Abstract

Research suggests that perievent panic attacks – panic attacks in temporal proximity to traumatic events – are predictive of later mental health status, including the onset of depression. Using a community sample of New York City residents interviewed 1 year and 2 years after the World Trade Center Disaster, we estimated a structural equation model (SEM) using pre-disaster psychological status and post-disaster life events, together with psychosocial resources, to assess the relationship between perievent panic and later onset depression. Bivariate results revealed a significant association between perievent panic and both year-1 and year-2 depression. Results for the SEM, however, showed that perievent panic was predictive of year-1 depression, but not year-2 depression, once potential confounders were controlled. Year-2 stressors and year-2 psychosocial resources were the best predictors of year-2 depression onset. Pre-disaster psychological problems were directly implicated in year-1 depression, but not year-2 depression. We conclude that a conceptual model that includes pre- and post-disaster variables best explains the complex causal pathways between psychological status, stressor exposure, perievent panic attacks, and depression onset two years after the World Trade Center attacks.

Keywords: Perievent Panic Attack, Depression, Stress Process, Structural Equation Modeling, World Trade Center Disaster

A consistent finding in research related to traumatic events and mental health has been that social factors often influence one's mental health status following such events (Aneshensel, 2009). Thus, a person's gender, race, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, and other social factors have been implicated in both exposure to traumatic events and vulnerability to psychological problems following such events (Kessler, Chiu, Jin, Rusecio, Shear, & Walters, 2006; Thoits, 1995). Research has also shown that pre-existing psychopathology can be exacerbated by exposure to traumatic events and contribute to mental health problems following such exposures (Norris, Friedman, Watson, Byrne, Diaz, & Kaniasty, 2002; Rubonis, & Bickman, 1991).

In the current study, we assessed both psychosocial factors and pre-existing psychological problems to examine the relationships between exposure to the World Trade Center Disaster (WTCD), perievent panic attacks, and depression onset. We focus on panic attacks and depression because research suggests that having a history of panic attacks predicts future mental health disorders (Baillie & Rapee, 2005; Goodwin & Hamilton, 2002a; 2002b; Kessler et al., 2006; Lawyer, Resnick, Galea, Ahern, Kilpatrick, & Vlahov, 2006; Nandi, Tracy, Beard, Vlahov, & Galea, 2009; Nixon, Resick & Griffin, 2004; Person, Tracy, & Galea, 2006). Understanding the association between trauma exposure, perievent panic attacks, and the onset of psychological disorders, such as major depression, could be informative for treatment interventions.

Insight on panic attacks is also important because this may provide a conceptual linkage between pre-existing mental health disorders, psychosocial factors, and exposure to traumatic events, to the later onset of mental health problems (Adams & Boscarino, 2011). Some research suggests that perievent panic (PEP) attacks, that is, panic attacks in temporal proximity to traumatic exposures, have prognostic value for future mental health status (Goodwin, Brook, & Cohen, 2005; Goodwin & Hamilton, 2002; Lawyer et al., 2006). Conceptually, psychosocial factors may be connected to WTCD-related events and PEP, which in turn influence later mental health status. Exposure to traumatic events may also affect underlying psychopathology, increasing the probability of PEP and future mental health disorders.

To further investigate the linkage between PEP and psychological status, we examined depression among New York City (NYC) adults 1 year and 2 years after the disaster. The terrorist attacks in New York City on September 11, 2001, resulted in approximately 2,800 persons killed, thousands injured, and many more residents directly witnessing these events (Boscarino et al., 2004, Centers for Disease Control, 2002; Galea, Ahren, Resnick, Kilpatrick, Bucuvalas, Gold, & Vlahov, 2002).

Some of our earlier work on the WTCD suggests that PEP may be indirectly implicated in poor psychological status, particularly PTSD, in the post-trauma period via its association with later stressful events and social psychological resource loss (Adams & Boscarino, 2011; Boscarino & Adams, 2009). That is, PEP may function to lower self-esteem or social support, which in turn results in poorer mental health outcomes (e.g., persistent anxiety that depletes available social support and/or lowers their self-esteem). PEP may also lead to other negative life events or traumas in the post-disaster period, which again can increase depression. Several investigators note that a post-disaster environment can be a period characterized by the loss of social support, legal problems, property loss, as well as decreases in psychological resources (Adams et al., 2006; Hobfoll, 1989; Norris et al., 2004). Perievent panic may also reflect fundamental psychopathologies that are exacerbated by exposure to a traumatic event. Our previous work suggests that pre-WTCD psychological problems influence PTSD 1 year post-WTCD, but not 2 years afterwards (Adams & Boscarino, 2011).

