Abstract

We here introduce a fixed-pressure model of hemorrhagic shock in rats that maximizes effects on mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) during shock and yet maintains high reproducibility and controllability. The MAP of rats was adjusted to 25 to 30 mm Hg by blood withdrawals during 30 min. After a shock period of 60 min, rats were resuscitated either with lactated Ringer solution (LR) only or with the collected blood 3-fold diluted with LR (LR + blood) and monitored for further 150 min. Throughout the experiment, vital parameters and plasma marker enzyme activities and creatinine concentration were assessed. Thereafter, liver, kidneys, small intestine, heart, and lung were harvested and evaluated histopathologically. Vital parameters, plasma marker enzyme activities, creatinine concentration, and histopathology indicated pronounced but reliable and reproducible systemic effects and marked organ damage due to hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. In contrast to rats that received LR + blood, which survived the postresuscitation period, rats receiving LR only invariably died shortly after resuscitation. The hemorrhagic shock model we present here maximally affects MAP and yet is highly reproducible in rats, allowing the study of various aspects of hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation under clinically relevant conditions.

Abbreviations: ACDA, acid citrate dextrose solution A; LR, lactated Ringer solution; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure

Hemorrhagic shock results from a life-threatening loss of blood and leads to tissue ischemia and insufficient evacuation of cellular metabolic degradation products. Mortality is linked directly to massive blood loss or occurs indirectly due to secondary multiple organ failure. In particular, loss of gastrointestinal, renal, hepatic, and pulmonary function is frequent after hemorrhagic shock.2,14,18,46

Current guidelines for nonsurgical treatment of hemorrhagic shock recommend rapid volume resuscitation by using crystalloids to restore the intravascular volume.33 However, this practice is controversial because aggressive restoration of intravascular volume with a rapid increase in blood pressure before controlling hemorrhage can lead to increased mortality.20 Consequently, ‘controlled fluid resuscitation’ with small volumes before stopping bleeding has been advocated.4,9 In particular, treating severe hemorrhagic shock that bears the risk of interruption of blood flow to vital organs remains clinically challenging.38 To improve existing strategies in emergency medicine, the characteristics of and possible therapeutic interventions for severe hemorrhagic shock need to be studied in an effective, realistic, and reproducible animal model.

Numerous animal models intended to simulate and study hemorrhagic shock conditions have been established so far.1,6-8,12,16,23,25-30,35,37,45 In view of experimental reproducibility and reliability, fixed-pressure models are superior to fixed-volume approaches. In fixed-pressure animal models, hemorrhagic shock is achieved by withdrawing blood until the desired blood pressure is reached; during the shock period, the blood pressure is held at this value by further blood withdrawal or reinfusion of collected blood or other fluids. The circulating blood volume of mammals does not correlate strictly with body weight due to individual differences in the relation of blood volume to mass of fat and muscle tissue and does not linearly increase with body weight gain (heavier animals usually have more fat and therefore comparatively less blood). Therefore, unlike fixed-pressure models, fixed-volume models (which are based on body weight) yield variable decreases in mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and thus in the intensity of hemorrhagic shock.

In existing fixed-pressure models, either the adjusted MAP remains high (35 mm Hg or above)16,17,28 and thus shock-related tissue injury is rather low or the duration of the shock period is very short8,12,39 or unrealistically long,17,37 thus not reflecting the shock situations of 45 to 60 min typically seen in Western industrialized countries. In other studies using models based on fixed-pressure hemorrhagic shock, substantial variations in MAP are tolerated during shock episodes23 or animals are not resuscitated,37 a practice that is reasonable only for very mild models and that excludes the possibility to study resuscitation regimens for severe hemorrhagic shock.

Considering the advantages and disadvantages of the already existing hemorrhagic shock models in the context of clinical problems and characteristics of most severe hemorrhagic shock, we here describe a fixed-pressure model in rats that involves severe shock, is life-threatening, and is characterized by a well-controlled MAP that is just high enough to reliably ensure survival after a clinically realistic shock period of 60 min and for a reasonable period subsequent to a 30-min resuscitation. Moreover, we minimized artificial influences like heparinization, which we replaced with acid citrate dextrose solution A (ACDA), as is contained in human stored blood. Our new rat model likely is applicable to studies of various resuscitation regimens and potentially beneficial interventions during severe hemorrhagic shock.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and materials.

Formalin solution (10%, buffered) and hematoxylin (51260, Fluka Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), Ringer and lactated Ringer (LR) solutions (Fresenius, Bad Homburg, ketamine (10%, Ceva, Düsseldorf, Germany), lidocaine (xylocaine 1%, AstraZeneca, Wedel, Germany), and ACDA (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) were obtained from commercial sources. Catheters (inner diameter, 0.58 mm; outer diameter, 0.96 mm; Portex, Smiths Medical International, Hythe, UK), neonatal blood filters (200 µm; Impromediform, Lüdenscheid, Germany), paraffin (catalog no. 501006, Paraplast Tissue Embedding Medium, McCormick Scientific, St Louis, MO), surgical suture (Resorba, Nürnberg, Germany), medical oxygen (Air Liquide, Düsseldorf, Germany), and isoflurane (Forene 100%, Wiesbaden, Germany) were obtained from the listed vendors.

