Abstract

Background:

Higher plants are considered as a well-known source of the potent anticancer metabolites with diversity of chemical structures. For instance, taxol is an amazing diterpene alkaloid had been lunched since 1990.

Objective:

To isolate the major compounds from the fruit extract of Cucumis prophetarum, Cucurbitaceae, which are mainly responsible for the bioactivities as anticancer.

Materials and Methods:

Plant material was shady air dried, extracted with equal volume of chloroform/methanol, and fractionated with different adsorbents. The structures of obtained pure compounds were elucidated with different spectroscopic techniques employing 1D (1H and 13C) and 2D (COSY, HMQC and HMBC) NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometry) and ESI-MS (Eelectrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry) spectroscopy. The pure isolates were tested towards human cancer cell lines, mouse embryonic fibroblast (NIH3T3) and virally transformed form (KA3IT).

Results:

Two cucurbitacins derivatives, dihydocucurbitacin B (1) and cucurbitacin B (2), had been obtained. Compounds 1 and 2 showed (showed potent inhibitory activities toward NIH3T3 and KA31T with IC50 0.2, 0.15, 2.5 and 2.0 μg/ml, respectively.

Conclusion:

The naturally cucurbitacin derivatives (dihydocucurbitacin B and cucurbitacin B) showed potent activities towards NIH3T3 and KA31T, could be considered as a lead of discovering a new anticancer natural drug.

Keywords: Cucumis prophetarum, cucurbitacin B, dihydrocucurbitacin B, mouse embryonic fibroblast and virally transformed form

INTRODUCTION

Generally, there are two different approaches used for discovering of antitumor compounds; bio-chemical approach and target-based approach. The first approach has gained a significant attention in the last decades.[1] This resulted in discovery of antitumor agents. For instance, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved imatinib mesilate as a first-line treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia.[2] The use of high-throughput screening is aimed at discovery of anticancer agents employing mouse embryonic fibroblast (NIH3T3) and virally transformed form (KA3IT) cells. The selection of these cells based on that they are adherent, easily manipulated, and well characterized.[3,4]

The Cucurbitaceae are mostly known prostrate or climbing herbaceous annuals plants comprising about 125 genera and 960 species, includes the melons and gourd crops like cucumbers. The family is predominantly distributed around the tropics, where edible fruits are grown. The diversity of the cucurbitacins’ activities, especially cytotoxicity and antifeedants, is a good evidence for further investigations.[5–7] Recently, they were exploited for their antitumor properties, differential cytotoxicity toward renal, brain tumor, and melanoma cell lines,[8] inhibition of cell adhesion,[9] and finally, antifungal effects.[10] A computer survey includes science finder data base, indicated that a number of cucurbitacins were isolated from genus Cucumis. For example, cucurbitacins were isolated from Cucumis prophetarum: cucurbitacin (B, E, I, O, P, and Q1); dihydocucurbitacin (D and E), isocucurbitacin (B, D, and E) and dihydroisocucurbitacin (D and E).[11–15]

