Abstract

Hairy roots and suspension cell cultures are commonly used in deciphering different problems related to the biochemistry and physiology of plant secondary metabolites. Here, we address about the issue of possible differences in the profiles of flavonoid compounds and their glycoconjugates derived from various plant materials grown in a standard culture media. We compared profiles of flavonoids isolated from seedling roots, hairy roots, and suspension root cell cultures of a model legume plant, Medicago truncatula. The analyses were conducted with plant isolates as well as the media. The LC/MS profiles of target natural products obtained from M. truncatula seedling roots, hairy roots, and suspension root cell cultures differed substantially. The most abundant compounds in seedlings roots were mono- and diglucuronides of isoflavones and/or flavones. This type of glycosylation was not observed in hairy roots or suspension root cell cultures. The only recognized glycoconjugates in the latter samples were glucose derivatives of isoflavones. Application of a high-resolution mass spectrometer helped evaluate the elemental composition of protonated molecules, such as [M + H]+. Comparison of collision-induced dissociation MS/MS spectra registered with a quadrupole time-of-flight analyzer for tissue extracts and standards allowed us to estimate the aglycone structure on the basis of the pseudo-MS3 experiment. Structures of these natural products were described according to the registered mass spectra and literature data. The analyses conducted represent an overview of flavonoids and their conjugates in different types of plant material representing the model legume, M. truncatula.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11306-011-0287-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aglycone, Collision-induced dissociation, Electrospray, Flavone, Glycoconjugate, Isoflavone, Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, Medicago truncatula, Metabolite profiling

Introduction

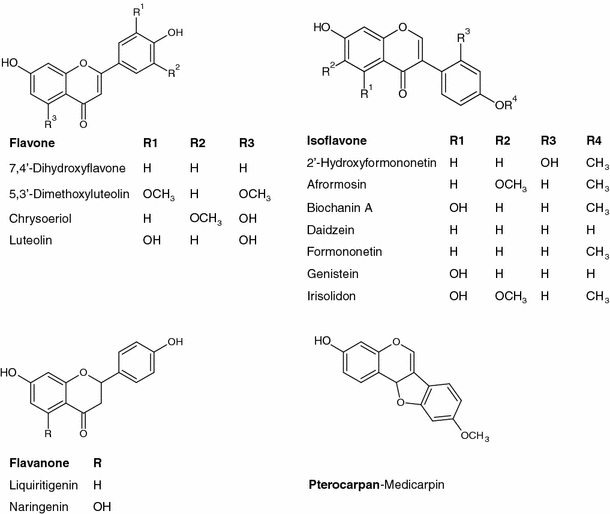

Flavonoids and their glycoconjugates synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway are a very interesting group of secondary metabolites. This is due to a wide spectra of biological activities of these compounds and also participation in many physiological and biochemical processes (Schijlen et al. 2004; Lepiniec et al. 2006; Bovy et al. 2007; Veitch and Grayer 2008; Veitch 2009; Paredes-Lopez et al. 2010). Flavonoids represent numerous structures as a consequence of the phenolic ring B position as well as various substitutions of hydroxyl groups (Fig. 1). In addition, glycosylation and further acylation of aglycones is associated with the possible occurrence of isomeric compounds. Because of this, by 2006, over 6,000 different phenolic structures have been reported (Stobiecki and Kachlicki 2006; Veitch and Grayer 2008). Profiling of secondary metabolites is a challenging task from an analytical point of view. Difficulties with the interpretation of the registered data in liquid chromatography together with mass spectrometry analyses (LC/ESI/MS/MS) are as follows: (1) the presence of isobaric compounds with the same molecular weight and different elemental composition and (2) the isomers of natural products with different substitutions of sugar moieties or various patterns of acylating groups on the sugar moieties and isomerization of the aglycones (e.g. flavones and isoflavones).

Fig. 1.

Structures of flavonoid aglycones in the M. truncatula root tissue

Profiling of flavonoid glycoconjugates using mass spectrometry is a well-established analytical method and several papers have been published on this subject (for review, see: Prasain et al. 2004; Fossen and Andersen 2006; Stobiecki and Kachlicki 2006; March and Brodbelt 2008). However, a problem occurring with unambiguous identification of the target compounds is still a difficult task. Profiles of flavonoids and their conjugates in M. truncatula tissues or suspension cell cultures were published in several papers dedicated especially to the (i) role of this class of secondary metabolites in plant interactions with pathogenic microorganisms or their elicitors (Broeckling et al. 2005; Naoumkina et al. 2007; Farag et al. 2007, 2008, 2009; Jasiński et al. 2009), (ii) symbiosis with rhizobia (Zhang et al. 2009) and (iii) interactions with mycorrhizal fungi (Schliemann et al. 2008).

