Abstract

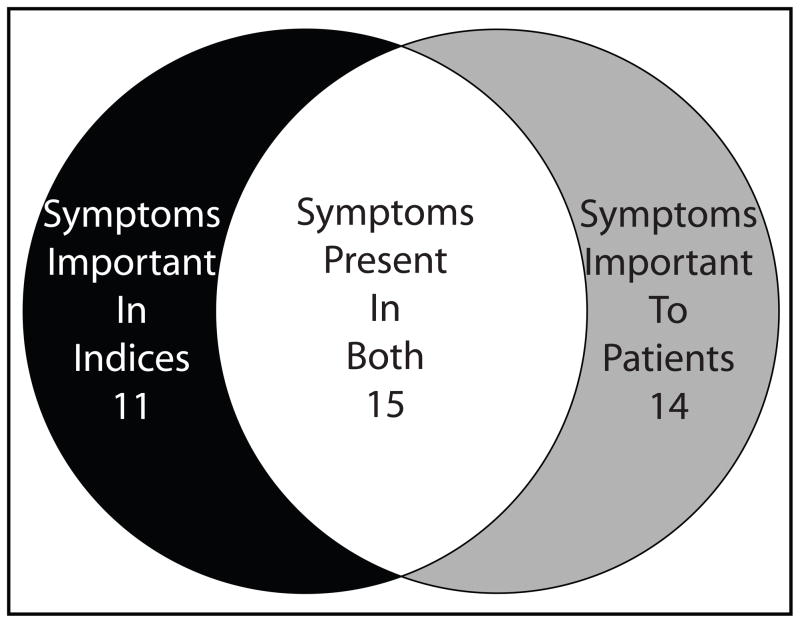

It has been assumed that the symptoms measured in disease activity indices for ulcerative colitis reflect those symptoms that patients find useful in evaluating the severity of a disease flare. In this qualitative focus group study, we aimed to identify which symptoms are important to patients and to compare these symptoms with a comprehensive list of commonly measured symptoms to determine/evaluate whether the patient-reported important symptoms are represented in current disease activity indices for ulcerative colitis. Patients in this sample confirmed 15 symptoms but not 11 other symptoms found in common ulcerative colitis activity indices. Patients identified an additional 14 symptoms not included in commonly used ulcerative colitis activity indices, which they believed to be important in evaluating the onset or severity of an ulcerative colitis flare. Current indices capture only a portion of the clinical symptoms that are important to patients in an ulcerative colitis flare, and may neither accurately measure nor fully reflect patients’ experience of ulcerative colitis. These findings present an opportunity to develop better patient-centered measures of ulcerative colitis.

Keywords: focus groups, inflammatory bowel disease, patient-reported outcomes, qualitative research, symptom domains, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis adversely affects many patients and current treatments are relatively ineffective

Ulcerative colitis adversely affects the quality of life of many patients with symptoms that include frequent diarrhea, urgent bowel movements, rectal bleeding, and fatigue. Patients’ quality of life and economic productivity are significantly impaired by chronic ulcerative colitis [1–3]. This disease often strikes individuals in their teens and twenties, and continues to wax and wane for the remainder of their lives. The severity of the symptoms, as well as the unpredictability of flares of disease, can significantly impair the lives of those affected [4].

Current therapies for ulcerative colitis are only modestly effective, as up to 45% of patients eventually have total surgical removal of their colon [5]. This is a daunting and irreversible choice for young patients to make. It is particularly difficult for young females, in whom the scarring of the pelvic organs after total colectomy can result in a three-fold increase in infertility [6]. Therefore, it is quite important to evaluate all the symptoms that patients perceive as important in assessing disease activity, to determine whether the current medical treatment is truly effective.

Many disease activity indices exist for ulcerative colitis, but none have been developed with formal patient input

There is no consensus gold standard for the evaluation of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. This is illustrated in numerous recent clinical trials, in which investigators measured several different indices of disease activity, as no one index is considered sufficient. There are many indices for the measurement of ulcerative colitis disease activity, including Truelove and Witt’s classification of mild, moderate, and severe disease; the St Mark’s Index, which empirically added endoscopy in 1978; simplified versions of the St Mark’s Index, including the Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index and the Mayo Score; and noninvasive versions, including the Seo Index and the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index [7–12].