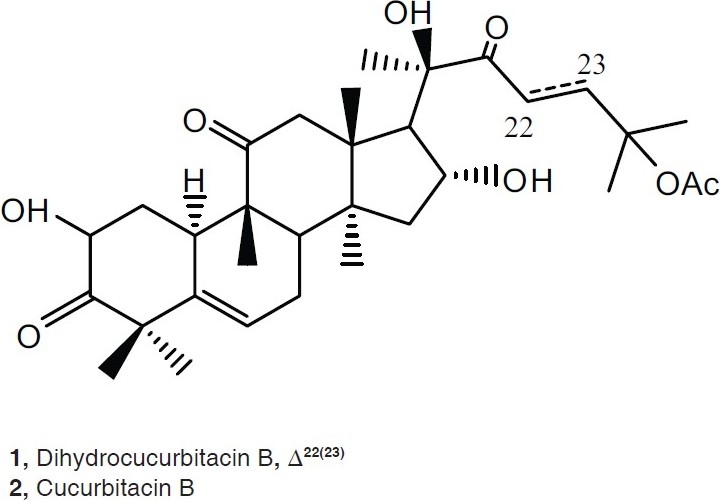

In continuation of our research program which interested in the isolation of the bioactive secondary metabolites from marine macro organisms or higher plants, collected from Saudi Arabia.[16–18] The fruits of Cucumis prophetarum L., belongs to family Cucurbitaceae, wild plant growing in the desert of Makah, 80 km from Jeddah Saudi Arabia. The total extract (Chloroform: Methanol [1: 1]) had been fractionated using different chromatographic techniques, led to purification of two cucurbitacins derivatives; dihydocucurbitacin B (1) and cucurbitacin B (2). The compounds 1 and 2 [Figure 1] showed potent inhibitory activities toward mouse embryonic fi broblast (NIH3T3) and virally transformed form (KA3IT) cells with IC50 0.2, 0.15, 2.5, and 2.0 μg/ml, respectively.

Figure 1.

Structures of dihydocucurbitacin B (1) and cucurbitacin B (2)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General procedure

Chromatographic material: silica gel type 60-120 mesh.was used form Column Chromatography (CC). Silica gel GF 254 was used for Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC). Finally, silica gel 60 F254 was used for Preparative Thin Layer Chromatography (PTLC). Electron impact mass spectra were determined at 70 ev on a Kratos EIMS-25 instrument. All NMR spectra were recorded on (1D and 2D) NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian VI-500 MHz spectrometer. LC-CIMS was performed using an API 2000, LC MS/MS from Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex. Bruker Avance 300 DPX and 500 DRX spectrometers in CDCl3. Chemical shifts are given δ (ppm) relative to TMS as internal standard. The spray reagent used is: Anisaldehyde-sulphuric acid. A freshly prepared solution was made by adding concentrated sulphuric acid (1 ml) to a solution of anisaldehyde (0.5 ml) in acetic acid (50 ml).

Plant material

Cucumis prophetarum L. was collected from wild plants growing from the desert of Makah, Saudi Arabia. The fresh fruits were separated, air-dried, and powdered. A voucher sample was deposited at the Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Extraction and purification

The fruits of C. prophetarum (500 gm) were extracted twice by chloroform: methanol (1:1) at room temperature. The extract was concentrated under reduced pressure and led to yellowish brown residue (25 gm). This material was chromatographed on a column of silica gel. The total extract was fractionated by NP silica (500 gm, 80 cm × 2.5 cm) employing pet. Ether/CHCl3/MeOH (50 ml each fraction). The fractionation was followed by TLC using anisaldehyde-sulphuric acid as spraying reagent. The fraction eluted by chloroform: methanol (9: 1) was collected and purified by Sephadex LH 20 using methanol: chloroform (3:1) followed by preparative TLC silica gel and chloroform: Methanol (9+1), led to 1 (200 mg) and 2 (100 mg)

Cytotoxicity bioassays

Cytotoxic assays[19,20] were performed using two proliferating mouse cell lines, a normal fibroblast line NIH3T3 and a virally transformed form KA3IT. Samples of extract or pure compound (5 mg) were dissolved in 62.2 μl of Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and working solutions made by diluting 20 μl of the DMSO solution into 2 ml of sterile medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO, USA). Two-fold or 2.5-fold dilutions of the extracts of pure compounds from 200 μg/ml to 0.5 μg/ml were prepared in triplicate in the wells of 96-well culture trays (Falcon Micro Test III, # 3072, Becton Dickinson Labware, Lincoln Park, NJ, USA) in 200 μl of medium containing 5% (v/v) calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logon, Utah, USA). Inoculums of 2 \ 103 cells were added to each well in a 100 μl aliquot of 10% calf serum in medium. The 96-well trays of cells were cultured under standard conditions until uninhibited cultures (control) became confluent. The contents of the wells were decanted, and each cell layer washed with a small amount of the medium. The wells were filled with formal saline (3.7% w/v formaldehyde in 0.15 ml NaCl), and allowed to stand at room temperature for at least 30 minutes. The trays was washed with tap water, and attached cells stained by adding two drops of 0.5% (w/v) crystal violet solution in 20% (v/v) aqueous methanol added to each well. The trays was washed with tap water, and the IC50 estimated visually as the approximate concentration that causes 50% reduction in the number of stained cells adhering to the bottom of the wells.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

