Abstract

Imaging techniques play an important role in evaluating the complex anatomy of bone and soft tissues of the wrist. The standard wrist radiographs and specialized views still form a very important imaging modality to unravel the wrist pathology in their simplest forms. This article discusses the routine radiography of the wrist followed by ancillary views and dynamic studies for each of the routine view described that helps reveal both static and dynamic pathologies. The literature search was carried out using the search strings or key words, and the databases were searched using the time frame of 1990 to 2011 that included Scopus, MD consult, Web of Knowledge, Pub Med, Ovid Medline and Cochrane Library. The print journals and books available at Manipal University library were hand searched and secondary search was done for the relevant articles included in the references of primary articles. Full articles as well as abstracts were used for the review.

Keywords: Imaging, plain radiography, wrist

INTRODUCTION

When Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen created the radiograph of his wife Anna Bertha's hand in December 1895, the history of radiography and that of the hand and wrist imaging took its birth.[1] Its first clinical application was also to detect a pathology of the wrist, that is, Colles’ fracture a year later.[2] From a 20-min exposure needed at that time for a radiograph to milliseconds exposure now, and from a plain radiograph to advanced imaging techniques available today, the understanding of hand and wrist imaging has leaped many folds.

Despite these advancements, the humble radiograph still remains the single most important imaging modality for hand and wrist.[3,4] This conventional technique produces a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional anatomical data on a photographic film but, using two views projected perpendicular to one another, three-dimensional perspective can be achieved.[4,5]

Standard projections for the wrist are Postero anterior and lateral views. Some authors also consider oblique view as part of the standard views.[6] The following section of this article describes the standard radiographic views first and proceeds to describe any ancillary views of the same and finally dynamic studies using these projections.

The compartmentalization and intricate anatomy of structures in the wrist makes interpretation of wrist pathology a daunting task at times. Hence, an appropriate combination of these views will help the clinician to better analyse the underlying pathology in the preliminary stages of investigations using these conventional radiographs, which should always be preceded by accurate clinical examination. Advanced imaging techniques later become more focused and useful if the initial interpretation of conventional imaging was methodical.

The literature search was carried out using the following search strings or key words: radiography, plain film, roentgenography, wrist, imaging techniques and wrist pain. To identify published research, the following databases were searched using the time frame of 1990 to 2011. The databases included Scopus, MD consult, Web of Knowledge, Pub Med, Ovid Medline and Cochrane Library.

The print journals and books available at Manipal University library were hand searched and secondary search was done for the relevant articles included in the references of primary articles. Full articles as well as abstracts were used for review.