Animals.

Male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus; n = 16; weight, 400 to 450 g; age, 12 to 15 wk) were obtained from the Central Animal Unit of Essen University Hospital (Essen, Germany). Animals were kept under standardized conditions of temperature (22 ± 1 °C), humidity (55% ± 5%), and 12:12-h light:dark cycles with free access to food (Ssniff Spezialdiäten, Soest, Germany) and water. All animals received humane care according to the standards of Annex III of the directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.13 The experimental protocol has been approved according to the local animal protection act.

Anesthesia, analgesia, and catheter placement.

Experimental procedures are summarized in Figure 1. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (2% in 100% medical O2 at 1 L/min for induction of anesthesia, 1% to 1.5% throughout the experiment) through face masks connected to a vaporizer (Isofluran Vet Med Vapor, Drägerwerk, Lübeck, Germany) and received ketamine (50 mg/kg SC) into the right chest wall for analgesia; additional ketamine (40 mg/kg SC) was administered as needed (that is, to prevent reappearance of blink and interdigital reflexes) throughout experiments. Lidocaine (5 mg/kg SC) was applied locally prior to creation of a skin-deep incision along the right groin, and catheters were placed within the femoral artery and vein. Thereafter, a skin-deep incision was made along the ventral cervical skin and a catheter placed within the right external jugular vein. All catheters were fixed with surgical suture (silk). At the end of the experimental procedure (that is, after the postresuscitation period), the small intestine, kidneys, liver, lung, and heart were harvested under deep isoflurane anesthesia, and thus the rats were euthanized.

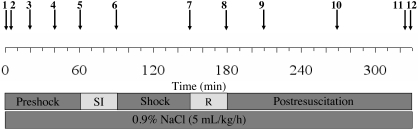

Figure 1.

Schedule of the experimental procedures. 1, Start of anesthesia; 2, analgesia (ketamine, lidocaine); 3, catheter inserted into femoral artery (blood sample 1; start of biomonitoring); 4, all catheters inserted (blood sample 2); 5, start of shock induction (SI); 6, end of shock induction (MAP = 25 to 30 mm Hg; blood sample 3); 7, start of resuscitation (R; blood sample 4); 8, end of resuscitation (blood sample 5); 9, blood sample 6; 10, blood sample 7; 11, blood sample 8; 12, resection of organs (death of rat).

Induction of hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation.

After catheter insertions, rats were allowed to stabilize for 30 min. Hemorrhagic shock was induced by removing 2 mL blood every 3 min through the femoral artery catheter, by using a 2-mL syringe (Terumo, Leuven, Belgium) prefilled with 0.2 mL ACDA solution. Bleeding was continued until the MAP dropped to 25 to 30 mm Hg; this process typically took about 20 min. During the following 10 min, the MAP was ‘fine tuned’ by blood sampling of smaller volumes (0.5 to 1 mL). The blood was stored in sterile plastic conical tubes at 37 °C. For the next 60 min, the MAP remained between 25 to 30 mm Hg, typically without the need of any further intervention. In some individual cases, small amounts (0.1- to 0.5-mL aliquots) of 0.9% NaCl solution had to be administered or additional small blood samples (0.1- to 0.5-mL aliquots) withdrawn, to keep the MAP within the desired range. During the 30 min after the shock episode, group-specific resuscitation fluids were infused into the jugular vein by using a syringe pump (Perfusor-Secura FT; B Braun, Melsungen, Germany). Experiments were continued for 150 min more, unless the rat died earlier. To compensate for fluid loss over surgical areas and respiratory epithelium and to stabilize the blood pressure during the shock period, 0.9% NaCl solution (5 mL/kg/h, 37 °C) was infused through the femoral vein catheter throughout the experiment in all rats studied.

Study groups.

We compared 3 experimental groups. The sham group (n = 4 rats) experienced no shock or resuscitation. The shock LR group (n = 6) was resuscitated with LR solution (37 °C) equal to 3 times the total volume of blood collected. The shock LR + blood group (n = 6) underwent resuscitation by autotransfusion of the collected ACDA-treated blood plus LR at twice the volume of the collected blood. The collected blood was mixed gently with the necessary amount of LR immediately before resuscitation, and the prewarmed (37 °C) blood–LR solution was administered through a neonatal (200-µm) blood filter to exclude microclots, which may have formed during blood storage. Samples of the resuscitation fluid were taken before and after resuscitation and centrifuged (3000 × g for 15 min at 25 °C). The free hemoglobin content and LDH activity of the resulting supernatant was quantified to control for hemolysis.

Biomonitoring.

For close regulation of our model, we monitored several systemic and vital parameters throughout the experimental procedure. Systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure were measured continuously by using the femoral artery catheter, which was connected to a pressure transducer, and displayed on a monitor. Ringer solution was infused at 3 mL/h to keep the catheter functional. Heart rates were determined from systolic blood pressure spikes. The rectal temperature of the rats was monitored continuously by using a rectal sensor and maintained at 37 ± 1 °C by means of an underlying heated operating table and by covering the animal with aluminum foil. The breathing rate per minute was determined according to the number of ventilatory movements in 10-min intervals.

Assessment of blood and plasma parameters.

