiltration, which has been regarded as one of the histologic findings suggesting DILI,8 is not useful in the differential diagnosis with AIH. Our standardized comparative histologic evaluation demonstrated that prevalence of prominent eosinophil infiltrates in portal and intra-acinar areas was, in fact, higher among AIH cases vs. DILI cases (both in HC and CS). Although the difference was not statistically significant in univariate analyses, a prominent intra-acinar eosinophil infiltrate was one of the predictors in our multivariable analysis that favored AIH over DILI (HC). Intra-acinar lymphocytes and canalicular cholestasis favored DILI (HC) in the same model, while rosette formation, portal plasma cells, and relatively severe portal inflammation favored AIH. This suggests that the combined observation of cholestasis, inflammation (types of infiltrates and area), and degree of inflammation (Ishak scores) can help discriminate AIH vs. DILI (HC). Based on the models, having 1) prominent intra-acinar lymphocyte infiltrate or canalicular cholestasis without the 4 AIH-favorable features (portal inflammation score of >=2, rosette formation, prominent portal plasma infiltrates and prominent intra-acinar eosinophils) or 2) the combination of prominent intra-acinar lymphocyte infiltrate, canalicular cholestasis, and less than 2 of the 4 AIH-favorable features is more likely to be DILI (HC) than AIH.

In comparing AIH to DILI (CS), a chronic hepatitic pattern was frequently seen in both conditions. The acute hepatitic pattern of injury was less common in DILI-CS, and AIH cases typically had higher scores for confluent necrosis, focal necrosis, and fibrosis. Models including fibrosis, portal inflammation, intracellular (hepatocellular) cholestasis, prominent portal neutrophil infiltrates, and focal necrosis (or portal plasma cell infiltrates) discriminated our cases of DILI (CS) from those with AIH. Histologic features favoring AIH and DILI based on the models are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Histologic features favoring AIH vs. DILI

| Histologic Features | Favoring | |

|---|---|---|

| AIH | DILI | |

| Severe portal inflammation (≥ grade 2) | * | |

| Prominent intra-acinar lymphocytes | *h | |

| Prominent intra-acinar eosinophils | * | |

| Cholestasis-canalicular | *h, *c | |

| Prominent portal-plasma cells | * | |

| Rosette formation | * | |

| Any levels of fibrosis (≥ grade 1) | * | |

| Prominent port-neutrophils | *c | |

| Hepatocellular cholestasis | *c | |

| Severer focal necrosis (≥ grade 4) | * | |

*h: DILI(HC);

*c: DILI(CS)

Given the observed concordance rate between histologic and clinical diagnosis (65%) and the complete agreement rate among the pathologists (46%), diagnostic models (AUROC of 0.90 to 0.91 in this study) may be beneficial in the clinicopathologic diagnosis of AIH vs. DILI by providing objective probabilities for each condition based on the combinations of histologic features.

We identified no histologic features discriminating AIH vs. DI-AIH in the small subgroup analysis. Previous larger studies that compared AIH vs. DI-AIH reported that histologic findings in AIH and DI-AIH were similar.1, 15 However, it still might be possible that detailed standardized histologic evaluation using a larger cohort of DI-AIH vs. AIH can identify histologic features that can be helpful in the differential diagnosis. Interestingly, in the previous study, cirrhosis was observed in 21% of AIH cases while no cirrhosis was present among DI-AIH cases.1 Our findings were consistent with this, in that advanced fibrosis (i.e., marked bridging fibrosis) was observed only among AIH cases, but not DI-AIH. As observed in our study, histologic diagnosis of DI-AIH vs. AIH is particularly difficult; the concordance rate with clinical diagnosis was 28.6% (vs. 65% in overall cohort) and the complete agreement rate among the pathologists was also 28.6% (vs. 46% in overall cohort and 50% in non-autoimmune DILI). As a correct diagnosis of DILI-AIH is essential for proper clinical decision making,1 we would suggest that the histology of DI-AIH should continue to be systematically evaluated in order to indentify characteristics that distinguish DI-AIH from AIH.

Our findings suggest that different inflammatory cells may be enhanced in DILI vs. AIH cases; prominent portal neutrophil infiltrate was favoring for DILI(CS) while prominent intra-acinar eosinophil infiltrate and prominent portal plasma cell infiltrate were favoring for AIH. Implication and underlying mechanisms of these findings remain unknown. It is intriguing to note that different subsets of lymphocytes and chemokines are involved in eosinophil and plasma cell vs. neutrophil recruitment (Th2 response vs. Th17 response).16, 17 Further studies are warranted to investigate differential cytokine/chemokine profiles in AIH vs. DILI.