We address the question of phenolic compositions originating from various types of plant materials (tissues). During the analyses conducted, we observed substantial differences in the compositions of flavonoid glycoconjugates, especially in the seedling roots and suspension cell or hairy root cultures obtained from the root tissues. In this paper, we would like to present differences in the flavonoid profiles that vary with the source of plant material, from which the samples were prepared. We discuss problems related to the structural characterization of target compounds registered with different mass spectrometric techniques after separation of mixtures on the UPLC system.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and standards

Solvents used for extraction and LC/MS analyses were of analytical or LC/MS grade obtained from Baker (Łódź, Poland) and Sigma-Aldrich (Poznań, Poland). Saccharose, other organic compounds and microelements added to media were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poznań, Poland). For structural confirmation, the following standards were applied: daidzein, formononetin, genistein, biochanin A, daidzein 7-O-glucoside and genistein 7-O-glucoside from Extrasynthese (Genay, France).

Plant material

Medicago seedlings (Jemalong J5) were germinated in water-saturated Whatman discs in Petri plates and were grown under controlled greenhouse conditions with an average temperature of 22°C, 50% humidity, and a 16 h photoperiod. Seven-day-old Medicago seedlings were transferred to the modified liquid Fahraeus medium (Boisson-Dernier et al. 2001), and after 24 h, roots and medium were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

The Medicago suspension cell culture was initiated from M. truncatula roots and was kept in the dark at 22°C on an orbital shaker (150 rpm). The cell suspension was grown in an MSO/2 medium supplemented with saccharose (30 g/l), 2, 4D (2 mg/l), kinetin (0.25 mg/l) and casein hydrolysate (250 mg/l) and was subcultured every 2 weeks at a 1:2 dilution in a fresh medium. Seven-day-old cultures were used for the analysis.

Hairy root cultures were initiated from Medicago truncatula after being infected with the Agrobacterium rhizogenes Arqua1 strain (Quandt et al. 1993). Hairy root cultures were grown in the dark at 22°C in a modified Fahraeus medium supplemented with saccharose (10 g/l), mio-inositol (100 mg/l), thiamine (10 mg/l), pyridoxine (1 mg/l), biotin (1 mg/l), nicotinic acid (1 mg/l), glycine (2 mg/l), and indoleacetic auxin (0.5 mg/l).Three-week-old hairy root cultures were transferred to a fresh liquid medium and after 48 h, both hairy roots and media were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Extraction of plant material

For the structural elucidation of flavonoid glycoconjugates, the frozen plant materials (200 mg seedling roots, 250 ± 50 mg hairy roots and 1 g root cell suspension culture) were homogenized in 80% methanol (with adapted volumes of 4, 4, 12 ml, respectively), and the suspension was placed in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min. The extract was centrifuged and the supernatant was transferred to a new screw-capped tube. The solvent was evaporated in a vacuum concentrator model, Savant SPD 121P Thermo Electron Corporation (Waltham, USA). During this procedure, the tube was placed in a tray rotating in a vacuum at room temperature. Dried extract samples were dissolved in 80% methanol in water (0.5 ml) and immediately subjected to the LC/CID/MS/MS analyses.

Solid-phase extraction of culure media

Solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges (400 mg of C18 silica gel) were fitted into stopcocks and connected to a vacuum manifold. The sorbent was conditioned with 5 ml of methanol followed by 5 ml water. Care was taken that the sorbent did not become dry during conditioning. The corresponding sample media were transferred to the SPE column reservoir. With the stopcocks opened and the vacuum turned on, the samples were loaded onto the column. The vacuum pressure was gradually increased to maintain a constant flow rate (about 1 ml/min) throughout the loading process. After sample addition, the column was washed with 5 ml of water. Finally, the phenolics were eluted with 4 ml of 100% methanol.

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

Analyses of plant extract samples were performed with Agilent (Waldbronn, Germany) RR 1200 SL system (binary pump SL, diode array detector G1315C Starlight and automatic injector G1367C SL) connected to a micrOToF-Q mass spectrometer model from Bruker Daltonics (Bremen, Germany).

Analyses were carried out using Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 columns (Agilent) with a size and granulation of 2.1 × 100 mm2 and 1.8 μm, respectively. Chromatographic separation was performed at a 0.5 ml/min flow rate using mixtures of two solvents: A (99.5% H2O/0.5% formic acid v/v) and B (99.5% acetonitrile/0.5% formic acid v/v) with a 3:2 split of the column effluent, so 0.2 ml/min was delivered to the ESI ion source. The elution steps were as follows: 0–5 min linear gradient from 10 to 30% of B, 5–12 min isocratic at 30% of B, 12–13 min linear gradient from 30–95% of B, and 13–15 min isocratic at 95% of B. After returning back to the initial conditions, the equilibration was achieved after 4 min.

The micrOToF-Q mass spectrometer consisted of an ESI source operating at a voltage of ±4.5 kV, nebulization with nitrogen at 1.2 bar, and dry gas flow of 8.0 l/min at a temperature of 220°C. The instrument was operated using the program micrOTOF control ver. 2.3, and data were analyzed using the Bruker data analysis ver. 4 package.

The system was calibrated externally using the calibration mixture containing sodium formate clusters. Additional internal calibration was performed for every run by injection of the calibration mixture using the diverter valve during the LC separation. All calculations were done with the HPC quadratic algorithm. Such a calibration gave at least 5 ppm accuracy.