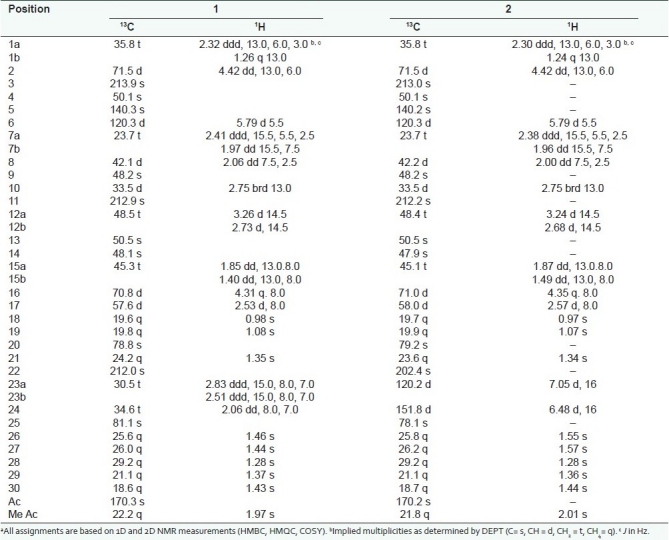

The chromatographic purification of the total extract obtained from fruits of C. prophetarum resulted in the isolation of two compounds belong to cucurbitacins-type triterpens; dihydocucurbitacin B (1) and cucurbitacin B (2). They identified by employing 1D (1 H and 13C) and 2D (COSY, HMQC and HMBC) NMR, and ESI-MS spectroscopy. The pure isolates were tested towards human cancer cell lines, mouse embryonic fibroblast (NIH3T3) and virally transformed form (KA3IT). The compounds 1 and 2 showed cytotoxic activities toward NIH3T3 and KA31T with IC50 0.2, 0.15, 2.5, and 2.0 μg/ml, respectively. The structure elucidation of 1, commenced when the molecular formula of C32H48O8 was established by LC-ESI-MS at 583 [M+ + Na]. This result was validated by HRESIMS, m/z 583.3245 [M+ Na]+. The 13C NMR spectra (1 H decoupled and DEPT) of 1 showed 32 resonances attributable to 9 X CH3, 7 X CH 2, 6 X CH, and 10 X C [Table 1]. Three of the eight elements of unsaturation, as indicated by the molecular formula of 1, deduced to be a carbonyl group appeared at δc 213.9, 212.9, and 212.0, for C-3, C-11, and C-22, respectively, and an olefinic proton at δc 5.79 (J= 5.5) assigned for H-6 of the double bond at Δ(5)6. The molecule, thus, has four rings. As the 1H and 13C NMR data enabled all but three of the hydrogen atoms within 1 to be accounted for, it was evident that the remaining three protons were present as part of a hydroxyl functions. After association of all the protons with directly bonded carbons via 2D NMR (HMQC) spectral measurements, it was possible to deduce the structure of 1 by interpretation of the 1H–1H COSY and 1H–13C HMBC spectra. From the 1H–1H COSY spectrum of 1, a 1H–1H spin system between H-2 and H2-1 and between H2 -1 and H-10 was observed. Long-range C-H correlations observed between the resonances of H-8 and those of, C-6, C-7, C-9, C-10 and C-19; between H 2 -1 and C-2, C-3, C-5, C-8, C-9, and C-19; between H-2 and C-1, C-3, C-4, and C-10; between H-6 and C-4, C-5, C-7, C-8, and C-10; between H3 -29 and C-3, C-4, and C-5 and between H3 -30 and C-3, C-4, and C-5 established ring A and B, which are fused together. HMBC correlations, this time observed between H3 -28 and C-8, C-14, and C-15, as well as correlations between H-16 and C-13, C-14, C-15, and C-17, and also correlations between H 3 -18 and C-12, C-13, C-14, C-17 were observed. Long-range C-H correlations observed between the resonances of H-12 and C-11, C-13, C-17, were observed. Ring C was established by deduction through the previous data. From the 1H–1H COSY spectrum of 1, a 1H–1H spin system between H2 -15 and H-14 and H2 -16 and between H2 -16 and H-17 were observed indicated the C-C bond between C-14 to C-15 and C-15 to C-16 and C-16 to C-17. Ring D was established based on 1H–1H COSY and 1H – 13C HMBC spectra. The main skeleton of 1 was established as steroidal derivative. From 1H–1H COSY, correlations were observed between H2 -23 and H2 -24. Extensive investigation of the HMBC correlation between H3 -21 and C-20 and C-22 (C=O) was observed. Long range correlations between C-22 and H2 -23 and H2 -24 led to establishing the side chain as iso-heptane derivative. This side chain is attached to the steroidal nucleus the connection between C-17 and C-20 based on HMBC correlations, between H3 -21 and C-17 and C-20. The positions of the three hydroxyl groups were assigned by examining the correlation obtained from the 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts and supported by the 1H–1H COSY, 1H –13C HMBC spectral data. The remaining from the structure of 1, is the acetate moiety, which connected to C-25 based on the 13C chemical shift. The spectral data of 1, is well fitted with published data with dihydocucurbitacin B, which was isolated from Bryonia cretica.[15] It is isolated from the first time from C. prophetarum of Saudi source.

