Abstract

Full understanding of mechanisms that control seed dormancy and germination remains elusive. Whereas it has been proposed that translational control plays a predominant role in germination, other studies suggest the importance of specific gene expression patterns in imbibed seeds. Transgenic plants were developed to permit conditional expression of a gene encoding 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 6 (NCED6), a rate-limiting enzyme in abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis, using the ecdysone receptor-based plant gene switch system and the ligand methoxyfenozide. Induction of NCED6 during imbibition increased ABA levels more than 20-fold and was sufficient to prevent seed germination. Germination suppression was prevented by fluridone, an inhibitor of ABA biosynthesis. In another study, induction of the NCED6 gene in transgenic seeds of nondormant mutants tt3 and tt4 reestablished seed dormancy. Furthermore, inducing expression of NCED6 during seed development suppressed vivipary, precocious germination of developing seeds. These results indicate that expression of a hormone metabolism gene in seeds can be a sole determinant of dormancy. This study opens the possibility of developing a robust technology to suppress or promote seed germination through engineering pathways of hormone metabolism.

Keywords: embryo, endosperm, preharvest sprouting, testa

Seed germination is completed by the emergence of the embryo from the seed coat (1), and plants have evolved a number of strategies to regulate germination. Seeds of many species go through dormancy, a period during which germination is suppressed under conditions that are normally favorable for germination (2). Dormancy allows seeds to germinate in appropriate seasons or at locations suitable for seedling growth and further development.

Seed dormancy and germination are controlled primarily by the balance of abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellin (GA) (3). ABA is involved in the induction and maintenance of seed dormancy, whereas GA releases dormancy and induces germination. ABA and GA levels are determined by the relative rates of biosynthesis and deactivation of their chemical precursors and conjugates, the levels of which are mainly controlled by gene expression (4, 5). In contrast, hormone signal transduction is considered to be posttranslationally regulated. RGA-LIKE2 (RGL2), a repressor of seed germination, is subjected to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway after perception of GA by GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE 1 (GID1), a GA receptor (6, 7). ABA INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5), a germination repressor in the ABA signaling cascades that is affected by RGL2 (8), is also subjected to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (9). Interestingly, the direct target of RGA is XERICO, an H2-type RING protein that positively affects ABA accumulation (10). Thus, there is a feedback loop to the hormone metabolism pathways that balances the biosynthesis of ABA with its degradation, the outcome of which is an important determinant of dormancy and germination of seeds.

An objective of this study was to evaluate the role of expression of genes that control ABA production in germination of seeds. Earlier work supported the conclusion that germination is largely, or solely, based on translation of stored mRNAs and on functions of preexisting proteins in a study that used inhibitors of transcription and translation (11). On the other hand, data from studies that used transcriptome analyses support the suggestion that changes in gene expression are essential for release from dormancy and induction of germination-specific processes (12, 13).

We hypothesized that changing the expression of a key gene involved in synthesis of ABA during imbibition would be sufficient to modify hormone levels and germination of seeds. We tested this hypothesis by focusing on a key regulatory step of ABA biosynthesis, namely the cleavage of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoids to produce xanthoxin, catalyzed by 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenases (NCEDs) (14, 15). NCED genes have been isolated from many agricultural species including maize (Zea mays) (16), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (17), potato (S. tuberosum) (18), avocado (Persea americana) (19), and orange (Citrus sinensis) (20). In Arabidopsis thaliana, NCED6 and NCED9 are the major genes involved in ABA biosynthesis in seeds. NCED6 is expressed in the endosperm and NCED9 in the endosperm and embryo of developing seeds (14).

Genetic analyses of loss- or gain-of-function mutants in ABA biosynthesis suggested that both NCED6 and NCED9 are important for induction and maintenance of dormancy. Arabidopsis nced6 nced9 double mutants showed a decrease in seed ABA content and reduced dormancy (14). However, mutations in these genes affect seed development, and it is not clear whether dormancy/germination phenotypes are the consequence of gene expression during seed development or only during imbibition. Although expression during both stages is probably important for control of germination, it is important to separate the events of seed development and germination.