Given the complex interrelationship between psychological and social factors, in the current study, we use structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess three research questions. First, is PEP related to depression 1 year and 2 years after the WTCD, after controlling for key pre- and post-disaster factors? Second, do socioeconomic factors such, as gender and income, increase the likelihood of exposure to the WTCD and experiencing PEP, or do pre-existing psychopathology explain post-disaster PEP? Third, are pre-existing conditions, socioeconomic factors, and PEP associated with increased post-disaster stressful events and/or lower psychosocial resources, which subsequently influence year-2 depression onset?

METHOD

Study Population

The data for our study come from a prospective cohort study of adults living in New York City on the day of the terrorist attacks against the World Trade Center (September 11, 2001). Using random digit-dialing, we conducted a baseline survey 1 year after the attacks (October-December, 2002). A follow-up survey was conducted 1-year later (October 2003-February 2004). Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish. For the baseline, 2,368 individuals completed the survey. We were able to re-interview 1,681 of these respondents in the follow-up survey. As part of the overall study design, residents who reported receiving mental health treatment a year after the attacks were over-sampled by use of screener questions at the beginning of the survey. The baseline population was also stratified by the 5 NYC boroughs and gender, and was sampled proportionately. Questionnaires were translated into Spanish and then back-translated by bilingual Americans to ensure linguistic and cultural appropriateness. Using standard survey definitions, the baseline cooperation rate was 63% (American Association for Public Opinion Research 2008), and the re-interview rate was 71% (Adams et al., 2006), consistent with previous investigations (Galea et al., 2002; North et al., 2004).

Sampling weights were developed for each wave to correct for potential selection bias and for the over-sampling of treatment-seeking respondents (Groves, Fowler, Couper, & Lepkowski, 2004). Demographic weights also were used to adjust follow-up data for slight differences in response rates by demographic groups (Kessler, Little, & Groves, 1995). With these survey adjustments, our study is representative of adults living in NYC on the day of the WTCD (Adams & Boscarino, 2005; Adams et al., 2006). Additional details on these data are available elsewhere (Boscarino & Adams, 2008). The Geisinger Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB; Danville, PA) currently serves as the IRB of record for this study.

Endogenous Variables

For year-1 and year-2 depression, we used a version of the SCID's major depressive disorder scale from the non–patients version (Spitzer, Williams, & Gibbon 1987), which also has been used in telephone–based population surveys (Galea et al. 2002; Kilpatrick et al. 2003). To conform to SEM analysis requirements, we focused on the 10 specific depression symptoms in this scale experienced during the previous 12 months. For each symptom, respondents had to indicate if that symptom lasted at least two weeks or longer. We used these 10 binary indicators of depression to measure latent depression variables 1-year and 2-years after the WTCD. Data related to the validity of these depression items were previously discussed (Boscarino, Adams & Figley 2004). Following DSM–IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), 10.9% (weighted) of the sample met criteria for depression at year-1, while 11.6% (weighted) met criteria for depression at year-2.

Our study assessed whether respondents met criteria for a perievent panic attack during the World Trade Center Disaster based on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) nomenclature (Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, Compton, North, Rourke, 1999) and we used this measure as an observed variable in our SEM. For our PEP measure, questions were phrased to assess panic symptoms that occurred during or shortly after the World Trade Center Disaster (Galea et al., 2002). The presence of 4+ symptoms classified the respondent as having a perievent panic attack, if these symptoms reached their peak within 10 minutes of onset (Galea et al., 2002). This measure has been used and validated in previous studies (Adams & Boscarino, 2005; Boscarino & Adams, 2009; Boscarino et al. 2004; Galea et al., 2002).