The diversity of indices suggests that none of these has proven satisfactory, and none was developed with patient input. In addition, it has never been established that any of these indices actually measures all of the important symptoms of ulcerative colitis.

Ulcerative colitis lacks a validated measurement instrument such as the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index in Crohn’s disease [13]. Furthermore, the indices that do exist for ulcerative colitis were not constructed in a patient-centered manner to attempt to capture the symptoms experienced by patients. Therefore, our study group aimed to investigate through focus groups that what symptoms does patients with ulcerative colitis experience during their disease process.

We also aimed to identify through the focus group discussions that additional symptoms and themes that may be important to patients that are not currently captured in existing indices, so an open-ended format was used. Other factors including quality of life, anxiety, and stress were secondary issues we attempted to capture using the life world approach developed by Barry that allows for better care for patients [14].

This qualitative study approach using focus groups and interviews have been used before in ulcerative colitis patients. In Welfare’s [15] focus group study of ulcerative colitis patients, published in this journal in 2006, he used qualitative methods to find that patients with ulcerative colitis are able to identify many different areas of research that are important to them.

Our study findings would represent the initial step in the development of a formally validated and patient-centered ulcerative colitis disease activity index that would have the same clinical and research applications as the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index does in the study and treatment of Crohn’s disease.

Methods

Approach

We used qualitative methods to learn how patients with ulcerative colitis experience the symptoms of their disease and how these patients perceive their symptoms as a measure of the level of activity of their ulcerative colitis. We were specifically interested in exploring whether the symptom domains patients considered important in the assessment of their disease activity corresponded with the symptom domains found in current disease activity indices for ulcerative colitis. We defined symptoms for the purposes of this manuscript broadly as any symptom or sign that could be used by the patient to assess their disease activity level. Symptom domains discussed by patients in the focus groups were then compared with those from current disease activity indices.

Sampling

We offered participation in one of our focus group sessions to all patients with ulcerative colitis who had been seen in the gastroenterology clinic at the University of Michigan. Eligible patients were identified by ICD-9 code 556 (ulcerative colitis) in the University of Michigan medical records. Patients were offered the opportunity to participate through a direct mailing. Interested individuals contacted our study team and were screened by phone for eligibility. Patients who were interested in participating were given information on when and where the focus groups would meet and how they would be conducted. A total of 31 patients contacted us, all but nine of whom were able to participate.

Inclusion criteria included age above 18 years, diagnosis of ulcerative colitis confirmed by biopsy, and willingness to participate in and travel to the focus group site. Exclusion criteria included history of colectomy. We enrolled a total of 22 participants who participated in one of five separate semistructured focus groups led by a moderator (P.A.W.). Demographic and disease characteristics of participants are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive data on participants

| Characteristics | Participants (n=22) |

|---|---|

| Women/men | 12/10 |

| Percent Caucasian | 95.5% |

| Median (range) (IQR), age in years | 54.34 (23.82–74.06), IQR (48.47–64.27) |

| Median (IQR), disease duration in years | 13.50 (9.73–23.50) |

| Disease location | |

| Proctitis | 2 of 22 |

| Left-sided | 8 of 22 |

| Pancolitis | 12 of 22 |

| Medications | |

| Prior steroids | 16 of 22 |

| Current steroids | 3 of 22 |

| Current 5-ASAs | 19 of 22 |

| Current immunomodulators | 4 of 22 |

| Current infliximab | 1 of 22 |

IQR, interquartile range.

The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. We obtained written informed consent from all study participants.

Data collection

We conducted in-depth focus groups with the enrolled participants on the subject of their experience of symptoms of ulcerative colitis until redundancy in responses was recognized. An additional two focus groups were conducted to achieve more complete collection of symptoms. Each focus group session lasted between 1 and 2λh. All five focus group sessions took place during April and May 2006.

One of us (P.A.W.) served as the moderator for the focus groups. The moderator used a question guide consisting of nine questions meant to stimulate discussion between participants on the subject of their ulcerative colitis symptoms and disease experience as seen in Table 2. The moderator explained to each focus group a set of basic rules to encourage participant participation and reassured participants that there are no right or wrong answers to these questions. Beyond these basic rules, the participants were free to discuss whatever they saw as relevant to the symptoms experienced personally in their disease. The moderator’s task was to listen and observe and only ask additional questions to make sure everyone stayed on topic. Our goal was to make participants speak freely and interact with each other in discussing their experience of ulcerative colitis.

