Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Obturator hernias (OH) account for a rare presentation to the surgical unit usually associated with bowel obstruction and strangulation. The treatment of this condition is classical laparotomy with repair of the hernia and bowel resection, if deemed necessary; recently, the laparoscopic approach has been reported in literature. This review examines the existing evidence of the safety and effectiveness of the laparoscopic approach for the management of OH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We have conducted a systematic review of the cases reported in the literature between 1991 and 2009, using Medline with PubMed as the search engine, as well as Ovid, Embase, Cochrane Collaboration and Google Scholar databases to identify articles in English language reporting on laparoscopic management for the treatment of this condition.

RESULTS:

A total of 17 articles reporting on 28 cases were found. We describe the pooled data for demographics, operative time, hospital stay, morbidities and method of repair. We also compare to the results of the laparoscopic repair of other types of hernias in the literature.

CONCLUSION:

This approach was found to be a safe and effective approach for the repair of OH as compared to the classical open approach; however, its adoption as the gold standard needs further multicenter trials.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, obturator hernia, review

INTRODUCTION

Obturator hernias (OH) account for a rare presentation to the surgeon and their incidence is 0.073%, usually diagnosed as a cause of bowel obstruction or perforation.[1] Their diagnosis is usually a challenge in both acute and elective settings. The incidence is higher in females with a ratio of 6 : 1, usually in the elderly group of age higher than 70 years; henceforth, the nickname ‘tiny old lady hernia’. Usually, there is no preoperative diagnosis and the hernia can be identified at the time of the operation (usually a laparotomy), reduced, defect repaired directly or with mesh and the bowel assessed for resection or not.[2] This carries the morbidity and mortality associated with a laparotomy for bowel obstruction. Recently, there have been a few case reports in literature advocating the use of laparoscopy of the above treatment of the OH, with the first report coming from Germany.[3] This modality can be used especially for non-acute presentations with the benefits of laparoscopic surgery, especially in decrease of hospital stay and faster return to normal activities.

We have searched the literature for these case reports as a systematic review and we pooled the data to assess the safety and feasibility of the laparoscopic approach to treat this rare condition in both acute and elective settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic literature review was done using PubMed, Ovid, Google Scholar, Embase and Cochrane collaboration using the words obturator hernia and laparoscopic as mesh words with restrictions on the year of publication after 1991 to December 2009. The ‘related articles’ function was used in PubMed to broaden the search, and all titles, abstracts, studies and citations scanned were reviewed. Then, the references of the articles found were also searched manually. Sixty eight articles in total were found.

The inclusion criteria were all published articles reporting on the results of laparoscopic management of OH, even if it is a part of an open series. No restrictions on type of study were made. The manuscript should report on a case or case series of patients who had presented with acute or chronic, strangulated, incarcerated or irreducible OH, or asymptomatic OH that were managed on an elective or emergency setting using a laparoscopic approach. Manuscripts reporting on the open approach, paediatric hernias and laparoscopic approach for other types of hernias were excluded. From the 68 articles, only 17 articles fit our criteria, reporting on 28 laparoscopic cases of OH repair.[4–20]

RESULTS

The pooled data were that of 28 patients. The elective presentation was 20 out of 28 (71%). The female to male ratio was 5.3 : 1. The weighted average age was 53.2 years and when available in the text, the weighted average weight was 55.3 kg with a range of 32 to 82 kg. The weighted average operative time when available in text was 50.6 minutes. Ileus ranged from 2 hours to 4 days after the operation, excluding the operations that necessitated bowel resection. Hospital stay had a weighted average of 1.44 days when the length of stay was mentioned in text. In all the series, there is one report of a complication (3.5%) which was a wound infection after a laparoscopic-assisted bowel resection of non-viable bowel that was complicated by a wound infection treated conservatively by dressing changes for 29 days.[14] There were two conversions (7.0%) for bowel resections in the series after laparoscopic assistance that diagnosed ischemic bowel.

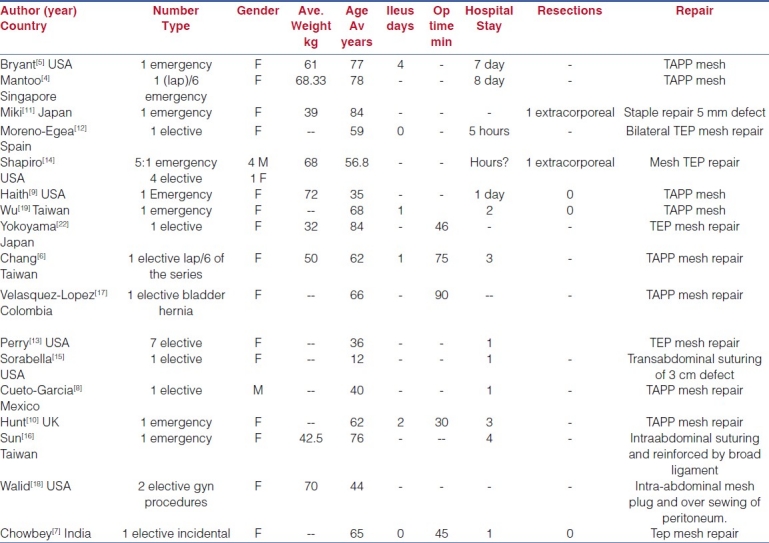

There were eight transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) mesh repairs, 15 totally extraperitoneal (TEP) mesh repairs, four direct repairs by stapling or suturing and one intraperitoneal plug repair. Table 1 summarises all the above results.