Our SEM model included an observed variable measuring exposure to the World Trade Center Disaster events which could affect depression onset. This construct was assessed during the year-1 survey and consisted of 12 possible events that the respondent could have experienced during or as a consequence of the terrorist attack (e.g., was at the disaster site during attack, lost family members/friends in the attack, etc.). Due to the positively skewed distribution of this variable, we recoded the number of exposures greater than 7 to 6 (range = 0-6). This measure was validated and discussed in detail elsewhere (Boscarino et al., 2004; Boscarino & Adams, 2008).

For SEM analyses, we also developed a latent post-disaster stressor variable using two observed measures. First, the year-2 negative life events scale (Freedy, Kilpatrick & Resnick, 1993) was the sum of 8 negative experiences that could have occurred in the 12 months prior to the follow-up survey (e.g., divorce, death of spouse, etc.). Due to the positive skewedness of this scale, we recoded values 4+ to a value of 3 (range = 0-3). Second, the year-2 traumatic events scale (Freedy et al., 1993), was the sum of 10 traumas that could have occurred in the 12 months prior to the follow-up survey (e.g., forced sexual contact, being attacked with a weapon.). Since this variable was also positively skewed, we recoded values 3+ to the value of 2 (range=0-2). Both of these stressor measures were also validated and discussed in detail elsewhere (Boscarino et al., 2004; Boscarino & Adams, 2008).

We included year-2 social and psychological resources as a latent variable in our SEM analyses, which was composed of two observed measures: Year-2 social support and year-2 self-esteem. Social support was the mean of four questions about emotional, informational, and instrumental support available to the respondent in the previous year (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991), coded low to high social support as a 4-point scale (0-3). In addition, current self-esteem was measured by a version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1979) and consisted of the mean of five items measured on a 5-point scale. Due to the skewed distribution of the scale and the non-whole number scores due to mean substitution for individual items, for SEM analyses we recoded this scale as follows: 1-2.75 = 1; 2.80-3.25 = 2; 3.30-3.75 = 3; 3.80 = 4; 4.0 = 5. Both social support and self-esteem measures were also used and validated in previous studies (Adams & Boscarino, 2005; Boscarino & Adams, 2008; Boscarino et al., 2004).

Exogenous Variables

Our analyses included two observed measures representing demographic status: gender and income. Gender was coded as a binary variable (female = 1 and male = 0). For SEM analyses, annual household income was coded as a 7-point scale (coded 1-7), representing < $20,000 to > $100,000. For those who did not provide income information at baseline, we asked this question at follow-up and substituted these answers for baseline income data. Any remaining missing data on income was coded to mean household income.

To control for pre-disaster mental status, and to assess the respondent's underlying psychopathology, we used two variables: History of pre-disaster depression and history of pre-disaster panic attack. Both of these were based on DSM-IV criteria and were determined based on reported age of onset for these disorders at baseline.

Statistical Analysis

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to answer our research questions due to its advantages in causal analyses of complex data structures. First, SEM is fundamentally a hypothesis testing method (i.e., a confirmatory approach), rather than an exploratory approach (e.g., regression analyses). Second, it allows the simultaneous estimation of a series of regression equations to determine if the proposed model accurately reflects the data. Third, SEM can explicitly estimate measurement error, rather than ignore this issue as is done with traditional techniques. Fourth, SEM allows incorporation of both directly measured variables and unobserved (i.e., latent) ones. Fifth, SEM is uniquely suited to assess both direct and indirect associations among variables, including those between PEP and depression (Byrne 2010; Kline 2005).

In our data analysis, we describe the characteristics of our population (Table 1) and discuss bivariate correlations among the variables in our SEM analysis. We examine all of the variables to confirm that they meet SEM assumptions for both skewedness and kurtosis. Next, we present the results of our SEM: standardized coefficients and goodness-of-fit statistics. As noted, our analysis builds on earlier work (Adams & Boscarino, 2011; Boscarino & Adams, 2009). Descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS, Version 17 (Norusis, 2009). There were no missing data for gender and, as noted, we substituted the mean income for those missing information on this variable. We also did not have missing data on World Trade Center Disaster exposure, mental health status (i.e., pre-disaster panic and depression, perievent panic, year-1 and year-2 depression), or year-2 stressor event (i.e., trauma exposure and negative life events) measures. Finally, there were two cases with missing data on social support and three with missing data on the self-esteem. For both scales, we substituted the mean for the missing data.

Table 1.