To cause expression of NCED in a narrow stage of development, we adapted the plant gene switch system (PGSS), a chemically induced gene expression system. PGSS is based on the ecdysone receptor (EcR) and methoxyfenozide (MOF) and is free of drawbacks of other systems (21–23). The PGSS was used to induce transcription of NCED6 or NCED9 in imbibed seeds and in developing seeds under conditions that promote vivipary, precocious germination in developing seeds. Expression in imbibed seeds increased ABA production and restricted seed germination; fluridone, an inhibitor of ABA synthesis, inhibited this process. NCED9 was less effective than NCED6 in reducing germination. Induction of NCED6 during seed development increased seed dormancy and reduced or eliminated precocious germination.

Results

Induction of NCED6 in Imbibed Seeds.

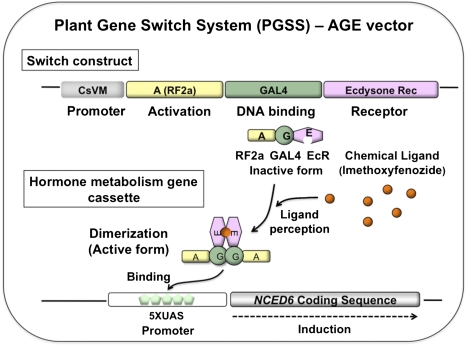

To test the hypothesis that induction of NCED6, a gene encoding the rate-limiting ABA biosynthesis enzyme 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (Fig. S1), suppresses seed germination, the coding region of NCED6 was cloned to the PGSS vector containing both the gene switch construct encoding the chimeric receptor protein AGE and the inducible promoter that is responsive to AGE upon addition of MOF (Fig. 1). Whereas the original VGE effector contains the VP16 activation domain from herpes simplex virus (V) (24), AGE (25) replaces the V domain with the activation domain from the rice bZIP protein RF2a (A) (26) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the plant gene switch system with the AGE vector used in this study. The EcR-based PGSS is an efficient, inducible system with a unique ligand that essentially meets many of the criteria for field application; furthermore, few significant drawbacks (e.g., toxicity of the ligand) of this system have been observed. The PGSS consists of three basic components. First is a receptor protein that responds to a suitable ligand to activate gene expression. The chimeric receptor protein AGE comprises an activation domain (A) from rice bZIP protein RF2a (26) (highlighted in yellow), the DNA-binding domain of yeast GAL4 protein (G; amino acids 1–147) (41) (highlighted in green), and the ecdysone-binding region from the EcR from the spruce budworm C. fumiferana (E; amino acids 206–539) (42) (highlighted in pink). Second is an inducible promoter that when bound with the receptor activates expression of a hormone metabolism gene (e.g., NCED6) linked with the promoter (5XUAS). Third is a ligand that acts as an inducer, MOF (22, 46) (highlighted in orange). MOF is the active compound of Intrepid2F, which has been approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency and was used in this study. CsVM, cassava vein mosaic virus promoter.

Wild-type A. thaliana Columbia-0 plants were transformed with Agrobacterium harboring AGE:NCED6 under the control of the cassava vein mosaic virus promoter (Fig. 1), a strong constitutive promoter. Twenty AGE:NCED6 transgenic lines were recovered, none of which exhibited phenotypes distinguishable from wild-type plants. Homozygous lines were isolated from five independent transgenic lines based on segregation of the antibiotic resistance trait and were used for further studies.