Targeted MS/MS experiments were performed using a collision energy ranging from 10 to 25 eV, depending on the molecular masses of compounds. The instrument operated at a resolution higher than 15,000 FWHM (full width at half maximum). According to the results of preliminary experiments, the spectra were recorded in the targeted mode within the m/z mass range of 50–1500. Metabolite profiles were registered in the positive and negative ion modes. In pseudo-MS3 experiments to increase fragmentaion of protonated molecules [M + H]+, the ionization potential was also controlled.

For identification of the compounds, the instrument operated in the CID MS/MS mode and single-ion chromatograms for exact masses of [M + H]+ ions (±0.005 Da) were recorded.

Results and discussion

Target profiling and identification of flavonoid glycoconjugates in the extracted samples from seedling roots of M. truncatula, hairy roots, and the suspension root cell culture were exclusively based on LC retention times and high-resolution mass spectra. The latter were registered in the MS and CID MS/MS (collision-induced dissociation tandem mass spectrometry analyses) modes performed with hybrid quadruple and time-of-flight analyzers in the positive and negative ion modes. However, it should be noted that mass spectra of malonylated isoflavone glucosides were not informative because of the intense fragmentation of the deprotonated molecules [M−H]–. Due to the elimination of the neutral CO2 molecules, in many mass spectra collected in the negative ion mode, [M−H]– ions were present at a very low abundance or were not registered at all. In the source collision, the induced dissociation energy (cone voltage) was an important parameter in this case (Muth et al. 2008). The elemental composition of ions was estimated on the basis of the MS m/z values registered to the fourth decimal point. The accuracy was better than 5 ppm at a resolution above 15,000 FWHM (full width at half maximum). Based on this fact, the structures of consecutively eluted compounds were proposed.

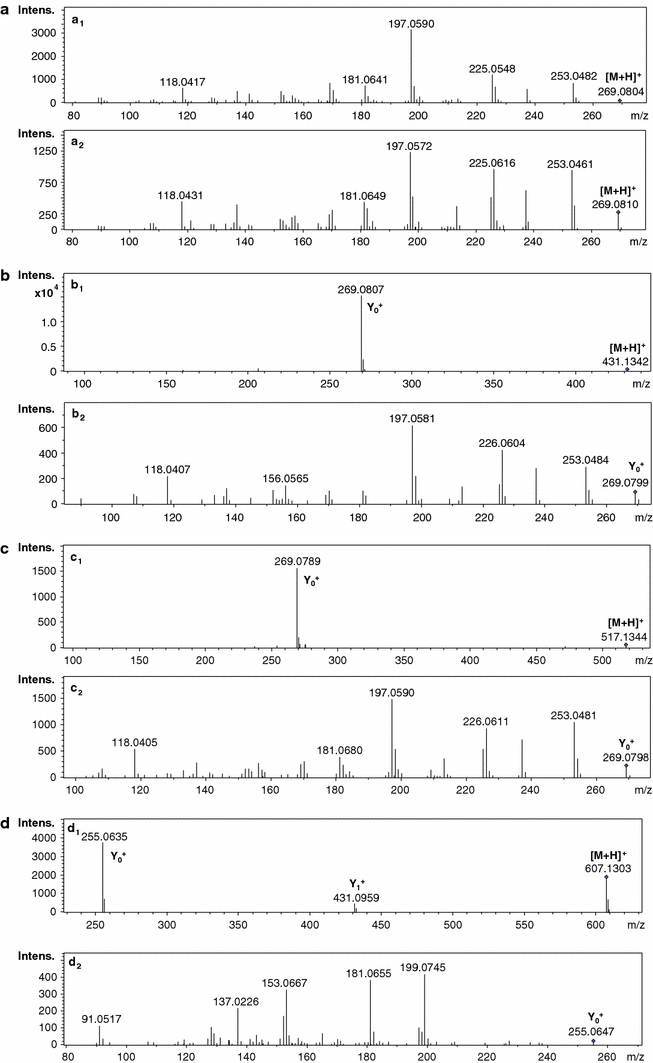

Structures of flavonoid aglycones present in the M. truncatula tissue extracts are presented in Fig. 1. Due to the presence of isomeric and isobaric derivatives of flavones and isoflavones in some cases, information obtained from registered MS and CID MS/MS spectra allowed only tentative identification of the target compounds. Estimation of glycosidic bonds between sugars and positions of sugars on the aglycone molecule was not possible. Standards of some isoflavone aglycones and their glucosides were used (see sect.2). Data obtained during pseudo-MS3 experiments at an increased ionization potential at entrance slits to the MS analyzer permitted us to identify in some cases the structures of the aglycone of the recognized flavonoid glycoconjugates (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mass spectra of chosen compounds identified in M. truncatula tissue: formononetin-CID MS/MS spectra: MS2 spectrum of the formononetin standard (a 1); MS2 spectrum of formononetin 49 (free aglycone) present in the medium of the hairy root culture (a 2); formononetin 7-O-glucoside 30 present in the extract of the seedling root-CID MS/MS spectra: MS2 spectrum of [M + H]+ at m/z 431 (b 1); and the pseudo-MS3 spectrum of Y0 + ion at m/z 269-formononetin aglycone (b 2); malonylated formononetin 7-O-glucoside 39 in the extract of the hairy root culture-CID MS/MS spectra: MS2 spectrum of [M + H]+ at m/z 517 (c 1) and the pseudo-MS3 spectrum of Y0 + ion at m/z 269-formononetin aglycone (c 2); daidzein 7-O-glucuronopyranosyl-O-glucuronopyranoside 2 present in the extract of the seedling root-CID MS/MS spectra: MS2 spectrum of [M + H]+ at m/z 607 (d 1) and the pseudo-MS3 spectrum of Y0 + ion at m/z 255 (daidzein aglycone) (d 2)