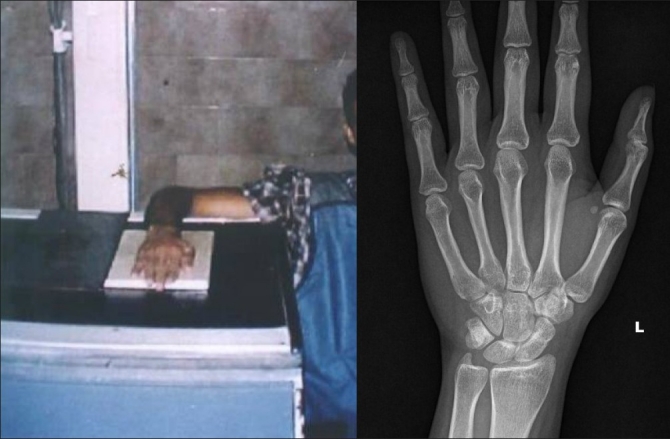

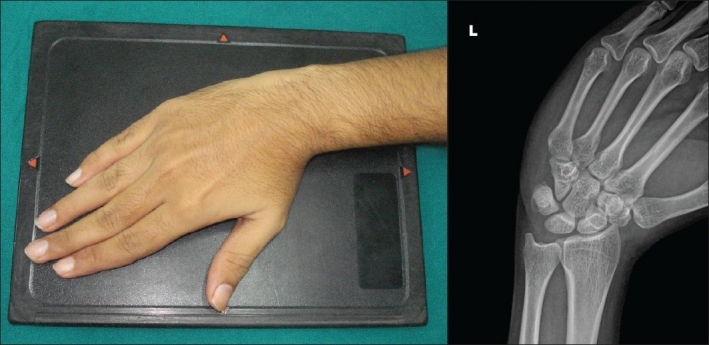

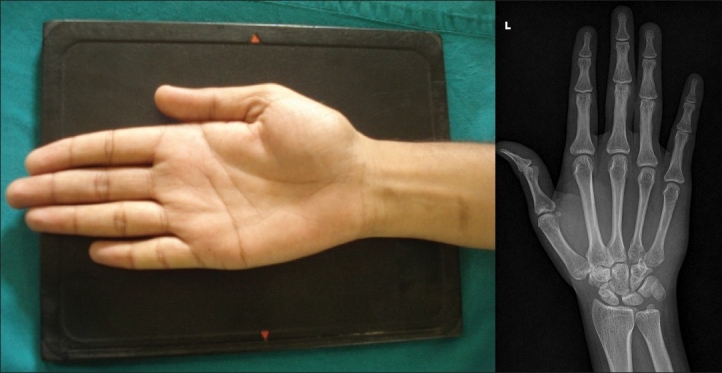

POSTEROANTERIOR VIEW

The posteroanterior (PA) projection is obtained with the shoulder abducted 90° from the trunk and the elbow flexed at 90° with the ulna perpendicular to the humerus and forearm in pronated position [Figure 1]. The wrist should be in neutral position with no flexion, extension or deviation. The hand should be palm down on the cassette with fingers extended.[1] This position ensures that there is no rotation between the radius and the ulna and permits a standard method of visualizing intercarpal relationships and bone length.[7]

Figure 1.

Postero anterior view. The central beam is aligned vertical over radial styloid 100 cm from the film

In this view, the ulnar styloid is seen arising from the ulnar-most border of the ulna. With the wrist in the neutral position, one-half or more of the lunate should contact the distal radial articular surface.[8]

The following features are also noted in the PA view.

The articular surfaces of the carpal bones should be parallel and the joint spaces should be about 2 mm wide. Any change in joint space or the shape of a carpal bone may indicate subluxation or dislocation.[9–12]

Three smooth carpal arcs are formed on the neutral PA view along the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints. Arc 1 follows the proximal surfaces of the scaphoid, lunate and triquetrum. Arc 2 is along the distal surfaces of these same carpal bones, and Arc 3 follows the curvature of the proximal surfaces of the Capitate and Hamate.[13]

These curvilinear arcs are roughly parallel in the normal neutral PA view and disruption of these arcs or abnormal overlapping of adjacent bones on the PA view commonly indicates carpal subluxation or dislocation.

The trapezium, trapezoid and pisiform are overlapping structures on PA view and, hence, arcs do not apply to these structures.[11,12]

The CMC joints should be profiled well and without foreshortening indicating that the fingers were extended and there was no wrist extension.

The long axes of third metacarpal, capitate and the radius should fall in a straight line indicating the wrist was in a neutral position. In most cases the axes are within 10° of this line.[1]

The ECU groove appears as faint longitudinal line extending proximally from the base of ulnar styloid and should be located radial to the fovea.

Ulnar variance depends on the elbow position during radiography that should be at the shoulder height. If the elbow was kept lower than the shoulder height, the ECU groove overlaps the ulnar styloid. More adduction of elbow towards the patient's side will make the ulna become more positive. Hence, ulnar variance measurements should be done only when the ECU groove is in its proper place.[14]

Scaphoid fat stripe: this fat plane lies between the radial collateral ligament and tendon sheath of APL and EPB. Displacement or the absence of this fat stripe in seen in 87% of scaphoid fractures.[15]

Ancillary PA views

Radiocarpal joint view

This is obtained by angulating the beam by 25° to 30° towards the elbow centred just distal to Lister's tubercle for better visualization of radiocarpal articulation [Figure 2]. This view will elongate the scaphoid and shorten the capitate and demonstrate minimum bony overlap with parallelism at the radiocarpal joint and provide more details of scaphoid abnormalities.[14]

Figure 2.

Radiocarpal joint view. The central beam is angled 25° to 30° towards elbow, centred just distal to Lister's tubercle

Dorsal tilt view

It is a PA projection with the central beam angled 25° to 30° towards the fingers, centred on Capitate [Figure 3]. This is useful when there is a suspicion of capitate waist fracture, as here, the capitate is elongated and scaphoid is foreshortened.[14]

Figure 3.