Key Study Variables and Baseline Characteristics

| Variables in the Model | Weighted % (Unweighted N)† |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 46.2 (693) |

| Female | 53.8 (988) |

| Income | |

| <$40,000 | 44.7 (784) |

| $40,000-$99,999 | 39.2 (650) |

| $100,000+ | 16.1 (247) |

| Stressful Events | |

| Exposure World Trade Center Disaster | |

| Low (0-1 Event) | 26.7 (362) |

| Moderate (2-3 Events) | 43.9 (719) |

| High (4-5 Events) | 21.8 (416) |

| Very High (6+) | 7.6 (184) |

| Year-2 Negative Life Events Past Year | |

| None | 63.3 (991) |

| One Event | 24.7 (429) |

| Two or more Events | 12.0 (261) |

| Year-2 Traumatic Events Past year | |

| None | 85.0 (1390) |

| One Event | 9.3 (175) |

| Two or more Events | 5.7 (116) |

| Psychosocial Resources | |

| Year-2 Self-Esteem Past Year | |

| Low | 25.2 (471) |

| Moderate | 34.8 (569) |

| High | 40.0 (641) |

| Year-2 Social Support Past Year | |

| Low | 35.7 (596) |

| Moderate | 37.9 (656) |

| High | 26.4 (429) |

| Pre-Disaster Psychological Health | |

| Lifetime Depression Pre-disaster | |

| No | 87.0 (1366) |

| Yes | 13.0 (315) |

| Lifetime Panic Disorder Pre-Disaster | |

| No | 88.0 (1444) |

| Yes | 12.0 (237) |

| Post-Disaster Psychological Health | |

| Perievent Panic Attack | |

| No | 89.7 (1451) |

| Yes | 10.3 (230) |

| Year-1 Depression past 12 Months* | |

| No | 89.1 (1409) |

| Yes | 10.9 (272) |

| Year-2 Depression past 12 Months* | |

| No | 88.4 (1404) |

| Yes | 11.6 (277) |

All percentages are weighted and all n's are unweighted.

Assessed based on full DSM-IV criteria.

Estimates for our SEM model were calculated using AMOS, Version 17.0 (Arbuckle, 2008), with maximum likelihood estimation methods. Our input data were a weighted correlation matrix for all of the variables in the model, using the survey weights discussed above. We began our model building by allowing the error term for each symptom from the year-1 depression measure to correlate with its year-2 counterpart. For assessment of SEM model fit, we used the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Bentler-Bonett normed fit index (NFI), and comparative fit index (CFI) (Arbuckle, 2008). Generally, a CFI and NFI greater than .90 and a RMSEA less than .10 indicate adequate model fit (Bryne 2010; Kline 2005). Significant p values were <.05, based on two-tailed tests.

RESULTS

As can be seen in Table 1, about 54% of study respondents were women. In addition, 13% of residents had a history of pre-disaster depression and 12% had a history of pre-disaster panic attacks. Over 10% met the DSM-IV criteria for a perievent panic attack, while 11% met criteria for year-1 depression and 12% met criteria for year-2 depression.

Bivariate Pearson's correlation coefficients among the observed variables in the SEM model were calculated (available upon request). Briefly, PEP was associated with all of the depression symptoms for both year-1 (rs ranging from .16 to .22, all ps<.001) and year-2 (rs ranging from .09 to .21, all ps <.001). PEP was also associated with WTCD exposure (r =.20, p < .001), year-2 negative life events (r =.16, p<.001), year-2 traumas (r =.09, p<.001), year-2 self-esteem (r = -.16, p<.001), and year-2 social support (r = -.10, p<.001). Finally, higher exposure to WTCD events was associated with all of the year-1 and year-2 depression items (all ps < .001), as well as year-2 negative life events (r =.16, p<.001), traumas (r =.09, p<.001), and self-esteem (r = -.08, p<.001), but not social support (r = -.01, p>.05).