Table 1.

Summary of the pooled cases

DISCUSSION

OH are not a common presentation. However, with the advent of computed tomography (CT) technology, this condition is being diagnosed more frequently, especially in the younger population.[21] The acute presentation is that of intestinal obstruction or bowel ischemia and perforation, which is associated with the highest morbidity rate amongst all abdominal wall hernias ranging between 13 and 40%.[4] On the other hand, its elective presentation is that of a reducible lump in the medial upper thigh (or during pelvic or rectal examination) associated with the presence of the Howship-Romberg sign, where the patient complains of medial thigh and hip pain, exacerbated by the adduction and medial rotation of the thigh and relieved by the flexion. This is found in 15 to 50% of presentations and should raise the physicians’ index of suspicion.[23]

The classic surgical approach remains open surgery in order to reduce the hernia, fix the defect and resect any bowel that is deemed non-viable. There is a high incidence of necrotic bowel with this kind of hernia because of the presence of small defects which often lead to strangulation.[2]

With the advent of laparoscopy and the evolution of surgical techniques, there have been reports and case series of strangulated inguinal and spigelian hernias treated with the laparoscopic approach with safe and feasible results.[24] However, the laparoscopic approach to this condition is not widely accepted due to the acute presentation along with the usually significant comorbidities of this group of patients. Nonetheless, in recent literature, there have been some sporadic reports of this approach for OH. We have performed a systematic review of these reports to assess the feasibility of this approach, along with its safety in treating this condition.

The incidence of this presentation, as the literature reports, is higher in females than in males with a ratio of 6 : 1; similarly, this review points out to a ratio of 5.3 : 1. This can be explained by the larger pelvis in females, henceforth more space for the foramina to form defects.[21] The age of the presentation is reported in the literature as average of 70 years; however, this review reports an average of 53.2 years and this may be explained by the pooling of emergency presentations with elective ones, which are more frequently diagnosed these days with the advent of CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning of the pelvis for non-specific neuralgias of the lower extremities in younger patients.[13]

Patients are well known to be of low weight which adds to the possibility of the defects appearing in the pelvis, since emaciated patients lose their pelvic muscle mass allowing for defects to occur. This review has an average weight of patient at presentation of 55.3 kg with an extreme range of 32 to 82 kg. This might also be explained by the above cause of the recent use of CT scanning in elective presentations of healthy and overweight patients.

We can notice from the above results that the majority of the cases (71%) treated successfully with the laparoscopic approach were elective cases diagnosed preoperatively by CT scanning[6,10,16] or an incidental finding during laparoscopy for other conditions or hernias.[7,9,18] This is expected since the technique follows the same principles as for an inguinal hernia repair with a mesh. The minority emergency cases (29%) were treated laparoscopically by reducing the segment of bowel using gentle traction on the efferent limb of the bowel coming out of the defect and then a traditional TAPP approach as per repairing an inguinal hernia. In this acute presentation, the TAPP approach is a must to assess the bowel segment viability after the repair. If TEP was used for acute presentations, then the bowel cannot be assessed, since there is no direct visualisation of the bowel segment in TEP approach but only a visualisation of the sac as it reduces from the defect back into the abdomen.

There were six reports out of eight warranting TAPP for emergency presentations in this review; all the TEP repairs were those of elective cases. If the segment was non-viable, then a laparoscopic-assisted resection and anastomosis is done extracorporeally.[11,14] This is probably better to decrease contamination in the abdominal cavity and reduce the chances of mesh infection. As for the complications, there is a wound infection associated with bowel resection from the umbilical camera port wound and that has been treated conservatively with no report of concomitant mesh infection in that case.[14] Although Shapiro et al. reported 29 days of treatment for that infection, still it is a superficial infection and more likely to occur with bowel resection than with cases with no resection performed.[14]

There are too many techniques described in the literature for the repair of this type of hernia and these include fascial and muscular flaps, peritoneal covering, omental fat plugs, ovary, uterus and round ligament coverage and most recently prosthetic material.[25] When using a laparoscopic approach, most surgeons find it easier to use a mesh as per repairing inguinal hernias laparoscopically. This review supports this as there has been 25 repairs out of the 28 using mesh TAPP, TEPP or even plug; and three repairs primarily with staple or intra-abdominal suturing. There is no adequate data or long follow-up to see the effect of each modality on recurrence rates. All the above claim no recurrences in their patients after a median follow-up of one year.