Table 1.

1H (CDCl3, 500 MHz) and 13CNMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) spectral data of compound 1 and 2a

The structure of 2 was constructed based on the molecular formula of C32H46O8Na, which abstracted from the ESI-MS m/z 581 [M + +Na] and HRESI MS m/z 581.3114[M+ + Na]. After extensive studying of the 1H and 13C NMR spectral data indicated that the doublet at 4.42 (J =13.0, 6.0) and quartet at 4.35 (J = 8.0) were assigned for H-2 and H-16, respectively. A normal H2 -1 shift at 2.30 (1H, ddd, J = 13.0, 6.0, 3.0 Hz), 1.24 (1H, q, I = 13.0 Hz). An acetate signal was clear from 1H and 13C shifts at 2.08 and 170.2 ppm, respectively. The spectra also exhibited two double bond one at 5.79 (d, J =5.5) and the other at 7.05(1 H, d, J = 16.0 Hz), 6.48 (1 H, d, J = 16.0 Hz), which were assigned for C-6 and C23 =C24, respectively. The structures also have three carbonyl groups by 13C NMR at 213.0, 212.2, and 202.4, for C-3, C-11 and C-22, respectively. The structure also has eight methyls at δ 1.57, 1.55, 1.44, 1.36, 1.34, 1.29, 1.08, and 0.98 ppm. It was clear from the spectral data of 2, that it is cucurbitacin B, which was published before.[11,12]

The potent activities of compounds 1 and 2 toward NIH3T3 and KA31 will open the gate for new era of discovering anticancer drug especially for the steroidal compounds, which lead to discovering of new anticancer natural drugs.

CONCLUSION

This manuscript investigates the fractionation of Cucumis prophetarum, Cucurbitaceae aiming at finding or discovering a bioactive metabolites. This study afforded dihydocucurbitacin B (1) and cucurbitacin B (2) [Figure 1]. The structures of the two compounds were elucidated by spectroscopic analyses including: 1D (1H and 13C) and 2D (COSY, HMQC and HMBC) NMR, and ESI-MS spectroscopy. The cytotoxicity of 1 and 2, towards human cancer cell lines, mouse embryonic fibroblast (NIH3T3) and virally transformed form (KA3IT) cells, has been estimated. The compound 1 and 2 had potent inhibitory activities toward NIH3T3 and KA31T with IC50 0.2 and 0.15, 2.5, and 2.0 μg/ml, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge SABIC, the Saudi Arabian Company for Basic Industries, for the financial support of this work (MS/8/68), through the collaboration with the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdul-Aziz University.