Although these correlations are suggestive, due to confounding, the longer-term direct impact of PEP on mental health status cannot be inferred from these data. Therefore, we assessed the direct effects of PEP on year-1 and year-2 depression measured as latent constructs, controlling for other factors. As described, we initially allowed the error terms for each year-1 depression symptom to correlate with its year-2 counterpart. All of the exogenous variables (i.e., demographic and pre-disaster mental health measures) were allowed to correlate with each other. We also allowed all of these measures to have direct effects on all of the endogenous variables (e.g., income on exposure, PEP, stressor events, psychosocial resources, year-1 depression, and year-2 depression). The model specified direct effects between all year-1 endogenous and year-2 endogenous variables (e.g., PEP on year-2 stressor events, year-2 psychosocial resources, year-1 and -2 depression) and contained 4 observed exogenous variables, 26 observed endogenous variables, 4 unobserved endogenous variables, and 30 unobserved exogenous variables, for a total of 64 variables. The model also estimated 16 covariances and 34 variances. With 465 distinct sample moments and 108 parameter estimates, the model had a χ2 = 2229.94 (df = 357, p < .001). Other indices suggested that our model could be improved, with a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .056 (90% CI = .054 - .058), Bentler-Bonett normed fit index (NFI) = .921, and comparative fit index (CFI) = .933. To increase the model's parsimony and reduce the possibility that we over controlled with the pre-disaster panic mental health measure, we eliminated non-significant direct pathways for this measure. We eliminated correlations between the four exogenous variables (e.g., gender and income) that were not significant. Finally, we examined the modification indices and allowed error terms for several of the depression indicators to correlate. After these changes, we recalculated all parameter estimates. The new model contained 465 distinct sample moments, 107 parameter estimates, and a χ2 = 1402.23 (df = 358, p<.001). Based on the fit statistics, this second specified model adequately fit the data, with a RMSEA = .042 (90% CI = .039 - .044), NFI = .950, and CFI = .962.

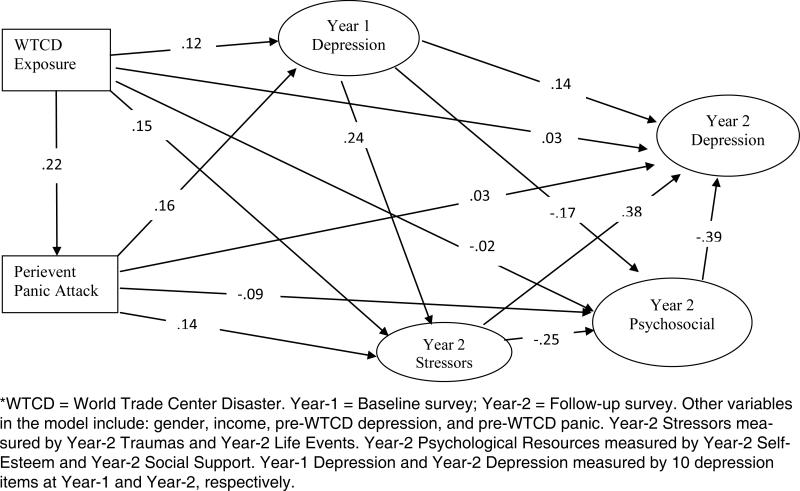

Figure 1 presents a simplified depiction of the final structural model with standardized coefficients, indicating significant direct paths, and omitting correlated error terms. (A complete final SEM model is available from the corresponding author.) As can be seen in Figure 1 and Table 2, World Trade Center Disaster exposure increases the likelihood of a PEP, year-1 depression, and year-2 stressor events (β = .22, p < .001). PEP is directly related to year-1 depression (β = .16, p < .001), but not to year-2 depression (e.g., β = .03, p = .189). It also increases year-2 stressor events (β = .14, p<.001) and lowers year-2 psychological resources (β = -.09, p = .007). Year-1 depression is positively related to greater year-2 stressor events (β = .24, p < .001), negatively related to year-2 psychological resources (β = -.17, p < .001), and positively related to year-2 depression (β = .14, p < .001). As expected, both year-2 stressor events and year-2 psychosocial resources are associated with year-2 depression (β = .38 and -.39, respectively, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Simplified Depiction of Final Structural Equation Model for Perievent Panic and Major Depression (N=1681)*

Table 2.