To register informative CID MS/MS spectra of [M + H]+ ions of the target compounds in the analyzed samples, potentials applied at the entrance slits of the MS analyzer and energy of collisions were adjusted. This was performed for all target compounds present in the analyzed extracts and these parameters depended on the molecular masses of the compounds eluted from the LC column at defined retention times. We profiled also the target compounds in a media of the suspension cell cultures and hairy root cultures. In some cases, only tentative identification of the compounds was possible based on the data obtained in CID MS/MS spectra and literature dedicated to the natural products of M. truncatula (Broeckling et al. 2005; Kowalska et al. 2007; Farag et al. 2007, 2008, 2009; Jasiński et al. 2009; Marczak et al. 2010).

Substantial differences in a composition of flavonoid glycoconjugates were observed among the samples obtained from seedling roots, hairy roots, and suspension root cell cultures. However, it was not possible for MS2 and pseudo-MS3 spectra to define the structures of all aglycones present in the analyzed samples. This was due to the low intensities of ions created for some target compounds. The reason for this might be that analyses were performed directly on the extracts obtained from root tissues. The presence of matrix compounds possibly decreased the quality of the registered spectra because of competition from the target secondary metabolites with the matrix compounds for ionization. The main difference between various tissues of M. truncatula was due to the presence of five monopyranoglucoronides (4, 9, 17, 18 and 23) and six diglucuronides (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7) in the seedling root extracts. Derivatives of dipyranoglucoronides acylated with ferrulic or coumaric acids were also present in the seedling samples. Among them, there were positional isomers with the acyl group substituted at different hydroxyl groups of sugar moieties: 10, 11, 14, 15, 19, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 32, 35 and 37. Genistein feruoyl glucuronopyranosyl-glucuronopyranoside possessed five isomers: 21, 26, 29, 32, 37 (Fig. 3). Differentiation of feruolyl group substitution on sugar rings was not possible in the registered CID MS/MS spectra. Daidzein feruoyl glucuronopyranosyl-glucuronopyranoside had four isomers 10, 14, 19, 26, which were separated and identified in the root extract sample. Presence of glycoconjugates substituted with glucuronic acid moieties was supported by earlier studies performed on leaves from M. truncatula (Marczak et al. 2010). Product ions observed in the CID MS/MS spectra followed the fragmentation pattern observed for the glucoronides identified in M. truncatula leaves. Mass spectra registered in the negative ion mode confirmed the obtained structural data (supplementary data in Figs. 1–10). The conjugates with glucuronic acid molecules were not present in the samples obtained from cultured suspension cells or hairy roots. From pseudo-CID-MS3 spectra of aglycone ions (Y0 1+), we suggest that aglycones of the diglucoronides were as follows: daidzein, genistein and luteoline. The presence of these compounds was not reported earlier in M. truncatula roots or root cell cultures (Schliemann et al. 2008; Farag et al. 2007, 2008, 2009). Differentiation between pairs of positional isomers (daidzein and 4′,7-dixydroxyflavone, apigenin and genistein, or luteolin and 2′-hydroxyformononetin) was not possible for each recognized compound in the samples. In addition to the previously mentioned flavonoid, diglucoronides and their acylated derivatives, the malonylated biochanin A diglucoside 25 and other monoglucosides of flavones and isoflavones 8, 12, 23, 30, 33 were recognized in the seedling root tissues. Glucosides were also present as malonylated derivatives 16, 20, 27, 31, 34, 36, 38-42 (see Table 1). Some malonylated isoflavone glucosides were identified as positional isomers. The main difference between leaf and root tissues of M. truncatula was that the aglycones of the leaf glucuronides were identified as flavones (Kowalska et al. 2007: Marczak et al. 2010), whereas in roots, these were identified as two unique isoflavones. On the other hand, it should be noted that pyranoglucuronides were more abundant in the extracts than the identified flavonoid glucosides and their malonylated derivatives (see supplementary data).

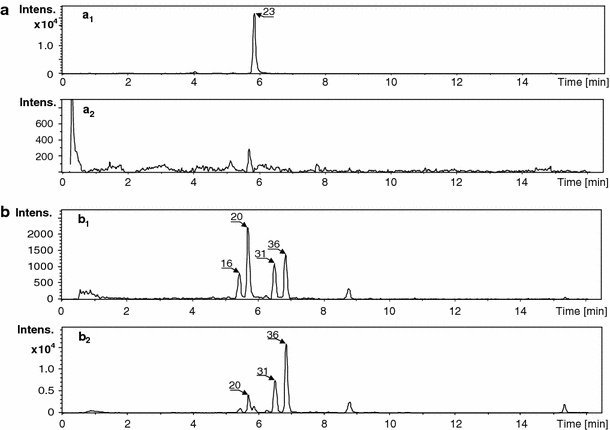

Fig. 3.