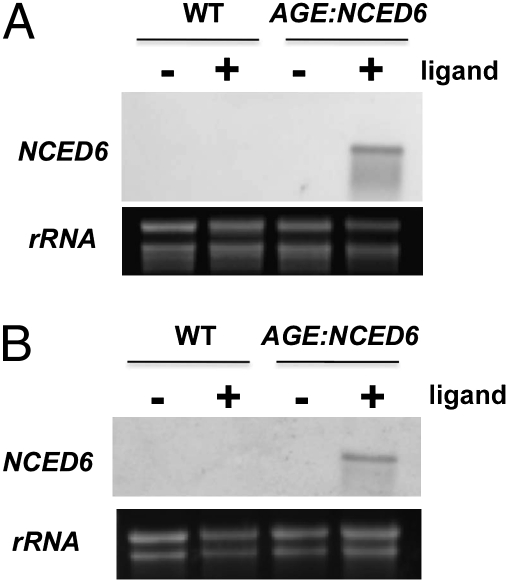

Induction of NCED6 in transgenic plants was effected by drenching the soil one time with watering solution containing Intrepid2F to ∼60 μM active ingredient MOF (Materials and Methods). Plants were generally in the 10-rosette leaf stage. Ligand application caused accumulation of transcripts of the NCED6 gene only in transgenic plants (Fig. 2A); transcripts were not detected in the absence of ligand, or in wild-type plants either in the presence or absence of ligand. These results demonstrated that the inducible AGE:NCED6 constructs functioned in the transgenic plants.

Fig. 2.

Induction of NCED6 in AGE:NCED6 transgenic lines. Expression of NCED6 was examined in WT and AGE:NCED6 transgenic rosettes after 48 h of soil drenching (A) and in seeds 29 h after imbibition (B) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of ligand. Equal loading images of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) are shown.

Wild-type and homozygous seeds from plant line 5-176 (Fig. S2) were imbibed for 29 h in the presence or absence of MOF, and total RNA was extracted and used for Northern blot analysis. NCED6 was observed in the AGE:NCED6 seeds treated with ligand (Fig. 2B), but not in noninduced seeds or in seeds from nontransgenic plants.

Modified Germination of Seeds That Produce NCED6.

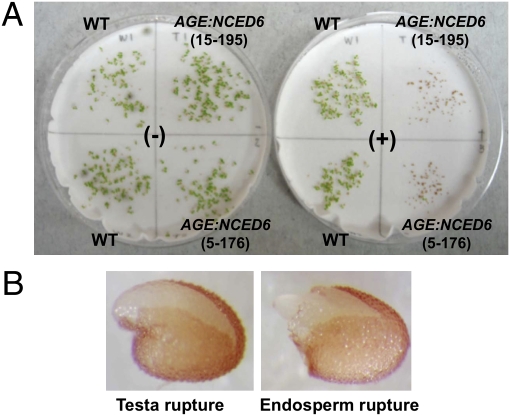

To establish the impact of ABA on germination, seeds were induced to produce NCED6 by bathing them in water containing MOF (Fig. 3A). As controls, seeds of nontransgenic plants were treated in a similar manner, and transgenic seeds were germinated in water. Germination was suppressed in transgenic seeds treated with MOF but not in AGE:NCED6 seeds in the absence of ligand or in nontransgenic seeds treated with ligand.

Fig. 3.

Induced suppression of germination of AGE:NCED6 seeds. (A) Photographs showing an example of germination suppression observed in AGE:NCED6 seeds. −, uninduced; +, induced by ligand. The ligand did not affect WT seed germination. (B) Photographs of induced AGE:NCED6 seeds that were arrested after testa rupture (Left) and endosperm rupture (Right) (see text for details).

Germination was suppressed in many individual seed lots from the five homozygous independent transgenic lines that were imbibed in water containing MOF, with near-complete suppression of radicle emergence and absence of seedling establishment (Fig. S2). The majority (77–89%) of the induced AGE:NCED6 seeds that failed to complete germination were arrested after testa rupture (Fig. 3B, Left). The remainder of arrested seeds (11–23% of seeds) exhibited endosperm rupture, although radicles did not continue to grow (Fig. 3B, Right). These events mimic germination suppression that occurs when exogenous ABA is added during germination (27).

It is known that Arabidopsis testa is impermeable to some small molecules (11, 28); thus, it is possible that MOF does not enter seeds in advance of rupture of the testa. In contrast, Arabidopsis endosperm seems to be permeable to the ligand, because many seeds were arrested immediately after testa rupture (Fig. 3B); furthermore, induction of NCED6 expression was detected at 29 h imbibition when most seeds had completed testa rupture but not radicle protrusion (Fig. 2B).

Altered ABA Levels in Seeds.