By using 2-mL syringes (Pico50, Radiometer Medical, Brønshøj, Denmark) containing 80 IU electrolyte-balanced heparin, blood samples (0.7 mL) for blood gas analysis and the assessment of marker enzyme activities were taken from the femoral artery catheter immediately after its insertion, after insertion of all catheters, at the end of shock initiation, immediately before the beginning of resuscitation, and at the end of the resuscitation period and 30, 90, and 150 min thereafter (Figure 1). After each blood sampling, 0.7 mL 0.9% NaCl solution was administered via the femoral artery.

Arterial oxygen and carbon dioxide partial pressures, oxygen saturation, pH, acid–base status, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, electrolytes (Na+, K+, Cl–, Ca2+), metabolic parameters (lactate, glucose), and osmolality were assessed by using a blood gas analyzer (ABL 715, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Blood plasma was obtained by centrifugation (3000 × g for 15 min at 25 °C) and stored at 4 °C until its use (within 4 h). The plasma activities of LDH as a general indicator of cell injury, AST and ALT as indicators of liver injury, and creatine kinase to assess muscle cell injury and the concentration of creatinine as an indicator of kidney injury and function were determined by using a fully automated clinical chemistry analyzer (Vitalab Selectra E; VWR International, Darmstadt, Germany).

Histopathologic evaluation of organs.

Samples of the small intestine (beginning, middle, and end of jejunum), the entire left kidney, the left lobe of the liver, and the entire lung and heart were fixed for 24 to 48 h in formalin (10% neutral buffered). Paraffin-embedded sections (3 µm) were stained with hematoxylin–eosin and histopathologic changes documented photographically.

Control for hemolysis in blood for resuscitation.

The concentration of free hemoglobin within the resuscitation fluid of the shock LR + blood group was assessed to exclude infusion of partially hemolyzed blood. Hemoglobin in the supernatant of the resuscitation fluid was determined from the absorption of the hemoglobin Soret band; to this end, the absorption maximum between 400 and 420 nm was determined spectrophotometrically, with LR serving as a blank. Values were corrected for nonspecific absorption or turbidity at 475 nm. Hemoglobin concentrations (µmol/L) were calculated according to a molar extinction coefficient of ϵ = 131,000 M–1cm−1. Hemolysis also was assessed based on LDH activity. If the concentration of free hemoglobin or the activity of LDH within the resuscitation fluid exceeded the preshock plasma value of the respective rat by 30% or more, the fluid was not used, and the rat was euthanized.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons among multiple groups were performed using one-way ANOVA either for nonrecurring or for repeated measures followed by Fisher least significant difference posthoc analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Blood pressure and other vital parameters.

In the sham group, MAP remained around 100 mm Hg throughout the experiment (Figure 2). In the shock groups, MAP reliably was decreased from 102 ± 5 mm Hg to a stable value of 27 ± 1 mm Hg by the withdrawal of 29.5 ± 1 mL blood/kg during 30 min. In rats receiving LR + blood for resuscitation, the MAP increased to around 90 mm Hg and slightly but nonsignificantly decreased during the remainder of the experiment. In rats of the shock LR group, MAP reached only 50 to 60 mm Hg during resuscitation and immediately dropped to 31 ± 3 mm Hg thereafter; the rats died short time later (Figure 2). The average time of death in this group was 70 ± 20 min subsequent to resuscitation.

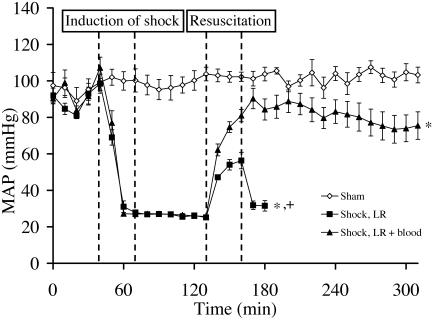

Figure 2.

Effect of severe hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation on mean arterial blood pressure (MAP). Rats experienced hemorrhagic shock for 60 min and then were resuscitated either with lactated Ringer solution (LR) or LR + blood, as shown in Figure 1. Values shown represent the mean ± SEM of 4 rats for the sham group and of 6 rats per shock group. The curve of the LR group ends with the death of the first rat of this group. *, P < 0.05 compared with sham group (since shock induction); +, P < 0.05 compared with shock LR + blood group (since resuscitation).

The heart rate of the sham group animals remained constant around 340 bpm throughout the experiment (Table 1). In the shock animals, heart rate decreased to about 280 bpm during the shock period. Resuscitation with LR + blood increased the heart rate to basal values at the end of the experiment, whereas in the shock LR group, heart rate remained at approximately 300 bpm until death.

Table 1.