Table 2.

Question guide for moderator of focus groups

|

Analysis of focus group data

Each focus group meeting was audiotaped and fully transcribed. Each transcript was entered into NVivo version 2.0. Two members of the study team (J.C.J. and A.K.W) independently reviewed each transcript with a holistic view of symptoms and themes from each of the five focus group meetings and generated a list of symptom domains and common themes discussed by participants of each focus group [16]. These lists were compared for agreement and consensus was reached [17]. This list served as a template for a coding scheme used to analyze each transcript. The transcripts were independently coded by symptom domain and theme by J.C.J. and A.K.W. and codes were compared for agreement.

Pooling of symptoms from common indices

We gathered symptom domains assessed in several commonly used ulcerative colitis disease activity indices (Mayo Index, Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index, St Mark’s Index, Lichtiger Index, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index, and Seo Index) [8–10,12,18–20]. These were listed and pooled, and redundant symptom domains were removed. This produced a list of 26 unique symptom domains from the common disease activity indices in ulcerative colitis.

Comparison of symptoms reported in focus groups to symptoms from pooled disease activity indices

The lists were directly compared to determine (i) which symptoms were present in both the focus group list and in the common indices list; (ii) which symptoms were only present in the indices; and (iii) which symptoms were reported by patients to be important, but were not measured by any of the common disease activity indices.

Results

In the setting of semistructured focus groups with other individuals who also had ulcerative colitis, participants confirmed some symptom domains from commonly accepted ulcerative colitis disease activity indices while failing to mention or discuss others. In addition, participants identified additional symptom domains and themes relevant to their disease activity that are not currently evaluated in ulcerative disease activity indices. A total of 29 symptom domains and themes were reported.

Several of the symptom domains found in current disease activity indices were discussed frequently and in depth in each focus group (including stool blood, cramps, endoscopic correlation, stool consistency, and stool frequency), whereas several were mentioned only once or twice (anorexia and abdominal tenderness). Others were discussed often and in-depth but are not currently assessed in ulcerative colitis disease activity indices (stool mucus, constipation, flatulence, and others). Focus group participants also spent significant time in discussing the importance of anxiety concerning their disease symptoms and its influence on quality of life, as well as possible ‘triggers’ that led to a flare or increase in disease activity.

Comparison to the comprehensive list of symptoms from commonly used ulcerative colitis disease activity indices

By comparing these two lists (focus group list of symptom domains vs. the pooled list from current indices), we were able to identify symptoms common to both lists (15 total), unique to the list generated from the focus group transcripts (14 total), or found in the commonly used ulcerative colitis disease activity indices but not mentioned by any participants of the focus groups (total 11). (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ulcerative colitis disease symptoms in current indices and reported by patient focus groups

| Index symptoms not reported by patients (n=11) | Index symptoms endorsed by patients (n=15) | Novel symptoms reported by patients that are not in the current indices (n=14) |

|---|---|---|

| Tachycardia | Fever | Flatulence (quantity) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | Anemia | Flatulence (odor) |

| Albumin | Abdominal tenderness | Stool mucus |

| Investigator’s global assessment (well-being) | Endoscopic correlation | Fatigue |

| Patient’s functional assessment | Anorexia | Cold sweats (chills, shakes) |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Blood in stool/rectal bleeding | Lightheadedness |

| Erythema nodosum | Abdominal pain | Aching |

| Uveitis | Stool consistency | Bloating/distention |

| Iritis | Nausea/vomiting | Anxiety (distance to bathroom, etc.) |

| Need for antidiarrheals | Cramps | Borborygmi |

| Arthritis | Daytime bowel movements | Constipation |

| Nighttime bowel movements | Skin in bowel movements | |

| Urgency | Weight loss | |

| Frequency Incontinence | Insomnia |

The most salient symptoms discussed in the focus groups that were also present in current disease activity indices included the symptoms illustrated below with representative quotes from participants.

Cramping

This is a common symptom for patients that correlated with worsening disease activity.

I would have bouts of cramping so bad that I would roll up on the floor into [a] ball…and I didn’t know if I was going to, if anything was going to come out of me until that passed, and suddenly I would have a bowel movement. Now those were very painful.