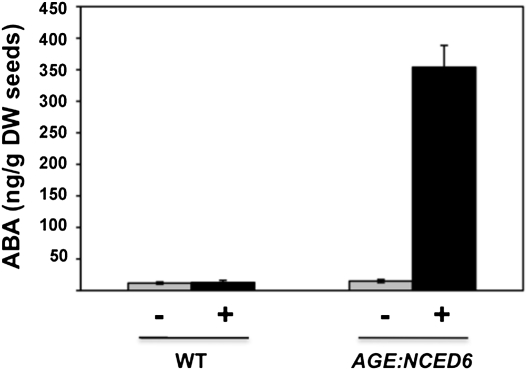

The suppression of germination that followed expression of the NCED6 gene was presumably caused by changes in ABA biosynthesis. This was confirmed by quantifying ABA levels in seeds using mass spectrometry. In the absence of MOF, ABA levels in both wild-type and AGE:NCED6 seeds were relatively low and similar to each other. In contrast, following application of the ligand, there was a marked increase in ABA in AGE:NCED6 seeds (Fig. 4). Indeed, the ABA levels in induced AGE:NCED6 seeds (Fig. 4) were equivalent to those reported in cyp707A2, a mutation that results in hyperdormant seeds (29). CYP707A2 encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylase (29), an enzyme that degrades ABA, and hyperdormancy in this line is due to an increase in the amount of ABA due to reduced amounts of the enzyme.

Fig. 4.

Increased ABA levels in induced AGE:NCED6 seeds. ABA levels in WT and AGE:NCED6 seeds incubated for 29 h in the absence (−) or presence (+) of ligand are shown. Data indicate average ± SD (n = 3). DW, dry weight.

The degree of induction of expression of the NCED6 gene was not established in this study, although increases in amounts of gene transcript were significant (Fig. 2). It is clear that induction of NCED6 by the gene switch was sufficient to cause large increases in ABA levels.

Recovery of Germination After Treatment with Fluridone.

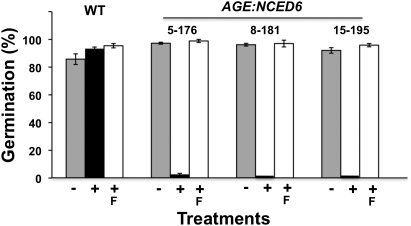

To confirm that inhibition of germination of induced AGE:NCED6 seeds was due to production of ABA, seeds were germinated in the presence of fluridone, a carotenoid biosynthesis inhibitor (30). Fluridone inhibits phytoene desaturase, a key enzyme in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway (31), upstream of the role of NCED6 in ABA biosynthesis (Fig. S1), and treating seeds with fluridone can reduce ABA synthesis (32). Seeds of plants containing the AGE:NCED6 gene were germinated with coapplication of MOF and fluridone to determine the effect on germination. As described above, the suppression of germination of induced AGE:NCED6 seeds was fully rescued by fluridone (Fig. 5) and seeds that were induced germinated and developed to seedlings, although they were etiolated due to the herbicidal effects of the chemical. These results support the conclusion that specific suppression of germination in seeds of AGE:NCED6 plants induced with MOF was dependent on ABA biosynthesis.

Fig. 5.

Suppression of germination in AGE:NCED6 seeds induced by MOF and recovery of germination by 10 μM fluridone, an inhibitor of ABA biosynthesis. Percentage germination of seeds of WT and three AGE:NCED6 lines (5-176, 8-181, and 15-195). −, uninduced; +, induced with ligand; F, fluridone treatment (+F, both ligand and fluridone treatments). Data from three experiments of 50–100 seeds per sample; average ± SD (n = 3).

Suppression of Germination in Nondormant Mutant Seeds.

Transgenic lines were also developed in a nondormant line of Arabidopsis, tt (transparent testa), to determine whether induction of ABA production could repress germination in this line. The tt mutants lack pigments in testa (28, 33): TT3 and TT4 encode dihydroflavonol 4-reductase and chalcone synthase, respectively; both enzymes are involved in biosynthesis of proanthocyanidin (PA) (34, 35). PA plays an essential role in imposing seed dormancy, and tt mutant seeds exhibit little dormancy (36). tt3 and tt4 were transformed with the AGE:NCED6 vector; however, relatively few transgenic lines were recovered from the tt lines, most likely due to hypersensitivity of tt seeds to sterilization and to the use of antibiotics during screening. However, most of the transgenic lines isolated showed clear response to induction by the ligand. The AGE:NCED6 seeds in both tt3 and tt4 backgrounds exhibited suppression of germination specifically in the presence of MOF (Fig. S3). The results demonstrated that germination of the extreme nondormant mutant can be suppressed by altering the expression of the NCED6 gene during imbibition.