Structural Equation Model – Unstandardized Coefficients and Standardized Coefficients for Direct Effects Linking Demographic, Pre-WTCD Mental Health, WTCD Exposure, Perievent Panic, Stressful Events, Psychosocial Resources, and Depression (N=1,681)

| Variables in the Model | WTCD Exposure | Perievent Panic | Year-1 Depression | Year-2 Stressor Events | Year-2 Psychosocial Resources | Year-2 Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (s.e.) Beta | b (s.e.) Beta | b (s.e.) Beta | b (s.e.) Beta | b (s.e.) Beta | b (s.e.) Beta | |

| Gender | -0.098 (.064) -.037ns | 0.046 (.014) .075** | 0.016 (.012) .030ns | 0.070 (.036) .064ns | 0.051 (.023) .072* | -0.003 (.013) -.006ns |

| Year-1 Income | 0.066 (.015) .107*** | -0.018 (.003) -.122*** | -0.009 (.003) -.074*** | 0.010 (.009) .037ns | 0.072 (.007) .428*** | 0.008 (.005) .061ns |

| Year-1 Lifetime Depression Pre-WTCD | 0.331 (.094) .085*** | 0.059 (.022) .065** | 0.322 (.018) .403*** | 0.139 (.056) .086* | -0.116 (.037) -.112*** | -- |

| Year-1 Lifetime Panic Disorder Pre-WTCD | -- | 0.064 (.022) .068** | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Year-1 WTCD Exposure | -- | 0.050 (.006) .216*** | 0.024 (.005) .115*** | 0.064 (.014) .154*** | -0.004 (.009) -.015ns | 0.007 (.005) .033ns |

| Year-1 Perievent Panic | -- | -- | 0.144 (.020) .163*** | 0.242 (.061) .135*** | -0.107 (.040) -.093** | 0.030 (.023) .033ns |

| Year-1 Depression | -- | -- | -- | 0.496 (.078) .244*** | -0.222 (.054) -.169*** | 0.145 (.031) .140*** |

| Year-2 Stressor Events | -- | -- | -- | -- | -0.162 (.039) -.251*** | 0.193 (.031) .380*** |

| Year-2 Psychosocial Resources | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -0.307 (.047) -.389*** |

| R2 = | 0.022 | 0.074 | 0.235 | 0.174 | 0.374 | 0.501 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001, two-tailed t-test

WTCD = World Trade Center Disaster; ns = not significant; s.e. = standard error.

Further examination of variables in the model (Table 2) shows that both income and pre-disaster depression were associated with greater exposure to the World Trade Center Disaster (p < .001). For PEP, income lowered the likelihood of this outcome (p < .001), while being female, having pre-disaster depression or panic, and greater exposure to the WTCD increased the likelihood of this psychological problem (p = .002, .006, .004, .001, respectively). Income and a history of depression were related to year-1 depression (ps < .001, for both associations), with income negatively related to this endogenous variable. Of the demographic or pre-disaster variables, only pre-WTCD depression was related to year-2 stressor events (β = .086, p=.013). Being female (β = .072, p=.025) and having a higher income (β = .428, p<.001) increased year-2 psychological resources, while pre-disaster depression decreased these resources (β = -.112, p = .001). Finally, none of the demographics or pre-disaster mental health measures was associated with year-2 depression.

Mediation is suggested when an independent variable has an association with a dependent variable and the association between them is significantly reduced after the mediated variable is included in the model. For this study, we only discuss the direct, indirect, and total effects of PEP on year-2 depression, as mediated by year-1 depression, year-2 stressor events, and year-2 psychological resources. The standardized total effect of PEP on year-2 depression is .19, which means that the indirect or mediated effect of this variable on year-2 depression is .16 (.19-.03 = .16). More specifically, individuals who meet criteria for PEP have about a .19 standard deviation increase in the probability of having depression two years after the WTCD. However, that increase is almost entirely due to the fact that those individuals who have a perievent panic attack are also more likely to suffer from year-1 depression, experience more stressor events between year-1 and year-2 post-disaster, and have fewer psychosocial resources two years post-disaster.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we focused on several research questions: First, does perievent panic predict later depression onset after trauma exposure? Second, do pre-existing mental health problems and demographic factors predict traumatic event exposure, PEP, psychosocial resources, and depression? Third, are pre-existing factors and PEP associated with increased post-disaster stressful events and/or lower psychosocial resources, which influence year-2 depression onset? The answer to the first question, related to PEP predicting post-trauma depression, as with our previous work on PTSD and PEP (Adams & Boscarino, 2011; Boscarino & Adams 2009), is no. PEP had no direct effect on later depression onset, once other factors are included in the analytic model. Perievent panic's influence on later depression is almost completely indirect via current depression and later negative life events and psychosocial resources. Thus, there continues to be little evidence that perievent panic directly predicts later mental health status among trauma survivors.