Stool frequency

The frequency of bowel movements is one of the most common ways patients assess their disease activity and severity. There is a wide variation between participants and within participants over time with the waxing and waning of the disease.

Iaverage maybe two or three bowel movements on a normal day, and um, I had a flareup this fall, and it just came on…so I was just in the bathroom basically all day, and then I had to go to the hospital, it wasn’t just like once every half hour, it was like every five minutes.

Stool blood

The presence of stool blood created anxiety and was a good correlate for disease activity for many participants.

Sometimes, if I have solids, you can see red streaks in it, and then it’s a warning sign to say, ‘uh oh, there’s trouble ahead.

…I had significant passing of blood which they say, in all honesty, was it a lot at one time? No, but no matter how much they tell you not to worry, when blood is leaking [from] your body in a manner it should not be, you worry.

Stool consistency

There was extensive discussion about changes in stool consistency. Each person seemed to have a range of consistencies that indicate different things to them about the health of their colon…

A bowel movement equals anything that’s not urinating.

It’s either solid or liquid, A or B, 1 or 2.

For me personally, I don’t worry if it’s anything on the solid side of, I don’t know, you know, like Cream of Wheat or mashed potatoes, then that’s good, then I don’t care about that. But if it’s anything on the liquid side, or especially if there’s a high gas content, then I worry…

Bowel movements to us, is probably equal to like, ‘snow’ is to Eskimos.

They’ve got like ten different words for it depending on the consistency, and maybe what we need are ten different words.

Correlation between disease activity and endoscopic findings

There was a consensus that endoscopic findings would usually affirm patients’ own assessment of their level of disease activity.

Testing [endoscopy] has always been pretty much a confirmation of how I’m feeling at the time.

The colonoscopy reports and photos are basically, ‘well, here’s what this looks like and this looks like and here’s the issue.’ So, they’re pretty in synch.

Importance of novel symptom domains not previously included in ulcerative colitis disease activity indices

Several salient symptoms were discussed in focus groups that are important to many patients but are not currently captured in available indices. These are illustrated below with representative quotes from participants.

Stool mucus

This seems to be a common and prominent warning sign of impending worsening of symptoms.

If I have mucus, it’s usually first, but I do look every time I go. You have to look every time you go just to make sure, but for the most part, I’m pretty consistent until I have a flareup and then it’s pretty bad too.

Um, and the active part of it was when you’d see some mucus on the stool.

That’s how mine starts. For me, when I start with the mucus, I know I’m in trouble.

Mucus happens right before everything falls apart.

The ability to differentiate gas from liquid or solid in the rectum when urgency occurs

Participants can be greatly affected by a loss of the ability to differentiate rectal urgency due to gas from rectal urgency due to stool, mucus, or blood. They usually lose this ability during a flare, and need to go to the toilet anytime they have urgency, to avoid the risk of incontinence.

If I do have gas, I don’t dare let it pass because all sorts of other stuff could come with it.

When I’m having a flare, I can’t tell if it’s gas or not. Gas can carry some other stuff with it. When there’s a flareup, I think gas counts because there’s no such thing as just gas.

Rapid bowel movements after eating

The concern among participants that eating anything results in the need to have a bowel movement has also been supported during a flare.

I don’t eat breakfast because I know within so many minutes of eating that I will need to go the bathroom.

When I’ve got a flareup going, I mean, it’s always, I eat, and then half an hour later I’m in the bathroom.

Other factors in the experience of ulcerative colitis disease activity

Several areas beyond specific symptoms were discussed as part of the experience of having ulcerative colitis, focused largely on anxiety, the possibility that specific foods might trigger flares, the unpredictability of flares, and the lack of self-control and bowel control.

Anxiety and control over activities

Participants acknowledged a large amount of anxiety resulting from a pattern of their symptoms controlling their lives and the resulting effects of their disease on their quality of life.

I’ve got a full-blown flareup, and uh, I try and schedule things around when I’ve got to go to the bathroom in a half hour, so let’s not start this meeting or let’s get this meeting over, um, ‘excuse me, I’ve gotta go.

…if I don’t go in the morning, then it’s in the back of my head, ‘Ok, when’s it going to hit?’ But if I go in the morning, right after I get up, I have no worries the rest of the day.