Effects of severe hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation on heart rate, breathing rate, and rectal temperature in rats

| Group | Basal | End of shock | End of resuscitation | 2 h after resuscitation | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | |||||

| Sham | 342 ± 4.9 | 336 ± 13.8 | 318 ± 9.3 | 354 ± 14.7 | |

| Shock LR | 351 ± 11.7 | 282 ± 11.2a,b | 300 ± 10.2a | ||

| Shock LR + blood | 345 ± 8.7 | 279 ± 12.5a,b | 309 ± 7.6a | 357 ± 8.8 | |

| No. of respirations per minute | |||||

| Sham | 59 ± 3.0 | 63 ± 3.6 | 66 ± 1.6 | 58 ± 0.9 | |

| Shock LR | 55 ± 3.0 | 59 ± 3.2 | 59 ± 4.8 | ||

| Shock LR + blood | 56 ± 1.5 | 60 ± 1.8 | 75 ± 2.1a,b | 63 ± 4.0 | |

| Rectal temperature (°C) | |||||

| Sham | 36.5 ± 0.1 | 37.2 ± 0.1a | 37.2 ± 0.1a | 37.3 ± 0.1a | |

| Shock LR | 36.8 ± 0.1 | 36.4 ± 0.2b | 36.6 ± 0.2b | ||

| Shock LR + blood | 36.7 ± 0.1 | 36.7 ± 0.1b | 37.0 ± 0.1 | 37.0 ± 0.1 | |

Animals experienced hemorrhagic shock for 60 min and then were resuscitated either with lactated Ringer solution (LR) or LR + blood, as shown in Figure 1. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Basal values were obtained immediately after insertion of the catheter into the femoral artery.

P < 0.05 compared with basal value of the same group.

P < 0.05 compared with value for sham group at the same time point.

Rats in the shock LR + blood group exhibited a significant increase in breathing rates during the resuscitation period. At all other time points, values of both shock groups were not significantly different from those of sham group animals (Table 1).

The rectal temperature of the sham group animals slightly increased during the basal equilibration period and then remained constant throughout the experiment (Table 1). Time-dependent comparisons of these rats with those of both shock groups indicated a decrease in rectal temperature during the shock period and its increase during resuscitation in the shock LR + blood group but not the shock LR rats.

Blood hemoglobin.

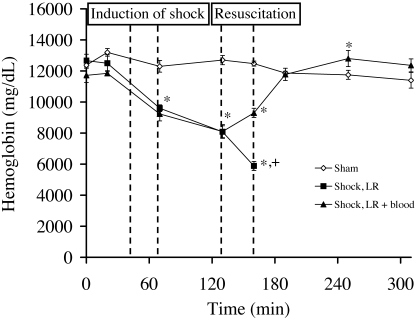

In the sham group animals, blood hemoglobin concentration did not change significantly throughout the experiment (Figure 3). In both shock groups, blood hemoglobin decreased to about 9.5 g/dL at the end of shock induction and to around 8.0 g/dL at the end of the shock period. In the shock LR group rats, blood hemoglobin further decreased during resuscitation before they died. In rats receiving LR + blood, basal hemoglobin concentration was not restored until 30 min after resuscitation but finally exceeded the basal value. No signs of coagulation or hemolysis were apparent in the blood used for resuscitation, and no hemolysis occurred in rats during or after shock.

Figure 3.

Effect of severe hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation on blood hemoglobin concentration. Rats experienced hemorrhagic shock for 60 min and then were resuscitated either with lactated Ringer solution (LR) or LR + blood, as shown in Figure 1. Values shown represent the mean ± SEM of 4 rats for the sham group and of 6 rats per shock group. The curve of the LR group ends with the death of the first rat of this group. *, P < 0.05 compared with sham group; +, P < 0.05 compared with shock LR + blood group.

Plasma marker enzymes activities and creatinine concentration.

In sham group rats, plasma activities of creatine kinase, LDH, AST, and ALT and creatinine concentration remained fairly low throughout the experiment (Table 2). In the shock LR group rats, these values increased significantly during the shock period (approximately 6-fold for LDH; 4-fold for creatine kinase; 2-fold for AST, ALT, and creatinine). That increase continued during resuscitation, in which another doubling of all parameters occurred, except in creatinine concentration which remained roughly constant during that phase. Until the end of resuscitation, all values of the shock LR + blood group were comparable to those of the shock LR group. In the LR + blood group, the values of all parameters except creatinine concentration increased 6- to 7-fold during the postresuscitation period.

Table 2.

Effects of severe hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation on plasma markers in rats

| Basal | End of shock | End of resuscitation | 2 h after resuscitation | ||

| LDH (U/L) | |||||

| Sham | 78.0 ± 20.2 | 115.6 ± 10.6 | 130.7 ± 16.1a | 124.4 ± 19.0 | |

| Shock LR | 79.0 ± 19.3 | 417.4 ± 89.7ab | 1278.4 ± 241.9ab | ||

| Shock LR + blood | 54.2 ± 4.7 | 454.8 ± 110.1ab | 1153.8 ± 144.8ab | 6541.9 ± 1464.2ab | |

| AST (U/L) | |||||

| Sham | 47.3 ± 3.0 | 59.3 ± 7.6 | 59.5 ± 11.4 | 58.5 ± 11.1 | |

| Shock LR | 50.8 ± 3.3 | 110.8 ± 6.9ab | 188.0 ± 24.4ab | ||

| Shock LR+ blood | 47.8 ± 3.1 | 117.0 ± 17.8ab | 164.2 ± 17.3ab | 735.0 ± 126.3ab | |