Single-ion chromatograms of [M + H]+ ions: chrysoeriol 7-O-glucuronopyranoside-23 at m/z 477 registered with an accuracy of ± 0.05 m/z: present in M. truncatula extracts: cell suspension (a 1) and hairy root (a 2) cultures; malonylated (I + II) 2′-hydroxyformononetin-7-O-glucoside-16, 20 and malonylated (I + II) biochanin A 7-O-glucoside-31, 36, [M + H]+ at m/z 533 registered with an accuracy of ± 0.05 m/z: present in M. truncatula extracts: cell suspension (b 1) and hairy root (b 2) cultures

Table 1.

Flavonoids and their glycoconjugates identified in roots, hairy root cultures and root cell cultures of M. truncatula

| No | Compound and formula1 | Rt (min) | m/z [M + H]+ calculated | Precursor and product ions [m/z] in CID MS/MS spectra2 | Presence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root | Hairy root culture | Root cell suspension culture | |||||

| 1 | Daidzein GlcAGlcA (I)-C27H26O16 a | 3.3 | 607.1294 | 607.1288 → 431.0904 → 255.0640 | + | − | − |

| 2 | Daidzein GlcAGlcA (II)-C27H26O16 a | 3.5 | 607.1294 | 607.1297 → 431.0904 → 255.0638 | + | − | − |

| 3 | Luteolin GlcAGlcA (I)-C27H26O18 a | 3.8 | 639.1192 | 639.1183 → 463.0895 → 287.0559 | + | − | − |

| 4 | 4′,7-O-Dihydroxyflavone GlcA-C21H18O10 b | 4.0 | 431.0973 | 431.0967 → 255.0642 | + | − | − |

| 5 | Genistein GlcAGlcA-C27H26O17 a | 4.4 | 623.1243 | 623.1208 → 447.0925 → 271.0592 | + | − | − |

| 6 | Luteolin GlcAGlcA (II)-C27H26O18 a | 4.5 | 639.1192 | 639.1179 → 463.0892 → 287.0553 | + | − | − |

| 7 | Genistein GlcAGlcA (II)-C27H26O17 a | 4.7 | 623.1243 | 623.1208 → 447.0925 → 271.0592 | + | − | − |

| 8 | Luteolin Glc (I) - C21H20O11 a | 4.8 | 449.1078 | 449.1084 → 287.0538 | + | + | − |

| 9 | Luteolin GlcA-C21H18O12 a | 4.9 | 463.0871 | 463.0890 → 287.0540 | + | + | − |

| 10 | Daidzein FerGlcAGlcA (I)-C37H34O19 a | 5.0 | 783.1767 | 783.1749 → 431.0931 → 255.0645 → 353.0859 | + | − | − |

| 11 | Daidzein CouGlcAGlcA (I) - C36H32O18 b | 5.0 | 753.1661 | 753.1663 → lack of product ions in MSn spectra | + | − | − |

| 12 | Luteolin Glc-C21H20O11 a | 5.1 | 449.1078 | 449.1621 → 287.0557 | + | + | − |

| 13 | Daidzein MalGlc-C24H22O12 b | 5.2 | 503.1104 | 503.1109 → 255.0638 | + | + | + |

| 14 | Daidzein FerGlcAGlcA (II)-C37H34O19 b | 5.3 | 783.1767 | 783.1760 → 431.0937 → 255.0641 → 353.0865 | + | − | − |

| 15 | Daidzein CouGlcAGlcA (II)-C36H32O18 b | 5.4 | 753.1661 | 753.1663 → 431.0931 → 255.0653 → 323.0752 | + | − | − |

| 16 | 2′-Hydroxyformononetin MalGlc (I)-C25H24O13 b | 5.4 | 533.1290 | 533.1291 → 285.0769 | + | − | − |

| 17 | Daidzein GlcA-C21H18O10 b | 5.5 | 431.0973 | 431.0981 → 255.0649 | − | − | + |

| 18 | Genistein GlcA-C21H18O11 a | 5.6 | 447.0922 | 447.0931 → 271.0587 | + | − | − |

| 19 | Daidzein FerGlcAGlcA (III)-C37H34O19 b | 5.7 | 783.1767 | 783.1777 → 431.0921 → 255.0643 → 353.0855 | + | − | − |

| 20 | 2′-Hydroxyformononetin Mal Glc (II)-C25H24O13 b | 5.7 | 533.1290 | 533.1287 → 285.0764 | + | + | − |

| 21 | Genistein FerGlcAGlcA (I)-C37H34O20 a | 5.7 | 799.1716 | 799.1712 → 447.0926 → 271.0601 → 353.0876 | + | − | − |

| 22 | Daidzein CouGlcAGlcA (III)-C36H32O18 b | 5.8 | 753.1661 | 753.1656 → 431.0927 → 255.0646 → 323.0752 | + | − | − |