Induction of NCED9, a Second Rate-Limiting Enzyme in ABA Biosynthesis.

NCED9 is another seed-specific NCED expressed in developing seeds (14). We generated and tested eight independent transgenic lines that contain an inducible AGE:NCED9 gene. Suppression of seed germination was observed in many but not all of these lines (about 57%), and suppression was incomplete in most lines (Fig. S4). The reason for differences in suppression between seeds that produce NCED6 versus those that produce NCED9 is not yet clear. Other studies have confirmed that NCED6 is specifically expressed in the endosperm of developing seeds whereas NCED9 is expressed in the endosperm and the peripheral regions of the embryo during seed development (14).

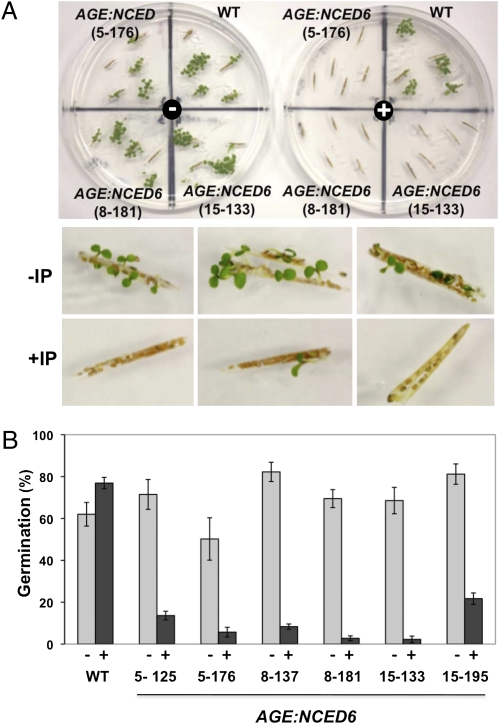

Suppression of Precocious Germination in Developing Seeds.

The induction experiments clearly indicate that an increased accumulation of NCED6 transcripts and concomitant increase in ABA levels can be a determinant of germination. We also induced NCED6 in developing seeds, focusing on its function to prevent vivipary. Preliminary experiments had indicated that the peak expression of NCED6 was during the long-green silique stage (Fig. S5) in Arabidopsis. Developing siliques of the AGE:NCED6 lines were treated or not treated with ligand under conditions that favor precocious germination. Germination from the developing seeds contained in green siliques of the AGE:NCED6 lines was effectively suppressed by treatment with MOF, whereas those incubated held under similar conditions but without MOF underwent precocious germination (Fig. 6). Suppression of vivipary was also observed in yellow-stage siliques, that is, those that are more mature (Fig. S6), when siliques were treated with MOF. These results indicated that increasing NCED6 gene expression significantly alters the dormancy of developing seeds.

Fig. 6.

Suppression of precocious germination in AGE:NCED6 siliques. (A) Immature green siliques incubated for 12 d on agar media. (Upper) WT and AGE:NCED6 lines (5-176, 8-181, and 15-133) incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of ligand. Note that the induced AGE:NCED6 siliques exhibit little germination. (Lower) Representative images of precocious germination in the absence of ligand (−IP) and suppression of precocious germination in the presence of ligand (+IP) in AGE:NCED6 siliques. (B) Results of precocious germination tests of WT and AGE:NCED6 siliques (three independent lines, two individual plants for each line), in the absence (−) or presence (+) of ligand. Data indicate average ± SD (n = 3).

Discussion

The role of ABA in inducing and maintaining seed dormancy is well-known; it is also well-known that NCED proteins are rate-limiting in ABA synthesis. However, direct evidence that NCED is involved in seed dormancy remained to be established. Mutants in which ABA degradation is prevented exhibit reduced seed germination (29), indicating that a specific level of ABA is necessary to maintain seed dormancy. Constitutive overexpression of NCED1 in tomato seeds suppressed seed germination; however, constitutive overexpression increased ABA levels in many plant tissues and caused undesirable phenotypes in plant development (37, 38). To alter ABA levels to specifically effect seed dormancy requires a tighter control of expression of an NCED gene(s). In this study, conditional expression was used to control the production of NCED.