| ALT (U/L) | |||||

| Sham | 61.8 ± 4.3 | 85.6 ± 12.4 | 88.5 ± 15.8 | 80.0 ± 13.1 | |

| Shock LR | 64.2 ± 5.6 | 125.9 ± 4.6ab | 246.7 ± 35.3ab | ||

| Shock LR + blood | 56.5 ± 3.1 | 112.8 ± 15.2a | 233.8 ± 23.1ab | 1346.9 ± 127.6ab | |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | |||||

| Sham | 109.3 ± 30.4 | 214.0 ± 36.8a | 188.8 ± 45.0 | 175.7 ± 15.2 | |

| Shock LR | 97.8 ± 29.2 | 415.7 ± 90.2a | 607.8 ± 81.8ab | ||

| Shock LR + blood | 76.3 ± 15.4 | 486.0 ± 142.4ab | 912.5 ± 247.7ab | 5294 ± 770.9ab | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | |||||

| Sham | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | |

| Shock LR | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.90 ± 0.03ab | 0.82 ± 0.02ab | ||

| Shock LR + blood | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 0.94 ± 0.07ab | 1.17 ± 0.09ab | 1.77 ± 0.10ab | |

Animals experienced hemorrhagic shock for 60 min and then were resuscitated either with lactated Ringer solution (LR) or LR + blood, as shown in Figure 1. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Basal values were obtained immediately after insertion of the catheter into the femoral artery.

P < 0.05 compared with basal value of the same group.

P < 0.05 compared with value for sham group at the same time point.

Organ histopathology.

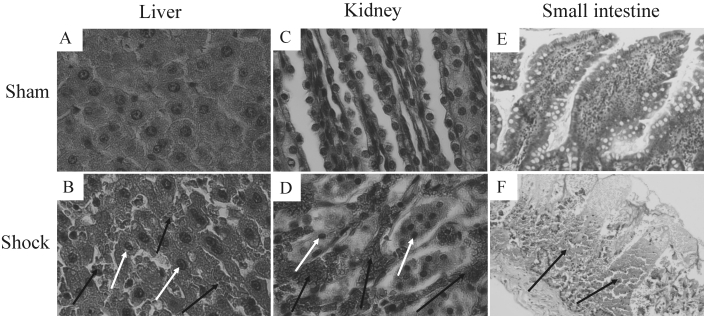

Hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation resulted in pronounced histopathologic changes to liver, kidneys, and small intestine. These changes were most pronounced in the shock LR + blood group (Figure 4), presumably because they formed during the prolonged survival of these rats subsequent to resuscitation. No obvious histologic alterations were observed in samples from lung and heart under these conditions. Organ samples of sham animals showed no injury at all.

Figure 4.

Effects of severe hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation with lactated Ringer solution (LR) + blood on liver, kidney, and small intestine histology. Rats experienced hemorrhagic shock for 60 min and then were resuscitated with LR + blood, as shown in Figure 1. Histologic changes were assessed at the end of the postresuscitation period by using light microscopy. The images shown are representative of samples from 6 shock and 4 sham rats. Note the numerous erythrocytes (black arrows) in liver and kidney tissue and the abnormal nuclear ruffling and chromatin condensation within hepatocytes and kidney cells (white arrows). Pronounced necrotic hemorrhages can be noted in the small intestine. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification: 400× (A through D); 100× (E and F).

Discussion

The methods described and experimental results presented here create a severe but reliable and realistic acute hemorrhagic shock model in rats. During and after a hemorrhagic shock period of 60 min during which MAP was monitored closely and maintained at just 25 to 30 mm Hg (Figure 2), rats exhibited marked organ damage, as demonstrated histologically (Figure 4) and indicated by remarkable release of marker enzyme activity (Table 2). Rats receiving LR + blood for resuscitation reliably survived the entire experimental period, whereas those that were resuscitated with LR alone died shortly thereafter.

To date, several hemorrhagic shock–resuscitation models have been established, but none of them covers all important aspects related to severity, clinical reality, and reproducibility. For example, severe shock with MAP of 30 to 35 mm Hg has been achieved by many groups,35,44,45 but shock periods of 2 h or longer do not reflect human clinical practice. Likewise, a MAP of 25 to 30 mm Hg for only 20 min does not result in life-threatening organ injury and is not clinically relevant,39 whereas 60 min of 45 mm Hg19 does not yield severe hemorrhagic shock.

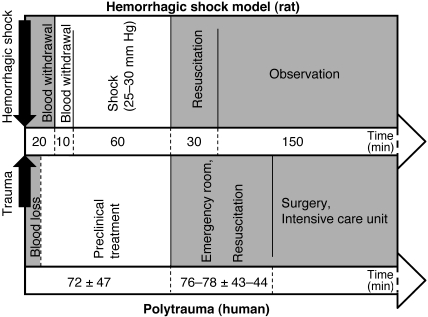

In addition to its high severity, the model we describe here is closely orientated toward human clinical practice. Our experimental schedule of shock induction within 30 min, a hemorrhagic shock period of 60 min, and subsequent resuscitation for 30 min appears to reflect most emergency situations realistically20 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of timelines of the hemorrhagic shock model presented (upper bar) and the current practice for treatment after severe trauma and blood loss in humans according to the Trauma Register of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie (lower bar).20