Dorsal tilt view. The central beam is angled 25° to 30° towards fingers, centred on the capitate

Dynamic PA views

Radiographs obtained with radial and ulnar deviation of the wrist are useful for visualizing the carpal bones, particularly the scaphoid, and for assessing carpal mobility and instability. The distances between the carpal bones are normally equal throughout and are unchanged by radial or ulnar deviation.[16]

PA in ulnar deviation

As the wrist is placed in ulnar deviation, the scaphoid rotates its distal pole dorsally and ulnarly and appears elongated. This elongated position of scaphoid allows for easier detection of scaphoid fractures.[8] The scaphoid can also be brought out to length much more by extending the wrist by 20° or by angling the beam towards the wrist by 20° [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

PA ulnar deviation. The central beam is angled 20° longitudinal with the forearm, centred at the midcarpal region

PA in radial deviation

Palmar flexion of the proximal carpal row occurs and the distal pole of the scaphoid rotates into the palm as the wrist is radially deviated. This causes the normal scaphoid to appear foreshortened and exhibit a ring-like appearance of its distal pole as the distal aspect of the scaphoid is seen end on. However, if the same ‘cortical ring sign’ is seen on a PA view in neutral rotation, it may indicate scapholunate dissociation [Figure 5].[16]

Figure 5.

PA radial deviation. The central beam is angled 20° longitudinal with the forearm, centred at the midcarpal region

This view is basically used to visualize the ulnar sided carpal interspaces. If the same view is taken with wrist and hand resting on ulnar surface by tilting 30° oblique and wrist in maximum radial deviation, it becomes a PA radial flexion oblique view. This is an additional view for occult scaphoid fractures.[17]

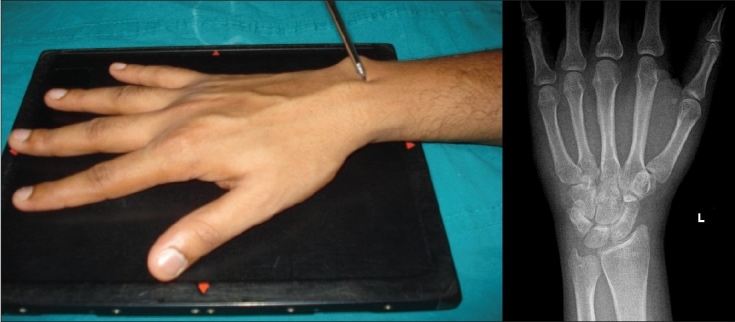

LATERAL VIEW

The lateral view [Figure 6] is critical in assessing intercarpal ligament instability and is obtained with elbow flexed to 90° and adducted against the trunk.[18] The forearm should be midprone and wrist should be in the neutral position such that, in the resulting radiograph, a straight line can be drawn through the axes of radius, lunate, capitate and third metacarpal or they should be coaxial within 10°.

Figure 6.

Lateral view. The central beam is aligned vertical over radial styloid 100 cm from the film

However, the range of capitolunate angle is given to be 0° to 30°.[8]

The following features are to be noted in this view.

The position of scaphoid, pisiform, capitate tells whether there was any wrist pronation or supination.[1] The ‘line of sight’ in this view is when the palmar margin of the pisiform is projected midway between the palmar margins of the distal pole of the scaphoid and the capitate head. This is called as SPC lateral.[19] More the supination of wrist, more the pisiform projects palmar to the scaphoid. The lunate also falsely appears abnormally tilted dorsally.

Given the wide range of curvature of distal ulna in normal wrists, evaluation of the position of ulna with respect to the dorsal surface of distal radius is not an adequate standard to determine if the lateral projection is correctly positioned.[20] Thus, the interpretation of distal radioulnar joint subluxation or dislocation depends on obtaining a completely neutral rotation lateral radiograph. This can only be determined by the relative position of pisiform with the distal scaphoid pole and that of ulna with radius which are normally superimposed well on each other, respectively. With slight pronation the pisiform and ulnar head rotate more dorsally and with slight supination, they project more volar.[21]

The Pronator fat stripe can be identified along the volar aspect of distal radius. Subtle fractures can cause displacement or obliteration of the fat plane.[9,10]

Ancillary lateral views

Carpal boss view or off-lateral view [Figure 7]: this lateral view is taken with the ulnar side of the wrist resting on the cassette, in minimal ulnar deviation and 30° supination. The central beam passes tangent to the dorsal prominence.