You end up planning your whole life around what your gut is doing.

I mean, you plan your life around it [concern for going to bathroom].”

When it started, I just had to stay home because so often I couldn’t handle it and it had absolutely no control, and when you teach, you cannot have that in the classroom.

Food as trigger of flare

Participants frequently discussed the possibility that certain foods could trigger flares, but had great difficulty in identifying common themes across participants.

I never could figure out what triggers it. When I’ve got a flareup going, I mean, it’s always, I eat, and then half an hour later I’m in the bathroom.

I know until I kept a food journal, I had no concept of what would or wouldn’t trigger it. I just – it’s hard to isolate.

Discussion

The symptoms traditionally measured in the assessment of disease activity in ulcerative colitis are based on the earlier work of developers of activity indices. These symptoms were, however, largely identified by physician researchers, rather than patients, and may not represent the symptoms important to patients. We found that qualitative research has been used before identifying topics for research that are important to people with ulcerative colitis and this methodology was used in our study to identify a number of symptoms that are important to patients that are not currently measured in the assessment of ulcerative colitis disease activity [15]. This represents an opportunity to improve our measurement of ulcerative colitis by developing ways to measure all of the important symptom domains.

These results may also help physicians elicit the symptoms during history-taking that are important to patients with ulcerative colitis. Our study identified 14 symptoms that are not represented in current indices. Fifteen of the symptoms included on current indices were endorsed by patients as important, but 11 currently measured symptoms do not resonate with patients’ experiences (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Results of the comparison between the symptoms from the pooled disease activity indices and those reported by focus groups.

This study has several limitations. First, the study population was relatively homogenous and cultural and language biases may limit symptom reporting. However, there is a common biology of ulcerative colitis across cultures, and the focus groups were conducted to redundancy and two groups, so we would expect to elicit all of the important symptoms. Second, as this is a qualitative study, we collected many symptoms but could not measure the relative importance of the symptoms. Future work should focus on evaluating these symptoms quantitatively, focusing on whether these symptoms are reproducible and responsive to change.

Notably, we did not have any reporting by patients of concerns about extraintestinal manifestations of disease, including pyoderma gangrenosum or uveitis. It is possible that this small sample of patients simply had no experience with extraintestinal manifestations, or that they were not reported because they were considered embarrassing. This seems somewhat less likely because these patients were sharing their bowel habits in great detail, but it is possible. We are planning future studies with individual, confidential surveys to address this issue. An alternative interpretation of several of the symptoms reported by patients is that these could be attributed to irritable bowl syndrome (IBS) and/or postinflammatory IBS. Postinflammatory IBS has been reported to be relatively common (33–42% prevalence) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [21]. Contrary to this view, a recent report suggests that IBS-related symptoms in IBD actually correlate with increased fecal calprotectin levels, suggesting that these symptoms may actually be due to occult inflammation. In either case, these symptoms that are important to patients must be treated to achieve therapeutic success and restore ulcerative colitis patients to health [22].

Two unexpected findings of this study were the importance to patients of the anxiety induced by the unpredictable course of the disease, and the frequent focus of patients on attempting to eliminate particular foods as a possible source of exacerbations. This goes along with current data that suggest that certain bacteria are associated with IBD but it is unclear how this relates to foods [23]. These findings suggest that patients would benefit greatly from a prognostic marker that had a high negative predictive value for future flare. Patients would also benefit if physicians can spend more time with patients discussing (and perhaps further researching) the peer-reviewed data on the role of food in ulcerative colitis, as patients receive a variety of conflicting messages from commercial sources on this topic, frequently through the internet.

We also found that participants’ experience of endoscopy was that the findings largely confirmed their own impression of their disease activity, suggesting that this invasive test added little to their evaluation, which is concordant with the findings of a previous study by our group [24].