The administration of anesthetics and analgesics can decisively influence the effects of hemorrhage and trauma.3,25,26 Humans in hemorrhagic shock subsequent to traumatic events often receive isoflurane or ketamine–xylazine.21 Ketamine seems to be an ideal emergency analgesic, in that it positively influences blood pressure, whereas isoflurane, unlike ketamine, improves microcirculation. In line with this practice, the rats in our model received isoflurane and ketamine. In preliminary studies, xylazine itself led to a drop in MAP in sham animals and thus was not used. In addition, although often provided to human shock patients, we did not use opiates, because they can decrease peristalsis and thus may influence injury of the gut; in addition, some opiates decrease tissue injury due to ischemia–reperfusion.42 With the use of ketamine and lidocaine, we were able to decrease the isoflurane concentration needed (especially during placement of incisions and catheters) and thus its hypotensive effects. Lidocaine was used, in addition to ketamine, for local analgesia because of its rapid onset of action.

In the present experiments, rats (male Wistar, 400 to 450 g) reliably survived a hemorrhagic shock-induced decrease in MAP to 25 to 30 mm Hg for at least 60 min. Under the same experimental settings, a MAP of 20 mm Hg or lower resulted in death of the rats in 20 min and a MAP of 21 to 24 mm Hg led to highly variable survival times in preliminary studies. MAP adjustment to pressures as low as 25 to 30 mm Hg have the additional advantage that the rats’ blood pressure usually does not increase again once the MAP has been adjusted. At higher MAP (for example, 35 to 45 mm Hg), regulatory mechanisms are still effective, making repeated intervention (further withdrawal of blood) necessary, which will negatively affect reproducibility. Consequently, the most severe hemorrhagic shock model that maximally affects MAP in rats and yet is highly reproducible should neither be based on a MAP below 25 mm Hg (because the effects are no longer reproducible) nor on much higher MAP values, because the effects are no longer severe. Infusion of 0.9% NaCl at 5 mL/kg/h, administered to compensate for evaporation through the respiratory epithelium and surgery wounds, was necessary to ensure stabilization of the MAP throughout the shock period. Pharmacologic agents and potentially protective substances can be added to this infusion to study their effects during and after hemorrhagic shock. Hemorrhagic shock between 25 to 30 mm Hg for 60 min allowed a reasonably prolonged postresuscitation period—and therefore opportunity to study resuscitation regimens—and approximates the most physiologically demanding condition.

Due to the severity of the shock phase, marked tissue injury became apparent shortly after resuscitation (Table 2; Figure 4). The tissue injuries and short survival time in the LR group were not due to decreased blood hemoglobin concentration (Figure 3), which was sufficient to ensure tissue oxygenation41 especially at 100% inspiratory oxygen, but to hypovolemia and altered or interrupted tissue perfusion. During both the hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation phases, massive fluid shifts occurred in both directions between the interstitial space and vessels, as indicated by the changes in hemoglobin concentration (Figure 3).

The composition of the fluids used for resuscitation (LR compared with LR + blood) decisively affected rat survival times. Survival times were prolonged significantly by resuscitation with blood compared with pure LR, consistent with other studies22 and clinical experience.31 The model therefore allows 100% survival of subjects, which is a particular advantage for studies requiring organ histopathology and endpoint blood analyses. Alternatively, survival time can be assessed as an important and meaningful parameter for evaluation of protective approaches or various resuscitation protocols.

In many models, heparin-based anticoagulants are administered to the animals prior to shock induction or are added to the collected blood to prevent its coagulation until its use for resuscitation.24,25,39 However, under comparable human clinical situations, heparins are not used and may even be contraindicated.11 Moreover, heparins have been reported to mediate protective effects during hemorrhagic shock,5,32,43 and this result is unfavorable when, for example, the effects of drugs are intended to be studied. A more appropriate anticoagulant in this setting is ACDA, a citrate-based solution, because it is already contained in human stored blood that is used for resuscitation, and because it provides no protection against hemorrhagic shock.19 Therefore, we used ACDA instead of heparin in the current study.

Activation of coagulation and mild hemolysis are risks associated with blood sampling through catheters and during storage of collected blood; these side effects cannot be excluded completely. Infusion of hemolyzed blood could lead, for example, to artificially high plasma LDH activities and oxidative stress and kidney injury due to free hemoglobin. The intravenous application of invisible clots can lead to microembolism, in vivo activation of the coagulation cascade, and sudden unexpected death of the animals.34 To verify that the blood used for resuscitation was not hemolytic or coagulated, the plasma hemoglobin concentration and LDH activity in the collected blood were quantified before and after resuscitation, and blood filters used to avoid infusion of microclots; none of our rats demonstrated any indication of abnormal coagulation or hemolysis.