As for the second research question, our SEM model did show that both pre-existing mental health problems and demographic factors affect specific endogenous variables. That is, income and pre-WTCD depression were associated with a person's exposure to the WTCD and all 4 of the pre-WTCD mental health and demographic measures assessed are related to perievent panic (Table 2). Women are more likely to have a PEP attack and the wealthy less likely, while those with pre-WTCD depression or pre-WTCD panic disorder are more likely to have a PEP attack. The predictive value of both demographic and pre-WTCD mental health variables are also revealed for Year-1 depression, Year-2 stressor events, and year-2 psychological resources (Table 2). It is worth noting that unlike most research on stressful events (Thoits 1995), in our study those with higher income reported greater exposure to the WTCD, rather than less, likely an artifact of an attack focused on New York City's financial community.

The interconnection of individual psychological problems within the larger post-disaster context is often discovered in studies of disasters (e.g., Adams & Boscarino, 2005; Adams, Bromet, Panina, Golovakha, Goldgaber, et al., 2002; Adeola, 2009). The same is true when examining who is most likely to experience a traumatic event (Aneshensel, 2009; Link & Phelan, 1995). Related to our third research question, the answer is yes: findings suggest a sequence of events with demographic factors and pre-trauma mental health factors influencing exposure to a traumatic event, and all of these factors increasing the likelihood of PEP onset, which is associated with lower psychosocial resources and increases in stressor events, leading to later depression onset. These results support Hobfoll's conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989) and the stress proliferation theory (Pearlin, Aneshensel, & Leblanc 1997), in that an initial stressful event (i.e., WTCD) leads to a host of other psychological and interpersonal problems, which proliferate into other areas of life.

This study's conclusions need to be seen in light of its strengths and limitations. A major strength was that our study involved a large-scale random survey among a multi-ethnic urban population. We also assessed a range of psychological and interpersonal measures over a 2-year period using standardized instruments. We also attempted to capture features of our sample that reflect pre-WTCD mental health problems. Finally, we used SEM to examine the multiple pathways in which trauma, psychological resources, and mental health status interrelate.

Potential study limitations include omitting individuals without a telephone, those who were institutionalized, and those who did not speak either English or Spanish. Given that our study's final completion rate was lower than desired, non-response bias also could be an issue affecting our results. However, our weighted data closely matched census data for New York City. We also conducted our study among a population experiencing multiple terrorism events (e.g., the 2001 anthrax scare), which may have affected our results (Boscarino, Adams, Figley, Galea, & Foa, 2006). A further limitation was that several of our measures did not cover the exact same timeframe. Our year-2 measure of social support, for example, covers the year prior to the survey, while our other year-2 psychological resource variable is for “current” self-esteem. Finally, as with most disaster studies, we did not have any pre-disaster measures of mental health status. We did include several retrospective indicators of pre-WTCD panic and depression based on age of onset, but these variables may suffer from recall bias.

Despite these limitations, our study suggests that while PEP seems to have a direct association with post-disaster stressor events and psychosocial resources, it does not have a direct effect on longer-term (i.e., year-2) depression, once other factors are taken into account. PEP does have shorter-term effects on depression, which has consequences for stressor events, psychosocial resources, and long-term depression. These findings are consistent with our earlier PTSD results – the ultimate dependent variable following traumatic exposures (Adams & Boscarino, 2011). Given the results from both of these studies, the predictive value of PEP appears to be clearly limited as an indicator for interventions directed at long-term mental health status. The best predictors for both year-2 PTSD and depression were year-1 PTSD, year-2 stressor events, and year-2 psychosocial resource variables. While PEP may have shorter-term mental health consequences, our findings suggest that interventions focused on improving psychosocial resources and reducing stressor events in the post-trauma period may be more beneficial in reducing longer-term mental health problems. The results also support our hypothesis that both epidemiological and psychosocial perspectives are important in examining the long-term consequences of major community disasters.

Contributor Information

Richard E. Adams, Department of Sociology, Kent State University, Kent, OH..