Figure 7.

Carpal boss view. The central beam passes through or tangent to the dorsal prominence

This view shows the dorsal carpal boss on a tangent and enables distinction of (1) a separate os styloideum; (2) a bony prominence attached to the second or third metacarpal base or apposing surface of the trapezoid or capitate bones; (3) degenerative osteophytes; and (4) a fracture of the dorsal prominence of the second or third metacarpal.[14]

Lateral scaphoid view [Figure 8]: this is same as the standard lateral view except that the wrist is kept in 30° extension and the beam is centred on the waist of the scaphoid.[18]

Figure 8.

Lateral scaphoid view. The central beam is directed perpendicular to the film and centred on the waist of the scaphoid

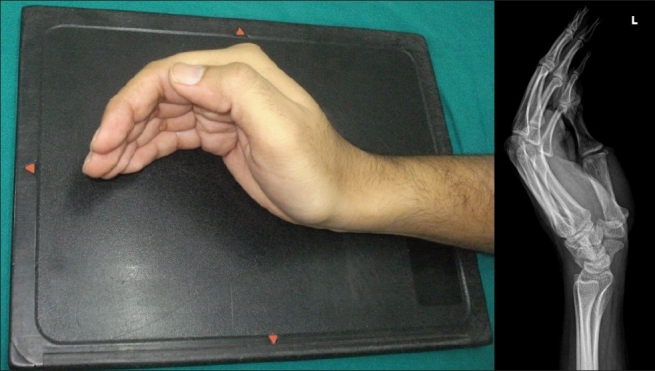

Dynamic lateral views

Lateral flexion and extension views [Figures 9, 10]: for these views, the central beam is directed perpendicular to the film and centred on the waist of the scaphoid. The wrist should be in the true lateral position on both radiographs. The extension and flexion of the wrist is recognized by observation of the long axis of the third metacarpal extended dorsally and flexed volarly, respectively, relative to the long axis of the radius and ulna.[17]

These views demonstrate extension and flexion at the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints in normal wrists and can be further used in evaluation of carpal instability patterns. In particular, these views can assist in distinguishing between a true instability pattern versus normal variance.[14]

Figure 9.

Lateral extension view. The central beam is directed perpendicular to the film and centred to the waist of the scaphoid

Figure 10.

Lateral flexion view. The central beam is directed perpendicular to the film and centred to the waist of the scaphoid

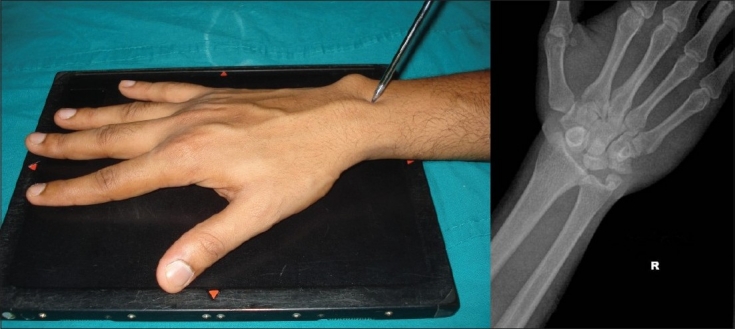

OBLIQUE VIEW

The oblique views [Figure 11] uniquely reveal abnormalities and changes interpretation by increasing the confidence of the final radiographic diagnosis.[6] This view is classically obtained by pronating the wrist by 45° from the lateral position and can be made easy for the patient by using a step wedge to steady the wrist and hand.

Figure 11.