Our study has limitations. First, our sample size was rather small and its statistical power was not sufficient in the subgroup analysis. Because we were primarily interested in the histological changes, we did not evaluate interobserver variation on each histologic feature. Second, there is a possibility that some of the observed histologic features may have been influenced by a set of the drugs incriminated in the included DILI cases and/or clinical presentation of AIH (acute vs. chronic presentation). Lastly, our preliminary modeling efforts were only based on statistical results of this small sample without cross-validation.

In summary, this study showed that no single feature was indicative of AIH or DILI, but rather the combination of distinct findings, such as the types of inflammatory cells in different areas, severity of injury/inflammation, and presence of cholestasis, was very helpful in differentiating DILI vs. AIH. The fact that there was more concordance than discordance between clinical and histologic diagnoses suggests that the pathologists were already using the pattern of injury to direct their diagnosis. Further investigation is warranted to validate our findings and to best incorporate the knowledge into current clinicopathologic diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Spanish DILI Registry is supported, in part, by research grants from the Agencia Española del Medicamento and Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (PS 09/01384). This research was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute. On behalf of the Spanish Group for the Study of Drug-Induced Liver Disease, we would like to thank the following participating clinical centres: Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga (centro coordinador): R.J. Andrade, M.I. Lucena, M. García-Cortés, C Stephens, M. Robles-Diaz, A. Fernandez-Castañer, Y. Borraz, E. Ulzurrun, B. Garcia-Muñoz, I. Moreno, L Vicioso; Hospital Torrecárdenas, Almería: M.C. Fernández, G. Peláez, M D Muñoz Sánchez-Reyes, R. Daza, M. Casado, J.L. Vega, F. Suárez, M. Torres, M. González-Sánchez; Hospital de Mendaro, Guipuzkoa: A. Castiella, E.M. Zapata; Hospital de Basurto, Bilbao: P. Martínez-Odriozola; Hospital de Sagunto, Valencia: J. Primo; Hospital de Laredo, Cantabria: M. Carrascosa.

Abbreviations

- DILI

drug-induced liver injury

- AIH

autoimmune hepatitis

- DI-AIH

drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ROC

receiver operating characteristics

- AUC

area under the curve

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Authors do not have conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bjornsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, Kamath PS, Takahashi N, Sanderson S, Neuhauser M, Lindor K. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2040–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.23588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu ZX, Kaplowitz N. Immune-mediated drug-induced liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:755–74. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uetrecht J. Immunoallergic drug-induced liver injury in humans. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:383–92. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abboud G, Kaplowitz N. Drug-induced liver injury. Drug Saf. 2007;30:277–94. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirk AP, Jain S, Pocock S, Thomas HC, Sherlock S. Late results of the Royal Free Hospital prospective controlled trial of prednisolone therapy in hepatitis B surface antigen negative chronic active hepatitis. Gut. 1980;21:78–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milkiewicz P, Hubscher SG, Skiba G, Hathaway M, Elias E. Recurrence of autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68:253–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199907270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soloway RD, Summerskill WH, Baggenstoss AH, Geall MG, Gitnick GL, Elveback IR, Schoenfield LJ. Clinical, biochemical, and histological remission of severe chronic active liver disease: a controlled study of treatments and early prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1972;63:820–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleiner DE. The pathology of drug-induced liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:364–72. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czaja AJ. Autoimmune hepatitis. In: McSween R, editor. Pathology of the liver. Churchill Livingstone; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dienes HP, Erberich H, Dries V, Schirmacher P, Lohse A. Autoimmune hepatitis and overlap syndromes. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:349–62. vi. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Pares A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H, Bianchi FB, Shibata M, Schramm C, Eisenmann de Torres B, Galle PR, McFarlane I, Dienes HP, Lohse AW. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benichou C. Criteria of drug-induced liver disorders. Report of an international consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 1990;11:272–6. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90124-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ, Donaldson PT, Eddleston AL, Fainboim L, Heathcote J, Homberg JC, Hoofnagle JH, Kakumu S, Krawitt EL, Mackay IR, MacSween RN, Maddrey WC, Manns MP, McFarlane IG, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Zeniya M, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–38. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–9. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heurgué AB-CB, Diebold M, Vitry F, Louvet H, Geoffroy P. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: a frequent disorder. Gut. 2007;56(Suppl III):A271. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammerich L, Heymann F, Tacke F. Role of IL-17 and Th17 cells in liver diseases. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011:345803. doi: 10.1155/2011/345803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oo YH, Adams DH. The role of chemokines in the recruitment of lymphocytes to the liver. J Autoimmun. 2010;34:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.