| 23 | Chrysoeriol GlcA-C22H20O12 a | 5.8 | 477.1028 | 477.1019 → 301.0718 | + | − | − |

| 24 | Genistein CouGlcAGlcA (I)-C36H32O19 a | 5.8 | 769.1611 | 769.1589 → 447.0922 → 271.0598 → 323.0769 | + | − | − |

| 25 | Biochanin A MalGlcGlc-C31H34O18 b | 5.8 | 695.1818 | 695.1829 → 533.1246 → 447.0915 → 285.0771 | − | + | − |

| 26 | Daidzein FerGlcAGlcA (IV)-C37H34O19 b | 5.9 | 783.1767 | 783.1777 → 431.0921 → 255.0641 → 353.0855 | + | − | − |

| 26 | Genistein FerGlcAGlcA (II)-C37H34O20 a | 6.1 | 799.1716 | 799.1714 → 447.0928 → 271.0601 → 353.0876 | + | − | − |

| 27 | Genistein MalGlc (I)-C25H22O13 b | 6.1 | 519.1133 | 519.1179 → 271.0605 | − | + | − |

| 28 | Genistein CouGlcAGlcA (II)-C36H32O19 b | 6.3 | 769.1611 | 769.1589 → 447.0928 → 271.0593 → 323.0769 | + | − | − |

| 29 | Genistein FerGlcAGlcA (III)-C37H34O20 a | 6.3 | 799.1716 | 799.1722 → 447.0920 → 271.0607 → 353.0876 | + | − | − |

| 30 | Formononetin Glc-C22H22O9 a | 6.3 | 431.1337 | 431.1353 → 269.0798 | + | + | − |

| 31 | Biochanin A MalGlc (I)-C25H24O13 a | 6.5 | 533.1290 | 533.1291 → 285.0762 | + | + | + |

| 32 | Genistein FerGlcAGlcA (IV)-C37H34O20 a | 6.4 | 799.1716 | 799.1697 → 447.0929 → 271.0601 → 353.0873 | + | − | − |

| 33 | Afrormosin Glc-C23H24O10 a | 6.5 | 461.1442 | 461.1418 → 299.0905 | + | + | + |

| 34 | Irisolidone MalGlc-C26H26O14 b | 6.6 | 563.1395 | 563.1398 → 315.0852 | + | + | + |

| 35 | Genistein CouGlcAGlcA (III)-C36H32O19 a | 6.7 | 769.1611 | 769.1589 → 447.0922 → 271.0598 → 323.0769 | + | − | − |

| 36 | Biochanin A MalGlc (II)-C25H24O13 b | 6.8 | 533.1290 | 533.1296 → 285.0761 | + | + | + |

| 37 | Genistein FerGlcAGlcA (V)-C37H34O20 a | 6.8 | 799.1716 | 799.1697 → 447.0929 → 271.0601 → 353.0873 | + | − | − |

| 38 | Formononetin MalGlc (I)-C25H24O12 a | 7.1 | 517.1341 | 517.1332 → 269.0804 | + | + | + |

| 39 | Formononetin MalGlc (II)-C25H24O12 a | 7.3 | 517.1341 | 517.1352 → 269.0805 | + | + | + |

| 40 | Afrormosin MalGlc (I)-C26H26O13 a | 7.4 | 547.1446 | 547.1444 → 299.0907 | − | + | − |

| 41 | Afrormosin MalGlc (II)-C26H26O13 a | 7.7 | 547.1446 | 547.1444 → 299.0907 | + | + | + |

| 42 | Medicarpine MalGlc-C25H26O12 b | 8.1 | 519.1497 | 519.1484 → 271.0964 | + | + | + |

| Free aglycones x | |||||||

| 43 | Daidzein-C15H10O4 a, c | 6.6 | 255.0652 | 255.0649 | − | + | + |

| 44 | Genistein-C15H10O5 a, c | 8.4 | 271.0601 | 271.0596 | − | + | + |

| 45 | Biochanin A-C16H12O5 a, c | 8.9 | 285.0757 | 285.0762 | − | + | + |

| 46 | Naringenin-C15H12O5 a, c | 8.9 | 273.0757 | 273.0753 | − | + | + |

| 47 | Liquiritigenin-C15H12O4 b | 9.7 | 257.0808 | 257.0818 | − | + | + |

| 48 | Iirosolidone or dimethoxyluteolin-C17H12O6 b | 9.7 | 315.0863 | 315.0684 | − | + | + |

| 49 | Formononetin-C16H12O4 a, c | 11.0 | 269.0808 | 269.0806 | − | + | + |

| 50 | Chrysoeriol-C16H12O64 a, c | 11.3 | 301.0707 | 301.0717 | − | + | + |

| 51 | Afrormosin-C17H12O5 a | 12.0 | 299.0914 | 299.0902 | − | + | + |

| 52 | Medicarpin-C16H14O4 b | 12.3 | 271.0965 | 271.0956 | − | − | + |

1Substitution pattern on the aglycone of sugar moieties and acyl groups on sugar rings was not solved during LC/MS analyses; abbreviations of sugars and acyl groups: GlcA-glucuronic acid, Glc-glucose, Mal-malonic acid, Fer-ferrulic acid, Cou-Coumaric acid, the most probable substitution of sugars is at 7-O- position of aglycones, for example, 7-O-glucuronopyranosyl-(1-2)-O-glucuronopyranoside or 7-O-glucoside, acylation position of the sugar ring with an aliphatic or aromatic acid is not known