The present authors’ group had conducted a similar study on the feasibility of the laparoscopic approach for strangulated inguinal hernias; we can compare the results with those findings.[24] This review points out that the average operating time for using the laparoscopic approach for the strangulated/incarcerated OH is less than that for inguinal hernias (50.6 vs 61.3 minutes). The conversion rate is 7% in OH repair as compared to 1.8% in the repair of strangulated inguinal hernias laparoscopically; this might be explained by the fact that OH are of narrower defect size and are more prone for strangulation, and hence the need for a conversion for bowel resection and anastomosis.[24] Hospital stay is less with OH (1.44 days) as compared to inguinal hernia repair (3.8 days), when comparing the laparoscopic approach.[24] Complication rate is also better in OH repair than with the use of this approach for strangulated inguinal hernia repair (3.5% vs 10.4%).[24]

CONCLUSION

The above systematic review demonstrates the feasibility of the laparoscopic repair for OH with reasonable and safe results. The use of this technique is best judged by the operating surgeon and the condition of the patient at the time of the operation. It also depends on the surgeon's expertise in the use of laparoscopy to handle dilated bowel without causing any iatrogenic injury.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bjork KJ, Mucha P, Jr, Cahill DR. Obturator hernia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;167:217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skandalakis LJ, Androulakis J, Colborn GL, Skandalakis JE. Obturator hernia: Embryology, anatomy, and surgical applications. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:71–84. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tschudi J, Wagner M, Klaiber C. Laparoscopic operation of incarcerated obturator hernia with assisted intestinal resection. Chirurg. 1993;64:827–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantoo SK, Mak K, Tan TJ. Obturator hernia: Diagnosis and treatment in the modern era. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:866–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant TL, Umstot RK., Jr Laparoscopic repair of an incarcerated obturator hernia. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:437–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00191635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang SS, Shan YS, Lin YJ, Tai YS, Lin PW. A review of obturator hernia and a proposed algorithm for its diagnosis and treatment. World J Surg. 2005;29:450–4. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7664-1. discussion 454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowbey PK, Bandyopadhyay SK, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M, Wadhwa A, Sharma A. Endoscopic totally extraperitoneal repair for occult bilateral obturator hernias and multiple groin hernias. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14:313–6. doi: 10.1089/lap.2004.14.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cueto-Garcia J, Rodriguez-Diaz M, Elizalde-Di Martino A, Weber-Sanchez A. Incarcerated obturator hernia successfully treated by laparoscopy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:71–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haith LR, Jr, Simeone MR, Reilly KJ, Patton ML, Moss BE, Shotwell BA. Obturator hernia: Laparoscopic diagnosis and repair. JSLS. 1998;2:191–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt L, Morrison C, Lengyel J, Sagar P. Laparoscopic management of an obstructed obturator hernia: Should laparoscopic assessment be the default option? Hernia. 2009;13:313–5. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miki Y, Sumimura J, Hasegawa T, Mizutani S, Yoshioka Y, Sasaki T, et al. A new technique of laparoscopic obturator hernia repair: Report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:652–6. doi: 10.1007/s005950050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno-Egea A, la Calle MC, Torralba-Martinez JA, Morales Cuenca G, Girela Baena E, del Pozo P, et al. Obturator hernia as a cause of chronic pain after inguinal hernioplasty: Elective management using tomography and ambulatory total extraperitoneal laparoscopy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:54–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000202184.34666.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry CP, Hantes JM. Diagnosis and laparoscopic repair of type I obturator hernia in women with chronic neuralgic pain. JSLS. 2005;9:138–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro K, Patel S, Choy C, Chaudry G, Khalil S, Ferzli G. Totally extraperitoneal repair of obturator hernia. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:954–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8212-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorabella RA, Miniati DN, Brandt ML. Laparoscopic obturator hernia repair in an adolescent. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:e39–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun HP, Chao YP. Preoperative diagnosis and successful laparoscopic treatment of incarcerated obturator hernia. Hernia. 2010;14:203–6. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Velasquez-Lopez JG, Gil FG, Jaramillo FE. Laparoscopic repair of obturator bladder hernia: A case report and review of the literature. J Endourol. 2008;22:361–4. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walid MS, Heaton RL. Pararectal and obturator hernias as incidental findings on gynecologic laparoscopy. Hernia. 2010;14:109–11. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu JM, Lin HF, Chen KH, Tseng LM, Huang SH. Laparoscopic preperitoneal mesh repair of incarcerated obturator hernia and contralateral direct inguinal hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16:616–9. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama T, Munakata Y, Ogiwara M, Kawasaki S. Laparoscopic mesh repair of a reducible obturator hernia using an extraperitoneal approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt PH, Bull WJ, Jeffery KM, Martindale RG. Typical versus atypical presentation of obturator hernia. Am Surg. 2001;67:191–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokoyama Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Hori A, Kaneoka Y. Thirty-six cases of obturator hernia: Does computed tomography contribute to postoperative outcome? World J Surg. 1999;23:214–6. doi: 10.1007/pl00013176. discussion 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yip AW, Ah Chong AK, Lam KH. Obturator hernia: A continuing diagnostic challenge. Surgery. 1993;113:266–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deeba S, Purkayastha S, Paraskevas P, Athanasiou T, Darzi A, Zacharakis E. Laparoscopic approach to incarcerated and strangulated inguinal hernias. JSLS. 2009;13:327–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Losanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW. Obturator hernia. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:657–63. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]