In our model, ACDA-treated blood was mixed with LR (1:2) prior to infusion. The mixture or coinfusion of LR and blood introduces a risk that the calcium in LR exceeds the Ca2+-chelating capability of anticoagulants like ACDA. This situation could result in clot formation, especially at ambient temperature.10,36 We minimized this risk by prewarming the blood–LR and by immediately infusing the mixture at 37 °C. However, care must be taken to exclude coagulation (for example, through examination of blood smears). Alternatively, LR and the collected blood can be administered through separate catheters. Normal saline must not be used for resuscitation, because it can lead to hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis at high rates of infusion.15,40

In conclusion, the hemorrhagic shock model described here represents a severe but reproducible and realistic model in rats. The model allows reliable assessment of parameters such as survival times, plasma marker enzyme activity, and histopathologic alterations. Despite the limitations of animal studies in mimicking clinical reality, the timeline of our shock model reflects the current practice of treatment after severe trauma and blood loss in humans. Moreover, our methodic approach minimizes artificial and misleading influences like heparinization and the risk of unnoticed hemolysis and coagulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Dr F Köhler Chemie (Bensheim, Germany) and by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. Ke 1359/2-1).

References

- 1.Anaya-Prado R, Toledo-Pereyra LH, Collins JT, Smejkal R, McClaren J, Crouch LD, Ward PA. 1998. Dual blockade of P-selectin and β2-integrin in the liver inflammatory response after uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock. J Am Coll Surg 187:22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badin J, Boulain T, Ehrmann S, Skarzynski M, Bretagnol A, Buret J, Benzekri-Lefevre D, Mercier E, Runge I, Garot D, Mathonnet A, Dequin PF, Perrotin D. 2011. Relation between mean arterial pressure and renal function in the early phase of shock: a prospective, explorative cohort study. Crit Care 15:R135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahrami S, Benisch C, Zifko C, Jafarmadar M, Schöchl H, Redl H. 2011. Xylazine–diazepam–ketamine and isoflurane differentially affect hemodynamics and organ injury under hemorrhagic–traumatic shock and resuscitation in rats. Shock 35:573–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrantes F, Tian J, Vazquez R, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. 2008. Acute kidney injury criteria predict outcomes of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 36:1397–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Call DR, Remick DG. 1998. Low-molecular-weight heparin is associated with greater cytokine production in a stimulated whole-blood model. Shock 10:192–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JE, Garrison RN, Zakaria ER. 2006. Clinical peritoneal dialysis solutions modulate white blood cell–intestinal vascular endothelium interaction. Am J Surg 192:610–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capone AC, Safar P, Stezoski W, Tisherman S, Peitzman AB. 1995. Improved outcome with fluid restriction in treatment of uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock. J Am Coll Surg 180:49–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang TM, Varma R. 1992. Effect of a single replacement of one of Ringer lactate, hypertonic saline/dextran, 7g% albumin, stroma-free hemoglobin, o-raffinose polyhemoglobin, or whole blood on the long-term survival of unanesthetized rats with lethal hemorrhagic shock after 67% acute blood loss. Biomater Artif Cells Immobilization Biotechnol 20:503–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Mendonça A, Vincent JL, Suter PM, Moreno R, Dearden NM, Antonelli M, Takala J, Sprung C, Cantraine F. 2000. Acute renal failure in the ICU: risk factors and outcome evaluated by the SOFA score. Intensive Care Med 26:915–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickson DN, Gregory MA. 1980. Compatibility of blood with solutions containing calcium. S Afr Med J 57:785–787 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernits M, Mohan PS, Fares LG, 2nd, Hardy H., 3rd 2005. A retroperitoneal bleed induced by enoxaparin therapy. Am Surg 71:430–433 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eser O, Kalkan E, Cosar M, Buyukbas S, Avunduk MC, Aslan A, Kocabas V. 2007. The effect of aprotinin on brain ischemic–reperfusion injury after hemorrhagic shock in rats: an experimental study. J Trauma 63:373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Commission [Internet] 2010. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. [Cited August 2011]. Available at: http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2010: 276:0033:0079:eN:PDF