Oblique view

The oblique view is particularly useful in evaluating the radial corner of the wrist including the base of the thumb and the scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal joint. It also provides an additional view for scaphoid tuberosity and waist when ulnar deviation is added to same view. It also shows dorsal triquetral margin fractures.[14]

Ancillary oblique views

Semisupination oblique view: (pisiform, pisotriquetral view) [Figure 12]: the pisiform, palmar aspect of triquetrum, palmar ulnar surface of the hamate and pisotriquetral joint are better visualized by this view which is taken by seating the patient as in for lateral view. The wrist is supinating until it forms an angle of 45° from the true lateral position. The synonymous names for this view include the Norgaard view, the Ball catcher's view or ‘You are in good hands with Allstate’ view. The Norgaard view is optimal for evaluating early erosive changes in hands and wrist of patients with inflammatory arthritis.[8,16,22]

Semi oblique lateral view (radial deviated, thumb abducted lateral view): here the patient's wrist is in maximal radial deviation and thumb in maximum abduction. The forearm is kept 45° supination [Figure 13]. This view reveals a fracture of hook of Hamate.[18]

Figure 12.

Semisupination oblique view. The central beam is directed at the dorsal surface of the carpus

Figure 13.

Semioblique lateral view. The central beam is centred on the web space between the thumb and the index finger

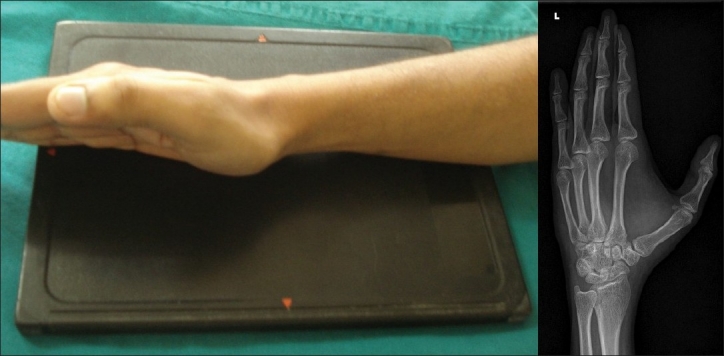

ANTERO POSTERIOR VIEW

The antero posterior or AP view or supinated view [Figure 14] has its specific applications in evaluating wrist pathology. It profiles the scapholunate and lunotriquetral carpal interspaces best and hence used to evaluating them.[1,17] It is also used when the patient cannot pronate and fingers cannot be fully extended.[18]

Figure 14.

Antero posterior view

The dorsum of wrist and hand are flat against the film and beam is centred over the capitate head. In the AP view, the ulnar styloid projects from the centre of ulnar head in contrast with PA view where it is at the ulnar border.[5,23]

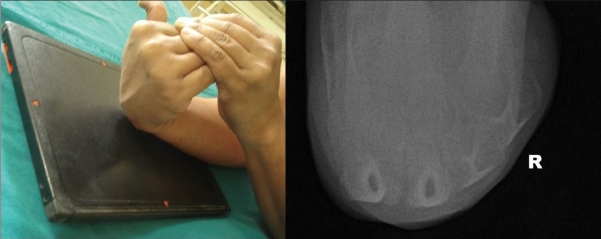

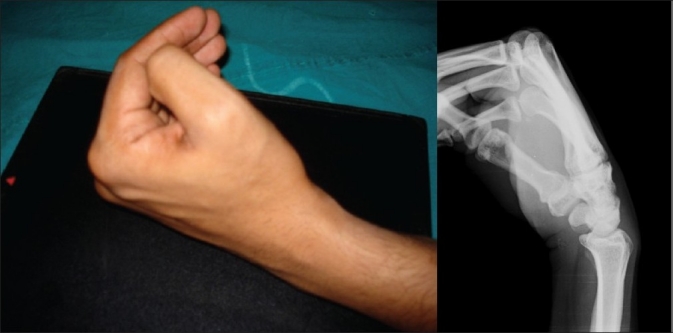

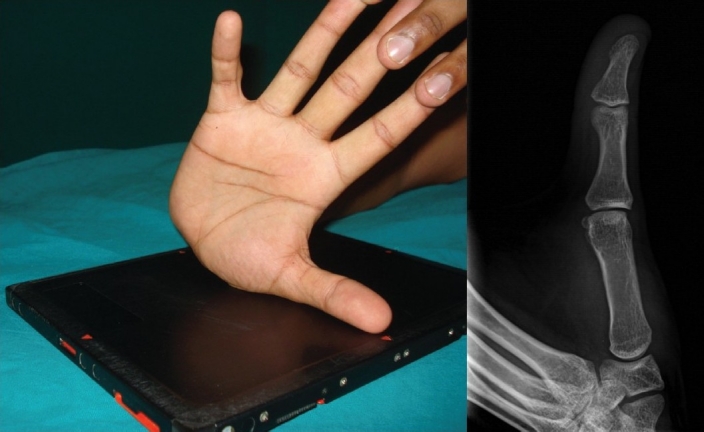

Dynamic AP view (clenched fist view)