Genes encoding A. thaliana NCED6 and NCED9 were expressed in A. thaliana using the EcR-based system and MOF was used to activate gene expression. The studies provided conclusive evidence that induction of NCED6 gene expression, and to a lesser degree NCED9, during imbibition led to high levels of ABA production, which in turn restricted seed germination. When the ABA synthesis inhibitor fluridone was administered concurrently with induction of gene expression, production of ABA was reduced and the amount of seed germination was increased. Similarly, inducing expression of NCED6 in detached siliques during seed development repressed vivipary, presumably by increasing production of ABA.

Other workers reported that inducing expression of a bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) NCED gene in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) seeds using the dexamethasone-inducible system resulted in incomplete suppression of germination (39). Incomplete suppression might result from expression of a heterologous NCED gene or incomplete penetration of the gene switch system that was used.

The outcomes of this study provide a foundation for developing technologies related to seed germination, for example, to reduce vivipary in agricultural species that produce partially dormant seeds. For example, preharvest sprouting can occur during wheat production if moist conditions are encountered late in the growing season (40). It is critical to understand the mechanisms of both suppression and promotion of seed germination and to develop technologies to control seed development, dormancy, and germination to reduce unwanted vivipary. Gene-switching technologies can be used to address this and similar problems in seed development.

There are multiple inducible gene expression systems other than the PGSS used in the current study. Some have been used successfully in experiments to modify seed germination (8). However, many systems use ligands that may not be readily adapted to applications in agricultural practices, such as steroid hormones or antibiotics. Although a moderate concentration of methoxyfenozide was used in these studies (a dilution of Intrepid2F to ∼62 μM MOF active ingredient), other experiments conducted using AGE:NCED6 seeds have indicated that the ligand can be diluted to 0.45 μM to suppress germination (Fig. S7). Intrepid2F has been approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA Regulation 62719-442) for field use as a receptor-specific insecticide, making use of this gene switch potentially relevant to use in agriculture. Furthermore, in addition to inducible expression, NCED6 expression during seed development can potentially be enhanced, for example by using other promoters, to cause spontaneous hyperdormancy and prevent preharvest sprouting.

Materials and Methods

Vector Construction and Plant Transformation.

The coding regions of NCEDs were ligated to the restriction sites in the AGE gene switch vector (25). Details of NCED amplification and ligation are described in SI Materials and Methods. The AGE vector contains the activation domain from rice bZIP protein RF2a (26), the DNA-binding domain of yeast GAL4 protein (G; amino acids 1–147) (41), and the ecdysone-binding region from the EcR from the spruce budworm Cloristoneura fumiferana (E; amino acids 206–539) (42) (Fig. 1). The sequences in the transformation vectors were verified again (termed AGE:NCED6 and AGE:NCED9). The transformation vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation, and the resulting strains were used to transform Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia-0 by the floral dip method (43).

Induction Experiments.

For the induction of AGE:NCED6 plants at ∼10-rosette stages, diluted (10,000×) Intrepid2F (Dow AgroSciences) solution that contained 62 μM MOF as an active ingredient was applied directly to the soil in pots containing Arabidopsis seedlings by drenching. Seedlings were harvested 2 d after induction and frozen at −80 °C before RNA extraction. For the induction experiments in imbibed seeds, seeds were placed in 9-cm plastic Petri dishes on two layers of filter paper (no. 2; Whatman) moistened with 3.5 mL water or Intrepid2F (10,000×) and incubated at 4 °C for 3 d and at 22 °C for 29 h (gene expression analysis) or 5 d (germination tests). For germination recovery, 10 μM fluridone was included with Intrepid2F.

Gene Expression Analyses.

Methods for gene expression analysis are described in SI Materials and Methods.

ABA Quantification.

ABA was quantified at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Facility. The method has been published previously (44), but was modified to ABA. Details are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Precocious Germination Experiments.