Joseph A. Boscarino, Center for Health Research, Geisinger Clinic, 100 N. Academy Avenue, Danville, PA 17822-4400.

REfERENCES

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA. Stress and well-being in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attack: The continuing effects of a community-wide disaster. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33:175–190. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA. A structural equation model of perievent panic and posttraumatic stress disorder after a community disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:61–69. doi: 10.1002/jts.20603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA, Galea S. Social and psychological resources and health outcomes after World Trade Center disaster. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Bromet EJ, Panina N, Golovakha E, Goldgaber D, Gluzman S. Stress and well-being after the Chornobyl nuclear power plant accident. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:143–156. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeola FO. Mental health and psychological distress sequelae of Katrina: An empirical study of survivors. Human Ecology Review. 2009;16:195–210. [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research . Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcomes rates for surveys. American Association for Public Opinion Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition Text Revision American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS. Toward explaining mental health disparities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:377–394. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 17.0 user's guide. SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baillie AJ, Rapee RM. Panic attacks as risk markers for mental disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40:240–244. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0892-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA. Psychobiologic predictors of disease mortality after psychological trauma: Implications for research and clinical surveillance. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196:100–107. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318162a9f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA, Adams RE. Overview of findings from the World Trade Center Disaster Outcome Study: Recommendations for future research after exposure to psychological trauma. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health. 2008;10:275–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA, Adams RE. Peritraumatic panic attacks and health outcomes two years after psychological trauma: Implications for intervention and research. Psychiatry Research. 2009;167:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA, Adams RE, Figley CR, Galea S, Foa EB. Fear of terorism and preparedness in New York City 2 years after the attacks; Implications for disaster planning and research. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2006;12(6):505–513. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200611000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. 2nd ed. Routledge; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Deaths in World Trade Center terrorist attacks—New York City, 2001. Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report. 2002;51(Special Issue):16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedy JR, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. Natural disasters and mental health: Theory, assessment, and intervention. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1993;8:49–103. [Special issue: Handbook of Post-disaster Interventions].

- Galea S, Ahren J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Vlahov D. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England of Medicine. 2002;346:982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Brook JS, Cohen P. Panic attack and the risk of personality disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:227–235. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Hamilton SP. The early onset fearful panic attack as a predictor of severe psychopathology. Psychiatry Research. 2002;109:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM. Survey methodology. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, Norris FH. Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: Sequential roles of social causation and social selection. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:274–281. doi: 10.1002/jts.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Jin R, Ruscio AM, Shear K, Walters EE. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:415–424. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Little RJ, Groves RM. Advances in strategies for minimizing and adjusting for survey non-response. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1995;17:192–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RE. Principle and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Resnick HS, Galea S, Ahern J, Kilpatrick DG, Vlahov D. Predictors of peritraumatic reactions and PTSD following the September 11th terrorist attacks. Psychiatry. 2006;69:130–141. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2006.69.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35(Extra Issue):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A, Tracy M, Beard JR, Vlahov D, Galea S. Patterns and predictors of trajectories of depression after an urban disaster. Annals of Epidemiology. 2009;19:761–770. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RD, Resick PA, Griffin MG. Panic following trauma: The etiology of acute posttraumatic arousal. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18:193–210. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00290-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981-2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Pfefferbaum B, Tivis L, Kawasaki A, Reddy C, Spitznagel EL. The course of posttraumatic stress disorder in a follow-up study of survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;16:209–215. doi: 10.1080/10401230490522034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norusis M. SPSS 17.0 Guide to data analysis. Prentice Hall; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Aneshensel CS, Leblanc AJ. The forms and mechanisms of stress proliferation: The case of AIDS caregivers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:223–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person C, Tracy M, Galea S. Risk factors for depression after a disaster. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:659–666. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000235758.24586.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picou JS, Marshall BK, Gill DA. Disaster, litigation and the corrosive community. Social Forces. 2004;82:1493–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler LB, Bucholz KK, Compton WM, North CS, Rourke KM. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry; St. Louis, MO: 1999. [January 9, 2002]. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rubonis AV, Bickman L. Psychological impairment in the wake of disaster: The disaster-psychopathology relationship. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:384–399. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. Stress, coping and social support processes: Where are we? What Next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35(Extra Issue):53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA. The epidemiology of social stress. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;60:104–125. [Google Scholar]