The AP view can be used dynamically [Figure 15] by asking the patient to clench his fist actively when the film is taken. This will demonstrate any Scapholunate diastasis effectively. The clenched fist creates enough forces of the contracting muscles to drive the capitate towards the scapholunate joint and bring out the diastasis in a dynamic mode.[1]

Figure 15.

Antero posterior clenched fist view. The central beam is directed perpendicularly at the level of the midcarpal region

The following points are to be kept in mind before making the diagnosis of scapholunate instability on clenched fist view (carpal compression or power grip view).

The clinical correlation of pain and tenderness at the scapholunate joint should guide the radiographic evidence as even wrists with lax ligaments can show the widening on routine radiographs.

It is prudent to obtain the contralateral radiograph of the asymptomatic side as sometimes the scapholunate joint is so well profiled on AP view than other joints so as to give an impression of diastasis.[1]

Compare the width of adjacent capitolunate joint to provide a reference.[1]

The third CMC joint should also be looked at to see its profiling. If it is not profiled then the wrist was in extension or flexion and scapholunate width measurement is not accurate. This is because the scapholunate joint is wider at dorsal and palmar portions than the central portion.[1]

Lastly, both AP and PA clenched fist views are to be taken when suspecting scapholunate instability strongly as sometimes the PA view might show the pathology rather than the AP view.[14]

Ancillary AP view

First carpometacarpal joint view: [Figure 16] this view is taken with the thumb placed in horizontal position and hand hyper extended. The beam is angled 45° towards the elbow. This is a dedicated anteroposterior projection with beam angulation for changes in first CMC joint in arthritis or traumatic conditions like Bennett's fracture.[5]

Figure 16.

First carpometacarpal joint view

OTHER VIEWS

Carpal tunnel view: [Figure 17] this view is obtained with the wrist dorsiflexed and either the ventral aspect of the wrist (Gaynor - Hart method) or the palm placed on the film cassette and the hand hyperextended by grasping the fingers with other hand by the patient.

Figure 17.

Carpal tunnel view

The beam is angled to profile the carpal tunnel by directing it along the volar aspect to a point 2.5 cm distal to base of fourth metacarpal at an angle of 25° to 30° to the long axis.[16]

This view shows the palmar soft tissues and the palmar aspects of the trapezium, scaphoid tuberosity, capitate, hook of the hamate, triquetrum and the entire pisiform.[5,14]

Carpal bridge view: [Figure 18] this view is obtained by placing the dorsum of the wrist on the film and palmar flexing the wrist by 90° approximately. The beam is angulated by 45° in a superoinferior direction towards the wrist. On a properly taken view there is tangential view of the dorsal aspect of the scaphoid, lunate and triquetrum. The superimposed capitate should be visible.[14]

Figure 18.

Carpal bridge view. The central beam is directed to a point 1.5 in proximal to the wrist joint at a superoinferior angle

This view helps in evaluating dorsal surface fractures of the scaphoid and dorsal fractures of other carpal bones, lunate dislocation and also demonstrates calcifications and foreign bodies in the dorsal soft tissues.[16]

SUMMARY

The radiographic projections described earlier require careful attention to positioning, radiographic exposure and collimation of the beam to provide accurate information. A film that is too widely or narrowly collimated, under or over exposed, or inadequately positioned may be misleading.[24] Using a single film to evaluate adjacent anatomical regions like hand and wrist or digits is a false sense of economy because a dedicated set of images of the region of interest is more diagnostic.[1]