Developing siliques at the long-green stage (Fig. S5) were collected, slightly opened at the replum-valve margin using a surgical blade, sterilized with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol for 1 min and 25% bleach for 10 min, and then plated on 0.7% (wt/vol) agar containing 1% (wt/vol) sucrose and Murashige and Skoog salt (45), with or without Intrepid2F (10,000×). For three independent homozygous AGE:NCED6 lines and wild type, 10 siliques from each of three individual plants were divided into two groups of five, which were plated in the presence or absence of ligand, respectively. Germination was examined after 12 d of incubation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Isabelle Debeaujon, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, France, for her advice on tt mutants, and Natalya Goloviznina and Theresa Nguyen, Oregon State University, for their assistance in microscopy and precocious germination experiments. This work was supported by a Fundación Séneca Fellowship (to C.M.-A.) and National Science Foundation Grant IBN-0237562 (to H.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1112151108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nonogaki H, Bassel GW, Bewley JD. Germination—Still a mystery. Plant Sci. 2010;179:574–581. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bewley JD, Black M. In: Seeds: Physiology of Development and Germination. Bewley JD, Black M, editors. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 199–271. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seo M, Nambara E, Choi G, Yamaguchi S. Interaction of light and hormone signals in germinating seeds. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;69:463–472. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9429-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi S, Kamiya Y, Nambara E. In: Seed Development, Dormancy and Germination. Bradford KJ, Nonogaki H, editors. Oxford: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 224–247. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seo M, et al. Regulation of hormone metabolism in Arabidopsis seeds: Phytochrome regulation of abscisic acid metabolism and abscisic acid regulation of gibberellin metabolism. Plant J. 2006;48:354–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ariizumi T, Murase K, Sun TP, Steber CM. Proteolysis-independent downregulation of DELLA repression in Arabidopsis by the gibberellin receptor GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2447–2459. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ariizumi T, Steber CM. Seed germination of GA-insensitive sleepy1 mutants does not require RGL2 protein disappearance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:791–804. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piskurewicz U, et al. The gibberellic acid signaling repressor RGL2 inhibits Arabidopsis seed germination by stimulating abscisic acid synthesis and ABI5 activity. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2729–2745. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, Kinoshita N, Chua N-H. AFP is a novel negative regulator of ABA signaling that promotes ABI5 protein degradation. Genes Dev. 2003;17:410–418. doi: 10.1101/gad.1055803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zentella R, et al. Global analysis of DELLA direct targets in early gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3037–3057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajjou L, et al. The effect of α-amanitin on the Arabidopsis seed proteome highlights the distinct roles of stored and neosynthesized mRNAs during germination. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1598–1613. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.036293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadman CSC, Toorop PE, Hilhorst HWM, Finch-Savage WE. Gene expression profiles of Arabidopsis Cvi seeds during dormancy cycling indicate a common underlying dormancy control mechanism. Plant J. 2006;46:805–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finch-Savage WE, Cadman CSC, Toorop PE, Lynn JR, Hilhorst HWM. Seed dormancy release in Arabidopsis Cvi by dry after-ripening, low temperature, nitrate and light shows common quantitative patterns of gene expression directed by environmentally specific sensing. Plant J. 2007;51:60–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefebvre V, et al. Functional analysis of Arabidopsis NCED6 and NCED9 genes indicates that ABA synthesized in the endosperm is involved in the induction of seed dormancy. Plant J. 2006;45:309–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nambara E, Marion-Poll A. Abscisic acid biosynthesis and catabolism. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:165–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan BC, Schwartz SH, Zeevaart JAD, McCarty DR. Genetic control of abscisic acid biosynthesis in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12235–12240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burbidge A, et al. Characterization of the ABA-deficient tomato mutant notabilis and its relationship with maize Vp14. Plant J. 1999;17:427–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Destefano-Beltrán L, Knauber D, Huckle L, Suttle JC. Effects of postharvest storage and dormancy status on ABA content, metabolism, and expression of genes involved in ABA biosynthesis and metabolism in potato tuber tissues. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;61:687–697. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-0042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chernys JT, Zeevaart JAD. Characterization of the 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene family and the regulation of abscisic acid biosynthesis in avocado. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:343–353. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.1.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodrigo M-J, Alquezar B, Zacarías L. Cloning and characterization of two 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase genes, differentially regulated during fruit maturation and under stress conditions, from orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck) J Exp Bot. 2006;57:633–643. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padidam M. Chemically regulated gene expression in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koo JC, Asurmendi S, Bick J, Woodford-Thomas T, Beachy RN. Ecdysone agonist-inducible expression of a coat protein gene from tobacco mosaic virus confers viral resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2004;37:439–448. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavva VS, Dinkins RD, Palli SR, Collins GB. Development of a tightly regulated and highly inducible ecdysone receptor gene switch for plants through the use of retinoid X receptor chimeras. Transgenic Res. 2007;16:599–612. doi: 10.1007/s11248-006-9054-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalrymple MA, McGeoch DJ, Davison AJ, Preston CM. DNA sequence of the herpes simplex virus type 1 gene whose product is responsible for transcriptional activation of immediate early promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:7865–7879. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.21.7865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ordiz MI, Yang J, Barbazuk WB, Beachy RN. Functional analysis of the activation domain of RF2a, a rice transcription factor. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010;8:835–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai S, et al. Functional analysis of RF2a, a rice transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36396–36402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller K, Tintelnot S, Leubner-Metzger G. Endosperm-limited Brassicaceae seed germination: Abscisic acid inhibits embryo-induced endosperm weakening of Lepidium sativum (cress) and endosperm rupture of cress and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:864–877. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Debeaujon I, Léon-Kloosterziel KM, Koornneef M. Influence of the testa on seed dormancy, germination, and longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:403–414. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kushiro T, et al. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP707A encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylases: Key enzymes in ABA catabolism. EMBO J. 2004;23:1647–1656. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartels PG, Watson CW. Inhibition of carotenoid synthesis by fluridone and norflurazon. Weed Sci. 1978;26:198–203. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamovitz D, Sandmann G, Hirschberg J. Molecular and biochemical characterization of herbicide-resistant mutants of cyanobacteria reveals that phytoene desaturation is a rate-limiting step in carotenoid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17348–17353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grappin P, Bouinot D, Sotta B, Miginiac E, Jullien M. Control of seed dormancy in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia: Post-imbibition abscisic acid synthesis imposes dormancy maintenance. Planta. 2000;210:279–285. doi: 10.1007/PL00008135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Debeaujon I, Koornneef M. Gibberellin requirement for Arabidopsis seed germination is determined both by testa characteristics and embryonic abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:415–424. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirley BW, Hanley S, Goodman HM. Effects of ionizing radiation on a plant genome: Analysis of two Arabidopsis transparent testa mutations. Plant Cell. 1992;4:333–347. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feinbaum RL, Ausubel FM. Transcriptional regulation of the Arabidopsis thaliana chalcone synthase gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1985–1992. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Debeaujon I, Lepiniec L, Pourcel L, Routaboul JM. In: Seed Development, Dormancy and Germination. Bradford KJ, Nonogaki H, editors. Oxford: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson AJ, et al. Ectopic expression of a tomato 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene causes over-production of abscisic acid. Plant J. 2000;23:363–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan J, Hill L, Crooks C, Doerner P, Lamb C. Abscisic acid has a key role in modulating diverse plant-pathogen interactions. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1750–1761. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.137943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin X, Zeevaart JAD. Overexpression of a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia increases abscisic acid and phaseic acid levels and enhances drought tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:544–551. doi: 10.1104/pp.010663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerjets T, Scholefield D, Foulkes MJ, Lenton JR, Holdsworth MJ. An analysis of dormancy, ABA responsiveness, after-ripening and pre-harvest sprouting in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) caryopses. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:597–607. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laughon A, Gesteland RF. Primary structure of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae GAL4 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:260–267. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.2.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perera SC, et al. An analysis of ecdysone receptor domains required for heterodimerization with ultraspiracle. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1999;41:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Q, Zhang B, Hicks LM, Wang S, Jez JM. A liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry-based assay for indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase. Anal Biochem. 2009;390:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padidam M, Gore M, Lu DL, Smirnova O. Chemical-inducible, ecdysone receptor-based gene expression system for plants. Transgenic Res. 2003;12:101–109. doi: 10.1023/a:1022113817892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.