- 14.Fan J. 2010. TLR crosstalk mechanism of hemorrhagic shock-primed pulmonary neutrophil infiltration. Open Crit Care Med J 2:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gheorghe C, Dadu R, Blot C, Barrantes F, Vazquez R, Berianu F, Feng Y, Feintzig I, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. 2010. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis following resuscitation of shock. Chest 138:1521–1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greiffenstein P, Mathis KW, Stouwe CV, Molina PE. 2007. Alcohol binge before trauma–hemorrhage impairs integrity of host defense mechanisms during recovery. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31:704–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halvorsen L, Gunther RA, Dubick MA, Holcroft JW. 1991. Dose–response characteristics of hypertonic saline–dextran solutions. J Trauma 31:785–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hierholzer C, Billiar TR. 2001. Molecular mechanisms in the early phase of hemorrhagic shock. Langenbecks Arch Surg 386:302–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoppen RA, Corso CO, Grezzana TJ, Severino A, Dal-Pizzol F, Ritter C. 2005. Hypertonic saline and hemorrhagic shock: hepatocellular function and integrity after 6 h of treatment. Acta Cir Bras 20:414–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hußmann B, Taeger G, Lefering R, Waydhas C, Nast-Kolb D, Ruchholtz S, Lendemans S; Trauma Register der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie 2011. [Lethality and outcome in multiple injured patients after severe abdominal and pelvic trauma: Influence of preclinical volume replacement - an analysis of 604 patients from the trauma registry of the DGU.] Unfallchirurg 114:705–712 [Article in German] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katastrophenmedizin. Leitfaden für die ärztliche Versorgung im Katastrophenfall, vol 5 2010. Munich (Germany): Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knotzer H, Pajk W, Maier S, Dünser MW, Ulmer H, Schwarz B, Salak N, Hasibeder WR. 2006. Comparison of lactated Ringer, gelatin, and blood resuscitation on intestinal oxygen supply and mucosal tissue oxygen tension in haemorrhagic shock. Br J Anaesth 97:509–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C, Xu DZ, Feketeova E, Nemeth Z, Kannan KB, Haskó G, Deitch EA, Hauser CJ. 2008. Calcium entry inhibition during resuscitation from shock attenuates inflammatory lung injury. Shock 30:29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legrand M, Mik EG, Balestra GM, Lutter R, Pirracchio R, Payen D, Ince C. 2010. Fluid resuscitation does not improve renal oxygenation during hemorrhagic shock in rats. Anesthesiology 112:119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lomas-Niera JL, Perl M, Chung CS, Ayala A. 2005. Shock and hemorrhage: an overview of animal models. Shock 24:33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majde JA. 2003. Animal models for hemorrhage and resuscitation research. J Trauma 54:S100–S105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathis KW, Sulzer J, Molina PE. 2010. Systemic administration of a centrally acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor improves outcome from hemorrhagic shock during acute alcohol intoxication. Shock 34:162–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molina MF, Whitaker A, Molina PE, McDonough KH. 2009. Alcohol does not modulate the augmented acetylcholine-induced vasodilatory response in hemorrhaged rodents. Shock 32:601–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molina PE, Zambell KL, Norenberg K, Eason J, Phelan H, Zhang P, Vande Stouwe C, Carnal JW, Porreta C. 2004. Consequences of alcohol-induced early dysregulation of responses to trauma–hemorrhage. Alcohol 33:217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moochhala S, Wu J, Lu J. 2009. Hemorrhagic shock: an overview of animal models. Front Biosci 14:4631–4639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore EE, Moore FA, Fabian TC, Bernard AC, Fulda GJ, Hoyt DB, Duane TM, Weireter LJ, Jr, Gomez GA, Cipolle MD, Rodman GH, Jr, Malangoni MA, Hides GA, Omert LA, Gould SA. 2009. Human polymerized hemoglobin for the treatment of hemorrhagic shock when blood is unavailable: the USA multicenter trial. J Am Coll Surg 208:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rana MW, Singh G, Wang P, Ayala A, Zhou M, Chaudry IH. 1992. Protective effects of preheparinization on the microvasculature during and after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma 32:420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossaint R, Cerny V, Coats TJ, Duranteau J, Fernández-Mondéjar E, Gordini G, Stahel PF, Hunt BJ, Neugebauer E, Spahn DR. 2006. Key issues in advanced bleeding care in trauma. Shock 26:322–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosskopf K, Wagner T, Schallmoser K, Eibl M, Apfelbeck U, Lanzer G. 2001. ACDA is effective in preventing clots in cryopreserved autologous peripheral blood stem cell concentrates (PBSC) at the time of thawing. Infus Ther Transfus Med 28:57 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell DH, Barreto JC, Klemm K, Miller TA. 1995. Hemorrhagic shock increases gut macromolecular permeability in the rat. Shock 4:50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryden SE, Oberman HA. 1975. Compatibility of common intravenous solutions with CPD blood. Transfusion 15:250–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato H, Tanaka T, Kita T, Tanaka N. 2010. A quantitative study of lung dysfunction following haemorrhagic shock in rats. Int J Exp Pathol 91:267–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sihler KC, Napolitano LM. 2010. Complications of massive transfusion. Chest 137:209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein HJ, Hinder RA, Oosthuizen MMJ. 1990. Gastric mucosal injury caused by hemorrhagic shock and reperfusion: Protective role of the antioxidant glutathione. Surgery 108:467–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steurer MA, Berger TM. 2011. [Infusion therapy for neonates, infants, and children]. Anaesthesist 60:10–22 [Article in German] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szaflarski NL. 1996. Physiologic effects of normovolemic anemia: implications for clinical monitoring. AACN Clin Issues 7:198–211, quiz 326–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tubbs RJ, Porcaro WA, Lee WJ, Blehar DJ, Carraway RE, Przyklenk K, Dickson EW. 2002. Delta opiates increase ischemic tolerance in isolated rabbit jejunum. Acad Emerg Med 9:555–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang P, Singh G, Rana MW, Ba ZF, Chaudry IH. 1990. Preheparinization improves organ function after hemorrhage and resuscitation. Am J Physiol 259:R645–R650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang R, Harada T, Mollen KP, Prince JM, Levy RM, Englert JA, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Yang L, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Harbrecht BG, Billiar TR, Fink MP. 2006. AntiHMGB1 neutralizing antibody ameliorates gut barrier dysfunction and improves survival after hemorrhagic shock. Mol Med 12:105–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhong Z, Enomoto N, Connor HD, Moss N, Mason RP, Thurman RG. 1999. Glycine improves survival after hemorrhagic shock in the rat. Shock 12:54–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zingarelli B, Chima R, O'Connor M, Piraino G, Denenberg A, Hake PW. 2010. Liver apoptosis is age dependent and is reduced by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298:G133–G141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]