2Exact m/z values of the precursor ([M + H]+) and product ions (among other Y1 + and Y0 + ions)

aStructure of aglycone confirmed in pseudo MS3 experiments

bAglycone defined on basis of elemental composition of the [M + H]+ ion and literature data

cConfirmation with the retention time-of standard

xFree aglycones identified in the extract samples from the tissues and/or culture medium

We observed small differences in the composition of extracts obtained from hairy roots and suspension root cell cultures, and except for qualitative differences (Table 1), there were also observed quantitative differences (Fig. 3). In both types of cultures in samples obtained from cells and media, free aglycones were recognized (Table 1). Composition of the cell extracts of the root suspension culture described in our work was comparable but not identical to the data presented by Farag et al. ( 2007, 2008, 2009). The observed differences may be the result of various conditions, in which the cultures were maintained. The following aglycones of glycoconjugates were recognized in the extracts of roots, suspension cells, and hairy root cultures: daidzein, formononetin, genistein, biochanin A, afrormosin, irisolidone. Additionally, we saw the flavones, luteolin and 4′-methylluteolin (chrysoeriol). These free aglycones were not detected in the root tissue extracts. It should be noted that the free aglycones were more abundant in the media than in the suspension cells and hairy root tissues. It is also worth noting that in our experiments on hairy roots under biotic (cell wall extract from Phoma medicaginis) and abiotic (CuCl2) stress conditions on the cell suspension, the amount of free aglycones found in the media of the treated materials increased substantially. We also noted the presence of medicarpine (data not shown).

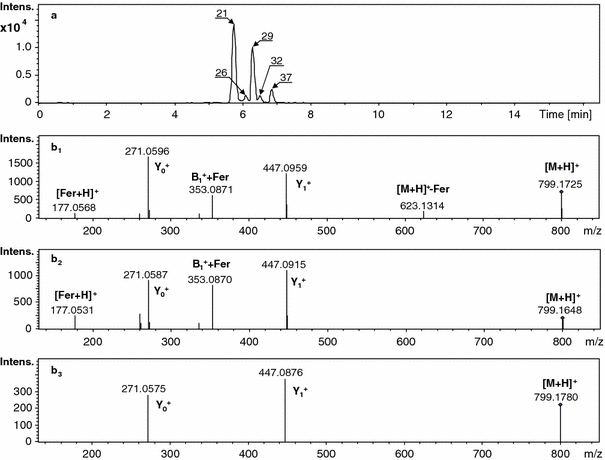

Substantial differences were observed between seedling roots and the cultures derived from root tissues. This was especially exemplified by the composition of flavonoid glycoconjugates and their malonylated derivatives. It is possible that the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway is activated differentially in such materials, depending on the nature of the samples and the condition under which they are grown. Isoflavones were synthesized with higher efficiency in cultures than in root tissue. Glycosylation and further acylation of aglycones were observed in different samples with various sugars, glucuronic acid, and/or glucose. Additionally, the acylation processes of flavonoid glycosides were affected. In seedling roots, we observed acylation of the glucuronides that occurred exclusively with aromatic acids. Flavonoid glycosides substituted with glucose were acylated only with malonic acid. In both types of cultures (hairy root and suspension), the monoglucosides of isoflavones present were acylated with malonic acid. In most cases, malonylation occurred on isoflavone glucosides. The substitution pattern of sugars on the aglycone hydroxyls was impossible to elucidate from the registered mass spectra. In addition, glycosidic bond arrangement was not established. This information would be achievable from NMR data only. However, in the CID MS/MS spectra of the protonated molecules for consecutive isomeric compounds eluted from the LC column, differences in the relative intensities of product ions created after cleavage of the glycosidic bonds in the molecules were observed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Single-ion chromatograms and mass spectra of the protonated molecule [M + H]+ at m/z 799 (registered with an accuracy of ± 0.05 m/z) for genistein feruoyl diglucuronide isomers-21, 26, 29, 32, 37 present in the extracts obtained from M. truncatula root tissue (a); CID MS/MS spectra (MS2) registered for consecutive isomeric compounds-21, 29 and 37 separated on a LC column (b 1, b 2, b 3)

The basic difference between samples obtained from the M. truncatula seedling roots and the suspension root cell culture or hairy roots is that only in the seedling roots were the presence of glucuronides of isoflavones and their derivatives acylated with aromatic acids (ferrulic or coumaric acid) observed. It should be further noted that in roots and leaves, the aglycones substituted with glucuronic acids are different. In the case of roots, there are isoflavones rather than flavones. Qualitative variations between the suspension cell culture and hairy roots are rather small. The number of isoflavone glycoconjugates in the roots is much higher than in the cultures.