Footnotes

Source of Support: SABIC, the Saudi Arabian Company for Basic Industries, for the financial support of this work (MS/8/68), through the collaboration with the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdul-Aziz University.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yip KW, Mao X, Au PY, Hedley DW, Chow S, Dalili S, et al. Benzethonium chloride: A novel anticancer agent identified by using a cell-based small-molecule screen. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5557–69. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stockwell BR. Chemical genetics: Ligand-based discovery of gene function. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:116–25. doi: 10.1038/35038557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Druker BJ, Lydon NB. Lessons learned from the development of tyrosine kinase inhibitor for chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:3–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI9083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavie D, Glotter E. The cucurbitacins, a group of tetracyclic triterpenes. Fortschr Chem Org Naturst. 1971;29:307–62. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-3259-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halaweish FT. Cucurbitacins in tissue cultures of Bryonia dioica Jacq., PhD thesis. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miro M. Cucurbitacins and their pharmacological effects. Phytother Res. 1995;9:159–68. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuller RW, Cardellina JH, Cragg GM, Body MR. Cucurbitacin: Differential cytotoxicity, dereplication and first isolation from Gonystylus keithii. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:1442–5. doi: 10.1021/np50112a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musza LL, Speight P, Mcelhiney S, Brown CT, Gillum AM, Cooper R, et al. Cucurbitacins: Cell adhesion inhibitor from Conobea scoparioides. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:1498–502. doi: 10.1021/np50113a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bar-nun N, Mayer AM. Cucurbitacins-repressor of induction of laccase formation. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:1369–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Rawi A. Wild plants of Iraq with their distribution. Baghdad: Government Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afifi MS, Ross SA, Elsohly MA, Naeem ZE, Halawelshi FT. Cucurbitacins of Cucumis prophetarum and Cucumis prophetarum. J Chem Ecol. 1999;25:847–59. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atta-Ur-Rahman A, Ahmed VU, Khan MA, Zehra F. Isolation and structure of cucurbitacin Q1. Phytochemistry. 1973;12:2741–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gitter S, Gallily R, Shohat B, Lavie D. Studies on antitumor on the antitumor effects of cucurbitacins. Cancer Res. 1961;21:516–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallily R, Shohat B, Kalish J, Gitter S, Lavie D. Further studies on the antitumor effect of cucurbitacins. Cancer Res. 1962;22:1038–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda H, Nakashima S, Abdel-Halim OB, Morikawa T, Yoshikawa M. Cucurbitane-type triterpenes with anti-proliferative effects on U937 cells from an Egyptian natural medicine, Bryonia cretica: Structures of new triterpene glycosides, bryoniaosides A and B. Chem Pharm Bull. 2010;58:747–51. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alarif WM, Ayyad SE, Al-lihaibi SS. Acyclic Diterpenoid from the Red Alga Gracilaria Foliifera. Rev Latinoam Quím. 2010;38:52–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alarif WM, Abou-Elnaga ZS, Ayyad SE, Al-Lihaibi SS. Insecticidal metabolites from the green alga Caulerpa racemosa. Clean-Soil, Air, Water. 2010;38:548–57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayyad SE, Makki MS, Al-Kayal NS, Basaif SA, El-Foty KO, Asiri AM, et al. Cytotoxic and Protective DNA damage of three new Diterpenoids from the brown alga Dictoyota dichotoma. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbas HK, Mirocha CJ, Shier WT, Gunther R. Procedures for bioassay, extraction and purification of wortmannin, the hemorrhagic factor produced by Fusarium oxysporum N17B grown on rice. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1992;75:474. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shier WT. An undergraduate experiment to demonstrate the use of cytotoxic drugs in cancer chemotherapy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1983;47:216. [Google Scholar]