This qualitative research study represents a first step in the patient-centered development of improved measures of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. The symptoms that we currently measure in disease activity indices are not always important to patients, and there are a number of symptoms important to patients that we do not measure at all. This represents an opportunity to improve our measurement of ulcerative colitis. Our group is currently developing survey questions and response scales to measure all of these symptom domains in patients with ulcerative colitis. These findings also suggest that a broader assessment of symptoms in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical settings may be valuable in gaining a better understanding of the patient’s disease experience.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for their participation. They also thank Jane Forman, ScD, MHS, for guidance in using qualitative methods effectively in their study design and execution of this study, and Sherry Hudson for transcribing all of the audiotaped focus group sessions. They thank Alissa Dandalides and Ashley Rich, research assistants who helped with the focus groups. This article was presented as an oral presentation at Digestive Disease Week in Washington, D.C., May 2007. This study was funded by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. J.C.J. was supported by the General Clinical Research Center (NIH Grant M01-RR-00042) at the University of Michigan. The funding source peer-reviewed the original proposal and receives annual updates. The funding sources were not involved in study design, data collection or analysis, data interpretation, or writing. The authors work was entirely independent on the funders. No professional writers were involved in the writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

Contributors: P.D.R.H. had the original idea for the project, was the principal investigator, and is guarantor. P.D.R.H. and P.A.W. contributed to the conception and design of the project. T.K. contacted and conducted all screening interviews of potential participants and arranged their participation. P.A.W. conducted the focus group sessions. A.K.W. and J.C.J. read and coded transcripts. J.C.J. entered data into the qualitative research software program. A.K.W. and J.C.J. developed and revised the symptom domain categories and themes; P.D.R.H. critically reviewed these findings for completeness. A.K.W. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from J.C.J. and P.D.R.H. P.A.W. and P.D.R.H. critically reviewed the study and suggested revisions. All authors approved the final version of the article.

References

- 1.Loftus EV., Jr Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irvine EJ. Review article: patients’ fears and unmet needs in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 (Suppl 4):54–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longobardi T, Jacobs P, Bernstein CN. Work losses related to inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1064–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casellas F, Lopez-Vivancos J, Casado A, Malagelada JR. Factors affecting health related quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:775–781. doi: 10.1023/a:1020841601110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leijonmarck CE, Persson PG, Hellers G. Factors affecting colectomy rate in ulcerative colitis: an epidemiologic study. Gut. 1990;31:329–333. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.3.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waljee A, Waljee J, Morris AM, Higgins PD. Threefold increased risk of infertility: a meta-analysis of infertility after ileal pouch anal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2006;55:1575–1580. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.090316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041–1048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4947.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell-Tuck J, Bown RL, Lennard-Jones JE. A comparison of oral prednisolone given as single or multiple daily doses for active proctocolitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13:833–837. doi: 10.3109/00365527809182199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherland LR, Martin F, Greer S, Robinson M, Greenberger N, Saibil F, et al. 5-Aminosalicylic acid enema in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis, proctosigmoiditis, and proctitis. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1894–1898. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo M, Okada M, Yao T, Ueki M, Arima S, Okumura M. An index of disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:971–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F., Jr Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barry CA, Stevenson FA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley CP. Giving voice to the lifeworld. More humane, more effective medical care? A qualitative study of doctor-patient communication in general practice. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:487–505. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welfare MR, Colligan J, Molyneux S, Pearson P, Barton JR. The identification of topics for research that are important to people with ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:939–944. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000230088.91415.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strandberg EL, Ovhed I, Borgquist L, Wilhelmsson S. The perceived meaning of a (w)holistic view among general practitioners and district nurses in Swedish primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:781–820. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azzolini F, Pagnini C, Camellini L, Scarcelli A, Merighi A, Primerano AM, et al. Proposal of a new clinical index predictive of endoscopic severity in ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:246–251. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-1590-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seo M, Okada M, Yao T, Okabe N, Maeda K, Oh K. Evaluation of disease activity in patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis: comparisons between a new activity index and Truelove and Witts’ classification. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1759–1763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, Wismeijer JA, Van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. IBS-like symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission; relationships with quality of life and coping behavior. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:469–474. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000020506.84248.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keohane J, O’Mahony C, O’Mahony L, O’Mahony S, Quigley E, Shanahan F. Co-existence of IBS-related symptoms in patients with Crohn’s disease-A real association of a reflection of occult inflammation? Gastroenterology. 2007;134:A187. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhodes JM. The role of Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2007;56:610–612. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.111872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins PD, Schwartz M, Mapili J, Zimmermann EM. Is endoscopy necessary for the measurement of disease activity in ulcerative colitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]