Of late, the complex interactions of the carpal bones and the intricate carpal ligamentous network have been better explored by new imaging techniques.[21] Apart from the conventional radiography, the static pathologies are better delineated now with digitally acquired radiography that is superior in image quality. The digital data can also be manipulated to alter the character of the image and can be stored on magnetic media instead of a photographic film. The digital radiographs also depict the soft tissues in a greater detail.[25]

Advanced imaging and identification of dynamic pathological conditions of the wrist are increasingly being done now with fluoroscopy, ultrasonography, scintigraphy, conventional and computed tomography, arthrography and magnetic resonance imaging.[21]

However, it cannot be over emphasized that to use these tools effectively, a close co-operation between the clinician and the radiologist is essential which will result in tailoring an appropriate imaging protocol best suited for the patient.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schreibman KL, Freeland A, Gilula LA, Yin Y. Imaging of the Hand and Wrist. OrthopClinNorth Am. 1997;28:537–82. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg RL. Radiology: An illustrated History. St Louis: Mosby Yearbook; 1992. Early Radiology; p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Distouet JM, Gilula LA, Reinus WR. Roentgenographic diagnosis of wrist pain and instability. In: Lichtman D M, editor. The Wrist and its disorders. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders; 1988. pp. 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taleisnik J. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 1985. The Wrist; pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartoris DJ, Resnick D. Plain Film Radiography: Routine and specialized technique and projections. In: Resnick D, Nijwayama G, editors. Diagnosis of Bone and Joint Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders; 1988. pp. 2–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeSmet AA, Doherty MP, Hollister MC, Smith DL. Are oblique views needed for trauma radiography of the distal extremities? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1561–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.6.10350289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis CM, Yang Z, Gilula LA. Validation of the extensor carpi ulnaris groove as a predictor for the recognition of standard postero-anterior radiographs of the wrist. J Hand Surg. 2002;27A:252–7. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.31150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weisman BN, Sledge CB. Philadelphia PA: Saunders; 1986. Orthopaedic Radiology; pp. 111–67. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berquist TH. New York: Raven Press; 1992. Imaging of Orthopedic Trauma. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernau A, Berquist TH. Baltimore: Urban and Schwarzenberg; 1983. Orthopaedic positioning in Diagnostic Radiology. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilula LA. Carpal injuries: Analytical approach and case exercises. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:513–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.133.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilula LA, Destouet JM, Weeks PM. Roentgen diagnosis of the painful wrist. Clinic Orthop. 1984;187:51–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann FA, Gilula LA. Post-traumatic wrist pain and instability: A radiographic approach to diagnosis. In: Lichtman DM, Alexander AH, editors. The wrist and its disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders; 1997. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin Y, Mann FA, Gilula LA. Positions and techniques. In: Gilula LA, Yin Y, editors. Imaging of the wrist and hand. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1996. p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terry DW, Ramen JE. The navicular fat strip: A useful roentgen feature for evaluating wrist trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1975:124–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.124.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loredo RA, Sorge DG, Garcia G. Radiographic Evaluation of the wrist: A vanishing art. SeminRoentgenol. 2005;40:248–89. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine SM, Lambiase RE. Ancillary radiographic projections of the hand and wrist. JAmSocSurgHand. 2002;2:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert TJ. Imaging of acute injuries to the wrist and hand. RadiolClini North Am. 1997;35:701–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z, Mann FA, Gilula LA, Haerr C, Larsen CF. Scaphopisocapitate alignment: A new criterion to establish a neutral lateral view of the wrist. Radiology. 1997;205:865–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.3.9393549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haerr C, Mann FA, Gilula LA. Presented at the Radiologists society of North America. Chicago: 1993. Selection of landmarks for verifying true frontal and lateral positions (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levinsohn EM. Imaging of the wrist. RadiolClin North Am. 1990;28:905–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brower AC, Flemming DJ. Arthritis in Black and White. 2nd ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders; 1997. Imaging technique and modalities. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kindynis P, Resnick D, Kang HS. Demonstration of the scapholunate space with radiography. Radiology. 1990;175:278–80. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.1.2315496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson AJ, Mann FA, Gilula LA. Imaging of the hand and wrist. J Hand Surg (Br) 1990;15(B):153–67. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_90_90119-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindequist S, Marelli C. Modern Imaging of the Hand, wrist and forearm. J Hand Ther. 2007;20:119–37. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]