The differences observed in the composition of target secondary metabolites suggest that some regulatory processes occurring in particular tissue may affect the final metabolomic picture. This is especially true when the plant material represents different systems, such as suspension cells or hairy root cultures. In the whole plant as well as in plant material obtained from different biotechnological approaches, the biochemical and physiological processes are not exactly comparable. Thus, it is extremely important to adjust the experimental methods and to use great caution when drawing general conclusions about how plant reacts to various stresses.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgment

We are kindly grateful to Jeffrey Kozal for careful reading of the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Boisson-Dernier A, Chabaud M, Garcia F, Bécard G, Rosenberg C, Barker DG. Hairy roots of Medicago truncatula as tools for studying nitrogen-fixing and endomycorrhizal symbioses. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2001;14:693–700. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovy A, Schijlen E, Hall RD. Metabolic engineering of flavonoids in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum): the potential for metabolomics. Metabolomics. 2007;3:399–412. doi: 10.1007/s11306-007-0074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeckling CD, Huhman DV, Farag MA, Smith JT, May GD, Mendes P, Dixon RA, Sumner LW. Metabolic profiling of Medicago truncatula cell cultures reveals the effects of biotic and abiotic elicitors on metabolism. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2005;56:323–336. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farag MA, Deavours BE, de Fatima A, Naoumkina M, Dixon RA, Sumner LW. Integrated metabolite and transcript profiling identify a biosynthetic mechanism for hispidol in Medicago truncatula cell cultures. Plant Physiology. 2009;151:1096–1113. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.141481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farag MA, Huhman DV, Dixon RA, Sumner LW. Metabolomics reveals novel pathways and differential mechanistic and elicitor-specific responses in phenylpropanoid and isoflavonoid biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula cell cultures. Plant Physiology. 2008;146:387–402. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.108431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farag MA, Huhman DV, Lei Z, Sumner LW. Metabolic profiling and systematic identification of flavonoids and isoflavonoids in roots and cell suspension cultures of Medicago truncatula using HPLC–UV–ESI–MS and GC–MS. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossen T, Andersen ØM. Spectroscopic techniques applied to flavonoids. In: Andersen ØM, Markham KR, editors. Flavonoids: chemistry, biochemistry and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 37–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiński M, Kachlicki P, Rodziewicz P, Figlerowicz M, Stobiecki M. Changes in the profile of flavonoid accumulation in Medicago truncatula leaves during infection with the fungal pathogen, Phoma medicaginis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2009;47:847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska I, Stochmal A, Kapusta I, Janda B, Pizza C, Piacente S, Oleszek W. Flavonoids from barrel medic (Medicago truncatula) aerial parts. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55:2645–2652. doi: 10.1021/jf063635b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I, Routaboul JM, Baudry A, Pourcel L, Nesi N, Caboche M. Genetics and biochemistry of seed flavonoids. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2006;57:405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March R, Brodbelt J. Analysis of flavonoids: tandem mass spectrometry, computational methods, and NMR. Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Physics. 2008;43:1581–1617. doi: 10.1002/jms.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczak Ł, Stobiecki M, Jasiński M, Oleszek W, Kachlicki P. Fragmentation pathways of acylated flavonoid diglucuronides from leaves of Medicago truncatula. Phytochemical Analysis. 2010;21:224–233. doi: 10.1002/pca.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth D, Marsden-Edwards E, Kachlicki P, Stobiecki M. Differentiation of isomeric malonylated flavonoid glyconjugates in plant extracts with UPLC-ESI/MS/MS. Phytochemical Analysis. 2008;19:444–452. doi: 10.1002/pca.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naoumkina M, Farag MA, Sumner LW, Tang Y, Liu Ch-J, Dixon RA. Different mechanisms for phytoalexin induction by pathogen and wound signals in Medicago truncatula. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:17909–17915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708697104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes-Lopez O, Cervantes-Ceja ML, Vigna-Perez M, Hernandez-Perez T. Berries: improving human health and healthy aging, and promoting quality life-A Review. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2010;65:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s11130-010-0177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasain JK, Wang C-C, Barnes S. Mass spectrometric methods for the determination of flavonoids in biological samples. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2004;37:1324–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt HJ, Puhler A, Broer I. Transgenic root nodules of Vicia hirsuta: a fast and efficient system for the study of gene expression in indeterminate-type nodules. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions. 1993;6:699–706. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-6-699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schijlen EGW, de Vos CHR, van Tunen AJ, Bovy AG. Modification of flavonoid biosynthesis in crop plants. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:2631–2648. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliemann W, Ammer C, Strack D. Metabolite profiling of mycorrhizal roots of Medicago truncatula. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:112–146. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stobiecki M, Kachlicki P. Isolation and identification of flavonoids. In: Grotewold E, editor. The Science of Flavonoids. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Veitch NC. Isoflavonoids of the Leguminosae. Natural Product Reports. 2009;26:776–802. doi: 10.1039/b616809b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veitch NC, Grayer REJ. Flavonoids and their glycosides, including anthocyanins. Natural Product Reports. 2008;25:555–611. doi: 10.1039/b718040n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Subramanian S, Stacey G, Yu O. Flavones and flavonols play distinct critical roles during nodulation of Medicago truncatula by Sinorhizobium meliloti. Plant Journal. 2009;57(1):171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.